Abstract

Gastric teratoma is a rare tumor, accounting for less than 1 % of all teratomas in infants & children. To date, only about 102 cases have been reported in the literature. A 10 month old infant was brought with a history of upper abdominal mass which was otherwise asymptomatic. On evaluation it was diagnosed as gastric teratoma. On laparotomy the mass was found to be originating from lesser curvature of stomach. Mass was excised and histopathologically it was a mature cystic teratoma. No recurrence after 18 months of follow-up.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12262-012-0568-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Gastric, Teratoma, Stomach, Teratomas, Germ cell tumors

Introduction

Teratomas are embryonic neoplasms which arise from totipotent cells and contain elements from all three germ layers (i.e., ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm) and may be benign or malignant. They commonly arise in the ovary and testis.

Gastric teratoma is a rare tumor, accounting for less than 1 % of all teratomas in infants and children [1, 2]. Gastric teratomas are however the most common teratomas of the gastrointestinal tract. The other common sites are oropharynx and tongue [2]. To date, only about 102 cases of gastric teratomas have been reported in the world literature [3]. Hence, we report this rare case of gastric teratoma in an infant.

Case Report

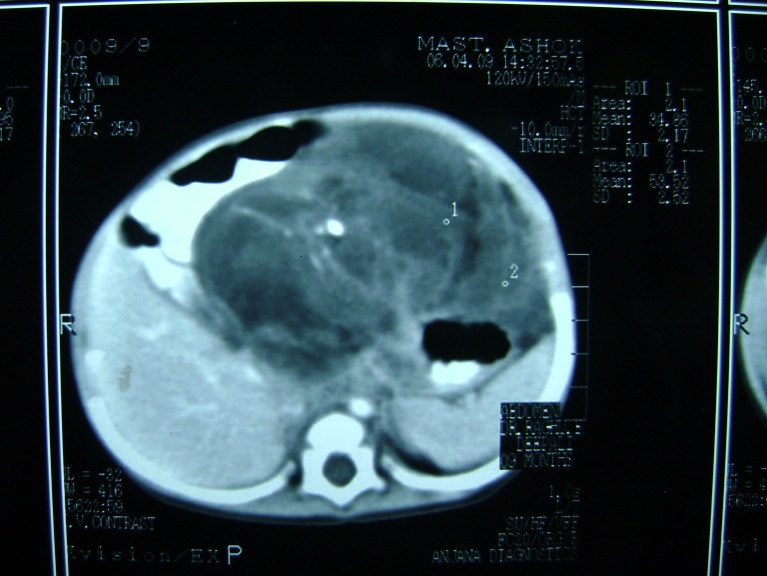

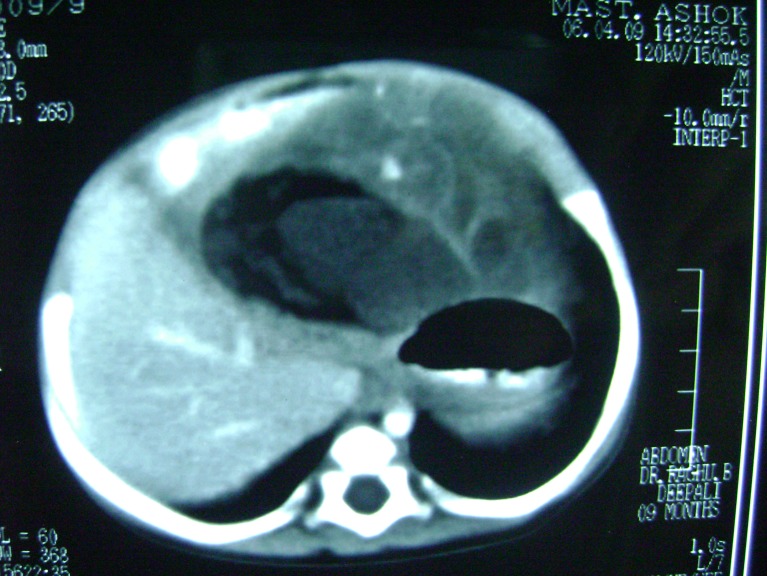

A 10-month old infant presented with an abdominal mass of 1-month duration. Abdominal examination revealed a mass of size 8 × 12 cm occupying epigastric and left hypochondriac regions, smooth surface, firm in consistency, freely mobile and all borders of the mass could be well made out. Hematological examination showed hemoglobin to be 8.8 g%. Alpha Fetoprotein (AFP) 7.15 ng/ml (normal 0.2–9.0 ng/ml) and beta-HCG <2.0 mIU/ml (normal <4 mIU/ml) were within normal limits. The plain abdominal X-ray report was normal. On ultrasound, a mass consisting of solid and cystic spaces, occupying the upper abdomen of size 173 × 76 mm, was noticed, and contrast-enhanced CT was reported as a mixed density mass with solid and cystic components, areas of fat, calcification and soft tissue attenuation in the epigastric region attached to the stomach, suggestive of gastric teratoma (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

CT scan of teratoma. Calcifications & fat attenuation seen

Fig. 2.

