Abstract

Background

The biologic mechanisms by which laparoscopic antireflux surgery (LARS) might influence the inflammatory process leading to bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome are unknown. We hypothesized that LARS alters the pulmonary immune profile in lung transplant patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Methods

In 8 lung transplant patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease, we quantified and compared the pulmonary leukocyte differential and the concentration of inflammatory mediators in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) 4 weeks before LARS, 4 weeks after LARS, and 12 months after lung transplantation. Freedom from bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (graded 1–3 according to the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines), forced expiratory volume in 1 second trends, and survival were also examined.

Results

At 4 weeks after LARS, the percentages of neutrophils and lymphocytes in the BALF were reduced (from 6.6% to 2.8%, P = 0.049, and from 10.4% to 2.4%, P = 0.163, respectively). The percentage of macrophages increased (from 74.8% to 94.6%, P = 0.077). Finally, the BALF concentration of myeloperoxide and interleukin-1β tended to decrease (from 2109 to 1033 U/mg, P = 0.063, and from 4.1 to 0 pg/mg protein, P = 0.031, respectively), and the concentrations of interleukin-13 and interferon-γ tended to increase (from 7.6 to 30.4 pg/mg protein, P = 0.078 and from 0 to 159.5 pg/mg protein, P = 0.031, respectively). These trends were typically similar at 12 months after transplantation. At a mean follow-up of 19.7 months, the survival rate was 75% and the freedom from bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome was 75%. Overall, the forced expiratory volume in 1 second remained stable during the first year after transplantation.

Conclusions

Our preliminary study has demonstrated that LARS can restore the physiologic balance of pulmonary leukocyte populations and that the BALF concentration of pro-inflammatory mediators is altered early after LARS. These results suggest that LARS could modulate the pulmonary inflammatory milieu in lung transplant patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux disease GERD, Laparoscopic antireflux surgery LARS, Lung transplantation, Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome BOS, Inflammation

1. Introduction

Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) after lung transplantation has been associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Several investigators have postulated that the association between GERD and BOS should be found in the susceptibility of lung transplant patients to aspirate gastro-esophageal contents, an event that has been thought to trigger a chronic inflammatory process in the lung allograft [1,2]. In support of this hypothesis, indirect evidence from several studies has shown that stopping aspiration with surgical control of GERD after lung transplantation can stabilize or improve lung function [3–5]. The results of our own studies have recently provided direct evidence that laparoscopic antireflux surgery (LARS) can prevent aspiration of gastro-esophageal refluxate and delay the onset of BOS in lung transplant patients [6]. Specifically, we have shown that LARS performed after lung transplantation can minimize aspiration of pepsin in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and that aspiration of pepsin is associated with a quicker progression to BOS and more acute rejection episodes [6]. Nevertheless, despite the progress in understanding the association between GERD and BOS and the protective role of LARS in the prevention of aspiration, we still lack a clear understanding of the biologic mechanisms by which LARS might influence the pro-inflammatory and fibrosing process leading to BOS. Recent data have shown that surgical control of GERD is associated with a significant reduction in the frequency of CD8-positive effector T cells in the BALF of lung transplant patients, thus indicating a mechanistic relationship between the control of GERD and the prevention of BOS [7]. In the present study, we hypothesized that LARS can alter the pulmonary immune profile in lung transplant patients with GERD. We aimed to elucidate how LARS can influence the biologic environment of the lung allograft by describing the immunologic changes that occur in the lung allograft before and after LARS. The rationale of the present study was to strengthen our understanding of the immune milieu of the lung allograft long before fibrosis occurs and to recognize the role that GERD has in eliciting a chronic immunologic fibrotic response. Ultimately, the goal of our investigations was to validate, in lung transplant patients, our attempts at controlling aspiration-induced GERD with LARS as a method to prevent chronic rejection, decrease the incidence of BOS, and improve survival.

2. Methods

From September 2009 to November 2011, 268 BALF samples were prospectively collected from 108 lung transplant patients. The patients were enrolled at surveillance bronchoscopy. Of the 108 lung transplant patients from whom BALF fluid was collected, 58 had undergone screening for GERD by esophageal function tests. Patients with GERD were then evaluated for LARS and their candidacy for the operation was determined by the results of ambulatory pH monitoring. The demographics, test results, including assessment of esophageal function, gastric emptying studies, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) data from pulmonary function tests, and data on BOS grade according to guidelines from the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation [8] were entered prospectively into a dedicated database.

