Abstract

Objectives

Radical cystectomy (RC) is the standard treatment for muscle-invasive Urothelial carcinoma of the bladder (UCB). Tri-modality bladder preserving therapy (BPT) is an alternative to RC, but randomized comparisons of RC versus BPT have proven infeasible. To compare RC versus BPT, we undertook an observational cohort study using registry and administrative claims data from the SEER-Medicare database.

Methods

We identified patients age 65 years or older diagnosed between 1995 and 2005 who received RC (n=1,426) or BPT (n=417). We examined confounding and stage misclassification in the comparison of RC and BPT using multivariable adjustment, propensity score-based adjustment, instrumental variable (IV) analysis and simulations.

Results

Patients who received BPT were older and more likely to have comorbid disease. After propensity score adjustment, BPT was associated with an increased hazard of death from any cause (HR 1.26; 95% CI, 1.05 – 1.53) and from bladder cancer (HR 1.31; 95% CI, 0.97 – 1.77). Using the local area cystectomy rate as an instrument, IV analysis demonstrated no differences in survival between BPT and RC (death from any cause HR 1.06; 95% CI, 0.78 – 1.31; death from bladder cancer HR 0.94; 95% CI, 0.55 – 1.18). Simulation studies for stage misclassification yielded results consistent with the IV analysis.

Conclusions

Survival estimates in an observational cohort of patients who underwent RC versus BPT differ by analytic method. Multivariable and propensity score adjustment revealed greater mortality associated with BPT relative to RC, while IV analysis and simulation studies suggest that the two treatments are associated with similar survival outcomes.

Keywords: Comparative Effectiveness Research, Urinary bladder neoplasms, Cystectomy, Radiotherapy, Chemotherapy, SEER Program

INTRODUCTION

Urothelial carcinoma of the bladder (UCB) affects over 70,000 people annually in the United States, the majority of who are elderly, and accounts for nearly 5% of the total cost of cancer care to Medicare. A substantial portion of patients present with or progress to muscle-invasive UCB, an aggressive cancer associated with a high risk of death from metastatic disease.

Radical cystectomy (RC) is the guideline-recommended standard treatment for muscle-invasive UCB and involves removal of the bladder and prostate for men and anterior exenteration (including the bladder, uterus, ovaries, and part of the vagina) for women. Bladder preserving therapy (BPT), a curative treatment regimen comprised of transurethral resection (TUR) of the bladder tumor, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, presents a compelling alternative to RC because long term studies have shown that the majority of BPT patients retain good bladder function [1,2]. Yet, concerns about reduced survival without radical surgery remain and randomized comparisons of RC to BPT have proven infeasible.

Non-randomized studies of RC versus BPT suffer from two sources of bias that threaten validity in observational cancer comparative effectiveness research (CER): confounding and misclassification. Confounding occurs when measured or unmeasured differences between patients are related to both the exposure (e.g. treatment assignment) and outcome in a way that creates a false association; for example, patients receiving cystectomy tend to be younger, have fewer comorbidities and better performance status. Cancer registry datasets, often employed for observational cancer CER, capture variables for patient age and comorbidities, but do not report performance status, an important unmeasured confounder.

Adjustment for measured confounding depends on the ability to accurately observe possible confounding variables. Cancer registry datasets may mischaracterize important confounding variables; controlling for such variables may exacerbate rather than reduce bias. For patients with UCB, those who undergo RC have pathologic staging while those who undergo BPT have clinical staging. Clinical stage is based on available information obtained prior to cystectomy, including bi-manual physical examination, imaging, and cystoscopy. Pathologic staging adds additional information obtained from microscopic examination of the bladder specimen after cystectomy. Discordance between clinical and pathological stage induces bias in the comparison of RC to BPT because clinical staging is more likely to underestimate muscle invasion, a pathologic finding which is associated with worse survival outcomes [3].

We conducted this study to evaluate differences in survival in the comparison of RC to BPT using traditional multivariable regression and propensity score adjustment, which adjust for measured confounding, and instrumental variable analyses, which theoretically accounts for both measured and unmeasured confounding. Our secondary aim was to examine the sensitivity of traditional regression survival estimates to stage misclassification through simulation.

METHODS

Study Design

The study was a retrospective, observational cohort study using registry and administrative claims data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database. This research was approved by the institutional review board.

Data Sources

The SEER-Medicare database links patient demographic and tumor-specific data collected by SEER cancer registries to Medicare claims for inpatient and outpatient care. To obtain information on physicians and hospitals, Medicare claims were merged with the Medicare Physician Identification and Eligibility Record (MPIERS) and the SEER-Medicare hospital file. To explore candidate instruments, we grouped patients into hospital referral regions (HRRs) defined by the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. HRRs represent regional health care markets for tertiary medical care.

Study Population

We identified 54,402 patients with UCB age 65 years or older diagnosed between January 1, 1995 and December 31, 2005 in SEER with follow up through December 31, 2008 in Medicare. To assign patients to therapy during the 6 month period after diagnosis, we excluded 12,801 patients enrolled in a health maintenance organization and 2890 patients not enrolled in the fee-for-service Part B Medicare program (health care claims may not be submitted for such patients). We identified 6,486 patients with muscle-invasive (stage 2 and 3) UCB after excluding patients who were not staged (n = 2,866), stage 0 (19,206), stage 1 (8,796), and stage 4 (1,357).

