Abstract

Objective

The early application of cognitive rehabilitation may afford long-term functional benefits to patients with schizophrenia. This study examined the two-year effects of an integrated neurocognitive and social-cognitive rehabilitation program, cognitive enhancement therapy (CET), on cognitive and functional outcomes in early course schizophrenia.

Method

Early course outpatients (mean illness duration = 3.19±2.24 years) with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were randomly assigned to CET (n = 31) or enriched supportive therapy (EST) (n = 27), an illness management intervention utilizing psychoeducation and applied coping strategies, and treated for 2 years. Multivariate composite indexes of cognitive, social adjustment, and symptomatology domains were derived from assessment batteries administered annually by computer-based tests and raters not blind to treatment assignment.

Results

Of the 58 patients randomized and treated, 49 and 46 completed 1 and 2 years of treatment, respectively. Intent to treat analyses showed significant differential effects favoring CET on social cognition, cognitive style, social adjustment, and symptomatology composites during the first year of treatment. After two years, moderate effects (d = .46) were observed favoring CET at enhancing neurocognitive function. Strong differential effects (d > 1.00) on social cognition, cognitive style, and social adjustment composites remained at year 2, and also extended to measures of symptomatology, particularly negative symptoms.

Conclusions

CET appears to be an effective approach to the remediation of cognitive deficits in early schizophrenia that may help reduce disability among this population. The remediation of such deficits should be an integral component of early intervention programs treating psychiatrically stable schizophrenia outpatients.

Schizophrenia is a chronic and disabling mental disorder that is characterized by related deficits in cognition, functioning, and adjustment. The significant personal and societal costs of the disorder (1), its frequent deteriorating course (2, 3), and the consistent negative prognosis associated with untreated illness (4), all highlight the importance of early applications of evidence-based interventions to reduce long-term morbidity (5). Cognitive impairments, in particular, are promising targets for early intervention due to their early emergence (6), persistence (7), and contribution to functional outcome (8). Unfortunately, few successful efforts have been directed toward the early treatment of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia.

Early course pharmacological studies of antipsychotic (e.g., olanzapine, perphenazine) and newer glutamatergic (e.g., glycine, D-cycloserine) agents have yielded only modest improvements in limited social and non-social cognitive domains that might, in part reflect repeated testing (9, 10, 11, 12). In addition, while several effective cognitive rehabilitation approaches exist for schizophrenia (13), the efficacy of these approaches when applied in the early course of the disorder has not been thoroughly assessed. Currently, the only two published randomized controlled trials of cognitive rehabilitation in early course patients have yielded mixed results (14, 15, 16). Further, these trials have been conducted exclusively with early- or childhood-onset patients and have employed relatively short-term (3 month) interventions that focus primarily on the remediation of neurocognitive deficits in attention, memory, and executive function. Long-term trials of cognitive rehabilitation approaches for early course patients are noticeably absent, and most approaches place little to no emphasis on the remediation of social cognition, which may be key to improving functional outcome (17).

Cognitive enhancement therapy (CET; 18) is an evidence-based developmental cognitive rehabilitation approach for the remediation of social and non-social cognitive deficits in schizophrenia that has conferred significant benefits for chronically ill patients. In a two-year randomized-controlled trial with 121 outpatients with schizophrenia who had been ill for an average of 15.70±9.30 years, patients receiving CET demonstrated large and highly significant improvements in neurocognitive and social-cognitive function, as well as social adjustment (19). Further, these robust effects remained one year after treatment ended (20). Recently, we found initial support for the efficacy of CET for producing large improvements in social cognition among a preliminary sample of 38 early course schizophrenia patients who had completed 1 year of a 2-year randomized trial (21). However, data on other areas of cognition and functional outcome were not yet available for analysis, leaving open questions regarding the effects of CET on broader areas of cognition and the long-term functional significance of these initial social-cognitive effects. We now report on the complete cognitive and behavioral results from all 58 individuals who entered and were treated in this two-year trial of CET for early schizophrenia. Based on our previous study of CET with chronic outpatients, it was hypothesized that individuals receiving CET would demonstrate significant differential improvements over the course of treatment in processing speed, neurocognitive and social-cognitive function, as well as social adjustment, compared to a state-of-the-art enriched supportive control condition.

Method

Participants

Participants consisted of 58 early course outpatients who met diagnostic criteria (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV [22]) for schizophrenia (n = 38) or schizoaffective disorder (n = 20). The one-year social-cognitive effects of CET on a subset (n = 38) of these individuals have been reported on previously (21). Eligible participants included individuals stabilized on antipsychotic medication with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective, or schizophreniform disorder who had experienced their first psychotic symptoms (including duration of untreated illness) within the past 8 years, had an IQ > 80, were not abusing substances for at least 2 months prior to study enrollment, and exhibited significant social and cognitive disability on the Cognitive Style and Social Cognition Eligibility Interview (19).

Participants were young with an average age of 25.92±6.31 years, over two-thirds (n = 40) were male, and most were Caucasian (n = 40). Although participants were eligible for this study if they had their first psychotic symptoms (including duration of untreated illness) within the past 8 years, most (78%) had been ill for fewer than 5 years and the duration since first psychotic symptoms of enrolled patients was on average (3.19±2.24 years) much less than the maximal eligible illness duration. While many participants had some college education (n = 39), most were not employed at baseline (n = 43).

