Abstract

Background

In service oriented industries, such as the health care sector, leadership styles have been suggested to influence employee satisfaction as well as outcomes in terms of service delivery. However, how this influence comes into effect has not been widely explored. Absenteeism may be a factor in this association; however, no studies are available on this subject in the mental health care setting, although this setting has been under a lot of strain lately to provide their services at lower costs. This may have an impact on employers, employees, and the delivery of services, and absenteeism due to illness of employees tends to already be rather high in this particular industry. This study explores the association between leadership style, absenteeism, and employee satisfaction in a stressful work environment, namely a post-merger specialty mental health care institution (MHCI) in a country where MHCIs are under governmental pressure to lower their costs (The Netherlands).

Methods

We used a mixed methods design with quantitative as well as qualitative research to explore the association between leadership style, sickness absence rates, and employee satisfaction levels in a specialty MHCI. In depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten key informants and triangulated with documented research and a contrast between four departments provided by a factor analysis of the data from the employee satisfaction surveys and sickness rates. Data was analyzed thematically by means of coding and subsequent exploration of patterns. Data analysis was facilitated by qualitative analysis software.

Results

Quantitative analysis revealed sickness rates of 5.7% in 2010, which is slightly higher than the 5.2% average national sickness rate in The Netherlands in 2010. A general pattern of association between low employee satisfaction, high sickness rates, and transactional leadership style in contrast to transformational leadership style was established. The association could be described best by: (1) communication between the manager and employees; (2) the application of sickness protocols by the managers; and (3) leadership style of the manager.

Conclusion

We conclude that the transformational leadership style is best suited for attaining employee satisfaction, for adequate handling of sickness protocols, and for lower absenteeism, in a post-merger specialty mental health setting.

Keywords: leadership style, transformational leadership, sickness rates, absenteeism, employee satisfaction, qualitative research, specialty mental health care institution

Background

Significance and aim of the study

A large part of the research that has been done concerning employee satisfaction considers job factors such as colleagues, supervisors, training opportunities, and overall satisfaction with the job. Another factor that is often not taken into account is organizational change.1 The study by Howard and Frink1 that addresses the relationship between organizational restructuring and employee satisfaction shows that work turbulence has a negative influence on employee satisfaction. While the satisfaction with growth opportunities and coworkers is important for the motivation of the employees, the satisfaction with the supervisor influences overall job satisfaction. This underscores the importance of the role of supervisors during organizational change and turbulent situations at the workplace.

In recent years, the Dutch health care industry underwent major reform. The main drivers of these changes had been the altering of government policies, reimbursement schemes, and developments in public opinion.2–7 Moreover, the content of the work, ie, the delivery of mental health care, has changed substantially.7 These changes are characterized by the imposition of more administrative duties on the professionals. The reasons for these changes include more healthcare provisions, a more active role of the client, and a shift in quality demands. The latter involves more systematic visitation, registration, and continuing medical education. The new reimbursement system, which is a result of transparency requirements, also places additional bureaucratic weight on the shoulders of the professionals.8

In response to these developments, a large number of mental healthcare institutions (MHCI) merged. In their merged form, the organization has easier access to capital.9 Additionally, MHCIs had to start providing their health care as products, and the managerial influence of people with backgrounds other than health care increased. As a result of the latter, professionals felt a loss of control of their profession.10 Additionally, time management and responsibility became central themes at these mental health institutions.11 Research by Van Sambeek et al10 suggests that these developments require the professional to focus on economical and bureaucratic values, both of which often conflict with their professional values. Furthermore, GGz Nederland, the Dutch association of MHCIs, agreed with the government on extensive cost reductions in the coming years,12 thus putting leaders as well as employees of MHCIs under strain to be as productive as possible.

Therefore, we can presume that the Dutch MHCIs are indeed likely to be an example of turbulent work environments at this time. This makes these institutions a conforming study environment for investigating the influence of leadership on employee satisfaction and absenteeism in a turbulent work place. In general, the aim of the regulatory and organizational changes that occurred in the mental health care sector is the improvement of the quality of the healthcare products offered. However, to what extent this goal is reached in any specific MHCI is at the mercy of the performance of its employees. In turn, employee performance is influenced by their commitment and satisfaction. These are the very same factors that are under pressure due to the transitions of goals, roles, and knowledge. Finally, leadership plays an important role in turbulent situations.13,14 Lane and Down14 suggest that although the role of a leader was perceived to be driving the company’s performance, this has changed to creating a process for sharing the wisdom of many different and contrasting perspectives. This new leadership role can help employees deal with uncertainty and a turbulent working environment.

The individual relationships between leadership style and the three factors (employee satisfaction, absenteeism, and work turbulence) are already described by many researchers and there are clear relationships between the three factors themselves. However, most studies that investigated a combined relationship of these factors assumed a stable work environment. Therefore, the present study will investigate the influence of leadership style on employee satisfaction and absenteeism in a turbulent work environment, namely in a post-merger Dutch MHCI that is under governmental strain for cost reduction. The aim of the study is to explore employee satisfaction and sickness rates in association with the influence of managerial leadership style in the MHCI.

Theoretical background

Absenteeism and employee satisfaction

Several studies show that downsizing or organizational restructuring can lead to decreased job satisfaction, lowered organizational commitment, a higher turnover rate, or increased absenteeism.15 One result of the study by Sagie16 is that organizational commitment and job satisfaction are strongly related to the aggregated duration of voluntary absence of employees. There was, however, no relationship with the duration of involuntary absence. This means that employees who are strongly committed to the organization or highly satisfied with their job show up more often at work than those with low commitment or low satisfaction. Therefore, the relationship between work turbulence and job satisfaction and the relationship between job satisfaction and employee absenteeism can be presumed.

Transactional and transformational leadership style

A person’s leadership style depends largely on their personality.17–25 However, other factors have also been identified. When leadership is examined in an organizational setting, these factors include the organizational structure of the company, its culture, the relevant organizational layer, the means available to the leader, the product that is delivered, and the profile of the employees. Additionally, economical and other external circumstances may have an impact.26–28

It has been stated that the organizational performance and effectiveness of employees may rest from the following three basic pillars: (1) organizational commitment, (2) job satisfaction, and (3) leadership style.25,29–33 Therefore, leadership is both of pivotal importance to organizational success as well as entwined in many internal and external factors. However, the concept of leadership may be simplified using existing categorizations. One of these is the distinction between transactional and transformational leaders.