In our cohort of 23 patients with GERD who underwent LARS, we identified 8 lung transplant patients from whom we had collected BALF samples 4 weeks before LARS and again 4 weeks after LARS and who had undergone LARS within 6 months of lung transplantation. The timing of BALF analysis was specified to match the occurrence of the surveillance biopsy and lavage, to standardize the interval since transplantation between patients and for comparison with a similar study by Neujahr et al. [7]. In these patients, we contrasted the pulmonary leukocyte differential, the BALF concentration of pulmonary immune mediators, and the BALF concentration of pepsin, before and after LARS. For 5 of 8 patients, these data were also available at 12 months after transplant and were included for comparison. The outcomes of these 8 patients were then reviewed in terms of freedom from BOS, FEV1 trends, and survival.

The Loyola University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (LU202400) approved the present study, and all study subjects provided informed consent.

2.1. Esophageal function testing, gastric emptying studies, and technique of fundoplication

Esophageal function testing was undertaken in lung transplant recipients, as we have previously described [9]. In brief, proton pump inhibitors were stopped for 14 days and histamine H2-receptor antagonists were stopped for 3 days before pH monitoring. An ambulatory 24-hour esophageal impedance pH catheter (Sleuth System with BioVIEW software; Sandhill Scientific, Denver, CO) was placed with the distal pH sensor positioned 5 cm from the manometrically determined upper border of the lower esophageal sphincter. The DeMeester score was calculated for the distal pH recordings and a score greater than 14.7 was considered diagnostic of GERD. Proximal reflux was defined as greater than 1% total time of pH less than 4 recorded at the proximal sensor, which was located 20 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter [9]. The detection of impedance reflux episodes was established according to reference ranges of normal volunteers as previously reported by Shay et al. [25].

Nuclear medicine gastric emptying studies were performed by obtaining dynamic scintigraphic images through the abdomen for 90 minutes after oral administration of 0.4 mCi technetium-99m–labeled sulfur colloid in ovalbumin. Gastric emptying was considered delayed if less than 30% of the gastric contents were emptied into the small bowel by 90 minutes [9].

LARS was performed as a 360° Nissen fundoplication in all patients, according to our standardized technique [10].

2.2. Technique of BALF collection and storage

In all patients, BALF was routinely collected from the right middle lobe for unilateral right and bilateral lung transplants and from the lingula for unilateral left lung transplants [6]. The BALF was then centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 minutes, separated into aliquots, and snap frozen at −80°C for analysis of pulmonary immune mediators [6].

2.3. BALF sample processing

The pulmonary immune mediators in BALF samples were measured by multiplex bead array (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as previously described by our own laboratories [11]. Similarly, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was undertaken to measure the BALF concentrations of neutrophil elastase (Cell Sciences, Canton, MA), transforming growth factor-β1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and pepsin, according to manufacturer’s instructions, and as previously described [26]. Finally, the concentration of myeloperoxidase in the BALF was measured with the O-dianisidine myeloperoxidase assay [12].

2.4. Pulmonary function testing

All lung transplant patients underwent serial pulmonary function testing according to the institutional protocol, with spirometry and flow volume assessments performed at each clinic appointment and with any significant change in respiratory symptoms. As such, this generated a schedule of post-transplant FEV1 documentation once per week for the first month, twice monthly for the next 2 months, then every third month, or more frequently depending on the clinical indication. Additionally, full pulmonary function testing with and without bronchodilators was performed 6 months after transplantation and annually thereafter. All FEV1 data consisted of pulmonary function assessment without bronchodilators.

3. Results

Our final cohort included 8 lung transplant patients with GERD who had BALF samples collected 4 weeks before LARS and again 4 weeks after LARS. For 5 of the 8 patients, the BALF samples were also collected at 12 months after transplantation. No patient had a complication resulting from LARS.

The demographics and characteristics of each patient, with a corresponding symbol specific to each patient for identification throughout the subsequent graphs, are listed in Table 1. Of the total cohort, 1 patient was female, 3 patients had cystic fibrosis, 2 patients had idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and 1 patient each had α1-antitrypsin deficiency, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and pneumoconiosis. Moreover, 5 patients underwent a single lung transplant, 2 patients underwent a bilateral lung transplant, and 1 patient underwent repeat transplantation. All patients were maintained with an immunosuppressive regimen with prednisone, a calcineurin inhibitor, and a cell cycle inhibitor.

Table 1.

