Abstract

Germanium biotite (GB) is an aluminosilicate mineral containing 36 ppm germanium. The present study was conducted to better understand the effects of GB on immune responses in a mouse model, and to demonstrate the clearance effects of this mineral against Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) in experimentally infected pigs as an initial step towards the development of a feed supplement that would promote immune activity and help prevent diseases. In the mouse model, dietary supplementation with GB enhanced concanavalin A (ConA)-induced lymphocyte proliferation and increased the percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes. In pigs experimentally infected with PRRSV, viral titers in lungs and lymphoid tissues from the GB-fed group were significantly decreased compared to those of the control group 12 days post-infection. Corresponding histopathological analyses demonstrated that GB-fed pigs displayed less severe pathological changes associated with PRRSV infection compared to the control group, indicating that GB promotes PRRSV clearance. These antiviral effects in pigs may be related to the ability of GB to increase CD3+CD8+ T lymphocyte production observed in the mice. Hence, this mineral may be an effective feed supplement for increasing immune activity and preventing disease.

Keywords: germanium biotite, immune enhancement, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus

Introduction

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), an Arterivirus, emerged in the late 1980s in the United States and Europe [24]. It quickly spread worldwide and became enzootic among pig populations in most countries [24]. The virus strongly modulates host immune responses and changes host gene expression patterns. PRRSV inhibits the production of key cytokines, such as interferon (IFN)-α [2,3], and may induce the expression of regulatory cytokines including interleukin (IL)-10 [20]. Moreover, the appearance of neutralizing antibodies is delayed in pigs infected with PRRSV [4,16,23] and these animals are more prone to develop concomitant infectious diseases [10,19]. Data from these and other studies indicate that PRRSV causes immunosuppression in the affected pigs [5,15]. Therefore, strengthening the host defense mechanisms may be important for controlling PRRSV infection.

Germanium biotite (GB) is an aluminosilicate mineral that contains 36 ppm germanium. This compound possesses a number of biological activities that are beneficial for animal health, especially immune function and host defense. A previous study reported that GB enhances the production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in mouse spleen lymphocyte [11]. Continuous ingestion of the mineral also increases phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-induced cytokine expression and enhances antibody production in mice in a dose-dependent manner [9]. Moreover, dietary supplementation with GB expedites the clearance of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) in experimentally infected pigs [9] as well as bovine herpesvirus type 1 (BHV1) clearance from experimentally infected calves [12]. These findings suggest that GB as a feed supplement can potentially protect against respiratory viral diseases through the potent stimulation of non-specific immune responses. However, the underlying immunological mechanisms remain unclear and anti-PRRSV effects of the mineral have not yet been examined.

The purpose of the present study was to better understand the effects of GB on immune responses in a mouse model, and to demonstrate the effects of this mineral on PRRSV clearance in experimentally infected pigs. Lymphocyte proliferation and changes in lymphocyte subpopulations in the mice were evaluated. In addition, PRRSV titers in lung and various lymphoid tissues of experimentally infected pigs were measured. This investigation was performed as an initial step towards the development of a feed supplement that increases immune activity and helps prevent diseases.

Materials and Methods

Source and composition of the GB feed supplement

GB used in this study as a feed supplement was provided by Seobong Biobestech (Korea). The supplement was composed of silicon dioxide (SiO2, 61.90%), aluminum oxide (Al2O3, 23.19%), iron oxide (Fe2O3, 3.97%), sodium oxide (Na2O, 3.36%), and 36 ppm germanium.

Animals and animal care

Specific pathogen-free female 6-week-old BALB/c mice (DBL, Korea) were used to investigate the effects of GB on host immune responses. The mice were randomly divided into three groups of eight mice each. The control group received a commercial, nutritionally complete, extruded dry rodent feed (Superfeed, Korea). The experiment groups received the same rodent feed supplemented with either 0.1% (0.1% GB-fed group) or 0.3% (w/w) GB (0.3% GB-fed group).