To define the primary analytic cohort eligible for either RC or BPT, we made the following additional exclusions: RC with chemotherapy or radiotherapy (401), radiotherapy with non-platinum based chemotherapy (166), palliative treatment with chemotherapy alone, radiotherapy alone, or expectant management (combined 3,843), non-concurrent chemoradiotherapy (e.g. administered > 3 months apart, 54), absent Medicare codes for initial TUR (64), HRRs with ≤ 10 patients over the study period (50) and unknown race [2]. To avoid survivorship bias, we excluded patients who died within three months of diagnosis (n=71; RC is associated with peri-operative mortality while BPT required that patients “survive” to receive tri-modality therapy). The primary analytic cohort was comprised of 1,426 RC and 417 BPT patients.

Definition of Variables

RC and BPT were assigned based on identification from Medicare inpatient, outpatient, and physician/supplier component files using ICD-9 and CPT/HCPCS [4-6]. RC was defined as complete cystectomy with or without pelvic lymph node dissection or pelvic exenteration. BPT was defined as consisting of TUR of the bladder tumor, concurrent platinum-based chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Patient characteristics included age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, tumor grade, and comorbid disease. Comorbidities were identified by classifying all available inpatient and outpatient Medicare claims for the 12-month interval preceding UCB diagnosis into 46 categories [7]. We staged patients’ cancer according to American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual, 6th edition using SEER variables for disease extent. SEER registries collect pathologic staging for RC patients and clinical staging for non-surgical patients. Physician and hospital characteristics served as proxies for volume, experience, and practice style. Physician characteristics included years in practice (from medical school graduation) and hospital characteristics included number of beds and academic affiliation. Patients were assigned to urologists and hospitals on the basis of identifiers associated with TUR billing claims. Contextual variables included year of diagnosis, registry, population of county of residence, and median household income in census tract of residence (US$, obtained from the Patient Entitlement and Diagnosis Summary File provided with SEER-Medicare data).

The primary outcomes were time to death from any cause and time to death from bladder cancer. Underlying cause of death was determined from SEER records. The observation time for follow-up was calculated as the time from either cystectomy or the start date of radio- or chemotherapy until the Medicare date of death or end of follow-up (December 31, 2008). In the analysis of death from bladder cancer, patients who died from a cause other than bladder cancer were also censored at the Medicare date of death.

Statistical Analysis

We assessed covariate imbalances between treatment groups using chi-square statistics and t-tests. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to compare estimates of unadjusted overall survival (OS) and bladder cancer specific survival (BCSS). For multivariable adjustment, patient, demographic, and physician/hospital variables were included in the multivariable model, except for tumor stage [8]. We excluded stage from our primary analyses of confounding in multivariable, propensity score, and instrumental variable models and addressed the influence of stage misclassification on survival through simulation studies.

For propensity score adjustment, we calculated propensity scores using multivariable logistic regression with receipt of RC as the outcome of interest, adjusting for patient, demographic, and physician/hospital characteristics. We used Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests to determine whether covariates were balanced within propensity score quintiles and found that all covariates were balanced (Table 1). In propensity score models, we adjusted for propensity score as a continuous variable [10]. In secondary propensity score-based models, we used inverse probability-weighted estimation [11].

Table 1.

Distribution of Characteristics across Treatment Groups before and after Propensity Score Adjustment

|

P Value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radical Cystecomy | Bladder Preserving Therapy | Before adjustment | After propensity adjustment | |||

| Number | (%) | Number | (%) | |||

| All patients | 1,426 | (77.4) | 417 | (22.6) | ||

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Age at diagnosis (mean, SD) | 75.4 | (6.2) | 79.3 | (6.0) | <0.001 | 0.21 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 892 | (62.6) | 300 | (71.9) | ||

| Female | 534 | (37.4) | 117 | (28.1) | <0.001 | 0.76 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1308 | (91.7) | 392 | (94.0) | 0.07 | 0.91 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 860 | (60.3) | 233 | (55.9) | ||

| Not married | 525 | (36.8) | 171 | (41.0) | 0.27 | 0.97 |

| Tumor Grade | ||||||

| Moderately differentiated | 92 | (6.5) | 27 | (6.5) | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 1309 | (91.8) | 376 | (90.2) | 0.16 | 0.97 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 920 | (64.5) | 285 | (68.3) | 0.15 | 0.93 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 407 | (28.5) | 117 | (28.1) | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| Arrythmia | 311 | (21.8) | 123 | (29.5) | 0.001 | 0.81 |

| Anemia | 320 | (22.4) | 95 | (22.8) | 0.88 | 0.97 |

| Perivascular disease | 265 | (18.6) | 109 | (26.1) | <0.001 | 0.70 |

| Diabetes | 277 | (19.4) | 83 | (19.9) | 0.83 | 0.96 |

| Hypothyroidism | 216 | (15.1) | 67 | (16.1) | 0.65 | 0.96 |

| Congestive heart failure | 155 | (10.9) | 76 | (18.2) | <0.001 | 0.49 |

| Valvular disease | 159 | (11.2) | 65 | (15.6) | 0.01 | 0.93 |

| Electrolyte abnormality | 132 | (9.3) | 47 | (11.3) | 0.22 | 0.94 |

| Other comorbidity | 390 | (27.3) | 132 | (31.7) | 0.09 | 0.94 |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Population of county of residence | ||||||