Measures

A comprehensive battery of cognitive and behavioral measures was used to assess the effects of CET on cognition, adjustment, and symptomatology (see Table 1). In order to avoid excessive univariate inference testing that could inflate experiment-wise error rates, internally consistent multivariate composite indexes of these domains were computed. Individual measures were selected for these composites based on previous literature identifying the important domains of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia (23), field standards for adjustment and symptom assessment (24, 25), as well as previous CET studies (19, 20). Measures showing poor reliability (interitem r ≤ .10) were excluded. Four composite indexes covering cognitive function were computed to represent speed of processing, neurocognition, dysfunctional cognitive style, and social cognition. Neurocognitive and processing speed measures reflect the relevant domains of neurocognitive impairment identified by the NIMH-MATRICS committee (26). Social cognition and cognitive style measures included those developed for our previous trial of CET, which have shown adequate reliability (19); and the NIMH-MATRICS recommended Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (27), which has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties for assessing social cognition in schizophrenia (28, 29). A single composite index was computed for social adjustment and symptomatology, respectively, from multiple measures with well-documented psychometrics. Employment data were collected using the Major Role Adjustment Inventory (30), a 22-item, clinician-rated interview covering role adjustment in the domains of employment, family and household life, and social relationships. Information collected on employment in this instrument consists of vocational status, type of occupation, and number of hours a week worked at the time of the interview. Composite indexes were scaled to a baseline mean of 50±10, with lower scores reflecting better cognitive and behavioral functioning. Social cognition, neurocognition, and processing speed composites served as primary outcome measures. Secondary outcomes included the cognitive style and social adjustment composites. Although symptomatology was assessed, differential treatment effects on symptoms were not expected.

Table 1.

Study Composite Indexes and Respective Component Measures of Cognition and Behavior.

| Composite | Description | Component Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Processing Speed: α = .69 | Reaction time measures of speed of processing and attention | Simple reaction time (fixed and variable interstimulus interval) (41); Choice reaction time (dominant and non-dominant hand) (41); Visual-spatial scanning (42) |

| Neurocognition: α = .87 | Neuropsychological measures of verbal and working memory, executive functions, language ability, psychomotor speed, and neurological soft signs | Revised Wechsler Memory Scale (43); California Verbal Learning Test (44); Revised Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (45); Trails B (46); Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (47); Tower of London (48); Neurological Evaluation Scale (49) |

| Cognitive Style: α = .77 | Behavioral measures of impoverished, disorganized, and rigid dysfunctional cognitive styles | Cognitive Style and Social Cognition Eligibility Interview (19); Cognitive Styles Inventory (19) |

| Social Cognition: α = .70 | Performance-based measures of socio-emotional processing, and behavioral measures of foresightfulness, gistfulness, and other behavioral indicators of adequate social cognition | Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (27); Social Cognition Profile (19); Cognitive Style and Social Cognition Eligibility Interview (19) |

| Social Adjustment: α = .87 | Behavioral measures of functional outcome in the domains of social and vocational functioning, and adjustment in major life roles | Social Adjustment Scale-II (25); Major Role Inventory (30); Global Assessment Scale (50); Performance Potential Inventory (19, 51) |

| Symptoms: α = .71 | Clinical and behavioral measures of positive and negative symptomatology, anxiety, depression, and self-esteem | Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (24); Wing Negative Symptoms Scale (52); Raskin Depression Scale (53); Covi Anxiety Scale (54); Patient Subjective Response Questionnaire (55) |

Treatments

Medication

All participants were maintained on Food and Drug Administration approved antipsychotic medications for the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder by a study psychiatrist. Medication changes were allowed, although every effort was made to stabilize patients on a tolerable and efficacious antipsychotic regimen prior to the initiation of psychosocial treatment. All patients were seen by a clinical nurse specialist at least biweekly to monitor medication side-effects and efficacy. Most patients (> 98%) were maintained on second-generation antipsychotics throughout the study, and no significant differences emerged with regard to antipsychotic dose, type, or clinician estimated compliance between treatment groups (see Table S1).

Cognitive enhancement therapy

CET is a comprehensive, developmental approach to the remediation of social and non-social cognitive deficits in schizophrenia that seeks to facilitate the development of adult social-cognitive milestones (e.g., perspective-taking, social context appraisal) by shifting thinking from reliance on effortful, serial processing to a “gistful” and spontaneous abstraction of social themes. The treatment consists of approximately 60 hours of computer-assisted neurocognitive training in attention, memory, and problem-solving; and 45 social-cognitive group sessions that employ in vivo learning experiences to foster the development of social wisdom and success in interpersonal interactions. A broad, theoretically-driven array of social-cognitive abilities are targeted in the social-cognitive groups, which range from abstracting the “gist” or main point in social interactions to perspective-taking, social context appraisal, and emotion management (23, 31). Patients participate actively in the social-cognitive groups by responding to unrehearsed social exchanges, presenting homework, participating in cognitive exercises that focus on experiential learning, providing feedback to peers, and chairing homework sessions. CET typically begins with approximately 3 months of weekly 1-hour neurocognitive training in attention, after which patients begin the weekly 1.5-hour social-cognitive groups. Neurocognitive training then proceeds concurrently with social-cognitive groups throughout the remaining course of treatment. A complete description of the treatment has been provided elsewhere (18).

Enriched supportive therapy

Enriched supportive therapy (EST) is an illness management and psychoeducation approach that draws upon components of the basic and intermediate phases of the demonstrably effective personal therapy (32). In this approach, patients are seen on an individual basis to learn and practice stress management techniques designed to forestall late post-discharge relapse and enhance adjustment. The EST treatment is divided into two phases. Phase I focuses on basic psychoeducation about schizophrenia, the role of stress in the disorder, and ways to avoid/minimize stress. Phase II involves a personalized approach to the identification and management of life stressors that pose particular challenges to adequate social and role functioning. Patients move through the two phases of EST at their own pace, although each phase is typically provided for a year. Phase I was designed to be provided on a weekly basis, and Phase II was provided on a biweekly basis. Although no attempt was made to match CET and EST approaches with regard to hours of treatment, EST served as the active control for this trial, in part, to control for the potential effects of illness management and education interventions on outcome (33, 34), which are provided in both CET and EST. All psychosocial interventions were administered by masters-level psychiatric nurse specialists (S.J.C., A.L.D., and S.S.H.), and clinical supervision was provided by the treatment developers (G.E.H. and D.P.G.)