Conventional 6-week-old pigs (Korea) were used to evaluate GB-mediated clearance of PRRSV. Prior to purchase, sera from the littermates were tested and the animals were confirmed to be negative for antibodies against PRRSV using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (IDEXX Laboratories, USA). The pigs were randomly divided into two groups of six pigs each. The control group received a commercial and nutritionally complete swine feed (Daehan Livestock and Feed, Korea). The experiment group received the same swine feed supplemented with 0.3% (w/w) GB.

All animals were housed in an air-controlled separate room, and allowed free access to tap water and their particular diets. All animal procedures were approved (no. CNU IACUC-YB-2010-1) by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chonnam National University (Korea).

Isolation of mouse lymphocytes

The mice were fed the control or experimental diets for 2 weeks. The animals were then sacrificed and the spleen was collected. The spleens were aseptically removed with scissors and forceps, placed in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and single-cell suspensions were prepared by pushing the tissue through a 40-µm nylon mesh (BD Biosciences, USA). Erythrocytes in the cell mixture were destroyed by incubation with Tris-NH4Cl. The lymphocytes were washed with PBS twice prior to resuspension in complete medium consisting of RPMI-1640 medium (Lonza, Switzerland) containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, USA) and 2% (v/v) antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Lonza, Switzerland). Live cells were detected by staining with trypan blue.

Measurement of lymphocyte proliferation in mice

Mouse lymphocyte proliferation was measured as previously described [8]. Cell suspensions were diluted to a final concentration of 3 × 106 cells/mL in complete medium. One hundred µL of the cell suspension and 100 µL complete medium with or without 5 µg/mL concanavalin A (ConA; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) or 50 µg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma-Aldrich) were added into each well of a 96-well plate (SPL Life Sciences, Korea). The cultures were set up in duplicate. After a 48-h incubation at 37℃ in a 5% CO2 incubator, 20 µL of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, 5 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were added to each well and the plate was incubated for another 4 h. The plate was then centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min and the supernatants were discarded. A total of 200 µL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added to each well and the plate was shaken until the formazan crystals dissolved. The absorbance of each sample was read using a microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Labsystems, Finland) at 540 nm.

Evaluation of mouse T lymphocyte subpopulations

Immunofluorescent staining was performed to measure the CD3+CD4+ T and CD3+CD8+ T cell populations in the spleen of each sacrificed mouse as previously described [7]. Lymphocytes were stained with both phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated hamster anti-mouse CD3 (BD Biosciences, USA) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD4 (BD Biosciences, USA) antibodies, or FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD8 antibody (BD Biosciences, USA). After incubating for 30 min at room temperature in the dark, the cells were washed twice with PBS and the T lymphocyte subpopulations were analyzed using a FACSort flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA). Viable lymphocytes were gated according to forward and side-scatter characteristics (FSC/SSC), and 10,000 events were analyzed to evaluate FITC- and PE-positive signals. Results for each T lymphocyte subpopulation are expressed as percentages of events in the FSC/SSC lymphocyte gate.

Experimental PRRSV infection of pigs

All pigs were fed the experimental or control diet for 2 weeks before being experimentally infected with the virus. PRRSV was obtained from the Animal, Plant and Fisheries Quarantine and Inspection Agency (Korea). For the inoculum, a virus stock was propagated in confluent monolayers of MARC-145 cells as previously described [13]. Five mL of the viral culture (1 × 106.1 50% tissue culture infective dose/mL) was administered intranasally through each nostril of the pigs. The rectal temperatures of pigs were measured at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 14, 21, 24, and 28 days post-infection (DPI). Three pigs from each group were randomly sacrificed at 12 and 28 DPI. Lung and lymphoid tissues (bronchial lymph node, tonsil, and thymus) were then collected.

