Abstract

Background

We investigated the heritability and familial aggregation of various indexes of arterial stiffness and wave reflection and we partitioned the phenotypic correlation between these traits into shared genetic and environmental components.

Methods

Using a family-based population sample, we recruited 204 parents (mean age, 51.7 years) and 290 offspring (29.4 years) from the population in Cracow, Poland (62 families), Hechtel-Eksel, Belgium (36), and Pilsen, the Czech Republic (50). We measured peripheral pulse pressure (PPp) sphygmomanometrically at the brachial artery; central pulse pressure (PPc), the peripheral augmentation indexes (PAIxs) and central augmentation indexes (CAIxs) by applanation tonometry at the radial artery; and aortic pulse wave velocity (PWV) by tonometry or ultrasound. In multivariate-adjusted analyses, we used the ASSOC and PROC GENMOD procedures as implemented in SAGE and SAS, respectively.

Results

We found significant heritability for PAIx, CAIx, PPc and mean arterial pressure ranging from 0.37 to 0.41; P ≤ 0.0001. The method of intrafamilial concordance confirmed these results; intrafamilial correlation coefficients were significant for all arterial indexes (r > ≥ 0.12; P < ≤ 0.02) with the exception of PPc (r = −0.007; P = 0.90) in parent–offspring pairs. The sib–sib correlations were also significant for CAIx (r = 0.22; P = 0.001). The genetic correlation between PWV and the other arterial indexes were significant (ρG ≥ 0.29; P < 0.0001). The corresponding environmental correlations were only significantly positive for PPp (ρE = 0.10, P = 0.03).

Conclusion

The observation of significant intrafamilial concordance and heritability of various indexes of arterial stiffness as well as the genetic correlations among arterial phenotypes strongly support the search for shared genetic determinants underlying these traits.

Keywords: arterial stiffness, familial aggregation, heritability, pulse pressure, systolic augmentation

Introduction

Aortic pulse wave velocity (PWV), systolic augmentation and pulse pressure (PP) as measured in central or peripheral arteries are indexes of arterial stiffness and wave reflections. Aortic PWV is a powerful predictor of cardiovascular outcome in the general population [1] as well as in patients with hypertension [2], diabetes, or end-stage renal disease [3]. Similarly, several other indexes of arterial stiffness also predict cardiovascular outcome [4,5], although especially for PP in relation to stroke, the evidence is more equivocal [6].

Understanding to what extent genetic and environmental factors contribute to arterial stiffening is an important issue in view of the relation of arterial properties with outcome. Previous studies included heritability estimates for aortic PWV [7,8], systolic augmentation [9,10] and/or PP [9,11–19]. To our knowledge, however, no previous publication has reported estimates of familial aggregation and the contribution of shared genetic and environmental factors along with the heritability of indexes of arterial stiffness. We addressed this issue in nuclear families recruited from the general population in three European countries in the framework of the European Project on Genes in Hypertension (EPOGH).

Methods

Study population

EPOGH was conducted according to the principles outlined in the Helsinki declaration for investigations in human subjects [20]. The Ethics Committee of each institution approved the protocol. Participants provided their informed written consent. Three EPOGH centers opted to take part in arterial phenotyping. They randomly recruited nuclear families of Caucasian extraction, including offspring with a minimum age of 10 years in Belgium and 18 years in the two other countries. Overall, the response rate was 82%.

We administered a standardized questionnaire to obtain information on each subject’s medical history, smoking and drinking habits, and use of medications. From the type and quality of the alcoholic beverages used, we computed alcohol consumption in grams per day. We defined regular drinking as an alcohol consumption of at least 5 g per day. To exclude consanguinity among families, parents provided a three-generation pedigree. We checked for Mendelian inconsistencies, using the ABO and rhesus blood groups. Our study population consisted of 525 subjects, who underwent arterial measurements. Because the recorded pulse wave was of insufficient quality, we discarded 31 participants from analysis. The 494 participants statistically analyzed were recruited from the population of Cracow, Poland (n = 201), Hechtel-Eksel, Belgium (n = 115), and Pilsen, the Czech Republic (n = 178).

Measurement of blood pressure

The conventional blood pressure (BP) was the average of five consecutive readings obtained at a single home visit. We defined PP as the difference between systolic and diastolic BP. Mean arterial pressure was diastolic pressure and one-third of PP.

Measurement of arterial characteristics

The number of observers involved in the arterial measurements amounted to two in Cracow, and one in Hechtel-Eksel and in Pilsen. To ensure steady state, the arterial measurements were obtained in a quiet examination room, after the subjects had rested for 15 min in the supine position and had refrained from smoking, heavy exercise, and drinking alcohol or caffeinated beverages for at least 2 h prior to the examination.

