Abstract

BACKGROUND

The use of serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and progesterone to identify patients with ectopic pregnancy (EP) has been shown to have poor clinical utility. Pregnancy-associated circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) have been proposed as potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of pregnancy-associated complications. This proof-of concept study examined the diagnostic accuracy of various miRNAs to detect EP in an emergency department (ED) setting.

METHODS

This was a retrospective case-control analysis of 89 women who presented to the ED with vaginal bleeding and/or abdominal pain/cramping, and were diagnosed with viable intrauterine pregnancy (VIP), spontaneous abortion (SA), or EP. Serum hCG and progesterone concentrations were determined by immunoassays. Serum miR-323-3p, miR-517a, miR-519d, and miR-525-3p concentrations were measured using TaqMan real-time PCR. Statistical analysis was performed to determine the clinical utility of these biomarkers as single markers and as multimarker panels for EP.

RESULTS

Concentrations of serum hCG, progesterone, miR-517a, miR-519d, and miR-525-3p were significantly lower in EP and SA than in VIP. In contrast, the concentration of miR-323-3p was significantly elevated in EP as compared to SA and VIP. As a single marker, miR-323-3p had the highest sensitivity of 37.0% (at a fixed-specificity of 90%). Comparatively, combined hCG, progesterone, and miR-323-3p panel yielded the highest sensitivity of 77.8% (at a fixed-specificity of 90%). A stepwise analysis using hCG, then progesterone, and then miR-323-3p resulted in 96.3% sensitivity and 72.6% specificity.

CONCLUSIONS

Pregnancy-associated miRNAs, especially miR-323-3p, added significant diagnostic accuracy to a panel including hCG and progesterone for the diagnosis of EP.

Keywords: Ectopic pregnancy, MicroRNAs, Biomarkers, Diagnostic accuracy

Introduction

Ectopic pregnancy (EP) occurs when a conceptus implants outside the endometrial cavity. Although only 1.3-2% of all pregnancies are ectopic, the prevalence of EP is 6-16% among pregnant patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) with vaginal bleeding and/or abdominal pain (1). Patients are at risk of tubal rupture and death. This condition contributes to 9-13% of pregnancy deaths in developed countries and 10-30% in African developing countries (2). The diagnosis of EP is made by transvaginal ultrasonographic identification of an extrauterine gestational sac containing a yolk sac. However, surgical or biochemical assessment is necessary when ultrasound is not definitive, as occurs in approximately 8-31% of patients seen in specialty centers (3).

Serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and progesterone have been the most intensively investigated biochemical markers for the diagnosis of EP. However, a single measurement of hCG or progesterone is primarily an indication of pregnancy viability rather than location, and is thus insufficient to diagnose EP. Alternatively, the approach of serial hCG monitoring is often used for patients with bleeding and/or pain in early pregnancy (4). American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) suggests that viable intrauterine pregnancy (VIP) is associated with an increase in hCG concentration of > 53% in 48 hours (5). However, as with a single measurement, serial serum hCG measurements cannot identify the location of the gestational sac and are only useful to prove fetal viability rather than to identify EP. Using the approach of serial serum hCG measurements, patients are at risk of tubal rupture while waiting for the next hCG measurement. Taken together, use of serum hCG and/or progesterone to identify EP is limited by high-false positive and high false-negative rates and difficulties in the distinction between EP and spontaneous abortion (SA). Therefore, there is a compelling demand for the development of new, noninvasive serum tests to diagnose EP with high sensitivity and high specificity to prevent sudden, life-threatening complications and unnecessary surgical or medical management that may result in interruption of a potentially viable pregnancy.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) may serve as improved biomarkers for numerous pathological conditions, including cancer, autoimmune diseases, sepsis, acute myocardial infarction, and others (6). In contrast to many biomarkers, miRNAs appear to be highly stable. They are robust enough to tolerate enzymatic degradation, freeze-thaw cycles, and extreme pH conditions (7, 8). Most recently, identification of pregnancy-associated circulating miRNAs has generated much interest in investigating their potential roles as biomarkers for the diagnosis of pregnancy-associated complications (9-12). The altered expression pattern of pregnancy-associated miRNAs may reflect tissue-specific physiologic or pathologic states during pregnancy, such as preeclampsia (13-16), preterm labor (17), exposure to toxins (18, 19), and fetal growth restriction (20, 21).