Measurement of viral titers in tissues from PRRSV-infected pigs

Lung and lymphoid tissues were homogenized (10%, w/v) in minimum essential medium alpha modification (alpha-MEM; Welgene, Korea) containing 2% (v/v) antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Lonza, Switzerland). The tissues were homogenized using a Tissue Tearor homogenizer (Biospec Products, USA) and then centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 30 min at 4℃. The supernatant was passed through a nonpyrogenic syringe filter with 0.2-µm pores (Pall Corporation, USA). The resulting suspensions were used as inocula to determine the viral titer using a plaque assay [14]. Briefly, each suspension was serially diluted 10-fold in alpha-MEM (Welgene, Korea) containing 2% (v/v) antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Lonza, Switzerland). One mL of each dilution was used to inoculate confluent monolayers of MARC-145 cells prepared in a 6-well plate (SPL Life Sciences). The cells were incubated with the inoculum in 5% CO2 at 37℃ for 1 h with manual rocking every 10 min. The inoculum was then replaced with an overlay medium consisting of alpha-MEM (Welgene, Korea) supplemented with 5% (v/v) FBS (Lonza, Switzerland), 2% (v/v) antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Lonza, Switzerland), and 1.6% (w/v) carboxymethylcellulose sodium salt (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The cells were further incubated for up to 5 days in 5% CO2 at 37℃ until plaques were clearly observed. After overnight fixation of the monolayers in 10% (v/v) neutral buffered formalin, the supernatant was removed and 1% (w/v) crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added to each well. The plates were kept at room temperature for 30 min, washed with tap water until the excess crystal violet was removed, inverted over absorbent paper, and allowed to dry. The plaques were counted and viral titers are expressed as plaque forming unit (pfu)/gram tissue. Each sample was tested in duplicate.

Histopathologic analysis of tissues from PRRSV-infected pigs

Lung and lymphoid tissues were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, cut into sections (5-µm thick), and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histopathological examination. Microscopic lesions were evaluated using a previously described scoring system [18]. In sections of lung, the presence and severity of type 2 pneumocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia, alveolar septal infiltration by inflammatory cells, peribronchial lymphoid hyperplasia, volume of alveolar exudate, and degree of inflammation in the lamina propria of the bronchi and bronchioles were scored on a scale ranging from 0~6 (0, normal; 1, mild and multifocal; 2, mild and diffuse; 3, moderate and multifocal; 4, moderate and diffuse; 5, severe and multifocal; or 6, severe and diffuse). Sections of lymphoid tissues were evaluated for lymphoid depletion using a scale ranging from 0~3 (0, normal; 1, mild lymphoid depletion with loss of overall cellularity; 2, moderate lymphoid depletion; and 3, severe lymphoid depletion with loss of lymphoid follicular structure) and the presence of inflammation with a scale ranging from 0~3 (0, normal; 1, mild histiocytic-to-granulomatous inflammation; 2, moderate histiocytic-to-granulomatous inflammation; and 3, severe histiocytic-to-granulomatous inflammation with replacement of follicles). Scores representing the microscopic lesion severity in sections of lymphoid tissues were calculated as the sum of the individual scores for both parameters. All histological evaluations were performed in a blinded manner.

Statistical analyses

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's multiple comparison tests was used to analyze results from the mouse model. Student's t-test was performed to analyze data from the swine experiments. A Mann-Whitney U test (nonparametric test) was also used to compare microscopic lesion scores (ordinal data) for tissues from the experimentally PRRSV-infected pigs. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 software (SPSS, USA). P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Impact of GB on lymphocyte proliferation in mice

Lymphocytes were incubated with or without mitogens (ConA or LPS) and lymphocyte proliferation was measured as the OD540 value using an MTT assay. Lymphocyte proliferation in response to ConA was significantly enhanced (p < 0.05) in the GB-fed groups (0.745 ± 0.084 and 0.762 ± 0.093 for the 0.1% and 0.3% GB-fed groups, respectively) compared to the control group (0.650 ± 0.044). However, proliferation of the unstimulated or LPS-treated lymphocytes did not vary among the groups (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effects of germanium biotite (GB) on lymphocyte proliferation in mice. Lymphocytes were with or without mitogens (ConA or LPS), and lymphocyte proliferation was measured as OD540 using an MTT assay. Lymphocyte proliferation in response to ConA was significantly enhanced in the GB-fed mice compared to the control group (*p < 0.05). However, proliferation of the unstimulated or LPS-treated lymphocytes did not differ among the groups. Data are presented the mean ± SD (n = 8).

