Abstract

Background

Since the legalization of abortion services in the United States, provision of abortions has remained a controversial issue of high political interest. Routine abortion training is not offered at all obstetrics and gynecology (Ob-Gyn) training programs, despite a specific training requirement by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Previous studies that described Ob-Gyn programs with routine abortion training either examined associations by using national surveys of program directors or described the experience of a single program.

Objective

We set out to identify enablers of and barriers to Ob-Gyn abortion training in the context of a New York City political initiative, in order to better understand how to improve abortion training at other sites.

Methods

We conducted in-depth qualitative interviews with 22 stakeholders from 7 New York City public hospitals and focus group interviews with 62 current residents at 6 sites.

Results

Enablers of abortion training included program location, high-capacity services, faculty commitment to abortion training, external programmatic support, and resident interest. Barriers to abortion training included lack of leadership continuity, leadership conflict, lack of second-trimester abortion services, difficulty obtaining mifepristone, optional rather than routine training, and antiabortion values of hospital personnel.

Conclusions

Supportive leadership, faculty commitment, and external programmatic support appear to be key elements for establishing routine abortion training at Ob-Gyn residency training programs.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains a sample copy of the guides used for residency program directors and residency focus groups. (27.2KB, zip)

What was known

Training in elective abortions is important for access to these services but is not provided by all obstetrics and gynecology residency programs.

What is new

Interviews identified enablers of and barriers to abortion training in a sample of New York City programs.

Limitations

New York City's environment may be more favorable to abortion training than that of other states, limiting generalizability of the findings.

Bottom line

Supportive leadership, faculty commitment, and external programmatic support appear to be enablers of abortion training, whereas barriers include leadership discontinuity or conflict, optional rather than routine training, and environmental factors.

Introduction

Since the legalization of abortion services in the United States, provision of abortions has remained a controversial issue of high political interest. The need for obstetrics and gynecology (Ob-Gyn) residents to be exposed to abortion training, however, remains supported by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.1 Since 1996, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has specified that Ob-Gyn programs must include training in induced abortions.2 Despite this, approximately one-half of Ob-Gyn programs do not provide routine abortion training.3 Currently, 14% of practicing obstetricians and gynecologists provide abortions,4 and 87% of US counties do not have a provider.5 Training inconsistencies likely are a factor contributing to the lack of access to abortion care for some areas in the United States, and it is of high social and medical significance that routine abortion training be provided.

National and local initiatives have been created to improve abortion training for Ob-Gyn residents. Since 1999, the Ryan Program has provided funding and expertise to develop abortion training at more than 60 Ob-Gyn departments in the United States, Puerto Rico, and Canada (written communication with Ryan Program employee Kristin Simonson on March 13, 2013).6 In 2002, the National Abortion and Reproductive Rights Action League of New York, now called NARAL Pro-Choice New York (NARAL/NY), obtained Mayor Michael Bloomberg's support to launch the first citywide abortion training initiative.7 Bloomberg assigned the Health and Hospitals Corporation (HHC), which manages 8 public hospitals that train Ob-Gyn residents from nearby community or academic residency programs, to coordinate the initiative. The program's aims were to develop or improve routine abortion training with respect to the full range of modern abortion services. The details of the implementation and outcomes of this initiative have been described separately.8

Previous studies that described Ob-Gyn programs with routine abortion training either examined associations based on national surveys of program directors3,9 or described a single site's experience.10 We set out to identify enablers of and barriers to Ob-Gyn residency abortion training within the context of the New York City (NYC) training initiative. To develop a more holistic account, we used a qualitative methodology and surveyed a range of respondents from multiple sites. An in-depth examination of the different factors that bear on Ob-Gyn abortion training at multiple institutions with specific training provisions will contribute to a better understanding of how to improve abortion training at other sites. Findings may improve abortion training efforts around the country and positively impact the low number of abortion providers available to US women throughout most of the country.

Methods

We obtained Institutional Review Board approval from Columbia University Medical Center and 7 of the 8 individual HHC hospital facility research review committees. One HHC program did not respond to our invitation.

