Abstract

Newborn rhesus macaques were infected with two chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) strains which contain unique human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) env genes and exhibit distinct phenotypes. Infection with either the CCR5-specific SHIVSF162P3 or the CXCR4-utilizing SHIVSF33A resulted in clinical manifestations consistent with simian AIDS. Most prominent in this study was the detection of severe thymic involution in all SHIVSF33A-infected infants, which is very similar to HIV-1-induced thymic dysfunction in children who exhibit a rapid pattern of disease progression. In contrast, SHIVSF162P3 induced only a minor disruption in thymic morphology. Consistent with the distribution of the coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5 within the thymus, the expression of SHIVSF162P3 was restricted to the thymic medulla, whereas SHIVSF33A was preferentially detected in the cortex. This dichotomy of tissue tropism is similar to the differential tropism of HIV-1 isolates observed in the reconstituted human thymus in SCID-hu mice. Accordingly, our results show that the SHIV-monkey model can be used for the molecular dissection of cell and tissue tropisms controlled by the HIV-1 env gene and for the analysis of mechanisms of viral immunopathogenesis in AIDS. Furthermore, these findings could help explain the rapid progression of disease observed in some HIV-1-infected children.

Neonatal human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection is often associated with a more rapid disease progression and a higher mortality rate than infection acquired later in life (reviewed in reference 35). In general, pediatric HIV-1-associated disease is separable into two distinct modes of clinical progression: one that is extraordinarily fast and another that approximates the slower tempo observed in the majority of adults. In this bimodal distribution of disease, 20 to 30% of children have an early onset of symptoms at less than 12 months of age and death within 2 to 3 years. The remaining infected children display a later onset of symptoms but nevertheless die within 5 to 10 years. Interestingly, most of these long-surviving children maintain a persistently high viremia and normal CD4+ lymphocyte levels for many months following infection (1, 10, 35); this clinical picture sharply contrasts with the rapid clearance of HIV-1 viremia that is typical of adult infection. The sustained high-level viremia in infected children may result from persistent viral replication within the progressively expanding lymphoid cell mass (24), including the thymus, which represents the principal source of T lymphopoiesis during early life (15).

HIV-1 infection of the thymus has been demonstrated in autopsy specimens from infected fetuses and children (19, 33). This finding is consistent with the expression pattern of CD4 as well as the chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR5 on thymocytes (4, 21, 31, 38). Taken together with the hyperproliferative state of the neonatal thymus, these findings indicate that this organ may represent a major site for HIV-1 infection and pathogenesis. Indeed, a population of infected children exhibit an immunophenotypic profile similar to that observed in children with the severe congenital thymic defect known as DiGeorge anomaly (22). The pathogenesis of AIDS in this age group may involve virus-induced disruption of the thymic generative microenvironment, leading to a reduction of the postthymic reservoir of peripheral lymphocytes (22). In HIV-1-infected children, markers of thymic dysfunction are predictive of survival outcome (32) and signal the rapid progression to death, independent of viral loads. Thus, the bimodal pattern of disease progression in pediatric AIDS may reflect both the vulnerability of the neonatal thymus and differences in the potential of viral variants for thymic destruction.

Numerous factors, including time and mode of infection and viral heterogeneity and phenotype (cytopathicity and coreceptor utilization), have been correlated with the resultant biological behavior of HIV-1 in the developing thymus. However, practical limitations have hindered detailed studies of the mechanism by which HIV-1 disrupts thymopoiesis in newborn children. Importantly, several in vivo and in vitro systems, including the SCID-hu Thy/Liv mouse, human thymic organ culture, and thymocyte-epithelial cell culture, have provided insight into mechanisms associated with HIV-1-mediated thymic destruction and the establishment of viral latency (4, 6, 7, 20, 23, 31, 38). However, these models have significant limitations because they do not allow for full development of lymphoid organs or the generation of a virus-specific host immune response.

Experimental infection of newborn Asian macaques with selected strains of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), or chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) causes a fatal AIDS-like disease that closely recapitulates the spectrum of disease in HIV-1-infected children (2, 5, 28, 30). We selected two phenotypically distinct SHIV strains for in vivo studies in infant rhesus macaques: SHIVSF33A utilizes the CXCR4 coreceptor and produces a rapid decline of CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood in both infant and adult macaques, and SHIVSF162P3 utilizes the CCR5 coreceptor and causes depletion of CD4+ T cells in the gastrointestinal tract in adult macaques (14, 28, 29). We report that both of these SHIV strains induce simian AIDS in infant macaques but that each strain is associated with distinct patterns of viral expression and pathology in the thymus. These findings allow for the study of thymic disruption, as well as the analysis of pathogenic mechanisms in other lymphoid organs, in a highly manipulatable animal model for lentivirus infection and AIDS pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Rhesus macaques (Maccaca mulatta) were colony bred at the California National Primate Research Center and were born to dams which were negative for antibodies to SIV, type D retroviruses, and simian T-cell leukemia virus type 1. Newborns were removed from their mothers and reared in a primate nursery in accordance with the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care standards. Phlebotomies and virus inoculations were performed with animals anesthetized with ketamine-HCl. Peripheral blood (0.5 to 1.0 ml in EDTA) was collected immediately before virus inoculation and regularly thereafter for monitoring viral and immunological parameters. Complete physical examinations were performed daily by the California National Primate Research Center veterinary staff to monitor for weight gain, opportunistic infections, and other clinical signs of disease. Animals were euthanatized according to a predetermined timetable or upon meeting three of the following criteria: (i) weight loss of >10% in 2 weeks; (ii) chronic diarrhea unresponsive to treatment; (iii) infections unresponsive to antibiotics; (iv) inability to maintain body heat or fluids without supplementation; (v) persistent, marked hematological abnormalities, including lymphopenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, or neutropenia; and (vi) persistent, marked splenomegaly or hepatomegaly.

Viruses and inoculations.

