Abstract

Background

Primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL) is a very rare malignancy, and constitutes about 0.016 % of all cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and is often misdiagnosed. The optimal therapy is still unclear and the outcomes are uncertain. Among PHLs, a primary hepatic low-grade marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) is extremely rare.

Methods

We present a case of primary hepatic lymphoma (MALT lymphoma) treated with surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy. A 38-year-old Korean man, who was diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B 20 years ago, was admitted for liver biopsy after liver lesions were detected on follow-up computed tomography scan (CT). Liver biopsy revealed the diagnosis of marginal zone B-cell malignant lymphoma (MALT lymphoma). The preoperative clinical staging was IE, given that no additional foci of lymphoma were found anywhere else in the body. The patient underwent left hemihepatectomy. Subsequently, the patient received two cycles of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisone) regimen.

Results

After 15 months of follow-up, the patient is alive and well without any evidence of disease recurrence.

Conclusion

Although the prognosis is variable, good response to early surgery combined with postoperative chemotherapy can be achieved in strictly selected patients.

Keywords: Primary hepatic lymphoma, MALT lymphoma, Chronic hepatitis B, Surgery, Adjuvant chemotherapy

Introduction

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) is a common lymphoproliferative disease; liver involvement occurs in 10 % of patients and defines advanced disease [1]. In contrast, primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL) is a very rare malignancy, and constitutes about 0.016 % of all cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and is often difficult to be correctly diagnosed [2]. It usually presents with constitutional symptoms, hepatomegaly and signs of cholestatic jaundice, and rarely acute hepatic failure [3]. Among PHLs, a primary hepatic low-grade marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) is extremely rare. Although the liver contains lymphoid tissue, host factors may make the liver a poor environment for the development of malignant lymphoma [4]. Even though there have been reports regarding this disease entity, wherein most patients were treated with chemotherapy, with some physicians employing a multimodality approach including surgical resection, the optimal therapy is still unclear and the outcomes are uncertain [2, 5–7]. We present a case of hepatic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma treated with surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy.

