Abstract

The pleiotropic effects of statins, especially the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory ones, indicate that their therapeutic potential might extend beyond cholesterol lowering and cardiovascular disease to other inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis. Therefore, we undertook a prospective cohort study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of simvastatin used for inflammation control in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. One hundred patients with active rheumatoid arthritis divided into two equal groups (the study one who received 20 mg/day of simvastatin in addition to prior DMARDs and the control one) were followed up over six months during three study visits. The results of the study support the fact that simvastatin at a dose of 20 mg/day has a low anti-inflammatory effect in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with a good safety profile.

1. Introduction

Since their discovery in 1976, 3-hydroxy-3methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (or statins) have emerged as the leading therapeutic regimen for treating hypercholesterolemia modifying, an important cardiovascular risk factor with subsequent reduction of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [1]. Numerous clinical studies have demonstrated the efficiency of statins in this context, in both primary [2–4] and secondary prevention strategies [5–17]. In parallel, it has become increasingly apparent that the beneficial effects of statins in cardiovascular pathology cannot be ascribed solely to their lipid-lowering properties, but also to another mode of action. These so-called “pleiotropic effects” which encompass modification of endothelial function, plaque stability and thrombus formation, and anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties indicate that the therapeutic potential of statins might extend beyond cholesterol lowering and cardiovascular disease to other inflammatory disorders or conditions such as transplantation, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and chronic kidney disease [18]. Extensive in vitro [19, 20] and in vivo [21–25] data sets support this statement.

Rheumatoid arthritis, the commonest of the inflammatory arthritides, is a chronic, systemic, inflammatory disorder which has as primary target the synovial tissue. The characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis is the persistent inflammation of the peripheral joints which leads to pain, stiffness, and swelling, with their gradual destruction, and, in time, it may lead to joint deformities and functional disability. Although the majority of physicians' efforts had been targeted at symptom control and reduction of joint damage, it has been known for more than 50 years that rheumatoid arthritis is associated with significantly increased mortality rates compared with the general population [26]. An important part that accounts for this excess mortality is an increase in cardiovascular deaths [27]. Their increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [28] are primarily due to accelerated atherosclerosis [29] which develops due to a complex interaction between traditional risk factors (dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity) and those related to the inflammatory disease [30, 31].

Despite advances in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, its mortality does not appear to have significantly changed over the last few decades, highlighting the need for closer attention to prevention and treatment of cardiovascular events in these patients [32]. Thus, optimal treatment of rheumatoid arthritis should reasonably deal with vascular risk modification in addition to the well-recognized objectives of treatment, namely, to suppress inflammation, improve function, prevent articular damage, and modify psychosocial implications of the disease [33]. The already known cardiovascular protective effect together with the new emerged anti-inflammatory one may render statins an attractive adjunct therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Up to date, few clinical studies support this statement [34–39]; nevertheless, further clinical trials are required to verify whether more widespread use of statins should be recommended in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Therefore, we undertook a cohort prospective study which had as primary objectives the reduction in disease activity (measured by the proportion of patients meeting EULAR response criteria and the change in the DAS28 ESR scale, a validated composite disease activity score that incorporates erythrocyte sedimentation rate, patient global assessment of disease activity, visual analogue scale for pain, and tender and swollen joint count based on the evaluation of 28 joints) and the evaluation of the frequency and severity of adverse events; among the secondary outcome measures there were change in composite indices of disease activity assessment (DAS28 CRP, SDAI, and CDAI), change in clinical variables of disease activity (duration of morning stiffness, tender joint count, swollen joint count, HAQ-DI, measure of pain using a visual analogue scale, and patient and evaluator global assessments of disease activity), change in acute phase reactants (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate), change in rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies levels, and change in lipid profile and incidence of cardiovascular events.

