Abstract

Background

Sonodynamic therapy (SDT) was developed as a localized ultrasound-activated cytotoxic therapy for cancer. The ability of SDT to destroy target tissues selectively is especially appealing for atherosclerotic plaque, in which selective accumulation of the sonosensitizer, protoporphyrin IX (PpIX), had been demonstrated. Here we investigate the effects of PpIX-mediated SDT on macrophages, which are the main culprit in progression of atherosclerosis.

Methods and results

Cultured THP-1 derived macrophages were incubated with PpIX. Fluorescence microscopy showed that the intracellular PpIX concentration increased with the concentration of PpIX in the incubation medium. MTT assay demonstrated that SDT with PpIX significantly decreased cell viability, and this effect increased with duration of ultrasound exposure and PpIX concentration. PpIX-mediated SDT induced both apoptosis and necrosis, and the maximum apoptosis to necrosis ratio was obtained after SDT with 20 μg/mL PpIX and five minutes of sonication. Production of intracellular singlet oxygen and secondary disruption of the cytoskeleton were also observed after SDT with PpIX.

Conclusion

PpIX-mediated SDT had apoptotic effects on THP-1 macrophages via generation of intracellular singlet oxygen and disruption of the cytoskeleton. PpIX-mediated SDT may be a potential treatment to attenuate progression of atherosclerotic plaque.

Keywords: sonodynamic therapy, protoporphyrin IX, atherosclerotic plaque, macrophage, singlet oxygen, cytoskeleton

Introduction

Sonodynamic therapy (SDT) is a promising noninvasive approach for the treatment of various diseases based on the synergistic effect of low intensity ultrasound and sonosensitization.1–3 The ultrasound energy can be focused on targeted tissues to induce local cytotoxicity by activating sonosensitizers with minimal undesirable damage to healthy tissues.4 The reported cytotoxic mechanisms of SDT include production of reactive oxygen species, especially singlet oxygen (1O2), deleterious effects on the cytoskeleton, and mechanical stress-induced destabilization of the cell membrane.5–8 In addition, the sonodynamic effects depend largely on variation of cell lines, sonosensitizers, and ultrasound parameters.9,10

Over the past 20 years, SDT research has focused primarily and successfully on the treatment of cancer. Some investigations had been carried out using SDT to treat cardiovascular disease in recent years.11 The ability of SDT to destroy target cells selectively is especially appealing for treating atherosclerotic plaque, a localized obstructive process leading to ischemic syndromes.12 We have demonstrated previously the sonodynamic effect of emodin on macrophages,8 which are responsible for progression of atherosclerosis.13,14 However, the exact mechanism involved in the cytotoxic effects of SDT on macrophages is still not clear, and there is little information about other sonosensitizers. Porphyrins or porphyrin-like compounds are the agents of choice in most approaches to SDT, because they can accumulate in rapidly growing tissues, including tumors and atherosclerotic plaques.15,16 Protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) is known to be a component of hematoporphyrin. Our previous research showed that selective accumulation of PpIX in atherosclerotic plaque was 12 times higher than in normal vessel walls,17 indicating the possibility of an atherosclerosis-selective therapeutic agent.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the intracellular accumulation of PpIX, quantify the effect of PpIX-mediated SDT on apoptosis and necrosis of macrophages, and detect intracellular production of singlet oxygen and disruption of the cytoskeleton induced by SDT.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Protoporphyrin IX, 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), and propidium iodide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Fetal bovine serum and RPMI 1640 were obtained from Hyclone Laboratories Inc (Logan, UT, USA). Penicillin-streptomycin was obtained from Beyotime Biotechnology (Jiangsu, People’s Republic of China). An ApoAlert Annexin V-FITC kit was purchased from BD Bioscience (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate was sourced from EMD Biosciences Inc (La Jolla, CA, USA). Sodium azide and 2′–7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) probes were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Jiangsu, People’s Republic of China). A goat polyclonal antibody against α-actin filament was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cells and cell cultures

