Abstract

Much of the research used to support the ratification of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) was conducted in high-income countries or in highly controlled environments. Therefore, for the global tobacco control community to make informed decisions that will continue to effectively inform policy implementation, it is critical that the tobacco control community, policy makers, and funders have updated information on the state of the science as it pertains to provisions of the FCTC. Following the National Cancer Institute’s process model used in identifying the research needs of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s relatively new tobacco law, a core team of scientists from the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco identified and commissioned internationally recognized scientific experts on the topics covered within the FCTC. These experts analyzed the relevant sections of the FCTC and identified critical gaps in research that is needed to inform policy and practice requirements of the FCTC. This paper summarizes the process and the common themes from the experts’ recommendations about the research and related infrastructural needs. Research priorities in common across Articles include improving surveillance, fostering research communication/collaboration across organizations and across countries, and tracking tobacco industry activities. In addition, expanding research relevant to low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), was also identified as a priority, including identification of what existing research findings are transferable, what new country-specific data are needed, and the infrastructure needed to implement and disseminate research so as to inform policy in LMIC.

INTRODUCTION

In 2005, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) was ratified by enough countries that it became the first global public health treaty in history. This treaty is based on a solid corpus of research that provides a scientific foundation and rationale for a variety of tobacco control practices and policies that will reduce tobacco use once implemented, including increasing the cost of tobacco, reducing exposure to second-hand smoke, and assuring that all smokers receive effective treatment. As on May 2012, 175 nations have ratified the treaty, and considerable global effort is in place to implement articles in the treaty.

However, as countries strive to implement the provisions of the treaty, it is also clear that the research conducted to date is clearly not enough to assure optimal implementation given the differences between countries and regions due to differences in the resources available, extent of the tobacco burden, the influence of the tobacco industries, and competing needs. For example, because much of the research used to support the ratification of the FCTC was conducted in high-income countries or in highly controlled environments, it is not clear what unique country-specific data are needed to assure optimal implementation of specific Articles of the treaty, or whether “real world” approaches will work, as well as more controlled research outcomes. Thus, there is a need to (a) determine which research findings can be directly implemented in different environments, such as low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Reddy et al., 2010), (b) conduct research to determine how to disseminate and implement research findings in different environments (Glasgow & Chambers, 2012; Reddy et. al., 2010), and (c) identify what new research is needed given unique country needs, changing tobacco company threats, or because of the evolving tobacco control environment.

Moreover, successful implementation of the Treaty provisions will require ongoing research and monitoring activity as environments change and the tobacco industry adapts to the changing regulatory environment. As demonstrated in Table 1 (WHO, 2005), Article 20 of the FCTC provides specific language regarding the need for research, but this Article provides no strategic plan for prioritizing new research required by the FCTC or the infrastructures needed to implement and disseminate this research. This is essential given the complexity of tobacco control in general but also because of the need to consider the complex systems that are involved and the need to assure that appropriate organizational (including governmental) infrastructures can adapt or be created to facilitate systems change (Leischow et al., 2008; Leischow et al., 2010) and to optimize research to practice or policy (Harris, Provan, Johnson, & Leischow, 2012). In order for the global tobacco control community to make informed decisions that will inform policy implementation and future public health policy, it is critical that the tobacco control community, policy makers, and funders have updated information on the state of the science as it pertains to the provisions of the FCTC.

Table 1.

FCTC Article 20: Research, Surveillance and Exchange of Information

| WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control |

|---|

| Part VII: Scientific and Technical Cooperation and Communication of Information |

| Article 20: Research, surveillance and exchange of information |

|

Source: WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (2003). Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42811/1/9241591013.pdf (date last accessed November 30, 2012). Reproduced with permission from the World Health Organization.

Given the lack of clarity regarding the research needs of the FCTC, the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) funded the Global Network of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco to develop and implement an initiative designed to begin that process.

PURPOSE AND NATURE OF THE INITIATIVE

The purpose of this project was to undertake an assessment of the FCTC in order to identify key priority research needs, including research areas and skills, collaboration, dissemination and implementation, and to develop multiple documents that summarize those findings. Moreover, the proposed project had two specific components: (a) identify and summarize the research that currently exists and (b) propose future research to fill gaps. The proposed outcome of this initiative is a series of papers made available to the global tobacco control community, particularly funders or those who impact funding, that would help to inform decision making on research priorities that have the potential to improve the rigor and effectiveness of FCTC implementation around the globe.