Neonatal macaques were inoculated with 0.5 ml of cell-free virus by the intravenous route between 24 and 48 h postpartum. All viral stocks were quantitated for viral RNA by real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) (see below) and for SIV p27gag by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Beckman Coulter, Hialeah, Fla.). SHIVSF33A was prepared by passage in CEMX174 cells as previously described (28). All SHIVSF33A-infected newborns received cell-free virus corresponding to 2.8 × 106 copies of viral RNA and 3.7 ng of SIV p27gag. The variant of SHIVSF162P3 used in this study, designated passage 3, was propagated in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (14) as well as in rhesus PBMC (Advanced BioScience Laboratories, Kensington, Md.). Neonates Mmu33486, Mmu33493, and Mmu33530 received cell-free SHIVSF162P3 propagated in human PBMC corresponding to 19.4 × 106 copies of viral RNA and 33 ng of SIV p27gag. Neonates Mmu33548, Mmu33554, and Mmu3355 received cell-free SHIVSF162P3 propagated in rhesus PBMC corresponding to 25.7 × 106 copies of viral RNA and 55 ng of SIV p27gag.

Evaluation of T-cell subsets in peripheral blood and plasma viral loads.

Immunophenotypic characterization of peripheral blood lymphocytes was performed with a FACscan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, Calif.) together with monoclonal antibodies specific for CD3 (SP34), CD4 (M-T477), and CD8 (SK1), all obtained from BD Biosciences. Staining was performed with 50 μl of whole blood or purified cells (106 to 107/ml) in phosphate-buffered saline-0.5% bovine serum albumin. Red blood cells were lysed and/or lymphocytes were fixed in 1% formaldehyde with a Coulter T Q-Prep system (Beckman Coulter). Controls consisted of unstained, isotype-stained, and single-color-stained samples to verify the background and specificity of each antibody. Complete blood counts were performed with an ABX Diagnostics Baker 9010 electronic cell counter together with manual enumeration of leukocytes.

Quantitation of virion-associated RNA in plasma was performed by RT-PCR with an ABI Prism 7700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and primers specific for SIVmac239 gag, as previously described (26).

Necropsy and tissue collection.

A complete necropsy, which included gross and microscopic examination of all tissues, was performed on each euthanatized animal. Tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at 6 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histologic evaluation. The histologic description of simian AIDS was based on severe generalized lymphoid depletion in lymph nodes, spleen, and thymus and detection of opportunistic infections. Histologic grading of the thymus was performed according to the criteria listed in Table 1. To determine the distribution of SHIV RNA, sections were cut at 6 μm and subjected to in situ hybridization.

TABLE 1.

Histologic grading of the thymus in SHIV-infected neonatal macaques

| Gradea | Appearance of:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Cortex | Medulla | |

| 4 | Virtually no lymphoid cortex visible; thinning of the cortical area; presence of only histiocytes and stroma; no discernible corticomedullary junction | Only individual or patchy aggregates of lymphocytes on a background of reticular stroma and histiocytes |

| 3 | Decreased cortical thickness and density with increased prominence of cortical stroma and numerous histiocytes; in some lobules only a very “moth-eaten” appearance with irregular aggregates of lymphocytes on a stromal-histiocytic background; very poorly detectable corticomedullary junction | Irregular patchy aggregates of lymphocytes within a reticular stroma with prominent blood vessels and many histiocytes |

| 2 | Thinning of cortex in some lobules and mildly decreased density of lymphocytes; mildly increased prominence of cortical stroma and histiocytes | Slightly diluted lymphoid population with more than occasional histiocytes; stromal cells, and blood vessels |

| 1 | Normal appearance of cortex with respect to thickness and density of lymphocytes; only scattered histiocytes; very little stroma visible | Normal appearance of medulla characterized by a dense population of lymphocytes with only occasional histiocytes, stromal cells, blood vessels, and scattered thymic corpuscles |

The degree of thymic dysinvolution was subjectively quantified against independent criteria for the cortex and medulla. The assigned grade reflects the assessment of all thymic lobules within each section.

In situ hybridization.

In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (16) with slight modification. In this modified protocol, a commercially available hybridization solution (S33004; Dako, Carpinteria, Calif.) was used together with a cocktail of 11 individual digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes. These probes are complementary to transcripts encoding all SIVmac239 proteins, with the exception of env and nef and exhibited matched hybridization characteristics. Both sense and antisense riboprobes were generated by in vitro transcription by using the Ampiscribe T7 and T3 systems (Epicenter Technologies, Madison, Wis.), substituting 2.6 mM digoxigenin-11-UTP (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Ind.) and 4.9 mM unlabeled UTP for the recommended 7.5 mM UTP in the final reaction mixture. To monitor signal specificity, duplicate tissue sections were prepared and simultaneously hybridized with 2.5 × 10−5 M sense or antisense riboprobe cocktail. Hybridized probe was detected with an antidigoxigenin alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody (Roche Diagnostics) and nitroblue tetrazolium-5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) substrate. Sections were counterstained with nuclear fast red. Combined in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously (9). This protocol utilized tyramide signal amplification (fluorescein isothiocyanate-Tyr; Perkin-Elmer, Boston, Mass.) for the detection of hybridized probes, together with polyclonal anti-CD3 (Dako) and anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-Alexa 633 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) antibodies for immunophenotypic characterization.

Statistical analysis.

Growth rates (weight gained [in grams] per day) were calculated for SHIV-infected neonates and 30 age-matched, uninfected control macaques reared under the same conditions over the first 72 days of life. Estimation of unknown parameters and tests of hypotheses were performed with the MIXED procedure of SAS (2001; version 8.02). For these analyses, weight was treated as a dependent variable and day of life was considered a continuous, independent variable, allowing for the estimation of daily weight gain through simple linear regression.

RESULTS

Induction of AIDS in infant macaques. (i) Rapid induction of AIDS in infant macaques inoculated with SHIVSF33A and SHIVSF162P3.

To evaluate the pathogenesis associated with CXCR4 and CCR5 viruses in the nonhuman primate model of pediatric AIDS, six newborn rhesus macaques were inoculated with either SHIVSF33A or SHIVSF162P3 and monitored over the entire course of disease. All six infants showed a generalized failure to thrive, which was confirmed by comparison against pediatric standards of weight gain and physical development of rhesus macaques (30). Assessment of 30 uninfected, age-matched controls (0 to 72 days of age) reared under similar conditions showed an average daily weight gain of 6.54 g/day (standard error = 0.04). In contrast, the weight gain of infants infected with either SHIVSF33A or SHIVSF162P3 was 3.92 g/day (standard error = 0.12) over the same age interval. Importantly, growth rates for SHIVSF33A-infected infants were indistinguishable from those of SHIVSF162P3-infected infants. However, SHIVSF33A-infected infants typically exhibited more severe outward signs of clinical disease, including lethargy, loss of appetite, diarrhea, dehydration, and icterus.

