Abstract

The following series of concise summaries addresses the evolution of infectious agents in relation to sex in animals and humans from the perspective of three specific questions: (1) what have we learned about the likely origin and phylogeny, up to the establishment of the infectious agent in the genital econiche, including the relative frequency of its sexual transmission; (2) what further research is needed to provide additional knowledge on some of these evolutionary aspects; and (3) what evolutionary considerations might aid in providing novel approaches to the more practical clinical and public health issues facing us currently and in the future?

Keywords: evolution, infectious agents, sexual transmission, econiche

Animal agents

Lice as both troublesome parasites and informative markers of host evolutionary history

David L. Reed

dlreed@ufl.edu

At present there are approximately 3,000 described species of lice.1,2 There is conflicting evidence surrounding the monophyly of the Order Phthiraptera. Recent molecular data suggests that lice are paraphyletic with the Psocoptera (book and bark lice), which would mean that obligate parasitism of birds and mammals evolved more than once within what is now known as Phthiraptera.3 Morphological evidence suggests that the Order Phthiraptera is a monophyletic group, but opponents contend that the characters that unite them are merely convergent, owing to the constraints of an obligate parasitic lifestyle. Within the Phthiraptera resides the Suborder Anoplura, which contains the obligate blood feeding lice of mammals. This clade of approximately 530 species is monophyletic based on morphological and molecular data. Within the Anoplura are the species of lice that infest humans, which are of interest here.

There are three types of lice that infest humans, clothing lice, head lice, and pubic lice. Clothing lice (also called body lice) and head lice are two morphotypes of a single species, Pediculus humanus.4 Head and clothing lice are modestly distinct in terms of their morphology, but have pronounced differences in their feeding behavior, egg deposition, and their ability to transmit disease.5 Clothing lice feed only a few times per day, lay eggs in clothing, and transmit three deadly microbial pathogens, whereas head lice feed frequently throughout the day, attach eggs to individual hair shafts, and are not known to transmit disease to human hosts in natural environments. Humans are also infested with the pubic louse (Pthirus pubis), which is the family Pthiridae. Humans likely acquired this parasite from a gorilla-like ancestor about three million years ago.6 Pubic lice are morphologically very different from clothing and head lice, and the two genera (Pthirus and Pediculus) have not shared a common ancestor for 13 million years.6 Pubic lice are unique among human lice in that they are primarily transmitted sexually. The presence of pubic lice is correlated with the presence of other sexually transmitted infections, but the lice themselves are not known to be vectors of sexually transmitted diseases.

The evolutionary events that led pubic lice to their current ecological niche are only partially known. Reed et al. showed that the evolutionary origins of pubic lice can be traced to a gorilla-associated ancestor, but the conditions under which that might have happened are speculative.6 The successful establishment of Pthirus on hominid hosts is interesting because hominids already played host to lice in the genus Pediculus when Pthirus invaded three million years ago. It is possible that humans had already lost much of their body hair, which caused lice of the genus Pediculus to retreat to head hair, leaving the pubic niche available for colonization. However, this also presumes that humans had already developed pubic hair, which is absent in other great apes, and develops at sexual maturity. The evolutionary loss of body hair, the development of pubic hair, and the later development of clothing in humans are watershed events in the evolutionary history of lice, and likely spawned the birth of new louse lineages.

Although pubic lice are estimated to infest about 2% of the world’s population, the exact number is exceedingly hard to quantify. Infestations are easy to acquire and sometimes difficult to eradicate. Permethrin-based products are often used to treat phthiriasis; and unlike head lice, pubic lice do not appear to be widely resistant to its use. The prevalence of pubic lice is declining in certain developed countries among men and women that remove their pubic hair.7

The lice of the genus Pediculus have provided great insight into primate and human evolutionary history—they have told us that humans began wearing clothing 170,000 years ago, prior to leaving Africa,8 and that modern humans had direct physical contact with archaic hominids perhaps around 25,000 years ago.9 Because pubic lice also parasitized humans during this time they represent ecological replicates of Pediculus that can be used to test the predictions gleaned from Pediculus about human evolution.

Furthermore, because Pthirus is a sexually transmitted parasite, its coevolutionary history with humans may differ from that of the more casually transmitted lice of the genus Pediculus. For example, there is strong evidence that head lice from Neanderthals made it onto modern humans, where traces of this host switch can still be seen in louse DNA. Reed et al. (2004) concluded that the host switch from Neanderthals to modern humans must have been caused by direct physical contact between the two species of host.9 If the pubic lice of living humans also show traces of Neanderthal louse DNA, then we might propose that interbreeding occurred supporting the findings of recent genome studies hinting at introgression between modern and archaic hominins.

We now have a complete genome of the human clothing louse (Pediculus humanus), which will facilitate much new research in the treatment of pediculosis and in studies of human/louse evolution. Similar efforts are needed to sequence the genome of the pubic louse to better understand its similarities and differences to Pediculus. The genome of Pediculus was incredibly small, owing to the reduced and simple environment that the louse lives within. A comparison to another louse living in roughly the same environment would be very useful. Whether the two different types of lice have similar gene composition will help us to understand how the external environment shapes genome evolution.

The treatment of pediculosis is a billion dollar industry, and new treatments are constantly being sought. Now that louse populations are resistant to insecticidal shampoos in most developed countries, new “evolution proof” ways of dealing with lice are being investigated. One such method uses hot air to kill lice and their eggs with no discomfort to the patient.10 It is likely that resistance to hot air would be difficult to evolve in louse populations. Similar “evolution-proof” treatments are not required for pubic lice, as this species has not yet evolved widespread resistance to the insecticides used to treat them.

Scabies in animals and humans

Russell W. Currier and Shelley F. Walton

ruscurrier@yahoo.com

Scabies is one of the great epidemic diseases of man. Not only are humans affected by the common itch mite Sarcoptes scabiei, but also numerous species of animals. Host species are infested with different variants of the same genus and species of mite, as is true in a number of other animal hosts—reflecting the overall observation that ectoparasites tend to be very host specific. Sarcoptic mange in animals and infestations in humans date back to antiquity, with some historians noting that Aristotle described these as lice-like creatures of the skin. However, most historians credit Avenzoar, the Moorish physician, and his student Averroes of Seville in the 12th century, with accurately describing the mites. Successive discoveries and descriptions were detailed by St. Hildegarde (12th century), August Hauptmann in 1654, and Giovanni Bonomo in 1687, who described and drew the mite.11 The Swedish physician and botanist Carolus Linnaeus established the parasitic nature of scabies in 1746, but eleven years later confused the mite with the common flour mite.12 These developments, however, were ignored and forgotten in the field of medicine. Finally a senior medical student in Paris, France, Simon Francois Renucci, extracted a mite from a female patient in August, 1834 with a needle probe—a technique he learned from peasant women in his native Corsica—to usher in the modern era of scabies diagnosis. This “rediscovery” was expanded in subsequent decades by Ferdinand von Hebra, the father of modern dermatology in Vienna, who established our basic knowledge of scabies.13

Scabies mites are transmitted by skin-to-skin con-tact, including sexual contact; after varying periods of time, usually three to six weeks, hypersensitivity develops to metabolites and secretions of the mites that result in pruritis, especially in the evening, and prompts patients to seek treatment. Diagnosis can be determined most commonly by skin scrapings examined microscopically with mineral oil (author RWC prefers microscopic immersion oil). Observing adult and larval mites, eggs, and scybala (discrete golden brown fecal pellets) are confirmatory. Since most otherwise healthy patients have fewer than 15 adult mites, it is important to collect sufficient scrapings to ensure a reasonable chance of recovering a mite. A slightly less traumatic and very specific method to identify scabies is needle extraction with the aid of a loupe or hand lens.14

Affected patients should be treated, and a variety of products are available including topicals: Lindane lotion, 5% permethrin lotion, crotamiton lotion or cream, and 6–10% precipitated sulfur in petrolatum. For the past 10 years, oral administration of ivermectin has produced good results, especially with a heavy mite burden, that is, patients profoundly immunosuppressed and for patients with “crusted” or keratotic scabies. In the UK and Commonwealth, benzyl benzoate preparations are licensed for treatment of scabies as well.15,16 Prophylactic treatment of close physical contacts, for example, family members, romantic acquaintances, and preschool siblings who are not yet exhibiting signs/symptoms should be considered on a case by case basis.

How did humans become colonized with S. scabiei? The scientific consensus is that humans, and protohumans before them, were the principal hosts for Sarcoptes mites.11,13 When humans domesticated various species of animals over the past 10,000 years, Sarcoptes mites jumped species and established new colonizations among recently domesticated animals. These species were more susceptible, likely because domestication per se tended to reduce immunocompetence and, thus, increased the probability of mites adapting to new hosts.17–19 Domesticated animals that escaped, in turn, infected several wild nondomesticated species.

Transmission of Sarcoptes in both humans and animals is by direct contact in most situations, but indirect contact may serve a role depending on crowding and individual host mite populations. In modern humans, sexual transmission is important especially among sexually active young people, who may further transmit the mite during care of young children. Scabies is, or should be, routinely considered in the framework of screening patients at risk for other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In evolutionary terms, humans may have become partially protected through the advent of clothing, with social trends towards monogamous relationships also reducing risk of exposure.