| 1,000,000 or more | 783 | (54.9) | 222 | (53.2) | ||

| 250,000 to 999,999 | 294 | (20.6) | 91 | (21.8) | ||

| 0 to 249,999 | 349 | (24.5) | 104 | (24.9) | 0.81 | 0.91 |

| Median household income in census tract of residence (US$) | ||||||

| 25,000 or less | 165 | (11.6) | 31 | (7.4) | ||

| > 25,000 to 40,000 | 477 | (33.5) | 121 | (29.0) | ||

| > 40,000 to 60,000 | 463 | (32.5) | 170 | (40.8) | ||

| > 60,000 | 310 | (21.7) | 91 | (21.8) | 0.008 | 0.99 |

| Hospital and physician characteristics | ||||||

| Hospital academic affiliation | 749 | (52.5) | 209 | (50.1) | 0.69 | 0.99 |

| Hospital beds | ||||||

| ≤ 148 | 356 | (25.0) | 93 | (22.3) | ||

| 149 - 238 | 344 | (24.1) | 103 | (24.7) | ||

| 239 - 342 | 329 | (23.1) | 117 | (28.1) | ||

| ≥ 343 | 357 | (25.0) | 85 | (20.4) | ||

| Unknown | 40 | (2.8) | 19 | (4.6) | 0.04 | 0.99 |

| Physician practice years | ||||||

| ≤ 16 | 337 | (23.6) | 111 | (26.6) | ||

| > 17 - 24 | 365 | (25.6) | 88 | (21.1) | ||

| > 24 - 33 | 373 | (26.2) | 113 | (27.1) | ||

| > 33 | 307 | (21.5) | 103 | (24.7) | 0.007 | 0.98 |

*Selected race, ethnicity, marital status, grade, and physician practice cells suppressed according to SEER-Medicare guidelines for reporting cell sizes < 11 patients. Ethnicity was balanced after propensity score adjustment (data not shown).

Note: During the study period, information on incident cancer cases was available from 16 cancer registries covering approximately 26% of the US population. The Greater California, Kentucky, Louisiana, and New Jersey case contributions began in 2000. The highest RC rate was in San Francisco and the highest BPT rate was in Iowa. Diagnosis year and registry covariates were balanced after propensity score adjustment (data not shown).

We constructed multivariable Cox proportional hazard models to compare death from any cause and from bladder cancer between RC and BPT, accounting for within-hospital correlation using robust variance estimates [12]. Missing or unknown values were entered into models as dummy variables of a separate category [9]. The proportion missing among the six variables with any missing data was minor (< 5%). To assess the proportional hazards assumption, we evaluated the Schoenfeld residuals test and complementary log plots, and found that the proportional hazards assumption was violated in some models [13]. Therefore, we examined the sensitivity of our results to violations of proportionality by repeating the analysis using Weibull Accelerated Failure Time (AFT) models, which do not require the assumption of proportional hazards [14].

Instrumental Variable Analysis

We formulated the IV as the local area cystectomy rate. The instrument was created by using the entire cohort of patients with Stage 1 – 4 UCB who were potentially eligible for surgical intervention (n = 16,639), after excluding geographically smaller HRRs with ≤ 10 patients (n = 306). We assigned patients to HRRs on the basis of their zip code at diagnosis, and calculated the local area cystectomy rate over the 11 year study period by dividing the number of patients who received RC by the total number of cohort patients in the HRR. Cystectomy rates did not change significantly over the study period. To limit the possibility that a patient's treatment decision would inform their assigned instrument, we excluded each patient from the calculation of their own instrument. Therefore, the instrument was defined as the proportion of all other patients (Stage 1 – 4) in an individual's HRR who received RC.

The local area cystectomy rate is a strong instrument for several reasons. First, it captures regionally distinct structural variation in care driven by factors beyond patient characteristics, including variation in urologist workforce supply, physician geographic distribution, and physician practice patterns [4]. Second, it varies across HRRs and is strongly associated with treatment assignment in the primary analytic cohort (F statistic = 34.9, where values < 10 are considered weaker instruments) [15]. Third, it balanced prognostically important observed covariates when the primary analytic cohort was split above and below the median cystectomy rate (Table 2). Balance in average patient characteristics across the IV offers reasonable evidence to infer that the IV is not systematically related to unmeasured confounding variables.

Table 2.