2. Material and Methods

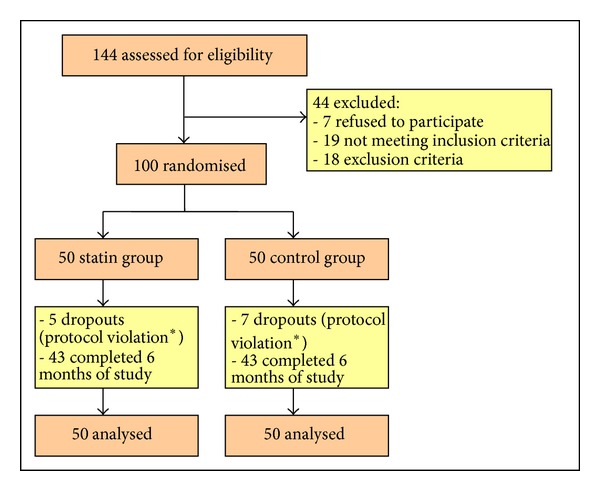

The clinical study was performed in Rheumatology Department of 3rd Medical Clinic of Emergency Clinical Hospital of Constanta from October 2008 to October 2009. From October 2008 to April 2009, 144 patients were screened (122 women and 22 men) (Figure 1). After giving the informed consent, we recruited 100 patients with ages between 18 and 80 years, meeting the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria, with active inflammatory disease (defined by disease activity score—DAS28—greater than 2.4) despite ongoing DMARD therapy, in adequate doses for at least 3 months for hydroxychloroquine, or 4 weeks for methotrexate, sulfasalazine, leflunomide, or etanercept. The exclusion criteria were diabetes, familial hypercholesterolaemia, use of oral prednisolone >10 mg/day (or doses ≤ 10 mg that were not stable for 4 weeks prior to screening visit), intra-articular cortisone injections within 4 weeks of study entry, statin therapy in the last 3 months prior to the study or with previous adverse reaction to statins, active or recent infection, myositis or elevation in creatine phosphokinase more than twice the upper limit of normal range, liver disease or abnormal liver function (transaminases > 2 times the upper limit of normal range), alcohol abuse, high serum creatinine level, chronic disorders other than rheumatoid arthritis affecting the joints, pregnancy or breastfeeding, and inclusion in other studies with investigational products. During the study, patients remained on all DMARDs in constant doses, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, drugs for comorbid conditions, and oral prednisolone (in doses ≤ 10 mg/day) from study entry.

Figure 1.

Study profile; *modification of DMARDs.

The 100 patients included in the study were divided into two equal groups (one group received simvastatin 20 mg/day in addition to prior DMARD therapy and the other, the control group, remained on the same DMARD therapy from the study entry) taking into account the indications of statin therapy [40]. The patients were followed for 6 months, during 3 study visits (at the inclusion, at 3 months, and at 6 months). At each visit, we performed anamnesis with visual analog pain scale, health assessment questionnaire disability index, patient's global assessment of disease activity, physical exam (measuring vital signs and clinical variables of disease activity), and evaluator global assessments of disease activity; we harvested blood samples for laboratory tests (hemogram, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, transaminases, creatine phosphokinase, and, only at inclusion and a 6-month visit: lipid profile, rheumatoid factor, anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, and serum creatinine levels) and we calculated disease activity indices, SDAI, CDAI, and DAS28 (using ESR and CRP). During the study and in the statin group, there were 5 dropouts (two in the first 3 months and three in the last 3 months of study), and 95 patients completed the 6-month visit, and in the control group, there were 7 dropouts (one in the first 3 months and six in the last 3 months of study), and 93 completed the 6-month visit (Figure 1).

All data were processed statistically with the aid of SPSS v.17.0. The data were analyzed by the intention-to-treat approach. Patients who did not complete 6 months of study were categorised as nonresponders. For change in laboratory variables, we accounted for dropouts by carrying their baseline value forward to 6 months, no change was assumed.

3. Results and Discussions

Baseline characteristics of the study groups are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the simvastatin and control groups except for: the lipid levels, proportion of hypertensive patients, proportion of patients with known cardiovascular disease, and the proportion of overweight patients (that were significantly higher in the simvastatin group as expected from the study design). The final results remained significant after the adjustment for these variables. Note that there were no significant differences between the two groups regarding the DMARDs use, thus removing an important element of confusion.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Variable | Simvastatin group | Control group | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.15 (9.49) | 56.48 (11.84) | 0.053 |

| Women | 44 (88%) | 42 (84%) | 0.566 |

| Rheumatoid factor positive | 25 (50%) | 27 (54%) | 0.69 |

| Anti-CCP antibody positive | 25 (50%) | 28 (56%) | 0.55 |

| Disease duration (years) | 10.62 (9.37) | 11.98 (11.86) | 0.956 |

| Methotrexate | 32 (64%) | 33 (66%) | 0.835 |

| Sulfasalazine | 20 (40%) | 19 (38%) | 0.838 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 10 (20%) | 11 (22%) | 0.807 |