Walton et al.20,21 have demonstrated that canine and human scabies are phylogenetically distinct variants of S. scabiei with minimal gene exchange. (Heretofore there have been no definitive means to distinguish taxonomically the various strains that manifest a fairly high degree of host specificity for their respective host species.) As such, even if humans are infested, as well as their dogs, it would not require elaborate coordinated efforts to treat both groups simultaneously. Interestingly, these evolutionary studies in aboriginal indigenous communities in northern Australia with endemic scabies have led to changes in health policies at the regional level, with the development of cost effective public health intervention programs that are directed at humans only.20

Future research would best be directed at defining parasitic secretions and hidden antigens and their role in stimulating and modulating host immune responses. Better definition of S. scabiei gene families and their products will provide better insights into the molecular biology and host immune evasion strategies of the mite. Clearly, one of the major difficulties of managing scabies infestations in humans, as well as in animals, is recognizing infested hosts. An immunological test for diagnosis based on mite proteins would be most welcome.20

Another issue is the evidence for an inverse relation between parasites and allergy, as noted by Walton et al., observing that asthma and hay fever are rare in parts of the world where the population is heavily parasitized.21 “The relationship between susceptibility to, and severity of, symptoms with scabies and asthma are as yet unknown and conceivably may be interdependent. Those who suffer from house dust mite (HDM) allergy may have reduced (or possibly increased) symptoms of scabies and presumably the reverse—thosewith scabies could have a reduced (or increased) susceptibility to (HDM) antigens.”21

Investigating the evolutionary relationship of house dust and scabies mites, as well as their cross-antigenicity, may lead to improved diagnostics for both scabies and HDM allergy and potentially protective immunoprophylaxis for asthma.

Trichomonas infections of humans and animals

Melissa Conrad, Steven A. Sullivan, and Jane M. Carlton

Melissa.Conrad@nyumc.org

Trichomonads are protozoa of the class Parabasalia that inhabit the alimentary canals or urogenital tracts of vertebrates and insects. Members are characterized by having three to five anterior flagella, and many species have highly diverged mitochondrion-like organelles called hydrogenosomes. Trichomonads inhabit vertebrate hosts ranging from reptiles and amphibians to pigs and humans. Most are considered commensal, but even these can cause diarrhea and abdominal pain, as is the case for Pentatrichomonas hominis, a commensal found in the gastrointestinal tracts of several mammals. Three species of trichomonads are generally recognized as pathogens: Trichomonas gallinae, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Tritrichomonas foetus. T. gallinae is a parasite of the upper alimentary tracts of bird species and can cause severe necrotic ingluvitis. The remaining two species are sexually transmitted parasites that reside in the urogenital tracts of humans and cattle, respectively.

T.vaginalis is the causative agent of trichomoniasis, the most prevalent nonviral sexually transmitted disease in humans (reviewed in Ref. 22). The parasite adheres to the lining of the urogenital tracts of both men and women and can result in reproductive health sequelae, including pelvic inflammatory disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes, and has been associated with an increased risk in HIV transmission. About half of infected women manifest symptoms, including a frothy vaginal discharge, odor, itching, and punctate microhemorrhages on the cervix known as “strawberry cervix.” Men generally remain asymptomatic. T. foetus causes bovine trichomoniasis. Comparable to T. vaginais, T. foetus inhabits the reproductive tract and typically causes few symptoms in bulls, while cows frequently suffer from urogenital inflammation. Bovine trichomoniasis can also lead to severe consequences, such as infertility and abortion. Both T. vaginais and T. foetus appear to have a simple life cycle consisting of a trophozoite stage and a putative pseudocyst stage, and both divide asexually through mitosis.

With these similarities in mind, it is tempting to speculate that trichomoniasis is shared between cows and humans. However, phylogenetic analyses using genetic markers (SSU rRNA, GAPDH, enolase, (β-tubulin, α-tubulin, and Rpb1), and several morphological distinctions indicate that exploitation of the urogenital niche by the two species is the result of convergent evolution. T. vaginais and T. foetus are not sister taxa, being separated on a phylogenetic tree by many species that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract.23 In addition, they are morphologically distinct; T. vaginalis is characterized by four flagella, while T. foetus only has three. Both Trichomonas and Tritrichomonas are genera composed of a large number of gastrointestinal Parabasalids, suggesting that T. vaginais and T. foetus share a common gastrointestinal ancestor but evolved independently to colonize the urogenital niche. Indeed, T. foetus has been isolated from the feces of cats and dogs with diarrhea, suggesting that the parasite retains ancestral characteristics that allow it to continue to colonize and survive in the intestine.24

Instances of inferred convergent evolution provide an opportunity to compare derived similarities, in order to identify common traits that coincide with the shared niche. In the case of T. vaginais and T. foetus, we may be able to learn what characteristics provided these two trichomonad species with the appropriate “fitness” to transition from the gastrointestinal tract (the ancestral state) to the urogenital tract. Genomics will be a powerful tool in determining this evolutionary history.

The T. vaginalis genome was published in 2007.25 At 160 Mb, it is one of the largest parasite genomes known, dwarfing those of Entamoeba (20 Mb), Plasmodium (25 Mb), and Toxopasma (63 Mb). The large genome is thought to be the result of a sudden expansion of “repeats” that occurred after T. vaginalis and Trichomonas tenax, its sister taxon, split from their most recent common ancestor. At least 65% of T. vaginalis DNA consists of hundreds of families of transposable elements and multigene families that have undergone massive amplification. These gene expansions may have occurred after some evolutionary event, such as the reduction in effective population size,26 which could have followed the transition of the parasite from an enteric to a urogenital environment. However, a drastic increase in genome size over a short period of evolutionary time is typically detrimental,27 making it unlikely that such a trait would have been fixed by genetic drift alone; rather, it must have provided some selective advantage to the organism in its new environment.28 One possible selective advantage relates to the positive correlation between genome size and cell volume in trichomonads.29 An increase in cell volume, resulting from the increase in genome size due to fixation of expanded gene families, could have resulted in the parasite being able to augment phagocytosis of bacteria, reduce its vulnerability to phagocytosis by macrophages, and increase its cell surface to allow better adhesion to the vaginal mucosa. These advantages may have allowed T. vaginalis to thrive in its new vaginal environment.

One way to test this hypothesis would be to look for similar evolutionary tendencies in the T. foetus genome. It has been suggested that gene family expansions are common among Parabasalids,30 which we have confirmed through Roche 454 sequencing of the T. foetus and P. hominis genomes (unpublished). The genomes of these species are composed of a minimum of 28% and 20% “repeats,” respectively. Consistent with the difference in percentage of genome repeats, T. foetus has a 166–188 Mb genome (comparable to that of T. vaginalis ), while the P. ho-minis genome is 86–102 Mb.29 Perhaps here, too, a sudden expansion of gene families has contributed to a larger cell volume, which may have provided T. foetus with the necessary characteristics to diverge from its enteric ancestors and successfully colonize the bovine urogenital system.

Admittedly, our hypothesis is far from being proven. Unfortunately, there is also a lack of sufficient data to disprove it. If we ever hope to understand the mechanism by which trichomonads successfully moved from an enteric environment to the urogenital tract, it will be necessary to expand the inventory of whole genomes available from diverse Parabasalid species. Among the top priorities should be gastrointestinal species closely related to T. vaginalis and T. foetus , such as Dientamoeba fragilis and Trichomonastenax. Only by elucidating the state of ancestral genomes will we be able to determine how these species have evolved to adapt to new environments, and ultimately cause sexually transmitted diseases of significant veterinary and public health importance.

Chlamydia animal sexually transmitted infections

Timothy D. Read

tread@emory.edu

The Chlamydiaceae are an ancient group of Gram-negative obligate intracellular pathogens, currently divided into two genera, Chlamydia and Chlamydophila. All Chlamydiaceae share a distinctive biphasic lifecycle, alternating between a dormant infectious elementary body (EB) and a cell-bound vegetative reticulate body (RB). Complete sequencing projects of bacteria representing seven species have revealed relatively small genomes (1.1–1.2 Mb) with about 90% of genes conserved within the genus. Despite their limited genetic repertoire, Chlamydiaceae causea very diverse array of diseases in a broad range of hosts. These infections include sexually transmitted infections (STIs), pneumonia, abortions, gastritis, and sepsis. The range of hosts includes mollusks, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. Genomic studies have revealed ongoing adaptive evolution in the Chlamydiaceae, including acquisition of genes by Horizontal Gene Transmission (HGT) and frequent gene conversion.31 We know from evolutionary reconstructions that Chlamydiaceae can make dramatic host and disease shifts. The common human STI, Chlamydia trachomatis, is very similar to strains causing trachoma,32 and genomic evidence from koala-infecting strains indicate that the common human respiratory pathogen Chlamydia pneumoniae evolved from a zoonotic ancestor.33

Interest has been particularly focused on Chlamydiaceae in economically important animals, including C.abortus and C.pecorum in cattle, sheep, and/or goats, and mixed infections are also of interest.33–37 In the wild, Australian koalas have been found to be infected by C. pneumoniae and C. pecorum— the latter being the more pathogenic of the two, causing urogenital and ocular infections, and occasional outbreaks.38

There are two fundamental questions about Chlamydiaceae evolution that we are some way from answering: how do Chlamydia adapt to new host species, and how do Chlamydiaceae evolve new modalities of infection.