We recorded the radial arterial waveform during 8 s in the dominant arm by applanation tonometry. We used a high-fidelity SPC-301 micromanometer (Millar Instruments, Inc., Houston, Texas, USA) interfaced with a laptop computer running the SphygmoCor software, version 6.31 (AtCor Medical Pty. Ltd., West Ryde, New South Wales, Australia). We discarded recordings when the systolic or diastolic variability of consecutive waveforms exceeded 10% or when the amplitude of the pulse wave signal was less than 80 mV. We calibrated the pulse wave by measuring BP at the contralateral arm immediately before the recordings. From the radial signal, the SphygmoCor software calculates the central pulse wave by means of a validated [21,22] generalized transfer function. The central pulse pressure (PPc) was the difference between systolic and diastolic BP derived from the aortic pulse wave. The radial augmentation index was defined as the ratio of the second to the first peak of the pressure wave expressed as a percentage. The central augmentation index (CAIx) was the difference between the second and first systolic peak given as a percentage of the aortic PP.

We computed the aortic PWV from recordings of the arterial pressure wave at the carotid and femoral arteries. We measured the distance between the site of the carotid recordings and the suprasternal notch and between the suprasternal notch and the site of the femoral recordings. Aortic PWV was calculated as the ratio of the travel distance in meters to the transit time in seconds. We measured PWV, using the Complior device (Complior, Colson, Les Lilas, France) [23] in Cracow, a pulsed ultrasound wall-tracking system (Wall Track System, Pie Medical, Maastricht, the Netherlands) [24,25] in Hechtel-Eksel, and the SphygmoCor device [26] in Pilsen.

Statistical methods

For database management and statistical analyses, we used the SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA). We compared population means and proportions by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons and the χ2-statistic, respectively. For analyses of heritability and intrafamilial aggregation, we used center-specific standardized distributions. We winsorized the phenotypes under study at the 3% level (1.5% at each end of the distribution) to minimize the influence of outlying data.

Heritability

To estimate heritability, we used a maximum likelihood approach as implemented in the ASSOC procedure of the Statistical Analysis in Genetic Epidemiology (SAGE) package, version 5.1 [27]. We estimated heritability (h2) by assuming multivariate normality after a simultaneously estimated power transformation. ASSOC uses a linear regression model, in which the residual variance is partitioned into the sum of an additive polygenic component and a subject-specific random component. Heritability is the polygenic component divided by the total residual variance [28].

Genetic and environmental correlation

We calculated genetic and environmental correlations between traits after adjusting for covariates as follows. Assuming no dominance variance and no interaction between the genetic and environmental variance components, the variance of a trait is given by: V = G + E, where G is the additive polygenic component and E is the environmental component. The (phenotypic) correlation between two traits (ρP) has both a genetic (ρG) and an environmental (ρE) contribution given by the equation:

where ρG and ρE are the genetic and environmental correlations, respectively. Significance of ρG and ρE suggest that the traits are influenced by shared genes and/or by shared environmental factors [28].

Intrafamilial correlations

We calculated the correlation coefficients between members of the same family as a measure of concordance (positive correlations) or discordance (negative correlation). Hence, in the context of this article, the terms correlation and concordance are used interchangeably. To estimate the intrafamilial correlations, we used generalized estimating equations as implemented in the PROC GENMOD procedure of the SAS package. In these analyses, we adjusted for confounders, we treated pairs of relatives as clusters, and we defined the working correlation matrix as unstructured. Adjustments were cumulative and performed in three steps to check consistency of the parameter estimates, while controlling for an increasing number of variables known to influence arterial stiffness. First, in model 1, we adjusted for center, sex, age, and age-squared. Model 2 also included body height and weight, mean arterial pressure and heart rate (HR) (as appropriate), and antihypertensive treatment. Finally, we considered various lifestyle factors, such as smoking and regular alcohol intake.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Our study population (n = 494) included 204 parents (88 fathers and 116 mothers) and 290 offspring (137 sons and 153 daughters). The number of offspring per family amounted to one in 30 families, two in 102 families, three in 10 families, and more than three in six families. We did not detect any case of consanguinity or Mendelian inconsistency.

Tables 1 and 2 list the characteristic of the participants by generation, center and sex. The mean age of parents and offspring (±SD) was 51.7 ± 6.5 years and 29.4 ± 10.8 years, respectively. In comparison with offspring, parents had higher body mass index and BP, more elevated indexes of arterial stiffness and more frequently used antihypertensive drugs (39.2% versus 4.1%; P < 0.0001). Among parents and offspring, the proportion of smokers was slightly higher in men than in women (31.1% versus 23.0%; P = 0.05). Men also more frequently reported alcohol intake (64.9% versus 30.1%; P < 0.0001). Among smokers, the median daily tobacco consumption was 15 cigarettes [interquantile range (IQR), 10–20] in men and 10 (IQR, 5–20) in women. Among drinkers, the median daily alcohol intake was 20.0 g (IQR, 10.0–31.6) in men and 10.0 grams (IQR, 6.2–18.0) in women.

Table 1.