A human leukemic cell line, THP-1 cell (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA), was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 20 μg/mL penicillin, and 20 μg/mL streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The cells were differentiated into macrophages by adding 100 ng/mL phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate for 72 hours in 35 mm Petri dishes.8

Intracellular PpIX detection

The cells were incubated with different concentrations of PpIX (1–50 μg/mL) for three hours, then stained with 1 μg/mL Hoechst 33342. The cell medium was lightly washed with phosphate-buffered solution twice and observed using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at 405 nm excitation and 630 nm emission wavelengths.

Ultrasonic exposure system

The ultrasonic generator and power amplifier used in this study were assembled by Harbin Institute of Technology (Harbin, People’s Republic of China). The transducer, also made by Harbin Institute of Technology (diameter 3.5 cm, resonance frequency 1.0 MHz, duty factor 10%, repetition frequency 100 Hz), was placed in a water bath and the cells were placed 30 cm away from the transducer. The ultrasonic intensity was 0.5 W/cm2 as measured using a hydrophone (Onda Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). During the sonication procedure, the temperature of the solution inside the Petri dishes increased less than 0.5°C, as measured using a thermometer.

Cell viability assay

Cells were seeded into 35 mm Petri dishes and incubated with different concentrations of PpIX (1–50 μg/mL) for three hours in the dark. They were then exposed to ultrasound for 0–15 minutes. Six hours after SDT, the survival rate of the cells was measured by MTT assay.

Assessment of cell apoptosis and necrosis

Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide

Six hours after SDT with various PpIX concentrations and ultrasound exposure times, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered solution and stained with Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered solution and examined under the fluorescence microscope using a filter with an excitation wavelength of 330–385 nm and an emission wavelength of 420–480 nm. Necrotic cells were stained with red fluorescence while apoptotic cells were stained with blue fluorescence. The percentages of apoptotic and necrotic cells were determined in five random microscopic images with at least 1000 cells/group.

Flow cytometry analysis

An Annexin V-FITC apoptosis kit was used for assessment of cell apoptosis and necrosis by flow cytometry according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were divided randomly into four groups, ie, a control group, an ultrasound alone group, a PpIX only group, and an SDT group. Each group consisted of eight dishes. As a positive control, the cells were exposed to ultraviolet B irradiation for 30 minutes, as described previously,18 to induce apoptosis. Three hours after treatment, the cells were incubated with 5 μL of Annexin V and 5 μL of propidium iodide for 10 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Cells from each sample were then analyzed using a FacsCalibur flow cytometer (BD Bio-sciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The data were analyzed using CELLQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Detection of reactive oxygen species

The intracellular content of reactive oxygen species was determined by measuring the fluorescence intensity of 2′, 7′-dichlorofuorescein (DCF). DCFH-DA was added to the cell medium at a final concentration of 10 μM and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. The cells were then washed carefully twice with phosphate-buffered solution. Immediately after this treatment, all four groups of cells were observed under fluorescence microscopy. A total of 1 × 106 cells were collected and measured using a fluorospectrophotometer (Varian Australia Pty Ltd Melbourne, VIC, Australia) at 488 nm excitation and 525 nm emission wavelengths. In experiments concerning the singlet oxygen scavenger, sodium azide (NaN3), the cells were pretreated with 15 mM NaN3 before exposure to ultrasound. The scavenger at the concentrations used did not cause any significant damage in the cultured cells.