Procedures

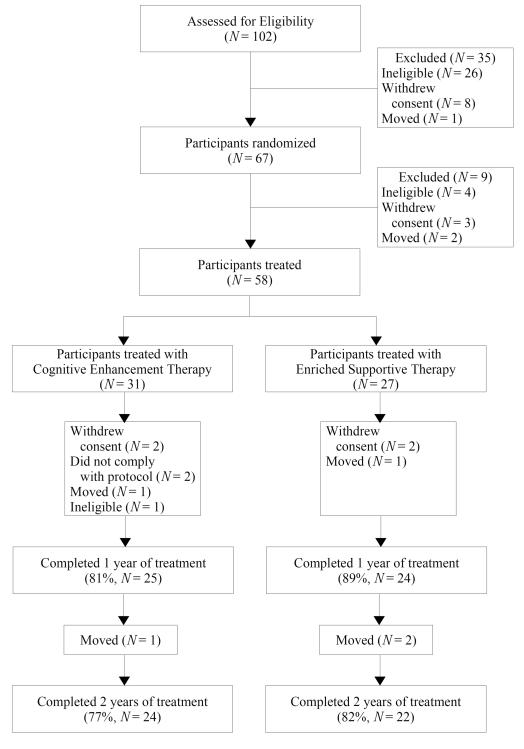

Participants were recruited from inpatient and outpatient services at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh and nearby community clinics. Upon recruitment, patients were screened for eligibility in consensus conferences utilizing videotaped interviews. Eligible participants were randomly assigned to either CET or EST by a project statistician using computer-generated random numbers, and then treated for two years and assessed annually on the aforementioned measures of cognition and behavior. One-year assessments were conducted to assess intermediate improvement. Neurocognitive and some social-cognitive assessments (i.e., MSCEIT) were completed via computer-based tests or administered by trained neuropsychologists, and the remaining assessments were completed by study clinicians who had been extensively trained in their use and were not blind to treatment assignment. Figure 1 provides a description of the participant flow throughout the study. There were no significant differences between treatment conditions with regard to demographics, attrition, or symptomatology at baseline. However, as expected, individuals assigned to CET received significantly more hours of clinician contact (see Table S1). This research was conducted between August, 2001 and September, 2007, and was approved annually by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. All patients provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Figure 1.

Participant Flow Over the Course of Two Years of a Randomized Trial of Cognitive Enhancement Therapy.

Data Analysis

Intent to treat analyses were conducted with all 58 patients who were randomized and received any exposure, regardless of how limited, to their respective treatment conditions. Treatment effects were analyzed in a sequential fashion in order to avoid excessive inference testing that could not be realistically corrected using Type I error correction algorithms. This was accomplished by first examining the main effects of treatment assignment on multivariate composite indexes of cognition and behavior using linear mixed-effects models, adjusting for potentially confounding demographic (age, gender, illness duration, and IQ) and medication (dose) effects. Subsequently, univariate main effects within composites were examined using the same mixed-effects strategy, only for those domains that demonstrated significant multivariate effects. All mixed-effects analyses used random intercept and slope models, and employed an autoregressive error structure most suitable for longitudinal data (35). Skewed data were handled using non-linear or rank transformations, and neuropsychological and processing speed outliers were handled by winsorization (36).

Results

Main Effects on Composite Indexes of Cognition and Behavior

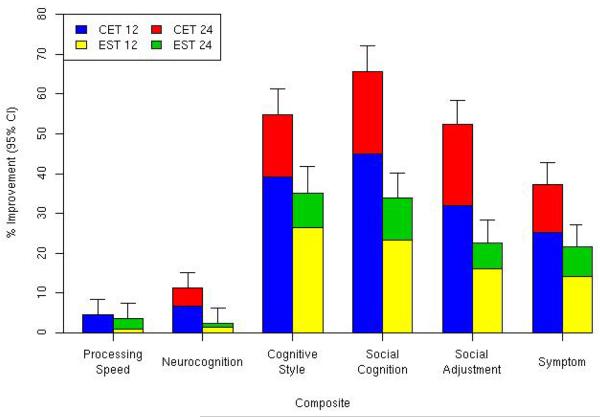

We began our analysis of the effects of CET and EST by first examining their differential effects on multivariate composite indexes of cognition and behavior. As can be seen in Table 2, during the first year of treatment individuals receiving CET displayed significant and medium to large differential improvements in dysfunctional cognitive style, social cognition, social adjustment, and symptomatology compared to those receiving EST. After 2 years of treatment, highly significant and large differential effects were observed favoring CET for improving composite indexes of social cognition, cognitive style, social adjustment, and symptomatology (see Figure 2). In addition, CET patients demonstrated significant and medium-sized differential improvement on the neurocognitive composite by the second year of treatment.

Table 2.

Effects of Cognitive Enhancement Therapy and Enriched Supportive Therapy on Composite Indexes of Cognition and Behavior.

| CET |

EST |

Between-Group Difference |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Year 1 | Year 2 | Baseline | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 1 | Year 2 | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Composite | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | t a | p | d | t a | p | d |

| Processing Speed | 49.73 | 9.18 | 47.53 | 8.23 | 49.16 | 11.58 | 52.41 | 10.88 | 51.93 | 10.74 | 50.58 | 10.20 | .73 | .470 | .17 | −.62 | .540 | −.13 |

| Neurocognition | 50.39 | 9.47 | 47.01 | 8.81 | 44.67 | 7.55 | 47.15 | 10.63 | 46.52 | 9.64 | 46.04 | 9.93 | 1.73 | .087 | .27 | 2.32 | .023 | .46 |

| Cognitive Style | 49.83 | 10.92 | 30.26 | 11.46 | 22.59 | 11.47 | 48.62 | 9.04 | 35.82 | 14.19 | 31.53 | 13.84 | 2.32 | .023 | .68 | 3.03 | .003 | 1.02 |

| Social Cognition | 48.76 | 11.61 | 27.34 | 10.50 | 17.87 | 13.50 | 48.63 | 7.95 | 37.97 | 11.89 | 33.28 | 11.66 | 4.15 | < .001 | 1.08 | 4.98 | < .001 | 1.55 |

| Social Adjustment | 49.57 | 9.09 | 33.77 | 10.76 | 23.56 | 13.40 | 47.07 | 11.08 | 39.51 | 11.15 | 36.44 | 11.34 | 3.53 | .001 | .82 | 5.16 | < .001 | 1.54 |

| Symptoms | 48.93 | 10.32 | 36.56 | 10.33 | 30.75 | 10.68 | 48.33 | 9.82 | 41.45 | 11.46 | 37.84 | 8.46 | 2.07 | .042 | .55 | 2.74 | .008 | .77 |

