Abstract

Objective

To analyse gender differences in the relationship of individual social class, employment status and neighbourhood unemployment rate with present type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Design

Five cross-sectional studies.

Setting

Studies were conducted in five regions of Germany from 1997 to 2006.

Participants

The sample consisted of 8871 individuals residing in 226 neighbourhoods from five urban regions.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Prevalent T2DM.

Results

We found significant multiplicative interactions between gender and the individual variables–—social class and employment status. Social class was statistically significantly associated with T2DM in men and women, whereby this association was stronger in women (lower vs higher social class: OR 2.68 (95% CIs 1.66 to 4.34)) than men (lower vs higher social class: OR 1.78 (95% CI 1.22 to 2.58)). Significant associations of employment status and T2DM were only found in women (unemployed vs employed: OR 1.73 (95% CI 1.02 to 2.92); retired vs employed: OR 1.77 (95% CI 1.10 to 2.84); others vs employed: OR 1.64 (95% CI 1.01 to 2.67)). Neighbourhood unemployment rate was associated with T2DM in men (high vs low tertile: OR 1.52 (95% CI 1.18 to 1.96)). Between-study and between-neighbourhood variations in T2DM prevalence were more pronounced in women. The considered covariates helped to explain statistically the variation in T2DM prevalence among men, but not among women.

Conclusions

Social class was inversely associated with T2DM in both men and women, whereby the association was more pronounced in women. Employment status only affected T2DM in women. Neighbourhood unemployment rate is an important predictor of T2DM in men, but not in women.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Public Health

Article summary.

Article focus

The aim of this study was to examine disparities in the association of individual social class, employment status and neighbourhood unemployment rate with prevalent type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) by gender in a pooled analysis of five population-based regional studies.

Key messages

Social class was statistically significantly associated with T2DM among women and men; however, the association was stronger in women than in men; in particular, individual employment status is an important determinant of T2DM in women.

Between-study and between-neighbourhood variances in T2DM were more pronounced in women, as already observed for obesity.

Neighbourhood unemployment rate was only associated with T2DM in men after adjustment for individual variables.

Strength and limitations of this study

Data of five population-based representative studies were applied, linking data on the prevalence of T2DM to small areas and regions.

This study adds knowledge to the research on the interaction of gender, social determinants and health at different levels.

The limitations were as follows: the cross-sectional design does not allow causal conclusions; T2DM was based on a self-reported physician's diagnosis; administrative definitions of neighbourhoods could result in exposure misclassification and underestimation of neighbourhood effects; problem of residential selection.

Introduction

Gender differences in health inequality vary by the studied health outcome, the measure of social status and the stage of life course.1–3 A systematic review of 23 case–control and cohort studies on socioeconomic differences in the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) concluded that inequality in the risk of T2DM was stronger in women than in men.4 However, the results are diverse with respect to the magnitude in the association of T2DM and social status in men: a number of studies have shown associations among both men and women,5–8 but there have also been studies published reporting associations only in women.9 10 With respect to occupational status, contrasting results have been presented by Kumari et al11 and Maty et al.12 For instance, the first study showed a stronger inverse relationship between the civil service employment grade and the incidence of T2DM in men, applying data of the Whitehall study II.11

Beyond an individual's social class, socioeconomic characteristics of the neighbourhood affect health.13–15 As part of the Diabetes Collaborative Research of Epidemiologic Studies (DIAB-CORE) in Germany, Schipf et al reported regional disparities in the age-standardised prevalence of T2DM.16 In two recent studies, we found that the prevalence of T2DM varied across regions in Germany, even after adjustment of individual characteristics. These variations could in part be explained statistically by the neighbourhood unemployment rate within cities or by regional deprivation.17 18

Gender differences may arise out of different exposures to social, psychosocial and behavioural determinants of health (‘differential exposure hypothesis’). Another explanation might be a different vulnerability to health determinants, characteristics of the neighbourhood and reaction to material, behavioural and psychosocial conditions of men and women (‘differential vulnerability hypothesis’).2 19 Differences in men's and women's perception of the neighbourhood context and social status may as well be a source of health disparities.19 Stafford et al19 examined gender differences in the relationship between self-rated health and the neighbourhood context and found a larger impact of the neighbourhood context on the health of women.

The aims of this study were (1) to investigate if the association of individual social class, individual employment status and neighbourhood unemployment rate with prevalent T2DM differs for men and women in a pooled analysis of five population-based regional studies and (2) to examine the extent to which the prevalence of T2DM varies by gender between neighbourhoods and regions in Germany. In a subanalysis, we performed study-specific calculations of the relationship between T2DM and social class in men and women.

Methods

Within the DIAB-CORE, the cross-sectional data of five regional studies were pooled: the Cardiovascular Disease, Living and Ageing in Halle Study (CARLA), the Dortmund Health Study (DHS), the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study (HNR), the Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg (KORA) S4 Study and the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP). Data collection was conducted between 1997 and 2006. The studies have similar study designs (population-based), sampling procedures (two-stage cluster or stratified random sampling) and response proportions (56–69%). The studies were approved by local ethics committees and informed written consent was obtained from the participants in the study. Within the five studies, similar instruments, questionnaires and medical measurements were applied to collect data. Study designs have been described elsewhere in more detail.20–24

In brief, data on 11 688 participants aged 45–74 years were provided. Of these participants, 2280 individuals living in rural areas of KORA and SHIP were excluded from the sample because they could not be assigned to spatial units below the level of municipalities; hence our study was limited to urban areas. Study participants were assigned to neighbourhoods via addresses of residence at baseline (8 participants could not be linked). These neighbourhoods were defined by administrative units: statistical administrative units (subdivision of city districts) in HNR and DHS, city districts in CARLA, planning regions (summary of city districts) in KORA and postal code areas in SHIP. Participants resided in 227 of the total 236 neighbourhoods in the five study regions. After further exclusion of participants with missing information on individual characteristics (n=529), the final sample consisted of 8871 residents in 226 neighbourhoods.