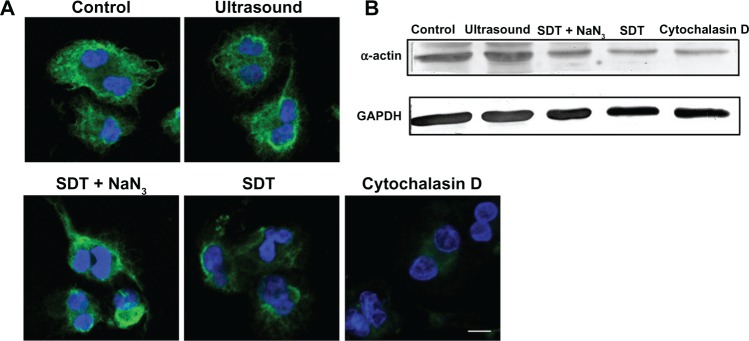

Cytoskeleton analysis

The status of the cytoskeleton in cells of all four groups was assessed by immunofluorescence staining and Western blotting of α-actin. As a positive control, the cells were incubated with 0.1 μg/mL cytochalasin D, which has been confirmed to inhibit polymerization of actin.19 Two hours after treatment, the cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde, then perforated with Triton X-100 to allow exposure of the cytoskeletal actin antibodies to the structures inside. To avoid nonspecific binding of the second antibody, the cells were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin for one hour at room temperature. Primary antibodies were then added for one hour at 37°C. The secondary antibody, conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), was then added for two hours at 37°C. DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) was added for two minutes at room temperature. The cells were then examined under a confocal laser scanning microscopy (FV500, Olympus). Western blot analysis was performed to measure α-actin, as described previously.20 Briefly, two hours after treatment, the cells were collected and prepared for Western blot analysis. The primary antibody was goat polyclonal anti-α-actin antibody (1:500) and the secondary antibody was AP-IgG (1:1000). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as a loading control.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated three times independently. The data are reported as the mean ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance, followed by Student-Newman-Keuls testing, was used to determine any differences between the groups. Statistical evaluation was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (version 13.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Differences with P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

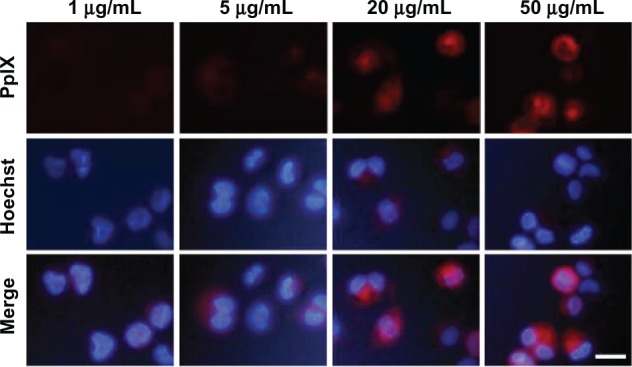

Intracellular accumulation of PpIX

As shown in Figure 1, red PpIX fluorescence was observed in the macrophages after incubation with PpIX for three hours. The PpIX fluorescence distributed diffusely in the cytoplasm surrounding the nucleus. Intracellular PpIX accumulation increased when the cells were cultured with more PpIX (1–50 μg/mL).

Figure 1.

Intracellular accumulation of PpIX. Fluorescent photomicrograph of THP-1 macrophages after three hours of incubation with different concentrations of PpIX (1 μg/mL, 5 μg/mL, 20 μg/mL, and 50 μg/mL). Cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342.

Note: scale bar, 20 μm.

Abbreviation: PpIX, protoporphyrin IX.