According to Bass,34 the transactional leadership style is characterized by contingent reward. Employing such a style, the leader gives rewards in exchange for effort and good performance. The transformational leadership style is a more personal style involving charisma, inspiration, intellectual stimulation, individualized consideration, and extensive delegation.34–38 Therefore, the transformational leader motivates people to participate in the process of change and encourages the foundation of a collective identity and efficacy. This eventually leads to stronger feelings of self-worth and self-efficacy among employees. The method through which these feelings are fostered is called empowerment; giving employees authority, responsibility, and accountability for their tasks has a positive effect on their commitment and work satisfaction.37,39–46 Hutchinson and Jackson note in their study that while traditional characteristics of leaders, such as charisma, have always been viewed as important, a new view has emerged that stresses the importance of transparency, humility, and proximity of leaders.47 This new view is in line with the transformational leadership style that emphasizes the importance of the employees. A recent study that focuses specifically on nurses, discussed that relational leadership styles, such as the transformational style, were associated with higher nurse job satisfaction, higher organizational commitment, more staff satisfaction with work, role, work environment, and pay, and higher productivity and effectiveness. In addition, nurses had a greater intention to stay in the organization when the relational leadership style was employed. This is in contrast to the task-focused leadership, such as the transactional style, which scored lower on all the mentioned effects.48 Laschinger et al show similar effects between leadership style and nurses’ satisfaction in their empirical study in Canada.49 Note how the specific leadership style may in this case nurture the other two pillars of organizational performance.

Considering the recent changes in the Dutch mental health care industry, it is worthwhile noting that tensions may exist between the two types of leadership styles discussed earlier. On the one hand, economic and bureaucratic values may pull leaders towards a more industrial model or transactional style. On the other hand, working with employees who are professional experts may invite a transformational style. More specifically, most studies examining transformational and transactional leadership in a health care setting emphasize the need for transformational leadership. Some studies explain that health care today is under a lot of pressure, and that transformational leadership is better suited for such situations.50,51 Others identify positive effects of transformational leadership on the job satisfaction of nurses,52 on an organizational level by a drop in personnel turnover,53,54 and by a decrease in feelings of depersonalization experienced by nursing staff.55 Congruently, Cummings et al56 performed an enquiry into leadership in the general health care sector, more precisely in the nursing workforce and work environment, and concluded that “leadership focused on task completion alone is not sufficient to achieve optimum outcomes. Efforts by organizations and individuals to encourage and develop transformational and relational leadership are needed to enhance nurse satisfaction, recruitment, retention, and healthy work environment.”

Leadership style as a direct influence on absenteeism

Since there is a close relationship between employee satisfaction and absenteeism, it can be assumed there might be a relationship between leadership and absenteeism as well. This relationship has been confirmed by Walumbwa,33 who found that certain leaders demonstrate higher levels of job satisfaction and commitment, and thereby less withdrawal intentions of employees. According to Zhu, Chew, and Spangler,44 specific human resource management practices can have a positive effect on employee performance, motivation, skills, abilities, and knowledge, thus reducing absenteeism. One of the key factors in creating this effect is leadership style.

The study by Tharenou57 showed that leadership style can reduce absenteeism. If an employee receives support from the supervisor, this can provide an environment in which the employee is more likely to attend work.58 Receiving support from a supervisor can be linked to both transactional and transformational leadership styles, depending on the nature of the support. It would fit in the transactional leadership style because these managers control the employees more and will tell them more specifically what to do. It would fit better in the transformational leadership style, however, since these types of managers stimulate the employees to find things out themselves, by still supporting them and guiding them towards the right track. The results of Van Dierendonck58 highly recommend a transformational leadership style; the study suggests that giving employees responsibilities reduces absenteeism.

The direct way in which leadership style affects absenteeism that will be focused on in particular in this study, is the way in which a leader handles the sickness protocols. Boudreau et al59 showed in their study that employees who are less satisfied with their supervisor tend to be absent more. The study showed that sick leave is often simply viewed as additional days off and that it might be the only way for employees to ensure a day off to go to a special event on short notice. Only 15% of the employees participating in their study believed that there was another opportunity for them to get a day off for such purposes. The study tested whether an opportunity for employees to report unscheduled short term absence would reduce the overall sickness rates of the organization and this was confirmed.59 This attitude towards employees, in which they are given the responsibility to report their unscheduled absence instead of calling in sick, is a part of the transformational leadership style. The employees are responsible and have the possibility to report absence on the short term if necessary. This approach resulted in a decrease in absenteeism.

Leadership style as an indirect influence on absenteeism

Besides a direct influence of leadership style on absenteeism through support, a feeling of being over benefited and the handling of sickness protocols, there is clear evidence that employee satisfaction plays an important role in this relationship too. Employees who are more satisfied with their job and their supervisor will be more committed to the organization and call in sick less often. This relationship has been shown by many researchers.25,29,33,39,44,45,56,58

As shown by Howard and Frink,1 satisfaction with the supervisor influences the overall job satisfaction of the employees. Benkhoff60 and Laschinger, Finegan, and Shamian39 show that if employees perceive their supervisor as competent and like their leadership style, they will be more satisfied and committed to the organization. In particular, employee empowerment improves the trust in management and has a positive influence on satisfaction and commitment. Ross and Offermann25 showed a relationship between leadership and employee satisfaction, but found that employee satisfaction does not automatically lead to higher performance. De Veer et al found in their study that nurses with high moral distress levels were less satisfied with their jobs; they report that moral distress could be caused by time pressure, low satisfaction with consultation possibilities within the team, and an instrumental leadership style.61

Zhu et al44 showed that human-capital-enhancing human resource management fully mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and absenteeism and partially mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and organizational outcome.

