Abstract

Background

Pharmacy-based minor ailment schemes (PMASs) have been introduced throughout the UK to reduce the burden of minor ailments on high-cost settings, including general practice and emergency departments.

Aim

This study aimed to explore the effect of PMASs on patient health- and cost-related outcomes; and their impact on general practices.

Design and setting

Community pharmacy-based systematic review.

Method

Standard systematic review methods were used, including searches of electronic databases, and grey literature from 2001 to 2011, imposing no restrictions on language or study design. Reporting was conducted in the form recommended in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and checklist.

Results

Thirty-one evaluations were included from 3308 titles identified. Reconsultation rates in general practice, following an index consultation with a PMAS, ranged from 2.4% to 23.4%. The proportion of patients reporting complete resolution of symptoms after an index PMAS consultation ranged from 68% to 94%. No study included a full economic evaluation. The mean cost per PMAS consultation ranged from £1.44 to £15.90. The total number of consultations and prescribing for minor ailments at general practices often declined following the introduction of PMAS.

Conclusion

Low reconsultation and high symptom-resolution rates suggest that minor ailments are being dealt with appropriately by PMASs. PMAS consultations are less expensive than consultations with GPs. The extent to which these schemes shift demand for management of minor ailments away from high-cost settings has not been fully determined. This evidence suggests that PMASs provide a suitable alternative to general practice consultations. Evidence from economic evaluations is needed to inform the future delivery of PMASs.

Keywords: community pharmacy services, general practice, pharmacy, primary health care, self care

INTRODUCTION

Minor ailments are defined as ‘common or self-limiting or uncomplicated conditions which can be diagnosed and managed without medical intervention’.1–5 Up to 18% of general practice workload is estimated to relate to minor ailments, at a cost of £2 billion annually.6 Similarly, 8% of emergency department consultations involve consultations each year for minor ailments,7 costing the NHS £136 million annually. Research shows that GPs are in favour of diverting the care of minor ailments to other areas of primary care, including community pharmacists.8,9 By reducing the time spent by GPs on managing minor ailments, it would enable them to focus on more complex cases and could reduce patient waiting times.6,8

In the UK, pharmacy-based minor ailment schemes (PMASs) provide public access to NHS treatment and/or advice via a pharmacist or pharmacy personnel, or, where appropriate, to onward referral to other health professionals.10 These schemes were originally proposed by the UK health departments as part of their long-term strategy to encourage patient self-care and utilisation of pharmacies as the first port of call for minor ailments where professional support was required.11,12 The schemes were introduced nationally in all community pharmacies in Scotland and Northern Ireland in 2006 and 2009, respectively.13,14 The Welsh Government will roll out the service nationwide by 2013.15 In England, PMASs are specified as ‘enhanced’ services within the community pharmacy contract, which can be commissioned by the primary care trusts (PCTs) after assessment of local needs.16

A systematic review was conducted to explore the effect of PMASs on patient health and cost-related outcomes. This systematic review also aimed to quantify the extent to which existing PMASs have achieved the aim of shifting demand from high-cost services.

METHOD

Standard systematic review methods were used. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews.17

Data sources and search strategies

The following electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE®, Embase, CINAHL®, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (IPA), National electronic Library for Medicines (NeLM), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), and Centre for Review and Dissemination (CRD), from 2001 to 2011. Supplementary methods included: web-based Google and Google Scholar searches, SCOPUS database for citation searching, reference lists, manual searching of the International Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Royal Pharmaceutical Conference abstracts, and contacts with 109 PCTs in England, as well as local and national health departments/bodies across UK, expert (n = 59) contacts, and a notice in the Pharmaceutical Journal.

How this fits in

Pharmacy-based minor ailment schemes (PMASs) have been introduced across the UK over the last 10 years. Minor ailment consultations in pharmacy are less costly than general practice consultations and provide favourable health-related outcomes. PMASs may redirect care of minor ailments from general practices as intended. The impact of PMASs on general practice workload is difficult to assess.

Inclusion criteria

Types of studies (design, publication status, language)

No restrictions were imposed on study design, country of origin, language, or publication status.

Types of interventions and participants

Only community PMASs offering the management of two or more minor ailments were included. (Note: the acronym PMAS is only used for the purpose of this review, and inclusion was not restricted to this terminology). Where comparisons were made with data from general practice management of minor ailments operating in the same area as the PMAS, these were also included. No restrictions were imposed on the age of study participants.

Types of outcome measures

Evaluations that included the following health and cost-related outcomes were sought: resolution or worsening of symptoms; health-related quality of life; reconsultation with other health professionals; referrals; total costs of PMASs; and mean costs of PMAS consultations. Other outcomes considered included the workload and medicines supplied for minor ailments by general practices operating in the same area as PMASs. The comparative analysis of alternative courses of action, in terms of both their costs and consequences, were also considered; for example, the health-related outcomes of general practice consultation for minor ailments. Any other relevant results from any economic evaluations and costing studies identified were included.18

Data related to patient and stakeholder perspectives of the schemes were included where they were presented alongside health- or cost-related outcome measures.