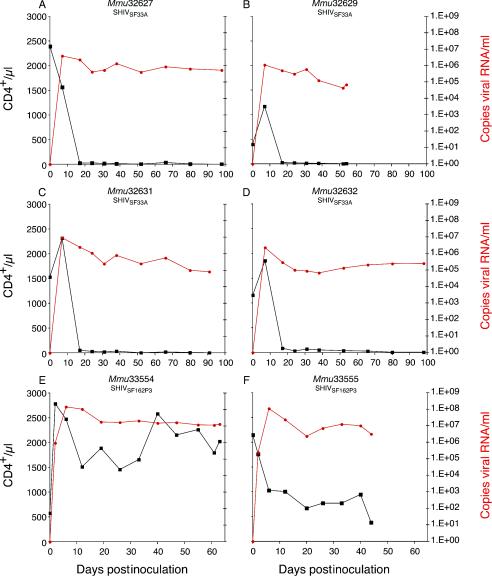

In four of four SHIVSF33A-infected infants, a profound, synchronous depletion of peripheral blood CD4+ T lymphocytes to <50/μl was observed by 1 to 3 weeks postinoculation (p.i.) (Fig. 1A to D). At euthanasia, CD8+ T cells were <360/μl. In marked contrast, infection with SHIVSF162P3 was associated with only a moderate decline in the absolute number of peripheral blood CD4+ T lymphocytes at 2 to 3 weeks p.i. (Fig. 1E and F). Interestingly, the rebound of CD4+ T-lymphocyte numbers in one infant (Mmu33554), at 5 to 7 weeks p.i., is consistent with the kinetics of CD4+ T-lymphocyte changes in SHIVSF162P3-infected juvenile or adult rhesus monkeys (14). However, a similar rebound was not observed in another SHIVSF162P3-infected infant (Mmu33555) euthanatized at <7 weeks p.i. Furthermore, the absolute frequency of peripheral CD8+ T lymphocytes detected in this infant was suppressed (198 to 683/μl) throughout the entire course of disease, whereas Mmu33554 showed a progressive expansion of this lymphocyte subset to 1,984/μl at the time of euthanasia. In infants infected with either SHIVSF33A or SHIVSF162P3, peak plasma viremia (105 to 107 copies of RNA/ml) was detected by 2 weeks p.i., concomitant with the initiation of peripheral CD4+ T-lymphocyte decline (Fig. 1). Furthermore, both groups of animals maintained high levels of plasma viremia throughout the entire disease course. Antiviral plasma immunoglobulin G, based on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with whole SIVmac251 (27), was not detected in either SHIVSF33A- or SHIVSF162P3-inoculated infants over the entire course of disease (data not shown). These serological results contrast the SIV-specific antibody response observed within 10 weeks following perinatal infection with the less pathogenic SIV molecular clones mac239 and mac1A11 (30), further illustrating the inability of these SHIV-infected infants to combat opportunistic infections (see below). In summary, within 7 to 14 weeks p.i., all SHIVSF33A- and SHIVSF162P3-infected infants exhibited deteriorating health consistent with simian AIDS.

FIG. 1.

Viral load and CD4+ T-cell numbers in infant macaques infected with SHIVSF33A and SHIVSF162P3. Viral RNA levels per milliliter of plasma (red) and absolute CD4+ T-cell numbers per microliter of whole blood (black) are shown for infants infected with SHIVSF33A (A to D) or SHIVSF162P3 (E and F). The final data sets on each graph correspond to the number of days postinoculation at which complications from simian AIDS mandated euthanasia.

(ii) Histopathologic findings in SHIV-infected infants exhibiting AIDS.

At necropsy, all SHIV-infected infants (Mmu32627, Mmu32629, Mmu32631, Mmu32632, Mmu33554, and Mmu33555) showed histopathologic lesions associated with simian AIDS, including generalized severe lymphoid depletion of peripheral and alimentary lymph nodes and spleen, and opportunistic infections (e.g., cytomegalovirus, adenovirus, Candida albicans, and Cryptosporidium) (Table 2). Comparative histopathology revealed few significant differences in the presence and severity of lesions associated with SHIVSF33A and SHIVSF162P3 infection; however, a marked distinction in thymic pathology was observed between the two groups of SHIV-infected infants.

TABLE 2.

Pathologic changes in SHIV-infected infants exhibiting AIDS

| Animal | Virus inoculation | Euthanasia (days p.i.) | Pathologic changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mmu32627 | SHIVSF33A | 98 | Thymic atrophy; mixed lymphoid hyperplasia-depletion; enteric villus blunting, hemosiderosis, and cryptosporidiosis; oral candidiasis |

| Mmu32629 | SHIVSF33A | 56 | Thymic atrophy; mixed lymphoid hyperplasia-depletion; choledochocystitis with intranuclear inclusions (cytomegalovirus); portal hepatitis with viral inclusions (cytomegalovirus); pancreatitis with viral inclusions (adenovirus); chronic interstitial pneumonia with viral inclusions (cytomegalovirus) |

| Mmu32631 | SHIVSF33A | 91 | Thymic atrophy; generalized lymphodepletion; chronic interstitial pneumonia with viral inclusions (adenovirus); chronic pyelonephritis; enteric colibacillosis; oral candidiasis |

| Mmu32632 | SHIVSF33A | 98 | Thymic atrophy; mixed pattern of lymphoid hyperplasia-depletion; enteric cryptosporidiosis; colonic colibacillosis; oral candidiasis; encephalitis with glial nodules |

| Mmu33554 | SHIVSF162P3 | 63 | Mixed lymphoid hyperplasia-depletion; proliferative cholangitis (cryptosporidiosis) with viral inclusions (adenovirus); choledochocystitis (cryptosporidiosis); pyelonephritis with viral inclusions (cytomegalovirus); chronic obliterative pancreatitis (probable adenovirus) with proliferative ductitis (cryptosporidiosis); typhlocolitis; oral candidiasis |

| Mmu33555 | SHIVSF162P3 | 44 | Generalized lymphodepletion (severe in ileum and duodenum); cholangitis with viral inclusions (adenovirus); pneumonia with viral inclusions (cytomegalovirus); enteric cryptosporidiosis; typhlocolitis; oral candidiasis |