Case Presentation

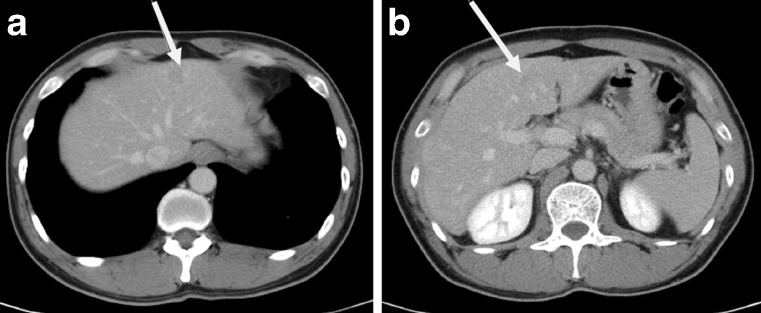

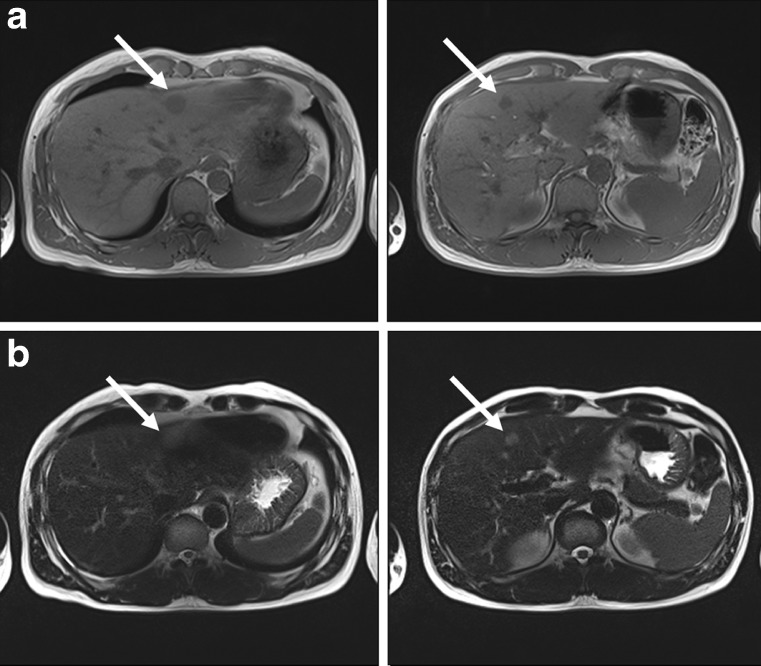

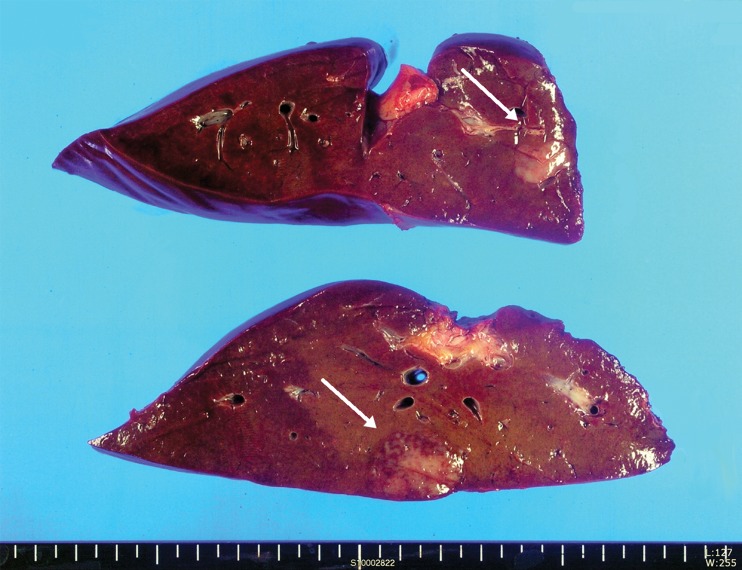

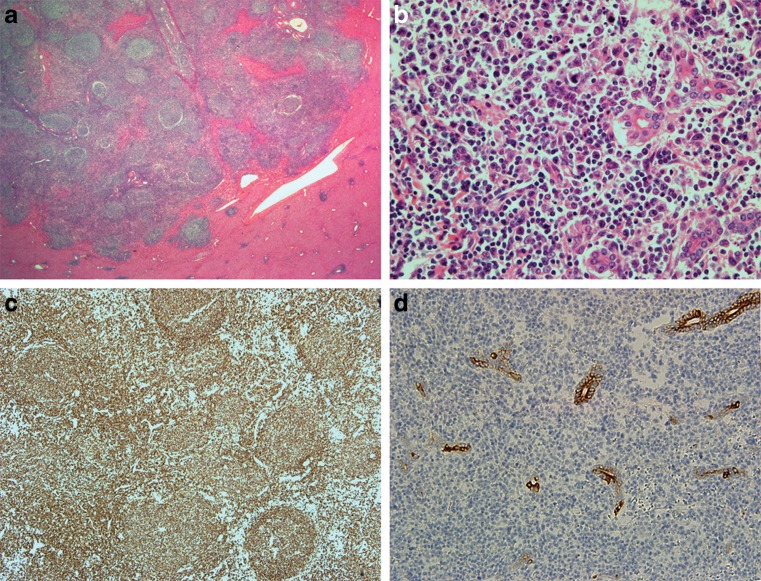

A 38-year-old Korean man, who was diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B 20 years ago, visited our hospital for regular checkups. The patient denied any fever, night sweats, vomiting, chest pain, diarrhea, jaundice, blood in stool, or weight loss. His family history was significant and both his parents had been diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma. The physical examination revealed no palpable mass, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or any peripheral stigmata of chronic liver disease. Laboratory results included hemoglobin 13.3 g/dl and a white cell count of 6.7 × 109/l, with a normal differential count. Alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were within their normal limits. The serum beta-2 microglobulin and ferritin levels were within normal ranges. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen and alpha-fetoprotein levels were also within normal ranges. Serologic test for hepatitis B virus (HBV) was positive, and the serum HBV-DNA level detected by polymerase chain reaction was 562,000 IU/ml. Serologic tests for the hepatitis C virus (HCV), Epstein–Barr virus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were negative. Serum calcium was within normal limits. Immunoglobulin levels were normal without any monoclonal peak in the blood or urine. The patient was admitted for further evaluation. CT scan showed low attenuation lesions which were 1.5 and 1.0 cm in size and located in the left lateral and medial section, respectively. The rest of the liver parenchyma was normal without any findings of cirrhosis or ascites. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy and the spleen was normal in size (Fig. 1). The MRI scan (using Primovist for contrast enhancement) also revealed two mass lesions, which demonstrated low-signal intensity on T1-weighted image and subtle high-signal intensity on T2-weighted image which indicated the presence of a malignant tumor such as metastatic tumor or lymphoma (Fig. 2). After admission, the patient underwent ultrasound-guided liver biopsy aiming the lesion in segment 4. There were no immediate postprocedure complications. Marginal zone B-cell lymphoma was diagnosed on liver biopsy. 18 F-FDG positron emission tomography (F-18 FDG PET) scan was also performed. It showed a nodular moderate hypermetabolic lesion in the left lateral part and a small mild hypermetabolic lesion in segment 4 which is suggestive of malignant lesions. There were no other abnormal hypermetabolic lesions on the F-18 FDG PET scan. CT scans of the neck and chest revealed no evidence of mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy or any other abnormal lymphadenopathy. The