The objectives of this proof-of-concept study were to: 1) identify pregnancy-associated miRNAs with altered serum concentrations in EP; and 2) to investigate their diagnostic accuracy for the detection of EP in patients exhibiting symptoms of vaginal bleeding and/or abdominal pain/cramping in an ED setting.

Materials and Methods

PARTICIPANT RECRUITMENT AND SAMPLE COLLETION

This was a multi-center, retrospective, cohort study between Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN and Washington University in St. Louis, MO. Remnant serum specimens sent to the laboratory from the ED for physician-ordered hCG testing between November 14, 2007 and Novermber 12, 2009 were utilized. Specimens were included if they met the following criteria: serum hCG >5 IU/L, women exhibited symptoms of vaginal bleeding, abdominal pain, and/or abdominal cramping, sufficient serum volume was available to perform progesterone and miRNA testing, patient age ≥18 years, singleton gestation and gestational age (GA) ≤10 weeks. All serum specimens sent to the laboratory for quantitative hCG testing by the ED were retained and frozen at −70°C for less that 42 months before progesterone and miRNA testing was performed. Chart review was performed to determine patient symptoms, ultrasound findings, and pregnancy outcome. All diagnoses had been confirmed by ultrasound, histopathology, serial hCG measurements, and/or clinical follow up. Specimens from Vanderbilt University were shipped frozen to Washington University for hCG, progesterone, and miRNA testing. Human studies committee approval from both institutions was obtained for this study. 34 patients with VIP, 28 patients with SA, and 27 patients with EP were included if they met all of the above inclusion criteria. At the time of serum collection, location of pregnancy was unknown in 7 of the VIPs, 17 of the SAs, and 11 of the EPs. In this study, 13 specimens were from Vanderbilt University and 76 specimens were from Washington University. This was a sub-study of a study examining Activin A as a marker of EP (22). 49 patients from the previous study were included in this study. The rest of the specimens included in the previous study were not included in the present study due to insufficient serum volume. An additional 40 specimens were randomly selected from the cohort of consecutively collected hCG specimens from the ED between December 27, 2007 and November 12, 2009.

RNA EXTRACTION

Total RNA containing miRNAs was extracted from 250 μL serum with Trizol LS following the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen), modified in that samples were extracted twice with chloroform. Total RNA was dissolved in 10 μL of RNAse free water (Mediatech).

QUANTIFICATION OF miRNAs BY REAL-TIME QUANTITATIVE REVERSE TRANSCRIPTION-PCR ANALYSIS

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed following previously described protocol with modifications (23, 24). The sequences for the primers and probes were obtained from previously validated assays and can be found in Supplementary Data Table 1 available with the full text of this article at www.clinchem.org (23, 25). Primers and probes were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. In brief, for each sample, 4 μL of total RNA, 5 nM of each miRNA-specific reverse stem-loop primer and the 18s rRNA reverse primer were added in 10 μL multiplex reverse transcription reaction using High capacity cDNA archive kit (Applied Biosystems). 5 μL RT product was used as template for 25 μL multiplex pre-PCR reaction (18 cycles) containing 5 μmol/L of the universal reverse primer and 50 nmol/L of each forward primer for miRNAs and 50 nmol/L of forward and reversed primers for 18s rRNA. Pre-PCR product was diluted 1:500 and used as template in a singleplex TaqMan real-time PCR reaction containing 0.5 μmol/L of forward primer, 0.5 μmol/L of universal reverse primer, and 0.1 μmol/L of TaqMan-probe. All real-time PCR reactions were analyzed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR. Reaction conditions were 55 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15s and 55 °C for 1 min. The threshold cycle (Ct) values from real-time PCR assays were set within the exponential phase of the PCR. The inter-assay CV of Ct values was <2%. The Ct values greater than 40 were treated as 40. The data were analyzed by comparative method with Ct values converted into fold-change relative to 18S rRNA based on a doubling of PCR product in each PCR cycle (26). 18s RNA has been identified as an endogenous control showing minimal variability according to the manufacturer’s recommendation (Applied Biosystems).