| Leflunomide | 12 (24%) | 11 (22%) | 0.813 |

| Etanercept | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 |

| Oral prednisolone | 16 (32%) | 17 (34%) | 0.832 |

| Early morning stiffness (min)* | 12.80 (0–60) | 15.25 (0–60) | 0.446 |

| Tender joint count* | 7.02 (0–24) | 5.23 (0–25) | 0.168 |

| Swollen joint count* | 1 (0–8) | 0.6 (0–4) | 0.684 |

| VAS pain (mm) | 59.76 (18.90) | 50.50 (23.74) | 0.062 |

| Patient global assessment (mm) | 58.29 (14.47) | 54.75 (19.61) | 0.206 |

| Evaluator global assessment (mm) | 51.46 (9.10) | 47.50 (12.55) | 0.066 |

| HAQ-DI | 1.53 (0.51) | 1.36 (0.59) | 0.166 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 27.76 (15.81) | 27.58 (18.76) | 0.545 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L)* | 4.66 (0.36–36.67) | 4.71 (0.6–21.6) | 0.932 |

| DAS28 ESR | 4.44 (0.98) | 4.04 (1.00) | 0.074 |

| DAS28 CRP | 3.72 (1.00) | 3.39 (0.91) | 0.122 |

| SDAI | 19.51 (9.03) | 16.19 (8.02) | 0.085 |

| CDAI | 19.05 (9.10) | 15.73 (8.09) | 0.087 |

| Disease activity | |||

| LDA | 14 (28%) | 19 (38%) | 0.290 |

| MDA | 28 (56%) | 25 (50%) | 0.550 |

| HDA | 8 (16%) | 6 (12%) | 0.566 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 240.34 (40.33) | 197.15 (30.13) | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 155.07 (32.29) | 113.66 (25.30) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 62.33 (15.88) | 63.53 (19.06) | 0.758 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 133.58 (49.22) | 108.65 (48.29) | 0.024 |

| Total creatine phosphokinase (UI/L) | 73.12 (33.44) | 78 (51.74) | 0.788 |

| Alanine transaminase | 17.65 (6.82) | 22.74 (12.39) | 0.055 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 19.53 (5.45) | 21 (7.19) | 0.576 |

| Hypertension | 42 (84%) | 27 (54%) | 0.001 |

| Smokers | 10 (20%) | 9 (18%) | 0.8 |

| Ex-smokers | 2 (4%) | 3 (6%) | 0.648 |

| Overweight | 26 (52%) | 16 (32%) | 0.044 |

| Obesity | 15 (30%) | 13 (26%) | 0.658 |

| Previous stroke | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 0.56 |

| Coronary heart disease | 10 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 0.001 |

Between the breaks there are standard deviations or percents unless otherwise indicated; *minimal and maximal values of the variable; LDA: low disease activity; MDA: moderate disease activity; HDA: high disease activity.

Table 2 documents outcomes after 3 and 6 months of study.

Table 2.

Differences after 3 and 6 months of treatment.

| Variable | Follow-up visit | Simvastatin group | Control group | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early morning stiffness (min) | 3 month | 0.244 (−5.346; 5.834) | −1.125 (−9.962; 7.712) | 0.63 |

| 6 month | −3.536 (−7.701; 0.628) | −2.25 (−10.804; 6.304) | 0.996 | |

| Tender joint count | 3 month | −3 (−4.894; − 1.106) | −0.225 (−2.591; 2.141) | 0.03 |

| 6 month | −1.414 (−3.513; 0.684) | 1.650 (−1.009; 4.309) | 0.243 | |

| Swollen joint count | 3 month | −0.561 (−1.143; 0.021) | 0.275 (−0.431; 0.981) | 0.068 |

| 6 month | −0.341 (−0.808; 0.125) | 0.050 (−0.425; 0.525) | 0.288 | |

| VAS pain (mm) | 3 month | −1.219 (−8.762; 6.323) | 3.75 (−4.561; 12.061) | 0.888 |

| 6 month | −1.219 (−7.421; 4.982) | 4.500 (−4.745; 13.745) | 0.481 | |

| Patient global assessment (mm) | 3 month | −4.39 (−10.255; 1.475) | 0.25 (−6.084; 6.584) | 0.273 |