Exclusion criteria

Evaluations of minor ailment schemes in non-pharmacy settings were excluded.

Data collection and analyses

Independent, duplicate screening of titles, abstracts, and full texts was performed. Independent, duplicate data extraction of each included evaluation was undertaken, using a standard data-extraction form. Disagreements were resolved through discussion among the authors. The Cochrane tool was used to assess the risk of bias.19 The results are presented using a narrative approach, and reported in the form recommended in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement and PRISMA checklist.20

Assessment of quality and risk of bias

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool was used to assess the quality of randomised controlled trials (RCTs).21 For all other study designs, including service evaluations comprising analyses of routinely collected data, surveys, or qualitative research reports, the Review Body for Interventional Procedures (ReBIP) tool was used.22 The Drummond and Jefferson checklist was used to evaluate the quality of any economic evaluations or cost analyses.23

RESULTS

Screening, selection, and included studies

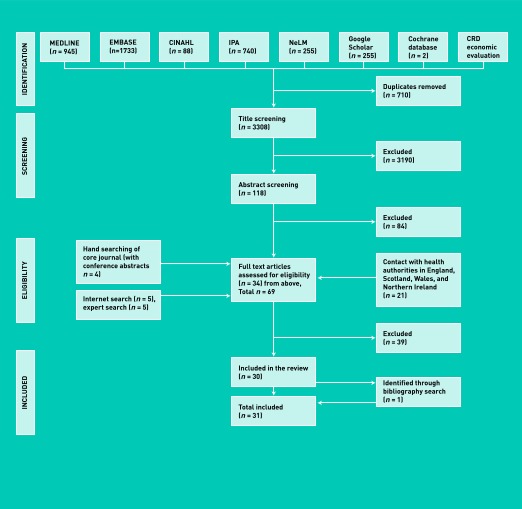

A total of 3308 titles were screened and 31 evaluations fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Thirty-nine papers were excluded after full text screening, owing to: duplicate publication (n = 15); no health or cost-related outcome data reported (n = 12); commentary or news articles (n = 5); evaluation did not involve a PMAS (n = 5); scheme involved only one minor ailment (n = 1); and published outside the inclusion years (n = 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of study-selection process.

All evaluations were conducted in the UK (England n = 28,24–51 Scotland n = 2,52,53 and Wales n = 154) and comprised data from 46 PMASs (Appendix 1: available from the authors).

Only one evaluation was an RCT,54 which evaluated the impact of a PMAS on triaged calls in one general practice in Gwent, Wales. Six evaluations used a before-and-after design,26,38,46,47,50,52 mainly evaluating the impact of the scheme on the number of consultations for minor ailments or on the workload (total number of consultations for all illness types, that is, minor and non-minor) of general practices operating in the same area as the schemes. All other evaluations were classified as ‘service evaluations’ (n = 24).

Quality of reporting and risk of bias

The quality of reporting of the evaluations was often poor. For example, the RCT54 satisfied only two of 10 CASP quality criteria,21 with key information such as the process of randomisation and sample size estimation missing (Appendices 2 and 3: available from the authors). The assessment of the risk of bias was often difficult, owing to inadequate information, such as regarding prespecified outcome measures.

Characteristics of minor ailment schemes

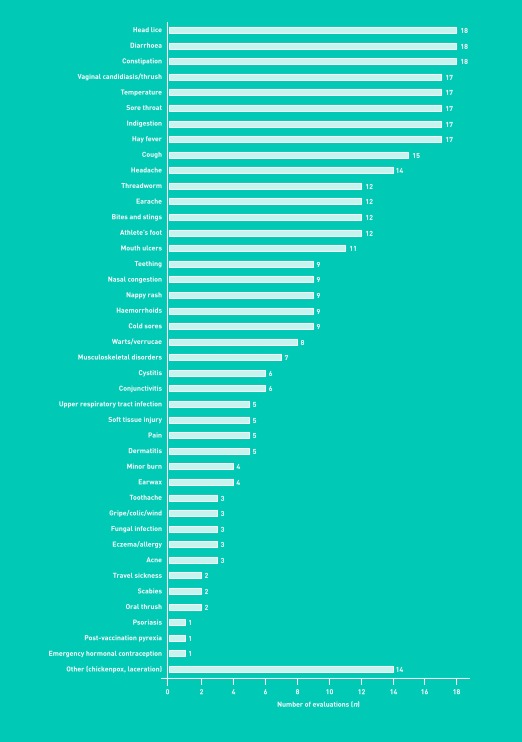

Most evaluations (n = 24) included schemes with patients who were exempt from prescription charges (that is, in countries in which these charges still exist). Where non-exempt patients could access the service, they were required to pay either a prescription charge or medicine cost, whichever was cheaper.25,26,33,38,40,45–47,50 A wide range of conditions was included in most schemes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Minor ailments included in the minor ailments schemes.

