Abstract

Melanomas occurring in the tongue are rarer, and when nonpigmented they are often misdiagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma. We report a 50-year-old woman who presented with a 3 × 2 cm soft swelling of mucosal color on the right lateral border of the tongue. The patient had multiple recurrences and was treated by radical radiotherapy, was operated thrice and received adjuvant 5 MIU interferon weekly. During the last surgery, she developed multiple cerebral infarcts and died on the fifth postoperative day. Oral amelanotic melanoma is a very aggressive and potential lethal tumor that often presents as diagnostic dilemma.

Keywords: Tongue oral, Mucosal, Spindle cell tumor, Neoplasm

Introduction

Melanomas of the oral cavity are rare and account for 0.2–8 % of all malignant melanomas [1]. The most frequent site of occurrence is the hard palate followed by the maxillary gingiva [1]. Other oral sites include the mandibular gingiva, buccal mucosa, and floor of the mouth. Melanoma of the tongue is very rare and represents less than 2 % of all oronasal melanomas. The review of literature showed only 31 cases in the Pubmed database. In this article, we report a case of melanoma tongue which was misdiagnosed and treated by radiotherapy as squamous cell carcinoma with complete response and later had multiple recurrences despite multiple excision with clear margin.

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman presented with complaints of swelling on the right lateral margin of the tongue and pain in the right ear of 1-year duration. Clinical examination showed 2 × 3 cm proliferative growth of mucosal color on the right posterolateral part of the tongue with irregular and intact surface. Bilateral ear examinations were within normal limit, and no regional lymphadenopathy was seen. A punch biopsy was taken which was reported as poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. The patient received radical radiotherapy with curative intent. There was complete response to the radiotherapy. However 6 months later, she presented with 5 × 5 cm ulceroproliferative growth on the right lateral border of the tongue which was tender and firm in consistency (Fig. 1). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed a right anterolateral tongue mass with high intensity. There was no significant cervical lymphadenopathy. A diagnosis of recurrent carcinoma of the tongue was made, and she was treated with wide local excision and supraomohyoid block dissection. The histopathology of the resected specimen showed a malignant neoplasm composed of spindle cells arranged in fascicles and sheets and ulceration of the mucosa (Fig. 2). No evidence of pigment or squamous differentiation was seen in the tumor. The tumor infiltrated the underlying lingual muscle deeply. The lateral margin was 2 mm (microscopic) away from the tumor; the rest of the entire margin and base was free from the tumor. A total of 25 lymph nodes were dissected which were all free of metastasis. The differential diagnoses of sarcomatoid carcinoma and pleomorphic sarcoma were considered. Immunohistochemistry test was negative for low- and high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, vimentin, and desmin, while tumor cells were focally and weakly positive for HMB45 (Fig. 3). A diagnosis of the melanoma tongue was made. The patient had an uneventful recovery and started on 5 MIU interferon weekly. Four months later the patient developed an ulcerative growth measuring 6 cm × 8 cm on the right gingivobuccal sulcus which was friable and very vascular (Fig. 4). There was no lymphadenopathy present. Wide local excision and segmental mandibulectomy were done. Histopathology reports showed the poorly differentiated malignant tumor; however, possibility of amelanotic melanoma was not ruled out (Figs. 5 and 6). The entire resected margin was free of the tumor. The patient made a good postoperative recovery. One month later, the patient presented with another recurrent mass at the same site. Evaluation of the base of the skull, carotids, and pterygoids could not be done as the patient was not able to afford CT scan. Intraoperatively the tumor was seen to infiltrate every fascial plane, infiltrating the internal carotid and infratemporal fossa. Clearance could be achieved with difficulty. There was inadvertent injury of internal carotid artery which was repaired. After wide excision, reconstruction was done with pectoralis major myocutaneous flap. On the second postoperative day, the patient developed left-sided hemiparesis and became unconscious. CT scan of the brain showed multiple cerebral infarcts. Despite supportive measures, the patient succumbed to her illness on the fifth postoperative day.

Fig. 1.

Clinical photograph showing recurrent lesion on tongue

Fig. 2.