As described earlier, the transformational leader motivates and encourages people, which leads to stronger feelings of self-worth and self-efficacy among employees, The empowerment of the employees has a positive effect on their commitment and work satisfaction.37,39–45

Visual conceptual framework

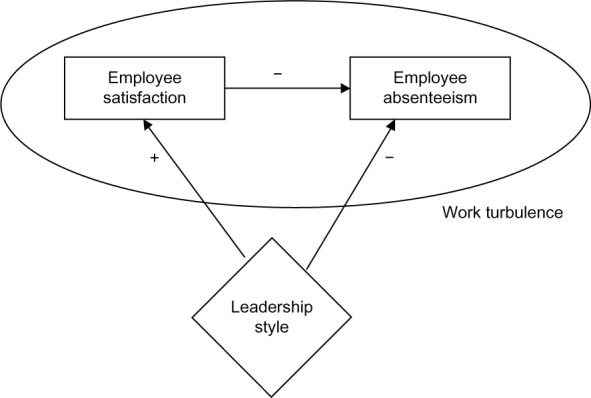

The proposed relationships are shown in Figure 1. The figure shows that leadership style may have a positive association with employee satisfaction and a negative relationship with sickness absence (which means that if a manager has a “better” leadership style, the employee absenteeism decreases), as described above; this is especially the case if the leadership has a transformational style. Based on the above research we formulated the following hypotheses for this study (see below).

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of relationships between leadership style and absenteeism.

Leadership and employee satisfaction

Within a merging organization different work cultures inevitably come together. The ambiguity that discrepancies cause raises the stress that employees experience. Employees feel the need for leadership to steer them through such a changing environment, whilst at the same time involving them in decisions regarding their department and work. If they do not experience such leadership from their management, satisfaction drops. The leadership style of the manager thus influences employee satisfaction, this has to do with the communication between management and employees and the attention that is paid to the needs of the employees.

Therefore, our first hypothesis is that a transformational leadership style is associated with an increase in employee satisfaction because of provided guidance and structure as well as enhancing autonomy of the employees in uncertain situations.

Leadership and employee absenteeism

Employees who feel content and secure will be motivated to provide good quality health services to clients, and consequently show lower absence rates. Conversely, employees that experience changing job descriptions, interventions in the organization, and much uncertainty, will feel less motivation to go to work. Employees who are less satisfied may have a tendency to call in sick more often; thus, this might be an effect of leadership style. Moreover, the way a leader handles sickness protocols may be a direct way by which he influences absenteeism. The sickness protocols influence absenteeism levels and therefore the leadership style can be a direct moderating influence as well as an indirect moderating influence on absenteeism.

Therefore, our second hypothesis is that transformational leadership has a negative relationship with employee absenteeism by handling of sickness protocols.

Methods

Design

We used a mixed methods design with quantitative as well as qualitative research to explore the association between leadership style, sickness absence rates, and employee satisfaction levels in a specialty MHCI.62 In depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten key informants and triangulated with documented research and a contrast between four departments provided by a factor analysis of the data from the employee satisfaction survey and sickness rates available from the human resources department. Data was analyzed thematically by means of coding and subsequent exploration of patterns. Data analysis was facilitated by qualitative analysis software.

Setting

For this study, a MHCI was chosen that recently merged from two smaller institutions in 2009. In 2006, the merger process started by merging two regions (region B and region T) of the MHCI into one. The full legal merger was completed on January 1, 2009.

Sampling

Sickness rates data

Quantitative data on sickness rates of employees in 2010 were obtained from the human resources department in the MHCI by independent researchers (ES, RE, MvB, NB, DS, YZ), between February 9th, 2011 and May 23rd, 2011. Then, sickness rates per department were established. There were seven departments in total.

Employee satisfaction survey

As the merger was believed to have had a severe impact on the employee’s satisfaction, due to the combination of external circumstances and internal organizational change resulting from the merger, the Board wanted to address the resulting burden to the employees. To this end, the Board of the MHCI ordered a qualitative employee satisfaction survey that was performed in 2010 by an independent agency. The outcome of the survey was used to attach values to the measured variables and from this two main variables were deduced: satisfaction with the work and satisfaction with the managers of the departments. These outcomes were used to identify which departments were high and which were low in both forms of employee satisfaction. Determination of comparatively low and high satisfaction rates per department was performed by factor analysis as described below.

Sampling for semi-structured interviews

During the period between February 2011 and May 2011, semi-structured interviews were conducted regarding leadership style in 2010 in the four departments with contrasting sickness rates and satisfaction in order to explore our hypotheses, until saturation of information had occurred, at the level of the Board, directors, managers, and employees. For this purpose, one of two Board members was interviewed, the director of the selected departments was interviewed, and all five managers of the four contrasting departments were interviewed as well. These departments had contrasting sickness rates and levels of satisfaction; managers from departments with low sickness rates and high satisfaction levels were interviewed, as well as managers from departments with high sickness rates and low satisfaction levels. Moreover, the human resources department randomly selected three employees from the contrasting departments. In total, ten persons were interviewed; their interviews were recorded. Also, to validate the contrast between high and low satisfaction on an individual level, during the interviews, we asked several questions regarding the satisfaction of the employees with their managers, from which we could conclude their level of satisfaction, as can be seen in the supplementary materials.

Analysis

The sickness rate data were compared to national sickness rates in the health care setting.62 Departments with high and low sickness rates compared to this national sickness rate were identified. The data of CBS Statline (The Hague, Netherlands) showed that the national sickness rate of the health care sector was 5.2% in 2010. This rate has been compared to the sickness rates data received from the human resources department of GGz Breburg, which means that the total sickness rate of GGz Breburg (5.7%) was directly concluded to be higher than the national rate of 5.2%.

A factor analysis was performed to identify relevant factors in the employee satisfaction survey outcomes. Then, a dimensionality reduction was performed to make a clear overview of the performance of the different departments in terms of high and low satisfaction. The reduction method used is a rotated principle component factor analysis. These results were plotted on a scatter plot with standardized scales in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), from which the high and low satisfaction departments could be identified.

The interviews were analyzed following a method for qualitative research.63,64 In brief, data were analyzed thematically by means of coding and subsequent exploration of patterns. All interviews were analyzed using MAXQDA (VERBI GmbH, Germany).65 We focused on identifying different leadership styles in the contrasting departments. The interview topics can be seen in the supplementary material. The leadership styles of the managers were identified based on the characteristics found in the literature. The leadership styles of the managers were identified by recognizing and asking (implicitly) for leadership style characteristics according to the following criteria:

Top-down communication (transactional) versus bottom-up communication (transformational);

involving the employees in the organization by face to face meetings (transformational) versus by email (transactional);

planning regular face to face meetings with personnel (transformational) versus having an open door policy without active engagement of the employee by the manager (transactional);

engaging employees in the development of new treatments or organisation (transformational) versus updating them on news from the Board (transactional);

providing the opportunity for alternative tasks for sick listed employees (transformational) versus calling the employee to check availability to return to work (transactional).