| 6 month | −2.926 (−8.714; 2.861) | −5.00 (−13.900; 3.900) | 0.196 | |

| Evaluator global assessment (mm) | 3 month | −7.561 (−10.620; −4.502) | 3 (−0.255; 6.255) | <0.001 |

| 6 month | −8.049 (−12.412; −3.685) | 1.500 (−3.279; 6.279) | 0.007 | |

| HAQ-DI | 3 month | −0.064 (−0.172; 0.043) | −0.122 (−0.288; 0.043) | 0.353 |

| 6 month | −0.153 (−0.283; −0.023) | −0.019 (−0.194; 0.154) | 0.149 | |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 3 month | −0.926 (−4.653; 2.799) | 2.125 (−2.712; 6.962) | 0.203 |

| 6 month | 2.829 (−1.046; 6.705) | 3.800 (−1.018; 8.618) | 0.751 | |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 3 month | 0.961 (−0.178; −2.101) | 3.767 (1.506; −6.027) | 0.055 |

| 6 month | 1.676 (−0.833; 4.186) | 2.57 (0.641; 4.499) | 0.687 | |

| DAS28 ESR | 3 month | −0.56 (−0.849; −0.270) | 0.076 (−0.312; 0.465) | 0.009 |

| 6 month | −0.313 (−0.641; 0.013) | 0.073 (−0.391; 0.537) | 0.171 | |

| DAS28 CRP | 3 month | −0.484 (−0.771; −0.196) | 0.090 (−0.309; 0.491) | 0.02 |

| 6 month | −0.295 (−0.637; 0.045) | 0.098 (−0.334; 0.531) | 0.151 | |

| SDAI | 3 month | −4.708 (−6.889; −2.527) | 0.951 (−2.061; 3.963) | 0.003 |

| 6 month | −2.466 (−5.257; 0.324) | 1.807 (−1.939; 5.553) | 0.067 | |

| CDAI | 3 month | −4.805 (−6.972; −2.637) | 0.575 (−2.397; 3.547) | 0.004 |

| 6 month | −2.634 (−5.355; 0.086) | 1.55 (−2.139; 5.239) | 0.068 | |

| EULAR response | 3 month | 16 (32%) | 7 (14%) | 0.033 |

| 6 month | 15 (30%) | 11 (22%) | 0.364 | |

| Attendance to visit | 3 month | 48 (96%) | 49 (98%) | 0.560 |

| 6 month | 45 (90%) | 43 (86%) | 0.540 |

Between the breaks, there are 95% confidence interval or percents.

After 3 months of study, DAS28 ESR improved significantly (P = 0.009) in the statin group (−0.560; 95% CI = −0.849, −0.270; P < 0.001) when compared to the control one (0.076; 95% CI = −0.312, 0.465; P = 0.693; difference between groups = −0.636; 95% CI = −1.112, −0.160). But, in the following 3 months, DAS28 ESR recorded a significant increase in the statin group (0.24; 95% CI 0.012, 0.479; P = 0.039), while in the control group, it remained practically unchanged (−0.003; 95% CI −0.441, 0.434; P = 0.987), and so, the final benefic effect of simvastatin on this index was reduced. After 6 months of study the decreasing tendency of DAS28 ESR in the statin group (−0.313; 95% CI = −0.641, 0.013; P = 0.06) compared with the slight increasing tendency in the control group (0.073; 95% CI = −0.391, 0.537; P = 0.752) did not achieve statistical significance (mean difference between groups = 0.386; 95% CI = −0.170, 0.943; P = 0.171).

Regarding EULAR response criteria, after 3 months of study, moderate or good DAS28 responses were achieved in 16 of 50 (32%) patients allocated simvastatin compared with 7 of 50 (14%) patients in the control group (OR 2.89; 95% CI 1.06–7.82; P = 0.03). At the end of the study, there was no significant difference between the number of patients who achieved EULAR response criteria in the statin group—15 (30%), and those from the control group—11 (22%) (OR 1.51; 95% CI 0.61–3.74; P = 0.362). There were no significant differences between the two groups regarding the number of patients who completed the study (90% in the statin group versus 86% in the control one (P = 0.558)).