Note. Means are adjusted from linear mixed-effects models accounting for demographic effects and potential medication confounders. Composite scores are standardized with a baseline mean of 50±10, with lower scores indicating better cognitive or behavioral functioning.

Degrees of freedom for t-tests from mixed-effects models are df = 80 for processing speed, df = 81 for neurocognition, and df = 82 cognitive style, social cognition, social adjustment, and symptom composites.

CET = Cognitive enhancement therapy

EST = Enriched supportive therapy

Figure 2.

Differential Improvement of Persons Receiving Cognitive Enhancement Therapy Versus Enriched Supportive Therapy on Composite Indexes of Cognition and Behavior.

Main Effects on Univariate Components of Cognitive and Behavioral Composite Indexes

Having demonstrated significant and large effects favoring CET for improving cognition and behavior on multivariate composite indexes by the second year of treatment, we proceeded to investigate the nature of these effects by examining differential rates of improvement for the individual components of these composites. As can be seen in Table 3, differential improvement on the neurocognitive composite was reserved for select measures of verbal memory, executive functioning and planning, and neurological soft signs. Differential effects on the cognitive style composite were centered around improving problems with motivation and disorganization, whereas effects on the social cognition composite were more broad and ranged from significant improvements in social and emotional information processing to improved interpersonal effectiveness and foresightfulness. Importantly, these large social-cognitive effects were evident not only on clinician-rated measures of social cognition, but were also observed on the performance-based MSCEIT.

Table 3.

Two-Year Univariate Effects of Cognitive Enhancement Therapy and Enriched Supportive Therapy on Cognition and Behavior.

| CET |

EST |

Between-Group Difference | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Year 2 | Baseline | Year 2 | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | t | df | p |

| Neurocognition | |||||||||||

| Verbal Memory | |||||||||||

| WMS-R: Immediate recalla | 21.68 | 7.25 | 22.52 | 5.85 | 23.41 | 7.23 | 23.76 | 8.57 | −.25 | 74 | .806 |

| WMS-R: Delayed recalla | 15.92 | 8.13 | 18.32 | 6.46 | 18.85 | 8.24 | 21.18 | 8.83 | −.03 | 74 | .974 |

| CVLT: List A total recallb | 50.56 | 12.95 | 52.42 | 9.37 | 54.44 | 11.97 | 50.60 | 12.56 | −1.77 | 79 | .080 |

| CVLT: Short-term free recallc | 9.86 | 3.21 | 11.34 | 2.37 | 10.77 | 3.65 | 10.29 | 4.07 | −2.72 | 79 | .008 |

| CVLT: Long-term free recallc | 10.20 | 3.41 | 10.83 | 2.76 | 11.50 | 3.60 | 10.99 | 3.46 | −1.40 | 79 | .166 |

| Working Memory | |||||||||||

| WAIS-R: Digit spand | 10.20 | 2.19 | 10.25 | 2.00 | 9.68 | 2.28 | 10.13 | 2.34 | .76 | 79 | .447 |

| Language | |||||||||||

| WAIS-R: Vocabularyd | 9.93 | 2.66 | 10.13 | 1.80 | 9.66 | 2.82 | 9.85 | 2.79 | −.03 | 79 | .976 |

| Executive Functions/Planning | |||||||||||

| Trails B time, se | 63.71 | 21.31 | 49.60 | 10.92 | 61.25 | 24.59 | 59.06 | 24.47 | 2.08 | 79 | .040 |

| WAIS-R: Picture arrangementd | 8.97 | 2.66 | 10.60 | 2.82 | 9.85 | 2.67 | 11.03 | 2.06 | −.64 | 79 | .525 |

| WCST: Categories achievedf | .74 | .33 | .81 | .28 | .77 | .32 | .75 | .32 | −.86 | 80 | .393 |

| WCST: Perseverative errorsg | 11.35 | 8.14 | 10.08 | 7.04 | 9.62 | 6.25 | 8.80 | 6.32 | .20 | 80 | .842 |

| WCST: Non-perseverative errorsg | 11.13 | 7.65 | 9.37 | 6.63 | 8.48 | 6.87 | 9.46 | 6.52 | 1.03 | 80 | .306 |

| WCST: % conceptual responsesh | 67.66 | 12.76 | 68.92 | 14.50 | 66.63 | 12.23 | 69.62 | 12.96 | .37 | 79 | .712 |

| TOL: Ratio of initiation to execution timei | −2.04 | .60 | −1.37 | .70 | −1.77 | .57 | −1.56 | .66 | −2.10 | 80 | .039 |

| TOL: Move scorej | 41.64 | 19.34 | 38.47 | 21.84 | 39.04 | 16.58 | 39.23 | 25.80 | .42 | 80 | .674 |

| Psychomotor Speed | |||||||||||

| WAIS-R: Digit symbold | 8.88 | 2.47 | 10.14 | 3.08 | 8.43 | 2.60 | 9.71 | 2.97 | .03 | 79 | .976 |

| Neurological Soft Signs | |||||||||||

| NES: Cognitive-perceptualk | .51 | .36 | .16 | .29 | .40 | .37 | .37 | .30 | 2.48 | 66 | .016 |