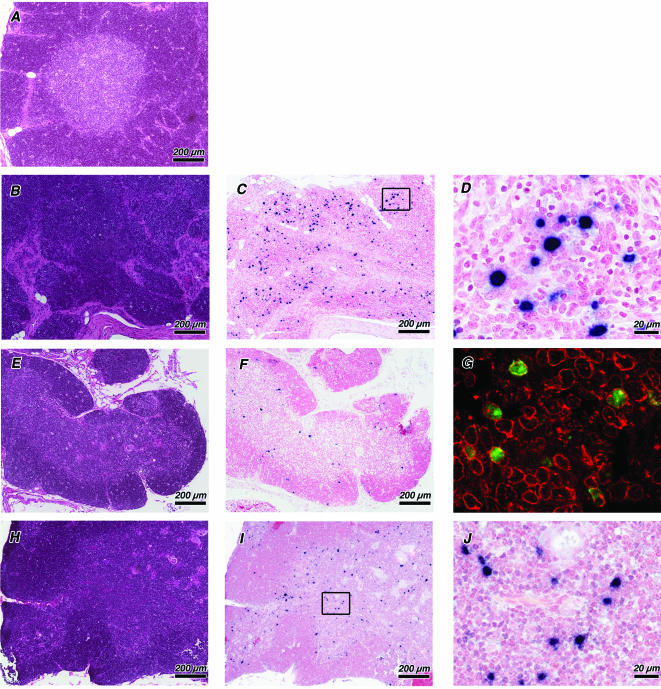

In all SHIVSF33A-infected infants, very little thymic tissue was discernible at the gross level. Microscopic examination showed a pattern of lesions consistent with thymic dysinvolution (19), characterized by cortical ablation and severe lymphoid depletion of the medulla, with only patchy aggregates of lymphocytes remaining on a stromal-histiocytic background. Although the location and configuration of blood vessels appeared normal, Hassell's corpuscles were rarely observed (Fig. 2B). In contrast, lesions of the thymus were less severe in both SHIVSF162P3-infected infants. Compared to the thymus from an uninfected control infant (Fig. 2A), lesions associated with SHIVSF162P3 infection were characterized by only a moderate decrease in cortical thickness and density and a slight reduction of medullary lymphoid cells (Fig. 2E and H). A potential explanation of the difference in thymic pathology associated with these SHIVs is provided by the detection of productively infected cells by using RNA in situ hybridization. A striking difference in the pattern of viral RNA expression was observed within the thymi of SHIVSF33A-infected neonates compared to SHIVSF162P3-infected neonates. Expression of SHIVSF33A RNA was most evident within large blastoid cells distributed evenly throughout the thymic lobule (Fig. 2C and D). By using combined in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry, these highly infected thymocytes were determined to be of the T-cell lineage (Fig. 2G). In SHIVSF162P3-infected infants, the detection of viral RNA was restricted to smaller cells, consistent with lymphocytes, in the thymic medulla (Fig. 2F, I, and J).

FIG. 2.

Morphological alterations and viral localization in the thymi of SHIV-infected infant macaques with simian AIDS. Sections of thymi from an uninfected macaque at 3 months of age (A) (Mmu33999) as well as from infants infected with SHIVSF33A (B to D and G) (Mmu32637) and SHIVSF162P3 (E and F) (Mmu33555) and (H to J) (Mmu33554) are shown. Adjacent sections from the same tissue blocks were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (A, B, E, and H) to evaluate tissue architecture and processed by using in situ hybridization to detect viral RNA (C, D, F, G, I, and J). Productively infected cells are identified by an insoluble black precipitate representing the in situ hybridization signal. Higher-resolution micrographs (D and J), corresponding to the areas outlined with black boxes, are shown for sections C and I. SHIVSF33A infection resulted in severe cortical and medullary depletion (B), with productively infected cells evenly distributed within residual thymic tissue (C). Combined in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry (G) show SHIVSF33A RNA (green fluorescence) restricted to CD3+ thymocytes (red fluorescence). SHIVSF162P3 infection is characterized by only a moderate decrease in cortical thickness and mild reduction of medullary lymphoid cells (E and H). SHIVSF162P3 expression is restricted to the thymic medulla (F and I) within cells consistent in size with lymphocytes (J). Magnifications are indicated by bars for each bright-field photomicrograph. Magnification of fluorescence micrograph, ×40.

Acute infection of neonates. (i) Kinetics of viral replication and T-cell depletion in SHIV-infected neonates.

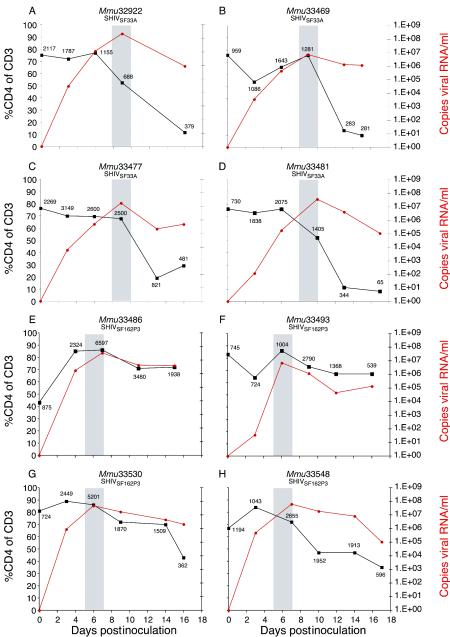

To evaluate the differential pathogenesis of these viruses on the neonatal thymus during acute infection, we inoculated four additional newborns with SHIVSF33A and four newborns with SHIVSF162P3. Between 15 and 17 days p.i., all eight neonates were euthanatized. In SHIVSF33A-infected neonates, peak viremia was attained between 8 and 10 days p.i. (Fig. 3A to D, shaded areas), concurrent with a dramatic decline in the percentage as well as the absolute number of peripheral blood CD4+ T lymphocytes. However, semiweekly assessment revealed that this decline was initiated prior to the attainment of peak viremia. Interestingly, the more rapid replication of SHIVSF162P3, with peak plasma viremia between 5 and 7 days p.i. (Fig. 3E to H, shaded areas), is reminiscent of the replication kinetics of SIVmac239 in infant rhesus macaques (36).

