Abstract

Laparoscopic surgery has come to replace many conventional abdominal surgeries because of its outstanding advantages, including a better cosmetic result, faster recovery, and lesser postoperative pain. We present a case of laparoscopic-assisted total excision of Todani type I(B) choledochal cyst and biliary reconstruction in a 24-year-old female patient. Dissection of the cyst was done laparoscopically using the monopolar diathermy energy source. An end-to-side hepaticojejunostomy was created intracorporeally using 3–0 Vicryl suture, and end-to-side enteroenterostomy was completed outside the abdominal cavity using the E.K. glove port as wound protector. A new pair of gloves was then used to construct the glove port that served as the optical port. Additional instruments for retraction and suturing were deployed through the port whenever necessary. The use of the glove port also eliminated the need to suture the umbilical port before the completion of surgery. No intraoperative complications or technical problems were encountered using this technique. The use of the E.K. glove port makes it more a convenient and cost-effective procedure in a country like India.

Keywords: Choledochal cyst, E.K. port, Glove port, Laparoscopic hepaticojejunostomy, Extracorporeal jejunojejunostomy, Intracorporeal suturing, Innovative, Cystolithiasis

Background

Choledochal cysts are cystic transformations of the biliary tree. It is a rare entity in western countries but has a higher rate of occurrence in Asia [1]. This disorder is usually diagnosed during childhood and is more common in females [1]. Choledochal cysts are usually diagnosed in childhood, and only about 25 % are detected in adult life [2]. The most commonly used classification of choledochal cyst is the Todani modification of the Alonso-Lej classification, the most common type being type I consisting of cystic, focal, and fusiform dilatation [3]. Complete cyst excision and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy have become a standard procedure in open surgery for choledochal cyst for many years. With the development of laparoscopic experiences and techniques, this complex procedure has also been attempted laparoscopically [4, 5, 7–9].

Herein, we present a case of laparoscopic-assisted correction of a choledochal cyst, discuss the technical aspects, and describe the role of E.K. glove port [6] as a wound protector and the optical port.

Case Presentation

A 24-year-old female patient presented with recurrent mild upper abdominal pain with dyspepsia. She had no palpable mass in the abdomen nor did she have jaundice. Her blood laboratory examinations were within normal limits. Ultrasonography demonstrated large dilatation of the common bile duct (CBD) with choledocholithiasis. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a type I(B) choledochal cyst with cystolithiasis (Fig. 1). The patient underwent laparoscopic excision of the choledochal cyst, hepaticojejunostomy, and extracorporeal jejunojejunostomy of the Roux-en-Y limb using the E.K. glove port as the wound protector.

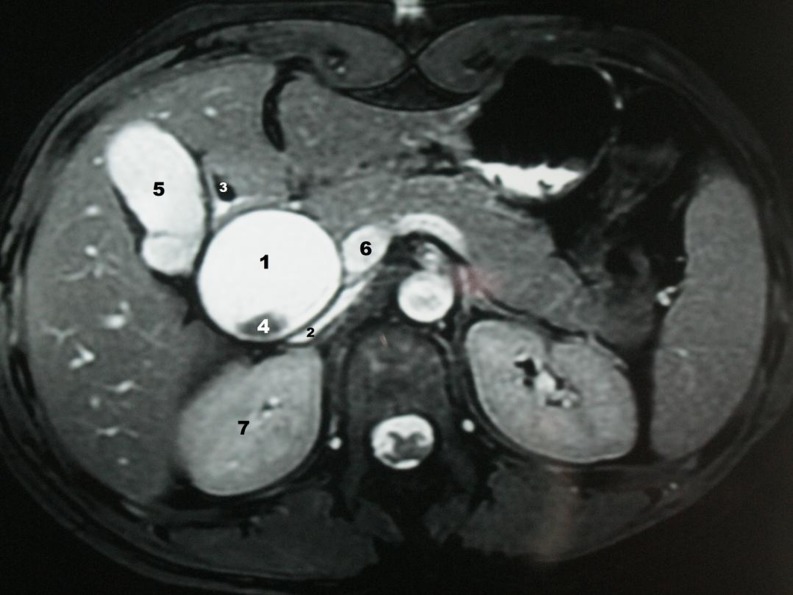

Fig. 1.