Characteristics of parents

| Characteristics | Cracow

|

Hechtel-Eksel

|

Pilsen

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers | Mothers | Fathers | Mothers | Fathers | Mothers | |

| Number | 41 | 55 | 10 | 16 | 37 | 45 |

| Age (years) | 50.7 ± 4.5 | 49.9 ± 5.4 | 58.3 ± 11.7† | 57.9 ± 10.6† | 52.2 ± 4.7‡ | 50.6 ± 5.1‡ |

| Height (cm) | 173.6 ± 6.9 | 161.8 ± 5.3*** | 171.3 ± 6.6 | 159.4 ± 8.8** | 178.0 ± 6.2†‡ | 163.3 ± 5.1*** |

| Weight (kg) | 85.2 ± 12.9 | 75.9 ± 14.6** | 83.3 ± 10.2 | 68.6 ± 10.4** | 89.8 ± 10.9 | 74.6 ± 13.9*** |

| HR (bpm) | 71.0 ± 11.7 | 71.6 ± 10.1 | 70.2 ± 12.7 | 66.6 ± 10.1 | 63.5 ± 8.4† | 65.9 ± 10.3† |

| Peripheral hemodynamics | ||||||

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 136.7 ± 18.2 | 136.1 ± 18.0 | 131.3 ± 13.3 | 127.2 ± 15.7 | 129.7 ± 19.1 | 126.8 ± 18.2† |

| Diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 86.6 ± 11.4 | 86.4 ± 9.6 | 81.4 ± 11.8 | 77.3 ± 8.3† | 83.7 ± 11.5 | 78.7 ± 10.2*† |

| MAP (mmHg) | 103.3 ± 13.1 | 103.0 ± 11.8 | 98.1 ± 10.9 | 93.9 ± 9.5† | 99.1 ± 13.4 | 94.8 ± 12.1† |

| PP (mmHg) | 50.1 ± 11.0 | 49.7 ± 11.9 | 49.9 ± 12.3 | 49.9 ± 13.0 | 46.0 ± 11.8 | 48.1 ± 12.2 |

| Augmentation index (%) | 79.6 ± 16.6 | 90.6 ± 15.0** | 69.9 ± 18.2 | 85.0 ± 19.2 | 70.6 ± 19.0 | 85.5 ± 17.4** |

| Central hemodynamics | ||||||

| PP (mmHg) | 37.9 ± 10.6 | 42.5 ± 11.4* | 31.3 ± 5.2 | 38.3 ± 9.1* | 30.8 ± 10.1† | 34.9 ± 11.7† |

| Augmentation index (%) | 133.2 ± 20.3 | 148.8 ± 21.7** | 126.8 ± 21.2 | 148.6 ± 23.2* | 128.3 ± 18.4 | 146.6 ± 20.1*** |

| PWV (m/s) | 10.4 ± 1.4 | 10.6 ± 1.7 | 7.4 ± 1.7† | 7.3 ± 2.7† | 7.0 ± 1.1† | 7.1 ± 1.4† |

Values are arithmetic means ± SD. Peripheral blood pressure was the average of 5 readings at a single home visit. HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PP, pulse pressure; PWV, pulse wave velocity. Significance of the within-center differences between men and women:

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01 and

P < 0.001. Significance of the between-centers differences, by sex, were adjusted for multiple comparisons by Tukey’s test:

P ≤ 0.05 versus Cracow,

P ≤ 0.05 versus Hechtel-Eksel.

Table 2.

Characteristics of offspring

| Characteristics | Cracow

|

Hechtel-Eksel

|

Pilsen

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sons | Daughters | Sons | Daughters | Sons | Daughters | |

| Number | 54 | 51 | 38 | 51 | 45 | 51 |

| Age (years) | 22.8 ± 3.8 | 24.6 ± 5.5 | 38.2 ± 11.2† | 40.5 ± 14.3† | 27.3 ± 5.6†‡ | 25.5 ± 5.5‡ |

| Height (cm) | 178.5 ± 7.2 | 166.2 ± 5.3*** | 175.2 ± 7.3 | 164.6 ± 6.9*** | 179.7 ± 6.1‡ | 166.3 ± 6.0*** |

| Weight (kg) | 72.4 ± 11.4 | 63.9 ± 11.8** | 81.9 ± 14.3† | 65.5 ± 13.0*** | 83.3 ± 14.7† | 63.3 ± 13.3*** |

| HR (bpm) | 71.9 ± 11.2 | 74.2 ± 9.5 | 57.5 ± 9.0† | 63.4 ± 8.4**† | 67.1 ± 9.0†‡ | 70.7 ± 9.6‡ |

| Peripheral hemodynamics | ||||||

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 123.9 ± 12.3 | 113.0 ± 11.8*** | 123.4 ± 8.9 | 118.5 ± 13.5† | 124.8 ± 10.8 | 112.1 ± 9.0***‡ |

| Diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 76.1 ± 9.0 | 71.6 ± 7.1** | 78.1 ± 9.6 | 74.3 ± 10.3 | 77.5 ± 8.6 | 71.3 ± 8.3** |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 92.0 ± 9.0 | 85.4 ± 8.0*** | 93.2 ± 8.7 | 90.0 ± 10.7* | 93.3 ± 8.5 | 84.9 ± 8.0*** |