On the basis of the definition of the DIAB-CORE Consortium,25 a T2DM case was defined as a self-reported physician-diagnosed T2DM or self-reported T2DM treatment (insulin, oral antidiabetic agents, dietary treatment). Participants reporting an age at diagnosis of 30 years or younger were excluded from the analyses to avoid inclusion of possible cases of type 1 diabetes.

Social class was measured with a summary score of income and education. Its operationalisation was derived from the Winkler-Index of Socioeconomic Status,26 which summarises information on individual educational and professional attainment, net household income and the occupational position of the main earner of a household. The three dimensions are transformed to an ordinal scale ranging from 1 to 7 and summed up to an index with a scale from 3 to 21 points. Since the information on occupational status was not available for our analysis, the index was solely based on education and income, ranging between 2 and 14 points. The index was divided into three groups: higher social class, middle social class and lower social class. Study participants were classified into four employment status groups: employed, retired and unemployed individuals as well as persons with other forms of employment, including participants in vocational retraining, housewives and housemen.

Neighbourhood unemployment rate was applied as a proxy for the socioeconomic status of the neighbourhoods and was calculated as the number of unemployed residents in relation to the working-age population (aged 15–64), obtained from the statistical offices of each considered city. The median year of the data collection period of each study was used as the reference year. A number of studies applied unemployment rate as a measure of deprivation and it was proven to be a strong predictor of health outcomes.22 27–29 Campbell et al30 highlighted that unemployment rate is a simple and good indicator for social and material deprivation, which is regularly updated and easily accessible. For our analysis, equally sized tertiles of the study-specific neighbourhood unemployment rate was used to detect a potential dose–response relationship. Hereafter, the authors refer to the low, medium and high levels of unemployment rate in relative terms, which however corresponds to considerably different levels of unemployment rate across study regions.

The variable marital status summarised information whether a study participant lived with or without a partner. Moreover, lifestyle variables including smoking status (current smoker; former smoker; never smoker), physical exercise (physical exercise; no physical exercise), body mass index (BMI; <30 kg/m²; ≥30 kg/m²) and alcohol consumption (no or moderate intake: women: ≤20 g/day; men: ≤40 g/day; high intake: women: >20 g/day; men: >40 g/day) were considered. Physical exercise was measured as hours spent per week on all kinds of exercise training excluding low-level exercise like walking. Owing to the homogenisation procedure, physical exercise was operationalised as any exercise irrespective of the frequency and duration. All variables were constructed following the DIAB-CORE standard procedures for the homogenisation of basic variables to ensure a high degree of comparability.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis included the calculation of crude and age-adjusted prevalence of T2DM (derived from a logistic regression) and corresponding 95% CIs by gender for individual variables and neighbourhood unemployment rate.

Our data set had a hierarchical structure including individuals (level 1), nested within neighbourhoods (level 2), which were nested in study regions (level 3). To account for this data structure in our statistical analysis, multilevel modelling methods were applied. We conducted a series of mixed effects logistic regression models. First, we tested for interactions between gender and individual social class, employment status and neighbourhood unemployment rate. To do so, we estimated regression models including terms for gender and social class, employment status or neighbourhood unemployment rate as main effects and an interaction term for the effect of social class, employment status or neighbourhood unemployment rate by gender. Second, gender-stratified analyses were conducted with a stepwise modelling strategy. The models were adjusted for the confounding variables age, marital status and the remaining social variables (social class/employment status/neighbourhood unemployment rate) depending on the variable of interest. Lifestyle factors, including smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI and physical exercise, were evaluated as potential mediators in the relationship between T2DM and individual social class, employment status or neighbourhood unemployment rate. The results were presented as ORs with corresponding 95% CIs.

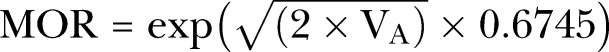

Random effects were included to capture between-study and between-neighbourhood variance reported as median ORs (MOR). The latter represents a transformation of the area-level variation (VA on an OR-scale). MOR gives the median value of all ORs between a randomly chosen highest-risk area and lowest-risk area and was calculated on the level of neighbourhoods and study regions with the following equation:  , where 0.6745 is the 75th centile of the cumulative distribution function of the normal distribution with mean 0 and variance 1.31

32

, where 0.6745 is the 75th centile of the cumulative distribution function of the normal distribution with mean 0 and variance 1.31

32

Study-specific analyses were performed and analysed with meta-analytical tools. Owing to the small number of cases by study, the social class variable had to be applied as a continuous measure in this subanalysis (ranging between two points, highest social class, and 14 points, lowest social class). For this purpose, inverse-variance weighting was used to estimate fixed and random effects summary estimates and displayed in forest plots.33 Q-statistic and I² index were applied to assess heterogeneity and the extent of heterogeneity between study results, respectively.34 Analyses were performed in STATA/SE V.11.0.

Results

In total, 8871 participants residing in 226 neighbourhoods from five urban regions were included in our analysis. Characteristics of the five studies are displayed in table 1. The crude T2DM prevalence was statistically significantly lower among women than men, 7.5% (95% CI 6.7 to 8.3) versus 10% (95% CI 9.1 to 10.9; significance derived from 95% CI). This pattern was observed in all five regional studies. Sociodemographic characteristics are reported in table 2. Compared with men, women belonged more often to the lower or middle social class and a higher proportion was not employed, except in SHIP. A higher proportion of women than men reported living without a partner.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the five population-based studies (CARLA, DHS, KORA, HNR and SHIP, Germany, 1997–2006)

| CARLA | DHS | KORA | HNR | SHIP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study period | 12/2002–01/2006 | 09/2003–06/2004 | 10/1999–04/2001 | 12/2000–06/2003 | 10/1997–03/2001 |

| Federal state (region) | Saxony-Anhalt (east) | North Rhine-Westphalia (west) | Bavaria (south) | North Rhine-Westphalia (west) | Mecklenburg-West Pomerania (northeast) |

| Sampling | Stratified random sampling | Stratified random sampling | Two-stage cluster sampling | Stratified random sampling | Two-stage cluster sampling |

| Cities | Halle (Saale) | Dortmund | Augsburg | Bochum, Essen, Mülheim | Greifswald, Stralsund |

| Neighbourhoods (n)/types | 43/city districts | 62/statistical administrative units | 17/planning regions | 108/ statistical administrative units | 6/clusters of city districts |

| Total regional population (neighbourhood range) | 238 078 (18–19 210) | 587 607 (476–25 686) | 252 725 (2730–37 246) | 1 142 112 (262–32 466) | 115 962 (5230–31 154) |

| Unemployment rate (%; neighbourhood range)* | 14.1 (3.9–22.5) | 15.3 (5.0–27.7) | 4.8 (1.9–7.6) | 7.5 (1.7–13.5) | 13.1 (9.9–14.9) |

*Data on neighbourhood unemployment were collected in the year 1999 in SHIP, in 2000 in KORA, in the year 2001 in HNR and in 2003 in CARLA and DHS.