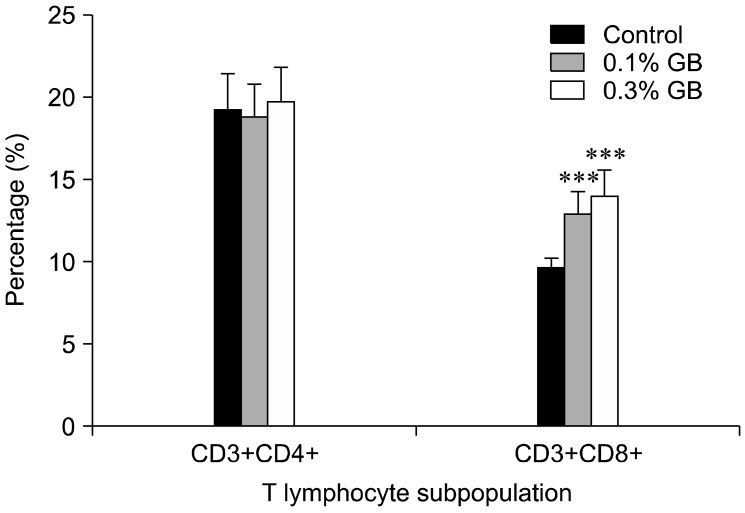

Effects of GB on T lymphocyte subpopulations in mice

Percentages of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes in spleens from the GB-fed groups (12.82 ± 1.39% and 13.96 ± 1.60% for the 0.1% and 0.3% GB-fed groups, respectively) were significantly increased (p < 0.001) compared to those observed in the control group (9.63 ± 0.61%). However, no significant differences in the percentages of CD3+CD4+ T lymphocytes in the spleen were observed among the groups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of GB on T lymphocyte subpopulation ratios in mice. The percentage of CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes in the spleens of GB-fed mice was significantly increased compared to that observed for the control group (***p < 0.001). However, no significant difference in the percentage of spleen CD3+CD4+ T lymphocytes was observed among the groups. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 8).