T 2-weighted axial MRI showing large cystic dilatation of the CBD (1) which is compressing the inferior vena cava posteromedially (2) and displacing the duodenum anteriorly (3). Hypointense calculus (4) is noted within the cystic lesion. Also seen are the gallbladder (5), portal vein (6), and the upper pole of the right kidney (7)

Operative Techniques

The patient was placed in supine position on the operating table and underwent general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. A preoperative dose of cephalosporin was administered after negative skin test. The abdomen was prepared with Savlon, Betadine, and spirit and was draped with sterile linen. The surgeon stood on the patient’s left side, and the assistant was on the surgeon’s left side. The scrub nurse stood on the patient’s right side. A 10-mm transumbilical, vertical skin incision was made. A 10-mm 30° laparoscope was introduced through the port, and CO2 pneumoperitoneum was induced through it and maintained at 12–14 mmHg. This transumbilical incision was later increased to 3 cm for the introduction of the E.K. glove port that served as a wound protector for the extracorporeal jejunojejunostomy. The patient was then put in reverse Trendelenburg position and tilted slightly left laterally for the remainder of the procedure. A 10-mm trocar in the epigastrium and two 5-mm trocars on the right side of the abdomen were placed under vision. The fundus of the gallbladder was held with a grasper inserted through the right 5-mm lateral port and retracted over the liver toward the right shoulder to expose the Calot’s triangle. The cystic artery was identified, dissected, clipped, and divided. The choledochal cyst was identified (Fig. 2), and dissection of the cyst started from its anterosuperior surface and continued distally to the transition area of the cyst at the head of the pancreas. The cyst was carefully separated from the hepatic artery and portal vein using a monopolar electrocautery device to ensure hemostasis of the epicholedochal venous plexus. Once the portal vein and hepatic arteries were separated from the cyst, the dissection was carried inferiorly toward the pancreas. The cyst was eventually found to taper rapidly to a small duct. The CBD was then ligated using 1–0 silk suture and reinforced or clipped with a metallic clip distally, and two clips were applied proximally to avoid contamination of the peritoneal cavity with the cyst content. The cyst was divided using a pair of scissors. The transected cyst was then dissected cephalad until the normal caliber common hepatic duct (CHD) was identified. At this juncture, cholecystectomy was performed, but the CHD was not divided to minimize peritoneal spillage with bile. Markings were made in the jejunum with 3–0 Vicryl suture at 25 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz for the Roux-en-Y limb and at 45 cm from the first marking for the jejunojejunostomy.

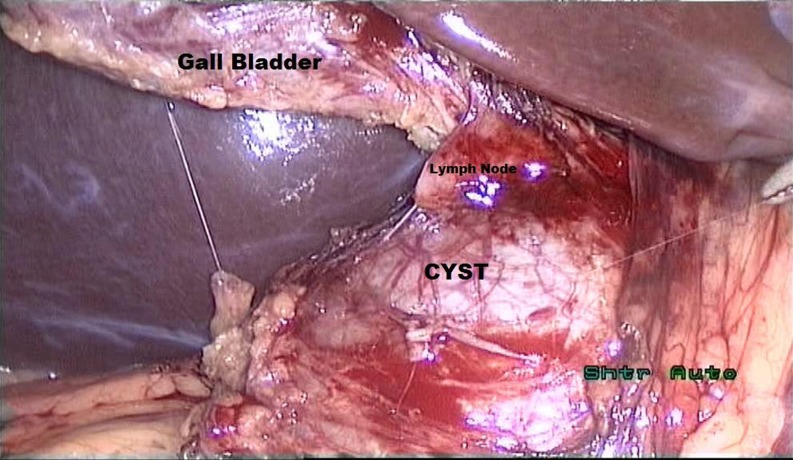

Fig. 2.

Photograph showing intact choledochal cyst with its relations

The E.K. glove port was next constructed, which served as a wound protector before the intestine was brought out of the abdomen. The materials required to make the E.K. glove port are as follows (Fig. 3):

A flexible rubber inner ring (diameter 5–6 cm)

A plastic rigid outer ring (diameter 11–12 cm)

A pair of surgical gloves

Standard laparoscopic trocars

Fig. 3.