CARLA, Cardiovascular Disease, Living and Ageing in Halle Study; DHS, Dortmund Health Study; HNR, Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study; KORA, Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg; SHIP, S4 Study and the Study of Health in Pomerania.

Table 2.

Participants’ characteristics in the five population-based studies (CARLA, DHS, KORA, HNR, SHIP, Germany, 1997–2006)

| Study | CARLA |

DHS |

KORA |

HNR |

SHIP |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Participants 45–74 with full information | 719 | 638 | 414 | 411 | 533 | 494 | 2257 | 2175 | 615 | 615 |

| Number of neighbourhoods (range of residing participants) | 37 (3–139) | 60 (1–42) | 17 (13–141) | 106 (1–140) | 6 (95–396) | |||||

| Crude diabetes prevalence (%) (95% CI) | 12.9 (10.6 to 15.6) | 12.1 (9.6 to 14.9) | 11.8 (8.9 to 15.3) | 7.8 (5.4 to 10.8) | 7.1 (5.1 to 9.7) | 5.5 (3.6 to 7.9) | 8.9 (7.8 to 10.2) | 5.9 (5.0 to 7.0) | 11.7 (9.3 to 14.5) | 9.6 (7.4 to 12.2) |

| Mean age (SD) | 61.0 (8.0) | 60.4 (7.7) | 60.9 (8.4) | 59.7 (8.5) | 58.9 (8.6) | 58.8 (8.4) | 59.5 (7.8) | 59.4 (7.8) | 60.3 (8.3) | 58.8 (8.3) |

| Social class % (n) | ||||||||||

| Lower | 7.4 (53) | 13.0 (83) | 11.1 (46) | 23.8 (98) | 6.0 (32) | 16.4 (81) | 6.2 (140) | 19.7 (429) | 12.2 (75) | 26.0 (160) |

| Middle | 61.3 (441) | 65.1 (415) | 46.1 (191) | 46.2 (190) | 48.4 (258) | 54.1 (267) | 53.0 (1195) | 55.9 (1215) | 67.3 (414) | 63.1 (388) |

| Higher | 31.3 (225) | 21.9 (140) | 42.8 (177) | 29.9 (123) | 45.6 (243) | 29.6 (146) | 40.9 (922) | 24.4 (531) | 20.5 (126) | 10.9 (67) |

| Employment status % (n) | ||||||||||

| Employed | 34.9 (251) | 30.6 (195) | 38.7 (160) | 34.8 (143) | 50.3 (268) | 35.0 (173) | 46.4 (1047) | 31.9 (693) | 33.3 (205) | 35.1 (216) |

| Retired | 48.1 (346) | 52.0 (332) | 51.9 (215) | 33.8 (139) | 43.0 (229) | 39.3 (194) | 47.6 (1075) | 37.4 (813) | 54.0 (332) | 49.6 (305) |

| Unemployed | 15.2 (109) | 12.4 (79) | 7.3 (30) | 6.1 (25) | 6.4 (34) | 8.9 (44) | 5.7 (129) | 7.5 (162) | 12.4 (76) | 14.5 (89) |

| Others | 1.8 (13) | 5.0 (32) | 2.2 (9) | 25.3 (104) | 0.4 (2) | 16.8 (83) | 0.3 (6) | 23.3 (507) | 0.3 (2) | 0.8 (5) |

| Marital status (%) | ||||||||||

| Living with a partner | 89.0 (640) | 73.4 (468) | 86.7 (359) | 71.5 (294) | 82.4 (439) | 67.2 (332) | 90.2 (2035) | 74.7 (1624) | 88.3 (543) | 68.8 (423) |

| Living without a partner | 11.0 (79) | 26.7 (170) | 13.3 (55) | 28.5 (117) | 17.6 (94) | 32.8 (162) | 9.8 (222) | 25.3 (551) | 11.7 (72) | 31.2 (192) |

CARLA, Cardiovascular Disease, Living and Ageing in Halle Study; DHS, Dortmund Health Study; HNR, Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study; KORA, Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg; SHIP, S4 Study and the Study of Health in Pomerania.

The age-adjusted prevalence of T2DM was statistically significantly lower in higher social class women and men than in the lower social class (4.7% (95% CI 3.8 to 5.6), respectively, 9.7% (95% CI 8.3 to 11.5) in women; 6.9% (95% CI 5.9 to 8.1), respectively, 14.2% (95% CI 11.8 to 16.8) in men; table 3). Women had a statistically significantly lower age-adjusted T2DM prevalence than men over all social classes. Employed men had a statistically significantly lower age-adjusted T2DM prevalence with 7.3% (95% CI 6.2 to 8.7) than retired men with 10.2% (95% CI 8.8 to 11.7). Across neighbourhoods, the highest age-adjusted prevalence of T2DM was found in women and men living in neighbourhoods with a high unemployment rate (8.3% (95% CI 7.2 to 9.5), respectively, 10.9% (95% CI 9.6 to 12.3)). Individuals living without a partner showed statistically significantly higher prevalence than individuals who lived with a partner, irrespective of gender. Being physically inactive or having a BMI of 30 or above was statistically significantly associated with a higher T2DM prevalence in men and women.

