Abstract

This paper describes the mobility patterns, rural-urban linkages and household structures for a low-income neighbourhood on the outskirts of Mombasa, Kenya’s main port, and a rural settlement 60 kilometres away. Drawing on interviews with a sample of mothers resident in each location, it documents their perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of rural and urban life, and shows the continuous interchange between the two areas. It also highlights how most rural to urban migrants are familiar with urban environments before moving and how, having moved, many maintain strong rural ties. The ways in which households are split across rural and urban areas is influenced by intra-household relations and by household efforts to balance the income-earning opportunities in town, the relatively low cost of living in rural areas and future family security. This produces dramatic differences between and among rural and urban mothers and suggests a need for policy makers and planners to recognize diversity and to build upon complex livelihood strategies that span the rural-urban divide.

I. INTRODUCTION

THE MOST RECENT UN statistics suggest that sub-Saharan Africa continues to have high urban growth rates, although for many nations the scale of growth during the 1990s is unclear because there are no recent census data. That many cities have continued to expand despite sustained recession and a rapid rise in urban poverty has important implications for low-income residents’ health care, education and food provision.(1) In recent years, these factors have contributed to a slowdown in the reduction of urban under-five mortality rates, and even a rise in these rates.(2)

Recognition of the complex and inter-related nature of urban poverty and ill-health has led to a general shift in approaches to urban health from “top-down” disease-targeted projects to “bottom-up” process-oriented programmes aimed at improving the overall well-being of citizens.(3) This shift is reflected in other sectors and has highlighted the need for urban planners to consider a range of socio-demographic factors influencing the lives of urban residents, including rural-urban interdependencies, changes in dependency ratios in the urban setting and urban social support networks.(4) Although these processes have attracted increasing attention in recent years, the specific involvement of women remains relatively poorly documented.(5) Gender selectivity in mobility, the “feminization” of rural-urban migration streams and the central role that wives and mothers play in the well-being of all household members suggest that an improved understanding is needed.

In Kenya’s Coast Province, population movement has generally been eastwards and into urban areas along the Indian Ocean coast.(6) As a major employment centre, Mombasa city continues to attract high volumes of in-migrants who generally have been described as being 15-64 years old, male (single or married), with at least primary level of education.(7) There is little quantitative data on migration below the district level and none on community “circular” (or temporary) mobility and rural-urban ties. As in other areas in Africa, women’s movement is described as largely “associational”, or undertaken together with family members.(8)

In this paper, we draw on quantitative and qualitative data to compare the demographic composition of a rural and a low-income urban community, and to describe and explain the mobility patterns and rural-urban linkages maintained by residents in both areas. The data were collected as part of a broader study exploring rural and urban mothers’ treatment-seeking behaviour for child illnesses. The focus is on Mijikenda mothers with children under the age of ten; the Mijikenda are the dominant ethnic group in coastal Kenya, and primary responsibility for the day-to-day care of young children falls largely on their mothers.

II. STUDY AREAS AND METHODOLOGY

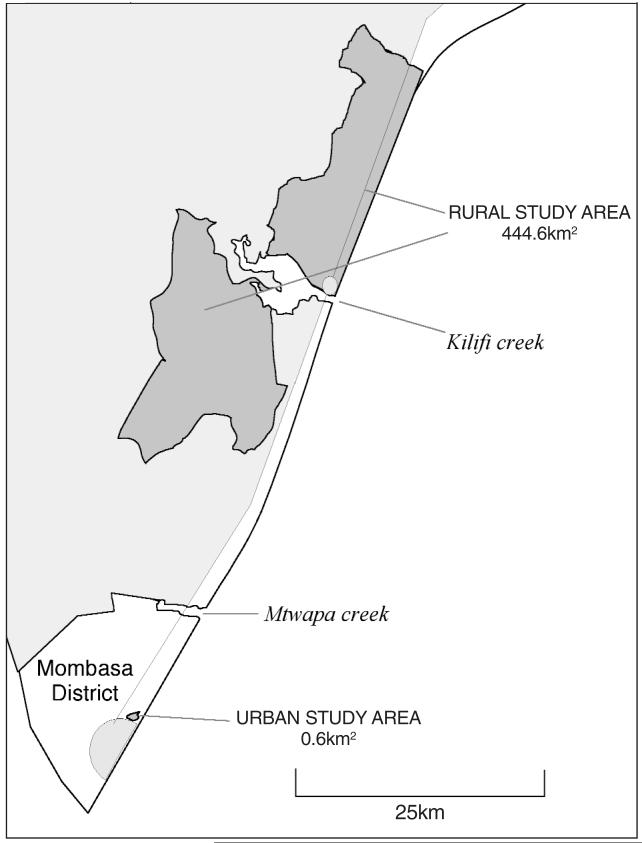

TWO LOW-INCOME settlements were selected for this study: one in Mombasa, the second largest city in Kenya, and one 60 kilometres away in a rural area of Kilifi district (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The study areas

The rural study area

The population consists largely of Mijikenda farmers, who supplement subsistence incomes with cash crops and remittances from family members working in the nearby urban centres of Kilifi, Malindi and Mombasa. The Mijikenda family system is patriarchal and polygamous. The geography, anthropology and disease ecology of the area have been described in detail elsewhere.(9) Poverty is widespread but there are no data on the proportion of individuals falling below an absolute poverty line.