Health-related outcomes

The proportion of patients reporting resolution of minor ailments following their index consultation ranged between 68% and 94.4% (Table 1). A 10-fold variation (of 2.4%50 to 23.4%26) was observed with reconsultation rates (that is, consultations with GPs following the index consultation). One evaluation compared reconsultation rates with scheme users and non-users.50 It showed that 2.4% (n = 14) and 3.8% (n = 36) of index consultations with a PMAS and a GP respectively (Table 1) went on to reconsult a GP.

Table 1.

Health-related outcomes of community pharmacy-based minor ailment schemes

| Publication | Patients reporting total resolutions of symptom(s) % (n) | Reconsultation | Referrals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Healthcare professional | Nature of reconsultation | Follow-up duration, days | Reconsultation rate, % (n) | Routine referral to GPs, % (n) | Urgent referral to GPs, % (n) | ||

| Whittington et al, 200150 (scheme users) | Any | Same illness | 14 | 5.7 (33) | Unclear | 3.6 (21)a | |

| GP | Same illness | 14 | 2.4 (14) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Whittington et al, 200150 (general practice users) | Any | Same illness | 14 | 4.0a (38) | |||

| GP | Same illness | 14 | 3.8 (36) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Schafheutle et al, 200252 (Area 1) | 72.3 (47) | Unclear | Same illness | Unclear | 6.2 (4) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Schafheutle et al, 200252 (Area 2) | 68.0 (17) | Any | Same illness | Unclear | 8.0 (2) | 3.0 (16) | 1.0 (5) |

|

| |||||||

| Flint and Rivers, 200349 | 5–30b (unclear) | Unclear | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Magirr, 200348 | GP | Same illness | 14 | 12.0 (6) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Duggan, 200446 | 3.4 (167) | Unclear | |||||

|

| |||||||

| NHS Islington, 200445 | GP | Same illness | 14 | 7.0 (62) | 8.0 (70) | Unclear | |

|

| |||||||

| Parkinson, 200444 | GP | Same illness | Unclear | 19.0 (unclear) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Anonymous, 200543 | GP | Same illness | 14 | 4.0 (130) | ∼4.0 (136) | Unclear | |

|

| |||||||

| Banjo, 200542 | Unclear (7) | Unclear | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Parkinson, 200541 | GP | Unclear | Unclear | 11.0 (unclear) | Unclear | Unclear (9) | |

|

| |||||||

| Proprietary Association of Great Britain and Working in Partnership Programme, 200638 | GP | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear (some) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Gandecha and Butt, 200836 | 15.0 (6) | Unclear | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Gray, 200835 | 86.0 (133) | Any | Same illness | Unclear | 26.7 (unclear) | 5.6 (129) | 0.4 (10) |

|

| |||||||

| Celino and Gray, 200934 | 94.4 (69) | Any | Same illness | Unclear | 4.2 (63) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Davidson et al, 200933 (Area 1) | 1.0 (69) | Unclear | |||||

| Davidson et al, 200933 (Area 2) | 0.7 (16) | Unclear | |||||

|

| |||||||

| NHS Leeds, 200932 | GP | Same illness | Unclear | 13.0 (44) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Mary Seacole Research Centre, 201126 | GP | Same illness | 14 | 23.4 (34) | 1.4 (829) | Unclear | |

|

| |||||||

| GP | Any illness | 14 | 34.5 (50) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Camden Clinical Commissioning Group, 201125 | 1.1 (114) | 0.2 (18) | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Pumtong et al, 201124 | 0.4 (unclear) | Unclear | |||||

All referrals recorded as ‘rapid referrals’.

Data through verbal recall by practice staff. Empty cells: no data were available.

The types of minor ailments associated with reconsultation or referral to other health professionals were explored by six evaluations.26,43–45,48,50 Earache and cough were often associated with referrals and reconsultations in one evaluation.45 Perceived severity of symptoms26 and patient dissatisfaction with the perceived shorter length of treatment available through the PMAS44 were other reasons for reconsultation.

Cost-related outcomes

Most PMASs remunerated participating pharmacies on the basis of a fee per consultation. Where described, fees ranged from £1.50 (price year: 1999/2000)47,50 to £7.85 (price year: 2009).31 Pharmacies were reimbursed for the medicinal items supplied.

A large variation in the mean cost of consultations was observed and ranged from £1.44 (price year: 1999/2000)50 to £15.90 (price year: 2005)43 (Table 2). The variation was due partly to the methods of cost identification, measurement, and valuation, with only pharmacy-related costs tending to be included, for example, consultation fee (remuneration), costs of medicines supplied (that is, reimbursement).

Table 2.