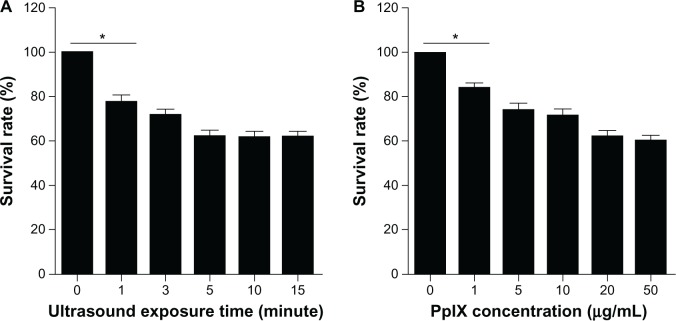

Cell viability after SDT

The survival rate of macrophages decreased with PpIX concentration and duration of ultrasound exposure increased. As shown in Figure 2A, the survival rate decreased significantly from 77.6% ± 3.1% (at one minute) to 62.4% ± 1.8% (at 15 minutes) in cells treated with SDT at a PpIX concentration of 20 μg/mL. The survival rate decreased significantly from 84.4% ± 1.8% (1 μg/mL) to 60.7% ± 2.1% (50 μg/mL) in cells treated with SDT using five minutes of ultrasound irradiation (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Cell viability after SDT. The effect of PpIX-mediated SDT on macrophage viability was assessed by MTT assay. (A) SDT with a PpIX concentration of 20 μg/mL and 1–15 minutes of ultrasound exposure. (B) SDT with five minutes of ultrasound exposure and PpIX concentrations of 1–50 μg/mL.

Notes: Data are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

Abbreviations: MTT, 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; PpIX, protoporphyrin IX; SDT, sonodynamic therapy.

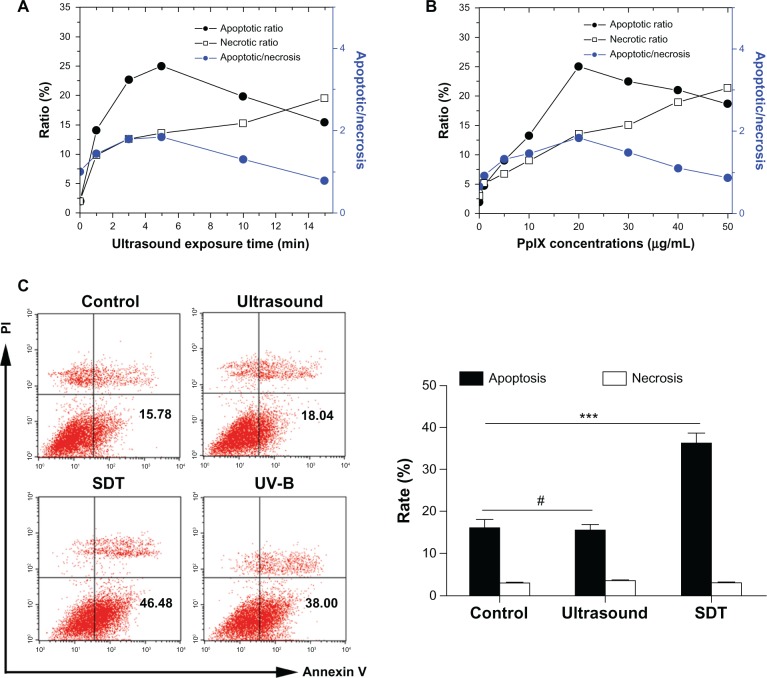

Assessment of apoptosis and necrosis

The results of Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide assays for cell apoptosis and necrosis are shown in Figure 3A and B. Both apoptosis and necrosis were observed in THP-1 macrophages, and the apoptotic ratio was higher than the necrotic ratio under appropriate conditions. At the same time, the necrotic ratio increased gradually as the amount of ultrasound exposure time or/and PpIX concentration increased. The maximum apoptosis/necrosis ratio (1.7 ± 0.3) was observed in cells treated by SDT using 20 μg/mL PpIX and five minutes of exposure to ultrasound. Further, cell apoptosis and necrosis were measured using flow cytometry with double staining of Annexin V and propidium iodide. Cells in the lower right quadrant (Annexin-V+/PI−) represent early apoptotic cells. As shown in Figure 3C, there were a nearly equal cell apoptotic ratio and necrotic ratio in the ultrasound only and control groups. However, the early apoptotic ratio in the SDT and ultraviolet B groups was much higher than that in the other groups.

Figure 3.