Participants

We used stratified purposive sampling for enrollment of participants. We invited individuals involved in implementing the initiative: an initiative consultant, an HHC chief of staff member, a NARAL/NY employee, a Ryan Program staff member, and an Ipas program consultant (Ipas is a nongovernmental organization that aims to expand the availability, quality, and sustainability of all reproductive health services11). Next, we invited program representatives: 7 HHC Ob-Gyn departmental chiefs of service and 5 university-affiliated residency directors. We recruited 3 current and 4 prior HHC providers of induced abortion services. Six of the program directors allowed us to conduct a resident focus group interview; one program director declined an interview. Focus group interviews were arranged during the residents' protected educational time; none of the residents in attendance were excluded from participation. At the start of the interview, we described the purpose of the study and obtained oral consent from participating residents.

Data Collection

We first met with the NARAL/NY employee who was involved in the development, advocacy, and evaluative aspects of this initiative. She helped us develop detailed, semistructured interview guides regarding the content, context, and potential enablers of and barriers to abortion training. A sample copy of the guides used for residency program directors and residency focus groups is provided as online supplemental content. We then invited individual and resident informants to participate in 30- to 60-minute interviews. When possible, we audio recorded and transcribed the interviews. Interviewers took handwritten notes when participants declined the request for audio recording and at the program director's request for one resident focus group. We obtained oral consent and assured all participants that institutional and employee names would be deidentified.

Data Analysis

We engaged in an iterative and comparative form of analysis to allow themes to emerge.12 Open coding (level I) consisted of line-by-line examination of transcripts and identification of specific factors that were used as codes. During axial coding (level II), we examined open codes for the underlying explanation of how the factor posed as an enabler or barrier. We used selective coding (level III) to merge findings and classify whether they arose in the context of the initiative. We used data display tables to visually understand our results and then created a conceptual framework based on the theory that emerged. We subsequently re-reviewed transcripts to ensure theoretical consistency.

Credibility

Following the approach described by Creswell,13 we took several steps to achieve and maintain credibility, including writing subjective memos, seeking feedback from field practitioners, and corroborating our data with previous literature as data triangulation. For the interviewees who declined audio recording, we reviewed and transcribed the notes immediately after the interviews to improve accuracy.

Results

A total of 22 of 24 invited individuals (92%) participated. Of the 6 residency programs that participated in our study, 3 had routine abortion training in the form of a dedicated family planning rotation or by integration into the gynecology service rotation. The other 3 programs offered optional training: 1 program had training available on-site, and the other 2 required the resident to individually arrange participation. A total of 62 of the 150 residents (44%) at the 6 programs were available to participate in focus group interviews, and none declined participation. Individual program participation rates ranged from 25% to 58%. There was approximately equal representation across training levels: 34% postgraduate year 1 (PGY-1), 23% PGY-2, 19% PGY-3, and 24% PGY-4. Most of the residents in these programs participated in abortion services; 13% did not fully participate (opted out).