FIG. 3.

Viral load and CD4+ T-cell numbers in neonatal macaques during acute infection with SHIVSF33A and SHIVSF162P3. Viral RNA levels per milliliter of plasma (red) and the relative frequency (percentage) of CD4+ T cells (black) are shown for neonates infected with SHIVSF33A (A to D) or SHIVSF162P3 (E to H). The absolute frequency of CD4+ T cells per microliter of whole blood is shown adjacent to each data point. Shaded regions on each graph represent the interval during which peak plasma viremia was attained.

(ii) Thymic pathology in neonatal macaques following acute infection with SHIVSF162P3 and SHIVSF33A.

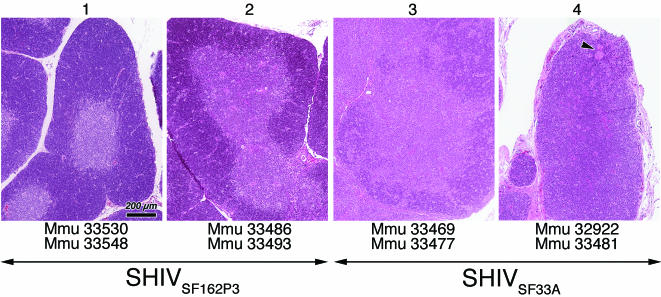

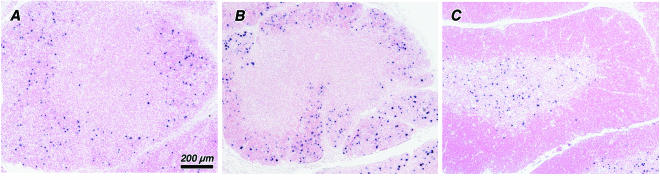

The grading system to evaluate thymic histopathology is shown Table 1. Overall, the histopathologic alterations of the thymus from SHIVSF162P3-infected neonates were mild (grades 1 and 2), with various degrees of cortical thinning and slight depletion of both cortical and medullary thymocytes. In comparison, the pathologic changes of the thymus associated with SHIVSF33A were more severe (grades 3 and 4), ranging from moderate lymphoid depletion to precocious involution (19), manifested by a marked paucity to virtual absence of cortical thymocytes and blurring to loss of corticomedullary demarcation. In the most severe case, that of a SHIVSF33A-infected neonate which died from simian AIDS at 16 days p.i. (Fig. 4, panel 4), a single Hassell's corpuscle abuts the thymic capsule (arrow), illustrating the gravity of cortical disruption associated with this virus.

FIG. 4.

Grading scale of thymic morphology in neonatal rhesus macaques. Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections of thymus illustrating the spectrum of lesions observed in SHIVSF33A- and SHIVSF162P3-infected macaques at 15 to 17 days p.i. are shown. The grade assigned to each section is shown at the top and is based on morphological criteria described in Table 1. Arrows beneath the photomicrographs illustrate the spectrum of lesions which were observed for both SHIVSF33A- and SHIVSF162P3-infected neonates. Animal identification numbers beneath photomicrographs illustrate the lesion grade assigned to each neonate. The arrowhead in the far right photomicrograph marks the location of a Hassell's corpuscle adjacent to the thymic capsule, illustrating the severity of cortical disruption induced by SHIVSF33A. All photomicrographs are reproduced at the same magnification, as indicated by the bar.

(iii) Patterns of viral expression in the thymus following acute infection with SHIVSF162P3 and SHIVSF33A.

In SHIVSF162P3-infected neonates, viral expression was highly restricted to lymphocytes resident in the thymic medulla (Fig. 5C), with only a few (<5%) productively infected cells scattered throughout the cortex. This pattern is similar to previous descriptions of SIVmac239 and SIVmac251 infection in infant and adult rhesus macaques (25, 36) and to SHIVSF162P3-infected infants in the latter stages of disease (see above). In contrast, SHIVSF33A was detected predominantly within thymocytes of the inner cortex (Fig. 5A). A few productively infected cells were dispersed throughout the cortex and within the medulla; however, this variation in the pattern of SHIVSF33A RNA detection was not correlated to the degree of thymic involution.

FIG. 5.

Localization of viral RNA in the thymus following acute infection with SHIVSF33A and SHIVSF162P3. Sections of thymi from infant macaques infected with SHIVSF33A at 16 days (A) (Mmu33477) and at 32 days (B) (Mmu33486) p.i. and from a SHIVSF162P3-infected macaque at 15 days p.i. (C) (Mmu33477), showing the distribution of viral RNA, are shown. Productively infected cells are identified by an insoluble black precipitate representing the in situ hybridization signal. In SHIVSF33A-infected infants viral expression is highest within the inner cortex (A) but appears to disseminate concomitant with cortical depletion (B). In SHIVSF162P3-infected infants, viral expression is highly restricted to the thymic medulla (C). All photomicrographs are reproduced at the same magnification, as indicated by the bar.