Genome sequencing is an increasingly cost-effective way to investigate these questions, and it will be soon possible to sequence thousands of Chlamydiaceae strains per week. We will soon be limited by well-sourced isolates. The well-maintained existing collections of Chlamydiaceae need to be made available for sequencing, and a major effort to acquire new, diverse strains from animals and the environment needs to be undertaken. Epidemiologic models for natural chlamydial sexually transmitted infection in wild animal species, for example, koalas and perhaps primates, may be useful to parallel information about these infections in humans.

Several recent examples, e.g., HIV, serve to warn us of the importance of tracking emerging zoonoses. Comparing the genomes of human- and non-human–infecting Chlamydiaceae on a large scale may allow us to define the genes acquired by HGT, or even genetic variants in core genes (single nucleotide polymorphisms, insertions, deletions, and inversion) that are associated specifically with human infection. This may lead us to better understand the traits that make a zoonotic pathogen more likely to cross over to infecting humans [e.g., Refs. 31 and 32]. Comparative genome analysis also provides information about epitopes on surface and secreted proteins that may be evolutionary constrained and hence viable targets for vaccine or immunologically targeted therapies. In the same vein, comparative genomics can help improve selecting targets for genetic- and immunologic-based diagnostics and inform where diagnostics are likely to fail.

Comparative sequencing will warn of the dangerous possibility for acquisition of antibiotic resistance genes into human Chlamydia STIs from animal-infecting strains. A recent paper described the uptake via HGT of a tetracycline resistance cassette into the genome of a pig pathogen—C. suis— that probably originated from Enterococcus.39 As we learn more about the pathways for gene exchange in Chlamydiaceae, we could anticipate the potential for losing drug efficacy for human infections based on patterns emerging in animal strains. Also, the possible effectiveness of a C. pecorum vaccine for animals, now in development,40 may provide a model for human chlamydia vaccines, providing information of their possible epidemiological and evolutionary impact.

Molecular evolution of human and simian simplexviruses

Alberto Severini, Shaun Tyler, and R. Eberle

alberto.severini@phac-aspc.gc.ca

Simplexviruses (or α-1 herpesviruses) belong to a genus within the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae comprising closely related viruses that have mostly primates as natural hosts. Bovine herpesvirus 2, however, infects cattle, and the poorly characterized macropodid herpesviruses 1 and 2 have been isolated from species of wallaby, a marsupial.41 Well characterized simplexviruses of primates are the human HSV-1 and HSV-2, B virus in Asian macaques, SA8 in vervets, herpesvirus papio 2 (HVP2) in African baboons, herpesvirus saimiri 1 (HVS) in squirrel monkeys, and the herpesvirus ateles 1 (HVA1) in spider monkeys.

Phylogenetic analyses based on nucleotide and amino acid sequencing have shown that simplexviruses from humans, old world monkeys, and new world monkeys each cluster in separate branches, indicating that, in general, they coevolved with their hosts.42,43 Despite the relative diversity of natural hosts, primate simplexviruses cause remarkably similar clinical manifestations, that is, orogenital vesicular lesions closely resembling HSV infections in humans including a generally benign course, establishment of latency with the possibility of reactivation, and occasionally severe neurological or other disseminated infections in newborns.44 Thus coevolution spanning about 50 million years seem to have preserved intact the sexual/oral tropism of this group of simplexviruses. However, infections of other primate species other than the natural host often results in more severe pathology, such as deadly B virus encephalomyelitis in humans44 or disseminated HSV infections in some non-human primate species.45,46

Complete genome sequencing of HSV-1,47–49 HSV-2,50 B virus,51 HVP2,52 SA8,53 and chimpanzee herpesvirus (ChHV; manuscript in preparation) has shown that their genomes are overall highly homologous (from 60% to 90% at the DNA evel) and almost all genes and features are collinear. Finer comparison of these genomes leads to the formulation of some hypothesis on the mechanisms of simplexvirus evolution and pathogenesis. Old World monkey simplexviruses (B virus, HVP2, and SA8) lack a homolog of the HSV RL1 open reading frame, the product of which (the γ1 34.5 protein) inhibits the cell interferon-activated, PKR-dependent system that shuts down protein synthesis in response to viral infection.54 As this is considered to be a factor of virulence in mice and humans for HSV, it will be interesting to study how Old World monkey simplexviruses circumvent the PKR system to infect their hosts and to cause severe diseases in humans (B virus) and mice (B virus and HVP2).

Another interesting comparison is the glycoprotein G (gG). This envelope glycoprotein is involved in virus entry in polarized cells and it is the only antigen that differs substantially between HSV-1 and HSV-2, and therefore it has been used for HSV type-specific serological assays.55 HSV-2 gG is a 699 amino acid protein which is cleaved roughly in half into a secreted amino terminus fragment and a transmembrane portion (mgG2) that is incorporated into the viral envelope.56 In contrast, the HSV-1 gG consists only of a 238 amino acid transmembrane protein homologous to mgG2. All of the other Old World simian simplexviruses and, surprisingly, bovine herpesvirus 2, possess an HSV-2-like glycoprotein gene. In contrast, the New World virus HVS1 has a putative gG gene that is similar in structure (but not in sequence) to the HSV-1 gG.

We have recently sequenced the entire genome of chimpanzee herpesvirus, a simplexvirus isolated from a captive animal with oral lesions.57 The genome sequence is remarkably similar to that of HSV-2 (almost 90% homology at the DNA level), but still distinct enough from all known variants of HSV-2 to be considered a distinct virus. The level of DNA sequence divergence is consistent with the human/chimpanzee divergence estimated to have occurred 4 to 6 million years ago.57 The more divergent HSV-1 was estimated to have separated from HSV-2 about 8–9 million years ago,58 and, if these estimates are correct, we have to consider the possibility that HSV-1 did not coevolve with the human species, but rather that its progenitor “colonized” us at a later time in evolution, jumping from an as yet unidentified primate host. Interestingly the aforementioned RL1 virulence gene is the only gene that is most similar between HSV-1 and HSV-2. A comparison of the mechanism of the virulence of the RL1 genes of HVS-1, HSV-2, and ChHV may shed light on the species tropism of these viruses.

The recent whole genome sequence of HSV-1 has confirmed the more distant relationship between New World monkey simplexviruses and the Old World monkey simplexviruses.59 Most HSV-1 genes are homologous to those of other simian simplexviruses, but their arrangement and the overall structure of the genome is similar to that of VZV, α varicellovirus. We can hypothesize that HSV-1 is closer to the common progenitor of all α-herpesviruses, a hypothesis that may be tested by sequencing other α-herpesviruses and by comparative analysis of the function of their gene products.

Whole genome analysis of simplexviruses is a powerful tool aiding in understanding the evolution of this genus in relation to their hosts and to other groups of herpesviruses. Comparative analysis in vitro and in animal models of the function of the few divergent genes may provide insight on the pathogenesis mechanisms of HSV-1 and HSV-2 in humans. All of the primate simplexviruses produce in their natural hosts the same, generally benign, often recurrent vesicular disease and are transmitted by oral or genital contact. Yet, their virulence differs dramatically when these same viruses are transmitted to other host species. A comparative analysis of the virus/natural host interaction maybe a good approach in defining the still elusive pathogenic mechanisms of HSV and the evolution of herpesvirus sexual transmission.

Primate lentiviruses and their hosts

Welkin E. Johnson and Guido Silvestri

welkin_johnson@hms.harvard.edu

The primate lentiviruses include the human pathogens, HIV-1 andHIV-2, and the closely related simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs), which are endemic among many species of African apes and monkeys.60,62 The phylogenetic relationships among the primate lentiviruses do not consistently mirror host phylogeny, an indication that the distribution of SIVs among modern primates is the result of numerous cross-species jumps followed by adaptation and emergence of new host–virus combinations (the relatively recent emergence of HIV-1 and HIV-2 in humans being notable examples). In addition to extant SIVs, which have been detected in more than 40 species of African primate, ancient SIV-like proviral sequences have been found embedded in the genomes of lemurs.61 These defective relics of an ancient ancestor of the modern SIVs are direct evidence that lentiviruses were already present in ancestral primate populations millions of years ago.

A distinctive trait of all primate lentiviruses is their capacity for replication in the face of what is, at least initially, a robust virus-specific immune response.63 Infections are characterized by continuous, uninterrupted viral replication and rapid turnover of the virus population. A consequence of high-titer virion production is killing of CD4+ T cells, a central player in the adaptive immune response. The capacity to generate and maintain very large population sizes within the infected individual (coupled with an error-prone viral polymerase) permits these viruses to adapt rapidly to the slightest shifts in selective pressure, including the onset of virus-specific immune responses in a newly infected individual and changes in genetic landscape encountered when jumping between individuals or populations of individuals.

