Abstract

Background

Cultural competency is an important skill that prepares physicians to care for patients from diverse backgrounds.

Objective

We reviewed Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) program requirements and relevant documents from the ACGME website to evaluate competency requirements across specialties.

Methods

The program requirements for each specialty and its subspecialties were reviewed from December 2011 through February 2012. The review focused on the 3 competency domains relevant to culturally competent care: professionalism, interpersonal and communication skills, and patient care. Specialty and subspecialty requirements were assigned a score between 0 and 3 (from least specific to most specific). Given the lack of a standardized cultural competence rating system, the scoring was based on explicit mention of specific keywords.

Results

A majority of program requirements fell into the low- or no-specificity score (1 or 0). This included 21 core specialties (leading to primary board certification) program requirements (78%) and 101 subspecialty program requirements (79%). For all specialties, cultural competency elements did not gravitate toward any particular competency domain. Four of 5 primary care program requirements (pediatrics, obstetrics-gynecology, family medicine, and psychiatry) acquired the high-specificity score of 3, in comparison to only 1 of 22 specialty care program requirements (physical medicine and rehabilitation).

Conclusions

The degree of specificity, as judged by use of keywords in 3 competency domains, in ACGME requirements regarding cultural competency is highly variable across specialties and subspecialties. Greater specificity in requirements is expected to benefit the acquisition of cultural competency in residents, but this has not been empirically tested.

Editor’s Note: The online version of this article contains a table of cultural competency scoring of health care domains in all accredited ACGME programs (20KB, docx) developed from this study.

What was known

Cultural competency is an important skill that prepares physicians to care for patients from diverse backgrounds.

What is new

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) program requirements for each specialty and its subspecialties were reviewed for presence and specificity of keywords in 3 competency domains relevant to culturally competent care: professionalism, interpersonal and communication skills, and patient care.

Limitations

Data were collected from 2011 to 2012 and may not reflect recent revisions to the program requirements; scoring system is not validated.

Bottom line

The degree of specificity in ACGME requirements regarding cultural competency is highly variable across specialties and subspecialties.

Introduction

Numerous studies and institutions, including the Institute of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health, have documented the potential impact of culture in both health care and the health care delivery system.1–5 The consideration of cultural factors by health care professionals is referred to as “cultural competence.”6–10 Although there currently is no standardized definition of cultural competence, the definition by Cross et al10 is commonly cited: “Cultural Competence is a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals and enables that system, agency, or those professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations.” While the manner in which cultural training should best be provided varies in the literature, the need to acknowledge the potential impact of cultural factors is widely supported.3,9,11–13

A seminal 2005 study by Weissman et al14 found that the majority of residents (96%) recognized the importance of cultural issues in health care and that 92% of them felt prepared to address general culturally related care issues; however, with regard to specific components of culturally sensitive approaches to care, only 75% responded affirmatively. An overly generic approach (ie, lack of explicit cultural training) may underestimate the diversity of the patient population and may fail to recognize variables beyond basic ethnic and cultural factors, including geography, type of institution (private and public hospitals), and specialty (psychiatry vs. surgery). Within the framework of cultural competency training, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) outlined general or common program requirements for specialty and subspecialty programs, which serve as the basis for all ACGME-accredited curricula.

This study examined the use of specific keywords in all ACGME requirements to assess the degree of specificity in current ACGME specialty and subspecialty program requirements.

Methods

Data Sources and Selection Criteria

All cultural competency data, program requirements, and related documentation in graduate medical education were obtained for ACGME-accredited specialties and subspecialties.15 An initial review of these requirements, which focused on professionalism and interpersonal and communication skills, was undertaken in 2008–2009. An update and more in-depth review (eg, adding the patient care competency) was conducted from December 2011 through February 2012. All specialties and subspecialties were included. There are 27 main specialties with 101 subspecialty programs for an aggregate of 128 specialties. According to the National Research Council and the World Health Organization (WHO), primary care specialties were identified as family medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, and psychiatry (n = 5).16,17 The remaining main specialties are classified as specialty care programs (n = 22).

The program requirements for each specialty and its respective subspecialties were searched and subsequently rated for the 3 main domains of cultural competency/cross-cultural health care: professionalism, interpersonal and communication skills, and patient care.18 Examples of notable practice in particular programs were obtained from the ACGME Review Committees.19 In scoring the inclusion criteria, we examined specific keywords of these particular themes, which included variances in spelling and usage context (eg, society, societal, social, socially, socio-): (1) society: community, family, personal, education; (2) race: ethnicity, diversity, minority; (3) religion: spiritual, beliefs; (4) class: economic, political, occupation; (5) gender/sex identity; (6) psychosocial elements: emotion, mental, behavioral; and (7) others: morality, ethics, age, and disability.