To study the pathway of SHIVSF33A dissemination within the thymus, we evaluated the histopathology and pattern of viral distribution within the thymi from an additional group of three infant macaques. These infants were inoculated with SHIVSF33A as described above (see Materials and Methods) and were euthanatized between 32 to 38 days p.i. The patterns of CD4+ T-cell depletion and viral replication in these infants were indistinguishable from those described above for SHIVSF33A infection (data not shown). Thymic tissue was detected grossly in all three infants and was characterized microscopically by moderate to severe cortical and medullary lymphoid depletion. Evaluation of viral RNA distribution showed that the majority of productively infected cells were resident in the thymic cortex (Fig. 5B). However, unlike the pattern of infection observed between 15 and 17 days p.i., the number of infected cells was both increased and evenly distributed throughout the thymic cortex.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that simian AIDS was rapidly induced in infant rhesus macaques following perinatal infection with either SHIVSF162P3 or SHIVSF33A. However, each of these pathogenic SHIVs exhibited divergent effects on the peripheral CD4+ T-lymphocyte pool and on the thymus, coincident with the development of simian AIDS. The hematological profile of SHIVSF33A-infected infants, showing profound depletion of CD4+ lymphocytes in the periphery, was similar to that of HIV-1-infected children with rapidly progressing disease; such children are defined as thymic dysfunctional (20, 22, 32). In contrast, the levels of CD4+ lymphocytes in the periphery were not profoundly depleted in SHIVSF162P3-infected infants. Because the thymus is the primary source of T lymphopoiesis during early life, differences in the thymic pathology observed in SHIVSF162P3- and SHIVSF33A-infected infants suggest that infection of this organ is central to mechanisms by which these viruses induce disease. In all SHIVSF33A-infected infants that were allowed to progress to fatal AIDS, the severity of lesions was consistent with acquired thymic dysplasia in children with congenital HIV-1 disease (19). In contrast, the histopathologic alterations of the thymus in SHIVSF162P3-infected infants were mild and similar to acute involution in HIV-1-infected children (19) and to those previously described in infant macaques infected with SIVmac239, a virus also utilizing the CCR5 coreceptor (36). These differences in pathogenesis as well as tissue tropism of SHIVSF33A and SHIVSF162P3 within the thymus are consistent with the expression patterns of CXCR4 and CCR5 on developing thymocytes. Studies of thymocyte development within the human fetus as well as adult rhesus macaques have demonstrated that CXCR4 is highly expressed on immature T-cell progenitors resident to the thymic cortex. This CXC chemokine is down regulated during thymocyte differentiation and transit across the corticomedullary junction, whereas CCR5 is expressed predominately on mature, medullary thymocytes (4, 21, 38, 39).

Our results provide the basis for a model in which the immunodeficiency induced by perinatal infection of macaques with SHIVSF162P3 and SHIVSF33A may result from disruption of thymopoiesis. However, the mechanisms by which these two viruses impair T-cell development appear to be different. These mechanisms, which could include direct cell killing, blockade of development, or the defective generation and maturation of T cells, appear to be dependent on the populations of thymocytes infected by each virus. Accordingly, differences in T-cell depletion associated with SHIVSF33A and SHIVSF162P3 may reflect the more ubiquitous expression of CXCR4 in the thymus compared to CCR5. A similar situation has been described for human lymphoid organ culture, in which there was no intrinsic difference between the cytopathicities of CCR5- and CXCR4-utilizing HIV-1 variants towards their cognate CD4+ T-lymphocyte targets (13). However, the severe loss of T lymphocytes associated with SHIVSF33A infection may not be explained strictly on the basis of direct killing of productively infected cells. Rather, we suggest that the depletion of immature CXCR4+ thymocytes imposes a bottleneck or blockade of thymopoiesis, which ultimately leads to the exhaustion of mature T cells. In contrast, the underlying cause of immunodeficiency in SHIVSF162P3-infected infants appears to result from the defective generation and maturation of T cells, a scenario which could be explained by virus-induced change in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I expression. In support of this notion, Rosenzweig et al. showed that infection of neonatal macaques with SIVmac239 was correlated to the global modulation of MHC class I within the thymus (36). Indeed, the generation of dysfunctional CD8+ cells in HIV-1-infected children is believed to result from the dysregulation of MHC class I in the thymus (20).

Our findings with monotropic SHIVs raise intriguing questions with regard to the mechanisms by which other chimeric SHIVs are believed to induce immunodeficiency. For example, SHIVDH12R, a dualtropic (CCR5/CXCR4), acutely pathogenic virus, causes profound depletion of peripheral CD4+ cells and primarily targets the thymic medulla (18). In contrast, SHIVSF33A clearly showed localization to the thymic cortex throughout the course of infection. Studies on the dualtropic SHIV89.6 and its pathogenic derivatives indicate that the fusogenic potential of the env gene is directly related to virus load and pathogenicity of virus in adult macaques (11, 12). Interestingly, both SHIVSF162P3 and SHIVSF33A established similar levels of plasma viremia and rapid progression to AIDS, although the former virus contained an env gene that was less fusogenic than the latter (8, 17). Taken together, these findings suggest that the biological behavior of dualtropic viruses may be different from that of either CCR5 or CXCR4 monotropic strains.

In HIV-1-infected infants, it has been difficult to study the influence of viral phenotype on AIDS. Although disease progression has been ascribed to the evolution of virus, leading to an escape of CCR5-utilizing strains from antiviral C-C chemokine control (37), the relative in vivo pathogenicities of CCR5- and CXCR4-tropic viruses has not been well defined. Diverse strains of HIV-1 which utilize CXCR4 and/or CCR5 have been isolated from newborn children who rapidly progressed to AIDS (34). Nevertheless, the viral isolates detected during the asymptomatic stages of disease generally use only CCR5 as a coreceptor (37). Importantly, in HIV-1-infected children the characterization of the viral phenotype has been based largely upon the determination of coreceptor utilization of variants isolated from peripheral or cord blood cells. This approach may not accurately predict the phenotype of the original founding virus, further illustrating the need for animal models to evaluate the role of properties, governed by the env gene, in the induction of fatal immunodeficiency.

The SCID mouse engrafted with human thymic tissue has been used to investigate the influence of viral phenotype on the mechanisms by which HIV-1 affects T-cell development and function. By using this xenograft model, a dichotomy in the pattern by which CCR5- and CXCR4-tropic viruses infect the thymus has been demonstrated (3, 21, 38). This pattern is presumably dictated by the expression of cognate viral receptors on discrete thymocyte subsets, whereby CCR5-utilizing viruses are restricted to the medulla and CXCR4-tropic stains infect cells within both the cortex and medulla (3). These differences in viral tropism in the thymus have been correlated to the degree of organ destruction and the potential establishment of viral latency within naïve T cells (3, 6). Although the SCID-hu mouse allows for human thymopoiesis (31), this model may not accurately recapitulate the complete pathogenic spectrum in HIV-1-infected children. This is exemplified by the observation that virus loads in the SCID-hu reconstituted thymus are higher than those measured in vivo in the infected human thymus, probably because an antiviral host immune response is absent in the SCID-hu model (6).