All interview results were compared and discussed during a group meeting, which lead to clear insights into the leadership styles of the interviewed managers.

Ethical considerations

The employee satisfaction survey was ordered by the Board of the MHCI and performed by an independent research company that provided the outcomes clustered per department to the human resource department on an anonymous basis. Those outcomes were used for the analysis of the satisfaction data. Anonymous sickness rates data clustered by department were provided by the human resource department of the MHCI. The semi-structured interviews were announced by the human resource department and were performed by six independent researchers (ES, RE, MvB, NB, DS, YZ) and without presence of the human resources department. The outcomes were reported anonymously. This approach was approved by the scientific board of the MHCI.

Results

Sickness absence rates in The Netherlands

According to CBS Statline,62 the average sickness rate percentage in The Netherlands in 2010 was 4.2%. Divided in multiple sectors, we find the lowest sickness rates in catering, mineral extraction, and financial institutions and the highest sickness rates in public administration, health care, and education. The sickness rate of the health care sector was 5.2% in 2010. Twenty-five percent of the absenteeism periods that take longer than 7 days have causes of a mental nature and it takes 53 days on average to return to work, but much longer in cases of depressive disorders. According to research by ArboNed the main causes are work pressure and a bad balance between working and private life.66

Sickness absence rates in the MHCI

The average sickness rate of the employees in the MHCI in 2010 was 5.7%, which is higher than average. This was to a great extent due to people who were ill for a long time (43 to 364 days), which accounted for 2.6% of the employees. The seasons of the year seemed to influence the number of employees who are ill for a short time. For an average time period, there is no connection between the number of ill employees and the time of the year. However, the number of employees who were ill for a very long time was low in the beginning of the year and quite constant during the rest of the year.

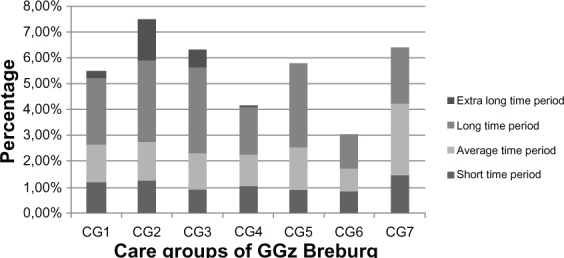

There are seven care groups in the MHCI. Their names and the sickness rates are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sickness absence rates in the care groups of the MHCI split by duration

Abbreviation: MHCI, mental health care institution.

The total percentages of the different care groups vary from 4.0% to 7.5%. The care group with the lowest sickness rate is CG6, the prevention and consultation team. Another care group with a low total sickness rate is CG4: the psychosis and autism care group in T. The care group with the highest sickness rate percentage is CG2 (7.5%), the adults care group; this is remarkably high in comparison to the other care groups.

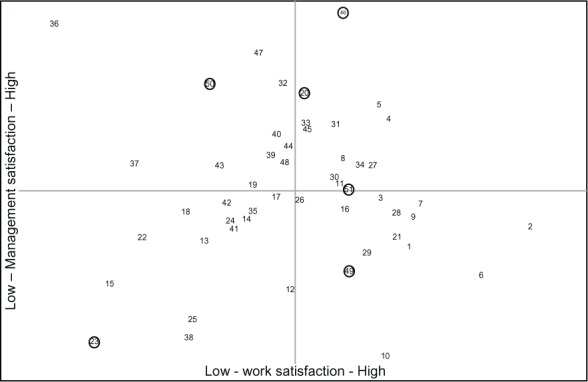

Factor analysis of the employee satisfaction survey

The many variables that our survey was based on were used as a basis for quantitative analysis of the different departments. The number of variables related to satisfaction was rather large (15) and our dataset is rather small (n = 51; [sub] departments). Furthermore, the correlations between the different variables turned out to be very high. Many of these variables measured more or less the same concept. Using principle component factor analysis, only two relevant dimensions remained; namely, work satisfaction and management satisfaction. The former represents employees’ satisfaction with their work, while the latter is a judgment by the employees of the performance of their management. Figure 2 plots the different departments (indicated by numbers) on work and management satisfaction of the employees.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of different departments, indicated by the numbers, on work and management satisfaction, resulting from the satisfaction survey analysis.

Notes: The upper half represents high management satisfaction, the right half corresponds to high work satisfaction. Interviewed departments are circled.

Selection of contrasting departments for interviews

Based on Figure 2, we selected departments with the highest possible contrast between employee satisfaction regarding management satisfaction and work satisfaction, while weighing these for location in B and T (formerly different parts of the institution) for low and high sickness rates, and for low and high employee interdependencies; that is, departments providing outpatient care versus departments providing clinical care. Departments providing inpatient care have higher employee interdependency than outpatient departments. This resulted in the selection of four departments that are marked with a circle in Figure 2. Their characteristics are described in Table 2. Three of the indicated departments in Figure 2, namely numbers 49, 50, and 51 were combined in the table into department D. This consolidation was done because the interviews took place on a higher level than Figure 2 represents. From each department, as a rule, we interviewed both the manager and an employee to compare their points of view and needs. We interviewed two managers from B.

Table 2.

Departments selected for interview

| Reference | Number | Care group | Location | Outpatient/inpatient | Sickness | Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 46 | CG6 | B | Outpatient | Low | M: high W: high |

| B | 23 | CG2 | T | Outpatient | High | M: low W: low |

| C | 20 | CG2 | B | Inpatient | High | M: high W: high |

| D | 49, 50, 51 | CG7 | B and T | Inpatient and outpatient | High | M: high and low W: high and low |

Abbreviations: M, management; W, work.

To make the comparison between the departments more clear, we will call the four departments A, B, C and D. Department A, indicated as number 46 in Figure 2, is a department of the CG6 care group, located in B, providing outpatient health care. This department has a high level of management satisfaction and a high level of work satisfaction. The sickness rates in this care group were the lowest of all care groups, although the sickness rates of employees who were ill for more than one year were high. Overall, this department can be viewed as one of the best departments of all with respect to the factors we compared.