Among many primate species harboring endemic SIVs, there is a notable absence of pathogenesis. Most intriguing to AIDS researchers, the non-pathogenic condition does not correlate with fundamental differences in virulence.64 For example, viral replication kinetics and T cell killing are strikingly similar in natural hosts of SIVs, where pathogenesis is the exception, and in animal models of AIDS (e.g., the SIV-infected rhesus macaque) or humans with HIV, in which pathogenesis is the rule. The lack of pathogenic outcome in many natural hosts of SIVs is viewed as a strong indication that these particular virus–host relationships are the result of long periods of coevolution, possibly spanning hundreds or thousands of host generations. Nonpathogenic infection, which may have evolved independently on multiple occasions, suggests that these natural hosts represent genetic “uncoupling” of overt pathogenesis from viral replication.

While the major focus of HIV/AIDS research is on humans, comparative approaches encompassing the primate lentiviruses and their hosts as a whole are desirable. In particular, two areas deserve closer examination of SIV infections in natural hosts.

Why does infection with HIV result in AIDS?

Identifying the specific adaptive mechanism(s) by which the natural hosts of SIVs uncouple pathogenesis from viremia may suggest previously unimagined avenues for treatment of patients with established HIV infection and should be the target of more intensive research efforts. Toward the same end, efforts to identify and investigate rare cases of HIV-infected individuals with evidence of long-term high-level viremia but notable absence of disease should also be pursued.

How do host genes influence cross-species transmission and emergence of viral pathogens?

Given the close evolutionary relationships between humans and other primates, a key question in virology is whether viruses of other primates are more likely to spread and adapt in human populations than viruses from more distantly related species (anecdotally, the worldwide spread of HIV-1, the result of transmission of SIVcpz from chimpanzees to humans, compared to the more limited success of HIV-2, which arose by transmission of SIVsm from sooty mangabey monkeys, is consistent with this notion). Along these lines, comparative studies of humans and nonhuman primates and their respective viruses could prove useful in identifying host genes that have the strongest influence on limiting the spread of viruses between species; such studies should include efforts to identify the corresponding viral mechanisms for overcoming genetic barriers to interspecies transmission.

Human agents

Evolution of Chlamydia trachomatis

Ian N. Clarke

inc@soton.ac.uk

We know surprisingly little about the recent evolutionary origins of chlamydia (C. trachomatis) as a sexually transmitted agent of infection. Research has been severely restricted because these bacteria are obligate intracellular pathogens, hence clinical samples taken for isolation of C. trachomatis have to be handled in the same way as swabs taken for virus isolation. Live C. trachomatis was first cultivated in hens’ eggs, but isolation in tissue culture took a long time to perfect. While the isolation of chlamydial strains requires expertise in mammalian cell culture systems, the antibiotics used to suppress the contaminating bacteria for virus isolation, such as streptomycin and penicillin, also inhibit C. trachomatis, and this confounded early attempts to develop cell culture systems that supported C. trachomatis. Furthermore, genital tract strains of C. trachomatis have low infectivity, and thus centrifugation is required to ensure these bacteria can infect susceptible, cultured mammalian host cells. C. trachomatis retains viability in long-term storage only if kept at ultra low temperatures and with stabilizing cryopreservatives; consequently, there is a paucity of historical isolates.

Since the advent of rapid and sensitive nucleic acid amplification tests over the past 15 years, most diagnostic laboratories have stopped attempting to diagnose C. trachomatis infections by isolation and these skills are rapidly becoming a “lost art.” The American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) holds a small collection of isolates that cover all of the genital tract serotypes, and it is mainly these strains, chosen for their ability to grow well in the laboratory, that have been the focus of laboratory-based studies. From limited phylogenetic studies, using either fragments of the chromosome or using whole genomes, it is clear that C. trachomatis can be divided into two distinctive groupings. These also reflect the groupings of isolates on the basis of their biological properties. Thus there are the highly invasive and rapidly growing strains that make up the “lymphogranuloma venereum” biovar that appear to be the more ancient lineage. Branching from this comes the trachoma biovar, which comprises two different sets of strains: those from the eye and those from the genital tract.

From the first few genomes analyzed, it appeared that the C. trachomatis genome was monomorphic. These first genomes possessed high synteny and extremely high sequence conservation with as little as 20 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) accounting for differences between some strains.65 A comprehensive analysis of the nature and extent of genome diversity is now required by collecting as many different isolates/genomes from around the world as possible. This will define the chlamydial pan-genome. Recent indications from partial genome analyses suggest that recombination is a mechanism for generating diversity,66 and a comprehensive genome-sequencing program will allow evaluation of this process and elucidate possible mechanisms and the forces that drive the generation of diversity. While sexually transmitted C. trachomatis appears to be an exclusively human disease, the evolutionary origins of the infection are unclear.67 There is no accurate molecular clock by which to measure the evolution of C. trachomatis. It has been speculated that chlamydial infections are an ancient disease and their evolution has been closely linked to that of their human host. However, quite closely related chlamydia have been isolated from other species (e.g., pigs and mice) but there is only very little knowledge of the presence of chlamydia in higher primates.68 A detailed investigation screening wild primates for chlamydia might be profitable in illuminating the evolutionary origins of this bacterial species.

The recent emergence of the Swedish new variant illuminates the importance of understanding how strain diversity is generated and focusing attention on the plasmid as well as the genome. In the case of the Swedish new variant “selection” was by failure to detect the strain because of mutations within the plasmid and the subsequent absence of treatment and contact tracing follow-up.69 Attempts to identify precisely when the strain appeared in the Swedish population suggest that the primary event (emergence or introduction) occurred very recently. The way the Swedish new variant was able to spread rapidly in the population is a cause for alarm. Certainly some significant lessons have been learned, the most important that the chlamydial population is not merely a static isolated backwater with limited potential for adapting rapidly to a changing world. The second is that at least two targets should be used for detection, thereby insuring that the new generation of nucleic acid amplifications tests should all conform to this criterion. Recent studies suggest that the plasmid is a virulence factor and critical for the spread of C. trachomatis in the population.

The widespread use of antibiotics has created additional concerns that antibiotic-resistant strains of C. trachomatis might be created in the future, and these could be disseminated as apidly as the Swedish new variant.

Haemophilus ducreyi and Klebsiella granulomatis

Teresa Lagerård

teresa.lagergard@microbio.gu.se

Haemophilus ducreyi is a sexually transmitted, obligate human pathogen that primarily infects skin as well as epithelial surfaces in the genital tract and causes local, persistent ulcers (chancroid). This disease is most commonly seen in developing countries and is recognized as a cofactor in the transmission of HIV-1.70

This Gram-negative bacterium was classified to family Pasteurellaceae, genus Haemophilus based on morphology of cells and nutrition requirements. Later studies based on nucleic acid methodology showed that the phylogenic structure of the family is more complex. Based on sequence studies of 16SrRNA and different housekeeping genes, H. ducreyi was shown to differ from the majority of family members and is less related to the typical Haemophilus cluster. Based on studies of 50 highly conserved housekeeping gene sequences, it was shown that H. ducreyi together with Mannheimia haemolytica and Actinobacillus pleuropenaumoniae forms a group that is divergent from the other Pasteurellaceae.71 Relationship between species in this group are, however, less obvious, because the chancroid bacterium is a human genital pathogen and the two other species are both animal commensals/pathogens in respiratory tract. Taken together, the phylogenic position of H. ducreyi in relation to other Pasteurellaceae is still not clear.

It is known that bacterial genomic fluidity and adaptation to the environment play an important role in diversity and reflects ability in colonization or in development to a successful pathogen. Different species acquired their virulence genes from another species through, for example, horizontal gene transfer, to better adapt to grow and survive. H. ducreyi has a rather small genome (1.8 Mb). The bacterium does not show pronounced genetic variation concerning antigens and virulence factors of different isolates. This may indicate a good adaptation to the genital tract in humans according to the rule that the level of genetic variability that maximizes the fitness of the population varies with the degree of its adaptation to the environment: low when the environment is stable and high when the environment is variable. The genetic bases for adaptation of H. ducreyi to its ecological niche are unknown. The bacterium, however, developed the strategies to adhere to each other and to attach to the epithelial cells, to compete with skin/genital bacteria for nutrition, to produce toxins that destroy host cells, and to survive, despite generating vigorous innate and adaptive immune responses. It can persist in lesions probably by killing cells involved in immune response as well as cells involved in epithelialization.72 Moreover, the bacterium harbored some resistance plasmids from other bacteria, helping it to survive antibiotic treatment. Since H. ducreyi is not known to colonize ecological niches other than the genital tract; sexual contact seems to be the only way to transfer pathogen to other hosts. This successful sexually transmitted infection (STI) pathogen probably evolved the ability to persist in the genital tract lesions, causing a lingering type of disease in order to maximize its transmission fitness as many other STI pathogens do.