Analysis and Scoring Criteria

Using the appearance of these keywords in the specialty requirements, the lead author assigned each specialty and subspecialty a score between 0 and 3, from least specific to most specific requirements, for each domain of culturally competent health care (provided as online supplemental material). The scoring was based on explicit mention of culturally related keywords in the program requirements of each specialty and subspecialty. Redundant mention of the cultural keyword, such as reiteration or repeating the same context, was not counted toward the final score. A score of 0 signified no specificity in/no mentioning of culture or terms related to culture aside from the general guidelines of ACGME's common program requirements (CPR) or 1-year/transitional year program requirements. A score of 1 denoted a low level of specificity, which spans either only 1 domain or scant details (less than 3 keywords) in more than 1. A score of 2 typified a moderate level of specificity, which spans 2 domains and contains sufficient details (more than 3 keywords). A score of 3 exemplified a high level of specificity, which spans 3 domains with extensive details.

Results

Cultural Competency Specificity in ACGME Program Requirements

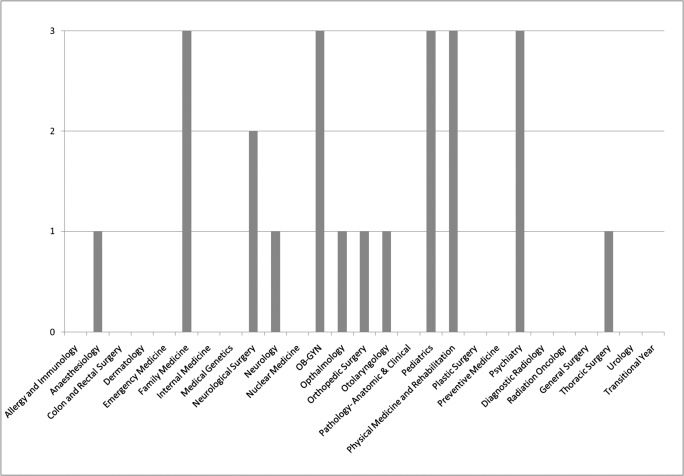

In scoring the cultural competency domains of the main ACGME-accredited program requirements, there were 12 specialties that attained the score of 1 or higher, which represented approximately 44% of the total (figure 1). The majority of specialty requirements (56%) did not contain any specificity in cultural competency elements beyond the general CPR guidelines and 21 specialties (78%) scored in the low-/no-specificity groups of 1 and 0. For all specialties, cultural competency elements did not gravitate toward any particular competency domain.

FIGURE 1.

Cultural Competency Scores of Requirements for all ACGME-Accredited Specialties (N = 27)

Score of 3 = 5 (18%); score of 2 = 1 (4%); score of 1 = 6 (22%); score of 0 = 15 (56%).

Abbreviation: OB-GYN, obstetrics and gynecology.

Primary Care and Specialty Care Program Requirements

In the comparison between requirements of the primary care group and the specialty care group, the primary care group outlined more specific and comprehensive cultural competency elements and, thus, received higher scores. Four of 5 primary care specialties acquired a score of 3, compared to only 1 of the 22 specialties in the specialty care group. Fourteen of the specialty care disciplines received a score of 0, in contrast with only 1 of 5 primary care specialties. In the primary care group, only internal medicine scored a 0; in the specialty care group, only the physical medicine and rehabilitation specialties earned a 3.

Subspecialty Requirements

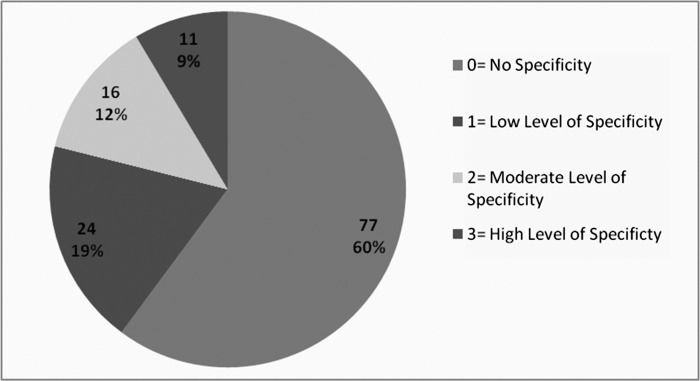

In the summary of the specialty and subspecialty requirements, the degree of specificity of the subspecialty requirements mirrored that of the main specialty programs (figure 2). Fifty-one specialties and subspecialties (40%) received a score of 1 or higher. The score of 0 was shared by the majority of all specialties and subspecialties (60%); subsequently, the scores of 1, 2, and 3, consecutively, follow in the most numerous to the least numerous of specialties and subspecialties. Furthermore, 101 (79%) scored in the low- or no-specificity group of 1 and 0. For all subspecialty groups, cultural competency elements did not gravitate toward any particular domain.

FIGURE 2.

