Abstract

Fetiform teratoma (homunculus) is a rare but distinct entity, characterized by presence of more organoid differentiation than the classical teratoma but not enough to classify as fetus-in-fetu. Presence of rudimentary limbs in presence/absence of axial skeleton is often reported as an important differentiating feature. Sacrococcygeal location has been reported in a few case reports but in neonates only. This is a rare case of sacrococcygeal fetiform teratoma (Altman type 1) in an 11-year-old girl presenting as a gluteal mass.

Keywords: Fetiform teratoma, Sacrococcygeal teratoma, Gluteal presentation, Altman type 1

Introduction

Sacrococcygeal teratoma (SCT) is a rare tumor with predominant presentation in neonates with a prevalence of 1 in 40,000 births, and female preponderance (4:1) [1]. It arises from the caudal end of spine with different sizes and grades of protrusion [2]. SCT can be categorized as classical, fetiform or homunculus, and malignant. Fetiform teratoma has to be distinguished from fetus-in-fetu [3–5]. Miles reviewed 11 cases of SCT in adults in 20 years, but only one of them had external presentation, and the rest were all intrapelvic presacral masses of classical type only [1]. On the other hand, fetiform teratoma is a distinct entity with highly organized differentiation but without visceral organ differentiation with mainly neonatal presentation. No case of nonneonatal fetiform teratoma was found in literature [3, 4].

Case Report

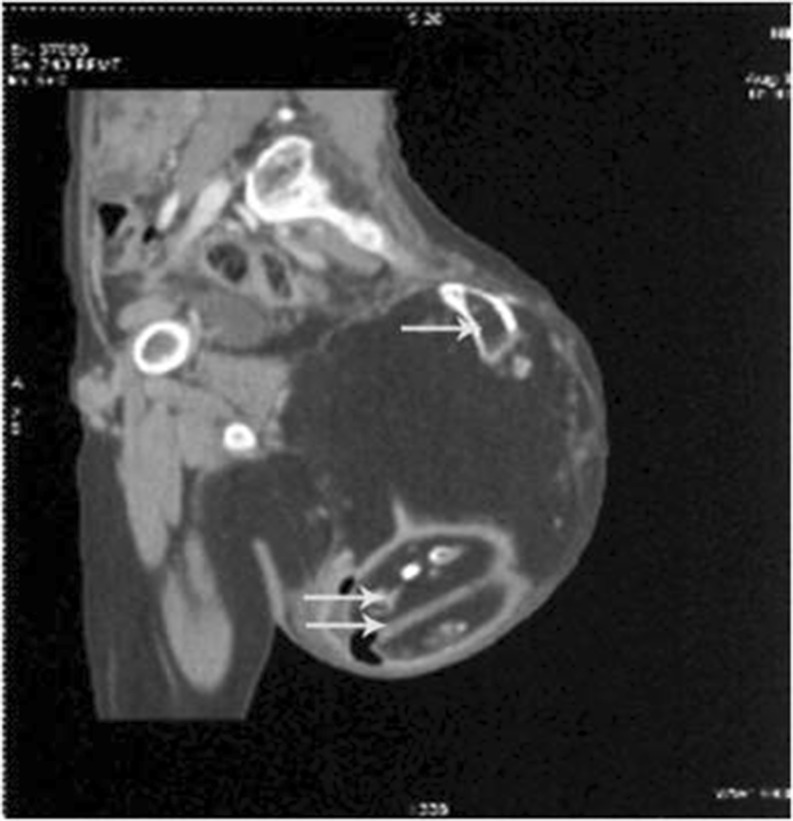

An 11-year-old girl presented with a mass in the left gluteal region, which was noticed at birth and slowly grown to the present size. She limped while walking. The mass was 25 cm in maximum dimension with stretched-out skin on surface. It was nontender, extending just beyond midline, vertically up to the left iliac crest and hanging over the gluteal fold up to the upper third thigh. It was partially fixed to underlying structures. Computed tomographic (CT) scan showed the mass with a variable density pattern along with presence of long bone and foot development with suggestion of fetiform teratoma (Fig. 1). The lesion was excised in toto. Peroperatively, it was mainly in the subcutaneous and submuscular plane under gluteus maximus, attached to the sacrum via fascia only, so the sacrum bone was spared from excision but with removal of coccyx. Two-year follow-up had been uneventful.

Fig. 1.

Lateral view showing mass left gluteal region extending just beyond midline, vertically up to left iliac crest and hanging over gluteal fold up to upper third thigh

On gross examination, a well-circumscribed mass measuring 22 × 15 × 16 cm was discovered, which on bisection showed two rudimentary feet, a long bone resembling femur, solid areas and a large cystic space with smooth and shiny lining, with a tuft of hair (Figs. 2, 3, and 4). Another small cyst filled with pultaceous material was seen embedded in the solid area. A few small tiny nodules were seen protruding within the cavity, whose cut section showed adipose tissue and hair. Multiple cuts did not reveal any axial skeleton or cephalic differentiation. Multiple sections showed differentiation into skin with dermal appendages, hair, adipose tissue, cartilage, bone, lymphoid tissue, neurovascular bundles, and rudimentary toe. No neural tissue including spinal cord, brain matter, or gonadal differentiation was seen. The diagnosis of a highly differentiated teratoma/fetiform teratoma was made.

Fig. 2.