Photomicrograph showing poorly differentiated malignant neoplasm (hematoxylin and eosin × 40)

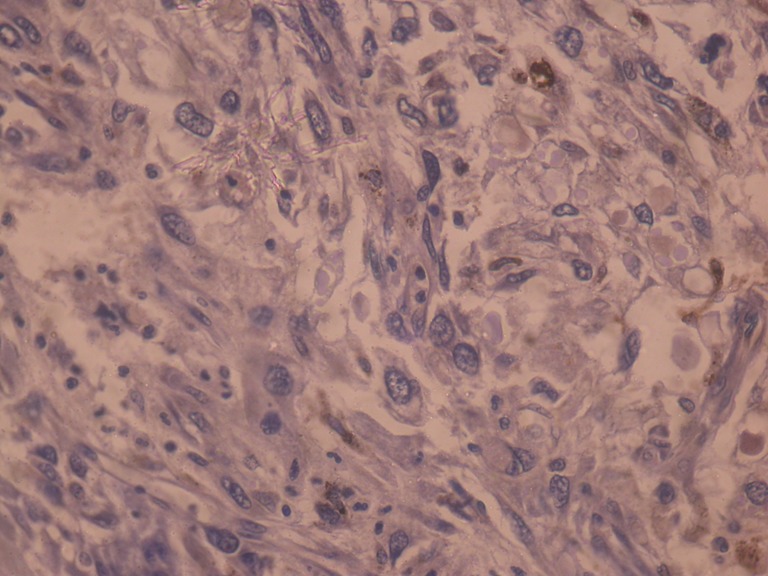

Fig. 3.

Photomicrograph showing focal HMB-45 staining (HMB-45 × 400)

Fig. 4.

Computerized tomography of the recurrent lesion showing lesion at lower alveolus, buccogingival sulcus, and gingivolabial sulcus

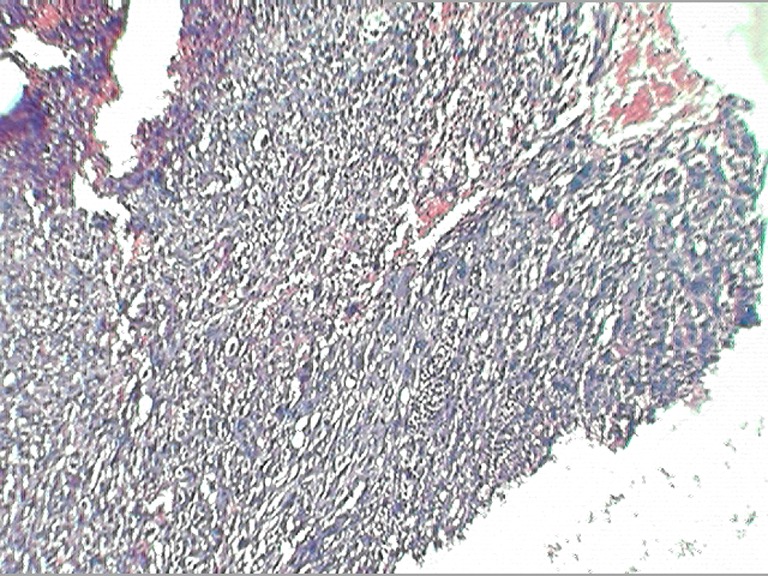

Fig. 5.

Photomicrograph showing poorly differentiated spindle cell neoplasm (hematoxylin and eosin ×40)

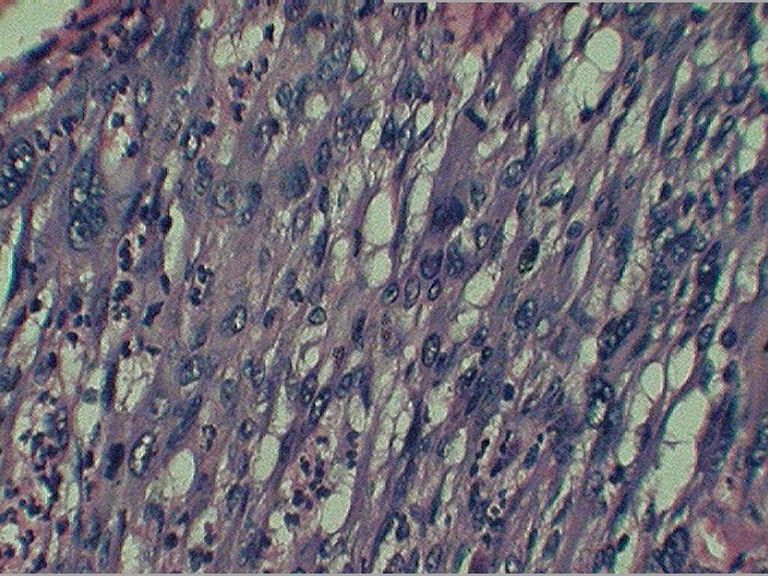

Fig. 6.