Toward that end, a core scientific team was selected to identify the research requirements and needs within the FCTC, and this core team included multidisciplinary (e.g., tobacco chemistry, marketing, treatment, etc.) SRNT scientists around the world. This team was comprised of the following SRNT members: Olalekan Ayo-Yusuf, Cathy Backinger, Ron Borland, Thomas Glynn, Tai-Hing Lam, Scott Leischow, Ann McNeill, and Mitch Zeller. Of this group, Ayo-Yusuf, Backinger, and Leischow led the initiative with assistance from the SRNT Executive Director. Following the NCI model of successful effort with respect to identifying the research needs of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s relatively new tobacco law (Leischow et al., 2012), the core team then identified internationally recognized scientific experts on topics covered within the FCTC Articles. Those experts (who, in some cases, added additional authors) were commissioned to analyze the relevant sections of the FCTC in order to (a) identify existing research that could inform the law and its implementation, (b) identify critical gaps in research that is needed to inform policy and practice requirements in the law, and (c) prepare a paper describing the outcomes of the analyses and recommendation about research needs to be for each identified area to be published.

More specifically, each paper includes the following:

1. A description of what the FCTC says about the given topic (e.g., limits on product marketing, warnings and product labeling, product content disclosure and regulation, pricing and tax policy, protection of people from second-hand smoke);

2. A brief history of regulation related to the topic (e.g., regulatory efforts to limit product marketing—who, what, when, where, etc.);

3. A description of what is known in the global scientific literature about the effectiveness of different regulatory measures on the topic;

4. A list of what is not known about the topic, important information, and/or knowledge parties to FCTC will need to obtain in order to help it provide informed oversight/regulation on the assigned topic (e.g., product marketing).

5. An analysis of research required to fill knowledge gaps about the topic, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Authors were also asked to identify, in their professional opinion, the topmost 5–6 research needs in no order of priority as priority may be different for different countries.

Given the parameters above for reviewing the Articles, the core planning committee also elected to combine some Articles that are based on similar science or are conceptually similar. As a result, the papers that were commissioned and which appear in this themed issue of Nicotine & Tobacco Research are as follows:

1. Articles 6 and 15—Price and tax measures, and illicit trade (lead author: Corne van Walbeek)

2. Article 8—Protection from exposure to tobacco smoke (lead author: Joaquin Barnoya)

3. Articles 9 and 10—Tobacco content and disclosure (lead author: Nigel Gray)

4. Articles 11 and 12—Health warnings labeling combined with education, mass media, packaging (lead author: David Hammond)

5. Articles 13 and 16—Advertising, marketing, social media, promotion, and sales to minors (lead author: Rebekah Nagler)

6. Article 14—Tobacco treatment (lead author: Hayden McRobbie)

7. Articles 20, 21, and 22—Surveillance/epidemiology and information exchange (infrastructure and capacity-building needs; lead author: Gary Giovino)

The core scientific team received outlines and drafts of the papers from each of the lead scientists, and after reviewing the papers, returned them to the authors with comments. In addition, the recommendations from the papers were presented at two different international public forums, which provided additional opportunities to seek guidance from the scientific community. First, an SRNT preconference symposium was convened at the September 2011 SRNT-Europe conference in Turkey where each of the papers was presented publicly and comments were provided to the authors and core team for potential inclusion in the articles to be published. In addition, a symposium at the World Conference on Tobacco or Health in March 2012 created an opportunity for the broader tobacco control community to provide input. This process thus allowed considerable public input from the scientific and tobacco control community during the development stages prior to submission to the peer-review process for consideration for journal publication.

FCTC RECOMMENDATIONS: COMMON THEMES AND STRUCTURAL NEEDS

Each of the papers provide a set of rich review on the state of the science pertaining to the FCTC Articles, along with both a list of research needs and a “short list” of top research recommendations. When the top recommendations are compared across each of the papers, several common research needs and themes emerge.