Materials required for making the E.K. glove port

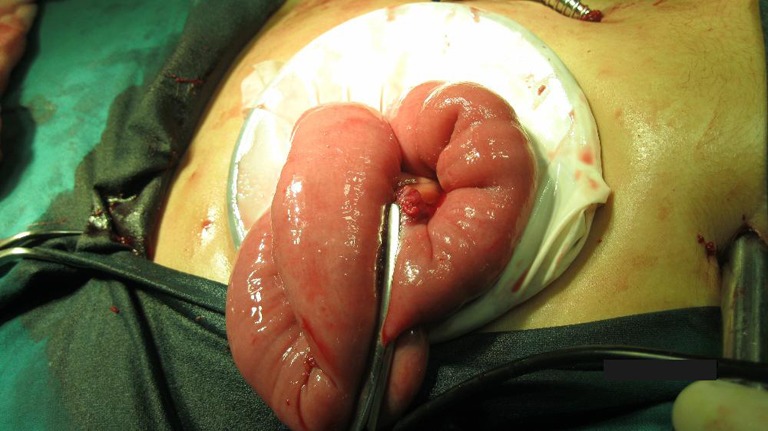

The open end of the glove was passed through the flexible inner ring (Fig. 4) and turned over the ring so that the flexible ring was in between the two layers of the glove (Fig. 5). The umbilical port was then extended to 3 cm, and the inner flexible ring, fitted with the glove, was then introduced into the abdomen assisted by a retractor and fingers (Fig. 6). The outer rigid ring was placed over the glove, and the open end of the glove was then wrapped around the outer rigid ring (Fig. 7). The fingers of the glove was transacted at the base (Fig. 8) and wrapped around the outer rigid ring to form the “wound protector” (Fig. 9). The jejunum was then exteriorized through our modified wound protector and transected at the previously marked sites for the Roux-en-Y limb (Fig. 10). End-to-side jejunojejunostomy was performed with continuous Lambert sutures and interrupted seromuscular sutures at the previously marked site.

Fig. 4.

Open end of the glove passed through the inner flexible ring

Fig. 5.

Flexible ring in between the two layers of the glove

Fig. 6.

Inner flexible ring along with the glove being introduced into the abdomen

Fig. 7.

Open end of the glove wrapped around the outer rigid ring

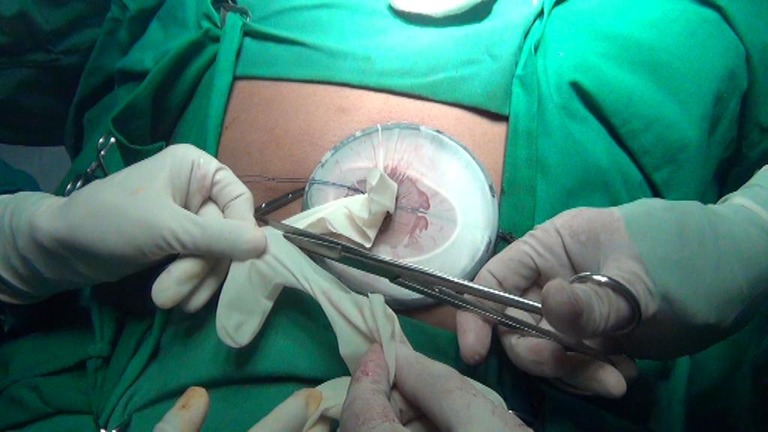

Fig. 8.

Fingers of the glove transected at the base

Fig. 9.

Transected part of the glove wrapped over the outer rigid ring to form the “wound protector”

Fig. 10.