Demographics of lung transplant patients who underwent LARS for GERD.

| Pt. No. | Symbol | Age (y) | Gender | Principal diagnosis | Transplant type | DeMeester score | Proximal reflux | DGE | LARS timing (mo) | Follow-up (mo) | BOS | Deceased |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

29 | Male | CF | Bilateral | 99.3 | Yes | No | 6 | 27 | No | No |

| 2 |

|

59 | Male | AATD | Right single | 25.9 | Yes | Yes | 3 | 15 | No | Yes |

| 3 |

|

51 | Male | IPF | Right single | 26.0 | Yes | Yes | 6 | 25 | Yes | No |

| 4 |

|

23 | Male | CF | Bilateral | 57.6 | Yes | Yes | 3 | 23 | Yes | Yes |

| 5 |

|

55 | Female | COPD | Left single | 36.6 | No | No | 6 | 21 | No | No |

| 6 |

|

64 | Male | PF | Left single | 35.6 | No | Yes | 3 | 16 | No | No |

| 7 |

|

34 | Male | CF | Bilateral | 22.1 | No | No | 3 | 15 | No | No |

| 8 |

|

61 | Male | IPF | Left single | 37.4 | Yes | No | 3 | 17 | No | No |

LARS = laparoscopic antireflux surgery; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease; Pt. No. = patient number; DGE = delayed gastric emptying; BOS = bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; CF = cystic fibrosis; AATD = α1-Antitrypsin-deficiency; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PF = pulmonary fibrosis from pneumoconiosis.

The analysis of the esophageal reflux profile showed a mean DeMeester score of 42.6 ± 25.4 and a 63% prevalence of proximal reflux before LARS. Additionally, 2 of 8 patients had evidence of non-acid reflux (patients 1 and 7). One half of the lung transplant patients with GERD had delayed gastric emptying before LARS, which was an average of 4.3 ± 1.7 months after transplantation. At a mean follow-up of 19.7 ± 4.8 months, the rates of survival and freedom from BOS were both 75%. Specifically, 1 patient (patient 3) developed grade 1 BOS 14 months after transplantation for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; this surviving patient received inhaled cyclosporine and received a baseline regimen consisting of prednisone, sirolimus, FK-506, and azithromycin with stabilization of lung function. Another patient (patient 4) developed grade 1 BOS at 20 months after lung transplantation for cystic fibrosis and died at 23 months after transplantation from complications arising from ventilator-associated pneumonia. An additional patient (patient 2) died of complications from high-grade Burkitt’s lymphoma at 14 months after transplantation for α1-antitrypsin deficiency, although this patient did not have BOS.

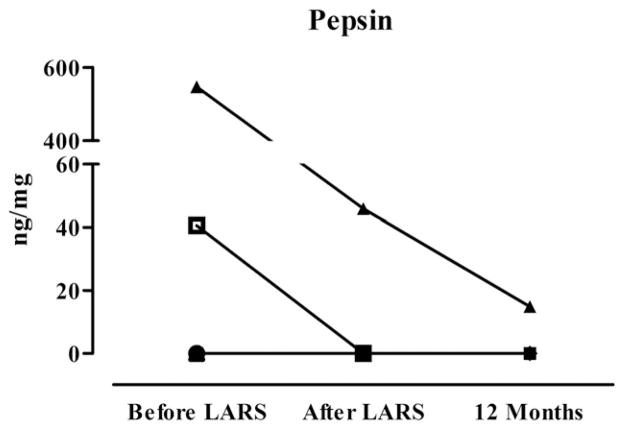

Fig. 1 demonstrates the BALF pepsin concentrations of the lung transplant patients before LARS, early after LARS, and 12 months after lung transplantation. Two patients (patients 3 and 7) had elevated pepsin levels in the BALF before LARS, which were in both cases reduced up to 12 months after lung transplantation. Additionally, patient 7 had evidence of non-acid reflux by impedance manometry. All other patients had undetectable levels of pepsin at all measurement points.

Fig. 1.

BALF concentrations of pepsin 4 weeks before LARS, 4 weeks after LARS, and 12 months after lung transplantation.