| PP (mmHg) | 47.8 ± 10.3 | 41.4 ± 8.4** | 45.3 ± 7.7 | 44.2 ± 8.9 | 47.3 ± 8.8 | 40.9 ± 6.4*** |

| Augmentation index (%) | 47.7 ± 15.9 | 59.7 ± 18.8** | 58.3 ± 17.3† | 72.1 ± 21.9**† | 46.6 ± 17.6‡ | 53.7 ± 18.9‡ |

| Central hemodynamics | ||||||

| PP (mmHg) | 28.7 ± 6.6 | 28.8 ± 7.3 | 32.1 ± 5.5† | 31.8 ± 8.7 | 27.1 ± 6.9‡ | 25.2 ± 5.4†‡ |

| Augmentation index (%) | 100.3 ± 11.9 | 113.7 ± 19.5*** | 116.2 ± 20.2† | 130.0 ± 27.3*† | 103.3 ± 19.0‡ | 109.5 ± 20.7‡ |

| PWV (m/s) | 8.7 ± 1.1 | 8.1 ± 1.3* | 6.0 ± 1.3† | 6.0 ± 1.6† | 5.8 ± 0.9† | 5.5 ± 0.9† |

For further explanation, see Table 1. PP, Pulse pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PWV, pulse wave velocity.

Heritability

We adjusted heritability estimates for center, sex, the linear and squared terms of age, body height and weight, mean arterial pressure, HR, antihypertensive treatment, smoking and alcohol intake. We excluded covariates if they were the trait under study. We also did not consider HR as a covariate for peripheral pulse pressure (PPp). For all traits, there were no among-center differences in the polygenic and total variances (F ≤ 3.03; P ≥ 0.05).

Table 3 lists the multivariate-adjusted heritability estimates for the peripheral and central hemodynamic measurements as well as for the anthropometric characteristics. The heritability for PWV was 0.19 (P = 0.08). For all other traits, with the exception of PPc (P = 0.79), heritability was statistically significant (P ≤ 0.0001).

Table 3.

Heritabilities of anthropometric and hemodynamic measurements

| Trait | h2 ± SE | P | Proportion of variance attributable to covariates | λ1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometrics | ||||

| Height | 0.85 ± 0.07 | <0.0001 | 0.54 | 0.82 |

| Weight | 0.54 ± 0.08 | <0.0001 | 0.30 | 0.00 |

| BMI | 0.43 ± 0.09 | <0.0001 | 0.25 | 0.00 |

| Peripheral hemodynamics | ||||

| MAP | 0.39 ± 0.09 | <0.0001 | 0.32 | 0.00 |

| PP | 0.37 ± 0.10 | 0.0001 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| Augmentation index | 0.39 ± 0.10 | 0.0001 | 0.65 | 0.44 |

| Central hemodynamics | ||||

| PP | 0.02 ± 0.08 | 0.79 | 0.31 | 0.15 |

| Augmentation index | 0.41 ± 0.09 | <0.0001 | 0.62 | 0.40 |

| PWV | 0.19 ± 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.42 | 0.00 |

Peripheral BP was the averages of five readings at a single home visit. h2 indicates heritability. λ1 is the power transformation (0 corresponds to log) to normalize the residuals. Anthropometric characteristics were adjusted for center, sex and age. Hemodynamic measurements were adjusted for center, sex, age, age squared, height and weight, antihypertensive treatment, smoking and alcohol intake. In addition, PP, PWV and the augmentation indexes were adjusted for mean arterial pressure and HR. BP, blood pressure; PP, pulse pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PWV, pulse wave velocity.

In further analyses, we included a sibship component of variance, which represents dominance variance and shared environmental factors within sibships. For all phenotypes listed in Table 3, the sibship component did not significantly differ from zero, suggesting no significant departure from an additive genetic model.

Genetic and environmental correlation

In analyses adjusted as before, we studied the genetic and environmental correlations between the hemodynamic phenotypes (Table 4). We excluded PPc because of its low heritability. We observed significant genetic correlations between PWV and the other hemodynamic measurements (0.29 < ρG < 0.49; P < 0.0001), whereas the corresponding environmental correlations were either significantly positive (PPp) or significantly negative (CAIx) or not significant [peripheral augmentation index (PAIx)].

Table 4.

Genetic and environmental correlations between hemodynamic phenotypes

| PWV

|

CAIx

|

PAIx

|

PPp

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρG | P | ρG | P | ρG | P | ρG | P | |

| Genetic correlation | ||||||||

| CAIx | 0.443 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| PAIx | 0.433 | <0.0001 | 0.952 | <0.0001 | ||||

| PPp | 0.298 | <0.0001 | 0.097 | 0.031 | 0.075 | 0.096 | ||

| MAP | 0.489 | <0.0001 | 0.105 | 0.020 | 0.084 | 0.063 | −0.080 | 0.076 |

| ρE | P | ρE | P | ρE | P | ρE | P | |

|

| ||||||||

| Environmental correlation | ||||||||

| CAIx | −0.105 | 0.020 | ||||||

| PAIx | −0.042 | 0.353 | 0.786 | <0.0001 | ||||

| PPp | 0.098 | 0.030 | 0.030 | 0.507 | 0.042 | 0.353 | ||

| MAP | −0.039 | 0.389 | 0.010 | 0.825 | −0.020 | 0.658 | 0.036 | 0.426 |

Peripheral BP was the averages of five readings at a single home visit. CAIx, central augmentation index; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PAIx, peripheral augmentation index; PPp, peripheral pulse pressure.