| NES: Repetition-motork | .26 | .36 | .19 | .33 | .14 | .28 | .33 | .37 | 2.35 | 66 | .022 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Cognitive Style | |||||||||||

| Cognitive Style Eligibility Criteria | |||||||||||

| Impoverished stylel | 10.72 | 2.79 | 6.12 | 2.22 | 10.80 | 2.58 | 7.87 | 2.58 | 2.51 | 79 | .014 |

| Disorganized stylel | 10.11 | 2.09 | 5.93 | 2.32 | 9.96 | 1.97 | 7.04 | 2.61 | 2.04 | 79 | .044 |

| Rigid stylel | 8.67 | 2.36 | 6.11 | 1.89 | 8.29 | 2.68 | 6.67 | 2.17 | 1.37 | 79 | .173 |

| Total impairment, disability, and social handicapm | 29.50 | 5.01 | 18.18 | 4.64 | 29.11 | 4.34 | 21.59 | 5.98 | 2.57 | 79 | .012 |

| Highest cognitive style scorel | 11.88 | 1.75 | 7.41 | 1.94 | 11.79 | 1.48 | 8.85 | 2.06 | 2.85 | 79 | .006 |

| Cognitive Styles Inventoryn | |||||||||||

| Problems getting started | 3.20 | .82 | 1.84 | .49 | 3.18 | .71 | 2.50 | .71 | 3.17 | 81 | .002 |

| Problems focusing | 2.60 | .66 | 1.83 | .60 | 2.54 | .70 | 2.07 | .71 | 1.73 | 81 | .088 |

| Problems changing ideas | 2.29 | .56 | 1.85 | .56 | 2.19 | .65 | 2.00 | .52 | 1.30 | 81 | .196 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Social Cognition | |||||||||||

| Social Cognition Profileo | |||||||||||

| Tolerant factor | 3.30 | .50 | 4.22 | .54 | 3.12 | .65 | 3.59 | .57 | −3.01 | 82 | .004 |

| Supportive factor | 2.69 | .56 | 4.01 | .58 | 2.63 | .45 | 3.31 | .35 | −4.54 | 82 | < .001 |

| Perceptive factor | 2.42 | .51 | 3.88 | .62 | 2.37 | .61 | 3.20 | .56 | −4.07 | 82 | < .001 |

| Confident factor | 2.37 | .54 | 3.74 | .55 | 2.27 | .50 | 3.05 | .55 | −3.53 | 82 | .001 |

| Social Cognition Eligibility Criteriao | |||||||||||

| Interpersonal ineffectiveness | 3.71 | .73 | 2.22 | .70 | 3.66 | .76 | 3.01 | .77 | 3.58 | 79 | .001 |

| Lack of foresight | 3.59 | .67 | 2.19 | .79 | 3.63 | .63 | 2.78 | .61 | 2.09 | 79 | .040 |

| Gist extraction deficits | 3.47 | .93 | 1.98 | .81 | 3.47 | .94 | 2.46 | .96 | 1.50 | 79 | .137 |

| Adjustment to disability | 3.04 | .77 | 1.74 | .66 | 2.97 | .81 | 2.08 | .64 | 1.42 | 79 | .158 |

| MSCEITp | |||||||||||

| Perceiving emotions | 91.51 | 15.99 | 95.86 | 17.25 | 97.77 | 16.46 | 92.90 | 15.96 | −2.02 | 79 | .047 |

| Facilitating emotions | 90.38 | 18.50 | 94.09 | 17.56 | 99.63 | 16.28 | 99.22 | 15.73 | −1.00 | 79 | .321 |

| Understanding emotions | 87.76 | 11.77 | 94.19 | 9.69 | 88.98 | 12.79 | 87.32 | 14.18 | −2.30 | 79 | .024 |

| Managing emotions | 88.40 | 13.17 | 97.01 | 10.93 | 87.63 | 10.98 | 88.71 | 12.80 | −2.74 | 79 | .008 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Social Adjustment | |||||||||||

| Employment | |||||||||||

| MRAI: Employmenq | 2.96 | 1.30 | 1.81 | 1.14 | 2.86 | 1.36 | 2.60 | 1.20 | 2.18 | 80 | .032 |

| PPI: Global work readinessr | 1.52 | .73 | 3.33 | 1.27 | 1.82 | 1.00 | 2.63 | 1.33 | −2.87 | 81 | .005 |

| SAS-II: Work affinitys | 1.17 | .72 | .31 | .65 | 1.04 | .93 | .99 | .72 | 1.67 | 27 | .106 |

| Social Functioning | |||||||||||

| MRAI: Relationships outside the homet | 2.68 | .89 | 1.48 | .66 | 2.50 | .89 | 2.28 | 1.04 | 3.19 | 82 | .002 |

| PPI: Social functioningr | 2.57 | .53 | 3.93 | .58 | 2.68 | .56 | 3.30 | .64 | −4.52 | 81 | < .001 |

| SAS-II: Interpersonal anguishs | 1.07 | .64 | .62 | .49 | .85 | .64 | .79 | .62 | 2.41 | 82 | .018 |

| SAS-II: Sexual relationsu | 3.34 | 1.31 | 2.70 | 1.65 | 3.69 | 1.03 | 3.43 | 1.25 | .98 | 80 | .329 |

| SAS-II: Primary relationss | .98 | .74 | .49 | .60 | 1.05 | .78 | .67 | .49 | .46 | 59 | .646 |

| SAS-II: Social leisures | 1.51 | .84 | .66 | .70 | 1.09 | .47 | 1.14 | .68 | 3.92 | 82 | < .001 |

| Global Functioning | |||||||||||

| MRAI: Major role adjustmentv | 6.04 | .97 | 3.81 | 1.91 | 6.10 | 1.23 | 5.16 | 1.52 | 2.67 | 82 | .009 |