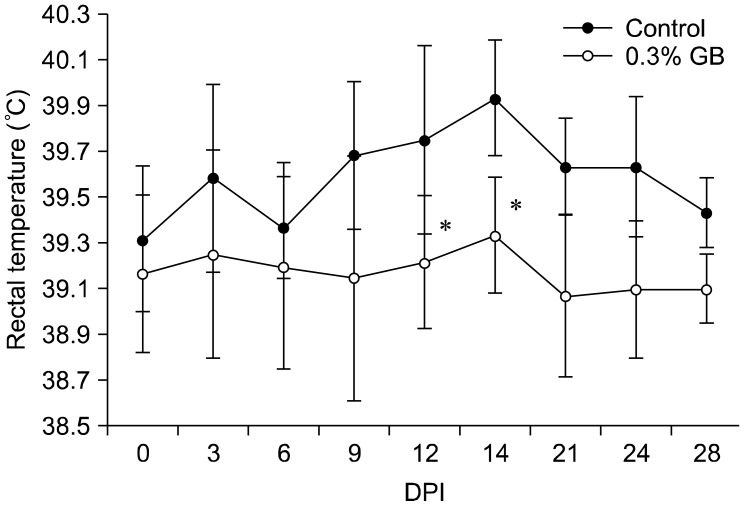

Rectal temperature of PRRSV-infected pigs

Mean rectal temperature of the pigs gradually increased up to 14 DPI. The temperature subsequently declined until the end of the experiment. Rectal temperature of the GB-fed group was lower than that of the control group throughout the experimental period. In particular, a significant difference in rectal temperature (p < 0.05) was observed between the groups at 12 and 14 DPI (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of GB on rectal temperature in pigs experimentally infected with PRRSV. Mean rectal temperature of the pigs gradually increased up to 14 days post-infection (DPI) after which the temperature declined until the end of the experiment. Rectal temperature of the 0.3% GB-fed group was lower than that of the control group throughout the experimental period. In particular, the difference in rectal temperature between the two groups was statistically significant at 12 and 14 DPI (*p < 0.05). Data are presented as the mean ± SD (0 ~ 12 DPI: n = six in each group, 14~28 DPI: n = three in each group).

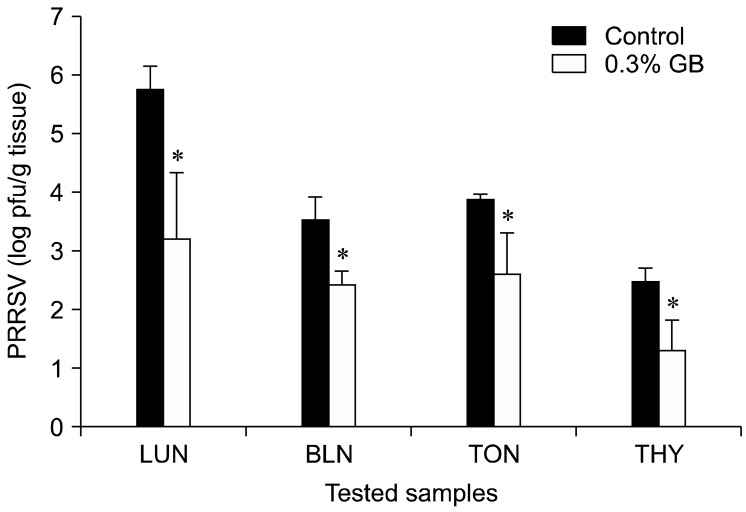

Viral titer of tissues from PRRSV-infected pigs

At 12 DPI, viral titer of the lungs was significantly decreased (p < 0.05) in the GB-fed group (3.19 ± 1.14 log pfu/g tissue) compared to the control group (5.73 ± 0.41 log pfu/g tissue). Moreover, viral titers of the lymphoid tissues including bronchial lymph node, tonsil, and thymus were also significantly decreased (p < 0.05) in the GB-fed group compared to the control group (Fig. 4). However, viral titers of lungs and lymphoid tissues from both groups were almost under the limit of detection (10 pfu/g tissue) at 28 DPI (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Effects of GB on PRRSV clearance in experimentally infected pigs. At 12 DPI, the viral titer of lung (LUN) tissues from the 0.3% GB-fed pigs was significantly decreased compared that for the control group (*p < 0.05). Moreover, viral titers of lymphoid tissues including bronchial lymph node (BLN), tonsil (TON), and thymus (THY) were significantly decreased in the 0.3% GB-fed animals compared to the control group (*p < 0.05). Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3).