Apoptosis and necrosis induced by SDT. The percentages of apoptotic and necrotic THP-1 macrophages after PpIX-mediated SDT were determined by Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide assay (A and B) and flow cytometry with double staining of Annexin V and propidium iodide (C). (A) SDT with identical PpIX concentration (20 μg/mL) and 1–15 minutes of ultrasound exposure. (B) SDT with identical ultrasound exposure time (five minutes) and PpIX concentrations of 1–50 μg/mL. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Apoptosis and necrosis ratio of THP-1 macrophages of the control group and groups treated by ultrasound alone (five minutes), SDT (20 μg/mL PpIX plus five minutes of ultrasound exposure) and ultraviolet B.

Notes: Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 8 per group). #P > 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

Abbreviations: PI, propidium iodide; PpIX, protoporphyrin IX; SD, standard deviation; SDT, sonodynamic therapy; UV-B, ultraviolet B.

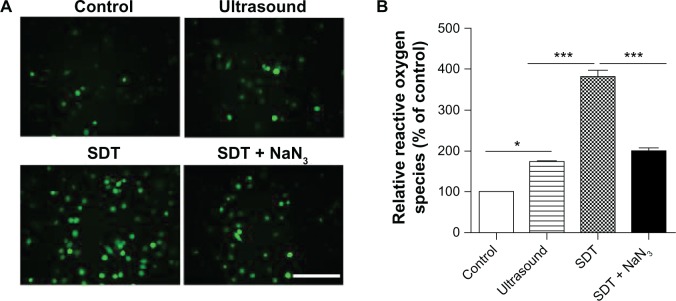

Production of intracellular singlet oxygen after SDT

After confirming induction of apoptosis by SDT, we next examined the possible mechanisms involved. Intracellular formation of reactive oxygen species after SDT was assessed by measuring conversion of nonfluorescent DCFH-DA to fluorescent DCF. DCF fluorescence was monitored by fluorescence microscopy. As shown in Figure 4A, the green fluorescence of DCF was present in a few control cells, but in a small portion of the ultrasound-treated cells and most of the SDT-treated cells. Generation of reactive oxygen species decreased in cells of the SDT group pretreated with the singlet oxygen scavenger, NaN3. The results of fluorospectrophotometry were consistent with those of fluorescence microscopy (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Intracellular ROS production induced by SDT. (A) ROS production in THP-1 macrophages was observed under a fluorescence microscope by DCFH-DA. The SDT-treated cells showed an increased green fluorescence level of ROS in the cytoplasm, and this effect was inhibited by adding NaN3 before sonication. (B) Fluorescence intensity of ROS was measured by fluorospectrophotometry. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Notes: Scale bar, 100 μm. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

Abbreviations: DCFH-DA, 2′–7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate; NaN3, sodium azide; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SDT, sonodynamic therapy.

Cytoskeletal disruption induced by SDT

As shown in Figure 5A, cells in the control group showed normal cytoskeletal morphology with well organized actin filaments surrounding the nucleus. There were no obvious morphologic changes in the cytoskeleton among cells treated by ultrasound alone. Disturbed cytoskeletal filaments were observed in some cells treated with SDT and in most cells treated with cytochalasin D. The filaments surrounding the nuclei were reorganized, with numerous “cross-links” formed, which might have lost their normal function. Normal cytoskeletal morphology was present in cells of the SDT group pretreated with NaN3. Western blot analysis showed that α-actin was decreased in cells from the SDT and cytochalasin D groups. This decrease in the SDT-treated cells was partially inhibited by pretreatment with NaN3 (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Morphologic changes in the intracellular cytoskeleton induced by SDT. (A) Morphologic changes in cytoskeletal α-actin filaments of cells in the control group and groups treated by ultrasound alone, SDT, SDT plus the singlet oxygen scavenger NaN3, and cytochalasin D, evaluated by immunofluorescence staining. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. (B) Protein levels of α-actin in the control group and groups treated by ultrasound alone, SDT, SDT plus NaN3 and cytochalasin D, evaluated by Western blot analysis. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

Note: Scale bar, 20 μm.