Intrafamilial correlation coefficients

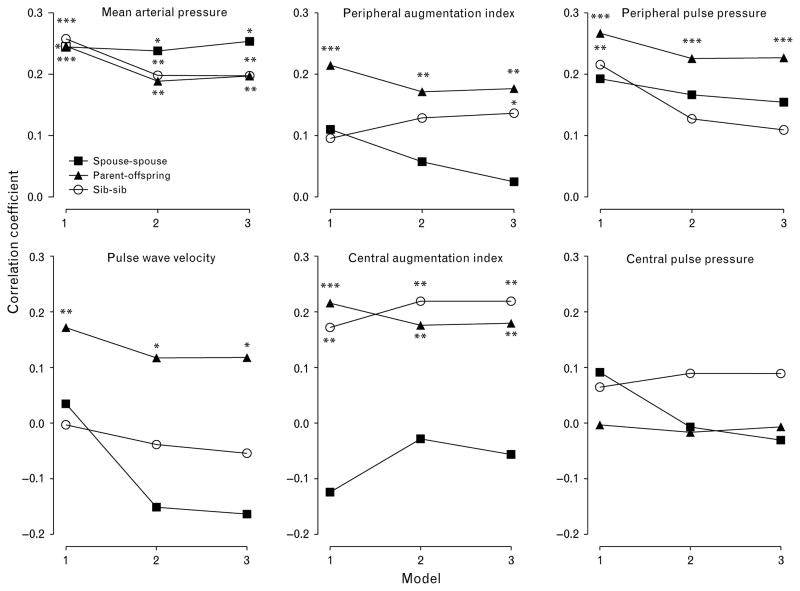

In parent–offspring pairs, the multivariate-adjusted intrafamilial correlation coefficients were significant for all traits with the exception of PPc, irrespective of the level of adjustment. This was also the case for the correlation coefficients for mean arterial pressure and the CAIx in sib–sib pairs. In spouse–spouse pairs, the only significant intrafamilial correlation was for mean arterial pressure (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Intrafamilial correlation coefficients. Model 1 is adjusted for center, sex, and age (linear and squared terms). The two other models reflect further cumulative adjustments for height and weight, mean arterial pressure, heart rate (HR) (if applicable) and antihypertensive treatment (model 2), and, in addition, for lifestyle factors such as smoking and alcohol intake (model 3). Significance of the intraclass correlation coefficients: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

With adjustments applied for center, sex and age, the intrafamilial correlations for body height were 0.50 in parent–offspring pairs, 0.46 in sib–sib pairs, and 0.37 in spouse–spouse pairs. The corresponding correlation coefficients for body weight were 0.24, 0.46 and 0.38 and those for body mass index were 0.19, 0.30 and 0.30, respectively (P ≤ 0.006 for all intrafamilial correlations of anthropometric measurements).

Discussion

We investigated several indexes of arterial stiffness within families. We estimated in the same subjects familial aggregation, heritability, and the contribution of shared genetic and environmental factors. We found significant intrafamilial concordance in parent–offspring pairs for aortic PWV, peripheral and central systolic augmentation, and PPp. In addition, the estimates of heritability for the aforementioned traits ranged from 0.19 for PWV to 0.41 for the CAIx. The genetic correlations of PWV with the systolic augmentation indexes and PPp were significant, whereas the corresponding environmental correlations were only significantly positive for PPp. Our findings suggest that common genes influence arterial stiffness. A shared environment, over and beyond the lifestyle factors for which we accounted, apparently plays only a minor role in the familial aggregation of these traits. In our hands, covariates explained 42% of the variance of PWV, which experts consider as the gold standard to quantify arterial stiffness [29].

In analyses adjusted for the linear and squared terms of age, body weight, and height, the heritability of the carotid-femoral PWV was 0.40 among 817 pedigrees in the Framingham Heart Study [7]. With adjustments applied for sex and age, the heritability of carotid-femoral PWV was 0.36 in a single extended pedigree recruited in the framework of Erasmus Rucphen Family Study [8]. With additional adjustments for mean arterial pressure, HR, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and blood glucose, the estimate was 0.26. Heritability estimates of PWV in previous studies [7,8] tended to be larger than our current estimate, probably because we adjusted for more covariates. Indeed, when we only accounted for center, sex and age, the heritability of PWV was 0.30 (P = 0.0021).