The urban study area

The 0.6 square kilometre study area, Ziwa la Ng’ombe, lies on the northern outskirts of Mombasa. In 1992 and 1994, approximately one-third of city residents fell below an absolute poverty line.(10) The majority of the urban poor live in identifiable geographical areas.(11) Ziwa la Ng’ombe has the densely-populated housing characteristics common to low-income areas of Mombasa and other East African towns. Household incomes are derived largely from in and around the city and are often linked to tourism. The history, geography, demography and political organization of the city have been described elsewhere,(12) with several of these studies offering insights into residents’ lives.

a. Mapping, enumeration and mothers’ survey

The position of every household in both study areas was recorded using hand-drawn maps, and these maps were used to census residents in each household.(13) The names, sex, ethnic group and date of birth of every resident in each household was recorded. A total of 82,594 and 14,885 people were enumerated in the rural and urban study areas, respectively. Women identified as having the prime responsibility for at least one resident child under the age of ten (whether or not they gave birth to the child(ren)) were registered as “mothers”.

Giriama, Chonyi and Kauma (GCK) mothers (sub-groups of the Mijikenda peoples) were randomly selected from the rural census, and a sample who had never lived in an urban area were identified through re-interview.(14) All urban resident GCK mothers were sampled directly from the census. Data collected from the rural and urban samples (n=284 and 248, respectively) included a migration history for each mother, circulation patterns over the last 12 months (or since in-migration to the current household of residence),(15) overnight visitors to the household over the last 12 months, and basic socioeconomic characteristics. The number of individuals other than nuclear family members resident in the current household that mothers (and their partners) were supporting, and where these individuals were living, was also recorded.

b. In-depth interviews

Semi- and unstructured individual and group interviews involving 128 rural and 95 urban mothers were designed to enrich the survey findings. Most (83 per cent) of the participating mothers were purposely selected from the survey samples by marital, employment and educational status. Maternal mobility patterns were explored principally through discussions of the advantages and disadvantages of living in rural and urban areas, reasons for and against maintaining rural homesteads, and life histories.

III. POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD STRUCTURES

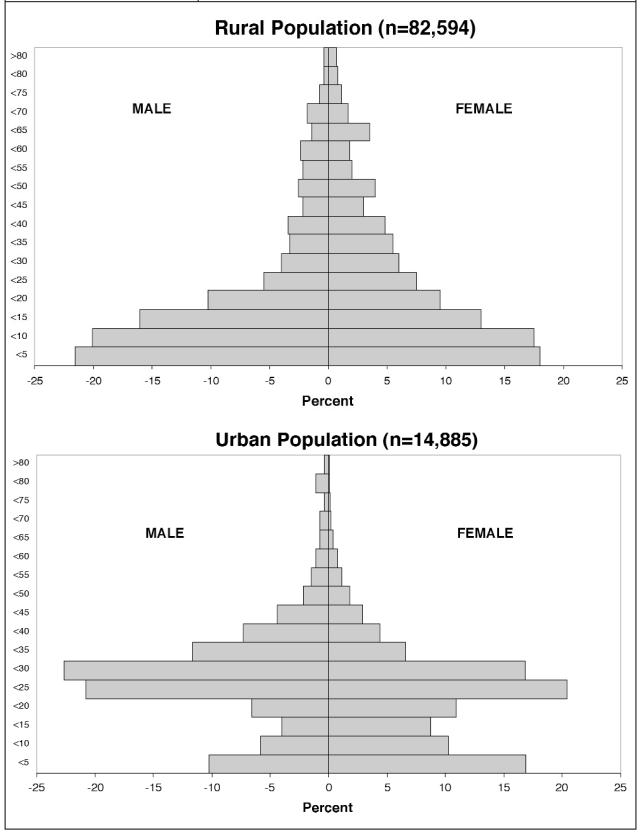

THE URBAN AREA was far more densely populated (25,085 people/square kilometre) than the rural area (186 people/square kilometre). Most rural residents (99 per cent) were Mijikenda, principally of the GCK sub-groups (98 per cent). The Mijikenda were the dominant people in the urban population (43 per cent) but over 22 ethnic groups were represented in the 0.6 square kilometre area. Thirty-one per cent of the urban population were GCK. The rural and urban study area population pyramids (see Figures 2 and 3) illustrate highly significant differences in the two populations’ age-sex structures. The urban population had a far higher ratio of males to females (163:100 as compared to 86:100; chi-square =1198; p<0.00001) and a higher proportion of 20-35 year-olds (chi-square = 7765.81; p< 0.00001).

Figures 2 & 3.

Population age-sex structures

Rural and urban residents were enumerated in 7,788 and 6,458 households, respectively. Rural households typically consisted of one or more owner-occupied houses built within a compound, with a communal shamba (farm). In the urban area, a median of four households were living in each identifiable building, with 67 per cent of households occupying only one room. Rural households were generally larger than urban households (with a median of nine (dq 8) and two (dq 2) residents, respectively). Median urban household size is affected by the large proportion (45 per cent) of people living alone, the majority (88 per cent) of whom were men. When all single-person households are excluded from analysis, the median size increases to three (dq 2). Further differences in rural and urban household form included: the proportion headed by women; the proportion with no resident males over the age of 15 or 20; and the proportion with resident children under the ages of 15 and 10 (see Table 1). These differences are observed whether or not single-person households are included.

Table 1.