bone marrow biopsy and aspirate showed no evidence of lymphoma involvement. The patient was diagnosed with primary marginal zone B-cell malignant lymphoma stage IE of the liver, given that no additional foci of lymphoma were found anywhere else in the body, and was referred to the surgical department. He underwent left hemihepatectomy. On exploration, there was minimal lymph node enlargement without hepatomegaly or splenomegaly. There was no evidence of liver cirrhosis. Although the lesion in segment 4 was close to the middle hepatic vein, there were no adhesions or invasions to the adjacent organs. The lymph nodes along the common hepatic artery (8a) and adjacent to the gallbladder were enlarged and were dissected. After cholecystectomy and individual hilar structure dissection (left hepatic artery and left portal vein) for left hemihepatectomy, parenchymal transection was performed by the clamp-crushing method using Kelly forceps. There were no immediate postoperative complications and the patient was discharged on the ninth postoperative day. Gross findings of the resected liver are shown in Fig. 3. The findings of the initial biopsy and resected liver specimen showed marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MALT lymphoma), and regional lymph nodes showed reactive hyperplasia without lymphoma involvement. The two hepatic lesions were basically identical histologically; relatively circumscribed, but showed infiltration into the liver parenchyma and bile ductules with lymphoepithelial lesions, and showed heavy infiltration of small lymphocytes, plasma cells, centrocyte-like cells, and some blasts with numerous reactive follicles. Interfollicular cells were positive for CD20 and IgM with minor components of VS38-positive cells, lambda-monoclonal plasma cells, and IgD-positive cells. The germinal centers were negative for bcl-2. CD3- and CD5-positive T cells were seen around the B-cell lesions. The immunohistochemical staining against hepatocyte antigen, CK7, and CK19 showed invasion of lymphoid cells, resulting in lymphoepithelial lesions (Fig. 4). Ki-67 labeling index in neoplastic cells was about 20 %.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative CT findings of the PHL patient. White arrows indicate low attenuating lesions located in the a left lateral section (1.5 cm) and b medial section (1.0 cm)

Fig. 2.

Preoperative MRI findings of the PHL patient. a Low signal intensity lesions demonstrated on T1-weighted image and b subtle high-signal intensity on T2-weighted images which indicated the presence of a malignant tumor such as lymphoma or metastatic tumor

Fig. 3.

Gross findings of the resected liver. The cut surface shows two poorly defined, red-gray, solid, firm masses, measuring 2.5 cm × 1.5 cm and 1.5 cm × 1 cm on cross section, respectively. The remaining cut surface does not demonstrate cirrhotic appearance

Fig. 4.