| MRAI: Overall functioningt | 4.82 | .35 | 3.77 | 1.18 | 4.54 | .75 | 4.30 | .74 | 3.24 | 82 | .002 |

| Global Assessment Scalew | 51.56 | 8.11 | 69.18 | 8.20 | 53.81 | 7.55 | 61.39 | 9.62 | −4.29 | 82 | < .001 |

| Mental status (PPI)r | 2.89 | .43 | 4.12 | .52 | 2.98 | .51 | 3.69 | .57 | −3.73 | 81 | < .001 |

| Activities of Daily living (PPI)r | 2.62 | 1.16 | 4.25 | .86 | 2.56 | 1.21 | 3.33 | 1.13 | −3.40 | 81 | .001 |

| Instrumental task performance (PPI)r | 2.30 | .59 | 3.93 | .73 | 2.45 | .75 | 3.32 | .80 | −3.99 | 81 | < .001 |

| Self care (SAS-II)s | 1.05 | .65 | .58 | .43 | 1.14 | .78 | .95 | .73 | 1.42 | 82 | .159 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Symptomatology | |||||||||||

| Anxiety/Depression | |||||||||||

| BPRS Anxiety-depressionx | 2.61 | .85 | 1.97 | .82 | 2.41 | .68 | 2.28 | .64 | 2.24 | 82 | .028 |

| Raskin depressiony | 6.63 | 2.77 | 3.85 | 1.24 | 6.21 | 1.98 | 4.70 | 1.49 | 1.96 | 82 | .054 |

| Covi anxiety | 5.72 | 2.08 | 4.79 | 1.43 | 5.89 | 2.22 | 5.35 | 1.53 | .53 | 82 | .595 |

| Negative Symptoms | |||||||||||

| BPRS Withdrawal-retardationx | 2.74 | 1.20 | 1.63 | .60 | 2.94 | 1.06 | 2.30 | .78 | 1.99 | 82 | .050 |

| Wing negative symptomsz | 18.30 | 4.14 | 11.01 | 3.44 | 18.25 | 3.63 | 13.99 | 3.79 | 2.47 | 82 | .016 |

| Thought Disorder (BPRS)x | 2.12 | 1.14 | 1.71 | .83 | 2.12 | 1.07 | 1.74 | .80 | .16 | 82 | .872 |

| Hostility (BPRS)x | 1.61 | .62 | 1.47 | .51 | 1.75 | .94 | 1.51 | .62 | −.64 | 82 | .527 |

| Global Degree of Illnessx | 4.22 | .69 | 2.61 | .87 | 4.27 | .75 | 3.22 | .90 | 2.42 | 80 | .018 |

| Self-Esteemaa | 3.08 | .80 | 3.90 | .76 | 3.35 | .71 | 3.74 | .65 | −1.97 | 74 | .053 |

Note. Means are adjusted from linear mixed-effects models accounting for demographic effects and potential medication confounders.

Possible scores range from 0 to 50, with higher scores indicating better neurocognitive performance.

Possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better neurocognitive performance.

Possible scores range from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating better neurocognitive performance.

Possible scores range from 1 to 19, with higher scores indicating better neurocognitive performance.

Scores are given in seconds, with higher scores indicating worse neurocognitive performance.

WCST categories achieved was rank order transformed due to non-normal distributions. Possible scores range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating better neurocognitive performance.

Possible scores range from 0 to 28, with higher scores indicating worse neurocognitive performance.

Possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better neurocognitive performance.

TOL ratio of initiation to execution time was log transformed due to skewness. Higher scores indicate better neurocognitive performance.

Possible scores range from 0 to 189, with higher scores indicating worse neurocognitive performance.

Possible scores range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating more neurological soft signs.

Possible scores range from 3 to 15, with higher scores indicating greater cognitive dysfunction.

Possible scores range from 9 to 45, with higher scores indicating greater impairment from cognitive dysfunction.

Possible scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater cognitive dysfunction.

Possible scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating worse social-cognitive functioning.

Scores are scaled with a mean of 100±50, with higher scores indicating better social-cognitive functioning.

Possible scores range from 1 to 4, with higher scores indicating worse adjustment.

Possible scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating better adjustment.

Possible scores range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating worse adjustment.

Possible scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating worse adjustment.

Possible scores range from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating worse adjustment.

Possible scores range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating worse adjustment.

Possible scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better adjustment.

Possible scores range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating greater symptomatology.

Possible scores range from 3 to 15, with higher scores indicating greater symptomatology.

Possible scores range from 6 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater symptomatology.

Possible scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater self-esteem.

BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, CET = Cognitive enhancement therapy, CVLT = California Verbal Learning Test, EST = Enriched supportive therapy, MRAI = Major Role Adjustment Inventory, MSCEIT = Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test, NES = Neurological Evaluation Scale, PPI = Performance Potential Inventory, SAS-II = Social Adjustment Scale-II, TOL = Tower of London, WAIS-R = Revised Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, WCST = Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, WMS-R = Revised Wechsler Memory Scale

Improvements favoring CET on behavioral composites of social adjustment and symptomatology were also broad. Significant effects were observed favoring CET with regard to employment, social functioning, global adjustment, activities of daily living, and instrumental task performance (see Table 3). A closer inspection of effects on employment indicated that significantly more patients receiving CET (54%) were actively engaged in paid, competitive employment (assessed through clinician interviews using the Major Role Adjustment Inventory [30]) at the end of 2 years of treatment, compared to those receiving EST (18%), χ2 = 4.93, df = 1, p = .026. With regard to the symptom composite, significant differential effects favoring CET were observed on multiple measures of negative symptoms, as well as measures of anxiety and depression.