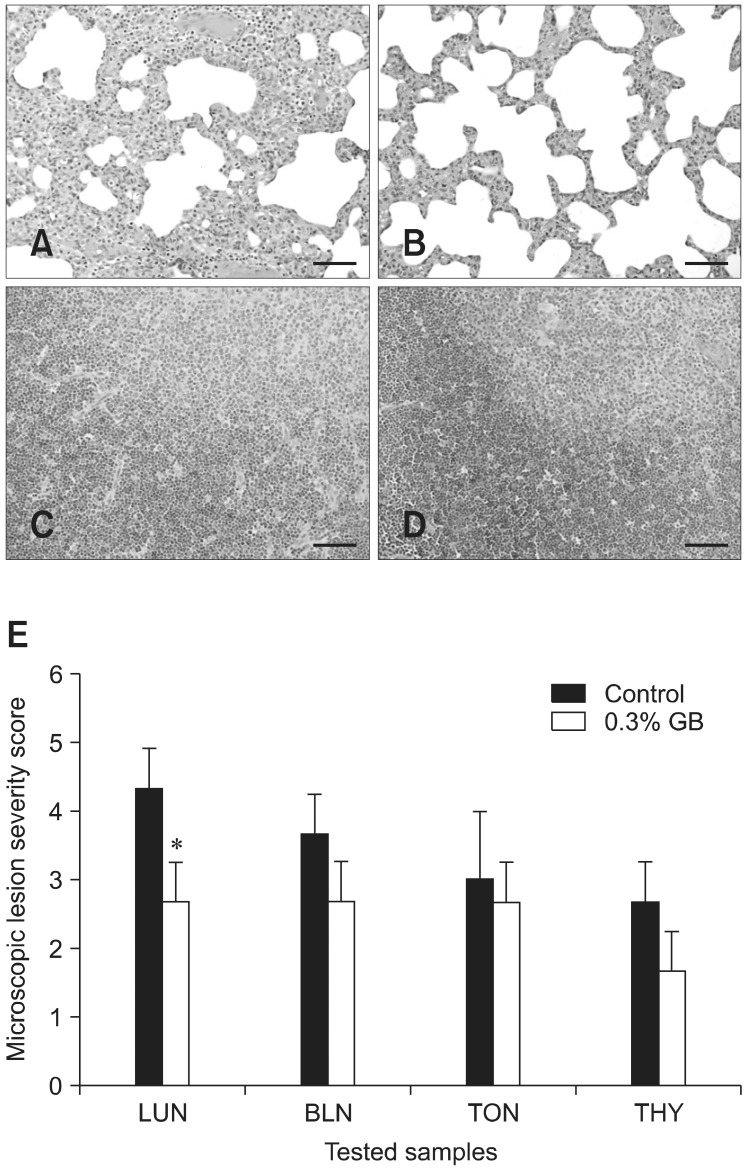

Histopathologic analysis of tissues from PRRSV-infected pigs

At 12 DPI, the experimentally PRRSV-infected pigs developed interstitial pneumonia characterized by type 2 pneumocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia along with alveolar wall thickening by macrophages and lymphocytes. These lesions were milder in the GB-fed group (Fig. 5B) compared to the control group (Fig. 5A). Additionally, lymphoid depletion was less severe in the GB-fed animals, and clearer separation between the cortex and medulla of the thymus was observed (Fig. 5D) compared to the control group (Fig. 5C). Scores for microscopic lesions in the collected tissue samples are shown in Fig. 5E. Scores for the lung microscopic lesions in the GB-fed pigs were significantly decreased compared to ones for the control group (p < 0.05). Moreover, scores for the lymphoid microscopic lesions in the GB-fed group were also lower compared to those for the control group although this difference was not significant. Lesions in the lungs and lymphoid tissues of both groups were almost fully healed at 28 DPI (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Histopathological features of lung and thymus, and microscopic lesion scores for tissue samples from PRRSV-infected pigs. Pigs fed 0.3% GB (B) had milder cases of interstitial pneumonia at 12 DPI (based on lung histopathological features) compared to the control animals (A). Additionally, lymphoid depletion was less severe in the 0.3% GB-fed group, and clearer separation between the cortex and medulla of the thymus (D) compared to the control group (C) was observed. Lung (LUN) microscopic lesion scores for pigs fed 0.3% GB were significantly decrease compared to those for the control group (*p < 0.05). Moreover, microscopic lesion scores for the lymphoid tissues [bronchial lymph node (BLN), tonsil (TON), and thymus (THY)] from the 0.3% GB-fed group were lower than those for the control group although this difference was not significant. Scale bar = 100 µm. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3).