Comparing rural and urban household composition

| (A) - % all households | (B) -% non single-person households |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural (n=7788) |

Urban (n=6047)* |

X2 | Rural (n=7651) |

Urban (n=3346) |

X2 | |

| Female-headed | 30 | 24 | 61.3*** | 30 | 26 | 17.9*** |

| Female adults only | ||||||

| No males > 15 years | 16 | 12 | 44.1*** | 15 | 10 | 49.3*** |

| No males > 20 years | 20 | 15 | 57.9*** | 20 | 12 | 101.9*** |

| Include children | ||||||

| Aged <15 years | 84 | 28 | 4428.9*** | 88 | 51 | 1784.8*** |

| Aged <10 years | 80 | 26 | 4034.0*** | 84 | 47 | 1604.8*** |

p < 0.00001

96% total peri-urban households; 4% (n=412) not included because age and/or sex information missing for at least one member of the household.

The overall differences in rural and urban household form suggest that the situation of women in the two study areas will differ significantly. While women’s perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of life in rural and (low-income) urban areas support this suggestion (see Table 2), experiences are also highly diverse within each area. The complexity of household form and the centrality of conjugal and other relationships in shaping women’s experiences have been described in detail elsewhere.(16) But, briefly, women highlighted the important intersecting influences as being:

whether “extended” households are “united” (nuclear households assist each other with everyday needs, or in times of crisis or celebration) or “divided” (nuclear households live on one compound but live entirely separate lives);

whether a mother is single or married and – for married mothers – whether her husband (or “owner”) is resident in the household or elsewhere;

whether husbands and in-laws (married women) or brothers and parents (single women) are supportive of women’s efforts to handle key concerns such as financial worries, meeting the needs of children and dealing with interpersonal conflicts.

Table 2.

Mothers’ perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of life in rural and (low-income) urban areas

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Rural life |

|

|

| Urban life |

|

|

The above household forms are a response to, and have important implications for, intra-household relationships and divisions of labour and power. As discussed further below, these issues feature strongly in women’s migration and circulation patterns.

IV. COMPARING THE RURAL AND URBAN SAMPLES OF MOTHERS

THE RURAL SAMPLE of mothers was older than the general rural population of mothers with children under the age of ten (mean 32.04±7.56 vs 29.22±6.96, t=6.224, p<0.001). The urban sample did not differ significantly from the total urban GCK maternal population in age (n=370), whether or not they were lifelong urban residents, or – amongst migrants – in whether they were direct or indirect rural-urban migrants.

The rural and urban samples of mothers differed from each other in many of their characteristics (see Table 3). Rural mothers were generally older, were primarily responsible for more children under the age of ten, were more likely to be married and to follow traditional beliefs than urban mothers and were less likely to have received any formal education. Rural mothers were also more likely to live in extended households and to have husbands resident elsewhere, primarily (80 per cent) in town. While rural women were more often involved in women’s groups, urban mothers were more likely to be contributing to a merry-go-round.(17) Rural and urban mothers did not differ significantly in the likelihood that they were earning some form of income. The majority of those earning money were involved in small-scale, informal businesses in and around their communities.

Table 3.

Characteristics of lifelong rural and urban resident sample of mothers

| Mothers’ characteristics | Rural % (N=248) |

Urban % (N=284) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <35 years | 64 | 81 | <0.0001 |

| >=35 years | 36 | 19 | ||

| Marital status | Unmarried | 13 | 20 | <0.05 |

| Married | 87 | 80 | ||

| Religion | None/traditional | 70 | 32 | <0.0001 |

| Christian/Muslim | 30 | 68 | ||

| Formal education | None | 74 | 44 | <0.0001 |

| >= standard 1 | 26 | 56 | ||

| Earns any cash | None | 44 | 40 | =0.455 |

| Yes | 56 | 60 | ||

| Children < 10 | Means (SD) | 1.2 | 1.0 | <0.0001 |

| MGR* membership | Yes | 12 | 23 | <0.01 |

| No | 88 | 77 | ||

| WG** membership | Yes | 14 | 5 | <0.001 |

| No | 86 | 95 | ||

| HH type | Nuclear | 20 | 67 | <0.0001 |

| Extended | 80 | 32 | ||

| Husband’s residence | Household | 68 | 93 | <0.0001 |

| Elsewhere | 32 | 7 |

MGR = merry-go-round

WG = women’s group; (see reference 17)

V. MATERNAL MIGRATION AND ADAPTATION PATTERNS

a. Lifelong rural resident mothers

THE MAJORITY OF rural mothers were born within the rural study area (69 per cent), had lived in two or three houses since birth (80 per cent) and had been in their current household of residence for at least ten years (59 per cent). Most (81 per cent) had moved into their current households on (re)marriage. Although approximately one-third had husbands living in an urban area at the time of interview, and others had done so previously, by definition none of these mothers had lived in an urban area. Discussions suggested that one reason mothers had not moved was based on a balancing of the perceived advantages and disadvantages of rural and urban life (see Table 2). This balance was often based less on “choice” than on age and gender roles and relations, on coping in an unstable economic climate, or on the socioeconomic constraints imposed by others. Comments such as the following were frequently made:

“How can you expect a mum to live in town with the husband while her kids are [schooling] in the rural area? Husbands should at least make sure the mum comes back to be with and keep a close eye on the kids and at the same time ensure the shamba [farm] is full of crops. The husband will be free to struggle for them and will always send something back for them to spend. In case he misses contributing, they can support themselves from what the shamba has.”

“Men claim that women are supposed to be at home and visited by their husbands on month end to have their problems solved.”