The opposite department is number 23 in the figure, which we will call department B. In this department of the CG2 care group, located in T and providing outpatient health care, the management satisfaction and work satisfaction are low. The sickness rates of the related care group are the highest of all care groups, this department can be viewed as one of the departments that is performing the least well. Department C, indicated with number 20 in Figure 2, is also in the CG2 care group, just as with department B. We chose this department because it has high scores on management satisfaction and work satisfaction, but its care group has the highest sickness rates. In addition, this department is inpatient and located in B. Comparing this department with departments A and B can indicate interesting results or causes of high and low satisfaction and sickness rates.

Finally, department D is indicated by the numbers 49, 50, and 51. These three departments together from the CG7 care group and are closely working together, although the three departments provide both inpatient or outpatient services. We combined them into one department in our analysis. However, the satisfaction rates of the departments varied from relatively low work satisfaction to relatively high work satisfaction and from high management satisfaction to low management satisfaction. The sickness rates of the CG7 care group were high.

The information regarding the four selected departments, concerning the location, type of health care (outpatient/inpatient), sickness rates, and satisfaction rates, is also shown in Table 2. From each department, as indicated in this table, we interviewed both a manager and an employee.

Interview results

The purpose of the interviews was to acquire information from managers and employees of both higher and lower performing departments (based on the graph in Figure 2), in order to compare the outcomes and see if there are differences between these departments. During the interviews, questions were asked about the communication of the manager, the sickness protocols, the attitude of the manager, the leadership style of the manager, and the difference between the cities B and T. The results will be discussed based on these themes. The questionnaire can be found in the supplementary material.

Communication

The leadership and communication styles of the interviewed managers differed. Concerning communicating feedback to the employees, some managers stuck to the official requirement of one individual evaluation meeting per year, whereas others scheduled more meetings. The manager from department A even structurally scheduled a personal meeting every 6 weeks. Also, the nature of communication between managers varied. One particular manager from a low performing department mainly relied on email. However, he added that the door was always open for people to walk in. Not all surprisingly, he admitted that this hardly ever happened. On the other hand, the manager from department A knows a lot about the personal situations of his employees from informal communication and his meetings every 6 weeks. This manager also explained that it was clear very soon whether there was going to be a problem with the numbers (utilization rates) later, because these numbers lag behind the personal knowledge of the individual employee.

In addition, it was considered very important to communicate why specific decisions have been made instead of only communicating what has been decided. The strategic information or decision should be communicated at the same time to all employees to avoid rumor formation.

Leadership

In contrast, some managers relied very much on quantitative data they provided their employees with, such as the productivity they achieved, how much time they spent on patients, etc. Although these numbers were perceived as informative by some employees, the majority felt rather controlled and did not value this type of input. This occurred most evidently when these data were the only way a manager did communicate with his or her employees.

Employees felt that managers should not control or micromanage their employees; they should give them more responsibility and autonomy. Empowerment (shifting important tasks from the manager to the employee) proved to be very important for the employees and seemed to improve satisfaction, as it was applied in high scoring departments.

Relating to the literature, two styles are evident: the transactional and transformational leadership styles. The style that seemingly works best in the MHCI setting is the transformational leadership style, which focuses on the emotional attachment of leader and follower, intellectual stimulation, and motivation to reach the goals of the organization. This implies a lot of personal contact and empowerment. The manager of department A was archetypically such a leader. The transactional leader focuses more on the cost-benefit exchange between the two parties and specifically specifies the performance criteria. Indeed, this is closer to micromanagement and a focus on the numbers. Within the MHCI, the interviewed managers showed different leadership styles, but it was apparent that the transformational leader corresponded to the most satisfied employees and lowest absenteeism (department A). In contrast, the opposite was true for the department with the transactional leader (department B). The leadership styles of the managers differed in terms of the characteristics mentioned in the methods section, ie, a top-down communication style for transactional leaders versus a bottom-up communication style for transformational leaders, looking for alternative tasks for absent employees (if possible) versus calling the absent employee regularly to check the possibility to come back to work, involving employees in the organization by the managers in the weekly staff meeting held by one of the managers to update the staff about the developments and important information (transformational), versus mainly communication via email or quarterly updates (transactional). These results confirm our first hypothesis.

Sickness protocols

The sickness protocol is the same in all departments, but the interpretation of and participation in that process depends per manager. One manager informed us that his approach is to check if employees can do other things than their normal job. So, if someone sprained his ankle or broke something, he might be able to do some paper work and thus still contribute to the work.

We did not find a clear relationship between the sickness protocols and the sickness rates or absenteeism, as the sickness protocols were the same for the whole organization. However, there was a relationship between the leadership style and application of the sickness protocols. Namely, the transformational leader focuses much more on the employee and trusts that he or she will return when ready. So such a leader will call once and leave it to the employee to call in again. The transactional leader will call more often to inform when the employee can come back to work. The transformational leader has a drastically lower absenteeism rate, while the nature of the work is certainly not less stressful (department A). This confirms our second hypothesis.

We also found a difference between the attitude of the employees towards calling in sick between ambulant care groups and clinical care groups or prevention. In the ambulant care groups, employees do not cover work for absent colleagues, which means there is little social pressure and the employees do not feel bad to call in sick. In the clinical care groups and prevention, on the other hand, the employees are interdependent, which might give rise to social pressure and more responsibility. Nevertheless, the transformational manager from department A, which was an outpatient department, had the lowest sickness rates, despite the lack of social pressure to come to work. Apparently, the leadership style had more impact than peer pressure phenomena. This also confirms our hypothesis, but it should be noted that such a strong relation could not be found for the other departments.

Merger

The second theme of the interviews was related to the cultural aspect that played a major role in the merger of the MHCI. Beforehand, we got the impression that B dominated T during the merger and one aim of the interviews was to find out if the managers and employees confirmed this impression. From the analysis of the employee satisfaction survey, we concluded that the B employees were more satisfied with their work and that the T employees were slightly more satisfied with their management. The managers and employees explained the differences between the organizational culture of the MHCI in B and in T as B being more formal and T being more creative. Also, in B, the communication would be more top-down and in T it would be a more bottom-up and transformational style than B.

Discussion

From the sickness rates review, we have concluded that the sickness rate in the MHCI is slightly higher than the national rate. This may be related to the post-merger situation in the MHCI, as was postulated beforehand as organizational upheaval may increase sickness rates and this was the very reason to choose this MHCI for our study.