Improved Surveillance

Multiple Articles (e.g., Article 20) call for effective and comprehensive surveillance systems, and multiple recommendations were made to emphasize that point. Giovino, Kulak, Kalsbeek, and Leischow (2012) identified improvements in sampling strategies so that targeted interventions and efforts could be developed, depending on country needs, and to “assess possible under-reporting of tobacco use among certain demographic groups in some countries.” Gray and Borland (2012) indicated the need for “appropriate monitoring and evaluation mechanism to assess the impacts of regulations when they occur,” as well as “surveillance of the market, including the illicit sector.” Similarly, van Walbeek et al. (2012) recommended increased “monitoring of tobacco consumption, prices, and taxes.” However, as Nagler and Viswanath (2012) note, “infrastructure to monitor people’s exposure to tobacco-related marketing, media and messages, and effects of such exposure on tobacco consumption is urgently needed.” Current efforts, such as the International Tobacco Control initiative provide important surveillance data, but it needs to be expanded to dramatically.

Fostering Communication/Collaboration

Giovino et al. (2012) discussed the research needs of Articles 20–22, which call for increased communication and collaboration across those organizations and countries striving to foster implementation of the FCTC Articles. More specifically, they call for research on “network/relationship factors that impact diffusion of knowledge and decision making on the implementation of the FCTC.” Similarly, van Walbeek et al. (2012) recommend engaging “local researchers, academic institutions and/or government agencies in collaborative research with content experts,” with a specific focus on fostering “multidisciplinary” research that encouraged collaboration between economists and policy experts.

As discussed in the NCI Monograph “Greater than the Sum” (NCI, 2007), assessing, fostering, and optimizing collaborative networks are fundamental to making effective systemic changes. Thus far, the coordination and communication to support the most rapid and thorough implementation of the FCTC Articles has been impressive given the minimal amount of financial support, but needs to be expanded given the extent and complexity of implementing Articles across widely varied circumstances. The advocacy and direction-setting initiatives of the Framework Convention Alliance (FCA) and the WHO Conference of the Parties (COP) process are essential, but funds to support travel by those from low-income countries to participate in the WHO COP process have been insufficient. The recommendation by McRobbie, Raw, and Chan (2012) to support “collaboration that includes international funding” reflects the reality that funding is needed to support research on ways to optimize communication and collaboration that can optimize FCTC policy implementation.

Tobacco Industry Tracking

Although this research priority could rightly be placed under the surveillance section, we believe that tracking tobacco industry efforts warrants its own section given the recommendations under Article 5—and because unlike almost all other public health threats, there are active human directed efforts designed to undermine the public health community. In effect, tracking tobacco industry efforts goes beyond “surveillance’ and into the realm of “intelligence” because discovering and collecting data on industry efforts does not necessarily lead to obvious interpretation or action. Thus, Giovino et al. (2012) recommend strengthening measures to assess tobacco industry activities and even “study networks of tobacco companies and their partners as they promote tobacco use and interfere with implementation of the FCTC.” Barnoya and Navas-Acien (2012) likewise encourage “research on industry sponsored hospitality groups, smokers’ rights organizations, ineffective ventilation systems and lobbying,” whereas Nagler and Viswanath (2012) recognize the complexity of tracking the tobacco industry and their related partners by calling for increased “scientific capacity within the countries to monitor tobacco industry activities and document any violation of tobacco control laws.”

Dissemination and Implementation Research

Much has been written about the increasing recognition that controlled trials do not necessarily lead of effective real-world practices, and that a new science of dissemination is needed to assure that research has the best potential to have the greatest population impact in the shortest period of time (Glasgow and Chambers, 2012). With respect to the FCTC, Nagler and Viswanath (2012) framed the challenges in the following way: “What is lacking is research on how to successfully translate this knowledge in different national contexts to successfully implement FCTC provisions. Knowledge translation research and knowledge exchange efforts will go far in effective implementation of FCTC.”

For example, one of the top treatment research priorities identified by McRobbie et al. (2012) is to “assist healthcare workers provide better help to smokers (e.g., through implementation of guidelines and training)” and to “enhance population-based tobacco dependence treatment interventions.” Barnoya and Navas-Acien (2012) encourage research and evaluation that allows for one to “compare different country experiences (e.g., Uruguay, US, China)” and that “dissemination and policy implications of research results should be taken into consideration early in the research process. Finally, as Nagler and Viswanath (2012) conclude, “research is needed in translating the knowledge of successful policy and behavioral interventions to change tobacco control policies and practice.”