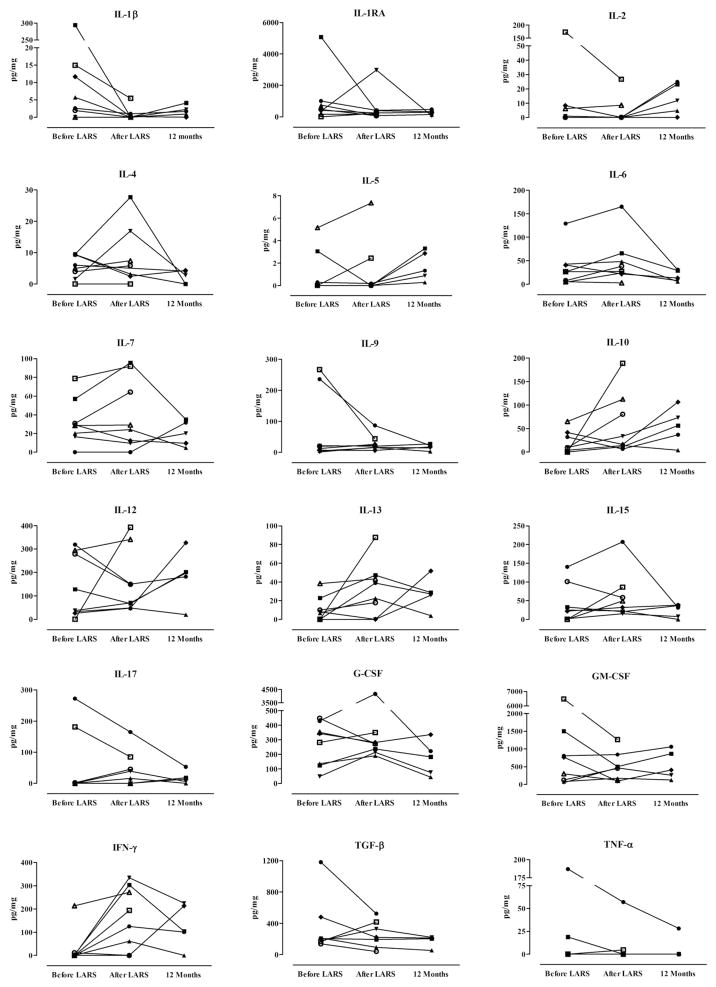

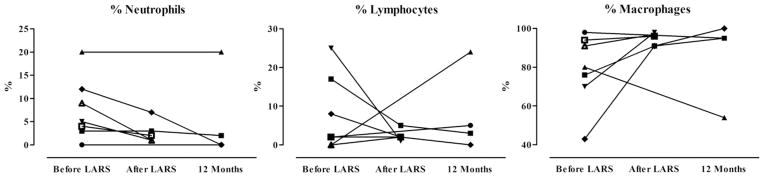

Fig. 2 shows the immunologic cellular profile of the BALF of lung transplant patients before and after LARS. Compared with the pre-LARS values, early after LARS, the percentage of the differential count of neutrophils decreased from 6.6% ± 3.8% to 2.8% ± 2.5% (P = 0.049), that of lymphocytes decreased from 10.4% ± 10.5% to 2.4% ± 1.5% (P = 0.163), and that of macrophages increased from 74.8% ± 20.4% to 94.6% ± 3.4% (P = 0.077). The outlying patient with a persistence of neutrophilia at 12 months after transplantation (patient 3) is 1 who had elevated pepsin concentrations before LARS and who also developed BOS. Otherwise, most patients had a relatively physiologic balance of pulmonary leukocytes 12 months after lung transplantation.

Fig. 2.

BALF differential in lung transplant patients 4 weeks before LARS, 4 weeks after LARS, and 12 months after lung transplantation. Data presented as the percentage of total leukocytes. Four weeks after LARS, the mean percentage of neutrophils was significantly lower than before LARS (P = 0.047), and differences in the percentage of lymphocytes and macrophages failed to reach statistical significance (P = 0.163 and P= 0.077, respectively). Analyses performed by paired t-test.

Fig. 3 demonstrates the concentrations of 18 BALF cytokines before and after LARS. Despite considerable variability between individuals and among cytokines, the concentration of interleukin (IL)-1β was significantly reduced early after LARS (from a median of 4.1 to a median of 0.0 pg/mg, P = 0.031), and the concentration of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) became significantly greater (median 0.0 pg/mg to 159.5 pg/mg; P = 0.031). Likewise, the concentration of IL-13 also increased early after LARS, although this difference failed to reach significance (median 7.6 pg/mg to 30.4 pg/mg; P = 0.078). Those patients who had elevated levels of several cytokines before LARS commonly had proximal reflux, non-acid reflux, and/or elevated pepsin concentrations in their BALF.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of bronchoalveolar lavage cytokines among lung transplant patients 4 weeks before LARS, 4 weeks after LARS, and 12 months after lung transplantation. At 4 weeks after LARS, the concentrations of IL-1β were lower, and those of IFN-γ were greater, than before LARS (P < 0.05). Analyses by Wilcoxon sign rank test.