Abbreviations: DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; NaN3, sodium azide; SDT, sonodynamic therapy.

Discussion

It is now clear that destabilization and rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque rather than plaque size is the main cause of acute coronary syndromes, and this is largely the consequence of infiltration by macrophages and T lymphocytes in the shoulder region of the plaque and formation of a lipid core.12,21 Given the pivotal role of macrophages in the pathogenesis of vulnerable plaque, several studies have focused on sonodynamic inactivation of such cells to stabilize plaque.

In this study, a dosage-dependent increase in intracellular PpIX fluorescence was observed in macrophages (Figure 1). Previous research concerning the subcellular localization of PpIX has shown that exogenous administration of PpIX mainly distributes in the membranes of cancer cells.22 However, our study of macrophages showed that PpIX distributes diffusely in the cytoplasm. This disparity might arise from the different roles played by macrophages and the previous cancer cell lines used. Unlike highly proliferating cancer cells, macrophages are specialized phagocytic cells expressing scavenger receptors to help engulf foreign substances (including PpIX),23 which might contribute to the diffuse distribution.

Remarkable macrophage death was observed after PpIX-SDT. However, our in vitro study showed that viability of endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells treated with ultrasound plus PpIX at a concentration of 2 μg/mL was not different from that in the control group (treated with neither ultrasound nor PpIX, data not shown). This result indicates that PpIX-SDT kills macrophages effectively while sparing the surrounding vascular cells.

The macrophage survival rate decreased gradually as the duration of ultrasound exposure and PpIX concentration increased. Apoptosis and necrosis have been confirmed to be the predominant forms of cell death in response to SDT for many cells, with the ratio of the two types of dead cells depending on the intensity of treatment. Clinically, apoptosis is preferred over necrosis because it causes fewer inflammatory reactions.24 Several studies has demonstrated that apoptosis of macrophages is associated with smaller plaque size and less lesion progression, while necrosis results in augmentation of the necrotic core and plaque vulnerability.25 Therefore, we intended to identify the optimal therapeutic conditions with the highest apoptosis to necrosis ratio. A series of sonication times and PpIX concentrations were evaluated using Hoechst propidium iodide assays. As shown in Figure 3A and B, at a shorter sonication time and lower dose of sonosensitizer, apoptosis was the main cell death pathway. Longer sonication time or higher PpIX concentration increased the rate of necrosis, eventually making necrosis the main cell death pathway. The highest apoptosis to necrosis ratio was observed after five minutes of ultrasound exposure and a PpIX concentration of 20 μg/mL. Flow cytometry also showed a high apoptosis to necrosis ratio under the same conditions (Figure 3C). Obtaining these optimal experimental parameters is useful in further guidance on clinical application of SDT to cure atherosclerosis and other non-neoplastic diseases involving macrophages.

The cytotoxic mechanisms involved during SDT are numerous, including production of reactive oxygen species secondary to inertial cavitation, mechanical shear stress, and thermal effects, and other mechanisms related to the different ultrasound devices used.2 In this study, the temperature of the cell medium did not increase, which excludes any thermal effects (data not shown). Further, ultrasound alone did not induce significant cell death, excluding any potential effects of mechanical shear stress. Therefore, we focused on the mechanisms of production of reactive oxygen species. As a photosensitizer, PpIX could produce singlet oxygen when acquiring energy from light irradiation.26 However, the role of singlet oxygen production in SDT is still not well defined. As shown in Figure 4A and B, generation of reactive oxygen species in cells treated by ultrasound alone was partially augmented, and this augmentation was greatly enhanced by addition of PpIX. Coincubation with NaN3 significantly attenuated the generation of reactive oxygen species, indicating that PpIX-SDT produced singlet oxygen in macrophages.