After 3 months of treatment, in the statin group, there was a significant improvement in DAS28 CRP (difference between groups = −0.574; 95% CI = −1.058, −0.091; P = 0.02), SDAI (difference between groups = −5.659; 95% CI = −9.307, −2.012; P = 0.003), CDAI (difference between groups = −5.379; 95% CI= −8.987, −1.772; P = 0.004), evaluator global assessment of disease activity (difference between groups = −10.560; 95% CI = −14.955, −6.166; P < 0.001), and tender joint count (difference between groups = −2.775; 95% CI = −5.750, 0.200; P = 0.03); other variables (swollen joint count, visual analogue scale for pain, patient global assessment of disease activity, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate) tended to decrease more in the simvastatin group compared to the control one, without reaching statistical significance.

After 6 months of treatment there was no significant difference between the disease activity variables in the two groups, except for evaluator global assessment of disease activity (difference between groups = −9.54; 95% CI = −15.913, −3.184; P = 0.007). The decrease of early morning stiffness, tender joint count, swollen joint count, HAQ-DI, VAS pain, DAS28 CRP, SDAI, and CDAI was more pronounced in the simvastatin group, and the levels of CRP and ESR increased less compared to those in the control group.

These results show that a small daily dose of simvastatin has some beneficial effects on clinical and biological parameters of disease activity in patients with active forms of rheumatoid arthritis despite DMARDs therapy, but without statistical significance. The anti-inflammatory effect of simvastatin was inferior to that of atorvastatin in TARA study [38], but we have to take into account the difference between the pharmacokinetic properties of these two statins (despite the fact that simvastatin is more lipophilic than atorvastatin, its oral absorption is inferior and has a grater variance when compared to that of atorvastatin—42.5% ±42.5 versus 57.5% ±17.5—and more importantly, the plasma half time of simvastatin is only 1.9 hr, whereas the plasma halftime of atorvastatin is 14 hr) and the lower dose used (20 mg of simvastatin versus 40 mg of atorvastatin). Another difference can emerge from the fact that in TARA study in the atorvastatin group, a significant higher number of patients were on methotrexate compared to the placebo lot (P < 0.07).

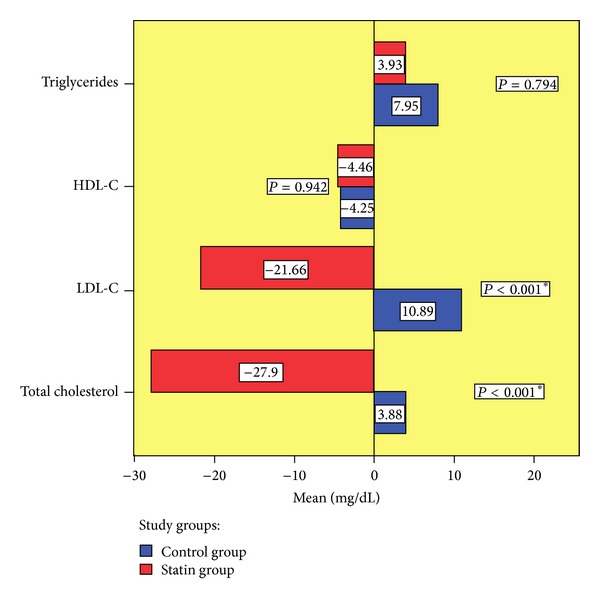

The evolution of lipid profiles after 6 months of study is presented in Figure 2. Total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol were significantly reduced in simvastatin group compared to control group (total cholesterol − mean difference between groups = 31.77 mg/dL; 95% CI = 19.311, 44.243; P < 0.001; LDL-cholesterol − mean difference between groups = 32.54 mg/dL; 95% CI = 21.109, 43.972; P < 0.001). Regarding HDL cholesterol and triglycerides, there were no significant differences between the two groups. These results are inferior to the ones obtained in other clinical trials with simvastatin in patients without rheumatoid arthritis. For example, in 4S Study [11] a daily dose of 20 mg simvastatin (Zocor, Merck Sharp & Dohme) for 6 weeks significanty (P < 0.0001) decreased the level of total cholesterol (by 28%) and LDL cholesterol (by 38%) and increased the level of HDL cholesterol (by 8%). So we can conclude that statins maintain their hypocholesterolemic effect in context of high-grade inflammatory state like that present in rheumatoid arthritis, but their efficacy may be reduced when compared with that in other patients; so, there may be need for increased dose of statins for the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Figure 2.

Evolution of lipid profile.

During the study, simvastatin was well tolerated. Study dropouts were due to protocol violation, namely, the necessity of DMARDs modification and not because of simvastatin use. Adverse events were mild and arose with similar frequency in both groups (Table 3). In particular, no significant liver function or muscle abnormality was detected in those given simvastatin. Also, during the study there were no significant cardiovascular events.