“The husband may want the wife to come to town but his parents refuse. If the wife says she is going to her husband, her in-laws will complain: ‘You’re always going to your husband. Who’s going to do the duties here?’…Some men have no permission at all to take their wives to town… If he really wants you will go but some parents won’t be impressed’ This can bring witchcraft.”

b. Urban resident mothers

Most (87 per cent) urban mothers were born in a rural area, had lived in three or four households since birth (89 per cent) and had moved directly to Mombasa from a rural area (87 per cent of all those born in a rural area). Just under half of the sample had lived in Mombasa for less than two years and 30 per cent for between two and five years. The majority had initially in-migrated to stay with relatives (83 per cent), primarily husbands (65 per cent).

Discussions revealed that, upon marriage, many Mijikenda wives spend some time in their husband’s parents’ (usually rural) homestead. Incentives to later join a husband in town include the perceived advantages of living together in an urban area, the socioeconomic constraints of remaining in the rural area (see Table 2) and a husband’s request, expectation or demand. Excerpts from two case studies illustrate the range in mothers’ explanations of why they moved to join their husbands:

“I was married when I was still a young girl into my husband’s homestead…But I really had problems: my husband was in town, was not coming home and I had a child. I had no money…. When I met him I complained and he told me to join him in town. He said we’ll go home [to the rural area] when we feel like it…Yes, rural jobs are there but they are very hard [laughter].”

“I was married and taken to my husband’s [rural] home. My husband lived here in town. But I got pregnant twice and miscarried…later my child who was crawling died without any illness…So my husband knew something was wrong in his home, someone was bewitching me. We came back to town again looking for treatment from both sides [traditional and modern]. He’s now kept me here with my sorrows so I can relax. I’m not here because I’m happy but because I’m sad. I cannot go back because I know I and my children will be sick.”

Sixteen per cent of mothers who initially stayed with relatives moved with their parents and 19 per cent stayed with relatives other than husbands or parents. The latter group and “autonomous”(18) in-migrants generally fell into one of the following groups: educated young women in-migrating in search of employment; unmarried young women with little formal education, typically working at first and staying on after pregnancy/marriage; or widowed/divorced/separated women or single mothers moving to cities in search of a better life for themselves and their children. In many cases, these women reported escaping social and economic hardships in rural areas:

Kafedha: “I came from [rural] Kilifi and went to live with my husband on marriage. But we had misunderstandings so we separated and I went home to my parents. I worked for a year as a labourer on others’ farms but the work was really tough… My elder sister was already working in Ziwa la N’gombe selling mnazi [palm wine]. She came and told me if the [rural] work is too tough I should go and try town jobs…I decided to move myself to look for another life…”

Agnes: “It’s a must people at home [rural] cooperate otherwise where’s the happiness? When you get up at dawn and the others won’t greet you, or you hear ‘Oh…so and so said this and that’ you’ll feel constantly miserable. You’ll get involved in arguments. And the man I counted on as my husband didn’t even bother to come home, so I had to face all those problems alone. When I saw him I’d try to convince him of the problems but he would just tell me to tolerate: ‘…if you can’t then you decide what you’ll do about it’….my solution was to move away because life was hard…”

Regardless of form of in-migration, most mothers were familiar with the urban environment before moving and were supported socially, economically and with some form of housing as they found their feet. Kafedha’s and Agnes’s descriptions of how they settled into their new lives illustrate the importance of Mijikenda family and friends in autonomous rural-urban migration and adaptation:

Kafedha: “I first stayed with my elder sister who showed me how much mnazi you need to make a profit; how to serve customers. When I’d learnt it all, I decided to look for a place of my own: we’d lived together for two years and that can lead to misunderstandings. I found a room to rent and depended on myself. I started the business and it’s really helped me with my kids. The oldest ones live with my parents [in rural Kilifi]. I go and see them every two or three weeks, give them money and check they’re OK…I really miss them but at least they’re in school and the teachers there are considerate and easy to talk to.”

Agnes: “I first stayed with my father. I cooked sesame biscuits and sold them to a shop… I also got some work with Somali refugees: you’d help in their houses and they’d give you a little money or some flour you could later sell…But then even my own father decided to chase me away… I imagined having two children yet being unsettled: I had to pay rent on the room and couldn’t be sure we’d have enough for food and clothes. I decided to start a business in mnazi. Eventually, it started going well and even expanding. In the end, I earned enough to satisfy me and my children. All work has problems but I stuck at it until I could build my own house and later another one with four rooms for rent. So now I can say I am thankful because it was bad, and good moving from the rural area to here. The only problem with this place compared to rural is that everything you put in your mouth you have to pay for.”

Although urban women are able to escape some of the rural hardships, particularly those associated with heavy domestic work, strained relations with members of extended households, and missing an absent husband, rural and urban mothers also share many concerns (see Table 2). Urban mothers can also be subject to new or different hardships and controls. Some married or cohabiting mothers complain they are more strictly supervised by their husbands, for example, and a number of single or divorced women claimed they were tolerating loveless “economic relationships” to ensure the rent is paid and the children are fed.