Discussion

In the present study, dietary supplementation with GB enhanced ConA (T-cell mitogen)-induced lymphocyte proliferation in mice. This finding was consistent with data from our previous study showing that GB markedly increases the ability of PHA (a T-cell mitogen) to induce cytokine expression in mice [9]. Furthermore, the CD3+CD8+ T lymphocyte ratio was significantly increased in the spleens of mice fed GB compared to those of the control group. In contrast, the CD3+CD4+ T lymphocyte ratio did not vary between the groups in the present study. These results imply that dietary GB supplementation enhances immune responses and the proliferation of T lymphocytes, especially CD3+CD8+ cells. Previous studies have demonstrated that aluminosilicate, the main component of GB, acts as a non-specific immunostimulant similar to superantigens [1,22], a class of extremely potent T cell mitogens [21]. It is also well known that germanium activates T lymphocytes, especially cytotoxic T cells [6]. Collectively, observations from the present study and data from the literature indicate that dietary supplementation with GB mainly affects CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes.

In the current investigation, dietary supplementation with GB alleviated high fever in pigs experimentally infected with PRRSV throughout the experimental period. Moreover, the viral titer for lungs from the GB-fed group was significantly decreased at 12 DPI compared to that for the control group; however, viral titers for both groups were under the limit of detection at 28 DPI. Similar trends were also observed in all tested lymphoid tissues. Histopathological analysis also revealed that GB supplementation resulted in less severe abnormal changes associated with PRRSV infection compared to the control group. These results imply that dietary supplementation with GB promotes PRRSV clearance in experimentally infected pigs. This is consistent with findings from our previous studies showing that GB enhances the clearance of respiratory viruses such as PCV2 and BHV1 in experimentally infected pigs and calves [9,12]. It is generally accepted that CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes inhibit the replication of intracellular pathogens like viruses by secreting soluble mediators that interfere with pathogen replication and/or induce the death of infected cells [17]. Therefore, the antiviral activities of GB may be related to the CD3+CD8+ T lymphocyte stimulatory effects observed in the mice.

In summary, findings from the present investigation suggest that dietary supplementation with GB primarily stimulates CD3+CD8+ T lymphocyte proliferation in mice and expedites the clearance of PRRSV in experimentally infected pigs. Hence, GB may serve as a feed supplement that promotes immune activity and helps prevent disease. However, the effects of GB on immune responses in swine were not assessed in the present study. Additionally, the exact mechanisms underlying virus clearance promoted by GB were not identified. Further experiments need to be performed to understand effects of GB on immune responses and virus clearance in pigs. PRRSV clearance following GB administration should also be measured in pigs with naturally occurring cases of PRRS.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Technology Development Program for Agriculture and Forestry, Ministry for Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Korea. A graduate fellowship was also provided by the Korean Ministry of Education and Human Resources Development through the Brain Korea 21 Project.