Table 3.

Adverse events.

| Adverse event | Simvastatin group | Control group | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elevated aspartate aminotransferase | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 0.558 |

| Elevated alanine aminotransferase | 1 (2%) | 5 (10%) | 0.092 |

| Elevated creatine phosphokinase | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 0.558 |

| Myalgia | 2 (4%) | 3 (6%) | 0.646 |

| Muscle weakness | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 0.558 |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (8%) | 6 (12%) | 0.505 |

| Nausea | 6 (12%) | 4 (8%) | 0.505 |

| Constipation | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0.315 |

| Diarrhea | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0.315 |

| Flatulence | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 0.558 |

| Asthenia | 2 (4%) | 4 (8%) | 0.400 |

| Dizziness | 1 (2%) | 3 (6%) | 0.307 |

| Headache | 2 (4%) | 4 (8%) | 0.400 |

| Allergy | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0.315 |

4. Conclusions

Simvastatin at a dose of 20 mg/day has small anti-inflammatory effects in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. These effects do not have the magnitude to justify neither the use of statins instead of DMARDs therapy nor their routine use in all patients with rheumatoid arthritis. But thanks to good safety profile, easy administration, and the existence of a broad experience regarding their use in clinical practice, statins are particularly attractive therapeutic agents, so that even a modest efficacy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in association with the reduction of cardiovascular risk can lead to a beneficial therapeutic ratio. This can make statins become particularly useful as adjuvant therapy associated with other conventional therapeutic methods used in rheumatoid arthritis, especially in patients with dyslipidaemia, where they should be the first choice of treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study received funding from CNCSIS, research Grant TD no. 199/2008. The authors thank all the members of the Rheumatology Department of Emergency County Hospital of Constanta, especially Dr. Ramazan Ana-Maria and Dr. Buriu Mihaela from Medstar 2000 Center for their support.

Abbreviations

- CDAI:

Clinical disease activity index

- DAS28 CRP:

Disease activity score based on the count of 28 joint and C-reactive protein

- DAS28 ESR:

Disease activity score based on the count of 28 joint and erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- DMARDs:

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

- EULAR:

European league against rheumatism

- HAQ-DI:

Health assessmentquestionnaire-disability Index

- HMG-CoA:

3-Hydroxy-3methylglutaryl-coenzyme A

- SDAI:

Simplified disease activity index.