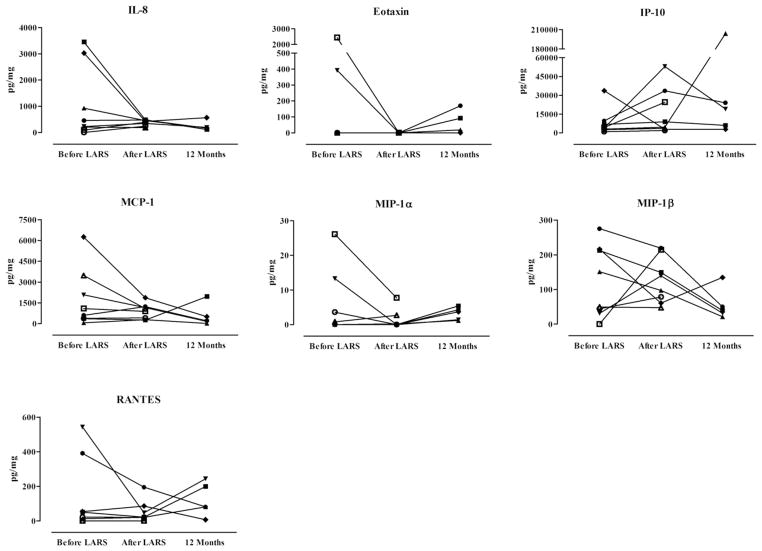

Fig. 4 shows the concentration of seven chemokines in the BALF before and after LARS. Although the concentrations of several chemokines appeared greatly reduced for certain individuals, the differences were not significant. In parallel to the increase of IFN-γ, the BALF concentrations of IFN-γ–induced protein 10 (IP-10) also appeared similarly increased (median 3959 pg/mg to 6735 pg/mg) early after LARS; however, no statistically significant difference was noted (P = 0.250), likely the effect of the 1 patient (patient 4) with an inverse trend, who later developed BOS. After excluding this patient, a difference was seen in the concentration of IP-10 early after LARS (P = 0.016). Also, the other patient who developed BOS (patient 3) had a considerable elevation of IP-10 at 12 months after transplantation. Finally, IL-8 remained reduced throughout the study period after LARS, and patients with non-acid reflux often had elevated BALF concentrations of several chemokines before LARS.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of bronchoalveolar lavage chemokines among lung transplant patients 4 weeks before LARS, 4 weeks after LARS, and 12 months after lung transplantation. Differences not significant. Analyses by Wilcoxon sign rank test. MCP-1 = monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MIP-1α = macrophage inflammatory protein-1α; MIP-1β = macrophage inflammatory protein-1β; RANTES = regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed, and secreted.