Table 3.

Gender-stratified crude and age-adjusted prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus by individual variables and neighbourhood unemployment rate with data from five population-based studies (CARLA, DHS, KORA, HNR, SHIP, Germany, 1997–2006)*

| Men |

Women |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude prevalence |

Age-adjusted prevalence |

Crude prevalence |

Age-adjusted prevalence |

|||||||||

| N | T2DM cases | Per cent | 95% CI | Per cent | 95% CI | N | T2DM cases | Per cent | 95% CI | Per cent | 95% CI | |

| Social class | ||||||||||||

| Lower | 346 | 57 | 16.5 | 12.7 to 20.8 | 14.2 | 11.8 to 16.8 | 851 | 104 | 12.2 | 10.1 to 14.6 | 9.7 | 8.3 to 11.5 |

| Middle | 2499 | 267 | 10.7 | 9.5 to 12.0 | 9.7 | 8.7 to 10.8 | 2475 | 194 | 7.8 | 6.8 to 9.0 | 6.6 | 5.8 to 7.5 |

| Higher | 1693 | 129 | 7.6 | 6.4 to 9.0 | 6.9 | 5.9 to 8.1 | 1007 | 26 | 2.6 | 1.7 to 3.8 | 4.7 | 3.8 to 5.6 |

| Employment status | ||||||||||||

| Employed | 1931 | 126 | 6.5 | 5.5 to 7.7 | 7.3 | 6.2 to 8.7 | 1420 | 39 | 2.8 | 2.0 to 3.7 | 5.5 | 4.6 to 6.7 |

| Retired | 2197 | 290 | 13.2 | 11.8 to 14.7 | 10.2 | 8.8 to 11.7 | 1783 | 213 | 11.9 | 10.5 to 13.5 | 7.8 | 6.6 to 9.1 |

| Unemployed | 378 | 32 | 8.5 | 5.9 to 11.7 | 10.3 | 8.0 to 13.2 | 399 | 26 | 6.5 | 4.3 to 9.4 | 7.8 | 6.0 to 10.2 |

| Others | 32 | 5 | 15.6 | 5.3 to 32.8 | 8.7 | 6.4 to 11.6 | 731 | 46 | 6.3 | 4.6 to 8.3 | 6.6 | 5.0 to 8.6 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Living with a partner | 4016 | 387 | 9.6 | 8.7 to 10.6 | 8.7 | 7.9 to 9.5 | 3141 | 199 | 6.3 | 5.5 to 7.2 | 6.2 | 5.4 to 7.0 |

| Living without a partner | 522 | 66 | 12.6 | 9.9 to 15.8 | 11.5 | 9.7 to 13.6 | 1192 | 125 | 10.5 | 8.8 to 12.4 | 8.3 | 7.1 to 9.7 |

| Physical exercise | ||||||||||||

| Physical exercise | 2474 | 194 | 7.8 | 6.8 to 9.0 | 7.5 | 6.6 to 8.4 | 2266 | 136 | 6.0 | 5.1 to 7.1 | 5.5 | 4.8 to 6.3 |

| No physical exercise | 2013 | 258 | 12.8 | 11.4 to 14.4 | 10.9 | 9.8 to 12.2 | 1990 | 178 | 8.9 | 7.7 to 10.3 | 8.1 | 7.2 to 9.2 |

| Smoking | ||||||||||||

| Never smoked | 1370 | 113 | 8.2 | 6.8 to 9.8 | 8.4 | 7.2 to 9.7 | 2502 | 208 | 8.3 | 7.3 to 9.5 | 6.5 | 5.7 to 7.4 |

| Ex-smoker | 2067 | 241 | 11.7 | 10.3 to 13.1 | 9.5 | 8.5 to 10.8 | 936 | 72 | 7.7 | 6.1 to 9.6 | 7.5 | 6.3 to 8.8 |

| Current smoker | 1050 | 98 | 9.3 | 7.6 to 11.3 | 8.7 | 7.3 to 10.3 | 815 | 34 | 4.2 | 2.9 to 5.8 | 6.8 | 5.6 to 8.2 |

| BMI | ||||||||||||

| <30 | 3220 | 260 | 8.1 | 7.2 to 9.1 | 6.6 | 5.8 to 7.4 | 2996 | 123 | 4.1 | 3.4 to 4.9 | 4.7 | 4.1 to 5.4 |

| ≥30 | 1267 | 192 | 15.2 | 13.2 to 17.2 | 15.4 | 13.8 to 17.3 | 1260 | 191 | 15.2 | 13.2 to 17.3 | 11.4 | 10.0 to 12.9 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||||

| No or moderate intake | 3974 | 414 | 10.4 | 9.5 to 11.4 | 9.2 | 8.4 to 10.2 | 4018 | 303 | 7.5 | 6.7 to 8.4 | 6.8 | 6.1 to 7.6 |

| High intake | 513 | 38 | 7.4 | 5.3 to 10.0 | 7.4 | 5.6 to 9.6 | 238 | 11 | 4.6 | 2.3 to 8.1 | 5.4 | 4.0 to 7.3 |

| Unemployment rate | ||||||||||||

| Low | 1519 | 125 | 8.2 | 6.9 to 9.7 | 7.4 | 6.4 to 8.6 | 1384 | 85 | 6.1 | 4.9 to 7.5 | 5.6 | 4.8 to 6.6 |

| Medium | 1579 | 144 | 9.1 | 7.7 to 10.6 | 8.7 | 7.6 to 9.9 | 1527 | 120 | 7.9 | 6.6 to 9.3 | 6.6 | 5.7 to 7.6 |

| High | 1440 | 184 | 12.8 | 11.1 to 14.6 | 10.9 | 9.6 to 12.3 | 1422 | 119 | 8.4 | 7.0 to 9.9 | 8.3 | 7.2 to 9.5 |

*Age-adjusted prevalence is derived from logistic regression models.