Our analysis of the thymic pathology and viral expression in SHIVSF162P3 and SHIVSF33A infection in infant rhesus macaques supports and extends previous studies in the xenograft mouse model of HIV-1-induced thymic disruption. Importantly, our studies with this immunologically intact host also showed a dichotomy, related to expression of cognate coreceptors on thymocytes, in the pattern of expression of phenotypically distinct SHIVs within the thymus. Recent studies have addressed phenotype and function of developing T cells in SHIV-infected infants, with an emphasis on defining precursor populations and assessing migratory potential of thymocytes in response to chemokine signals (U. Esser et al., unpublished data). Future studies can aim to determine whether the differential pathology of SHIVSF162P3 and SHIVSF33A infection is related to virus-specific alterations of immunomodulatory proteins (e.g., cytokines and chemokines) in the host. Thus, the pediatric AIDS model in macaques can now be used to address the role of the viral env gene in mechanisms of immunodeficiency, including depletion and dysfunction of thymocytes as well as peripheral blood T lymphocytes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marta Marthas and Kim Schmidt for providing growth rate data for control neonatal macaques; Thomas Famula for providing statistical analysis; Abigail Spinner for performing flow cytometry assays; Christian Leutenegger for real-time RT-PCR; and Christopher Miller, Marta Marthas, and Ross Tarara for advice and encouragement on experimental design and data interpretation. R. A. Reyes acknowledges Helen M. Doughty for literature review and retrieval.

The research in this paper was supported by a grant from the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (51050-25-PG) and utilized resources from the California National Primate Research Center, which is supported by an NIH grant (RR-00169).