Two studies reported on the heritability of the central systolic augmentation index. Among 225 monozygotic and 594 dizygotic female twin pairs, the heritability of the augmentation index was 0.37 in analyses adjusted for age, height, mean arterial pressure and HR [9]. In 32 extended families, the heritability of the augmentation index was 0.18 with cumulative adjustments for anthropometric characteristics, hypertension, diabetes and cholesterol [10]. In the current study, the multivariate-adjusted heritabilities for the central and PAIxs were 0.41 and 0.37, respectively. In general, heritability estimates from family-based studies tend to be lower than those from twin studies. It remains unclear to what extent differences in recording techniques, the number of observers involved in the measurement, reproducibility, or adjustment for confounders explain the variability across studies in the heritability estimates for systolic augmentation. In our hands, the intraobserver and interobserver coefficients of variation across the three centers were less than 2.76% and 5.30%, respectively [30].

Several studies investigated the heritability of the PPp. The adjusted heritability estimate was 0.13 in a study of white female twin pairs with wide age range (18–73 years) [9]. In young twins (10–26 years), the heritability of PPp was similar among European and African Americans and averaged 0.53 with adjustments applied for ethnicity, sex, age, BMI, and their interactions [11]. In family-based studies, in Blacks [12–14], whites [12,15–17], and other ethnicities [12,18,19], the multivariate-adjusted heritability of PPp ranged from 0.13 to 0.51.

To our knowledge, only one previous study reported on the heritability of PPc as extrapolated from the tonometrically registered PP calibrated on the basis of the oscillometrically measured brachial BP [7]. The heritability of the PPc, adjusted for age, age squared, height, and weight was 0.35 [7], whereas in our current analysis it was zero both with minimal adjustment for center, sex, and age (h2 = 0.02) and after additional cumulative adjustment for anthropometric characteristics, mean arterial pressure, HR, smoking, alcohol intake, and use of antihypertensive medication (h2 = 0.02). We analyzed the pulse wave at the radial artery to assess PPc. Such an approach may have led to a small degree of error in central pressure estimation, although the transfer function involved has been previously validated [21,22]. The strong consistency in the relations of peripheral and central hemodynamic measurements with age, as observed in previous studies [30,31], also excludes any distortion by the transfer function. Our heritability estimate of PPc was consistent with the absence of intrafamilial aggregation of this trait.

Numerous previous studies, spanning a time interval from 1965 to date addressed the familial aggregation of systolic and diastolic pressure, but to our knowledge, few, if any, reported on the intrafamilial correlation of PPp. We are also unaware of any previous investigation showing intrafamilial aggregation of PWV, CAIx, the PAIx, or PPc. Our current study, in line with our heritability results, showed concordance of these traits with the exception of PPc in parent–offspring pairs, but not in spouse–spouse pairs. The high spouse–spouse correlation of mean arterial pressure is surprising. Significant concordance among spouses in systolic and diastolic pressure was, however, reported previously and has been attributed to assortative mating [32], the contribution of a common environment within the same generation of relatives or the home environment shared by members of the same household. To what extent these factors contributed to the currently observed parent–offspring correlations remains to be elucidated. Mean arterial pressure used for present analyses was calculated by means of widely accepted mathematical formula. This method, however, gives only approximate value. We therefore estimated heritability using mean arterial pressure derived from planimetry (h2 = 0.13). The lower heritability for this trait than for calculated mean arterial pressure taken from five consecutive readings might be explained by the fact that heritability tends to be higher for multiple measurements than for one measurement at a single point in time [14].

The present study must be interpreted within the context of its limitations and strengths. One potential limitation is that we used different devices to measure aortic PWV. Each of these devices allows, however, recordings with acceptable and well documented intraobserver and interobserver variability [23,24,26]. As the measurement technique of PWV was standardized within center and because we expressed the values in units of the within-center standard deviation, we believe that differences in the measurement technique can only have a minor influence, if any, on our estimates of heritability or intrafamilial aggregation. Second, our total sample size of 494 analyzable family members was smaller than in some other family-based studies [7,8,10,12,13,16–19]. We, however, implemented a quality control programme to minimize error in the conventional BP readings [33] from which we calculated PPp and mean arterial pressure. As previously reported [30], we found high intraobsever and interobserver reproducibility across our three centers for CAIx and PAIx. We adjusted for a large number of potentially important covariates. Finally, heritability estimates are population-specific, because they are influenced by family structure [34], population-specific genetic and environmental factors. In our analyses, we pooled subjects drawn from three European populations, but only after we had checked that the additive polygenic and total phenotypic variances did not differ significantly across populations.