Another strictly human pathogen and sexually transmitted Gram-negative bacterium causing genital ulcers is Calymmatobacterium granulomatis— the etiologic agent of donovannosis (granuloma inquinale). This disease is uncommon, with a curious geographical distribution of “hotspots” in Papua New Guinea, South Africa, India, and Australia. The lesions are presented on the genitals/perianal area and start as raised nodules (granulomas), and subsequently erode to form granulomatous, red ulcers that gradually increase in size and can persist for a long time. Two studies contributed to the evaluation of the taxonomic position of C. granulomatis using 16rRNA and phoE gene sequences.73,74 Both studies showed a close relationship with Klebsiella pneumoniae and K. rhinoscleromatis. Carter et al. proposed that C. granuomatis should be reclassified as K. granulomatis comb. nov.73

The high degree of similarity of K. granulomatis to K. pneumoniae on the basis of DNA is interesting because the bacteria differ profoundly in their ecological niches and also probably their pathogenic mechanisms. K. pneumoniae bacteria are found in soil, water, cereal grains, and the intestinal tract of humans and other animals. They are extracellular microorganisms causing pneumonia, wound, soft tissue, and urinary tract infections, and are easy to cultivate on artificial media, while K. granulomatis is known as an intracellular pathogen found in monocytes and is difficult to cultivate.

There are many unsolved questions concerning the evolution of H. ducreyi, such as (i) the origin, development, regulation, and expression of H. ducreyi virulence factors; (ii) what environmental stimuli may influence genome plasticity and what mechanisms do the bacterium use to respond to environmental changes? and (iii) what communication takes place among incoming pathogens, host cells, and resident microflora in genital tract epithelium/skin?

More information is definitely needed to understand the genetic and host factors related to the pathogenesis, immunology, and evolution of K. granulomatis. Such studies could help to ex-plain the possible selective factors responsible for the adaptation to the genital econiche of the Klebsiella gut organisms, and their particular sexual transmissibility in certain geographical “hot spot” populations of the world.

Understanding bacterial genome dynamics, including that of H. ducrey and K. granulomatis, has important consequences for the development of antibiotic resistance and clinical management of the disease, development of diagnostics tools, and new molecular epidemiological methods. Genome instability and variable antigenic repertoire may have a serious impact on the development of therapeutic interventions against infection disease (e.g., vaccines) and the protective efficacy of vaccines and impact in selection of new pathogenic variants.

Genetic diversity of Treponema pallidum

Sheila A. Lukehart

lukehart@u.washington.edu

Four very closely related human pathogenic Treponema species have been identified as Treponemapallidum subspecies pallidum (venereal syphilis), pertenue (yaws), endemicum (bejel) and Treponemacarateum (pinta). Limited isolates of the T. pallidum subspecies are available for study, and no known isolates of T. carateum exist. Pathogenic treponemes, including those causing genital lesions, also exist in nonhuman primates;75,76 only one isolate is known to exist.77 A decades-old “nature” versus “nurture” argument exists about whether the disease manifestations of treponemal infections have a genetic basis or are due to environmental factors (e.g., heat, aridity).78,79 Analysis of existing strains shows that genetic diversity is limited primarily to the tpr paralog family and a few other genes.80–82 Phylogenetic analysis of the tpr gene family in these strains supports division of this species into three human sub-species.81,83 Despite claims to the contrary,84 it is not possible to tell which subspecies is ancestral.83,85

It is doubtful that there is a biological basis for the sexual transmission of T. p . pallidum , compared to the nonvenereal transmission of the pertenue and endemicum subspecies. It is well recognized that T. p. pallidum can cause non-genital and non-mucosal primary infections (e.g., chancres on the shaft of the penis [nonmucosal], digital chancres in dentists prior to universal precautions, and breast ulcers in wet-nurses). Conversely, treponemes associated with severe genital lesions in baboons are more closely related to the pertenue subspecies than to pallidum.76 Careful analysis of the genes comprising the tpr family reveals genetic diversity even within the pallidum subspecies, with five distinct groups identified within the pallidum isolates (unpublished results). There are no data on the respective infectiousness among the species, subspecies, or groups within subspecies.

The two related issues that most impede our knowledge of the evolution of the pathogenic Treponema are the inability to culture this organism in vitro and, consequently, the very limited number of human and animal isolates available for study. It is only recently that investigators have appreciated the genetic diversity represented by these organisms and the wealth of information that can be gained by examining isolates other than the standard Nichols type strain.

A new enhanced molecular typing method,86 based upon genetic diversity among strains, can divide T. p .pallidum isolates into molecular strain types, with discriminatory capability far surpassing that of previous typing schemas.87 This will permit public health officials and epidemiologists to map sexual networks and to identify specific population groups for more effective syphilis control interventions. Studies of genetic diversity may also lead to the ability to predict which patients are infected with strains that are more likely to cause serious disease. The first association of genotype to clinical outcome in syphilis has been reported, in which molecular strain type 14d/f was significantly associated with neurosyphilis than were seven other strain types circulating in Seattle, Washington between 1999 and 2008.86 If future studies confirm associations between type and outcome, clinicians maybe better able to determine which patients could benefit from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination for neurosyphilis or from more intensive treatment.

Evolution and diversity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Magnus Unemo and William M. Shafer

magnus.unemo@orebroll.se

In this paper, current knowledge of the evolution and diversity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and remaining research questions in the field as well as public health importance of solving these questions are discussed.

Gonorrhea is the second most prevalent bacterial STI globally and a major public health concern that, in the near future, may become untreatable in certain circumstances, that is, due to the absence of a vaccine and the rapid development and spread of resistance to all antimicrobials introduced for treatment.88 Gonorrhea has been recognized for thousands of years, for example, it is referred to in the Bible (Leviticus). However, the phylogenetic origin of the etiological agent, N. gonorrhoeae, is not completely elucidated, but taxonomically it belongs to the Phylum Protobacteria, Taxa (3-proteobacteria, Order Neisseriales, Family Neisseriaceae, and Genus Neisseria. The Neisseria genus contains many human commensal species but only two human pathogenic species—N. gonorrhoeae (obligate pathogen) and N. meningitidis. N. meningitidis causes meningitis and/or septicemia, however, the bacterium is also frequently found in the (naso)pharynx of healthy carriers. N. gonorrhoeae has instead been adapted to effectively adhere to and invade urogenital nonciliated columnar epithelial cells, but also conjunctival, anorectal, and pharyngeal epithelium. By using mechanisms such as antigenic and phase variation of outer membrane structures, blocking antibodies, molecular mimicry (e.g., lipooligosaccharides [LOS]), sialylation of LOS, inhibition and/or induction of apoptosis, and rapid development of resistance to all antimicrobials introduced for gonorrhea treatment, this “master of survival” has effectively adapted to new ecological niches and evaded host immune systems, new antimicrobial treatments, and other interventions.89 N. gonorrhoeae displays an extensive and frequent horizontal gene transfer (partial or whole genes) within the species and with closely related species, using transformation (natural competence during its entire life cycle) including usage of a specific DNA uptake sequence (DUS)90 and conjugation (plasmid DNA). This, combined with a high mutational frequency in many genes and a substantial number of phase-variable genes, causes an exceedingly high heterogeneity in the N. gonorrhoeae population. In fact, N. gonorrhoeae has a nonclonal, sexual, and panmictic population structure, which is rare for bacterial species. Relatively few N. gonorrhoeae genomes have been published, and genome studies to elucidate the origin and phylogeny of all human Neisseria species have been rare. The size of the N. gonorrhoeae genome is ∼2.1–2.2 Mbp (∼2,000 predicted genes), and it shares nearly 900 core genes, mostly with housekeeping functions but also many virulence genes, with all other humanNeisseria species.4 The apparent widespread exchange of virulence, metabolic, adaptation, and antimicrobial resistance genes (whole or partial genes) among human Neisseria species and the commensal Neisseria species seem to represent an extensive reservoir for these genes (“shareable gene pool”). The prevalence of several Neisseria species in the same ecological niches in the human body provides an excellent opportunity for a high frequency horizontal gene transfer, which can increase biological fitness, enhance host adaptation, and affect bacterial pathogenicity/virulence.91 Most human Neisseria species share the majority of the core genome as well as the “pathogenome,”91,92 and the Neisseria genus seems to comprise an open pan-genome. Accordingly, relatively few gene complements (and gene combinations) combined with smaller genetic differences (single nucleotide polymorphisms [SNPs] and insertions/deletions [indels]), gene expression, and regulation (e.g., ON/OFF phase switching of genes under certain circumstances) seem to differentiate the divergent Neisseria species. The genomes of the two pathogenic Neisseria species, N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae, form a distinct monophyletic clade that is derived from the commensal Neisseria genomes. Compared to all Neisseria commensal species, the two pathogenic Neisseria species have some gene differences, such as additional silent pilS loci (increased antigenic variation of Type IV Pilus) and opa genes (enhanced antigenic variation of the outer membrane Opa proteins), which can be important for enhanced adaptation, antigenic diversity, and attachment to and invasion of host cells. Genomic (as well as biochemical, morphological, and antigenic) differences between the two pathogenic Neisseria species, which result in the widely different preferred ecological niche, infection spectrum, and epidemiology, are relatively few.91 One plausible theory regarding the origin and evolution of pathogenic Neisseria species may be that the pathogenic Neisseria species, when evolving from the human commensal Neisseria species, obtained additional genes such as porA (encoding a second porin [PorA]), iga (IgA proteases cleaving human IgA), lamp1 (lysosome-associated membrane protein 1), and additional opa and pilS loci. For the speciation of N. gonorrhoeae, the porA evolved into a pseudogene (possibly for enhanced preference for urogenital and a wider ecological niche), and outer membrane protein A (OmpA), additional opa, and pilS loci (possibly for enhanced adaptation, antigenic diversity, evasion of host immune response, and adherence to and invasion of epithelial cells in different ecological niches) were acquired.