VI. MATERNAL MOBILITY AND RURAL-URBAN TIES

a. Amount of mobility

A LARGE PROPORTION of rural and urban mothers had been on at least one overnight trip in the year preceding the interviews/since in-migration to the current household; 17 per cent and 33 per cent respectively had slept elsewhere for a total of at least 10 per cent of nights. Most circular mobility was irregular (less than once every three months), most commonly to attend a funeral, visit relatives, seek/administer health care,(19) and carry out farm work (see Table 4). Rural mothers’ regular trips (made at least once every three months) were largely to visit absent husbands (55 per cent). Urban mothers’ regular trips were principally to visit a partner’s family (31 per cent), to visit their own parents (15 per cent) and to work on a farm (15 per cent). Rural mothers’ circulation was primarily rural-rural movement, while urban mothers’ circulation was largely urban-rural (76 per cent).

Table 4.

Mothers’ reported reasons for irregular trips over the last year

| Reasons | Lifelong rural | Urban | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

|

| ||||

| Funeral/burial | 184 | (40) | 133 | (26) |

| Visiting relatives | 114 | (25) | 178 | (34) |

| Sickness-related | 63 | (14) | 58 | (11) |

| Farm work | 56 | (12) | 42 | (8) |

| Celebrations | 21 | (5) | 47 | (9) |

| Other | 25 | (5) | 60 | (12) |

| Total | 463 | (100) | 518 | (100) |

In most of their irregular trips (68 per cent), rural mothers were not accompanied by all of their children under the age of ten. Children left in the homestead were cared for by their grandmother (31 per cent), other women in the household (21 per cent) or other children (21 per cent). Urban mothers were more commonly accompanied by all of their children under the age of ten (74 per cent). Where children were left in the house, they were left in the care of their father (42 per cent), other children (20 per cent) or a neighbour/friend (20 per cent). Breast-fed children are almost always taken on overnight trips by both rural and urban mothers.

Rural and urban mothers’ circulatory mobility patterns are related to the importance of the extended family; with its web of rights and duties, the extended family serves as a day-care, social security and welfare system. A key factor in maintaining this supportive (and sometimes draining) net is physical interaction, in which goods, money, ideas, news and social support are exchanged. Funerals in particular are an important forum to reunite not only with the broader extended family but also with members of the wider community. Funeral attendance confirms one’s state of “belonging” to the homestead and community.

b. Selectivity in mobility

To identify the most mobile rural and urban mothers, mothers were grouped in two ways and their demographic and socioeconomic characteristics compared:

by amount of circulation: “mobile mothers” are defined as those who had spent a total of 10 per cent or more nights away in the year preceding the interviews/since migration into the household of current residence (rural mothers n=43 (17 per cent); urban mothers n=85 (33 per cent)); “non- or less mobile” mothers are defined as those who had spent less than 10 per cent nights away (rural mothers n=205 (83 per cent); urban mothers n=189 (67 per cent));

by destination of circulation: rural mothers were grouped according to whether they had a total of less than 1 per cent, or 1 per cent or more, nights in an urban area (n=200 (80 per cent) and n=48 (20 per cent), respectively). Urban mothers were grouped according to whether they had spent a total of less than 10 per cent, or 10 per cent or more, nights in a rural area (n=199 (67 per cent) and n=95 (33 per cent), respectively).

The only significant differential in rural mothers’ mobility was place of residence of husband. Mothers with absent husbands were more likely to have spent 10 per cent or more nights away (X2 6.50, p<0.01) and 1 per cent or more nights in an urban area (X2 15.68, p<0001). In addition to the more routine visits to collect remittances and to relax after cultivation/harvesting, wives reported visiting their husbands for financial and social support in times of hardship, or because they had been summoned.

A number of variables were univariately associated with urban mothers’ mobility patterns, including age, formal education, whether or not mothers were earning an income, sex of household head and length of residence in town. After adjusting for other variables using logistic regression, significant associations were maintained only for educational status and income. Mothers were more likely to have travelled for 10 per cent or more nights and to have spent 10 per cent or more nights in a rural area if they had at least four years of formal education (p<0.01 and p<0.001 respectively) and if they were earning an income (p<0.05). One explanation might be that these mothers have relatively good bargaining power within households (including for travel). However, intra-household power relations are highly complex(20) and we did not explore whether mothers actually wished to travel. It is of interest that length of urban residence remained significant in predicting urban mothers’ mobility to rural areas (p<0.05) only when marital status and income were excluded from the analyses.

c. Rural-urban ties

In addition to mothers’ mobility patterns, strong rural-urban ties are illustrated in a number of ways.

First, percentage nights of contact (includes mothers’ own circulation and visitors received by the household) between rural and urban residents over the last year or since in-migration: 10 per cent of lifelong rural resident mothers had spent at least 20 per cent of nights with urban residents; and 14 per cent urban of residents had spent at least 20 per cent of nights with rural residents. Second, regular assistance of individuals other than nuclear family members resident in the household: 61 per cent of urban mothers reported assisting at least one individual resident elsewhere. Those assisted were generally resident in one household (90 per cent), the majority of which were in a rural area (90 per cent). Finally, hopes for retirement: the majority of rural and urban mothers stated that they wished to “retire” in a rural area (95 per cent and 74 per cent respectively). Amongst urban resident mothers, this was more likely amongst migrants than amongst lifelong urban residents (76 per cent and 42 per cent, respectively).