BMI, body mass index; CARLA, Cardiovascular Disease, Living and Ageing in Halle Study; DHS, Dortmund Health Study; HNR, Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study; KORA, Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg; SHIP, S4 Study and the Study of Health in Pomerania; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

In the fully adjusted multivariable analyses, the interaction terms of social class and gender were statistically significant. Among the employment status groups, we found significant multiplicative interactions between unemployed individuals and gender as well as between retired individuals and gender. The interaction terms between the neighbourhood unemployment rate and gender were not statistically significant.

The results of the gender-stratified multivariable regression analysis are presented in table 4. Among women and men, we found a statistically significant association of social class and T2DM. The social gradient in the odds of T2DM was reduced when the models were adjusted for age and the confounding variables. This reduction was particularly large in women. Overall, the association between social class and T2DM was stronger in women (lower vs higher social class: OR 2.68 (95% CI 1.66 to 4.34)) than men (lower vs higher social class: OR 1.78 (95% CI 1.22 to 2.58); model 3, table 4). Significant associations of employment status and T2DM were only found in women: In reference to employed women, unemployed women, retired women and women with other employment status had 1.73 (95% CI 1.02 to 2.92), 1.77 (95% CI 1.10 to 2.84) and 1.64 (95% CI 1.01 to 2.67) times higher odds of having T2DM (model 3, table 4). The significantly elevated odds of T2DM in retired men were dissolved by adjustment for age.

Table 4.

Gender-stratified multilevel logistic regression of type 2 diabetes mellitus by individual social class, employment status and neighbourhood unemployment rate*, †, ‡

| Social class (reference: higher social class) |

Employment status (reference: employed) |

Unemployment rate (reference: low unemployment rate) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle | Lower | Retired | Unemployed | Others | Medium | High | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Model 1§ | |||||||

| Women | 3.11 (2.04 to 4.73) | 5.37 (3.44 to 8.40) | 4.71 (3.31 to 6.69) | 2.36 (1.41 to 3.95) | 2.65 (1.69 to 4.14) | 1.45 (1.03 to 2.04) | 1.26 (0.89 to 1.79) |

| Men | 1.42 (1.14 to 1.77) | 2.31 (1.65 to 3.24) | 2.14 (1.71 to 2.66) | 1.24 (0.82 to 1.87) | 2.38 (0.89 to 6.33) | 1.15 (0.89 to 1.49) | 1.58 (1.24 to 2.02) |

| Model 2¶ | |||||||

| Women | 2.25 (1.46 to 3.45) | 3.16 (1.99 to 5.03) | 2.01 (1.26 to 3.21) | 2.07 (1.23 to 3.48) | 1.77 (1.10 to 2.85) | 1.45 (1.03 to 2.04) | 1.25 (0.88 to 1.78) |

| Men | 1.21 (0.96 to 1.51) | 2.03 (1.44 to 2.86) | 1.25 (0.90 to 1.73) | 1.17 (0.78 to 1.76) | 1.98 (0.74 to 5.29) | 1.12 (0.87 to 1.45) | 1.62 (1.27 to 2.07) |

| Model 3** | |||||||

| Women | 2.02 (1.31 to 3.13) | 2.68 (1.66 to 4.34) | 1.77 (1.10 to 2.84) | 1.73 (1.02 to 2.92) | 1.64 (1.01 to 2.67) | 1.36 (0.96 to 1.93) | 1.13 (0.79 to 1.62) |

| Men | 1.13 (0.89 to 1.43) | 1.78 (1.22 to 2.58) | 1.09 (0.77 to 1.52) | 0.94 (0.61 to 1.44) | 2.00 (0.74 to 5.39) | 1.08 (0.83 to 1.40) | 1.52 (1.18 to 1.96) |

| Model 4††, ‡‡ | |||||||

| Women | 1.52 (0.98 to 2.37) | 1.66 (1.01 to 2.75) | 1.66 (1.02 to 2.69) | 1.67 (0.97 to 2.88) | 1.69 (1.02 to 2.78) | 1.20 (0.85 to 1.69) | 1.02 (0.72 to 1.46) |

| Men | 1.03 (0.81 to 1.31) | 1.48 (1.00 to 2.18) | 1.01 (0.72 to 1.42) | 0.91 (0.59 to 1.40) | 1.69 (0.62 to 4.61) | 1.06 (0.82 to 1.38) | 1.46 (1.13 to 1.87) |

*ORs and 95% CIs derived from three-level mixed effects logistic regression models.

†Data from five population-based studies: the Cardiovascular Disease, Living and Ageing in Halle Study (CARLA), the Dortmund Health Study (DHS), the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study (HNR), the Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg (KORA) S4 Study and the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP), Germany, 1997–2006.

‡Men: n=4538, women: n=4333.

§Model 1: unadjusted.

¶Model 2: adjusted by age.

**Model 3: adjusted by age, social class, employment status, neighbourhood unemployment rate, marital status.

††Model 4: adjusted by age, social class, employment status, neighbourhood unemployment rate, marital status, body mass index, physical exercise, smoking status (only for men).

‡‡Sample size n=8732 due to 139 missing values on lifestyle factors.

Women residing in neighbourhoods with a medium level of unemployment showed significantly elevated odds of having T2DM (OR 1.45 (95% CI 1.03 to 2.04); model 2), which was dissolved when the model was adjusted by confounding variables. In contrast, men residing in neighbourhoods with a high level of unemployment showed a 52% (95% CI 1.18 to 1.96) higher odds of having T2DM than men in low unemployment neighbourhoods in the confounder-adjusted model 3. T2DM was no longer associated with marital status after adjustment for confounding variables in model 3 (living without vs living with a partner: OR 1.17 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.51) in women, OR 1.20 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.61) in men).