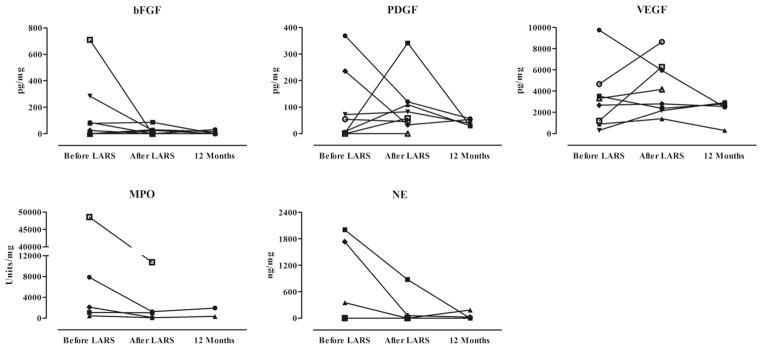

Fig. 5 demonstrates the BALF concentrations of 5 growth factors and markers of neutrophil activity. Although the median concentration of basic fibroblast growth factor was reduced from 52.2 pg/mg to 11.0 pg/mg, this difference failed to reach significance (P = 0.297). Likewise, and although just shy of significance, the concentration of myeloperoxidase was reduced from a median of 2109 U/mg to 1033 U/mg (P = 0.063) and remained reduced 12 months after lung transplantation. This finding supports the reduced percentage of neutrophils in the BALF leukocyte differential, as previously described, just as does the pattern of reduced concentrations of neutrophil elastase, although the interpretation of changing concentrations of this marker of neutrophil function were limited by a lack of sample availability and reduced patient number.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of bronchoalveolar lavage growth factors and markers of neutrophil activity in lung transplant patients 4 weeks before LARS, 4 weeks after LARS, and 12 months after lung transplantation. Four weeks after LARS, concentrations of myeloperoxidase (MPO) were lower, although just shy of statistical significance (P = 0.063). All other comparisons were not significant. Analyses by Wilcoxon sign rank test. bFGF = basic fibroblast growth factor; PDGF = platelet-derived growth factor; VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor; NE = neutrophil elastase.

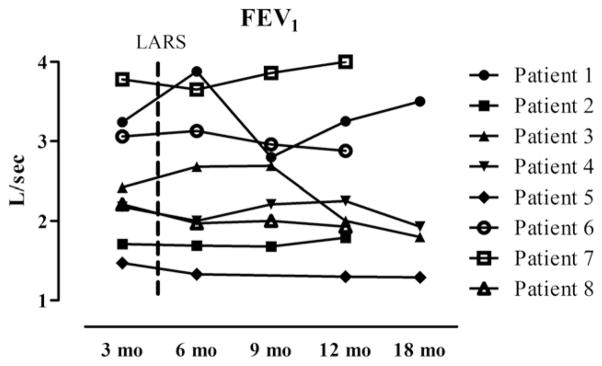

Finally, as represented in Fig. 6, after LARS, the FEV1 of the cohort remained stable, averaging 2.5 ± 0.8 L/1 s at 3 months, 2.5 ± 0.9 L/1 s at 6 months, 2.6 ± 0.7 L/1 s at 9 months, and 2.4 ± 0.9 L/1 s at 12 months after transplantation. Follow-up was available to 18 months for only 4 of the 8 patients.

Fig. 6.

FEV1 of lung transplant patients undergoing LARS. Dashed line indicates mean interval to LARS after lung transplantation. Patients 3 and 4 were diagnosed with BOS, stage 1, at 14 and 20 months, respectively.

4. Discussion

The high prevalence of GERD in patients with end-stage lung disease and after lung transplantation has been convincingly documented, and the promise of antireflux surgery in preserving lung function in those with GERD is increasingly gaining traction. A decade of research has validated these findings among lung transplant centers worldwide, which continue to be affirmed by even the most recent investigations [13,14]. Although the biologic mechanisms by which aspiration of gastroduodenal contents have been researched in both humans and animal models, the immune changes occurring after anti-reflux surgery that favor the preservation of lung transplant function are presently understudied. Our investigation of lung transplant recipients, which assessed the biologic effect of fundoplication on the allograft, has demonstrated that the normal pulmonary leukocyte differential appears restored after LARS, which seemingly coincides with a reduced pro-inflammatory environment. Nonetheless, some patients still progressed to early BOS development, suggesting that a pathologic process might have already been set in motion before LARS.

The balance and phenotype of pulmonary leukocytes after lung transplantation are influenced by many factors, including, but not limited to, ischemia/reperfusion, acute rejection, chronic rejection, immunosuppression, infection, and GERD/aspiration. Regarding the latter, evidence has linked the aspiration of gastroduodenal contents to several immunomodulating effects, such as alveolar neutrophilia [1,15,16], increased levels of the chemokine IL-8 [1,15], reduced levels of surfactant proteins SP-A and SP-D [17], augmented indirect allorecognition [18], and increased local levels of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor-α, and tumor necrosis factor-β [19]. These findings all support the central dogma for the development of BOS, which is a chronic process marked by recurring injury, remodeling, and repair that ultimately results in allograft failure typified by obliterative fibrosis. This provides a relatively clear theory for the detrimental effects of GERD-related aspiration on the pulmonary allograft and quite likely explains the preservation of lung function by fundoplication that is increasingly documented. Nonetheless, we are aware of only 1 study that has investigated the biologic changes induced by fundoplication in lung transplantation. In a cohort of 8 lung transplant patients undergoing gastric fundoplication, Neujahr et al. [7] found a post-fundoplicative reduction in the frequency of effector CD8-positive lymphocytes as measured in the BALF. These investigators speculated that GERD and aspiration might contribute to BOS through a repetitive injury process involving the recruitment of activated T-cells into the pulmonary allograft, thereby exacerbating the local inflammatory process caused by the aberrant presence of gastroduodenal contents. In concert with these findings, our study similarly supports the hypothesis that fundoplication might beneficially alter the pro-inflammatory and fibrosing environment induced by repetitive microaspiration. These results indicate a normalization of the pulmonary leukocyte differential in the BALF after LARS, marked by a reduction in the percentages of neutrophils and lymphocytes, along with a concurrent increase in the percentage of macrophages. Therefore, the aspiration-induced influx of neutrophils and lymphocytes, as previously suggested [1,7,15,16], appears to be mitigated by LARS. The reduced drive for leukocyte recruitment also appears to be reflected in the pattern of chemokines detected in the BALF, such that after LARS, and with the exception of IP-10, the concentrations of IL-8, eotaxin, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α, macrophage inflammatory protein-1β, and regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed, and secreted (RANTES) either remain constant or are reduced for most patients. These findings might be important because the upregulation of chemokines in the BALF have been linked to BOS [20]. Furthermore, a restoration of the physiologic balance to a macrophage-predominant population, along with a reduction of chemotactic protein concentrations, might indicate the resolution of clinical (or subclinical) acute cellular rejection and/or infection. Finally, these changes after LARS also appear to involve an improvement in the overall balance of pro-inflammatory mediators derived from the pulmonary allograft, specifically along the lines of IL-1β, which itself has been linked to aspiration-induced pulmonary inflammation [21].