Distribution of Characteristics across Cohorts Grouped by Median Value of Instrument*

| Below Median IV | Above Median IV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | (%) | Number | (%) | P Value | |

| All patients | 918 | (49.8) | 925 | (50.2) | |

| Median survival (yrs, 95% CI) | 3.7 (3.1 – 4.2) | 3.4 (2.9 – 3.9) | 0.71† | ||

| Treatment | |||||

| Radical cystectomy | 675 | (73.5) | 751 | (81.2) | |

| Bladder preserving therapy | 243 | (26.5) | 174 | (18.8) | <0.001 |

| Patient characteristics* | |||||

| Age at diagnosis (mean, SD) | 76.5 | (6.4) | 76.1 | (6.4) | 0.17 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 590 | (64.3) | 602 | (65.1) | |

| Female | 328 | (35.7) | 323 | (34.9) | 0.72 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 851 | (92.7) | 849 | (91.8) | <0.001 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 548 | (50.1) | 545 | (49.9) | |

| Not married | 335 | (48.1) | 361 | (51.9) | 0.06 |

| Tumor Grade | |||||

| Moderately differentiated | 57 | (6.2) | 62 | (6.7) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 836 | (91.0) | 849 | (91.8) | 0.29 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 589 | (64.2) | 616 | (66.6) | 0.27 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 254 | (27.7) | 270 | (29.2) | 0.47 |

| Arrythmia | 224 | (24.4) | 210 | (22.7) | 0.39 |

| Anemia | 209 | (22.8) | 206 | (22.3) | 0.80 |

| Perivascular disease | 187 | (20.4) | 187 | (20.2) | 0.93 |

| Diabetes | 170 | (18.5) | 190 | (20.5) | 0.27 |

| Hypothyroidism | 130 | (14.2) | 153 | (16.5) | 0.16 |

| Congestive heart failure | 119 | (13.0) | 112 | (12.1) | 0.58 |

| Valvular disease | 124 | (13.5) | 100 | (10.8) | 0.08 |

| Electrolyte abnormality | 96 | (10.5) | 83 | (9.0) | 0.28 |

| Other comorbidity | 265 | (28.9) | 257 | (27.8) | 0.61 |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Population of county of residence | |||||

| 1,000,000 or more | 512 | (55.8) | 493 | (53.3) | |

| 250,000 to 999,999 | 174 | (19.0) | 211 | (22.8) | |

| 0 to 249,999 | 232 | (25.3) | 221 | (23.9) | 0.13 |

| Median household income in census tract of residence (US$) | |||||

| 25,000 or less | 89 | (9.7) | 107 | (11.6) | |

| > 25,000 to 40,000 | 273 | (29.7) | 325 | (35.1) | |

| > 40,000 to 60,000 | 328 | (35.7) | 305 | (33.0) | |

| > 60,000 | 221 | (24.1) | 180 | (19.5) | 0.02 |

| Hospital and physician characteristics | |||||

| Hospital academic affiliation | 505 | (55.0) | 453 | (49.0) | 0.03 |

| Hospital beds | |||||

| ≤ 148 | 202 | (45.0) | 247 | (55.0) | |

| 149 - 238 | 217 | (48.5) | 230 | (51.5) | |

| 239 - 342 | 241 | (54.0) | 205 | (46.0) | |

| ≥ 343 | 230 | (52.0) | 212 | (48.0) | |

| Unknown | 28 | (47.5) | 31 | (52.5) | 0.07 |

| Physician practice years | |||||

| ≤ 16 | 223 | (49.8) | 225 | (50.2) | |

| > 17 - 24 | 225 | (49.7) | 228 | (50.3) | |

| > 24 - 33 | 262 | (53.9) | 224 | (46.1) | |

| > 33 | 189 | (46.1) | 221 | (53.9) | |

| Unknown | 19 | (41.3) | 27 | (58.7) | 0.14 |

Selected race, ethnicity, marital status, and grade cells suppressed according to SEER-Medicare guidelines for reporting cell sizes < 11 patients. Ethnicity, like race, was not balanced across levels of IV (data not shown). Diagnosis year was balanced across levels of IV (data not shown).

Log-rank P value

We explored four other candidate instruments (urologist or radiation oncologist density, distance to nearest hospital or radiation facility, and urologist prior treatment preference); however, these instruments were weak (F statistic < 10). A fifth candidate instrument (urologist prior treatment preference) was infeasible in this cohort because a large portion of urologists treated < 5 patients.

We used the two-stage residual inclusion method for IV estimation [16]. Standard errors were obtained via bootstrapping with bias correction [17].

Simulation for Stage Misclassification

Because prognostically important discrepancies have been reported between pathologic and clinical staging for UCB, survival outcomes of BPT will appear worse than RC if adjusted for ‘SEER’ tumor stage as result of misclassification error. This discordance also makes stage endogenous to the instrumental variable; as recorded by SEER, stage is associated with both treatment assignment and survival.