Cost-related data of community pharmacy-based minor ailment schemes

| Publication | Price year | Total number of pharmacies involved in the scheme | Total number of scheme consultations | Total cost (£) of the scheme | Cost measures included in total cost computation | Duration of data collection, months | Scheme mean cost per consultation, £ | Cost measures included in computation of mean cost per consultation |

Mean cost (£) per consultation: other services

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service | Cost (£) | |||||||||

| Anonymous, 200151 | 2000/2001 | 13 | Unclear | 5424.00 | Unclear | Unclear | 5.58 | Consultation fee and medicines supplied | GPa | 10.00 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Whittington et al, 200150 | 1999/2000 | 8 | 576 | 9152.00 | Set-up and running, including administrative, costs | 6 | 1.44 to 1.85b | Pharmacists’ time only | GP | 2.91 to 6.87 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Flint and Rivers, 200349 | 2002 | 12 | 3686 | 12 942.00 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | 6 | 3.51 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Magirr, 200348 | 2002/2003 | 35 | 3073 | 16 015.00 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | 14 | 5.21 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Duggan, 200446 | 2002/2003 | 14 | 4927c | 36 669.96 | Unclear | 16 | 6.88 | Unclear | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| NHS Islington, 200445 | 2004 | 23 | 871 | Unclear | Unclear | 7 | 8.10 | Unclear | GPa | 13.00 |

| GP in walk-in clinicsa | 15.00 | |||||||||

| Practice nursea | 7.00 | |||||||||

| NHS Directa | 15.00 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Parkinson, 200444 | 2003 | 5 | Unclear | Unclear | Consultation fee and medicines costs | 6.10 | Unclear | GPa | 10.42 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Anonymous, 200543 | 2005 | 47 | 3135 | 49 838.72 | Consultation fee, medicines costs, set-up and running administrative costs | 6 | 9.20 to 15.90d | Consultation fee, medicines costs | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Banjo, 200542 | 2004/2005 | 4 | 223 | 1877.99 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | 6 | 8.39 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Parkinson, 200541 | 2003/2004 | 17 | 10 671 | 73 879.00 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | 12 | 6.64 | Unclear | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Horgan and McKieran, 200640 | 2005/2006 | 6 | 1046 | 8412.74 | Consultation fee, medicines costs, and material costs (unclear whether set up or running) | 12 | 8.04 | Consultation fee, medicines costs, and material costs (unclear whether set up or running) | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| NHS City and Hackney, 200639 | 2005/2006 | 46 | 33 494 | 286 181.09 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | 12 | 8.54 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Black, 200837 | 2006/2007 | 38 642 | 228 276.00 | Unclear | 12 | 5.90 | Unclear | Emergency departmenta | 45.00 | |

| 102 | Walk-in centre a | 18.00 | ||||||||

| GPa | 15.00 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Gandecha and Butt, 200836 | 2006/2007 | 19 | 2675 | 15 123.00 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | 14 | 5.65 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | GPa | 11.50 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Gray, 200835,e | 2008 | 2296 | 144 036.00 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | 12 | 6.84 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | GPa | 24.00 | |

| Walk-in centresa | 23.00 | |||||||||

| 14 | NHS Direct telephone calls | 25.00a | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Celino and Gray, 200934 | 2008/2009 | ∼30 | 7113 | 37 000.00 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | 20 | 5.20 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | Minor ailment schemes in other areas | 6.63 |

|

| ||||||||||

| NHS Leeds, 200932 | 2008/2009 | 54 | 26 049 | 136 771.42 | Unclear | 12 | 5.25 | Unclear | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Sewak, 200931 | 2008/0909 | 294 | 308 199 | 1 994 261.00 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | 12 | 6.50 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Baqir et al, 201030 | 2010 | Unclear | Unclear | 4100.00 | Unclear | 1 | Unclear | Unclear | GPa | 36.00 |

| Emergency departmenta | 111.00 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Petrou, 201029 | 2008/2009 | 40 | 20 408 | 122 772.91 | Unclear | 24 | 6.02 | Unclear | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Sim, 201028 | 2009 | Unclear | 1346.40 | Consultation fee | 1 | 3.40 | Consultation fee | GPa | 36.00 | |

| 185 | Emergency departmenta | 111.00 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Baqir et al, 201127 | 2010 | Unclear | 1346.40 | Consultation fee | 1 | 6.03 | Consultation fee and medicines costs | GPa | 36.00 | |

| 185 | Emergency departmenta | 111.00 | ||||||||

| Health visitor | 11.70 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Mary Seacole Research Centre, 201126 | 2009 | 65 | Unclear | 271 961.50 | Unclear | 12 | 4.48 | Unclear | GPa | 21.40 |

Data from reference sources.

Based on average scheme consultation length of 3.19 minutes.

Total number of consultation data refers to 15 months only.

£15.90 with setup and running administrative costs.