VII. DISCUSSION

IN DESCRIBING MOBILITY patterns, rural-urban linkages and household structures, this paper draws heavily on survey work and interviews with mothers of children under the age of ten. Including a broader cross-section of participants would have afforded a more balanced overview of the dynamics explored. A more detailed examination of mother-child dynamics would also have offered greater insights into the way in which children feature in these socio-demographic processes. Nevertheless, the practical difficulties of carrying out a census in a low-income urban area are enormous.(21) There are therefore few detailed local-level comparisons of rural and urban age-sex structures. Our study design enabled us to present a case study and to contribute to a small but growing pool of empirical data on female mobility patterns. In this section, we summarize and discuss the findings on population and household structures and on mobility and intra-household relations. We conclude with brief comments on the implications for planners and policy makers.

a. Rural and urban population and household structures

Dramatic differences were observed in the rural and urban age-sex and household structures (see Figures 2 and 3, and Table 1), and in the samples’ characteristics (see Table 3). These differences are due largely to the division of extended and nuclear households across rural and urban areas; a survival strategy aimed at balancing the income-earning opportunities in town; the relatively low cost of living in rural areas; and future familial security. Changes in fertility patterns following rural-urban migration, or amongst lifelong urban residents, may also play a role but it was not possible to investigate this in the current study.

Mothers’ perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of rural and urban life (see Table 2) illustrate that the benefits that accrue from survival strategies that span the rural-urban divide do not come without practical and emotional costs, including those associated with living apart from partners and children. As Geschiere and Gugler(22) point out, it is striking that the emotional stresses of living with or apart from various family members have received so little research attention.

The ways in which households are split across rural and urban areas are clearly influenced not only by the contrasting economies of the two areas but also by intra-household relations based largely on age, sex and relationship to household head. These factors shape the extent and nature of all household members’ involvement in rural-urban migration streams over their lifetimes. This is illustrated by tentative suggestions of what causes some of the more specific differences in the study areas’ population structures (see Table 5), these suggestions being based largely on mothers’ explanations for and against rural-urban migration. The latter demonstrate that there is often a high degree of agency in female rural-urban migration on the Kenyan coast, but also that mothers’ determination to meet the needs of their children in what is often a harsh socioeconomic environment is a key factor in mobility decisions. It is of interest that many children, particularly boys, are left in the rural area while mothers move to town (see Figures 2 and 3). One reason is to allow children to attend relatively cheap rural schools. Gross enrolment rates are 50 per cent for girls and 65 per cent for boys at primary level and 10 per cent and 45 per cent, respectively, at secondary level, with higher drop-out rates at both levels among girls.(23) Other reasons include the relatively cheap cost of living in rural areas, greater discipline and protection in rural areas from urban physical and moral hazards, and mothers’ access to trusted family members. Although mothers may be more worried about leaving female children in rural homes, this was not mentioned by them, nor explored.

Table 5.

Explanations for differences in the rural and urban population structures

| Differences in population structures |

Suggested explanations (based on this study) for the difference |

|---|---|

|

The relatively low

proportion of girls and particularly boys aged 5-15 in the urban population* |

|

|

The relatively high

male:female ratio for those aged 20-35 in the urban population |

|

|

The relatively high

proportion of women aged 20-30 in the urban population |

|

Changes in fertility patterns following rural-urban migration and/or amongst lifelong urban residents may also play a role but it is beyond the scope of this study to explore this issue.

The study area population pyramid shapes are typical for rural-urban population comparisons in sub-Saharan Africa, including those of Kenya. Nevertheless, when overlaid on those produced using the most recent rural and urban census data(24) a number of differences are revealed, including:

the proportion of under-15-year-olds is significantly lower (X2 615.27; p<0.00001) in the urban study population (26 per cent) than in the national urban population (36 per cent);

the proportion of 20 to 35-year-olds is significantly higher (X2 1178.97; p< 0.00001) in the urban study population (50 per cent) than in the national urban population (36 per cent);

male:female ratios in the urban study population are far greater than the national urban ratios (163:100 and 120:100, respectively).

These differences are likely to result from the high proportion of in-migrants in the urban study area and to be true of many low-income urban settings elsewhere in Kenya. They suggest it would be problematic for planners working in similar low-income urban communities to base estimates of population structure and numbers simply on national or city-wide data, particularly when targeting specific groups within communities. Preliminary surveys should enable more accurate estimates of population structure and expected numbers of participants, and should highlight some of the operational difficulties that might need to be considered.

b. Mobility and intra-household relations

Both inter- and intra-household relations, and in particular households “split” across rural and urban areas, ensure that much rural-urban migration and adaptation to the urban environment takes place within Mijikenda networks. The majority of rural-urban migrants are therefore familiar with the urban environment before moving, and many maintain strong rural-urban ties after moving. A large literature suggests that these patterns are typical of many sub-Saharan African settings, even where the rural and urban populations lie far farther apart.(25) Our study therefore supports the assertion made by numerous others that to stereotype rural-urban migrants as isolated and alienated may be highly misleading, and highlights that this is also the case for female migrants.

It may be that simple survey definitions of household (selected for practical reasons) are an important factor in creating stereotypes of isolated migrants and in over-estimates of the pace of extended family breakdowns associated with urbanization. In our study for example, 86 per cent (n=133) of a randomly selected sub-sample of urban households claimed to be linked (shared meals at least once a month, or assisted financially in times of need) to at least one other household in town. Most linked households were family members. Conversely, households defined as extended in rural areas will have a wide range of socioeconomic compositions, including many that function largely as clusters of nuclear families and many that are headed by a single, often female, parent.(26)

The complex physical and socioeconomic organization of households makes it difficult to generalize about the situation of women, even amongst a relatively small group of mothers of a specific ethnicity. This is further complicated by the centrality of the specific nature of conjugal and other relationships in women’s experiences, concerns and opportunities (see Table 2). Such diversity supports others who question a number of the dualities evident in the gender and migration literature, including the division between “autonomous” and “associative” female migration, “rural” vs. “urban” residence and female- vs. male-headed households.(27) These dualities are useful in basic descriptions of patterns of migration but great caution should be exercised in using these data to explain mobility patterns or to target developmental efforts.