Many questions regarding the origin, evolution, and entire population structure of N. gonorrhoeae remain. It would be valuable to have a substantially higher number of finished and closed (with high confidence) N. gonorrhoeae genomes, and appropriate comparisons of these genomes in many different aspects involving population structure, genome (pan, core, dispensable genome, and possible pathogenome), evolution (in vitro and in vivo, i.e., in different hosts, anatomical sites, and sexual networks), and also preference of ecological niche, pathogenesis, virulence, and biological fitness. Furthermore, adequate and well-designed studies combining genomics (including investigations of small gene variations such as SNPs and indels, and highlighting the importance of retained pseudogenes); transcriptomics (gene expression and regulation); proteomics; immunobiological–physiological experiments; and, ideally, also involving host factors would be exceedingly valuable. Finally, new models using modern methodologies for more precise studies, for example, regarding single cell genomics and expression, interplay between different cells and mechanisms, and genomics on non-cultured, primary samples (reflecting the entire population and possible mixed infection) would be the way forward.

The importance and future benefits for management of bacterial STIs (both case and population level) and the public health purposes of using new technologies, epi- and/or metagenomics, expression analysis, and evolution are large and numerous. For instance, the complete phyologenetic origin, evolution, and even predictions of future evolution of N. gonorrhoeae might be possible to elucidate. This would result in enhanced knowledge regarding mechanisms for emergence, evolution, and transmission of single bacterial strains in human and bacterial population (locally and globally), greater understanding of altered biological fitness, and the basis for more successful N. gonorrhoeae clones. We would also obtain an enhanced understanding regarding pathogenesis, virulence, and immunobiology (natural course of infection, asymptomatic infection, and complications). Furthermore, the data provided would improve diagnostics (new technologies, new targets [essential and multicopy], understanding of evolution of targets [inter- and intrapatient in different sexual networks], and appropriate point-of-care (POC) tests) as well as enhance the molecular epidemiological typing used to describe the N. gonorrhoeae population that circulates globally, including its dynamics (new technologies and thinking [possibly using genomic SNP-based typing], new targets, and evolution of targets [inter-and intrapatient]. Finally, we would be able to develop more effective treatment regimens (new drugs and drug targets including evolutionary stability of and selective pressure on these, tailor-made antimicrobials [+/– adjuvants/immunomodulators], antibacterial peptides, microbiocides, prediction of antimicrobial resistance emergence, effects on biological fitness, and mechanisms for spread of more successful resistant strains worldwide) and enhanced prevention of gonorrhea (contact tracing, treatment failures, sexual networks, new vaccine candidates [possibly using reverse vaccinology to identify genome-derived immunogens], and new ways to administer vaccines.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae and drug resistance

William M. Shafer and Magnus Unemo

wshafer@emory.edu

In the absence of vaccines, we rely on the efficacy of diagnostics and subsequent antibiotic treatment to stop the spread of bacterial agents that cause sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Clinically, of the main bacterial agents of STIs, only Neisseria gonorrhoeae (the gonococcus) has developed resistance to multiple antibiotics, which has necessitated major changes in drug treatment regimens over the past decades.93,94 Hence, gonococci serve as a good model system for studies on the evolution of STI bacteria and development of antibiotic resistance.

It is important to remember that gonococci have spent thousands of years infecting humans, and over the millennia the bacterium has adapted itself for survival; hence, its capacity to develop resistance to antimicrobials used clinically to treat infections should not be surprising. In relationship to the evolution of antibiotic resistance in N. gonorrhoeae, several important issues need to be considered. First, both gene (whole or parts of a gene) acquisition and spontaneous mutation events (high mutational rate in some resistance genes), which are effectively selected due to antibiotic pressure in the society, are responsible for the development and spread of antibiotic resistance in gonococci. Gonococci have a very efficient transformation system (natural competence for transformation during the entire life cycle) that employs the ubiquitous Type IV pili and a sequence-specific uptake system. The bacteria also have a conjugation system, but this is less efficient and the conjugal plasmid, which can carry the tetM determinant (causing tetracycline resistance), fails to mobilize chromosomal genes. Often, gonococci initially acquire DNA sequences involved in antibiotic resistance by transformation from commensal neisserial species, and these resistance determinants can then spread among gonococcal strains. Pharyngeal gonorrhea, where gonococci frequently coincide with commensal neisserial species, may be an effective, asymptomatic reservoir both for infection and initial emergence of antibiotic resistance, by transformation, in gonococci. For instance, commensal neisserial species can harbor a penA allele that encodes a penicillin binding protein (PBP) termed PBP2, which has reduced affinity for beta-lactam antibiotics compared to the wild-type PBP2 produced by gonococci sensitive to beta-lactams. Since PBP2 is the lethal target for beta-lactam antibiotics, remodeling of PBP2 decreases gonococcal susceptibility to beta-lactams and further genomic changes due to spontaneous mutation or acquisition of alleles of other genes (e.g., those encoding the MtrC–MtrD–MtrE efflux pump, porin, secretin, or PBP1), can further reduce beta-lactam susceptibility.93,94 The demise of penicillin as a first-line antibiotic was the result of at least five such events in a 1983 clinical isolate from Durham, NC.95 The importance of spontaneous mutations in the evolution of antibiotic resistance can be learned from how gonococci developed resistance to quinolones as this involved spontaneous mutations in gyrA and parC.93,94 Once these mutations developed, they were rapidly transferred to sensitive gonococci by the highly efficient transformation system.

A second important issue to consider is why resistant strains persist in the community despite removal of the antibiotic from therapy, that is, causing a loss of selective pressure. Do these strains have a fitness advantage (or at least lack a fitness disadvantage) over wild-type strains in the community? Results from experimental murine vaginal infection studies showed96 that strains possessing an mtrR mutation (causing enhanced production of the MtrCDE efflux pump and most probably altered regulation of other chromosomal genes94), which is needed for high level penicillin resistance, are more fit in vivo than strains with the wild type allele. Certainly, however, antibiotics used to treat other bacterial infections, inappropriate use of the antibiotic, or antigonococcal agents used topically to prevent STIs and HIV transmission or pregnancy (e.g., the spermicide nonoxynol-9) could inadvertently maintain selective pressure in the community for resistant strains.

The recent emergence of strains in the Far East, especially in Japan, with decreased susceptibility and resistance (one strain reported97) to third generation cephalosporins including ceftriaxone, the internationally recommended and main class of antibiotic used today, and the global spread over the past 25 years of strains resistant to relatively cheap antibiotics (e.g., penicillin, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline) highlight the critical and immediate need for new antibiotics to treat gonorrhea. In fact, gonorrhea may become untreatable in certain circumstances and settings.93 Strains expressing decreased susceptibility (and now one single strain displaying high-level resistance97) to ceftriaxone should remind us of those gonococci in late 1950s and 1960s94 that expressed decreased susceptibility to penicillin and the subsequent emergence of strains expressing higher levels (i.e., chromosomal and not caused by beta-lactamase production) of resistance. Clearly, history is repeating itself and lessons learned from how gonococci developed resistance to penicillin are applicable to how they will most likely develop clinical resistance to ceftriaxone that rapidly spread globally.

For bacteria in general, and for gonococci in particular, unfortunately, no “rediscovery” of effective older antibiotics or new antibiotics with unique targets are in the immediate future. However, recent advances in research laboratories give some hope and may have applications for treating gonorrhea when ceftriaxone-resistant strains spread globally. Of these new antimicrobials, which specifically targets multidrug resistant bacteria, are efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs). These EPIs block the energy-dependent export action of efflux pumps rendering the target bacteria susceptible to antibiotics that are pump substrates. These EPIs could poison the gonococcal MtrCDE efflux pump, which based on earlier studies (reviewed in Ref. 94) would make the target gonococcus susceptible to penicillin. Moreover, extrapolation of the results from the murine vaginal infection model in which MtrCDE pump deficient mutants were unable to cause a sustained vaginal infection and were more rapidly cleared than the wild type strain (also reviewed in Ref. 94), predicts that poisoning the pump would diminish bacterial fitness in vivo. Additional antimicrobials currently in the developmental phase deserve mention. One class of antimicrobials is the host defense, cationic pep-tides, such as the human cathelicidin LL-37 that can have both direct and indirect antibacterial action. LL-37, for instance, is antigonococcal directly, but is also a substrate for the MtrCDE pump (reviewed in Ref. 94); again, poisoning the pump with EPIs could render gonococci more susceptible to the antibiotic-like action of LL-37. Finally, novel inhibitors of enzymes involved in lipid A biosynthesis, for example, LpcC inhibitors, are being studied by R. Nicholas and coworkers (personal communication, 2011).