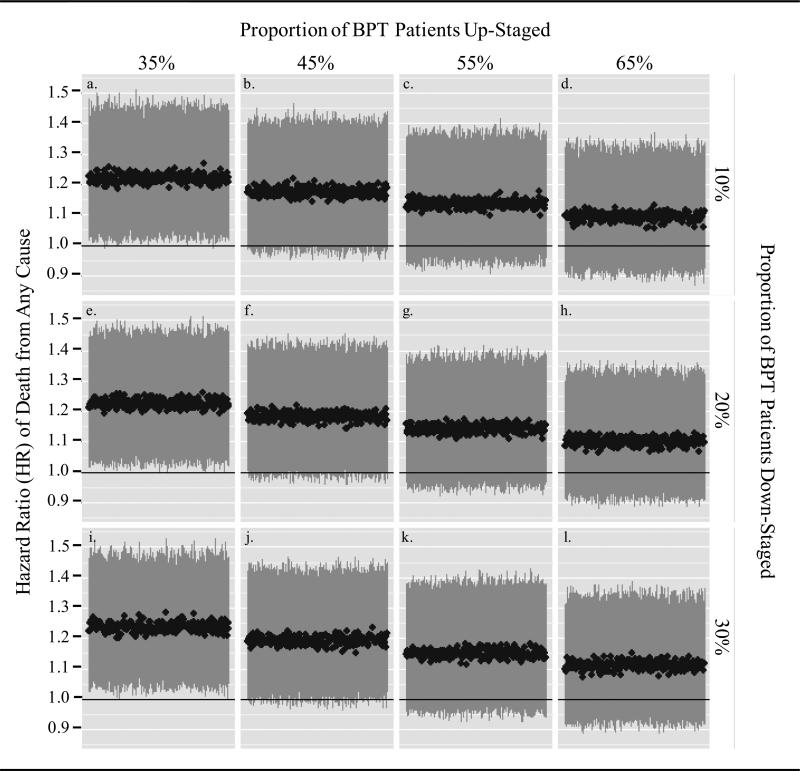

To examine the sensitivity of traditional regression survival estimates to stage misclassification, we evaluated what affect pathologic up- and down-staging of BPT patients would have on the hazard ratio (HR) estimates of the association between BPT and survival, based on multivariable models adjusted for measured covariates and ‘SEER’ stage. Table 3 presents multivariable models without and with adjustment for stage. We estimated the plausible range of stage misclassification on the basis of a large, multi-institutional cohort of patients who underwent clinical staging by TUR and subsequent pathologic staging by RC (53.5% of clinical stage 2 patients were up-staged to pathologic stage 3 and 20.5% of clinical stage 3 patients were down-staged to pathologic stage 2) [3]. We developed 12 scenarios in which we varied the proportion of BPT patients up-staged (35%, 45, 55, and 65% of stage 2 BPT patients) and down-staged (10%, 20%, and 30% of stage 3 BPT patients). In each scenario, we simulated 250 datasets in which the designated proportions of BPT patients were randomly up-staged or down-staged.

Table 3.

Significant Covariates* Associated with Death from Any Cause or from Bladder Cancer after Multivariable Model Risk Adjustment (Cox Proportional Hazards Regression)

| Multivariable Model Adjusted for Covariates* without Stage | Multivariable Model Adjusted for Covariates* with Stage | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death from Any Cause | Death from Bladder Cancer | Death from Any Cause | Death from Bladder Cancer | |||||

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| BPT, relative to RC | 1.26 (1.07 - 1.50) | 0.006 | 1.28 (0.98 - 1.68) | 0.068 | 1.42 (1.21 - 1.67) | <0.001 | 1.53 (1.16 - 2.02) | 0.003 |

| Stage III, relative to II | -- | -- | 1.65 (1.46 - 1.85) | <0.001 | 1.98 (1.75 - 2.24) | <0.001 | ||

| Age (each additional year) | 1.04 (1.03 - 1.05) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.01 - 1.04) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.03 - 1.05) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.01 - 1.04) | <0.001 |

| Female, relative to male | 0.91 (0.80 - 1.03) | 0.13 | 1.26 (1.06 - 1.49) | 0.009 | 0.91 (0.80 - 1.05) | 0.201 | 1.27 (1.05 - 1.54) | 0.015 |

| Not married, relative to married | 1.14 (1.03 - 1.27) | 0.015 | 1.02 (0.89 - 1.18) | 0.752 | 1.14 (1.02 - 1.28) | 0.021 | 1.01 (0.87 - 1.17) | 0.92 |

| Comorbid disease | ||||||||

| Hypertension, relative to none | 1.17 (1.03 - 1.32) | 0.018 | 1.18 (1.02 - 1.37) | 0.029 | 1.15 (1.00 - 1.31) | 0.048 | 1.16 (0.99 - 1.35) | 0.065 |

| COPD, relative to none | 1.21 (1.05 - 1.40) | 0.009 | 1.06 (0.88 - 1.27) | 0.53 | 1.22 (1.06 - 1.41) | 0.006 | 1.07 (0.89 - 1.28) | 0.46 |

| Anemia | 1.15 (1.02 - 1.31) | 0.027 | 1.12 (0.95 - 1.31) | 0.17 | 1.15 (1.02 - 1.31) | 0.028 | 1.13 (0.96 - 1.33) | 0.14 |

| Perivascular, relative to none | 1.10 (0.97 - 1.25) | 0.127 | 1.11 (0.94 - 1.31) | 0.21 | 1.13 (1.01 - 1.28) | 0.040 | 1.15 (0.98 - 1.34) | 0.08 |

| CHF, relative to none | 1.29 (1.09 - 1.52) | 0.002 | 1.25 (1.00 - 1.56) | 0.047 | 1.28 (1.08 - 1.53) | 0.005 | 1.26 (0.99 - 1.59) | 0.059 |

| Electrolyte abnormality, relative to none | 1.25 (1.08 - 1.44) | 0.003 | 1.14 (0.89 - 1.45) | 0.29 | 1.23 (1.06 - 1.43) | 0.008 | 1.09 (0.86 - 1.39) | 0.48 |

| Other comorbidity, relative to no other | 1.27 (1.13 - 1.41) | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.13 - 1.54) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.09 - 1.37) | 0.001 | 1.27 (1.08 - 1.49) | 0.003 |

Adjusted for age, race, ethnicity, marital status, tumor grade, comorbidity, diagnosis year, SEER registry, area population, median income, physician practice years, hospital beds, and hospital academic affiliation.