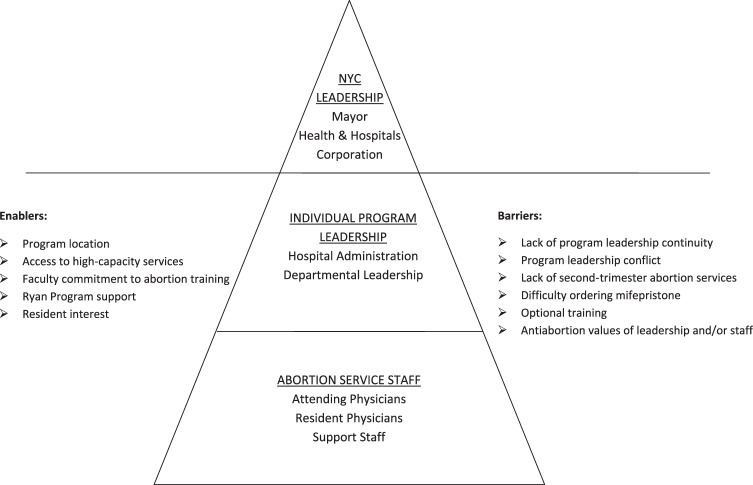

We organized the conceptual framework based on the results and theory that emerged (figure). In the figure, the pyramid's levels categorized stakeholders by their job role, displayed their authority, and reflected the relative number of individuals. Although we uncovered enablers and barriers arising at the NYC leadership level, for the purpose of this article we focused on enablers and barriers implemented by program leadership and/or abortion service staff. We present key quotations related to enablers and barriers in tables 1 and 2, respectively.

FIGURE.

Conceptual Framework of Enablers and Barriers

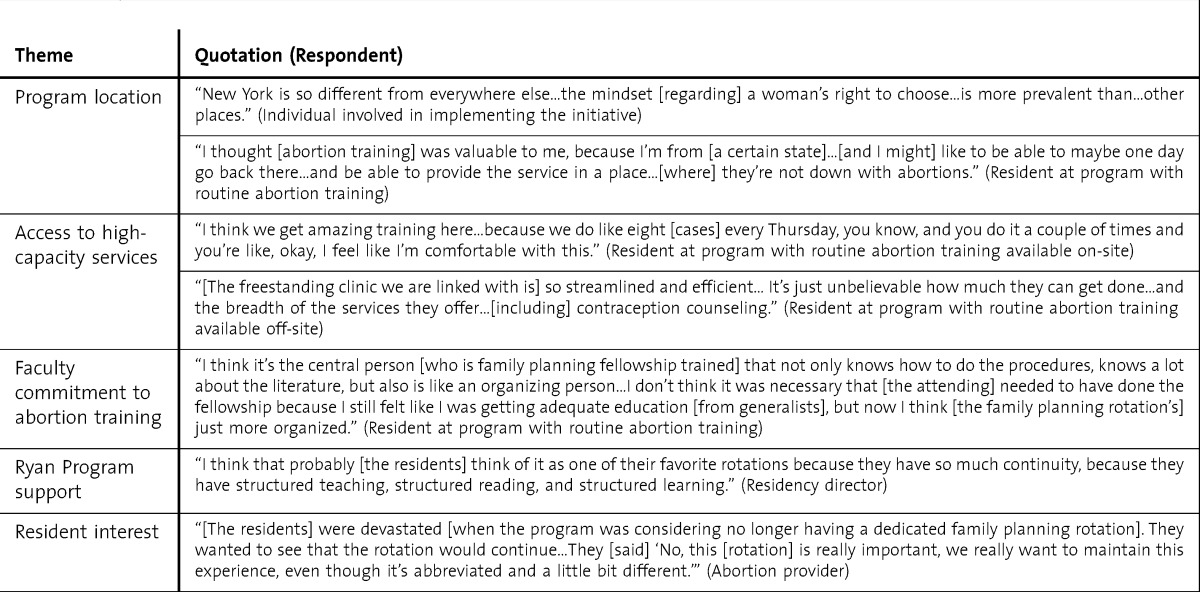

Table 1.