Total number of consultation data refers to the total recorded in 6 months from 14 pharmacies, whereas the total cost refers to data from 60 pharmacies collected in 12 months.

One evaluation estimated that savings to the NHS would be £112 million (price year: 2008/2009) for England,31 if all consultations for minor ailments that occur in general practices were undertaken through a PMAS. Such savings were based on the lower mean cost of pharmacy consultations and the assumption that similar health outcomes would be achieved regardless of the settings in which the minor ailments were managed.31

Impact of PMASs on general practice workload

Six evaluations38,47,49,50,52,54 measured the impact of the PMAS on the number of consultations for minor ailments in general practices operating in the same area as the scheme. In Merseyside, England,47,50 the number of GP consultations for minor ailments was significantly lower during the intervention period compared with baseline. However, the total number of GP consultations for all ailments (minor and non-minor) remained unaffected (Table 3). One evaluation reported that the observed decline in the number of consultations for minor ailments at general practices was compensated by the number of minor ailment consultations conducted as part of the pharmacy scheme.52 The impact of a PMAS on the number of practice nurse consultations for minor ailments was reported by one evaluation,38 but the low number of consultations in the control and intervention groups limited the interpretation of these findings (Table 3).

Table 3.

Total number of consultations for minor ailments and all illness types in participating general practices before and after scheme roll out

| Publication | Indicator(s) | Total number of consultations during baseline period, n | Baseline duration, months | Total number of consultations during scheme period,n | Scheme duration, months | Absolute difference Scheme minus baseline, n | Difference scheme minus baseline, % | P-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whittington et al, 200150 | GP consultations for minor ailments | 50a | 4 | 36.5a | 6 | −13.5 | −27.0 | 0.001 |

| All GP consultation types | 560b | 4 | 552b | 6 | −8 | −1.4 | Unclear | |

|

| ||||||||

| Schafheutle et al, 2002 (Area 1)52 | GP consultations for minor ailments | 970 | 3 | 375 | 3 | −595 | −61.3 | Unclear |

| Number of out of hours consultations for minor ailments | 46 | 3 | 0 | 3 | −46 | −100.0 | Unclear | |

|

| ||||||||

| Schafheutle et al, 2002 (Area 2)52 | GP consultations for minor ailments | 235 | 3 | 102 | 3 | −133 | −56.6 | Unclear |

| Number of out of hours consultation for minor ailments | 18 | 3 | 20 | 3 | 2 | 11.1 | Unclear | |

|

| ||||||||

| Flint and Rivers, 200349 | GP consultations for minor ailments | Unclear | 6 | Unclear | 6 | −500b | N/A | Unclear |

|

| ||||||||

| Walker et al, 2003 (control)54 | GP consultations for minor ailments | N/A | N/A | 238 | 2.5 | N/A | N/A | Unclear |

| All GP consultation types | Unclear | Unclear | 560a | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | |

|

| ||||||||

| Walker et al, 2003 (intervention)54 | GP consultations for minor ailments | N/A | N/A | 209 | 2.5 | N/A | N/A | Unclear |

| All GP consultation types | Unclear | Unclear | 504a | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | |

|

| ||||||||

| Bojke et al, 200447 | GP consultations for minor ailments | 37a | 4 | 29a | 6 | −8a | −21.6 | 0.013 |

| All GP consultation types | Unclear | 4 | N/A | 6 | Unclear | Unclear | 0.38 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Proprietary Association of Great Britain and Working in Partnership Programme, 2006 (control group)38 | GP consultations for minor ailments | 33 | 6 | 37 | 6 | 4 | 12.1 | Unclear |

| Nurse consultations for minor ailments | 2 | 6 | 0 | 6 | −2 | −100.0 | Unclear | |

| Telephone consultations for minor ailments | 0 | 6 | 1 | 6 | −1 | N/A | Unclear | |

|

| ||||||||

| Proprietary Association of Great Britain and Working in Partnership Programme, 2006 (intervention group)38 | GP consultations for minor ailments | 30 | 6 | 37 | 6 | 7 | 23.3 | Unclear |

| Nurse consultations for minor ailments | 1 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 10 | 1000.0 | Unclear | |

| Telephone consultations for minor ailments | 5 | 6 | 3 | 6 | −2 | −40.0 | Unclear | |

N/A = not applicable.

Values per week, minor ailments as a proportion of total workload decreased from 8.9% in baseline to 6.6% during intervention period.

Value per month.

The impact of PMASs on the number of medicines supplied by participating general practices for minor ailments (that is, medicines listed in the scheme formulary) was reported in 10 evaluations24,26,36,38,39,45,46,49,50,52 (Appendix 4: available from the authors), most of which showed a decline in prescribing volume when compared with baseline.24,26,38,39,45,46,49,52 A reduction in the number of head lice-related prescriptions was the most noticeable.24,38,45,52 Five evaluations26,45,46,49,50 reported the impact of the schemes on general practice prescribing costs for minor ailments (Appendix 5: available from the authors), with one evaluation showing a decline of 25%.49 However, effect sizes and significance levels were not reported and the evaluations lacked control group comparators.