Photomicrograph showing the same neoplasm under high power (hematoxylin and eosin ×400)

Discussion

Less than 10 % of the melanomas arise in extracutaneous sites. In a review of the large studies, the melanoma of the oral cavity is reported to account for 0.2–8 % of all melanomas [1, 2]. Oral melanoma is more common in the Japanese than in other groups. Tumors are commonly found in patients older than 40 years and there are no significant differences between genders [1, 3–6]. Oral melanoma is a rare entity and it is very unusual to be located on the tongue. A review of literature revealed only 31 such cases of tongue melanoma. The etiology of mucosal melanoma is not clear; however, p53 mutations [7], loss of heterozygosity [8], and expression of DNA repair protein have been reported [9].

They are easily diagnosed clinically as they are pigmented and have an irregular shape and outline and often painless in their early presentation [4, 5, 10]. However, our patient presented with pain in the right ear and swelling which was proliferative and later became ulceroproliferative and was of mucosal color. Bleeding occurs in melanoma until late in the disease. This patient presented with hemoglobin of 5 or 6 g/dl and with oral bleeding.

Amelanotic melanoma accounts for 5–35 % of oral melanomas. This melanoma appears in the oral cavity as a mucosa-colored mass. The lack of pigmentation contributes to clinical and histologic misdiagnosis. HMB-45 staining has been reported to be more sensitive than S-100 staining [11]. Other immunohistochemical markers such as melan A, PLN-2, and MITF are also positive in up to 50 % of the cases [12]. c-Kit expression has also been reported in mucosal melanomas [13].

Ablative surgery with tumor-free margins remains the treatment of choice [14]. In our patient, recurrence occurred despite the reported tumor-free margin on both the times. After complete surgical excision, the local–regional relapse rate is reported to be 10–20 %, and 5-year survival is about 10–25 %, with a reported range of 4.5–48 % [15]. The spindle-shaped architecture of the melanoma has very dismal prognosis; however, the melanoma in oral mucosa is very aggressive with any architecture or cell types [16]. Although radiation alone is reported to have questionable benefit (particularly in small fractionated doses), it is a valuable adjuvant in achieving relapse-free survival when high-fractionated doses are used [17–20]. Experience with oral malignant melanoma is largely derived from single cases. Anecdotal reports describe success with interferon-α (INF-α) or hyperfractionated radiation therapy. Many cancer centers follow surgical excision with a course of IL-2 as adjunctive therapy to prevent or limit recurrence [21]. Multimodality therapy may prove effective in the treatment of oral mucosal melanoma. The prognosis for patients with oral malignant melanoma is poor, with the 5-year survival rate at 11–18 % [1, 3, 4, 22, 23]. Early recognition and treatment greatly improves the prognosis. Late discovery and diagnosis often indicate the existence of an extensive tumor with metastasis. After surgical resection, recurrence and metastasis are frequent events, and most patients die of the disease in 2 years. The best option for survival is the prevention of metastasis by surgically excising any recurrent tumor.

Conclusion

Melanoma tongue is a rarity and may present as a nonpigmented lesion which may be confused with squamous cell carcinoma. Amelanotic lesions of the oral cavity are diagnostic challenge to the head and neck surgeon. If they are spindle-cell types, they may be erroneously reported as squamous carcinoma; a high index of suspicion and application of a panel of immunohistochemical markers are important for correct diagnosis and choosing the right therapeutic strategy.