hCG AND PROGESTERONE TESTING

hCG and progesterone concentrations were measured at Barnes-Jewish Hospital/Washington University using commercially available assays by licensed medical technologists who were blinded to outcomes and miRNA results. Serum hCG was assayed by use of the Centaur Total hCG assay (Siemens) and serum progesterone by the Centaur Progesterone assay (Siemens). Both assays were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. The hCG assay had a dynamic range of 5-1000 IU/L and an inter-assay CV of 16%, 8%, and 5% for quality control samples with means of 6, 24, and 360 IU/L, respectively. The progesterone assay has a dynamic range of 1-60 ng/mL and an inter-assay CV of 12%, 7%, and 7% for quality control samples with means of 1.4, 8.5, and 20 ng/mL, respectively.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Patient age, GA, and concentrations of serum hCG, progesterone, and miRNAs were compared among EP, SA and VIP patients. The distribution of these variables is not Gaussian; therefore, the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn’s post hoc test to test for statistical significance. Correlation analysis between concentrations of serum markers and GA was performed in EP, SA, and VIP groups. Multimarker analysis was conducted using multivariate logistic regression to evaluate the predictability of EP versus non-EP based on different combinations of the biomarkers (27). Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed and areas under the curves were calculated. Sensitivity and specificity values were compared via Pearson χ2 analysis or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate. A stepwise analysis using hCG, then progesterone, and then miR-323-3p was performed to optimize sensitivity. The cutoff point of each step was chosen by fixing the sensitivity at the highest level. All statistics were performed with use of either STATA 11.0 (StataCorp) or Prism GraphPad 5.0 (GraphPad Software). Statistical significance was defined as a P value <0.05.

Results

CONCENTRATIONS OF SERUM hCG, PROGESTERONE, miR-323-3p, miR-517a, miR-519d, AND miR-525-3p

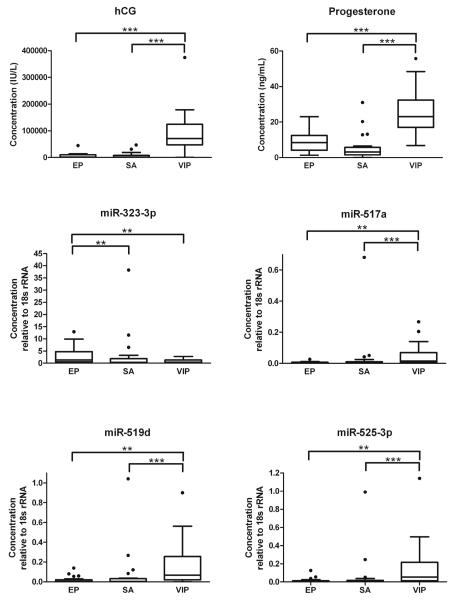

89 patients were included in the study, 27 patients with EP, 28 patients with SA, and 34 patients with VIP. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in maternal age or GA. Overall concentrations of hCG and progesterone were significantly higher in VIP compared to EP and SA groups (P<0.0001). Neither progesterone nor hCG showed significant differences between EP and SA. Thirty-one previously reported pregnancy-associated miRNAs (Supplementary Data Table 1) were initially screened by real-time PCR in order to identify candidate miRNAs that have the capability to discriminate EP and intrauterine pregnancy (IUP; data not shown). Four miRNAs, miR-323-3p, miR-517a, miR-519d and miR-525-3p, were confirmed to have significantly different serum concentrations in women with EP, SA, and VIP (Table 1). The serum concentrations of miR-517a, miR-519d, and miR-525-3p were significantly lower in EP and SA than in VIP. In contrast, women with EP had significantly increased serum concentrations of miR-323-3p over both SA and VIP, but there was no significant difference of miR-323-3p concentration between SA and VIP. miR-323-3p was the only marker tested in this study that showed significant difference between EP and SA (Table 1; Figure 1). Correlation between concentrations of serum markers and GA was performed in EP, SA, and VIP groups. Increased concentrations of hCG were significantly correlated with increased GA in VIP and SA (P<0.05 and P<0.01, respectively), and increased concentrations of miR-517a and miR-519d were significantly correlated with increased GA in VIP (P<0.05). In contrast, concentrations of hCG in EP, miR-517a and miR-519d in EP and SA, and progesterone, miR-323-3p, and miR-525-3p in EP, SA, and VIP showed no correlation with GA (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Patient age, GA, and serum concentrations of hCG, progesterone, and miRNAs in women with EP (n=27), SA (n=28), and VIP (n=34)