Patient and stakeholder perspectives

Results from 10 evaluations25,27,28,30–35,52 showed that patients would have used a general practice if no PMAS had been available. Between 47% (patient n = 489)28 and 92% (patient n = unclear)31 of scheme users in these evaluations stated this preference. Buying an over-the-counter medicine was the second choice in the absence of a PMAS. Many evaluations included patient24,26,32,34–36,38,41–45,48–52 and/or stakeholder24,26,32,34–36,38,40,42–46,48–52 attitudes to, and satisfaction with, the scheme. Most evaluations26,32,34–36,38,41,42,45,48–50,52 reported that ≥90% or more user responders were willing to reuse the scheme and expressed general satisfaction with their PMAS consultation, pharmacy staff attitude, and expertise of pharmacy staff in minor ailments management and advice provision. The satisfaction of scheme users was comparable with non-users’ satisfaction with general practice consultations.50

GPs expressed positive attitudes to greater pharmacist participation in the management of minor ailments and the extension of minor ailments included in the schem es.24,26,32,34–36,38,40,42–46,49–51 Two evaluations reported that although the GP participants’ perceived impact on the workload relating to minor ailments was positive, they expressed doubts over whether there was a decline in overall workload, that is, number of daily consultations, following the introduction of a PMAS.50,52

Community pharmacists expressed positive attitudes towards PMASs, with extension of their professional role identified as one of the key benefits of the service.49–52 The workload related to a PMAS was deemed to be accommodated within their routine work.50,52 Patient misuse of the service was often cited as a barrier to efficient service provision.24,26,32,34–36,38,40,42–46,48–52

DISCUSSION

Summary

This is the first systematic review of PMASs that assesses their impact on patient outcomes, costs, and general practice workload.

Data on health-related outcomes were mainly derived from surrogate measures such as reconsultation and referral rates; few studies reported data on resolution of symptoms and none measured changes in quality of life. The observed rates of reconsultation and referral suggest that PMASs reduce consultation rates for minor ailments in general practice. Where comparisons were available, reconsultation rates were reported to be similar for patients who presented in pharmacies compared with those who presented in general practice. Because referral to general practices was an option with most schemes, computation of reconsultation rates should ideally have excluded patients who were referred; however, such exclusion was described in only two evaluations.26,50 The schemes show the potential for contributing to the enhanced access of patients to GP consultations for non-minor ailments, by freeing up the GP workload for minor ailments. Although there was some evidence that general practice prescribing of some medicines included in scheme formularies declined during periods when schemes were operating,49 there were insufficient data to determine whether such reductions resulted in a similar increase in pharmacy supply of those medicines.

The mean consultation costs for scheme users in this review were markedly lower than the mean cost of GP (£36.00; price year: 2008/2009) and emergency department consultations (£111.00; price year: 2008/2009).55

The impact of PMASs on the number of consultations for minor ailments at general practices was more obvious than the impact on the total workload of general practices. The total number of consultations and prescribing for minor ailments at general practices often declined following the introduction of a PMAS. Long-term evaluations are necessary to differentiate between the transient and real impact of these schemes on general practice workload, with regard to both consultations for minor ailments and all consultation types.

Strengths and limitations

This study was conducted according to the standard methods of undertaking a systematic review,19,56 and complies with the PRISMA statement.20 Duplicate screening, selection, data extraction, and quality assessment were undertaken. This minimised errors and bias from the reviewers’ perspective. Despite having no restrictions on language or country of origin, no evaluations of PMASs from outside the UK were identified. The lack of international literature indicates that these schemes might be unique to the UK.

No evaluation was excluded based on the risk of bias or quality. As such, the evidence summarised here needs to be interpreted with caution. The risk of bias associated with either patient outcome or cost was often unclear, owing to the inadequate description of methods. In addition, the lack of full economic evaluation limits the strength of the evidence regarding the cost implications of PMASs. Moreover, those studies that attempted to look at cost-related outcomes often did not assess, or assign a cost to, all potentially related items of resource use.

Implications for research and practice

Future research should aim to assess and report patient outcomes, including health status, resolution of symptoms, and health-related quality of life, and include full economic analyses through RCTs or cohort designs. Owing to the limited duration of minor ailments, opportunistic recruitment strategies are recommended. From the UK perspective, future studies should compare outcomes of minor ailments management in settings such as emergency departments, out-of-hours NHS services, and nurseled minor ailments clinics. Costs from the perspective of both patients and the NHS should be incorporated. Evaluations could focus on specific minor ailments for relevant comparisons of both health- and cost-related outcomes. Future evaluations should: clearly define the services and comparisons made; consider the use of a range of outcome measures of which at least some should be objective (valid and reliable) (see above); include appropriate duration of follow-up to detect important effects on outcomes of interest; provide information on non-responders; and acknowledge and discuss study limitations. Results from high-quality evaluations should be used to inform the strategic direction for the future delivery of PMASs in the UK and beyond.