Reactive oxygen species play an important roles in physiological and pathological functioning in cells. Excessive intracellular production of singlet oxygen can damage several types of biomacromolecules, including proteins, lipids, and DNA.27 Cytoskeletal proteins consist mainly of microfilaments, microtubules, and intermediate filaments. Their cleavage happens early during apoptosis.28 The deleterious effects of SDT on the cytoskeleton have been documented on a number of studies.8,29 In the present study, disruption of actin filaments was observed in the ultrasound-treated cells, and this disruption was more significant in the PpIX-SDT-treated cells (Figure 5). These findings are consistent with the results of reactive oxygen species and apoptosis assays, suggesting that singlet oxygen contributes to the disorganized actin filament, which is one of the causes of cell apoptosis induced by PpIX-SDT (Figure 6). The precise mechanism by which singlet oxygen is linked to these cytoskeletal events remains to be investigated.

Figure 6.

Schematic summary illustrating the proapoptotic effect of PpIX-SDT on macrophages. Ultrasound activates PpIX in macrophages, resulting in excessive production of intracellular singlet oxygen and subsequent disruption of actin filaments, which initiates cell apoptosis.

Abbreviations: 1O2, singlet oxygen; O2, oxygen; PpIX, protoporphyrin IX; SDT, sonodynamic therapy.

Several studies have reported that removal of macrophages from atherosclerotic plaques could attenuate inflammation and subsequent plaque progression.24,30,31 PpIX-SDT induces apoptosis of macrophages, suggesting a useful and promising treatment for atherosclerosis. However, given that the role of macrophages in the disease process is complicated, further investigations of PpIX-SDT in animal models of atherosclerosis should be performed.

Conclusion

In this study, we identified accumulation of PpIX in macrophages in vitro, and confirmed that optimization of PpIX-SDT could exert cytotoxicity on macrophages by selectively inducing apoptosis with minimal necrosis. Excessive intracellular singlet oxygen production and subsequent disruption of the cytoskeleton were mainly responsible for the cytotoxicity. Our results indicate that, with further proper optimization of the treatment parameters, PpIX-SDT could be useful in the treatment of atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30970786, 81101164, 81171483) and the Scientific and Technical Key Task of Heilongjiang Province, People’s Republic of China (GC10C306). Our research was also supported by a grant from the Funds for Creative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81121003).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this study.