| EP (n=27) |

SA (n=28) |

VIP (n=34) |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Interquartile range) |

Median (Interquartile range) |

Median (Interquartile range) |

Kwallis* | EP vs SA* | EP vs VIP* | SA vs VIP* | |

| Patient age (years) |

25.8 (22.3-30.3) |

24.6 (20.7-30.9) |

22.9 (20.3-29.3) |

NS | NS | NS | NS |

| GA (weeks) |

7.0 (5.8-7.8) |

7.7 (5.9-8.5) |

7.0 (5.7-9.0) |

NS | NS | NS | NS |

| hCG (IU/L) |

1725.2 (231.6-10405.7) |

1537.0 (236.5-8049.1) |

71632.2 (47837.1-124537.7) |

<0.001 | NS | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Progesterone (ng/mL) | 8.5 (4.2-12.5) |

3.2 (1.5-5.8) |

23.1 (17.0-32.4) |

<0.001 | NS | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| miR-323-3p (Concentration relative to 18s) |

1.248 (0.525-4.752) |

0.327 (0-1.796) |

0.351 (0.022-1.244) |

<0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | NS |

| miR-517a (Concentration relative to 18s) |

0.003 (0.002-0.007) |

0 (0-0.010) |

0.014 (0.005- 0.070) |

<0.001 | NS | <0.01 | <0.001 |

| miR-519d (Concentration relative to 18s) |

0.005 (0-0.019) |

0.004 (0-0.032) |

0.066 (0.020- 0.256) |

<0.001 | NS | <0.01 | <0.001 |

| miR-525-3p (Concentration relative to 18s) |

0.003 (0-0.012) |

0 (0-0.017) |

0.052 (0.012- 0.215) |

<0.001 | NS | <0.01 | <0.001 |

Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn’s post hoc test.

Figure 1.

Box plot showing measurements of hCG, progesterone, miR-323-3p, miR-517a, miR-519d, and miR-525-3p in patients with EP, SA, and VIP (**, P<0.01 and ***, P<0.001, Dunn’s multiple comparison test).

Figure 2.

Graphs showing serum concentrations of hCG, progesterone, miR-323-3p, miR-517a, miR-519d, and miR-525-3p in patients with EP (open triangle, dashed line), SA (open square, dotted line), and VIP (open circle, solid line), respectively, at the GA of the ED visit.

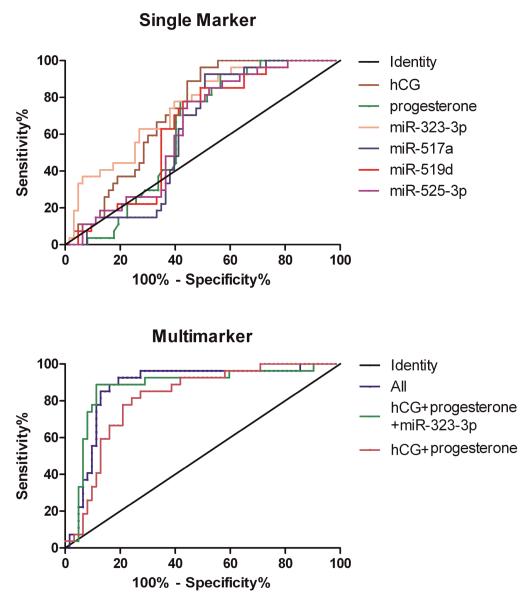

DIAGNOSTIC PERFORMANCE OF SERUM hCG, PROGESTERONE, miR-323-3p, miR-517a, miR-519d, AND miR-525-3p IN DIFFERENTIATING VIP, SA, AND EP