REFERENCES

- 1.Auger, I., P. Thomas, V. De Gruttola, D. Morse, D. Moore, R. Williams, B. Truman, and C. E. Lawrence. 1988. Incubation periods for paediatric AIDS patients. Nature 336:575-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba, T. W., V. Liska, A. H. Khimani, N. B. Ray, P. J. Dailey, D. Penninck, R. Bronson, M. F. Greene, H. M. McClure, L. N. Martin, and R. M. Ruprecht. 1999. Live attenuated, multiply deleted simian immunodeficiency virus causes AIDS in infant and adult macaques. Nat. Med. 5:194-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkowitz, R. D., S. Alexander, C. Bare, V. Linquist-Stepps, M. Bogan, M. E. Moreno, L. Gibson, E. D. Wieder, J. Kosek, C. A. Stoddart, and J. M. McCune. 1998. CCR5- and CXCR4-utilizing strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 exhibit differential tropism and pathogenesis in vivo. J. Virol. 72:10108-10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkowitz, R. D., K. P. Beckerman, T. J. Schall, and J. M. McCune. 1998. CXCR4 and CCR5 expression delineates targets for HIV-1 disruption of T cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 161:3702-3710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohm, R. P., Jr., L. N. Martin, B. Davison-Fairburn, G. B. Baskin, and M. Murphey-Corb. 1993. Neonatal disease induced by SIV infection of the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 9:1131-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks, D. G., S. G. Kitchen, C. M. Kitchen, D. D. Scripture-Adams, and J. A. Zack. 2001. Generation of HIV latency during thymopoiesis. Nat. Med. 7:459-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camerini, D., H. P. Su, G. Gamez-Torre, M. L. Johnson, J. A. Zack, and I. S. Chen. 2000. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pathogenesis in SCID-hu mice correlates with syncytium-inducing phenotype and viral replication. J. Virol. 74:3196-3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakrabarti, L. A., T. Ivanovic, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 2002. Properties of the surface envelope glycoprotein associated with virulence of simian-human immunodeficiency virus SHIV(SF33A) molecular clones. J. Virol. 76:1588-1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dehghani, H., C. R. Brown, R. Plishka, A. Buckler-White, and V. M. Hirsch. 2002. The ITAM in Nef influences acute pathogenesis of AIDS-inducing simian immunodeficiency viruses SIVsm and SIVagm without altering kinetics or extent of viremia. J. Virol. 76:4379-4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickover, R. E., M. Dillon, K. M. Leung, P. Krogstad, S. Plaeger, S. Kwok, C. Christopherson, A. Deveikis, M. Keller, E. R. Stiehm, and Y. J. Bryson. 1998. Early prognostic indicators in primary perinatal human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: importance of viral RNA and the timing of transmission on long-term outcome. J. Infect. Dis. 178:375-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etemad-Moghadam, B., D. Rhone, T. Steenbeke, Y. Sun, J. Manola, R. Gelman, J. W. Fanton, P. Racz, K. Tenner-Racz, M. K. Axthelm, N. L. Letvin, and J. Sodroski. 2001. Membrane-fusing capacity of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope proteins determines the efficiency of CD+ T-cell depletion in macaques infected by a simian-human immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 75:5646-5655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etemad-Moghadam, B., D. Rhone, T. Steenbeke, Y. Sun, J. Manola, R. Gelman, J. W. Fanton, P. Racz, K. Tenner-Racz, M. K. Axthelm, N. L. Letvin, and J. Sodroski. 2002. Understanding the basis of CD4(+) T-cell depletion in macaques infected by a simian-human immunodeficiency virus. Vaccine 20:1934-1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grivel, J. C., and L. B. Margolis. 1999. CCR5- and CXCR4-tropic HIV-1 are equally cytopathic for their T-cell targets in human lymphoid tissue. Nat. Med. 5:344-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harouse, J. M., A. Gettie, R. C. Tan, J. Blanchard, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 1999. Distinct pathogenic sequela in rhesus macaques infected with CCR5 or CXCR4 utilizing SHIVs. Science 284:816-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haynes, B. F., M. L. Markert, G. D. Sempowski, D. D. Patel, and L. P. Hale. 2000. The role of the thymus in immune reconstitution in aging, bone marrow transplantation, and HIV-1 infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:529-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirsch, V. M., G. Dapolito, P. R. Johnson, W. R. Elkins, W. T. London, R. J. Montali, S. Goldstein, and C. Brown. 1995. Induction of AIDS by simian immunodeficiency virus from an African green monkey: species-specific variation in pathogenicity correlates with the extent of in vivo replication. J. Virol. 69:955-967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu, M., J. M. Harouse, A. Gettie, C. Buckner, J. Blanchard, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 2003. Increased mucosal transmission but not enhanced pathogenicity of the CCR5-tropic, simian AIDS-inducing simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIV(SF162P3) maps to envelope gp120. J. Virol. 77:989-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Igarashi, T., C. R. Brown, R. A. Byrum, Y. Nishimura, Y. Endo, R. J. Plishka, C. Buckler, A. Buckler-White, G. Miller, V. M. Hirsch, and M. A. Martin. 2002. Rapid and irreversible CD4+ T-cell depletion induced by the highly pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIV(DH12R) is systemic and synchronous. J. Virol. 76:379-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joshi, V. V. 1996. Pathology of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in children. Keio J. Med. 45:306-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keir, M. E., M. G. Rosenberg, J. K. Sandberg, K. A. Jordan, A. Wiznia, D. F. Nixon, C. A. Stoddart, and J. M. McCune. 2002. Generation of CD3+CD8low thymocytes in the HIV type 1-infected thymus. J. Immunol. 169:2788-2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitchen, S. G., and J. A. Zack. 1997. CXCR4 expression during lymphopoiesis: implications for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of the thymus. J. Virol. 71:6928-6934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kourtis, A. P., C. Ibegbu, A. J. Nahmias, F. K. Lee, W. S. Clark, M. K. Sawyer, and S. Nesheim. 1996. Early progression of disease in HIV-infected infants with thymus dysfunction. N. Engl. J. Med. 335:1431-1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kourtis, A. P., C. C. Ibegbu, F. Scinicarrielo, and F. K. Lee. 2001. Effects of different HIV strains on thymic epithelial cultures. Pathobiology 69:329-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krogstad, P., C. H. Uittenbogaart, R. Dickover, Y. J. Bryson, S. Plaeger, and A. Garfinkel. 1999. Primary HIV infection of infants: the effects of somatic growth on lymphocyte and virus dynamics. Clin. Immunol. 92:25-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lackner, A. A., P. Vogel, R. A. Ramos, J. D. Kluge, and M. Marthas. 1994. Early events in tissues during infection with pathogenic (SIVmac239) and nonpathogenic (SIVmac1A11) molecular clones of simian immunodeficiency virus. Am. J. Pathol. 145:428-439. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leutenegger, C. M., J. Higgins, T. B. Matthews, A. F. Tarantal, P. A. Luciw, N. C. Pedersen, and T. W. North. 2001. Real-time TaqMan PCR as a specific and more sensitive alternative to the branched-chain DNA assay for quantitation of simian immunodeficiency virus RNA. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:243-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu, Y., C. D. Pauza, X. Lu, D. C. Montefiori, and C. J. Miller. 1998. Rhesus macaques that become systemically infected with pathogenic SHIV 89.6-PD after intravenous, rectal, or vaginal inoculation and fail to make an antiviral antibody response rapidly develop AIDS. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 19:6-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luciw, P. A., C. P. Mandell, S. Himathongkham, J. Li, T. A. Low, K. A. Schmidt, K. E. Shaw, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 1999. Fatal immunopathogenesis by SIV/HIV-1 (SHIV) containing a variant form of the HIV-1SF33 env gene in juvenile and newborn rhesus macaques. Virology 263:112-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luciw, P. A., E. Pratt-Lowe, K. E. Shaw, J. A. Levy, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 1995. Persistent infection of rhesus macaques with T-cell-line-tropic and macrophage-tropic clones of simian/human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIV). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7490-7494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marthas, M. L., K. K. van Rompay, M. Otsyula, C. J. Miller, D. R. Canfield, N. C. Pedersen, and M. B. McChesney. 1995. Viral factors determine progression to AIDS in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected newborn rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 69:4198-4205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCune, J. M. 1997. Thymic function in HIV-1 disease. Semin. Immunol. 9:397-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nahmias, A. J., W. S. Clark, A. P. Kourtis, F. K. Lee, G. Cotsonis, C. Ibegbu, D. Thea, P. Palumbo, P. Vink, R. J. Simonds, S. R. Nesheim, et al. 1998. Thymic dysfunction and time of infection predict mortality in human immunodeficiency virus-infected infants. J. Infect. Dis. 178:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papiernik, M., Y. Brossard, N. Mulliez, J. Roume, C. Brechot, F. Barin, A. Goudeau, J. F. Bach, C. Griscelli, R. Henrion, et al. 1992. Thymic abnormalities in fetuses aborted from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seropositive women. Pediatrics 89:297-301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pedroza-Martins, L., W. J. Boscardin, D. J. Anisman-Posner, D. Schols, Y. J. Bryson, and C. H. Uittenbogaart. 2002. Impact of cytokines on replication in the thymus of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from infants. J. Virol. 76:6929-6943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pizzo, P. A., and C. M. Wilfert. 1998. Pediatric AIDS: the challenge of HIV infection in infants, children, and adolescents, 3rd ed. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md.

- 36.Rosenzweig, M., M. Connole, A. Forand-Barabasz, M. P. Tremblay, R. P. Johnson, and A. A. Lackner. 2000. Mechanisms associated with thymocyte apoptosis induced by simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Immunol. 165:3461-3468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scarlatti, G., E. Tresoldi, A. Bjorndal, R. Fredriksson, C. Colognesi, H. K. Deng, M. S. Malnati, A. Plebani, A. G. Siccardi, D. R. Littman, E. M. Fenyo, and P. Lusso. 1997. In vivo evolution of HIV-1 co-receptor usage and sensitivity to chemokine-mediated suppression. Nat. Med. 3:1259-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor, J. R., Jr., K. C. Kimbrell, R. Scoggins, M. Delaney, L. Wu, and D. Camerini. 2001. Expression and function of chemokine receptors on human thymocytes: implications for infection by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:8752-8760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang, L., T. He, A. Talal, G. Wang, S. S. Frankel, and D. D. Ho. 1998. In vivo distribution of the human immunodeficiency virus/simian immunodeficiency virus coreceptors: CXCR4, CCR3, and CCR5. J. Virol. 72:5035-5045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]