Abr: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHF, congestive heart failure

Statistical modeling and simulation studies were performed using SAS version 9.2 (Cary, North Carolina) and R version 2.13.0 (Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents selected baseline characteristics of the 1426 patients received RC and the 417 patients who received BPT. Patients who received BPT were older, more likely to be male, and more likely to have a prior history of cardiac arrhythmia, perivascular disease, congestive heart failure, or valvular disease.

Table 2 compares patients groups by whether the local area cystectomy rate was below or above the median rate. Prognostically important covariates (i.e. age, history of comorbid disease) were well balanced. The most prominent characteristic not balanced was race.

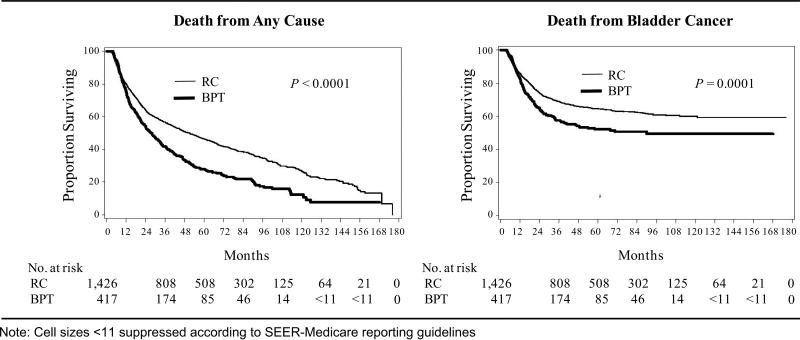

Figure 1 shows unadjusted Kaplan–Meier plots for survival in the two treatment groups. Unadjusted 5-year OS was 46.5% in the RC group versus 27.9% in the BPT group and 5-year BCSS was 64.5% in the RC group versus 52.2% the BPT group.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted Kaplan Meier Estimates of the Proportion Surviving after RC and BPT

Table 4 presents hazard ratios associated with BPT relative to RC from univariate, multivariable, propensity score, and IV analysis. In unadjusted Cox models, BPT was associated with increased death from any cause (HR 1.54; 95% CI, 1.33 - 1.77) and from bladder cancer (HR 1.42; 95% CI, 1.17 - 1.73). After adjusting for measured confounders using multivariable and propensity score-based methods, BPT remained associated with increased death from any cause (propensity score adjusted HR 1.26; 95% CI 1.05 - 1.53) and from bladder cancer (propensity score adjusted HR 1.31; 95% CI 0.97 - 1.77). Instrumental variable analysis produced substantially attenuated survival estimates of BPT versus RC (HR for death from any cause 1.06; 95% CI, 0.78 - 1.31; HR for death from bladder cancer 0.94; 95% CI 0.55 - 1.18). Parallel estimation of hazards using AFT models revealed findings consistent in direction and significance with Cox models (Table 4).

Table 4.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Hazard Ratios Associated with BPT relative to RC

| Cox Proportional Hazards Repression | Accelerated Failure Time Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death from any cause HR (95% CI) | Death from bladder cancer HR (95% CI) | Death from any cause HR (95% CI) | Death from bladder cancer HR (95% CI) | |

| Unadjusted model | 1.54 (1.33 - 1.77) | 1.42 (1.17 - 1.73) | 1.75 (1.51 - 2.03) | 2.27 (1.65 - 3.11) |

| Multivariable model | 1.26 (1.07 - 1.50) | 1.28 (0.98 - 1.68) | 1.33 (1.15 - 1.53) | 1.66 (1.21 - 2.27) |

| Propensity score model | 1.26 (1.05 - 1.53) | 1.31 (0.97 - 1.77) | 1.36 (1.16 - 1.59) | 1.79 (1.27 - 2.51) |

| Inverse probability-weighted | 1.27 (1.06 - 1.53) | 1.34 (1.02 - 1.77) | 1.39 (1.26 - 1.53) | 1.88 (1.55 - 2.27) |

| Instrumental variable model* | 1.06 (0.78 - 1.31) | 0.94 (0.55 - 1.18) | 1.13 (0.77 - 1.47) | 1.02 (0.34 - 1.52) |

Note: The hazard ratio (HR) is an estimate of the hazard of death in the BPT group versus the RC group. A hazard ratio > 1 indicates worse survival in the BPT group. Multivariable and propensity score models adjusted for all covariates except SEER stage. IV model adjusted for all covariates except SEER registry and SEER tumor stage (eg. tumor stage was excluded from the IV analysis because it was endogenous to the instrument; as clinical and pathologic stage is recorded by SEER in a single variable, stage is associated with treatment and outcomes).