References

- 1.Aikoh T, Tomokuni A, Matsukii T, Hyodoh F, Ueki H, Otsuki T, Ueki A. Activation-induced cell death in human peripheral blood lymphocytes after stimulation with silicate in vitro. Int J Oncol. 1998;12:1355–1359. doi: 10.3892/ijo.12.6.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albina E, Carrat C, Charley B. Interferon-alpha response to swine arterivirus (PoAV), the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1998;18:485–490. doi: 10.1089/jir.1998.18.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buddaert W, Van Reeth K, Pensaert M. In vivo and in vitro interferon (IFN) studies with the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;440:461–467. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5331-1_59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Díaz I, Darwich L, Pappaterra G, Pujols J, Mateu E. Immune responses of pigs after experimental infection with a European strain of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:1943–1951. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80959-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drew TW. A review of evidence for immunosuppression due to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Vet Res. 2000;31:27–39. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirayama C, Suzuki H, Ito M, Okumura M, Oda T. Propagermanium: a nonspecific immune modulator for chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:525–532. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung BG, Ko JH, Cho SJ, Koh HB, Yoon SR, Han DU, Lee BJ. Immune-enhancing effect of fermented Maesil (Prunus mume Siebold & Zucc.) with probiotics against Bordetella bronchiseptica in mice. J Vet Med Sci. 2010;72:1195–1202. doi: 10.1292/jvms.09-0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung BG, Ko JH, Lee BJ. Dietary supplementation with a probiotic fermented four-herb combination enhances immune activity in broiler chicks and increases survivability against Salmonella Gallinarum in experimentally infected broiler chicks. J Vet Med Sci. 2010;72:1565–1573. doi: 10.1292/jvms.10-0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung BG, Toan NT, Cho SJ, Ko JH, Jung YK, Lee BJ. Dietary aluminosilicate supplement enhances immune activity in mice and reinforces clearance of porcine circovirus type 2 in experimentally infected pigs. Vet Microbiol. 2010;143:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung K, Renukaradhya GJ, Alekseev KP, Fang Y, Tang Y, Saif LJ. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus modifies innate immunity and alters disease outcome in pigs subsequently infected with porcine respiratory coronavirus: implications for respiratory viral co-infections. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:2713–2723. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.014001-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung M, Cha SB, Shin SW, Lee WJ, Shin MK, Yoo A, Yoo HS. The effects of Germanium biotite on the adsorptive and inhibition of growth abilities against E. coli and Salmonella spp. in vitro. Korean J Vet Res. 2012;52:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung M, Jung BG, Cha SB, Shin MK, Lee WJ, Shin SW, Lee JA, Jung YK, Lee BJ, Yoo HS. The effects of germanium biotite supplement as a prophylactic agent against respiratory infection in calves. Pak Vet J. 2012;32:319–324. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HS, Kwang J, Yoon IJ, Joo HS, Frey ML. Enhanced replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus in a homogeneous subpopulation of MA-104 cell line. Arch Virol. 1993;133:477–483. doi: 10.1007/BF01313785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim WI, Kim JJ, Cha SH, Yoon KJ. Different biological characteristics of wild-type porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses and vaccine viruses and identification of the corresponding genetic determinants. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1758–1768. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01927-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mateu E, Diaz I. The challenge of PRRS immunology. Vet J. 2008;177:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meier WA, Galeota J, Osorio FA, Husmann RJ, Schnitzlein WM, Zuckermann FA. Gradual development of the interferon-γ response of swine to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection or vaccination. Virology. 2003;309:18–31. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moser M, Leo O. Key concepts in immunology. Vaccine. 2010;28(Suppl 3):C2–C13. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Opriessnig T, Thacker EL, Yu S, Fenaux M, Meng XJ, Halbur PG. Experimental reproduction of postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome in pigs by dual infection with Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and porcine circovirus type 2. Vet Pathol. 2004;41:624–640. doi: 10.1354/vp.41-6-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renukaradhya GJ, Alekseev K, Jung K, Fang Y, Saif LJ. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus-induced immunosuppression exacerbates the inflammatory response to porcine respiratory coronavirus in pigs. Viral Immunol. 2010;23:457–466. doi: 10.1089/vim.2010.0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suradhat S, Thanawongnuwech R. Upregulation of interleukin-10 gene expression in the leukocytes of pigs infected with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:2755–2760. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomai M, Kotb M, Majumdar G, Beachey EH. Superantigenicity of streptococcal M protein. J Exp Med. 1990;172:359–362. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ueki A, Yamaguchi M, Ueki H, Watanabe Y, Ohsawa G, Kinugawa K, Kawakami Y, Hyodoh F. Polyclonal human T-cell activation by silicate in vitro. Immunology. 1994;82:332–335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon KJ, Wu LL, Zimmerman JJ, Hill HT, Platt KB. Antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) infection in pigs. Viral Immunol. 1996;9:51–63. doi: 10.1089/vim.1996.9.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmerman J, Benfield DA, Murtaugh MP, Osorio F, Stevenson GW, Tottemorell M. PRRS virus (Porcine Arterivirus) In: Straw BE, Zimmerman JJ, D'Allaire S, Taylor DJ, editors. Diseases of Swine. 9th ed. Ames: Blackwell; 2006. pp. 387–417. [Google Scholar]