Histologic findings of the liver. The lymphoid infiltration is relatively circumscribed, but is infiltrative into the surrounding liver and bile ductules. Numerous reactive lymphoid follicles are seen (a). The small lymphocytes, plasma cells, blasts, and centrocyte-like cells infiltrating bile ductules are seen (b). Most of the cells are positive for CD20 (c). The CK19-positive ductules show infiltration of lymphoid cells (lymphoepithelial lesions) (d)

After discharge, he was readmitted to our oncology department for chemotherapy. To date, the patient has received two cycles of the CHOP (cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisone) regimen. After 15 months of follow-up, he is alive and well without any evidence of disease recurrence.

Discussion

Primary hepatic lymphoma is defined as lymphoma either confined to the liver or having major liver involvement [1]. PHL is notably rare, representing <1 % of all extranodal lymphomas [8, 9]. The majority (67 %) of PHL patients are middle-aged men (median age 50 years) who usually present with abdominal pain, nausea, and constitutional symptoms [1, 8]. Hepatomegaly is found in most patients (75–100 %); B symptoms such as fever, drenching sweats, and weight loss are present in 37–86 % and jaundice in 4 % [1, 6] of the patients. PHL may present as a solitary mass (42 %) or as multiple lesions (50 %); diffuse infiltration of the liver is more common in Chinese patients and is rare in Caucasians with PHL (8 %). Based on liver infiltration, PHL can be subdivided into nodular or diffuse types [10]. The pattern of liver infiltration has no prognostic value [1, 11]. Similarly, the disease may be of either T- or B-cell origin [10]. Most PHL corresponds to a larger cell type and demonstrates a B-cell immunophenotype [5]. The predominant histological type of PHL is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [6, 8]. Other histologic subtypes of PHL include high-grade tumors (lymphoblastic and Burkitt lymphoma, 17 %), follicular lymphoma (4 %), diffuse histiocytic lymphoma (5 %), marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MALT lymphoma), anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, and T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma [6]. Primary hepatic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type (MALT lymphoma) is a rare entity with only 48 cases being reported in the worldwide literature since the first report by Isaacson et al., which accounts for 1.6–3 % of PHL [12, 13].

Patients with PHL usually have elevated liver function tests, mostly LDH and alkaline phosphatase [6, 14]. Elevated LDH, with normal alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and CEA, remains a valuable biologic feature [5]; but in our case, all these three markers were negative. Hypercalcemia is found in 40 % of the patients for an unknown reason. Excess production of calcitriol by the malignant lymphoma cells is considered a possible cause [14–16].

The exact cause of PHL is unknown, although viruses such as HBV, HCV, and Epstein–Barr virus have been implicated. There appears to be a strong association between primary hepatic NHL and HCV. Hepatitis C is found in 40–60 % of patients with PHL. The possible roles of HCV, cirrhosis, and therapeutic interferon in lymphomagenesis remain hypothetical; however, our patient was not positive for HCV [1, 3, 5, 7]. Conflicting theories exist on the association of HBV infection and PHL [4, 8, 17, 18]. Aozasa et al. [17] have reported a 20 % prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen positivity in a series of 69 patients with PHL, in which 52 patients were from western countries and 17 from Japan. Chronic antigenic stimulation by HBV has been postulated to play a role in the development of PHL [18]. Although it remains uncertain to what extent HBV contributes to the development of PHL, a host environment with impaired immunity might play an important role [19–21]. Since our patient was seropositive for HBV, HBV may have had a role in tumorigenesis.

On ultrasound, PHL lesions are hypoechoic relative to the normal liver. Imaging by CT shows hypo-attenuating lesions and rim enhancement after contrast. Although the findings are variable, a few authors have described hypo-intensity on T1-weighted images and hyper-intensity on T2-weighted images [4].