In terms of practice, funders should endeavour to evaluate existing schemes in regarding effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. The results of the review should provide some reassurance to GPs that patients who seek treatment for their minor ailments via PMASs, are likely to derive benefit from the use of these schemes in terms of symptom resolution and low reconsultation rates. The impact of these schemes on overall GP workload, however, requires further investigation.

Low reconsultation and high symptom-resolution rates suggest that minor ailments are being dealt with appropriately by PMASs. The limited data available from this review suggest that PMAS consultations are less expensive than consultations with GPs. However, those studies that attempted to look at cost-related outcomes often did not assess, or assign a cost to, all potentially related items of resource use. The extent to which these schemes shift demand for minor ailment management away from high-cost settings has not been fully determined. Further economic evaluations are needed to inform the future delivery of PMASs.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following individuals for their contribution: health authorities in the UK and all individuals who contributed to literature relevant to this review and those who responded to the requests; Mr Graham Mowatt, Health Service Research Unit, University of Aberdeen, for advising on quality and the risk of bias assessment procedures and providing the ReBIP tool; the data management team, University of Aberdeen, for assisting with the design and administration of the online data extraction and quality-assessment tool; Mrs Netta Clark and Mrs Hazel Riley for providing administrative support.

Funding

The Pharmacy Practice Research Trust funded this systematic review.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval was required.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Better management of minor ailments: using the pharmacist. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones R, White R, Armstrong D, et al. Managing acute illnesses: an enquiry into the quality of general practice in England. London: The King’s Fund; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Proprietary Association of Great Britain. How to set up a nurse led minor illness management service. http://www.pagb.co.uk/information/howtosetupnurseled.html (accessed 2 May 2013)

- 4.The Self Care Campaign. Self care: an ethical imperative. London: Self Care Campaign; 2010. http://www.selfcareforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Self-Care-An-Ethical-Imperative.pdf (accessed 10 Jun 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scottish Government. Direct supply of medicines in Scotland: evaluation of a pilot scheme--research findings. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government; 2003. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2003/03/16778/20206 (accessed 2 May 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proprietary Association of Great Britain. PAGB annual review. London: PAGB; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bednall R, McRobbie D, Duncan J, Williams D. Identification of patients attending accident and emergency who may be suitable for treatment by a pharmacist. Fam Pract. 2003;20(1):54–57. doi: 10.1093/fampra/20.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris C, Cantrill J, Weiss M. Minor ailment consultations: a mismatch of perceptions. Int J Pharm Pract. 2001;9(suppl):R83. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bayliss E, Rutter P. General practitioners’ views on recent and proposed medicine switches from POM to P. Pharm J. 2004;273:819–821. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellingham C. Introducing the new Scottish contract. Pharm J. 2005;275:637. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Health. Pharmacy in the future: implementing the NHS Plan. London: The Stationery Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scottish Executive Health Department. Our national health: a short guide to the Health Plan. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Northern Ireland Executive. Agreement reached on minor ailments service. Belfast: Northern Ireland Executive; 2008. http://www.northernireland.gov.uk/news/news-dhssps/news-dhssps-december-2008/news-dhssps-231208-agreement-reached-on.htm (accessed 2 May 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scottish Executive. National Health Service (Scotland) ACT 1978 Health board additional pharmaceutical services (Minor Ailment Service) (Scotland) Directions. Edinburgh: Primary Care Division; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffiths L, on behalf of the Welsh Government . Establishment of a National Minor Ailments Scheme in Wales. Cardiff: Welsh Government; 2012. http://www.assemblywales.org/bus-home/bus-business-fourth-assembly-written-ministerial-statements/dat20120307-e.pdf?langoption=3&ttl=Establishment%20of%20a%20National%20Minor%20Ailments%20Scheme%20in%20Wales%20%28PDF%2C%20139KB%29 (accessed 2 May 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. The pharmacy contract. http://www.psnc.org.uk/pages/introduction.html (accessed 2 May 2013).

- 17.Paudyal V, Watson MC, Bond CM, et al. How effective and cost-effective are pharmacy-based minor ailments schemes? A systematic review. PROSPERO. 2011:CRD42011001644. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42011001644 (accessed 2 May 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd edn. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins PT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Version 5.10.March 2011) http://www.cochrane.org/training/cochrane-handbook (accessed 10 Jun 2013).

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:332–336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) http://www.casp-uk.net/ (accessed 2 May 2013).

- 22.Sheffield University and University of Aberdeen. Review Body for Interventional Procedures (ReBIP) http://www.sheffield.ac.uk/scharr/sections/hsr/mcru/other_research/rebip/ (accessed 2 May 2013).