The present study was intended as a preliminary investigation into the biologic effects of LARS in lung transplant patients; thus, several perspectives require consideration. First, a much greater sample size will be required to elucidate the true biologic effects, if any, that aspiration and fundoplication have on the lung transplant. This is particularly salient given the constantly changing immune environment of the pulmonary allograft related to differences in allorecognition, immunosuppression, infection (bacterial, viral, or fungal), and GERD/aspiration, all of which have been linked to chronic lung transplant rejection. Second, there must be a legitimately sized and appropriately selected control group of lung transplant patients with GERD who do not undergo LARS, with assessments of immune function undertaken at similar points after transplantation as the treatment group. Not only might this better highlight the immune changes induced by LARS, but it could help to identify the optimal timing of LARS after lung transplantation to maximize its therapeutic potential. We could not include such a control group in our analysis, because it is the protocol at our institution that lung transplant patients undergo LARS after being diagnosed with GERD, and the very few who do not either decline the operation or are unfit to undergo general anesthesia. Finally, and pursuant to that of the study by Neujahr et al. [7], studies should investigate the various phenotypes and functionality of the pulmonary immune cells in these individuals with flow cytometry, message assessment, and cell signaling analysis. Our data in particular, although overall consistent with a shift from a Th1/Th17 to Th2 milieu with a reduction in the composition of damaging cells and pro-inflammatory proteins, are unsupported by mechanistic studies. Such an approach might also lend greater clarity to the role of the macrophage after lung transplantation and explain why proteins that are related to macrophage functionality appear elevated after LARS in our study, such as IFN-γ and IP-10. This is particularly important as the cell profile in obliterative brochiolitis is characterized by a relative decrease in alveolar macrophages and alveolar macrophage surface markers in the setting of increasing neutrophilia and lymphocytosis [22,23] and that pulmonary leukocytes in some with obliterative brochiolitis might even be devoid of inflammatory activity (in other words, “burned out”) [24].

5. Conclusions

Despite technical advancements and improved immunomodulation strategies, outcomes after lung transplantation remain unfavorable. For some patients, elucidating the biologic effects of aspiration might uncover an avenue to improving freedom from BOS and lung transplant survival, if not simply to support routine testing for GERD and treatment with LARS, when safe and appropriate. The data presented in the present investigation, although preliminary, seem to imply an improved immunologic environment after LARS for GERD in these patients. Given the promise of fundoplication in lung transplantation, additional research should build from these early results and aim to discern the biologic mechanism behind the apparent link among GERD, aspiration, and BOS.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the pulmonologists, transplant coordinators, nurses, and respiratory therapists at Loyola University Chicago for their ongoing contributions, with which this study could not have been performed. This work has been supported by the Dr. Ralph and Marian C. Falk Medical Research Trust, by funding from Loyola University Chicago, and by funding from the 2011 SAGES Research Grant Award (PMF) for the study titled, “A non-invasive test to detect markers of aspiration after lung transplantation.”

Footnotes

Accepted for oral presentation at the 7th Academic Surgical Congress, February 14–16, 2012, Las Vegas, NV.