Discussion

Cognitive remediation has emerged as an effective method for ameliorating the cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia that undermine functional recovery (13). Short-term trials conducted with childhood/early-onset patients focusing on neurocognitive dysfunction have suggested the potential benefits of cognitive remediation at the earliest stages of the illness (14, 15, 16). To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the long-term effects of a comprehensive neurocognitive and social-cognitive rehabilitation program on broad domains of cognition and functioning when applied in early schizophrenia. Results from this two-year trial broadly support our hypotheses that CET would improve cognitive and behavioral outcomes among this population. Individuals receiving CET demonstrated substantial cognitive gains during the two years of treatment, particularly in social cognition, where a broad array of social-cognitive improvements were found on multiple performance-based and clinician-rated measures. Most importantly, while specific mediator analyses are needed and will be the focus of subsequent reports, these cognitive gains appear to have translated into significant reductions in disability. Individuals in CET exhibited marked improvements in employment, social functioning, and global adjustment, as well as reductions in negative symptoms compared to their EST counterparts. These effects, which could not be accounted for by group differences in antipsychotic medication use or differential rates of attrition, highlight the potential functional benefits of sufficient exposure to early cognitive rehabilitation in schizophrenia.

It is important to note that the largest cognitive effects observed during CET were in social cognition, a domain that has been linked to functional outcome (37) and remained largely unresponsive to pharmacological treatment (38). While neurocognitive effects were moderate in size, it was surprising that early course patients receiving CET did not show any significant improvement in processing speed, which is in contrast to our previous study with long-term patients (19). Comparison of average processing speed scores between this early course sample and those in our previous study indicated that early course patients performed significantly better on every measure of processing speed at baseline compared to chronic patients, all t < −2.96, all df = 56, all p < .005. In fact, the pre-treatment means of individuals receiving CET in this study were comparable to the processing speed of chronic patients after two years of CET treatment (19), pointing to the possibility of a ceiling effect for speed of processing. That processing speed and other aspects of attention are less impaired among early course patients is not novel (6, 39, 40), and this research suggests that more complex social-cognitive processes may be the most critical targets for early intervention programs. CET may serve as a key adjunct to pharmacotherapy in this regard.

Despite the efficacy of CET for improving cognition and behavior among early course patients, the results of this research need to be interpreted in the context of a number of limitations. The patients studied were mostly male and Caucasian, and the results of this investigation may not generalize to more diverse samples. Treatment groups were also not matched for the number of hours of clinician contact, therefore results could reflect the non-specific effects of increased clinician contact on outcome. In addition, assessing clinicians were not blind to the treatments to which patients were assigned. As such, rater bias cannot be ruled out as a possible explanation for treatment effects. However, effects on performance-based measures of social cognition were equally strong as clinician-rated measures; and social adjustment effects were seen on an array of different measures, many of which leave little room for rater bias (e.g., employment - although employment data did rely largely on self-report). Further, robust neurocognitive effects were also found on performance-based measures of cognition, arguing against a substantial rater bias.

Increased familiarity with computerized testing associated with CET exposure may also explain some improvements in performance on computer-based neuropsychological tests. However, CET effects on neurocognition were seen primarily on paper and pencil examinations that bear little resemblance to computerized training software, suggesting that while it is possible CET influenced test-taking behavior in general, it is less likely that differential neurocognitive improvement favoring CET was the result of enhanced computer literacy or familiarity. In addition, within-composite analyses need to be interpreted with caution, as while a hierarchical approach was used to avoid excessively inflating Type I error, multiple univariate tests were conducted on within-composite measures. Finally, this research was characterized by a somewhat modest sample size (n = 58), which may have precluded the detection of smaller treatment effects. However, to our knowledge this is the largest and longest early course study of cognitive rehabilitation to date, and our results indicate that our a priori power analyses based on previous studies (19) guided us toward a sample size that was sufficient to reliably detect the medium to large CET effects observed in this study. Consequently, it would appear that a sufficient number of individuals were studied to provide an adequate evaluation of the efficacy of CET in early schizophrenia. A one-year post-treatment follow-up study is currently being completed to ascertain the durability of these effects and determine whether they are comparable to the sustained benefits achieved by chronic patients (20).

Conclusions

CET is recovery-phase treatment for the remediation of social and non-social cognitive deficits among stable outpatients with schizophrenia. The results of this investigation suggest the early application of CET may confer substantial benefits in cognitive functioning and broad domains of functional outcome among this population. Sufficient exposure to cognitive rehabilitation may be a vital, yet overlooked component to early intervention programs, ultimately providing the critical ingredients needed to help individuals recover from this disorder.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMH grants MH 60902 (MSK) and MH 79537 (SME). We thank Konasale Prasad, M.D., Haranath Parepally, M.D., Diana Dworakowski, M.S., Mary Carter, Ph.D., Sara Fleet, M.S., and Michele Bauer for their help in various aspects of the study. We also thank our Department chairman, David Kupfer, M.D. for extended support throughout the project, as well as the many patients who participated in this research and the dedication they showed to their recovery, which was a constant source of inspiration.

Funding Source: National Institute of Mental Health

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest with this research.