A definite diagnosis of PHL is difficult to establish on clinical grounds. Hepatocellular carcinoma and metastasis from gastrointestinal carcinoma (mostly colon) present very similarly and are much more common. Normal levels of the tumor markers AFP and CEA are found in almost 100 % of the patients, as was also the case in our patient, with PHL facilitating the differential diagnosis [1]. Liver biopsy remains the most valuable tool for diagnosis of PHL [4]. The diagnosis of PHL requires a liver biopsy compatible with lymphoma and the absence of lymphoproliferative disease outside the liver [1]. If a discrete mass is not visible on imaging for percutaneous liver biopsy (PLB), the transjugular approach may be reasonable [3]. A recent review indicates that transjugular liver biopsy can be used to obtain adequate tissue samples and major complications and mortality rates are similar to PLB [22]. Although most patients are treated with chemotherapy, with some physicians employing a multimodality approach that incorporates surgery and radiotherapy, the optimal treatment of PHL is not yet defined [2]. Chemotherapy protocols for the treatment of lymphomas have changed in the past two decades to multidrug regimens such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), alternating triple-combination therapy (ATT), IMVP-16, OAP (that include etoposide, cytosine arabinoside, and others) [1]. The standard treatment for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the CHOP regimen [1]. Although our patient received the CHOP regimen only without any evidence of tumor recurrence after 15 months of follow-up, the addition of rituximab, a chimeric mouse-human monoclonal antibody targeting the pan-B-cell antigenic marker CD20 (the first monoclonal antibody licensed for use in the treatment of cancer), to the CHOP regimen, when given in 8 cycles, augments the complete response rate and prolongs event-free and overall survival in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, without a clinically significant increase in toxicity [4]. With regard to hepatic MALT lymphomas, reported cases demonstrate that MALT lymphoma is usually limited to the liver and surgical resection cures the patient in most cases [13]. Also, when diagnosis is confirmed after needle biopsy, nonresection treatment procedures would be permitted, such as radiofrequency ablation instead of surgical resection [13].

For patients with diffuse large B-cell NHL (including follicular NHL), several large-scale prospective randomized trials have established prolongation of remission when rituximab is incorporated into first-line treatment [4].

In a report by Yang et al., wherein all study patients underwent surgery for PHL, their univariate analysis revealed that postoperative chemotherapy was the only significant prognostic factor that influenced survival [2]. In a previous study, one patient treated with surgery followed by chemotherapy and radiation was reported to be alive 5 years following the initial diagnosis. Page et al. have stratified several pretreatment risk factors after a retrospective cohort review including the serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, serum b-2 microglobulin (b2M) level, tumor size, constitutional symptoms, and Ann Arbor stage [6]. Lei has proposed that, in patients with localized disease, surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered to prevent disease recurrence [8]. We also suggest that good prognosis of PHL can be obtained by early surgery combined with chemotherapy in strictly selected patients.

The prognosis of PHL was considered very poor with median survival as low as 6 months for patients treated with chemotherapy alone, and longer for patients treated with a combination of modalities [2]. Massive liver infiltration, high index of proliferation, advanced age, constitutional symptoms, bulky disease, unfavorable histologic subtype, elevated LDH levels, cirrhosis, elevated levels of beta-2 microglobulin, and comorbid conditions are poor prognostic factors [4]. Most patients with PHL present with poor prognostic features. One large review of 72 patients has shown the median survival to be 15.3 months (range 0–123.6 months). Yang et al. reported a median overall survival for all nine patients to be 23 months [2]. These results were better than those previously reported, and it could have been due to strict patient selection and the use of postoperative chemotherapy in most patients [2]. Reported cases demonstrate that MALT lymphoma has a favorable prognosis compared with other subtypes of PHL [13]. Since our patient had stage IE disease according to the Ann Arbor staging system, and the pathologic type was marginal B-cell lymphoma (low-grade lymphoma, MALT lymphoma), we expect the prognosis to be favorable with adequate therapy.