Computed tomographic (CT) scan showing a mass in left presacral region, extending up to iliac crest with a variable density pattern and presence of long bone (arrow) and foot development (double arrow)

Fig. 3.

A well-circumscribed skin covered (arrow) nonencapsulated mass measuring 22 × 15 × 16 cm with a long bone resembling femur (arrowhead)

Fig. 4.

Cut section shows two rudimentary feet (small arrow), a long bone resembling femur (long arrow) and solid areas with a large cystic space with smooth and shiny lining, focally with a tuft of hair (thick arrow). Solid areas show adipose tissue (arrowhead). No cephalic/axial differentiation is noted

Discussion

SCT can be categorized as classical, fetiform or homunculus, and malignant. Fetiform teratomas have to be distinguished from fetus-in-fetu, which is invariably associated with anencephaly and achardia [3–5]. Difference in the origin of the two has been described in the literature [4, 5]. While fetus-in-fetu is a type of twin pregnancy of monozygotic, diamniotic, monochorionic nature and is attributed to unequal division of totipotential cells of the blastocyst with inclusion of these cells into more mature embryo, the fetiform teratoma is a tumor arising from pluripotential cells in Hansen’s node, a primitive knot which is thought to have migrated caudally to coccyx [4, 6]. It may expand anterosuperiorly into abdominoperineal cavity, or into gluteal area posterolaterally, which could possibly be the cause of unusual gluteal presentation as in this case. Derivation of these cells into tissues of one or more than one germinal layer is postulated [2]. Unlike classical SCTs, fetiform teratomas have complex tissue differentiation/organization and organoid differentiation. The caudal development is also seen to be better than cephalic as is also seen in this case lacking any cephalic differentiation. Limb formation is seen more often but visceral organ tissue and skeletal muscle is inconspicuous or absent as is seen in this case [4]. Differentiation into gastrointestinal, genitourinary, external sex organ, respiratory system, and other organs such as thyroid, liver lymph nodes, and spleen has been reported, and in this case only a tiny lymphoid tissue resembling spleen was also identified [4, 7–9]. Kuno et al. have reported highly developed axial skeleton and organ development of brain, eye, trachea, thyroid, blood vessels, gut, and phallus like structure with cavernous structures, but such differentiation was not noted in this case [8]. The presence of axial skeleton has also been variably considered as a distinguishing criterion from classical teratoma, though in this case it was not identified [2, 4, 8]. It has also been proposed that fetiform teratoma can be distinguished from fetus-in-fetu based on zygosity but has not been done in this case [8].

Miles reviewed 11 cases of SCT in adults in 20 years, but only one of them had external presentation, and the rest were all intrapelvic presacral masses, which supports the unusual presentation of this case [1]. Histopathology showed classical dermal derivatives with smooth, striated muscles, cartilage, fat, nerves, and intestinal mucosa in his series, whereas no intestinal differentiation was seen in the present case [1].

Fetiform teratoma has been reported in adults in adnexa and retroperitoneum, unlike this case, while sacrococcygeal location with gluteal presentation as in this case has been reported only in neonates [2, 7, 9, 10]. This patient, from a rural background, had carried this slow-growing gluteal mass for 11 years without any complication and malignant transformation as was also seen in a Nigerian case, but that case report also lacks the histopathological confirmation [11].

Primary treatment for mature SCT consists of complete surgical excision [6]. The coccyx should be routinely removed, not only to expose, but to remove the nidus which may contain totipotent cellular remnants and cause recurrence; and as much of the sacrum as necessary [1]. This case report highlights the rarity with respect to its presentation.

References

- 1.Miles RM, Stewart GS. Sacrococcygeal teratomas in adults. Ann Surg. 1975;179:676–683. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197405000-00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuentes S, Moreno C, Tejedor R, Cabezalí D, Benavent MI, Gómez A (2010) Highly differentiated sacrococcygeal teratoma. Internet J Pediatr Neonatol 12

- 3.Greenberg JA, Clancy TE. Fetiform teratoma (humunculus) Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1:95–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss JR, Burgess JR, Kaplan KJ. Fetiform teratoma (homunculus) Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1552–1556. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1552-FTH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoeffel C, Nguyen K, Phan H, Truong N, Nguyen T, Tran T, et al. Fetus in fetu: a case report and literature review. Pediatrics. 2000;105:1335–1344. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.6.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luk SY, Tsang YP, Chan TS, Lee TF, Leung KC. Sacrococcygeal teratoma in adults: case report and literature review. Hong Kong Med J. 2011;17:417–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbott TM, Hermann WJ, Scully RE. Ovarian fetiform teratoma (homunculus) in a 9-year-old girl. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1984;2:392–402. doi: 10.1097/00004347-198404000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuno N, Kadomatsu K, Nakamura M, Miwa-Fakuchi T, Hirabayashi N, Ishizuka T. Mature ovarian cystic teratoma with a highly differentiated homunculus: a case report. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70:40–46. doi: 10.1002/bdra.10133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyake J, Ireland K. Ovarian mature teratoma with homunculus coexisting with an intrauterine pregnancy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:1192–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venkatachala S, Shanthakumari S. Retroperitoneal fetiform teratoma. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:581–582. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.68251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozoilo KN, Yilkudi MG, Ede JA. Sacrococcygeal teratoma in an adult female Nigerian. Ann Afr Med. 2008;7:149–150. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.55661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]