References

- 1.Rupp A, Keith SJ. The costs of schizophrenia: Assessing the burden. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1993;16:413–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGlashan TH, Fenton WS. Subtype progression and pathophysiologic deterioration in early schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1993;19:71–84. doi: 10.1093/schbul/19.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieberman JA. Is schizophrenia a neurodegenerative disorder? A clinical and neurobiological perspective. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46:729–739. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: A critical review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1785–1804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGlashan TH, Johannessen JO. Early detection and intervention with schizophrenia: Rationale. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1996;22:201–222. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saykin AJ, Shtasel DL, Gur RE, et al. Neuropsychological deficits in neuroleptic naive patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:124–131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950020048005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoff AL, Svetina C, Shields G, et al. Ten year longitudinal study of neuropsychological functioning subsequent to a first episode of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;78:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, et al. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: Are we measuring the right stuff? Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2000;26:119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keefe RSE, Seidman LJ, Christensen BK, et al. Comparative effect of atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs on neurocognition in first-episode psychosis: A randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus low doses of haloperidol. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:985–995. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herbener ES, Hill SK, Marvin RW, et al. Effects of antipsychotic treatment on emotion perception deficits in first-episode schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1746–1748. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg TE, Goldman RS, Burdick KE, et al. Cognitive improvement after treatment with second-generation antipsychotic medications in first-episode schizophrenia: Is it a practice effect. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1115–1122. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchanan RW, Javitt DC, Marder SR, et al. The cognitive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia trial (CONSIST): The efficacy of glutamatergic agents for negative symptoms and cognitive impairments. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1593–1602. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06081358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGurk SR, Twamley EW, Sitzer DI, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1791–1802. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07060906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueland T, Rund BR. A controlled randomized treatment study: The effects of a cognitive remediation program on adolescents with early onset psychosis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2004;109:70–74. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690x.2003.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ueland T, Rund BR. Cognitive remediation for adolescents with early onset psychosis: a 1-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2005;111:193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wykes T, Newton E, Landau S, et al. Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) for young early onset patients with schizophrenia: An exploratory randomized controlled trial. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;94:221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couture SM, Penn DL, Roberts DL. The functional significance of social cognition in schizophrenia: A review. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:S44–63. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP. Cognitive enhancement therapy: the training manual. Authors; University of Pittsburgh Medical Center: 2006. Available through www.CognitiveEnhancementTherapy.com. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogarty GE, Flesher S, Ulrich R, et al. Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia. Effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:866–876. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP, Eack SM. Durability and mechanism of effects of cognitive enhancement therapy. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:1751–1757. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.12.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eack SM, Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP, et al. Cognitive enhancement therapy improves emotional intelligence in early course schizophrenia: Preliminary effects. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;89:308–311. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hogarty GE, Flesher S. Developmental theory for a cognitive enhancement therapy of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1999;25:677–692. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychological Reports. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schooler N, Weissman M, Hogarty GE. In: Social adjustment scale for schizophrenics, in Resource material for community mental health program evaluators, DHHS Pub. No. (ADM) 79328. Hargreaves WA, Attkisson CC, Sorenson J, editors. National Institute of Mental Health; Rockville, MD: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Gold JM, et al. Approaching a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials in schizophrenia: The NIMH-MATRICS conference to select cognitive domains and test criteria. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;56:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR, et al. Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0. Emotion. 2003;3:97–105. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, et al. The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery, part 1: Test selection, reliability, and validity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:203–213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eack SM, Greeno CG, Pogue-Geile MF, et al. Assessing social-cognitive deficits in schizophrenia with the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test. Schizophrenia Bulletin. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn091. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hogarty GE, Goldberg SC, Schooler NR, et al. Drug and sociotherapy in the aftercare of schizophrenic patients: III. Adjustment of nonrelapsed patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1974;31:609–618. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760170011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Selman RL, Schultz LH. Making a friend in youth. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hogarty GE. Personal Therapy for schizophrenia and related disorders: A guide to individualized treatment. Guilford; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hogarty GE, Kornblith SJ, Greenwald D, et al. Three-year trials of personal therapy among schizophrenic patients living with or independent of family: I. Description of study and effects of relapse rates. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1504–1513. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hogarty GE, Greenwald D, Ulrich RF, et al. Three-year trials of personal therapy among schizophrenic patients living with or independent of family: II. Effects of adjustment of patients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1514–1524. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raudenbush DSW, Bryk DAS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dixon WJ, Tukey JW. Approximate behavior of the distribution of winsorized t (trimming/winsorization 2) Technometrics. 1968;10:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sergi MJ, Rassovsky Y, Nuechterlein KH, et al. Social perception as a mediator of the influence of early visual processing on functional status in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:448–454. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sergi MJ, Green MF, Widmark C, et al. Cognition and neurocognition: effects of risperidone, olanzapine, and haloperidol. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007a;164:1585–1592. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brewer WJ, Francey SM, Wood SJ, et al. Memory impairments identified in people at ultra-high risk for psychosis who later develop first-episode psychosis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:71–78. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albus M, Hubmann W, Ehrenberg C, et al. Neuropsychological impairment in first-episode and chronic schizophrenic patients. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1996;246:249–255. doi: 10.1007/BF02190276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ben-Yishay Y, Piasetsky EB, Rattok J. In: A systematic method for ameliorating disorders in basic attention, in Neuropsychological rehabilitation. Meir MJ, Benton AL, Diller L, editors. Guilford Press; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bracy OL. PSSCogRehab [computer software] Psychological Software Services Inc; Indianapolis, IN: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. Psychological Corp; San Antonio, TX: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, et al. California Verbal Learning Test manual. Psychological Corp; San Antonio, TX: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. Psychological Corp; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reitan RM, Waltson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. Neuropsychology Press; Tucson, AZ: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, et al. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test manual: Revised and expanded. Psychological Assessment Resources Inc; Odessa, FL: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Culbertson WC, Zillmer EA. Tower of London-DX manual. 1996. Unpublished manuscript. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buchanan RW, Heinrichs DW. The Neurological Evaluation Scale (NES): A structured instrument for the assessment of neurological signs in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 1989;27:335–350. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al. The Global Assessment Scale: A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1976;33:766–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770060086012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Department of Health and Human Services . Disability evaluation under social security. Author; Washington, DC: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wing JK. A simple and reliable subclassification of chronic schizophrenia. Journal of Mental Science. 1961;107:862–875. doi: 10.1192/bjp.107.450.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raskin A, Schulterbrandt J, Reatig N, et al. Replication of factors of psychopathology in interview, ward behavior and self-report ratings of hospitalized depressives. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1969;148:87–98. doi: 10.1097/00005053-196901000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lipman RS. Differentiating anxiety and depression in anxiety disorders: use of rating scales. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1982;18:69–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hogarty GE, McEvoy JP, Ulrich RF, et al. Pharmacotherapy of impaired affect in recovering schizophrenic patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:29–41. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950130029004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.