Conclusion

PHL should be considered in any patient at any age who presents with a liver mass or infiltration. Although hepatoma or metastatic diseases are common, the presence of B symptoms, and the absence of elevated levels of CEA and AFP should indicate a search for the presence of PHL. If the clinical picture is suspicious for PHL, a liver biopsy should be obtained because the disease is treatable. Although the prognosis is variable, good response to early surgery with postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy can be achieved in strictly selected patients. With addition of new therapeutic drugs such as rituximab to the previous chemotherapy regimen, overall survival has improved for these patients.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- PHL

Primary hepatic lymphoma

- MALT

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

References

- 1.Agmon-Levin N, Berger I, Shtalrid M, Schlanger H, Sthoeger ZM. Primary hepatic lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Age Ageing. 2004;33:637–640. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang XW, Tan WF, Yu WL, Shi S, Wang Y, Zhang YL, et al. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of primary hepatic lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:6016–6019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i47.6016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haider FS, Smith R, Khan S. Primary hepatic lymphoma presenting as fulminant hepatic failure with hyperferritinemia: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2008;2:279. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masood A, Kairouz S, Hudhud KH, Hegazi AZ, Banu A, Gupta NC. Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of liver. Curr Oncol. 2009;16:74–77. doi: 10.3747/co.v16i4.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauduer F, Marty F, Gemain MC, Dulubac E, Bordahandy R. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the liver in a patient with hepatitis B, C. HIV infections. Am J Hematol. 1997;54:265. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199703)54:3<265::AID-AJH17>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Page RD, Romaguera JE, Osborne B, Medeiros LJ, Rodriguez J, North L, et al. Primary hepatic lymphoma: favorable outcome after combination chemotherapy. Cancer. 2001;92:2023–2029. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011015)92:8<2023::AID-CNCR1540>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salmon JS, Thompson MA, Arildsen RC, Greer JP. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma involving the liver: clinical and therapeutic considerations. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2006;6:273–280. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2006.n.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lei KI. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the liver. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;29:293–299. doi: 10.3109/10428199809068566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lei KI, Chow JH, Johnson PJ. Aggressive primary hepatic lymphoma in Chinese patients. Presentation, pathologic features, and outcome. Cancer. 1995;76:1336–1343. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951015)76:8<1336::AID-CNCR2820760807>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameron AM, Truty J, Truell J, Lassman C, Zimmerman MA, Kelly BS, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure from primary hepatic lymphoma: successful treatment with orthotopic liver transplantation and chemotherapy. Transplantation. 2005;80:993–996. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000173999.09381.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osborne BM, Butler JJ, Guarda LA. Primary lymphoma of the liver. Ten cases and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1985;56:2902–2910. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19851215)56:12<2902::AID-CNCR2820561230>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isaacson PG, Banks PM, Best PV, McLure SP, Muller-Hermelink HK, Wyatt JI. Primary low-grade hepatic B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)-type. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:571–575. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199505000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashi M, Yonetani N, Hirokawa F, Asakuma M, Miyaji K, Takeshita A, et al. An operative case of hepatic pseudolymphoma difficult to differentiate from primary hepatic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:3. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avlonitis VS, Linos D. Primary hepatic lymphoma: a review. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:725–729. doi: 10.1080/11024159950189474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erban JK, Tang Z. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 38-2002. A 54-year-old man with hypercalcemia, renal dysfunction, and an enlarged liver. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1952–1960. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc020023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seymour JF, Gagel RF, Hagemeister FB, Dimopoulos MA, Cabanillas F. Calcitriol production in hypercalcemic and normocalcemic patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:633–640. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-9-199411010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aozasa K, Mishima K, Ohsawa M. Primary malignant lymphoma of the liver. Leuk Lymphoma. 1993;10:353–357. doi: 10.3109/10428199309148560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohsawa M, Tomita Y, Hashimoto M, Kanno H, Aozasa K. Hepatitis C viral genome in a subset of primary hepatic lymphomas. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:471–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen HW, Sheu JC, Lin WC, Tsang YM, Liu KL. Primary liver lymphoma in a patient with chronic hepatitis C. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006;105:242–246. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60313-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsiao HH, Liu YC, Hsu JF, Huang CF, Yang SF, Lin SF. Primary liver lymphoma with hypercalcemia: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2009;25:141–144. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70053-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu SJ, Hung CC, Chen CH, Tien HF. Primary effusion lymphoma in three patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. J Clin Virol. 2009;44:81–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalambokis G, Manousou P, Vibhakorn S, Marelli L, Cholongitas E, Senzolo M, et al. Transjugular liver biopsy—indications, adequacy, quality of specimens, and complications—a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2007;47:284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]