References

- 1.McCarey DW, Sattar N, McInnes IB. Do the pleiotropic effects of statins in the vasculature predict a role in inflammatory diseases? Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2005;7(2):55–61. doi: 10.1186/ar1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, et al. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279(20):1615–1622. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.20.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;333(20):1301–1307. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sever PS, Dahlöf B, Poulter NR, et al. Prevention of coronary and stroke events with atorvastatin in hypertensive patients who have average or lower-than-average cholesterol concentrations, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial—Lipid Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2003;361(9364):1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12948-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown G, Albers JJ, Fisher LD, et al. Regression of coronary artery disease as a result of intensive lipid-lowering therapy in men with high levels of apolipoprotein B. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;323(19):1289–1298. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011083231901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jukema JW, Bruschke AVG, van Boven AJ, et al. Effects of lipid lowering by pravastatin on progression and regression of coronary artery disease in symptomatic men with normal to moderately elevated serum cholesterol levels: the Regression Growth Evaluation Statin Study (REGRESS) Circulation. 1995;91(10):2528–2540. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.10.2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herd JA, Ballantyne CM, Farmer JA, et al. Effects of fluvastatin on coronary atherosclerosis in patients with mild to moderate cholesterol elevations (lipoprotein and coronary atherosclerosis study [LCAS]) American Journal of Cardiology. 1997;80(3):278–286. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P, et al. Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(9):1071–1080. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maycock CAA, Muhlestein JB, Horne BD, et al. Statin therapy is associated with reduced mortality across all age groups of individuals with significant coronary disease, including very elderly patients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;40(10):1777–1785. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaughan CJ, Murphy MB, Buckley BM. Statins do more than just lower cholesterol. The Lancet. 1996;348(9034):1079–1082. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)05190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedersen TR. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) The Lancet. 1994;344(8934):1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LIPID Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;339(19):1349–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811053391902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Waters DD, et al. Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352(14):1425–1435. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedersen TR, Faergeman O, Kastelein JJP, et al. High-dose atorvastatin vs usual-dose simvastatin for secondary prevention after myocardial infarction: the IDEAL study: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294(19):2437–2445. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.19.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335(14):1001–1009. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins R, Armitage J, Parish S, Sleight P, Peto R. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20 536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2002;360(9326):7–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes the MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(13):1711–1718. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.13.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steffens S, Mach F. Drug Insight: immunomodulatory effects of statins—potential benefits for renal patients? Nature Clinical Practice Nephrology. 2006;2(7):378–387. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grip O, Janciauskiene S, Lindgren S. Atorvastatin activates PPAR-γ and attenuates the inflammatory response in human monocytes. Inflammation Research. 2002;51(2):58–62. doi: 10.1007/BF02684000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilgendorff A, Muth H, Parviz B, et al. Statins differ in their ability to block NF-κB activation in human blood monocytes. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2003;41(9):397–401. doi: 10.5414/cpp41397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung BP, Sattar N, Crilly A, et al. A novel anti-inflammatory role for simvastatin in inflammatory arthritis. Journal of Immunology. 2003;170(3):1524–1530. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sparrow CP, Burton CA, Hernandez M, et al. Simvastatin has anti-inflammatory and antiatherosclerotic activities independent of plasma cholesterol lowering. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2001;21(1):115–121. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwak B, Mulhaupt F, Myit S, Mach F. Statins as a newly recognized type of immunomodulator. Nature Medicine. 2000;6(12):1399–1402. doi: 10.1038/82219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weitz-Schmidt G, Welzenbach K, Brinkmann V, et al. Statins selectively inhibit leukocyte function antigen-1 by binding to a novel regulatory integrin site. Nature Medicine. 2001;7(6):687–692. doi: 10.1038/89058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McInnes IB, Leung BP, Liew FY. Cell-cell interactions in synovitis. Interactions between T lymphocytes and synovial cells. Arthritis Research. 2000;2(5):374–378. doi: 10.1186/ar115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cobb S, Anderson F, Bayer W. Lenght of life and cause of death in rheumatoid arthritis. The New England Journal of Medicine . 1953;249(14):553–556. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195310012491402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinblatt ME, Kuritzky L. RAPID: rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of Family Practice. 2007;56(4, supplement):S1–S7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solomon DH, Karlson EW, Rimm EB, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in women diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation. 2003;107(9):1303–1307. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000054612.26458.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Doornum S, McColl G, Wicks IP. Accelerated atherosclerosis: an extraarticular feature of rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2002;46(4):862–873. doi: 10.1002/art.10089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solomon DH, Greenberg J, Reed G, et al. Cardiovascular risk among patients with RA in CORRONA: comparing the explanatory value of traditional cardiovascular risk factors with RA risk factors. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2008;67(supplement 2, article 482) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplan MJ. Cardiovascular disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2006;18(3):289–297. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000218951.65601.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: have we made an impact in 4 decades? Journal of Rheumatology. 1999;26(12):2529–2533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McInnes IB, McCarey DW, Sattar N. Do statins offer therapeutic potential in inflammatory arthritis? Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2004;63(12):1535–1537. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.022061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanda H, Hamasaki K, Kubo K, et al. Antiinflammatory effect of simvastatin in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Rheumatology. 2002;29(9):2024–2026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abud-Mendoza C, de la Fuente H, Cuevas-Orta E, Baranda L, Cruz-Rizo J, González-Amaro R. Therapy with statins in patients with refractory rheumatic diseases: a preliminary study. Lupus. 2003;12(8):607–611. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu429oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tikiz C, Utuk O, Pirildar T, et al. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and statin treatment on inflammatory markers and endothelial functions in patients with longterm rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Rheumatology. 2005;32(11):2095–2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Doornum S, McColl G, Wicks IP. Atorvastatin reduces arterial stiffness in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2004;63(12):1571–1575. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.018333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarey DW, McInnes IB, Madhok R, et al. Trial of Atorvastatin in Rheumatoid Arthritis (TARA): double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2004;363(9426):2015–2021. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16449-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charles-Schoeman C, Khanna D, Furst DE, et al. Effects of high-dose atorvastatin on antiinflammatory properties of high density lipoprotein in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study. Journal of Rheumatology. 2007;34(7):1459–1464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: executive summary. European Heart Journal. 2007;28(19):2375–2414. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]