Key Quotations Related to Enablers

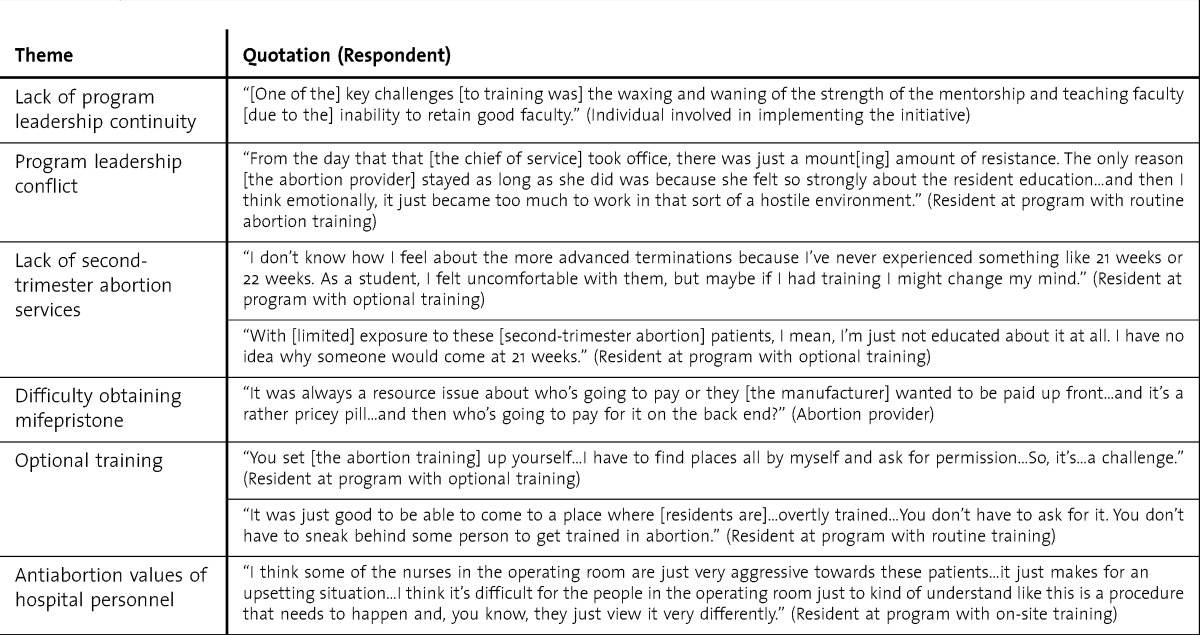

Table 2.

Key Quotations Related to Barriers

Enablers of Abortion Training

1. Program Location

Almost all of the respondents described an NYC location as “pro-choice” and a favorable environment for abortion training. Many residents described a self-selection process; they chose to train at NYC hospitals that offered abortion training. NYC-based abortion training also gave residents, particularly those who plan to relocate after graduation to areas with low abortion access, the ability to provide services.

2. Access to High-Capacity Services

Respondents explained that access to high-volume services provided an available and sustainable training environment. These services were provided within the HHC system or, if there was not enough patient volume available, links were established with freestanding clinics. Residents described how the high volume of cases led to a greater sense of comfort and proficiency. At centers that received referrals for medically complex patients, residents remarked that they benefited by learning how to care for medically complicated patients.

3. Faculty Commitment to Abortion Training

A major theme cited by both leadership and resident respondents was the importance of faculty commitment; the largest impact came from those in leadership positions. Residents also described that abortion providers had the biggest impact on their experience based on their “dedication,” “advocacy,” and “mentorship.” Some residents highlighted that family planning fellowship graduates were familiar with research and added up-to-date patient care approaches.

4. Ryan Program Support

Residency program directors and abortion providers identified external programmatic support from the Ryan Program as an enabler. Many cited how the Ryan Program provided individual programs with a structured curriculum that included learning objectives, highlighted articles, quizzes, and evaluations. Others described how the Ryan Program has technical expertise and experience with improving training within the hospital setting. Partial salary support from the Ryan Program gave abortion trainers additional time to improve the curriculum. Program leadership respondents explained that obtaining support often depended on the presence of a committed abortion provider.

5. Resident Interest

Respondents commented that “word of mouth” among the residents popularized training and led to a decrease in opting out. At one program, an abortion provider described how resident interest ensured an ongoing family planning rotation. At another program resident interest was apparent, but given the lack of other enablers, it was not sufficient to establish routine training.

Barriers to Abortion Training

1. Lack of Program Leadership Continuity

Individual programs experienced leadership changes that hindered training. When abortion providers left, there was inconsistent mentorship available. One HHC attending explained that staff “get burnt out and will leave” because of an unremitting focus on patient volume at NYC public hospitals. Lack of leadership continuity jeopardized enablers such as Ryan Program support.