Intricate rural-urban inter-relationships will inevitably lead to a continuous exchange of “rural” and “urban” information, goods, ideas and practices. This was an important factor in the rural and urban samples’ similarity in responses to child illnesses for example, despite relatively good physical access to formal and informal biomedical services in the urban study area:(28) over the year preceding the interviews, just over half of all rural and urban mothers had used bio cultural (or “traditional”) therapy to treat a child, and approximately one-fifth of rural and urban mothers’ actions in response to childhood convulsions involved consulting a healer (22 per cent (n= 9) and 19 per cent (n=24), respectively); over the two weeks preceding the interviews, 69 per cent of rural and urban mothers used shop-bought medicines first, or only, to treat uncomplicated childhood fevers.

c. Planning and policy recommendations

Policies and programmes aimed at alleviating hardships faced in rural and urban communities should be cautious about employing rigid and homogeneous understandings of household arrangements and social relations and should give careful consideration to complex linkages within and across rural and urban settings. Failure to do this risks obscuring the underlying causes of poverty, mistargeting resources and even damaging established social and economic support networks. Building upon precarious but beneficial equilibria requires an understanding of complex relations within and between multi-spatial households and of the way in which these influence the daily lives and carefully established priorities of men and women. Drawing upon participatory approaches and conceptualizations of the household as spaces in which relations between individuals are based on bargaining and negotiation can be a constructive basis for such an understanding.(29)

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Wellcome Trust, UK (grant number 033340) and the Kenyan Medical Research Institute. We wish to thank Dr Norbert Peshu and Professor Kevin Marsh for their support and comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to the fieldworkers, data-entry clerks and administrative staff at the KEMRI Unit for their hard work, and particularly to the rural and urban study area residents whose assistance and cooperation made the study possible. R W Snow is supported by the Wellcome Trust as part of their senior fellowship programme in basic biomedical sciences. This paper is published with the permission of the director of KEMRI.

Contributor Information

C S Molyneux, Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Centre for Geographic Medicine Research, P O Box 230, Kilifi, Kenya.

V Mung’ala-Odera, Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Centre for Geographic Medicine Research, P O Box 230, Kilifi, Kenya.

T Harpham, Department of Urban Policy and Planning, South Bank University, Wandsworth Road, London SW8 2JZ, UK.

R W Snow, Kenya Medical Research Institute/Wellcome Trust Collaborative Programme, P O Box 43640, Nairobi, Kenya..

References

- 1.Brokerhoff M, Brennan E. The poverty of cities in developing regions. Population Development Review. 1998;(24):75–114. [Google Scholar]; Mitlin D, Satterthwaite D, Stephens C. City inequality. Environment & Urbanization. 1996;8(2):3–7. [Google Scholar]; Potts D. Shall we go home? Increasing urban poverty in African cities and migration processes. The Geographic Journal. 1995;(161):245–264. [Google Scholar]; and ; Todd A. Health inequalities in urban areas: a guide to the literature. Environment & Urbanization. 1996;8(2):141–152. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gould WTS. African mortality and the new ‘urban penalty’. Health & Place. 1998;(4):171–181. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(98)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harpham T. Urbanisation and health in transition. Lancet. 1997;(349):11–13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanner M, Harpham T. Action and research in urban health development – progress and prospects. In: Harpham T, Tanner M, editors. Urban Health in Developing Countries: Progress and Prospects. Earthscan; London: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tacoli C. Beyond the rural-urban divide. Environment & Urbanization. 1998;10(1):3–4. [Google Scholar]; also; Brokerhoff M, Eu H. Demographic and socioeconomic determinants of female rural-urban migration in sub-Saharan Africa. International Migration Review. 1993;(27):557–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; and; Wright C. Gender awareness in migration theory: synthesising actor and structure in southern Africa. Development and Change. 1995;(26):771–791. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parkin D. Along the line of the road: expanding rural centres in Kenya’s Coast province. Africa. 1979;(49):273–282. [Google Scholar]; ; also ; Parkin D. Sacred Void: Spatial Images of Work and Ritual among the Giriama of Kenya. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Government of Kenya . Analytical Report (VI): Migration and Urbanization. Central Bureau of Statistics; Nairobi: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.See references 6 and 7.

- 9.See reference 6; also ; Snow RW, Mung’ala VO, Foster D, Marsh K. The role of the district hospital in child survival at the Kenyan coast. African Journal of Health Sciences. 1994;(1):71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Government of Kenya . Mombasa District Development Plan 1994-96. Office of the Vice-President/Ministry of National Planning and Development; Nairobi: 1994. [Google Scholar]; The poverty line was based on household expenditure necessary to afford a minimum nutritionally adequate diet and essential non-food expenditure items, adjusted for household size and age structure. As Rakodi et al. note (see reference 11), this income poverty line is considered reasonably reliable because Kenya has received considerable assistance in developing and analyzing measures from the World Bank.