References

- 1.D’Ovidio F, Mura M, Tsang M, et al. Bile acid aspiration and the development of bronchiolitis obliterans after lung transplantation. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:1144. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hadjiliadis D, Davis RD, Steele MP, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in lung transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2003;17:363. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2003.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantu E, III, Appel JZ, III, Hartwig MG, et al. Maxwell Chamberlain Memorial Paper: Early fundoplication prevents chronic allograft dysfunction in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1142. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis RD, Jr, Lau CL, Eubanks S, et al. Improved lung allograft function after fundoplication in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease undergoing lung transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:533. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lau CL, Palmer SM, Howell DN, et al. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery in the lung transplant population. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1674. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisichella PM, Davis CS, Lundberg PW, et al. The protective role of laparoscopic antireflux surgery against aspiration of pepsin after lung transplantation. Surgery. 2011;150:598. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neujahr DC, Mohammed A, Ulukpo O, et al. Surgical correction of gastroesophageal reflux in lung transplant patients is associated with decreased effector CD8 cells in lung lavages: A case series. Chest. 2010;138:937. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estenne M, Maurer JR, Boehler A, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome 2001, an update of the diagnostic criteria. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002;21:297. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis CS, Shankaran V, Kovacs EJ, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease after lung transplantation: pathophysiology and implications for treatment. Surgery. 2010;148:737. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis CS, Jellish WS, Fisichella PM. Laparoscopic fundoplication with and without pyloroplasty for gastroesophageal reflux disease in the lung transplant population: How I do it. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1434. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1233-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis CS, Albright JM, Carter SR, et al. Early pulmonary immune hyporesponsiveness is associated with mortality after burn and smoke inhalation injury. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:26. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e318234d903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salter JW, Krieglstein CF, Issekutz AC, Granger DN. Platelets modulate ischemia/reperfusion-induced leukocyte recruitment in the mesenteric circulation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1432. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.6.G1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoppo T, Jarido V, Pennathur A, et al. Antireflux surgery preserves lung function in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and end-stage lung disease before and after lung transplantation. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1041. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartwig MG, Anderson DJ, Onaitis MW, et al. Fundoplication after lung transplantation prevents the allograft dysfunction associated with reflux. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:462. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vos R, Blondeau K, Vanaudenaerde BM, et al. Airway colonization and gastric aspiration after lung transplantation: Do birds of a feather flock together? J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:843. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reynaud-Gaubert M, Thomas P, Gregoire R, et al. Clinical utility of bronchoalveolar lavage cell phenotype analyses in the postoperative monitoring of lung transplant recipients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21:60. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)01068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Ovidio F, Mura M, Ridsdale R, et al. The effect of reflux and bile acid aspiration on the lung allograft and its surfactant and innate immunity molecules SP-A and SP-D. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1930. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meltzer AJ, Weiss MJ, Veillette GR, et al. Repetitive gastric aspiration leads to augmented indirect allorecognition after lung transplantation in miniature swine. Transplantation. 2008;86:1824. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318190afe6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li B, Hartwig MG, Appel JZ, et al. Chronic aspiration of gastric fluid induces the development of obliterative bronchiolitis in rat lung transplants. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:1614. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynaud-Gaubert M, Marin V, Thirion X, et al. Upregulation of chemokines in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid as a predictive marker of post-transplant airway obliteration. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2002;21:721. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00392-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Appel JZ, III, Lee SM, Hartwig MG, et al. Characterization of the innate immune response to chronic aspiration in a novel rodent model. Respir Res. 2007;8:87. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magnan A, Mege JL, Reynaud M, et al. Monitoring of alveolar macrophage production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 in lung transplant recipients. Marseille and Montreal Lung Transplantation Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:684. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.3.8087338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward C, Whitford H, Snell G, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage macrophage and lymphocyte phenotypes in lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20:1064. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(01)00319-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tiroke AH, Bewig B, Haverich A. Bronchoalveolar lavage in lung transplantation: State of the art. Clin Transplant. 1999;13:131. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.130201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shay S, Tutuian R, Sifrim D, et al. Twenty-four hour ambulatory simultaneous impedance and pH monitoring: a multicenter report of normal values from 60 healthy volunteers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisichella PM, Davis CS, Lundberg PW, et al. The protective role of laparoscopic antireflux surgery against aspiration of pepsin after lung transplantation. Surgery. 2011;150:598. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]