As part of mediation analysis, the associations of lifestyle variables and social class, employment status and neighbourhood unemployment rate as well as the association between T2DM and lifestyle variables were tested. T2DM was related to BMI and physical exercise in men and women, but to smoking only in men and to alcohol consumption not in both (not taken into further consideration). BMI, physical exercise and smoking were tested to be statistically significantly associated with social class, employment status and neighbourhood unemployment rate, with some exceptions: In women, physical exercise was not associated with employment status and smoking was not related to any social variable. Thereupon, the lifestyle variables were introduced into model 4 and the estimates of social class, employment status and neighbourhood unemployment rate evaluated in respect of reductions in the association with T2DM. In men and women, we observed reductions in the effects of individual social class, employment status and neighbourhood unemployment rate when introducing these lifestyle factors in the analysis. The association between social class and T2DM was strongly reduced, especially in women. This reduction was mainly driven by BMI in women (solely adjusted by BMI, higher vs lower social class OR 1.73 (95% CI 1.05 to 2.85)) and by physical exercise in men (solely adjusted by physical exercise, higher vs lower social class OR 1.59 (95% CI 1.09 to 2.32)), providing evidence that these lifestyle variables partly mediated the relationship between social class and T2DM.

Between-study and between-neighbourhood variations in the prevalence of T2DM were larger in women than in men. The prevalence of T2DM in men varied only between study regions (unadjusted model: MOR: 1.20; VA: 0.04; SE: 0.03; online supplementary table S5), which was fully explained statistically by age, social class, employment status, neighbourhood unemployment rate, marital status and lifestyle factors. T2DM prevalence in women showed a large variation across neighbourhoods (unadjusted model: MOR: 1.47; VA: 0.16; SE: 0.10) and study regions (unadjusted model: MOR: 1.31; VA: 0.07; SE: 0.06), which was not dissolved by the explanatory variables considered (between-neighbourhood variation: MOR: 1.32; VA: 0.08; SE: 0.09, between-study variation: MOR: 1.29; VA: 0.07; SE: 0.06; model 5, online supplementary table S5).

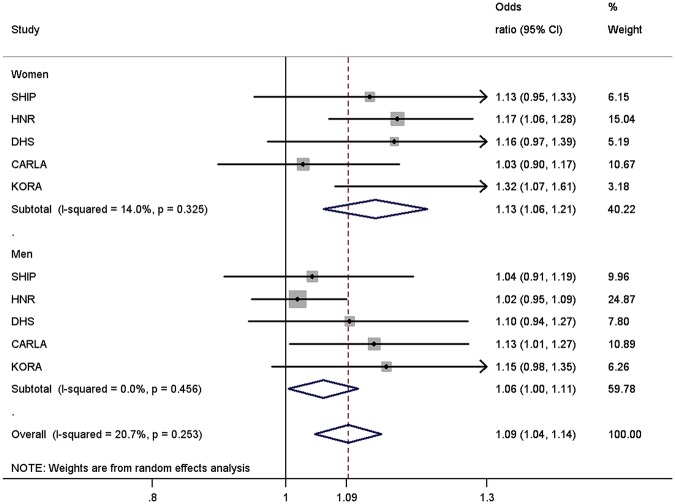

Regarding gender differences in health inequalities across regions, the effect estimates of the five studies were tested to be homogeneous (figure 1). Low social class was associated with higher odds of T2DM, adjusted for age, employment status, marital status and neighbourhood unemployment rate. In women, an increase of one point on the social class score (decrease in social class) was associated with an increase of 13% (pooled OR: 1.13 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.21); I2=14.0%; p=0.325) in the odds of having T2DM. This association was smaller in men (pooled OR: 1.06 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.11); I2=0.0%; p=0.456), although the differences between genders were not significant. This was observed in all studies, except CARLA.

Figure 1.

Meta-analysis of five logistic regressions of type 2 diabetes mellitus for the social class score (range: 2–14 points) in women and men.a–d aORs and 95% CI derived from study-stratified two-level mixed effects logistic regression models. bAdjusted for age, employment status, marital status and neighbourhood unemployment rate. cData from five population-based studies: the cardiovascular disease, living and ageing in Halle Study (CARLA), the Dortmund Health Study (DHS), the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study (HNR), the Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg (KORA) S4 Study, and the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP), Germany, 1997–2006. dHeterogeneity tested via the Q statistic and I² index.

Discussion

This study assessed gender differences in the association of individual social class, employment status and neighbourhood unemployment rate with prevalent T2DM, using data from five regional population-based studies in Germany. Women and men belonging to the lower social class had a higher prevalence of T2DM. We found that the gradient in the prevalence of T2DM across social classes was clearly stronger in women than in men. This pattern was consistent across all regions but CARLA and mainly in line with results of prior studies presenting only associations in women,7–9 or in women and men, but more pronounced in women.5 6

In our study, individual employment status was only associated with T2DM in women. Being unemployed, retired or a housewife yielded higher odds of T2DM. However, since we were not able to consider occupational position in our analyses, the interpretation of these findings is limited. In the literature, two contrasting theories are discussed for the effects of paid employment on women's health. Employment can have a health promoting function due to role accumulation in contrast to the monotony, isolation, low-social status and self-esteem of housewives. A health damaging effect could arise due to role strains, for example, stress due to multiple roles, and heavy job demands.35 36

Men residing in neighbourhoods with a high level of unemployment rate were more likely to have T2DM than men in better-off neighbourhoods. These effects remained even after adjustment for confounding and mediator variables, whereas associations between neighbourhood unemployment rate and T2DM in women were dissolved by the introduction of confounding variables. These deviating effects of neighbourhood unemployment rate between men and women may be explained by the fact that men were more often engaged in employment and hence depended more on the regional labour market and its employment opportunities than women. The potential underlying mechanisms in the relationship between neighbourhood unemployment rate and T2DM include neighbourhood resources such as the availability of grocery stores offering healthy food and recreational facilities,15 the adoption and maintenance of risky health behaviour and psychosocial factors such as chronic stress.13 37

Between-study and between-neighbourhood variations in the prevalence of T2DM were larger in women than in men. We found that individual social class, employment status and neighbourhood unemployment rate played important roles in explaining statistically regional differences in the prevalence of T2DM in men. A large fraction of the detected variation in the prevalence of T2DM on the level of neighbourhoods and regions remained statistically unexplained in women, suggesting that there were characteristics on the individual, neighbourhood and regional levels that determined the presence of T2DM and were not considered in our analysis. Previous work on regional variation in self-rated health and BMI also found a larger regional variation in women.19 38 39

The gender-specific pattern in the association between social class and the prevalence of T2DM needs to be further explored, since the pathways are still unknown.6 Macintyre and Hunt40 noted that socioeconomic determinants vary in their meaning for men and women, since both genders are socialised in different ways with diverging social roles and coping strategies against stress; they hold different occupational positions in the labour market and have dissimilar access to material and psychosocial resources. In our study, overall women were less likely to be in the higher social class and were less often employed.