CT scan showing the solid & cystic components of tumor

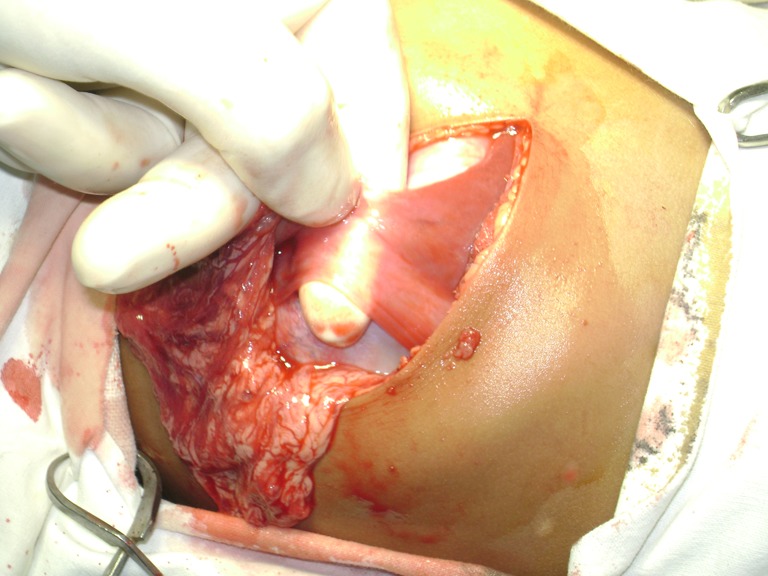

With the preoperative diagnosis of gastric teratoma, the child was posted for laparotomy and abdomen entered through left subcostal incision. On laparotomy the mass was found to be originating from the lesser curvature of the stomach and also attached to the falciform ligament of the liver through a fibrous band (Figs. 3 and 4 and Online resource 1). The mass was mobilized and excised with a rim of the gastric wall at its attachment to the lesser curvature (Fig. 5). No enlarged lymph nodes were noted. The stomach wall was closed in two layers. Postoperative period was uneventful.

Fig. 3.

Fibrous band like attachment to falciform ligament

Fig. 4.

Teratoma attached to lesser curvature of stomach

Fig. 5.

Specimen

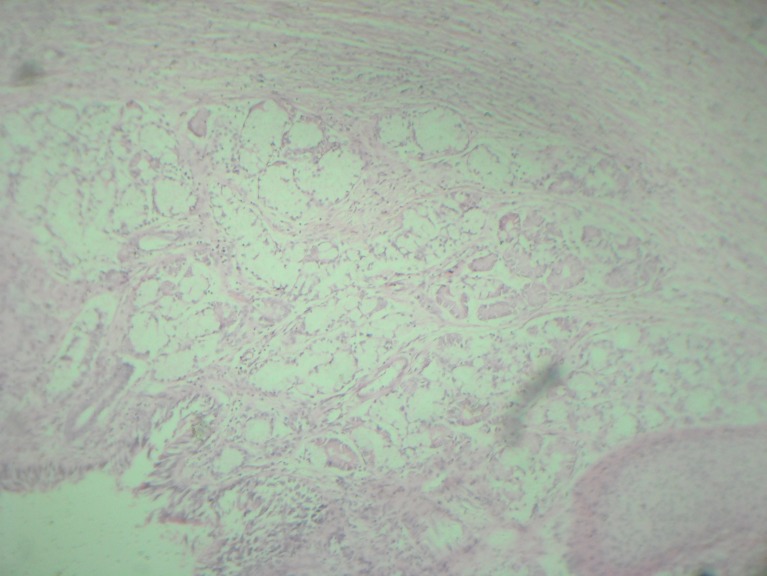

Histopathological examination was reported as mature cystic teratoma of extragonadal origin (Figs. 6 and 7). The child had been followed up at regular intervals for past 18 months by clinical and ultrasound examination. There was no evidence of tumor recurrence.

Fig. 6.

Section shows respiratory epithelium & chondroid area

Fig. 7.

HPE-intestinal epithelium, adnexal glands & musculature

Discussion

Gastric teratomas most commonly present with an abdominal mass. Teratomas with intramural extension have also been reported as presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding or respiratory distress [3]. Other associated findings have been premature labor and dystocia [4]. Most of the reported cases are in males, but they can occur in females with a lesser frequency [2, 3, 5]. Teratomas can be classified into three types according to their histologic composition. Mature teratomas consist of well-differentiated tissue; immature teratomas have varying degrees of immature fetal tissues and the malignant type contains at least one of the malignant germ cell elements [6]. Immature teratomas are also graded (from 1 to 3) by the amount of immature tissue contents, which are mainly neural elements, and by the degree of mitotic activity [7].