We did find a correlation between sickness rates, satisfaction, and leadership style. Also, the way that sickness protocols were handled seemed related to leadership style as well as sickness rates. This is a relevant finding as guidelines exist for occupational physicians how to guide sick listed employees back to work.67 This might lead one to expect that resuming work should follow a standardised process based on the guidelines; however, literature shows clearly that this is not what happens in daily practice.68,69 Also, the guidelines and recent research suggest the importance of guiding the managers at the place where the sick listed employee is supposed to resume work toward facilitating a return to work of the employee as well,70 but this has been found not well applicable to occupational physicans.71 Therefore, this study is extremely relevant as it may provide us with the opportunity to diminish sickness absence at the level of managerial leadership style directly.

The analysis of the satisfaction survey and the qualitative interviews confirms our hypotheses concerning employee satisfaction, sickness rate, and leadership style.

Main finding

The main finding of this research was the strong difference in leadership styles in the worst and best performing departments in terms of employee satisfaction and absenteeism. The worst department (department B) had a manager with a clearly identified transactional style, whereas the best department (department A) was managed by a paragon of transformational leadership.

Interpretation

A possible explanation for this result is that the professionals that work at MHCIs were not professionally trained to focus on numbers as work outcome. They focus on wellbeing of and communication with people in their day to day jobs and are intrinsically motivated to do so. Therefore, they feel more comfortable with leaders that do the same. If they are managed too tightly, with a focus on numbers and not people, they will feel disrespected and their satisfaction and intrinsic motivation will drop. Therefore, managers at MHCIs should be transformational leaders, since they focus on this personal development and attachment instead of the numbers, but try to motivate their employees to perform to the benefit of the organization, as a well performing organization is also to the benefit of the patients.

Another interpretation goes beyond the individual level; transformational leadership also predicts team performance. More precisely, this type of leadership promotes team play. This may play a role in the fact that the department with low employee interdependence (department A) and high transformational leadership still had low absenteeism, as the leadership improved interconnectedness of the employees in the outpatient department.

Finally, our results showed that empowerment, a technique often used by transformational leaders, seems to improve employee satisfaction, as it was applied in high scoring departments (departments A, C). The confidence that is instilled in the employees this way can be seen as a reward, which promotes job satisfaction.

The implication of this finding could be that leaders with transactional style should realize the benefits of transformational leadership style and should adopt the latter style, as this style change may have a positive impact on absenteeism and related health aspects of employees. Cummings et al also recommend in their study that managers and administrators should come up with strategies to help leaders to grow and cope with organizational changes by supporting the effectiveness and success of leadership initiatives.72

Strengths

This is the first study exploring the influence of leadership style on employee satisfaction and absenteeism in a turbulent work environment. Interviewing both managers and employees is one of the strengths of the study, as it avoids a one-sided result that might be biased. The interviews were semi-structured and consisted of only open questions. The reason for this format is that we did not want to limit the interviewee’s thoughts by the framing of the question. Also, we wanted to avoid a biased result.

The interviews were conducted following methods of qualitative research, in which a hypothesis was formulated as described earlier. Interviews were conducted, and inclusion for interviews stopped when saturation of information had occurred.73 We followed this method as we wanted to explore aspects of leadership in relation to employee satisfaction and absenteeism. We focused on the contrast between departments, and on the qualitative differences. This does not give the opportunity to provide quantification of findings. However, from the pattern that emerged from the interviews, and from the fact that later interviews did not yield new information, it seemed that theoretical saturation of information had occurred and that our findings are valid.

Limitations

Unfortunately, we could not test for significance of the associations due to the small number of departments. This means that we had to treat each department as a single observation. It was not possible to use a weighing based on the number of respondents per department because the variance of the employee answers was unknown. Consequently, it was only possible to use the departmental differences heuristically.

Implications for practice

Organizations that have to cope with change after a merger may benefit from a transformational leadership style. This may result in better employee satisfaction and lower absenteeism.

Application of sickness protocols from a transformational leadership point of reference may improve absenteeism rates.

Managers should be encouraged to promote empowerment and to use less rigid structures for their employees, to prevent estrangement and depersonalization.

Implications for future research

Further research should aim to quantify the measures of transformational and transactional leadership. Questionnaires should be developed with standard measures for these styles. Further research may help to quantify the problem and the possible impact of improved leadership style.

Conclusion

This study identified an association between leadership style, absenteeism, and employee satisfaction in a MHCI after a merger. Transformational leadership improves employee satisfaction and diminishes absenteeism. As the study is a qualitative study, the association cannot be quantified. However, the findings are of clear practical value and warrant further research.

Interview guide

Questions we asked during our interviews to managers and employees:

Managers

Regarding communication towards employees

Which methods of communication do you use to inform employees?

To what extent do you give strategic information to your employees?

How often do you give strategic information to your employees?

How often do you talk to your employees about other topics (for example work or progress of the company)?

How do you communicate feedback to your employees?

To what extent do you think there are clear work processes in your department?

To what extent do you think your employees are well informed?

To what extent do you think your employees are satisfied about the communication between manager and employees?

Regarding sickness

What is the general sickness protocol in the company?

What is your general attitude towards ill employees?

To what extent do you keep contact with ill employees?

To what extent do you have the feeling that sometimes issues other than illness can play a role for absence that are not communicated by the employee?

What do you do if your employee is sick at home? Will you:

Look for an internal substitute?

Postpone some tasks?

Hire someone else from outside (under what circumstances)?

How can you estimate the direct and indirect costs incurred during these period?

Regarding leadership

Can you describe your own leadership style? (Note: this is a very open question designed to formulate an initial opinion).

To what extent do you feel you have to motivate your employees to do their job? Are they self-motivated? And if they require motivation, how is this accomplished?

To what extent do you emphasize control over your employees?

To what extent do you micromanage your employees?

To what extent do you think B is a different city than T, regarding organizational culture?

Employees

Regarding communication towards managers

Which methods of communication does your manager use to inform you?

To what extent do you receive strategic information from your manager?

How often do you receive strategic information from your manager?

How often do you talk to your manager about other topics (for example work or progress of the company)?

How do you receive feedback from your manager?

To what extent do you think there are clear work processes in your department?

To what extent do you think you have a clear role within the organization?

To what extent do you think you are well informed?

To what extent are you satisfied about the communication between you and your manager?

Regarding sickness

What is the general sickness protocol in the company?

What is your general attitude towards being ill?

What is your threshold between staying home or going to work? (For example, would you stay home with a cold?)

How do you feel when you report sickness rates?