To gain more insight into mechanisms of social inequalities on health, the analysis of population subgroups is essential, since one limitation of the existing literature is the assumption that mechanisms operate identically in different population groups.19 This work adds knowledge to the research on the interaction of gender, social determinants and health. So far, only a few studies have examined this interaction with regard to T2DM and, to our knowledge, no study has considered neighbourhood unemployment rate in regard to that until now. Data sources providing representative population-based data on the prevalence of T2DM with a linkage to small areas and regions are still rare.

Some limitations of this work should be acknowledged. We analysed cross-sectional data with limited causal conclusions. We could not use occupation as an indicator of social class in our analysis since the assessment was not comparable between studies. The prevalence of T2DM was based on a self-reported T2DM physician's diagnosis only, which could not be validated. Therefore, undetected T2DM could be a source of bias. However, Okura et al41 found a high accuracy between self-reports and medical records for diabetes and other chronic diseases. Recently, Jackson et al42 concluded that self-reported diabetes is a valid outcome for observational studies with an accuracy of 91.8% of self-reported prevalent diabetes validated by medical records based on the Women's Health Initiative. Another potential limitation is the selection by response (response proportions: 56–69%), which might have affected our results. The exclusion of participants from the initial sample due to missing information on individual characteristics (mainly due to missing information on net household income) could have led to an underestimation of the social gradient in T2DM, because these participants were on average older, more often women, out of employment and with a lower educational status. However, a sensitivity analysis showed similar results applying education as a measure of social class.

We used administrative definitions for neighbourhoods. Hence, neighbourhoods in our study may not capture the immediate neighbourhood of residence of our study participants. This could lead to exposure misclassification and underestimation of neighbourhood effects.43 The applied administrative definition of neighbourhoods differed between studies and these neighbourhoods were diverse according to their area and population size. Another challenge in the research of neighbourhood impact on health is the residential selection. Individuals may be selected into neighbourhoods due to individual characteristics, such as residents of poor areas being unable to afford moving to better-off neighbourhoods.44 45 Finally, we had no information on the residential history of the study participants, which could result in an underestimation of neighbourhood effects on health.46

In conclusion, our study identified different relationships of individual social class, employment status and neighbourhood unemployment rate with the prevalence of T2DM for women and men. In both men and women, the prevalence of T2DM was inversely related to social class. This social gradient was stronger in women. Regional variance in T2DM prevalence was larger in women than in men. Although the major proportion of the variance in T2DM prevalence remained statistically unexplained in women, the regional variance in men was low and completely explained by the variables considered.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: GM, KB (DHS), SH, KHG (CARLA), SM, NP (HNR), SS, HV (SHIP), WM and CM (KORA) researched data. GM developed the study conception, performed the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. KB contributed to the study conception, statistical analyses and data interpretation. WR and TT contributed to the pooling of data. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the interpretation of the results.