2. Program Leadership Conflict

Respondents from all levels described conflict between program leaders. At one HHC hospital, the relationship between the HHC chief of service and the affiliated university departmental chair was described as interfering with abortion training, since “the separation of the two to a certain degree has never been what you would call a happy marriage.” A resident at another institution described conflict between a new HHC chief of service and a provider that resulted in relocating second-trimester services to off-site locations where residents do not rotate. Thus, program leadership conflict contributed to decreased access to high-capacity services and training.

3. Lack of Second-Trimester Abortion Services

Participants, particularly residents, spoke about the lack of exposure to second-trimester services as a barrier to comprehensive abortion training. At some programs there were providers who provided limited second-trimester procedures, whereas at others there was no available provider. Low exposure to second-trimester services affected residents' skills, comfort level, understanding of the patient's situation, and ability to provide services following graduation.

4. Difficulty Ordering Mifepristone

Providers mentioned the difficulty of obtaining mifepristone as a key barrier to medication abortion training. HHC leadership ensured that mifepristone was added to hospital formularies, which is the first step in ensuring drug availability. According to respondents, however, mifepristone was not always available for patients because of additional challenges; there were issues related to ordering and meeting certain Food and Drug Administration requirements, and many had to “jump through hoops” to deal with pharmacists who were not familiar with procurement of this medication. Respondents highlighted the concerns about upfront ordering costs and reimbursement rates related to the high cost of mifepristone.

5. Optional Training

Respondents identified a range of abortion training opportunities at NYC public hospitals. The first type of training was routine abortion training, whereby all residents were assigned to participate in abortion services. Those residents who decided to “opt-out” still received training in certain aspects of abortion care based on their individual preferences. In contrast, other programs required residents to “opt-in,” or else they would not receive abortion training. Opt-in abortion training generally occurred on-site but required residents to arrange off-site training for certain aspects of abortion care. None of the opt-in programs had routine exposure to second-trimester abortion training, and most had limited medical abortion exposure. Residents described that having to opt-in, particularly at an off-site location, was challenging given limited elective time. In contrast, programs with routine training facilitated and normalized training.

6. Antiabortion Values of Leadership and/or Staff

All respondents cited examples of personal, religious, and/or political antiabortion values from individuals at all levels within the hospital setting that led to a decrease in the type or frequency of training. These values often acted as an underlying issue for barriers mentioned in this article. They were cited as the primary reason(s) that some residents declined abortion training. Residents often cited examples of resistance to care for patients seeking abortion services from nursing staff members who worked outside of dedicated women's options centers. At certain centers, this form of hostility improved when leadership performed values clarification exercises and instituted opt-out policies.

Discussion

By using a qualitative approach and considering a range of stakeholders, we provided an in-depth overview of the difficult and often complex leadership, professional, and logistic factors required for successful implementation and maintenance of Ob-Gyn abortion training. As specified by the resident participants, optional training is challenging and inconvenient; training programs must find ways to include accessible training opportunities in their curriculum. A key finding in our study was that all 3 programs that provide routine abortion training demonstrated all of the enablers that we listed. Through our interviews and analyses we found that these enablers were mutually reinforcing and, when present, lessened barriers to training. In particular, respondents described how committed faculty members hired by supportive leadership obtained Ryan Program support and fueled resident interest. These committed providers were experienced in all forms of abortion services, which avoided related barriers that we identified in other programs, such as provision of medication abortion and second-trimester services. The impact of these individuals was evident when program leadership changes occurred; in our study, lack of leadership continuity and/or the disappearance of the faculty champion resulted in decreased training.