- 23.Drummond M, Jefferson T. Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ. BMJ. 1996;313(7052):275–283. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7052.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pumtong S, Boardman HF, Anderson CW. A multi-method evaluation of the Pharmacy First Minor Ailments scheme. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(3):573–581. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camden Clinical Commissioninig Group. Minor ailments scheme. http://www.camdenccg.nhs.uk/minor-ailments-scheme (accessed 2 May 2013).

- 26.Mary Seacole Research Centre. The Pharmacy First Minor Ailments Scheme in Leicester. Leicester: Mary Seacole Research Centre; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baqir W, Learoyd T, Sim A, Todd A. Cost analysis of a community pharmacy ‘minor ailment scheme’ across three primary care trusts in the North East of England. J Public Health (Oxf) 2011;33(4):551–555. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sim A. An evaluation of the Community Pharmacy Minor Ailment Scheme in North of Tyne. Sunderland: University of Sunderland; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petrou K. Community pharmacy Minor Ailments Scheme. London: NHS Haringey PCT; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baqir W, Todd A, Learoyd T, et al. Cost effectiveness of community pharmacy minor ailment schemes. Int J Pharm Pract. 2010;18:3. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sewak NPS. A cost minimisation analysis of a national minor ailments scheme in community pharmacies in England. London: City University (Thesis); 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.NHS Leeds. Community Pharmacy Minor Ailments Scheme (evaluation) Leeds: NHS Leeds; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davidson M, Bennett S, Cubbin I, Vickers S. An early evaluation of the use made by patients in Cheshire of the pharmacy minor ailments scheme and its cost and impact on patient care. Int J Pharm Pract. 2009;17:B59–B60. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Celino G, Gray N. Evaluation of the Minor Ailment Scheme. Harrow: NHS Calderdale; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gray N. Evaluation of the Bolton ‘Pharmacy First’ Minor Ailments Service. Bolton: Green Line Consulting Limited; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gandecha R, Butt A. Minor Ailments Scheme evaluation. London: Westminster PCT; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Black M. Review of Minor Ailments Scheme (community pharmacy enhanced service) and proposal for future of the service. Sheffield: NHS Sheffield PCT; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Proprietary Association of Great Britain and Working in Partnership Programme. Self care aware: joining up self care in the NHS. London: Proprietary Association of Great Britain; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.NHS City Hackney. Evaluation of pharmacy first Minor Ailments Scheme. London: NHS City and Hackney; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horgan J, McKieran A. Management of minor ailments through community pharmacy. Birmingham: NHS South Birmingham PCT; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parkinson J. Minor ailments schemes can improve patients’ access to treatment and advice. Pharm Pract. 2005. May, pp. 215–217.

- 42.Banjo K. Minor Ailments Scheme — a community pharmacy service to manage self-limiting conditions illnesses in Canvey Island. Rayleigh: NHS Castle Point and Rochford PCT; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anonymous. Minor Ailments Scheme roll out evaluation report. Islington: NHS Islington; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parkinson J. Community pharmacies can treat minor ailments successfully. Pharm Pract. 2004 Jan-Feb;:20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 45.NHS Islington. Islington Minor Ailments Pilot Scheme evaluation report. Islington: NHS Islington; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duggan C. Management of minor ailments in pharmacies: evaluating pilot service development. London: City and Hackney PCT; 2004. ‘Direct care at the pharmacy’. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bojke C, Gravelle H, Hassell K, Whittington Z. Increasing patient choice in primary care: The management of minor ailments. Health Econ. 2004;13(1):73–86. doi: 10.1002/hec.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magirr P. A community pharmacist service to treat minor ailments. Sheffield: NHS Sheffield and Sheffield Local Pharmaceutical Committee; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flint L, Rivers P. Evaluation of the Pharmacy First Scheme provided by the Central Derby Primary Care Trust. Derby: Central Derby PCT; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whittington Z, Hassell K, Cantrill J, Noyce P. A feasibility study comparing community pharmacist and general practice management of minor ailments. Manchester: University of Manchester; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anonymous. Minor ailments trial shows no extra cost to NHS. Chem Drug. 2001;255:5. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schafheutle E, Noyce P, Sheehy C, Jones L. Direct supply of medicines by community pharmacists. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive Central Research Unit; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Information Service Division. Prescribing and medicines: Minor Ailments Service (MAS) Edinburgh: Information Service Division; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walker R, Evans S, Kirkland D. Evaluation of ‘Care at the pharmacy’ in Gwent on the management of self-limiting conditions and workload of a general medical practice. Int J Pharm Pract. 2003;11:R7. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Curtis L. Unit costs of health and social care. Canterbury: University of Kent; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Centre for Review and Dissemination. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York: Centre for Review and Dissemination, University of York; 2009. http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/Systematic_Reviews.pdf (accessed 2 May 2013). [Google Scholar]