Funding: This work was supported by the Competence Network Diabetes mellitus of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, grant 01GI0814). The Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP) is part of the Community Medicine Research net (http://www.community-medicine.de) at the University of Greifswald, Germany. Funding was provided by grants from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, grant 01ZZ0403); the Ministry for Education, Research, and Cultural Affairs; and the Ministry for Social Affairs of the Federal State of Mecklenburg–West Pomerania. The Cardiovascular Disease, Living and Ageing in Halle Study (CARLA) was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft as part of the Collaborative Research Center 598 “Heart failure in the elderly—cellular mechanisms and therapy” at the Medical Faculty of the Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, by a grant of the Wilhelm-Roux Programme of the Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg; by the Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs of Saxony-Anhalt, and by the Federal Employment Office. The collection of sociodemographic and clinical data in the Dortmund Health Study (DHS) was supported by the German Migraine and Headache Society (DMKG) and by unrestricted grants of equal share from Astra Zeneca, Berlin Chemie, Boots Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, McNeil Pharma (former Woelm Pharma), MSD Sharp and Dohme and Pfizer to the University of Muenster. We thank the Heinz Nixdorf Foundation (Germany) for the generous support of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study (HNR). The study is also supported by the German Ministry of Education and Science. We acknowledge the support of the Sarstedt AG & Co. concerning laboratory equipment. We thank the investigative group and the study staff of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. The KORA research platform (KORA, Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg) was initiated and financed by the Helmholtz Zentrum München—German Research Center for Environmental Health, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and by the State of Bavaria. The KORA Diabetes Study was partly funded by a German Research Foundation project grant to W.R. from the German Diabetes Center. The German Diabetes Center is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health, and the Ministry of School, Science and Research of the State of North-Rhine-Westphalia.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study protocols were approved by the local ethics committees.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Thurston RC, Kubzansky LD, Kawachi I, et al. Is the association between socioeconomic position and coronary heart disease stronger in women than in men? Am J Epidemiol 2005;162:57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denton M, Prus S, Walters V. Gender differences in health: a Canadian study of the psychosocial, structural and behavioural determinants of health. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:2585–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacIntyre S, Hunt K. Socio-economic position, gender and health: how do they interact? J Health Psychol 1997;2:315–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agardh E, Allebeck P, Hallqvist J, et al. Type 2 diabetes incidence and socio-economic position: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:804–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka T, Gjonça E, Gulliford MC. Income, wealth and risk of diabetes among older adults: cohort study using the English longitudinal study of ageing. Eur J Public Health 2011:310–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robbins J, Vaccarino V, Zhang H, et al. Socioeconomic status and type 2 diabetes in African American and non-Hispanic white women and men: evidence from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Public Health 2001;91:76–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang M, Chen Y, Krewski D. Gender-related differences in the association between socioeconomic status and self-reported diabetes. Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:381–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross NA, Gilmour H, Dasgupta K. 14-year diabetes incidence: the role of socio-economic status. Health Rep Stat Can 2010;21:19–28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imkampe AK, Gulliford MC. Increasing socio-economic inequality in type 2 diabetes prevalence—repeated cross-sectional surveys in England 1994–2006. Eur J Public Health 2011;21:484–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith BT, Lynch JW, Fox CS, et al. Life-course socioeconomic position and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:438–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumari M, Head J, Marmot M. Prospective study of social and other risk factors for incidence of type 2 diabetes in the Whitehall II study. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1873–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maty SC, Everson-Rose SA, Haan MN, et al. Education, income, occupation, and the 34-year incidence (1965–99) of type 2 diabetes in the Alameda County Study. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:1274–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diez-Roux AV, Jacobs DR, Kiefe CI. Neighborhood characteristics and components of the insulin resistance syndrome in young adults. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1976–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Auchincloss AH, Diez Roux AV, Brown DG, et al. Association of insulin resistance with distance to wealthy areas. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:389–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Auchincloss AH, Diez Roux AV, Brown DG, et al. Neighborhood resources for physical activity and healthy foods and their association with insulin resistance. Epidemiology 2008;19:146–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schipf S, Werner A, Tamayo T, et al. Regional differences in the prevalence of known Type 2 diabetes mellitus in 45–74 years old individuals: results from six population-based studies in Germany (DIAB-CORE Consortium). Diabet Med 2012;29:88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müller G, Kluttig A, Greiser KH, et al. Regional and Neighborhood Disparities in the Odds of Type 2 Diabetes: Results From 5 Population-Based Studies in Germany (DIAB-CORE Consortium). Am J Epidemiol 2013. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws466 [published Online First: Epub Date]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maier W, Holle R, Hunger M, et al. The impact of regional deprivation and individual socio-economic status on the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Germany. A pooled analysis of five population-based studies. Diabet Med 2013;30:e78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stafford M, Cummins S, Macintyre S, et al. Gender differences in the associations between health and neighbourhood environment. Soc Sci Med 2005;60:1681–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greiser K, Kluttig A, Schumann B, et al. Cardiovascular disease, risk factors and heart rate variability in the elderly general population: design and objectives of the CARdiovascular disease, Living and Ageing in Halle (CARLA) study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2005;5:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Völzke H, Alte D, Schmidt CO, et al. Cohort profile: the study of health in Pomerania. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:294–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dragano N, Hoffmann B, Stang A, et al. Subclinical coronary atherosclerosis and neighbourhood deprivation in an Urban region. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rathmann W, Haastert B, Icks A, et al. High prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in Southern Germany: target populations for efficient screening. The KORA survey 2000. Diabetologia 2003;46:182–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vennemann M, Hummel T, Berger K. The association between smoking and smell and taste impairment in the general population. J Neurol 2008;255:1121–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schunk M, Reitmeir P, Schipf S, et al. Health-related quality of life in subjects with and without type 2 diabetes: pooled analysis of five population-based surveys in Germany. Diabet Med 2012;29:646–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breckenkamp J, Mielck A, Razum O. Health inequalities in Germany: do regional-level variables explain differentials in cardiovascular risk? BMC Public Health 2007;7:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dragano N, Bobak M, Wege N, et al. Neighbourhood socioeconomic status and cardiovascular risk factors: a multilevel analysis of nine cities in the Czech Republic and Germany. BMC Public Health 2007;7:255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cummins S, Stafford M, Macintyre S, et al. Neighbourhood environment and its association with self rated health: evidence from Scotland and England. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:207–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Lenthe FJ, Borrell LN, Costa G, et al. Neighbourhood unemployment and all cause mortality: a comparison of six countries. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:231–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell DA, Radford JM, Burton P. Unemployment rates: an alternative to the Jarman index? BMJ 1991;303:750–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larsen K, Merlo J. Appropriate assessment of neighborhood effects on individual health: integrating random and fixed effects in multilevel logistic regression. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:81–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merlo J, Chaix B, Ohlsson H, et al. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:290–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sterne JAC, Bradburn MJ, Egger M. Meta-analysis in Stata. In: Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG, eds. Systematic Reviews in Health Care. Meta-analysis in context. London: BMJ, 2008:347–69. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huedo-Medina T, Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, et al. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Center for Health, Intervention, and Prevention Documents 2006;Paper 19 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Arber S, Gilbert GN, Dale A. Paid employment and women's health: a benefit or a source of role strain? Sociol Health Ill 1985;7:375–400 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Repetti RL, Matthews KA, Waldron I. Employment and women's health: effects of paid employment on women's mental and physical health. Am Psychol 1989;44:1394–401 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krishnan S, Cozier YC, Rosenberg L, et al. Socioeconomic status and incidence of type 2 diabetes: results from the black women's health study. Am J Epidemiol 2010;171:564–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King T, Kavanagh AM, Jolley D, et al. Weight and place: a multilevel cross-sectional survey of area-level social disadvantage and overweight//obesity in Australia. Int J Obes 2005;30:281–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robert SA, Reither EN. A multilevel analysis of race, community disadvantage, and body mass index among adults in the US. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:2421–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacIntyre S, Hunt K. Socio-economic position, gender and health. J Health Psychol 1997;2:315–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okura Y, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, et al. Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:1096–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson JM, DeFor TA, Crain AL, et al. Self-reported diabetes is a valid outcome in pragmatic clinical trials and observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:349–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Introduction. In: Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Neighborhoods and health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003:1–19 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diez Roux AV. Estimating neighborhood health effects: the challenges of causal inference in a complex world. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:1953–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sampson RJ. Neighborhood-level context and health: lessons from sociology. In: Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Neighborhoods and health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003:132–46 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yen IH, Kaplan GA. Neighborhood social environment and risk of death: multilevel evidence from the Alameda County Study. Am J Epidemiol 1999;149:898–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.