Focus Attention on LMIC Needs

The World Health Organization led an early and less ambitious effort to identify the research needs of the FCTC (Reddy et al., 2010), and that report provides important perspectives regarding the research challenges and opportunities. One important theme in that report was the need to focus on LMICs because tobacco-caused death rates “are increasing and will continue to increase, with a growing proportion of those deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries.” Similarly, papers in this themed issue recognized the unique research needs of LMICs. Indeed, research that is specific to the unique needs and infrastructures of LMICs has the greatest potential to inform policy in those countries. There is, however, the need to also promote demand for research (i.e., evidence pull) in LMICs through the use of knowledge brokers such as the FCA and the media who can facilitate continuous dialogue between researchers and policy makers.

In emphasizing the need for the right context, Hammond, Wakefield, Durkin, and Brennan (2012) point out that research is needed to “understand potential differences among population subgroups and across different cultures” and to “examine the interplay between the extent of mass media campaign exposure, the type of mass media messages, and the behavioral outcomes in population-based studies.” Put another way, “different audiences need data provided in different ways” (Barnoya and Navas-Acien, 2012).

Fundamental to addressing the unique needs of LMICs is the lack of resources in those countries to collect new data, to analyze, and to interpret it in the context of their environment, and then to use that information to implement practices and policies. Thus, although Giovino et al. (2012) indicated the need to “assess possible under-reporting of tobacco use among certain demographic groups in some countries” that will be difficult to accomplish in many cases because of “a need for development of research capacity and collaboration that includes international funding” (McRobbie et al., 2012).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

The papers that appear in this themed issue of Nicotine & Tobacco Research endeavor to provide both a look back at the state of the science that led to the FCTC and which supports implementation of specific policies and practices. But they also provide specific research recommendations that will help to assure that science continues to inform policy and practice. The recommendations are consistent with those of the WHO (Reddy et al., 2010), but provide additional background and rationale, as well as greater specificity regarding research needs. In addition, there was greater vetting of the recommendations via presentations at major international tobacco control conferences.

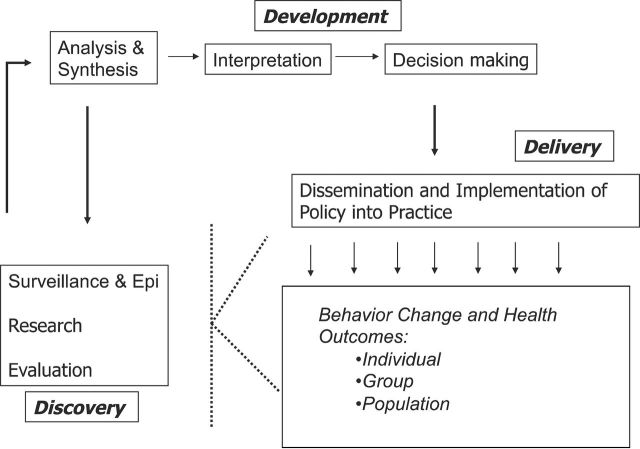

Collectively, the papers recognize the primacy of science, yet also clearly recognize that “discovery” does not necessarily lead to the “development” of effective decisions. This “discovery, development, and delivery” model can be characterized as a systems model built on the premise that active efforts are needed to foster movement from one part of the model (e.g., research) to another (e.g., development) (Figure 1). Moving from data collection processes that are inherent in “discovery” to interpretation and decision-making processes that are inherent in “development” and then to implementation processes that are inherent in “delivery” requires national and transnational infrastructure, networks, and partnership (e.g., FCA, etc.) to foster communication and collaboration toward our common goal of reducing tobacco caused morbidity and mortality to the extent feasible. The papers in this themed issue are an exercise in “development,” and in particular the essential need to synthesize existing knowledge and provide interpretation that can guide decision making on research to achieve the greatest tobacco control outcomes.

Figure 1.

Discovery, development and delivery model.