What is the general attitude of your manager towards employees being ill?

How does he/she respond?

To what extent does his/her response influence your own behavior?

To what extent does your manager keep contact with you when you are ill?

Do you think this can motivate you to resume working sooner?

Regarding leadership

Are you satisfied about your relationship with your manager? (Note: this question was asked indirectly as employees are inclined to give socially desirable answers)

To what extent do you feel motivated by your manager?

To what extent does your manager emphasize control over you?

To what extent does your manager micromanage you?

Do you believe that there is a relationship between sickness rates and job satisfaction?

What do you think is the role the manager plays in this?

To what extent do you think B is a different city than T, regarding the organizational culture?

Acknowledgments

The work on this paper was done during the Outreaching Lab “Psychological Aspects of Leadership” by students of the Outreaching Honors Program of Tilburg University, under supervision of Prof Dr Christina van der Feltz-Cornelis.

GGzBreburg, the MHCI under study, ordered the employee satisfaction survey and facilitated the authors for the quantitative and qualitative analysis described in this article. We thank Jan Tromp, MD, Tom van der Schoot, PhD, Lia de Braal MSc, and the other Board members, directors, managers, and employees who participated for their contributions.

Misha van Beek, Daniël Setzpfand, Yu Zhao, and Niko Böehnert (other students from the Outreaching Honors Program of Tilburg University) helped us with the collection of the data between February 9th 2011 and May 23rd 2011 and with the drawing of some initial conclusions. We would like to thank them for their participation.

Footnotes

Disclosure

In the last three years, CFC received royalties for books written on psychiatry. Her employer received a grant for an investigator initiated trial from Eli Lilly. CFC has been an invited speaker for Lilly. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Howard JL, Frink DD. The effects of organizational restructure on employee satisfaction. Group Organ Manage. 1996;21(3):278–303. [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Feltz-Cornelis CM.Ten years of integrated care for mental disorders in The Netherlands Int J Integr Care 2011;11Spec Ede015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Feltz-Cornelis CM. The depression epidemic does not exist. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2009;153:A494. Dutch. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Feltz-Cornelis CM. Towards integrated primary health care for depressive disorder in The Netherlands. The depression initiative. Int J Integr Care. 2009;9:e83. doi: 10.5334/ijic.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Knispel A, Elfeddali I. Treatment of mental disorder in the primary care setting in The Netherlands in the light of the new reimbursement system: a challenge? Int J Integr Care. 2008;8:e56. doi: 10.5334/ijic.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Lyons JS, Huyse FJ, Campos R, Fink P, Slaets JP. Health services research on mental health in primary care. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27(1):1–21. doi: 10.2190/YLPG-RV5E-MCPW-FKTM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landelijke Commissie Geestelijke Volksgezondheid Zorg van Velen. [In Dutch] http://www.psychiatrieweb.mywebhome.nl/pw.spoed/files/docs/lcgv_0202_zorgvanvelen_rapport.pdf

- 8.Naderi PS, Meier BD. Privatization within the Dutch context: a comparison of the health insurance systems of The Netherlands and the United States. Health (London) 2010;14(6):603–618. doi: 10.1177/1363459309360790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sluijs EM, Wagner C. Progress in the implementation of Quality Management in Dutch health care: 1995–2000. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(3):223–234. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzg033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Sambeek N, Tonkens E, Bröer C. Sluipend kwaliteitsverlies in de geestelijke gezondheidszorg. Professionals over de gevolgen van marktwerking. Beleid en Maatschappij. 2011;38(1):47–64. Dutch. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reinders H. The transformation of human services. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2008;52(7):564–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bestuurlijk akkoord toekomst GGZ 2013–2014 Rijksoverheid June182012Available from: http://www.rijksoverheid.nl/ministeries/vws/documenten-en-publicaties/rapporten/2012/06/18/bestuurlijk-akkoord-toekomst-ggz-2013-2014.htmlAccessed April 1, 2013

- 13.Heifetz R, Grashow A, Linsky M. Leadership in a (permanent) crisis. Harvard Bus Rev. 2009;87(7–8):62–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lane DA, Down M. The art of managing for the future: leadership of turbulence. Management Decis. 2010;48(4):512–527. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parker SK, Chmiel N, Wall TD. Work characteristics and employee well-being within a context of strategic downsizing. J Occup Health Psychol. 1997;2(4):289–303. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.2.4.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sagie A. Employee absenteeism, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction: another look. J Vocat Behav. 1998;52:156–171. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yukl G, Lepsinger R. Why integrating the leading and managing roles is essential for organizational effectiveness. Organizational Dynamics. 2005;34(4):361–375. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Judge TA, Bono JE, Ilies R, Gerhardt MW. Personality and leadership: A qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2002;87(4):765–780. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drake RM. A study of leadership. Journal of Personality. 1944;12(4):285–289. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogan R, Curphy GJ, Hogan J. What we know about leadership: Effectiveness and personality. American Psychologist. 1994;49(6):493–504. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.6.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atwater LE, Dionne SD, Avolio B, Camobreco JF, Lau AW. A longitudinal study of the leadership development process: Individual differences predicting leader effectiveness. Human Relations. 1999;52(12):1543–1562. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hogan JC. Personological dynamics of leadership. Journal of Research in Personality. 1978;12(4):390–395. [Google Scholar]

- 23.House RJ, Spangler WD, Woycke J. Personality and charisma in the US presidency: A psychological theory of leader effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1991;36(3):364–396. [Google Scholar]