References

- 1.Pandey M, Mathew A, Iype EM, Sebastian P, Abraham EK, Nair KM. Primary malignant mucosal melanoma of the head and neck region: pooled analysis of 60 published cases from India and review of literature. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2002;11(1):3–10. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200202000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gondivkar SM, Indurkar A, Degwekar S, Bhowate R. Primary oral malignant melanoma–a case report and review of the literature. Quintessence Int. 2009;40(1):41–46. doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a14113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLean N, Tighiouart M, Muller S. Primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Comparison of clinical presentation and histopathologic features of oral and sinonasal melanoma. Oral Oncol. 2008;44(11):1039–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meleti M, Leemans CR, de Bree R, Vescovi P, Sesenna E, van der Waal I. Head and neck mucosal melanoma: experience with 42 patients, with emphasis on the role of postoperative radiotherapy. Head Neck. 2008;30(12):1543–1551. doi: 10.1002/hed.20901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner M, Morris CG, Werning JW, Mendenhall WM. Mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008;31(1):43–48. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318134ee88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manolidis S, Donald PJ. Malignant mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: review of the literature and report of 14 patients. Cancer. 1997;80(8):1373–1386. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19971015)80:8<1373::AID-CNCR3>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gwosdz C, Scheckenbach K, Lieven O, Reifenberger J, Knopf A, Bier H, Balz V. Comprehensive analysis of the P53 status in mucosal and cutaneous melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(3):577–582. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takagi R, Nakamoto D, Mizoe JE, Tsujii H. LOH analysis of free DNA in the plasma of patients with mucosal malignant melanoma in the head and neck. Int J Clin Oncol. 2007;12(3):199–204. doi: 10.1007/s10147-006-0650-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marani C, Alvino E, Caporali S, Vigili MG, Mancini G, Rahimi S. DNA mismatch repair protein expression and microsatellite instability in primary mucosal melanomas of the head and neck. Histopathology. 2007;50(6):780–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradley PJ. Primary malignant mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;14(2):100–104. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000193176.54450.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu CH, Chen HH, Liu CM, Jeng YM, Wang JT, Wang YP, Liu BY, Sun A, Chiang CP. HMB-45 may be a more sensitive maker than S-100 or melan-A for immunohistochemical diagnosis of primary oral and nasal mucosal melanomas. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34(9):540–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris LG, Wen YH, Nonaka D, DeLacure MD, Kutler DI, Huan Y, Wang BY. PNL2 melanocytic marker in immunohistochemical evaluation of primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2008;30(6):771–775. doi: 10.1002/hed.20785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satzger I, Schaefer T, Kuettler U, Broecker V, Voelker B, Ostertag H, Kapp A, Gutzmer R. Analysis of C-KIT expression and KIT gene mutation in human mucosal melanomas. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(12):2065–2069. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penel N, Mallet Y, Mirabel X, Van JT, Lefebvre JL. Primary mucosal melanoma of head and neck: prognostic value of clear margins. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(6):993–995. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000217236.06585.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKinnon JG, Kokal WA, Neifeld JP, Kay S. Natural history and treatment of mucosal melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 1989;41(4):222–225. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930410406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prasad ML, Patel S, Hoshaw-Woodard S, Escrig M, Shah JP, Huvos AG, Busam KJ. Prognostic factors for malignant melanoma of the squamous mucosa of the head and neck. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26(7):883–892. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakashima JP, Viegas CM, Fassizoli AL, Rodrigues M, Chamon LA, Silva JH, Dias FL, Araujo CM. Postoperative adjuvant radiation therapy in the treatment of primary head and neck mucosal melanomas. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2008;70(6):344–351. doi: 10.1159/000163029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krengli M, Masini L, Kaanders JH, Maingon P, Oei SB, Zouhair A, Ozyar E, Roelandts M, Amichetti M, Bosset M, Mirimanoff RO. Radiotherapy in the treatment of mucosal melanoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: analysis of 74 cases. A rare cancer network study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(3):751–759. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wada H, Nemoto K, Ogawa Y, Hareyama M, Yoshida H, Takamura A, Ohmori K, Hamamoto Y, Sugita T, Saitoh M, Yamada S. A multi-institutional retrospective analysis of external radiotherapy for mucosal melanoma of the head and neck in northern Japan. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59(2):495–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owens JM, Roberts DB, Myers JN. The Role of postoperative adjuvant radiation therapy in the treatment of mucosal melanomas of the head and neck region. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(8):864–868. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.8.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartell HL, Bedikian AY, Papadopoulos NE, Dett TK, Ballo MT, Myers JN, Hwu P, Kim KB. Biochemotherapy in patients with advanced head and neck mucosal melanoma. Head Neck. 2008;30(12):1592–1598. doi: 10.1002/hed.20910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bachar G, Loh KS, O’Sullivan B, Goldstein D, Wood S, Brown D, Irish J. Mucosal melanomas of the head and neck: experience of the princess margaret hospital. Head Neck. 2008;30(10):1325–1331. doi: 10.1002/hed.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krengli M, Masini L, Kaanders JH, Maingon P, Oei SB, Zouhair A, Ozyar E, Roelandts M, Amichetti M, Bosset M, Mirimanoff RO. Radiotherapy in the treatment of mucosal melanoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: analysis of 74 cases. A rare cancer network study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(3):751–759. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]