Although Figure 1 represents an optimal flow from discovery to development to delivery, the process is often not linear. For example, it is clear that in LMICs the process may need to be different. More specifically, it is essential to determine whether existing data can be effectively disseminated and implemented in LMICs or whether new data need to be collected and analyzed in the unique contexts of LMICs so that those data are most useful in those environments. In addition, given the lack of “discovery” and key components of the “development” infrastructure (e.g., synthesis) in LMICs, perhaps specific transnational “collaboratives” could be established to make recommendations on which data are directly applicable to specific countries and which data or syntheses need to be generated to meet the specific needs of a particular country or region. Moreover, because policy makers in some LMICs have limited understanding regarding the role of science in public health practice and policy (Carden, 2009), there might be a need to educate policy makers on making use of scientific information for input into policy decision making while encouraging increased resource allocation for research.

In summary, the papers in this themed issue of Nicotine & Tobacco Research provide the most thorough analysis to date on the state of the science that served as a foundation for the FCTC and also provides important new directions and priorities for research that can help to improve and speed the implementation of global tobacco control policies and practices. Most importantly, they collectively highlight and reinforce the premise that tobacco control is not static or linear and represent a complex dynamic system with changing needs as a result of differential implementation of policies, variations in tobacco industry influence, efficacy of civil society in expanding tobacco control as a social norm, global economic factors, etc. Given that complexity, new research is needed to assure that we not just maintain momentum in implementation of the FCTC but also to make the necessary data-driven shifts in priority setting that will continue to make the FCTC an effective public health tool.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper represents the views of its authors and not necessarily those of the organizations where the authors are employed. The National Cancer Institute provided support for this project.

REFERENCES

- Barnoya J., Navas-Acien A. (2012). Protecting the world from secondhand tobacco smoke exposure: Where do we stand and where do we go from here? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 10.1093/ntr/nts200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carden F. (2009). Knowledge to policy. Retrieved from http://idl-bnc.idrc.ca/dspace/bitstream/10625/37706/1/127931.pdf

- Giovino G. A., Kulak J. A., Kalsbeek W. D., Leischow S. J. (2012). Research priorities for FCTC Articles 20, 21, and 22: Surveillance/evaluation and information exchange. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 10.1093/ntr/nts336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R. E., Chambers D. (2012). Developing robust, sustainable, implementation systems using rigorous, rapid and relevant science. Clinical and Translational Science. 5, 48–55. 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00383.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray N., Borland R. (2012). Research required for the effective implementation of the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control, Articles 9 and 10. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 10.1093/ntr/nts175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond D., Wakefield M., Durkin S., Brennan E. (2012). Tobacco packaging and mass media campaigns: Research needs for Articles 11 and 12 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 10.1093/ntr/nts202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. K., Provan K. G., Johnson K. J., Leischow S. J. (2012). Drawbacks and benefits associated with inter- organizational collaboration along the discovery–development– delivery continuum: A cancer research network case study. Implementation Science, 7, 69. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leischow S. J., Best A., Trochim W. M., Clark P. I., Gallagher R. S., Marcus S. E., Matthews E. (2008). Systems thinking to improve the public’s health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 35,S196–S203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leischow S. J., Luke D. A., Mueller N., Harris J. K., Ponder P., Marcus S., Clark P. I. (2010). Mapping U.S. government tobacco control leadership: Networked for success? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 12,888–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRobbie H., Raw M., Chan S. (2012). Research priorities for Article 14—Demand reduction measures concerning tobacco dependence and cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 10.1093/ntr/nts244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagler R. H., Viswanath K. (2012). Implementation and research priorities for FCTC Articles 13 & 16: Tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship and sale to and by minors. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 10.1093/ntr/nts331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute (NCI) (2007). Greater than the sum: Systems thinking in tobacco control (Tobacco Control Monograph No. 18). Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; [Google Scholar]

- Reddy K. S., Chaloupka F. J., Arora M., Panda R., Mathu M. R., Samet J., Bettcher D. (2010). Research priorities: Tobacco control. In A prioritized research agenda for prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases (1–18). Geneva: WHO; [Google Scholar]

- van Walbeek C., Blecher E., Gilmore A., Ross H. (2012). Price and tax measures and illicit trade in the FCTC: What we know and what research is required. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 10.1093/ntr/nts170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2005). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/fctc/en/

- WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (2003) Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42811/1/9241591013.pdf (date last accessed 30.11.2012).