References

- 1.Shibaguchi H, Tsuru H, Kuroki M. Sonodynamic cancer therapy: a non-invasive and repeatable approach using low-intensity ultrasound with a sonosensitizer. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(7):2425–2429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenthal I, Sostaric JZ, Riesz P. Sonodynamic therapy – a review of the synergistic effects of drugs and ultrasound. Ultrason Sonochem. 2004;11(6):349–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lv Y, Fang M, Zheng J, et al. Low-intensity ultrasound combined with 5-aminolevulinic acid administration in the treatment of human tongue squamous carcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;30(2):321–333. doi: 10.1159/000339067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barati AH, Mokhtari-Dizaji M, Mozdarani H, et al. Treatment of murine tumors using dual-frequency ultrasound in an experimental in vivo model. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2009;35(5):756–763. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyoshi N, Igarashi T, Riesz P. Evidence against singlet oxygen formation by sonolysis of aqueous oxygen-saturated solutions of hematoporphyrin and rose bengal. The mechanism of sonodynamic therapy. Ultrason Sonochem. 2000;7(3):121–124. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4177(99)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umemura S, Yumita N, Nishigaki R, Umemura K. Mechanism of cell damage by ultrasound in combination with hematoporphyrin. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1990;81(9):962–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1990.tb02674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Wang P, Zhao P, et al. Apoptosis induced by sonodynamic treatment by protoporphyrin IX on MDA-MB-231 cells. Ultrasonics. 2012;52(4):490–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao Q, Wang F, Guo S, et al. Sonodynamic effect of an anti-inflammatory agent – emodin – on macrophages. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2011;37(9):1478–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2011.05.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song W, Cui H, Zhang R, et al. Apoptosis of SAS cells induced by sonodynamic therapy using 5-aminolevulinic acid sonosensitizer. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(1):39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yumita N, Iwase Y, Nishi K, et al. Sonodynamically-induced antitumor effect of mono-l-aspartyl chlorin e6 (NPe6) Anticancer Res. 2011;31(2):501–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arakawa K, Hagisawa K, Kusano H, et al. Sonodynamic therapy decreased neointimal hyperplasia after stenting in the rabbit iliac artery. Circulation. 2002;105(2):149–151. doi: 10.1161/hc0202.102921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber C, Noels H. Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat Med. 2011;17(11):1410–1422. doi: 10.1038/nm.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore KJ, Tabas I. Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell. 2011;145(3):341–355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiwari RL, Singh V, Barthwal MK. Macrophages: an elusive yet emerging therapeutic target of atherosclerosis. Med Res Rev. 2008;28(4):483–544. doi: 10.1002/med.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang JX, Zhou JW, Chan CF, et al. Comparative studies of the cellular uptake, subcellular localization, and cytotoxic and phototoxic antitumor properties of ruthenium(II)-porphyrin conjugates with different linkers. Bioconjug Chem. 2012;23(8):1623–1638. doi: 10.1021/bc300201h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsiang YN, Crespo MT, Richter AM, et al. In vitro and in vivo uptake of benzoporphyrin derivative into human and miniswine atherosclerotic plaque. Photochem Photobiol. 1993;57(4):670–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1993.tb02935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng C, Li Y, Liang H, et al. Detection and photodynamic therapy of inflamed atherosclerotic plaques in the carotid artery of rabbits. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2011;102(1):26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luchetti F, Canonico B, Curci R, et al. Melatonin prevents apoptosis induced by UV-B treatment in U937 cell line. J Pineal Res. 2006;40(2):158–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casella JF, Flanagan MD, Lin S. Cytochalasin D inhibits actin polymerization and induces depolymerization of actin filaments formed during platelet shape change. Nature. 1981;293(5830):302–305. doi: 10.1038/293302a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desmouliere A, Geinoz A, Gabbiani F, Gabbiani G. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 induces alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in granulation tissue myofibroblasts and in quiescent and growing cultured fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1993;122(1):103–111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2011;473(7347):317–325. doi: 10.1038/nature10146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji Z, Yang G, Vasovic V, et al. Subcellular localization pattern of protoporphyrin IX is an important determinant for its photodynamic efficiency of human carcinoma and normal cell lines. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2006;84(3):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Q, Hamblin MR. Macrophage-targeted photodynamic therapy: scavenger receptor expression and activation state. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2005;18(3):391–402. doi: 10.1177/039463200501800301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinet W, Verheye S, De Meyer GR. Selective depletion of macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques via macrophage-specific initiation of cell death. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2007;17(2):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tabas I. Macrophage death and defective inflammation resolution in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(1):36–46. doi: 10.1038/nri2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, et al. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: an update. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(4):250–281. doi: 10.3322/caac.20114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mates JM. Effects of antioxidant enzymes in the molecular control of reactive oxygen species toxicology. Toxicology. 2000;153(1–3):83–104. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marushige Y, Marushige K. Alterations in focal adhesion and cytoskeletal proteins during apoptosis. Anticancer Res. 1998;18(1A):301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao X, Liu Q, Tang W, et al. Damage effects of protoporphyrin IX – sonodynamic therapy on the cytoskeletal F-actin of Ehrlich ascites carcinoma cells. Ultrason Sonochem. 2009;16(1):50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Croons V, Martinet W, De Meyer GR. Selective removal of macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques as a pharmacological approach for plaque stabilization: benefits versus potential complications. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2010;8(4):495–508. doi: 10.2174/157016110791330816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Meyer I, Martinet W, De Meyer GR. Therapeutic strategies to deplete macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74(2):246–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]