In the absence of new antimicrobials on the immediate horizon, we need to consider use of increased doses or multiple doses of third generation cephalosporins or possibly other antibiotics, which, however, only offer limited hope for long-term effective treatment. Furthermore, combination therapy (several antibiotics administered at the same time point) needs to be strongly considered for use and further evaluated in appropriate studies. In this respect, a combination of gentamicin and the new formula of azithromycin (with enhanced gastrointestinal tolerability) have been suggested as an alternative therapy; however, possible undesirable side effects will need to be considered and monitored. Finally, it may be crucial to maximize local surveillance efforts to identify those strains that have remained susceptible to antibiotics, including those used previously, but removed from treatment regimens due to high prevalence of resistance. Thus, if in a community there are strains that remain susceptible to such antibiotics, which are no longer recommended by national healthcare agencies, then such antibiotics should be used anyway if warranted (microbiologically directed treatment). Certainly, this will be a point of contention, but curing the patient and stopping local spread of gonorrhea are the objectives, and if this means culturing and doing antimicrobial susceptibility testing, which will be expensive, to accomplish this, then this option must be seriously considered and used by local health care providers. Rapid sequencing technologies can help in identifying resistant and sensitive strains since mutations needed for resistance can be detected. Nevertheless, in regards to the last remaining options for treatment, that is, the third generation cephalosporins, knowledge remains lacking and better correlates between different genetic polymorphisms, in vitro determined antimicrobial susceptibility, and outcome of clinical therapy are essential. For enhanced knowledge regarding these issues, genome sequencing of additional isolates displaying decreased susceptibility and resistance to third generation cephalosporins combined with biological studies would be exceedingly valuable. A concerted effort to develop appropriate point-of-care sequencing technologies for this purpose is required to bring such technology to the clinic.

We need to ask: how (and when) will clinically significant levels of gonococcal resistance to third generation cephalosporins develop, will such resistance provide a fitness advantage or disadvantage to these strains, and how quickly will the resistant strains spread globally? These issues can be addressed by more detailed studies on the genetics and molecular biology of resistance, fitness studies, and studies regarding mechanisms of national and international spread (including modeling in different populations) of ceftriaxone-resistance as resistant strains emerge and spread. We can then use this information with DNA sequencing studies to rapidly identify such strains and catalog mutations in different genes or new genes that contribute to such resistance. In relationship to new antimicrobials that come into clinical practice, investments into antibiotic development and basic studies on resistance, including in vitro development and selection of resistance, must continue and be enhanced. How will resistance to current and future antibiotics impact fitness in the community? To address this issue, we must maximize our surveillance efforts to learn if resistant strains, based on different antimicrobial resistance mechanisms, have a fitness advantage (or disadvantage) in the community.

Epidemiology and evolution of hepatitis viruses

R. Palmer Beasley

r.p.beasley@uth.tmc.edu

Introduction and characteristics of the five hepatitis viruses

Substantial research has resulted in a rapidly expanding body of knowledge about the hepatitis viruses, their epidemiology, transmission modes and, more recently, their possible origins and evolutionary progression. The five hepatitis viruses, grouped because of their hepatotropism and inflammation of the hepatic parenchyma, have little else in common and almost certainly have no common evolutionary pathway. This paper summarizes current knowledge on classification, transmission, origin and evolution of the hepatitis viruses. Several schemata are used to classify viruses including clinical, epidemiological (transmission), nucleic acid type, and replication cycle. The classification, developed by David Baltimore, uses genome composition and structure, and method of replication all possibly helpful for understanding evolution. The morphology and classification of hepatitis viruses A through E are summarized in Table A1. Hepatitis A and C (and GVB) are Class IV RNA viruses, HBV is a Class VII DNA virus, HDV and HEV are as yet unclassified RNA viruses. The lettered names now used for the hepatitis viruses was adopted following the recommendation of Robert MacCallum in the 1970s as it was becoming apparent that the descriptive names then in use were inaccurate and misleading. Thus, infectious hepatitis became hepatitis A and serum hepatitis became hepatitis B. The next agent was called non-A non-B for several years before the agent was identified and named hepatitis C. The next agent, initially called the delta agent, fit well into the alphabetic sequence when its viral nature was established and was renamed HDV. Hepatitis E was initially called the New Delhi hepatitis agent, then non-A, non-B, non-C before becoming HEV. There was a brief claim to HFV, which was not substantiated, and then HGV, which exits but doesn’t seem to cause hepatitis and is now called GVB. Irrespective of its classification, the GVB virus remains of evolutionary interest because it is most closely related to HCV.

Table A1.

Hepatitis virus classification and characteristics

| Morphology |

Classification |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Nucleic Acid |

Structure | Baltimore class |

Diameter (nm) |

Nucleotides Base pairs |

Family | Genus | Genotypes |

| A HAV | RNA | ss+ strand | IV | 25 | 7,500 | Picorna | Hepato | 3 |

| B HBV | DNA | ds circle (RT) | VII | 42 | 3,200 | Hepadna | Orthohepadna | 8 |

| C HCV Delta | RNA | ss+ strand | IV | 55–65 | 9,500 | Flavi | Hepaci | 6 |

| D HDV | RNA | ss circular | ? | 36 | 1,700 | Not assign | Delta | 3 |

| E HEV | RNA | ss+ strand | ? | 32–34 | 7,200 | Not assign | Hepe | 4 |

Incubation period and clinical spectrum

Long-incubation periods are generally characteristic of the hepatitis viruses. While the incubation periods for HBV and HCV are generally longer than for HAV or HEV, high variability of the incubation periods is characteristic of all of the hepatitis viruses, probably relating to dose, route of infection, a variety of poorly characterized host factors, and possibly viral strain differences (Table A2).

Table A2.

Clinical characteristics of hepatitis virus infection

| Clinical characteristics |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | Incubation period (weeks) |

Acute hepatitis |

Chronic hep |

Chronic outcomes |

|||||

| Asymp | Moderate | Fulminant | Viral persistence |

Cirrhosis | HCC | ||||

| HAV | 2–6 | Common | Usual | Rare | No | No | No | No | |

| HBV | 4–20 | Common | Common | Occasional | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| HCV | 2–26 | Common | Common | Rare | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| HDV | 3–7 | Common | Common | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yesa | |

| HEV | 2–10 | Common | Common | Rare | No | No | No | No | |

HDV increases the risk associated with HBV.

The clinical spectrum and natural history of infection is also highly variable.98–100 The acute response to all five viruses ranges in severity from asymptomatic to severe acute illnesses with hepatic failure with occasional deaths. Persistent infections may occur with HBV, HCV, and HDV with infections of any severity, but more commonly when the initial infection is mild or asymptomatic, and are probably determined by immunological factors. Hepatitis infections are usually asymptomatic in infants and children. HEV in pregnancy is well known for its severity and high mortality.101 Infection with more than one hepatitis virus may result in more severe illness and higher mortality rates. HDV infection markedly aggravates the course of HBV.

Chronicity and carriers

Chronic carrier states, often lifelong, sometimes follow infections with HBV and HCV. HDV may persist with chronic HBV infections. The probability of chronicity for HBV is inversely related to age of the person when infected. There is no evidence for this age effect with HCV.

Immunology

Resolved hepatitis infections result in long-lasting protection from reinfection, so that recurrent episodes of acute hepatitis are due either to infections with different virus types or acute/subacute relapses of chronic infections (HBV and HCV). First infection immunity appears to preclude recurrent new infections with the same virus. Periodic clinical relapses in carriers can appear as recurrent new infections with HBV and HCV, or even HDV can resemble reinfections.

Highly immunogenic commercial vaccines, which induce long-term protection exist for HAV and HBV. Experimental vaccines for HDV and HEV have also shown protection, while a satisfactory vaccine against HCV is still to be developed.

Human hepatitis viruses in animals

HAV, HCV, and HDV appear to be confined to humans in nature (Table A3). A number of wild mammals and birds are infected with hepadna viruses, similar to HBV, which provides interesting clues regarding the origins and evolution of this group, as discussed below.102,103 Pigs and chickens are frequently infected with HEV- or HEV-like agents. Strains from pigs, but not chickens, appear to be infectious to man, and there is increasing data suggesting that swine are the origin, if not the current reservoir, for human infections.7

Table A3.