Diagnosis of gastric teratoma might be feasible by detecting the presence of calcification on abdominal radiographs and more accurately on abdominal CT [8, 9]. Most mature cystic teratomas can be diagnosed with ultrasound. In a prospective study by Mais et al. [10], it has been found that endo-ultrasound had a sensitivity of 58 % and a specificity of 99 % in the diagnosis of mature cystic teratomas. Numerous pitfalls have been described in the ultrasound diagnosis of mature cystic teratomas [11]. On CT, the well-defined mass with separate cystic and solid components in varying proportions, fat attenuation within a cyst, with or without calcification in the wall, and coarse globular calcifications within solid components is diagnostic for mature cystic teratomas [8, 9]. The presence of solid, cystic, and calcified tissues in the left suprarenal location suggests two diagnoses: neuroblastoma and gastric teratoma. The intragastric location of the mass increases the likelihood that the mass is a gastric teratoma, whereas the mass arising from the adrenal is suggestive of neuroblastoma [9]. In our case the diagnosis of the gastric teratoma was established after performing CT scan.

AFP synthesis occurs in the fetal liver, yolk sac, and gastrointestinal tract. Preoperatively, an abnormally-elevated level can be obtained because of the presence of the intestine in these teratomas or due to the presence of germ cell tumors in immature teratomas. Therefore, a serum AFP level is very useful as it provides information regarding recurrence or presence of residual tumors and malignant transformation [3, 4, 12].

Grossly, gastric teratomas have both cystic and solid components. The tumor is commonly exogastric. The commonest site of origin is the posterior wall of the stomach, followed by the lesser curvature and the anterior wall of the stomach [2, 3].

Treatment for mature gastric teratoma is surgical removal. Complete surgical excision is curative. Total excision and primary closure of the gastric wall is the treatment of choice [2, 3, 12, 13]. Partial, subtotal, and total gastrectomies have been performed as dictated by the extent of stomach involvement [5]. In a series of cases, Gupta et al. [3] have reported a case of immature teratoma in a 6-month-old infant arising from lesser curvature of the stomach extending into the left lobe of the liver and transverse colon. The tumor was resected along with left hepatic lobectomy and resection and end-to-end anastomosis of the transverse colon and the child being asymptomatic after 18 months of follow-up. The prognosis following surgical excision of a mature gastric teratoma has been shown to be excellent [2, 3, 5]. No cases of recurrence in mature teratomas after primary surgical excision have been reported so far, except for Gupta et al. [13] reporting a case of mature gastric teratoma developing recurrence after two decades of complete surgical excision, prompting regular follow-up after surgical treatment. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are not recommended [3].

Electronic supplementary material

Video showing laparotomy and exploration. (AVI 10029 kb)

References

- 1.Cairo MS, Grosfeld JL, Weetman RM. Gastric teratoma: unusual cause for bleeding of the upper gastrointestinal tract in the newborn. Pediatrics. 1981;67:721–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herman TE, Siegel MJ. Congenital gastric teratoma. J Perinatol. 2008;28(11):786–787. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta DK, Srinvas M, Dave S, et al. Gastric teratoma in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2000;16:329–332. doi: 10.1007/s003830000390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matias IC, Huang YC. Gastric teratoma in infancy: a report of a case and review of world literature. Ann Surg. 1973;178:631–636. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197311000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gamangatti S, Kandpal H. Gastric teratoma. Singap Med J. 2007;48(4):e99–e101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cushing B, Perlman EJ, Marina NM, Castleberry RP. Germ cell tumors. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and practice of pediatric oncology. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. pp. 1091–1113. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakhlu A, Wakhlu AK. Pediatric gastric teratoma. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2002;12:375–378. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-36851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowen B, Ros PR, McCarthy MJ, Olmsted WW, Hjermstad BM. Gastrointestinal teratomas: CT and US appearance with pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1987;162:431–433. doi: 10.1148/radiology.162.2.3541031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Outwater EK, Siegelman ES, Hunt JL. Ovarian teratomas: tumor types and imaging characteristics. RadioGraphics. 2001;21:475–490. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.2.g01mr09475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mais V, Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Angiolucci M, Paoletti AM, Melis GB. Transvaginal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of cystic teratoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:48–52. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00323-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hertzberg BS, Kliewer MA. Sonography of benign cystic teratoma of the ovary: pitfalls in diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:1127–1133. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.5.8911163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ratan KN, Mathur SK, Marwah N, Purwar P, Rohilla S, Balasubramaniam G. Gastric teratoma. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71(2):171–172. doi: 10.1007/BF02723103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta V, Babu RY, Rana S, Vaiphei K, Rao KL, Bhasin DK. Mature gastric teratoma: recurrence in adulthood. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(2):e17–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.10.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video showing laparotomy and exploration. (AVI 10029 kb)