Simulation studies for 12 scenarios of stage misclassification are presented in Figure 2 and are based on the multivariable HR for death from any cause for BPT versus RC, adjusted for all covariates and SEER stage (HR 1.42, 95% CI, 1.21 – 1.67). Stage 3 was reported in 41% of RC and 16% of BPT patients, though SEER reports pathologic stage for RC patients and clinical stage for BPT patients. Not surprisingly, the HR estimate adjusted for all covariates and SEER stage is increased in comparison to estimates from adjusted models without SEER stage (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Effect of Pathologic Up-staging and Down-staging of BPT Patients on the Hazard Ratio of Death from Any Cause Adjusted for Covariates and Tumor Stage

In 250 simulated datasets where 55% of BPT patients were randomly up-staged from stage 2 to stage 3 (a level of up-staging consistent with prior evidence [3] for pathologic understaging at TUR), we no longer observed a significant difference in mortality between BPT and RC in any simulations based on traditional multivariable regression (e.g. the lower bound of 95% CI crossed 1), regardless of the proportion of BPT patients randomly down-staged (Fig. 2, panels c, g, and k). Simulations for the influence of stage misclassification on the HR for death from bladder cancer were consistent with simulations for death from any cause (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The comparison of survival outcomes after surgical versus organ preserving treatment for muscle-invasive UCB illustrates the particular challenges of uncontrolled confounding and variable misclassification in observational cancer CER. In this registry cohort, treatment assignment is influenced by severe selection effects and outcomes are vulnerable to systematic misclassification of tumor stage.

We observed differences in mortality estimates derived from traditional regression models (that only adjust for measured confounding) and IV models (that theoretically adjust for both measured and unmeasured confounding). Traditional multivariable or propensity score methods attenuated the unadjusted association between BPT and increased mortality, whereas the IV analysis demonstrated no survival difference between treatments.

Why might traditional regression methods reveal mortality differences between RC and BPT? One explanation may be that surgical resection of tumor is a critical component of curative therapy and leads to better survival outcomes compared to bladder preservation [18]. An alternative explanation, however, is that residual unmeasured bias remains in the comparison of RC to BPT. Patients treated with BPT in this cohort were older and more likely to have congestive heart failure, arrhythmias, and perivascular disease, which is consistent with confounding by indication. The severity of comorbidity in the BPT group, however, is not available from SEER-Medicare data, nor is other important unmeasured confounders, such as performance status or cognitive impairment. Traditional regression methods may yield effect estimates that are biased upwards because of uncontrolled confounding. Moreover, traditional regression may introduce bias when important measured confounders, like tumor stage, are misclassified.

Can IV analyses be relied upon to disentangle the degree of confounding present in the comparison of RC to BPT? While the instrument theoretically balanced unmeasured variables between patient groups, this relies on the unverifiable assumption that the instrument is not systematically related to unmeasured confounding variables. It is possible, for example, that patients living in high cystectomy areas also have greater access to health care in general. IV methods may yield effect estimates that are biased downwards if unmeasured correlates of survival, like access to health care, are associated with the instrument. We mitigated this risk by also adjusting for neighborhood socioeconomic status (though associations with unmeasured confounding variables may remain). Moreover, the results of the IV analysis have external validity; BPT efficacy trials, which have included patients with T2 to T4a disease, have achieved survival rates comparable to those reported in contemporary cystectomy series [2,19]. Ultimately, the degree to which IV analyses should be relied upon in any particular comparison depends largely on the degree to which the underlying assumptions are believed.

Beyond possible differences in confounding control, the two analytic techniques produce effect estimates that apply to different patient populations. Traditional regression estimates average treatment effects for a population of patients while IV methods apply to the set of ‘marginal patients’ whose treatment choice depends on the instrument; in this case, to those patients who would be treated in high cystectomy areas but not in low cystectomy areas [20]. Previous research has shown that radical cystectomy is underused, particularly among older patients, those with greater comorbidities, and those who live far from cystectomy-performing hospitals; such patients could be affected by a cystectomy rate increase [4]. Our IV results suggest that survival outcomes after RC versus BPT among these patients may be similar (provided they are candidates for either treatment).

When tumor stage was incorporated into traditional multivariable survival models, the relative mortality difference between BPT and RC increased in comparison to multivariable models without stage. Prognostically important discordance between clinical and pathologic staging has been shown for lung and prostate cancer and affects the interpretation of studies that compare radical surgery to alternative treatments without a primary resectional component [21,22]. In bladder cancer, survival outcomes of BPT appear worse if adjusted for ‘SEER’ tumor stage because of systematic stage misclassification. In sensitivity analyses for stage misclassification, mortality differences between RC and BPT were no longer significant under plausible scenarios of pathologic up-staging and down-staging. Notably, the results of the simulation studies were directionally consistent with the results of the IV analyses.

Our results extend the work of previous studies that have examined alternative treatments for muscle-invasive UCB. These studies found that RC extended survival relative to radiation and/or chemotherapy or no further treatment [4,5]. In contrast, we attempted to mimic the design of a randomized trial of two curative approaches for muscle invasive UCB by comparing RC to BPT, a treatment alternative with curative intent that involves a specific regimen of tri-modality therapy. Differences in survival estimates between our work and that of others underscore how important the choice of the “comparator” is to both observational CER and randomized trials [23].

Our study is limited in that we did not compare BPT to neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to RC, which may improve survival over RC alone. We only identified a small number of patients in SEER-Medicare data who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. This group, surprisingly, had worse survival outcomes than the RC alone group, which possibly reflects uncertainty about who benefits from neoadjuvant chemotherapy and selection effects among those to whom it was delivered. Including such patients in the comparison of BPT to RC would inappropriately reduce the survival estimates of the RC group. In addition, we did not adjust for hospital/provider procedure volume because the two primary treatments under study are performed by different physicians and different health care facilities (i.e., RC is a hospital-based surgery while BPT involves outpatient radiotherapy and chemotherapy delivery).