Occurrence of human hepatitis viruses in animals

| Human virus infections in animals |

Similar animal viruses in nature |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Lab | Nature | Primates | Other mammals |

Birds | Transmission to humans |

Viral persistence |

| A | Yes | No | No | No | No | N/A | No |

| B | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| C | Chimps | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| D | Yes | No | No | No | No | N/A | Yes |

| E | Yes | No | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unknown |

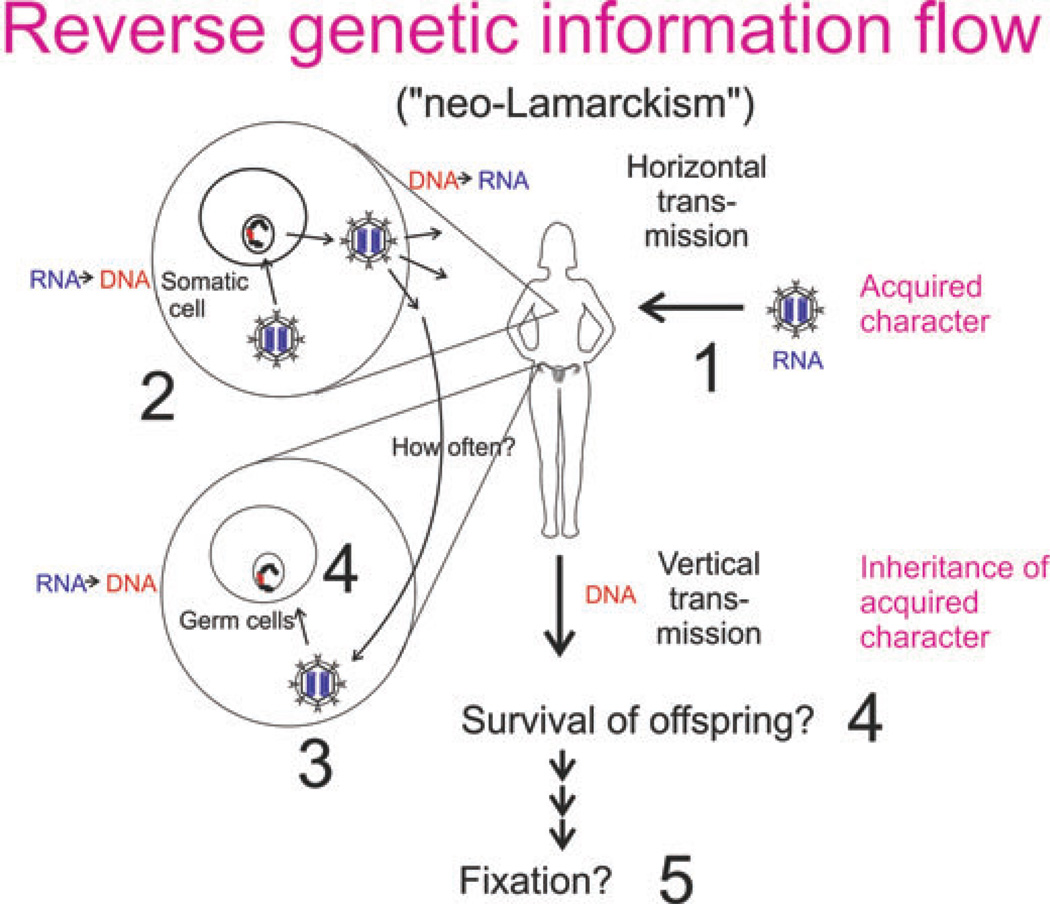

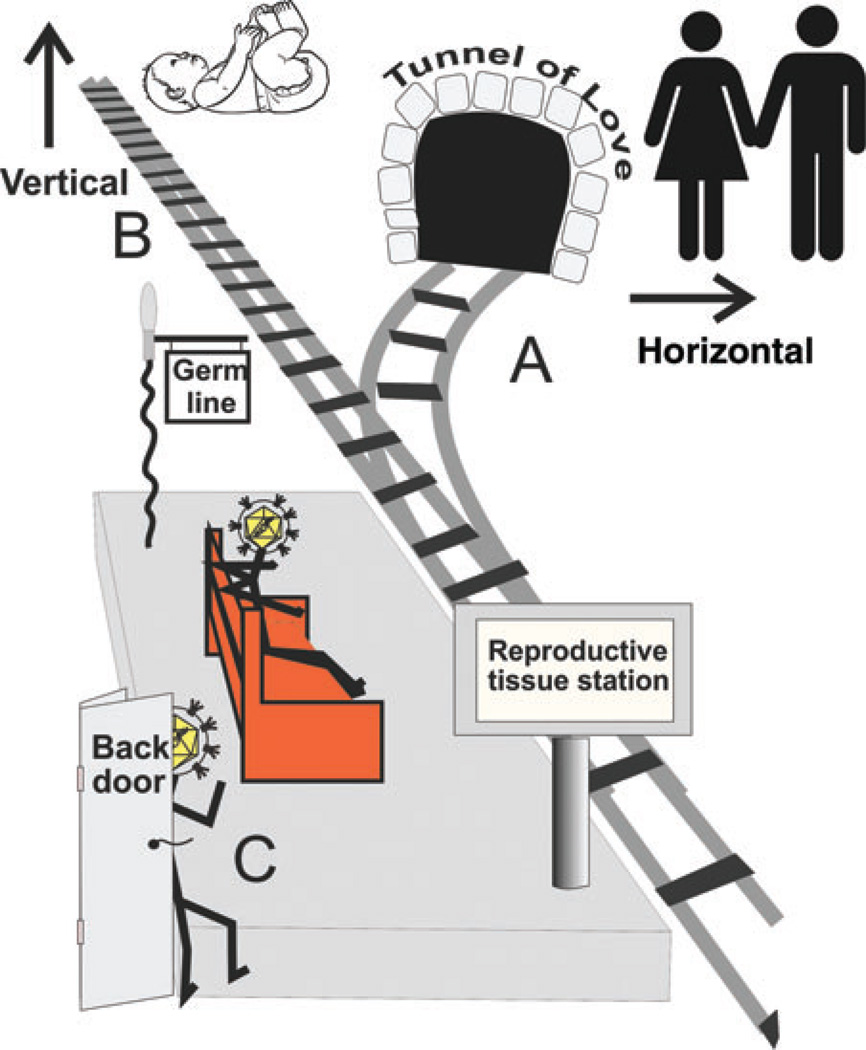

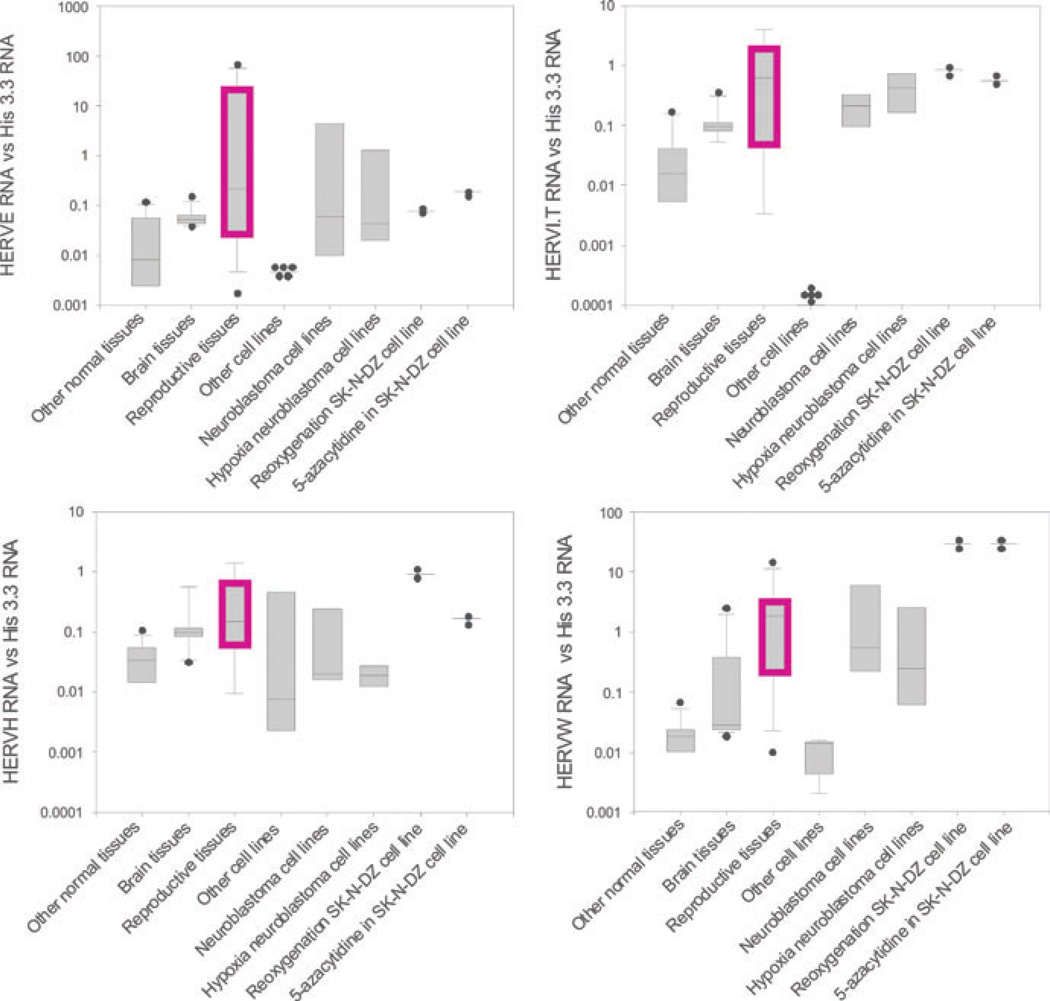

Geographic distribution and transmission