Cultural Competency Scores of Requirements for all ACGME-Accredited Specialty and Subspecialties (N = 128)

Fifty-one specialties and subspecialties (40%) received a score of 1 or higher.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive review of cultural competency requirements of all ACGME-accredited specialties and subspecialties. Our results show wide variability in the specificity of requirements and are in agreement with previous smaller studies.14,20 Not surprisingly, primary care specialties, typically viewed as having more intensive patient interaction, made more specific mention of culture in their training requirements. Specialties like surgery were found to have less specific cultural training requirements. Whether “more specificity” can be equated with “more effective” and “more culturally competent” care is not known. Clearly, local cultural characteristics will vary and need to be considered by individual training programs.

The study by Weissman et al reported that surgical and emergency medicine residents were less likely to deem cultural issues as very important (43% and 47%, respectively) compared with the other specialties, of which 67% to 94% felt it was very important.14 Similar findings were presented in a qualitative study conducted from February 2003 through June 2003 of resident perceptions of their experiences learning cross-cultural care.20 Study participants included 68 residents (7 focus groups and 10 individual interviews) at various institutions in the United States. Mirroring the results of the quantitative study, although all of the residents viewed culture as an important factor in patient care, the degree of importance varied among the specialties. Family medicine and psychiatry residents held the strongest views on the importance of cross-cultural care in order to provide high-quality care to a diverse patient population. These 2 specialties also noted having received formal training to develop these skills. Surgical and emergency medicine residents felt that culturally sensitive care was important, but unrealistic because of time constraints. Residents from both specialties were significantly more likely to report little or no training in areas such as how to address a patient from a different culture. Emergency medicine and surgical residents reported that any skills related to cross-cultural care were largely acquired on an informal and ad hoc basis.

Our study has several limitations. The data from the ACGME program requirements were collected from December 2011 through February 2012 and may not reflect recent revisions to the program requirements. In addition, the scoring system used to rate the requirements with estimated specificity via the use of keywords is an untested method and may not be accurate. Finally, there may be significant differences in individual programs' interpretation and implementation of these program requirements.

Conclusion

This review of specialty and subspecialty requirements for key terms used to describe cultural competency in the areas of patient care, professionalism, and interpersonal and communication skills found great variation among specialties, including among primary care specialties. The majority of programs (60%) received the lowest specificity score. Whether a specificity score, low or high, correlates with the acquisition of cultural competence is unknown.

Footnotes

All authors are at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa. Adrian Jacques H. Ambrose, BA, is a third-year medical student at the John A. Burns School of Medicine; Susan Y. Lin, MA, is a PhD candidate, Department of Psychology; and Maria B. J. Chun, PhD, is a Specialist and Associate Chair, Administration and Finance, Department of Surgery.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

References

- 1.Smith WR, Betancourt JR, Wynia MK, et al. Recommendations for teaching about racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(9):654–665. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-9-200711060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(8):666–668. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Park ER. Cultural competence and health care disparities: key perspectives and trends. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2005;24(2):499–505. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saha S, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Patient centeredness, cultural competence and healthcare quality. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(11):1275–1285. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31505-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(suppl 1):181–217. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crenshaw K, Shewchuk RM, Qu H, et al. What should we include in a cultural competence curriculum? An emerging formative evaluation process to foster curriculum development. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):333–341. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182087314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O. Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003;118(4):293–302. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seeleman C, Suurmond J, Stronks K. Cultural competence: a conceptual framework for teaching and learning. Med Educ. 2009;43(3):229–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Betancourt JR. Cultural competence and medical education: many names, many perspectives, one goal. Acad Med. 2006;81(6):499–501. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000225211.77088.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cross T, Bazron B, Dennis K, Isaacs M. Towards A Culturally Competent System of Care. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Child Development Center, CASSP Technical Assistance Center; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dogra N. The views of medical education stakeholders on guidelines for cultural diversity teaching. Med Teach. 2007;29(2–3):e41–e46. doi: 10.1080/01421590601034670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betancourt JR. Cultural competence—marginal or mainstream movement. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(10):953–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kripalani S, Bussey-Jones J, Katz MG, Genao I. A prescription for cultural competence in medical education. J Gen Int Med. 2006;21(10):1116–1120. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00557.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weissman JS, Betancourt J, Campbell EG, et al. Resident physicians' preparedness to provide cross-cultural care. JAMA. 2005;294(9):1058–1067. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.9.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) List of ACGME-accredited specialties and subspecialties. http://dconnect.acgme.org/acWebsite/RRC_sharedDocs/ACGME-Accredited_Specialties_and_Subspecialties.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Research Council. Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Vol. 1996. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; Defining primary care; pp. 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Integrating mental health into primary care: a global perspective. 2008. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241563680_eng.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.ACGME. Program and institutional guidelines. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/83/ProgramandInstitutionalGuidelines.aspx. Accessed February 21, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.ACGME. Notable practices. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/192/GraduateMedicalEducation/NotablePractices.aspx. Accessed February 21, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park ER, Betancourt JR, Kim MK, Maina AW, Blumenthal D, Weissman JS. Mixed messages: residents' experiences learning cross-cultural care. Acad Med. 2005;80(9):874–880. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200509000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]