In conclusion, we found that survival estimates in an observational cohort of patients who underwent RC versus BPT differ by analytic method. While the results of the IV analyses and sensitivity analyses for stage misclassification may cast doubt on the findings of the traditional regression models, we also caution that effect estimates from the IV models are conditional on strong assumptions and are generalizable to those patients whose treatment choice depends on the instrument (e.g. those who would be affected by an increase in cystectomy rates). In the absence of randomized trials, careful application and interpretation of analytic methods to control for confounding can provide insights into treatment effectiveness.

Acknowledgement

This study used the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–Medicare database. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute (NCI), the Office of Research, Development and Information, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Information Management Services (IMS), Inc., and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER–Medicare database. We thank Robert Sunderland, MS, for programming assistance. We gratefully acknowledge the mentorship of Thomas Ten Have, PhD, MPH.

Source of financial support: Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RC4-CA155809), the National Cancer Institute (RC2-CA148310, K12-CA076931, 1K07CA163616), the National Cancer Institute and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (1K07CA151910), the US Public Health Service (P30-CA016520), and the Thomas B. and Jeannette E. Laws McCabe Fund. Prior Presentation: Presented in part at the American Society for Radiation Oncology Annual Meeting, Miami, Fl, October, 2011.

ROLE OF THE SPONSORS: The funding agencies did not participate in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors declare no actual or potential conflicts.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: Dr. Bekelman had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Bekelman, Handorf, Guzzo, Ten Have, Polsky, Mitra

Acquisition of data: Bekelman, Resnick, Swisher-McClure, Handorf

Drafting of the manuscript: Bekelman, Handorf, Polsky, Mitra

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors

Statistical analysis: Handorf, Bekelman, Ten Have, Polsky, Mitra

Obtained funding: Bekelman, Guzzo, Polsky

Administrative, technical, or material support: Bekelman

Study supervision: Bekelman, Ten Have, Polsky, Mitra

DISCLAIMER: The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors.

References

- 1.Efstathiou J, Spiegel DY, Shipley WU, et al. Long-term outcomes of selective bladder preservation by combined-modality therapy for invasive bladder cancer: The MGH experience. Eur urol. 2012;61:705–11. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.James ND, Hussain SA, Hall E, et al. Radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1477–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Svatek RS, Shariat SF, Novara G, et al. Discrepancy between clinical and pathological stage: external validation of the impact on prognosis in an international radical cystectomy cohort. BJU Int. 2011;107(6):898–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gore JL, Litwin MS, Lai J, et al. Use of radical cystectomy for patients with invasive bladder cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:802–11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schrag D, Mitra N, Xu F, et al. Cystectomy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: patterns and outcomes of care in the Medicare population. Urology. 2005;65:1118–25. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollenbeck BK, Wei Y, Birkmeyer JD. Volume, process of care, and operative mortality for cystectomy for bladder cancer. Urology. 2007;69:871–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris D, Coffey R. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Homer D, Lemeshaw S. Applied Survival Analysis: Regression modeling of time to event data. 1st ed. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenbaum P, Robin D. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. J Am Stat Assoc. 1984;79:516–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubin DB, Thomas N. Matching using estimated propensity scores: relating theory to practice. Biometrics. 1996;52:249–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis LH, Hammill BG, Eisenstein EL, et al. Using inverse probability-weighted estimators in comparative effectiveness analyses with observational databases. Med Care. 2007;45(10 Suppl. 2):S103–7. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31806518ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin DY, Wei LJ. The robust inference for the proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84:1074–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collett D. Modelling Survival Data in Medical Research. Second Edition Chapman and Hall/CRC; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei L. The accelerated failure time model: a useful alternative to the Cox regression in survival analysis. Stat Med. 1992;11:1871–9. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brookhart MA, Rassen JA, Schneeweiss S. Instrumental variable methods in comparative safety and effectiveness research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:537–54. doi: 10.1002/pds.1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terza JV, Basu A, Rathouz PJ. Two-stage residual inclusion estimation: addressing endogeneity in health econometric modeling. J Health Econ. 2008 May;27:531–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman & Hall; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simone G, Gallucci M. Multimodality treatment versus radical cystectomy: Bladder sparing at cost of life? Eur Urol. 2012;61:712–4. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufman DS, Shipley WU, Feldman AS. Bladder cancer. Lancet. 2009;374:239–49. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris KM, Remler DK. Who is the marginal patient? Understanding instrumental variables estimates of treatment effects. Health Services Research. 1998;33(5 Pt 1):1337–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stiles BM, Servais EL, Lee PC, et al. Point: Clinical stage IA non-small cell lung cancer determined by computed tomography and positron emission tomography is frequently not pathologic IA non-small cell lung cancer: the problem of understaging. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooke EW, Shrieve DC, Tward JD. Clinical Versus Pathologic Staging for Prostate Adenocarcinoma: How Do They Correlate? Am J Clin Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31821241fc. volume:page range. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chokshi DA, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. Designing comparative effectiveness research on prescription drugs: lessons from the clinical trial literature. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010 Oct;29:1842–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]