Our study demonstrated moderate heritability of various indexes of arterial stiffness, including PPp, the CAIx and PAIx, and aortic PWV. We confirmed the contribution of genetic factors to these traits by significant intrafamilial concordance in parent–offspring pairs and by the absence of a significantly positive environmental component in the phenotypic associations among most of these arterial phenotypes. We showed for the first time weak, but significant, genetic correlations between several indexes of arterial stiffness, which strongly suggest that shared genes must contribute to these traits. Several genome-wide scans showed linkage of PPp with loci on chromosomes 7 [12,17,19] and 8 [17–19]. Some gene polymorphisms were also shown to be associated with age related increase in PPp [35]. The Framingham Study reported linkage of PWV with loci on chromosomes 1, 7, 13, and 15 [7]. Our study, therefore, highlights the necessity of further research into the genes that affect arterial stiffness. From a practical point of view, we would plea for a more standardized approach across studies in the adjustment of arterial phenotypes for host and lifestyle factors and potential confounders. Such a uniform approach might increase the comparability and external validity of future studies on the heritability and intra-familial concordance of arterial properties.

Acknowledgments

This study would not have been possible without the voluntary collaboration of the participants. The authors acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Sandra Covens, Katrien Staessen, and Renilde Wolfs (Studies Coordinating Centre, Leuven, Belgium).

Sponsorship: The European Project on Genes in Hypertension (EPOGH) is endorsed by the European Council for Cardiovascular Research and the European Society of Hypertension. Research included in this report was supported by the European Union (grants IC15-CT98-0329-EPOGH, QLGI-CT-2000-01137-EURNETGEN, and LSMH-CT-2006-037093 InGenious HyperCare); the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Vlaanderen, Ministry of the Flemish Community, Brussels, Belgium (G.0424.03 and G.0575.06); the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium (OT/99/28, OT/00/25 and OT/05/49); the Czech Ministry of Health (NG 7445-3); the Czech Society of Hypertension; and the Swiss National Foundation for Science (PROSPER 32000BO-111362/1). The study was also supported by the International Scientific Collaboration between Poland and Flanders (BIL 00/18 and BIL 05/22) and U.S. Public Health Service Resource grant (RR03655) from the National Center for Research Resources and Research grant (GM28356) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Jan A. Staessen is holder of the Pfizer Chair for Hypertension and Cardiovascular Research (http://www.kuleuven.be/mecenaat/leerstoelen/overzicht.htm).