Intestine exteriorized through the E.K. port for jejunojejunostomy

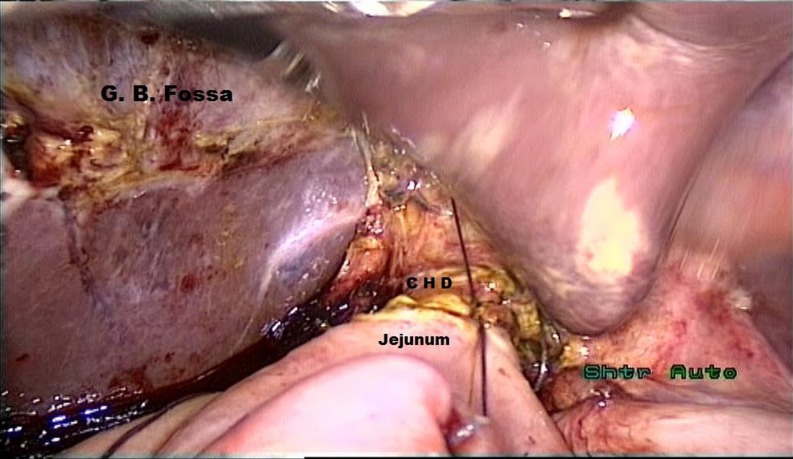

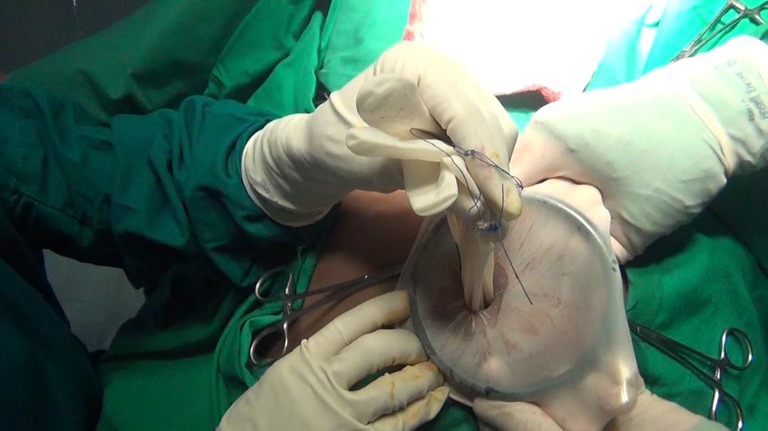

Bowel was repositioned into the peritoneal cavity, and a new pair of glove was used to make the E.K. glove port that served as the optical port (Fig. 11). The glove port also served as the port of entry for a variety of instruments for retraction and suturing. On introduction of the telescope, the jejunojejunostomy site was rechecked and confirmed to be in good position without any evidence of torsion or bleeding. A window was created in the transverse mesocolon, and the Roux limb was brought retrocolic to the porta hepatis for hepaticojejunostomy. The CHD was transected, and the cyst along with the gallbladder was introduced into a retrieval bag and placed in the subdiaphragmatic space. The jejunum was opened with the help of a monopolar hook cautery on the antimesenteric border and a single-layer end-to-side hepaticojejunal anastomosis was fashioned using 3–0 Vicryl interrupted sutures (Fig. 12). After it was ensured that there was no bleeding, a drain was placed near the anastomotic site, and the specimen was extracted through the E.K. glove port in the umbilicus (Fig. 13). The umbilical wound was repaired with 1–0 PDS suture, and the skin was approximated with 3–0 Vicryl Rapide.

Fig. 11.

A new pair of gloves is used to construct the E.K. port for the telescope

Fig. 12.

Anterior layer of the end-to-side hepaticojejunostomy

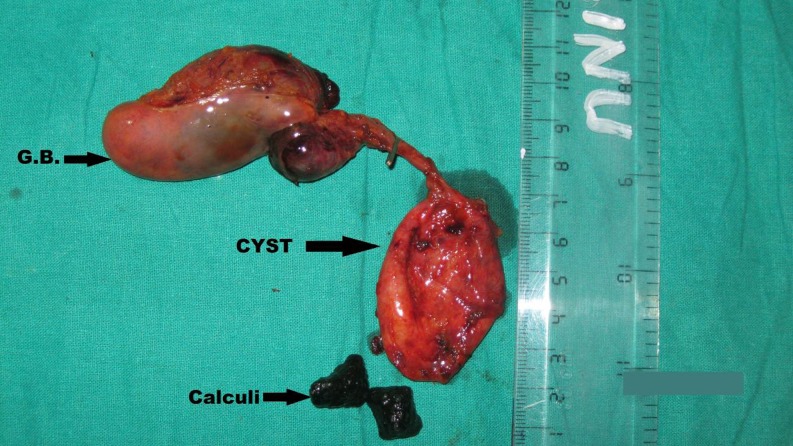

Fig. 13.