A limitation of our findings is that we examined abortion training in NYC; most health systems do not operate in such a politically favorable environment. Other systems may not have the backing of prochoice leadership or the financial resources obtained through the Bloomberg abortion training initiative to enact changes in abortion training, limiting generalizability. Our findings, however, are in agreement with other studies conducted throughout the country3,9,10 and are similar to qualitative inquiry related to abortion training in the context of family medicine residency programs.14,15 We would also argue that NYC may represent a “best-case” scenario and that, at a minimum, the enablers and barriers we discovered must be considered. The individual respondents included a high percentage of abortion providers who gave a longitudinal perspective about abortion training in NYC. Although we had a high response rate for the stakeholders, this may represent sampling bias in that most had favorable attitudes toward abortion training. Although we used convenience sampling to recruit residents, which led to incomplete participation, participation was not based on interest in the study; all available residents participated and groups included residents who opted out of abortion training.

We believe that for programs looking to integrate or improve abortion training, having supportive leadership, having a committed and skilled faculty member, and obtaining Ryan Program support are valuable inputs. Most of the abortion providers in our study were trained by the Fellowship in Family Planning, so recruitment of graduates may be beneficial for programs. When these providers obtain Ryan Program support they may benefit from partial salary support and resources to be used toward curriculum development. In addition, the Ryan Program has experience with collaborating with freestanding clinics such as Planned Parenthood, which may be beneficial to programs with limited on-site services.

Conclusion

Despite expectations for routine abortion training, we identified a number of barriers that many Ob-Gyn programs face. The results of our study provide “learning lessons” for individual programs and health systems to consider when initiating or improving abortion training. Supportive leadership, faculty commitment, and external programmatic support from the Ryan Program are key elements to establish Ob-Gyn residency training programs that include routine abortion training.

Footnotes

Maryam Guiahi, MD, MSc, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus; Sahnah Lim, MPH, MIA, and Corey Westover, MPH, are recent graduates from the Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University; Marji Gold, MD, is a Professor in the Department of Family and Social Medicine at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine; and Carolyn L.Westhoff, MD, MSc, is a Professor at the Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, and a Professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Columbia University Medical Center.

Funding: This study was funded by the Fellowship in Family Planning.

This work was presented as a poster abstract at the Reproductive Health Annual Meeting, Las Vegas, NV, September 15–17, 2011, and at the North American Forum on Family Planning Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, October 22–24, 2011.

The authors wish to thank Jenny A. Higgins, MD, Assistant Professor at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health, for her mentorship and advice on qualitative research.

References

- 1.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion No. 424: abortion access and training. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:247–250. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318196426c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/220obstetricsandgynecology01012008.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eastwood KL, Kacmar JE, Steinauer J, Weitzen S, Boardman LA. Abortion training in United States obstetrics and gynecology residency programs. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):303–308. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000224705.79818.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stulberg DB, Dude AM, Dahlquist I, Curlin FA. Abortion provision among practicing obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):609–614. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822ad973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones RK, Kooistra K. Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States, 2008. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43(1):41–50. doi: 10.1363/4304111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Kenneth J. Ryan Residency Training Program in Abortion and Family Planning. http://www.ryanprogram.org. Accessed March 23, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NARAL/NY. Access success: NARAL Pro-Choice New York's residency training initiative success in New York City's public hospitals. http://www.prochoiceny.org/assets/bin/pdfs/accesssucess.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guiahi M, Westover C, Lim S, Westhoff C. The New York City mayoral abortion training initiative at public hospitals. Contraception. 2012;86(5):577–582. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almeling R, Tews L, Dudley S. Abortion training in U.S. obstetrics and gynecology residency programs, 1998. Fam Plann Perspect. 2000;32(6):268–271, 320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sankey HZ, Lewis RS, O'Shea D, Paul M. Enhancing resident training in abortion and contraception through hospital-community partnership. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(3):644–646. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00875-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ipas. Ipas: what we do. http://www.ipas.org/What_We_Do.aspx. Accessed March 23, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strauss AC, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creswell J. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dehlendorf C, Brahmi D, Engel D, Grumbach K, Joffe C, Gold M. Integrating abortion training into family medicine residency programs. Fam Med. 2007;39(5):337–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett I, Aguirre AC, Burg J, Finkel ML, Wolff E, Bowman K, et al. Initiating abortion training in residency programs: issues and obstacles. Fam Med. 2006;38(5):330–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]