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- BP

blood pressure

- CAIx

central augmentation index

- HR

heart rate

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- PAIx

peripheral augmentation index

- PPc

central pulse pressure

- PPp

peripheral pulse pressure

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Willum Hansen T, Staessen JA, Torp-Pedersen C, Rasmussen S, Thijs L, Ibsen H, Jeppesen J. Prognostic value of aortic pulse wave velocity as index of arterial stiffness in the general population. Circulation. 2006;113:664–670. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.579342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boutouyrie P, Tropeano AI, Asmar R, Gautier I, Benetos A, Lacolley P, Laurent S. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of primary coronary events in hypertensive patients: a longitudinal study. Hypertension. 2002;39 :10–15. doi: 10.1161/hy0102.099031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blacher J, Guerin AP, Pannier B, Marchais SJ, Safar ME, London GM. Impact of aortic stiffness on survival in end-stage renal disease. Circulation. 1999;99:2434–2439. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.18.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber T, Auer J, O’Rourke MF, Kvas E, Lassnig E, Berent R, Eber B. Arterial stiffness, wave reflections, and the risk of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2004;20;109:184–189. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105767.94169.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benetos A, Rudnichi A, Safar M, Guize L. Pulse pressure and cardiovascular mortality in normotensive and hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 1998;32:560–564. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dolan E, Thijs L, Li Y, Atkins N, McCormack P, McClory S, et al. Ambulatory arterial stiffness index as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in the Dublin Outcome Study. Hypertension. 2006;47:365–370. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000200699.74641.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell GF, DeStefano AL, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Chen MH, Vasan RS, et al. Heritability and a genome-wide linkage scan for arterial stiffness, wave reflection, and mean arterial pressure: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2005;112:194–199. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.530675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, van Rijn MJE, Schut AFC, Aulchenko YS, Croes EA, Zillikens MC, et al. Heritability of the function and structure of the arterial wall: findings of the Erasmus Rucphen Family (ERF) study. Stroke. 2005;36 :2351–2356. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185719.66735.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snieder H, Hayward CS, Perks U, Kelly RP, Kelly PJ, Spector TD. Heritability of central systolic pressure augmentation: a twin study. Hypertension. 2000;35:574–579. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.2.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.North KE, MacCluer JW, Devereux RB, Howard BV, Welty TK, Best LG, et al. Heritability of carotid artery structure and function: the Strong Heart Family Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1698–1703. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000032656.91352.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snieder H, Harshfield GA, Treiber FA. Heritability of blood pressure and hemodynamics in African- and European-American youth. Hypertension. 2003;41:1196–1201. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000072269.19820.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bielinski SJ, Lynch AI, Miller MB, Weder A, Cooper R, Oberman A, et al. Genome-wide linkage analysis for loci affecting pulse pressure: the Family Blood Pressure Program. Hypertension. 2005;46:1286–1293. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000191706.41980.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adeyemo AA, Omotade OO, Rotimi CN, Luke AH, Tayo BO, Cooper RS. Heritability of blood pressure in Nigerian families. J Hypertens. 2002;20 :859–863. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200205000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bochud M, Bovet P, Elston RC, Paccaud F, Falconnet C, Maillard M, et al. High heritability of ambulatory blood pressure in families of East African descent. Hypertension. 2005;45:445–450. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000156538.59873.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fava C, Burri P, Almgren P, Groop L, Hulthén UL, Melander O. Heritability of ambulatory and office blood pressure phenotypes in Swedish families. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1717–1721. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200409000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Rijn MJ, Schut AFC, Aulchenko YS, Deinum J, Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, Yazdanpanah M, et al. Heritability of blood pressure traits and the genetic contribution to blood pressure variance explained by four blood-pressure-related genes. J Hypertens. 2007;25:565–570. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32801449fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeStefano AL, Larson MG, Mitchell GF, Benjamin EJ, Vasan RS, Li J, et al. Genome-wide scan for pulse pressure in the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension. 2004;44:152–155. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000135248.62303.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atwood LD, Samollow PB, Hixson JE, Stern MP, MacCluer JW. Genome-wide linkage analysis of pulse pressure in Mexican Americans. Hypertension. 2001;37:425–428. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Camp NJ, Hopkins PN, Hasstedt SJ, Coon H, Malhotra A, Cawthon RM, Hunt SC. Genome-wide multipoint parametric linkage analysis of pulse pressure in large, extended Utah pedigrees. Hypertension. 2003;42:322–328. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000084874.85653.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.41st World Medical Assembly: Declaration of Helsinki. Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. Bull Pan Am Health Organ. 1990;24:606–609. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen CH, Nevo E, Fetics B, Pak PH, Yin FC, Maughan WL, Kass DA. Estimation of central aortic pressure waveform by mathematical transformation of radial tonometry pressure. Validation of generalized transfer function. Circulation. 1997;95:1827–1836. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.7.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pauca AL, O’Rourke MF, Kon ND. Prospective evaluation of a method for estimating ascending aortic pressure from the radial artery pressure waveform. Hypertension. 2001;38:932–937. doi: 10.1161/hy1001.096106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asmar R, Benetos A, Topouchian J, Laurent P, Pannier B, Brisac AM, et al. Assessment of arterial distensibility by automatic pulse wave velocity measurement. Validation and clinical application studies. Hypertension. 1995;26:485–490. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kool MJF, van Merode T, Reneman RS, Hoeks APG, Struyker Boudier HAJ, Van Bortel LMAB. Evaluation of reproducibility of a vessel wall movement detector system for assessment of large artery properties. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:610–614. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.5.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zebekakis PE, Nawrot T, Thijs L, Balkestein EJ, van der Heijden-Spek J, Van Bortel LM, et al. Obesity is associated with increased arterial stiffness from adolescence until old age. J Hypertens. 2005;23:1839–1846. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000179511.93889.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilkinson IB, Fuchs SA, Jansen IM, Spratt JC, Murray GD, Cockcroft JR, Webb DJ. Reproducibility of pulse wave velocity and augmentation index measured by pulse wave analysis. J Hypertens. 1998;16:2079–2084. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816121-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Statistical Analysis for Genetic Epidemiology [computer program]. S.A.G.E. 5.1. http://darwin.cwru.edu/sage/2006.

- 28.Freeman MS, Mansfield MW, Barrett JH, Grant PJ. Insulin resistance: an atherothrombotic syndrome. The Leeds family study. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89:161–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laurent S. Surrogate measures of arterial stiffness: do they have additive predictive value or are they only surrogates of a surrogate? Hypertension. 2006;47:325–326. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000200701.43172.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wojciechowska W, Staessen JA, Nawrot T, Cwynar M, Seidlerová J, Stolarz K, et al. Reference values in white Europeans for the arterial pulse wave recorded by means of the SphygmoCor device. Hypertens Res. 2006;29 :475–483. doi: 10.1291/hypres.29.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Rourke MF, Nichols WW. Aortic diameter, aortic stiffness, and wave reflection increase with age and isolated systolic hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:652–658. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153793.84859.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knuiman MW, Divitini ML, Welborn TA, Bartholomew HC. Familial correlations, cohabitation effects, and heritability for cardiovascular risk factors. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6:188–194. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(96)00004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuznetsova T, Staessen JA, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, Babeanu S, Casiglia E, Filipovsky J, et al. Quality control of the blood pressure phenotype in the European Project on Genes in Hypertension. Blood Press Monit. 2002;7 :215–224. doi: 10.1097/00126097-200208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsu FC, Zaccaro DJ, Lange LA, Arnett DK, Langefeld CD, Wagenknecht LE, et al. The Impact of Pedigree Structure on Heritability Estimates for Pulse Pressure in Three Studies. Hum Hered. 2005;60:63–72. doi: 10.1159/000087971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mourad JJ, Ducailar G, Rudnicki A, Lajemi M, Mimran A, Safar MR. Age-related increase of pulse pressure and gene polymorphisms in essential hypertension: a preliminary study. JRAAS. 2002;3:109–115. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2002.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]