Specimen after extraction

Postoperative Course

Total operation time was 300 min. Although the operation went excellently without any intraoperative complication or technical problem, the patient developed fever with pain in the abdomen on the fifth postoperative day. Computed tomography scan revealed pelvic collection, but no collection was evident in the subhepatic region. The pelvic collection was drained percutaneously, and a 7-Fr silicone pigtail tube was placed. About 250 mL of blood stained with yellowish-colored fluid was aspirated. Retrospectively, we assume this fluid to be the irrigation fluid that we used during the dissection of the cyst, which we failed to aspirate. On the hindsight, we realized that a pelvic drain was also essential, if not mandatory, for drainage of gravitated irrigation fluid. The patient was able to start oral diet on the eighth postoperative day. The drains were removed on the 10th postoperative day, and the patient was discharged on the 12th postoperative day.

Discussion

Laparoscopic choledochal cyst resection and Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomy were first described by Farello et al. in 1995 in a 6-year-old girl [7]. Since then, several authors have reportedly used this technique for surgical resection of choledochal cysts [1, 2, 4, 5, 7–9]. The advantages of laparoscopy include magnification of intracorporeal structures, greater accuracy, and improved immediate postoperative recovery [4, 5]. In addition, a long subcostal incision is avoided, allowing less pain and excellent cosmetic effect (Fig. 14). Nevertheless, because of the complex hepatojejunostomy and a prolonged pneumoperitoneum, the laparoscopic approach may potentially be a technical challenge in the treatment of patients with choledochal cyst [4]. In the case presented herein, the choledochal cyst was easily, precisely, and safely dissected from the portal vein and hepatic artery. In addition, the surgeon was able to reproduce the same procedures of hepaticojejunostomy as are performed in conventional open laparotomy. The proper technique of Roux-en-Y anastomosis has been a matter of debate. Some authors suggested intracorporeal anastomosis, using an endo-GIA [8, 9], whereas others favored anastomosis extracorporeally via a small extension of the umbilical port [1, 5]. We extended the umbilical incision to 3 cm and introduced the E.K. glove port that acted as the wound protector. The jejunum was then exteriorized easily, and anastomosis was performed extracorporeally. The pause of carbon dioxide insufflation at this time might potentially improve the ventilation and hemodynamic status intraoperatively [4]. After the bowel was repositioned into the peritoneal cavity, a new pair of glove was used to make the E.K. glove port that served as the optical port. The glove port also served as the port of entry for a variety of instruments for retraction and suturing. One more added advantage of this glove port is that we do not have to close the incision before the completion of the surgery and it also eliminated the trouble of gas leakage.

Fig. 14.

Postoperative scar, day 14

Conclusion

Laparoscopic excision of choledochal cysts, although technically challenging, is safe and feasible in experienced hands. The outcome appears superior to that of open surgery. The laparoscopic approach has the potential to replace the conventional approach in the near future as the standard procedure of surgical treatment. The use of the E.K. glove port makes it more a convenient and cost-effective procedure in a country like India.

References

- 1.Akaraviputh T, et al. Robot-assisted complete excision of choledochal cyst type I, hepaticojejunostomy and extracorporeal Roux-en-Y anastomosis: a case report and review literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:87. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-8-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, Lam CM, Poon RT, Wong J. Choledochal cysts in adults. Arch Surg. 2002;137:465–468. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Congenital bile duct cysts: classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977;134:263–269. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(77)90359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liuming H, Hongwu Z, Gang L, et al. The effect of laparoscopic excision vs open excision in children with choledochal cyst: a midterm follow-up study. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:662–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen Thanh L, Hien PD, le Dung A, Son TN. Laparoscopic repair for choledochal cyst: lessons learned from 190 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:540–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khiangte E, Newme I, Phukan P, Medhi S. Improvised transumbilical glove port: a cost-effective method for single port laparoscopic surgery. Indian J Surg. 2011;73(2):142–145. doi: 10.1007/s12262-010-0215-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farello GA, Cerofolini A, Rebonato M, et al. Congenital choledochal cyst: video-guided laparoscopic treatment. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1995;5:354–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn SM, Jun JY, Lee WJ, et al. Laparoscopic total intracorporeal correction of choledochal cyst in pediatric population. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:683–686. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gander JW, Cowles RA, Gross ER, et al. Laparoscopic excision of choledochal cysts with total intracorporeal reconstruction. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20(10):877–881. doi: 10.1089/lap.2010.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]