- 11.Rakodi C, Gatabaki-Kamau R, Devas N. Poverty and political conflict in Mombasa. Environment & Urbanization. 2000;12(1):153–170. [Google Scholar]

- 12.See references 10 and 11; also ; Kindy H. Life and Politics in Mombasa. East African Publishing House; Nairobi: 1972. [Google Scholar]; Mazrui AA. Mombasa: Three stages towards globalization. In: King AD, editor. Representing the City: Ethnicity, Capital and Culture in the Twenty-first Century Metropolis. New York University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]; and; Nyingi P, Kinyua K. Decentralized cooperation and joint action: Mombasa case study. no date. www.oneworld.org/ecdpm/pubs.

- 13.A household was defined as “a person or group of people living in the same house, who are answerable to the same head and share a common source of food and/or income”. A resident was defined as someone with a sleeping place within a household who had already or intended to remain there for a total of at least six months. This six-month “cut-off” was based on extensive pilot work in both study areas.

- 14.This selection decision was based on the broader study aim to compare rural and urban mothers’ treatment-seeking behaviour and, in particular, to look at changes in responses to child illnesses following rural-urban migration. One third of rural resident mothers were excluded from the detailed survey work because they had already “lived” (see reference 13) in an urban area. This selection is likely to have influenced the rural sample’s characteristics, their mobility patterns and their rural-urban ties but the directions are difficult to predict.

- 15.The six-month “cut-off” was maintained to distinguish between “circulation” (non-permanent moves, excluding daily movements) and “definitive migration” (a permanent change in residence). Details on place, reason and duration of each residency (since birth) or overnight trip (over the previous 12 months) were recorded.

- 16.Molyneux CS, Mung’ala-Odera V, Harpham T, Snow RW. Intra-household relations and treatment decision-making for child illness: a Kenyan case study. Journal of Biosocial Sciences. 2002;(34):109–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.In merry-go-rounds, a number of people, usually friends, contribute an agreed sum of money to the group on a regular basis, with each member having a turn at receiving the sum of the others’ contributions. Women’s groups were initially established by the government, with financial contributions used to develop a communal business, the profits from which are divided between members. For more information on savings schemes, see; Munwanga EHA. Use and impact of savings services for poor people in Kenya. 1999 http://www/undp.org.sum.

- 18.Change in residence was defined as autonomous only when in response to divorce from, or death of, a husband or for the specific purpose of employment/ business.

- 19.Includes staying in or near a hospital or healer in order to receive treatment or to care for someone receiving treatment, and travelling to assist someone who has recently given birth.

- 20.See reference 16.

- 21.Parry C. Quantitative measurement of mental health problems in urban areas: opportunities and constraints. In: Harpham T, Blue I, editors. Urbanization and Mental Health in Developing Countries. Avebury, Aldershot: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geschiere PJ, Gugler AS. The urban-rural connection: changing issues of belonging and identification. Africa. 1998;(68):309–319. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kilonzo N. A gender perspective of entrepreneurial activities, patterns of access, control and ownership of resources in Kilifi district. 2001 unpublished document .; These patterns contribute to Kilifi district ranking 36th out of 45 districts in Kenya in terms of inequality between women and men, as measured by the UNDP Gender Development Index (based on statistical differences between men and women in life expectancy, educational attainment and real income).

- 24.See reference 7.

- 25.See reference 5.

- 26.See reference 16.

- 27.See, for example, ; Akin Aina T, Baker J, editors. The Migration Experience in Africa. Gotab; Sweden: 1995. [Google Scholar]; also ; Bradshaw S. Female-headed households in Honduras: perspectives on rural-urban differences. Third World Planning Review. 1995;(17):117–31. [Google Scholar]; Appleton S. Women-headed households and household welfare: an empirical deconstruction for Uganda. World Development. 1996;(24):1811–1827. [Google Scholar]; Chant S. Women-headed households: poorest of the poor? Perspectives from Mexico, Costa Rica and the Philippines. IDS Bulletin. 1997;(28):26–48. [Google Scholar]; Chant S. Households, gender and rural-urban migration: reflections on linkages and considerations for policy. Environment & Urbanization. 1998;10(1):5–22. doi: 10.1177/095624789801000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sen A. Gender and cooperative conflicts. In: Tinker I, editor. Persistent Inequalities: Women and World Development. Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]; and ; Bryceson DF, editor. Women Wielding the Hoe: Lessons from Rural Africa for Feminist Theory and Development Practice. Berg Publishers; Oxford: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.See reference 16; also ; Molyneux CS, Mung’ala-Odera V, Harpham T, Snow RW. Maternal responses to childhood fevers: a comparison of rural and urban residents in coastal Kenya. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 1999;(4):836–845. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.See references 11 and 27;; IIED . RRA Notes 21: special issue on participatory tools and methods in urban areas. London: 1994. [Google Scholar]; Keough N. Participatory development principals and practice: reflections of a Western development worker. Community Development Journal. 1998;(33):187–196. [Google Scholar]; Sustainable cities revisited III. Environment & Urbanization. 2000;12(2):3–8. “Editorial. [Google Scholar]; Cornwall A, Musyoki S, Garett P. In search of a new impetus: practitioners’ reflections on PRA and participation in Kenya. Institute of Development Studies; Brighton, Sussex: 2001. IDS Working Paper 131. [Google Scholar]; Environment & Urbanization Brief No 1, “Towards more pro-poor local governments in urban areas”, Brief of April 2000 issue on “Poverty reduction and urban governance”.