- 24.House RJ, Howell JM. Personality and charismatic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly. 1992;3(2):81–108. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross SM, Offermann LR. Transformational leaders: measurement of personality attributes and work group performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1997;23(10):1078–1986. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith PB. When elephants fight, the grass gets trampled: The GLOBE and Hofstede projects. Journal of International Business Studies. 2006;37:915–921. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shamir B, Howell JM. Organizational and contextual influences on the emergence and effectiveness of charismatic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly. 1999;10(2):257–283. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masood SA, Dani SS, Burns ND, Blackhouse CJ. Transformational leadership and organizational culture: the situational strength perspective. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture. 2006;220(6):941–949. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lok, Crawford The effect of organisational culture and leadership style on job satisfaction and organisational commitment. Journal of Management Development. 2004;23(4):321–338. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angle HL, Perry JL. An empirical assessment of organizational commitment and organizational. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1981;26(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riketta M. Attitudinal organizational commitment and job performance: a meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2002;23(3):257–266. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howell JM, Frost PJ. A laboratory study of charismatic leadership. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1989;43(2):243–269. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walumbwa FO, Wang P, Lawler JJ, Shi K. The role of collective efficacy in the relations between transformational leadership and work outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2004;77:515–530. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bass BM. From transactional to transformational leadership: learning to share the vision. Organizational Dynamics. 1990;18(3):19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bass BM, Avolio BJ. Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. SAGE; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bass BM, Avolio BJ, Goodheim L. Biography and the assessment of transformational leadership at the world-class level. Journal of Management. 1987;13(7):7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barbuto Jr JE. Motivation and transactional, charismatic, and transformational leadership: A test of antecedents. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies. 2005;11(4):26–40. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Judge TA, Piccolo RF. Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2004;89(5):755–768. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laschinger HKS, Finegan, Shamian The impact of workplace empowerment, organizational trust on staff nurses’ work satisfaction and organizational commitment. Advances in Health Care Management. 2002;3:59–85. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burns JM. Transforming Leadership. Grove Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bass BM, Riggio RE. Transformational Leadership. Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hacker S, Roberts T. Transformational Leadership: Creating Organizations of Meaning. ASQ Quality Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuhnert KW, Lewis P. Transactional and transformational leadership: A constructive/developmental analysis. The Academy of Management Review. 1987;12(4):648–657. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu W, Chew IKH, Spangler WD. CEO transformational leadership and organizational outcomes: The mediating role of human–capital-enhancing human resource management. The Leadership Quarterly. 2005;16:39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walumbwa FO, Hartnell CA. Understanding transformational leadership–employee performance links: The role of relational identification and self-efficacy. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2011;84:153–172. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Munir F, Nielsen K, Garde AH, Albertsen K, Carneiro IG. Mediating the effects of work–life conflict between transformational leadership and health-care workers’ job satisfaction and psychological wellbeing. Journal of Nursing Management. 2012;20:512–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hutchinson M, Jackson D. Transformational leadership in nursing: towards a more critical interpretation. Nursing Inquiry. 2013;20(1):11–22. doi: 10.1111/nin.12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cummings G. Editorial: Your leadership style – how are you working to achieve a preferred future? Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2012;21:3325–3327. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laschinger HKS, Wong CA, Grau AL, Read EA, Pineau Stam LM. The influence of leadership practices and empowerment on Canadian nurse manager outcomes. Journal of Nursing Management. 2011;20:877–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robbins B, Davidhizar R. Transformational leadership in health care today. The Health Care Manager. 2007:234–239. doi: 10.1097/01.HCM.0000285014.26397.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sofarelli D, Brown D. The need for nursing leadership in uncertain times. Journal of Nursing Management. 1998:201–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2834.1998.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nielsen K, Yarker J, Randall R, Munir F. The mediating effects of team and self-efficacy on the relationship between transformational leadership, and job satisfaction and psychological well-being in healthcare professionals: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009:1236–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Casida J, Pinto-Zipp G. Leadership-organizational culture relationship in nursing units of acute care hospitals. Nursing Economics. 2008:7–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reinhardt A. Discourse on the transformational leader metanarrative or finding the right person for the job. Advances in Nursing Science. 2004:21–31. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kanste O, Kyngäs H, Nikkilä J. The relationship between multidimensional leadership and burnout among nursing staff. Journal of Nursing Management. 2007:731–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2934.2006.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cummings GG, MacGregor, Davey, et al. Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work environment: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tharenou P. A test of reciprocal causality for absenteeism. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1993;14(3):269–290. [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Dierendonck D, Le Blanc PM, van Breukelen W. Supervisory behavior, reciprocity and subordinate absenteeism. Leadership and Organization Development Journal. 2002;23(2):84–92. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boudreau CA, Christian WP, Thibadeau SF. Reducing Absenteeism in a Human Service Setting. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 1993;13(2):37–50. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benkhoff B. Disentangling organizational commitment: The dangers of the OCQ for research and policy. Personnel Review. 1997;26(1/2):114–131. [Google Scholar]

- 61.De Veer AJE, Francke AL, Struijs A, Willems DL. Determinants of moral distress in daily nursing practice: A cross sectional correlational questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2013;50:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 2 ed. SAGE; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek Statline.

- 64.Pope C, Mays N, editors. Qualitative Research in Health Care. Second Edition ed. BMJ books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Strauss A, Corbin J, editors. Grounded Theory in Practice. London: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 66.VERBISoftware. Consult. Sozialforschung GmbH; MAXQDA, software for qualitative data analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 67.P&O Actueel Gemiddeld verzuim door psychische klachten is 53 dagen P&O Actueel January242011http://www.penoactueel.nl/agenda/gemiddeld-verzuim-door-psychische-klachten-is-53-dagen-5609.htmlAccessed June 28, 2011

- 68.NVAB NVAB-richtlijnen en procedurele leidraden http://nvab.artsennet.nl/2013Available at: http://nvab.artsennet.nl/Richtlijnen/NVABrichtlijnen-en-procedurele-leidraden.htmAccessed April 1, 2013

- 69.Rebergen DS, Bruinvels DJ, Bezemer PD, Van der Beek AJ, Van Mechelen W. Guideline-Based Care of Common Mental Disorders by Occupational Physicians (CO-OP study): A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2009;51(3):305–312. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181990d32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rebergen DS, Bruinvels DJ, Van Tulder MW, Van der Beek AJ, Van Mechelen W. Cost-Effectiveness of Guideline-Based Care for Workers with Mental Health Problems. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2009;51(3):313–322. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181990d8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.De Vries G, Koeter MWJ, Nabitz U, Hees HL, Schene AH. Return to work after sick leave due to depression; A conceptual analysis based on perspectives of patients, supervisors and occupational physicians. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;136(3):1017–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vlasveld MC, Van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Bültmann U, et al. Predicting return to work in workers with all-cause sickness absence greater than 4 weeks: a prospective cohort study. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2012;22(1):118–126. doi: 10.1007/s10926-011-9326-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cummings GG, Spiers JA, Sharlow J, Germann P, Yurtseven O, Bhatti A. Worklife Improvement and Leadership Development study: A learning experience in leadership development and “planned” organizational change. Health Care Management Review. 2013;38(1):81–93. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e31824589a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]