Table 2 presents the AUC of all single markers and various multimarker combinations. The ROC curves were constructed comparing serum measurements in patients with EP to patients with VIP and SA, which realistically represent performance of the tests in an ED setting. The sensitivities at the pre-defined specificities of 90% and 95% and specificities at the pre-defined sensitivities of 90% and 95% were calculated for all markers individually and in combination and are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Diagnostic accuracy of the single marker measurement of hCG, progesterone, miR-323-3p, miR-517a, miR-519d, and miR-525-3p, and the combination of multimarkers to predict EP in patients with abdominal pain/cramping and/or vaginal bleeding at pre-defined specificities and sensitivities

| AUC [lower and upper CI95%] |

90% Specificity |

95% Specificity |

90% Sensitivity |

95% Sensitivity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||

| hCG | 0.73 [0.63-0.83] | 14.8 | 11.1 | 51.6 | 51.6 |

| progesterone | 0.62 [0.51-0.73] | 3.7 | 0 | 43.6 | 33.9 |

| miR-323-3p | 0.73 [0.62-0.84] | 37.0 | 33.3 | 43.6 | 38.7 |

| miR-517a | 0.62 [0.50-0.73] | 11.1 | 0 | 50.0 | 35.5 |

| miR-519d | 0.64 [0.53-0.76] | 11.1 | 7.4 | 35.5 | 27.4 |

| miR-525-3p | 0.63 [0.52-0.75] | 11.1 | 0 | 37.1 | 30.7 |

| hCG+progesterone | 0.81 [0.72-0.91] | 33.3 | 7.4 | 58.1 | 41.9 |

| hCG+progesterone+ miR-323-3p | 0.87 [0.79-0.96] | 77.8b | 33.3a | 71.0 | 40.3 |

| hCG+progesterone+ miR-517a | 0.82 [0.73-0.91] | 29.6 | 11.1 | 46.8 | 46.8 |

| hCG+progesterone+ miR-519d | 0.82 [0.73-0.91] | 33.3 | 11.1 | 50.0 | 42.0 |

| hCG+progesterone+ miR-525-3p | 0.81 [0.72-0.90] | 26.0 | 11.1 | 48.4 | 40.3 |

| All | 0.88 [0.79-0.96] | 55.6 | 22.2 | 80.7a | 72.6b |

P<0.05

P<0.01 (AUC, sensitivities, and specificities of each combination of multimarkers were compared to that of hCG+progesterone (bold) in the same columns, respectively).

The diagnostic performance of single markers to detect EP was first evaluated, and the new markers were compared to hCG alone and progesterone alone. As single markers, both hCG and miR-323-3p had the highest AUC (Both 0.73; Table 2 and Figure 3A). At the fixed-specificities of 90% and 95%, miR-323-3p had the highest sensitivities of 37.0% and 33.3% for detecting EP, respectively. miR-323-3p demonstrated 22.2% greater sensitivity as compared to hCG alone and 33.3% greater sensitivity as compared to progesterone alone at both 90% and 95% specificities. These represented statistically significant gains in sensitivities over progesterone (P<0.001) but not hCG. All other miRNA markers had sensitivities below that of miR-323-3p when analyzed as single markers. Additionally, at the fixed-sensitivity of 90% and 95%, hCG had the highest single marker specificity of 51.6%.

Figure 3.

ROC analysis of serum hCG, progesterone, miR-323-3p, miR-517a, miR-519d, and miR-525-3p as single markers (A) and multimarkers (B) for prediction of EP.

To evaluate the value added by inclusion of the miRNAs, a multivariate logistic regression was conducted to determine the performance of different combinations of biomarkers compared to the dual marker analysis of hCG+progesterone as a standard reference. The AUCs of different multimarker combinations ranged from 0.81-0.88 for detecting EP, which were not significantly different from each other (Table 2 and Figure 3B). The combination of hCG+progesterone+miR-323-3p resulted in the highest sensitivities of 77.8% and 33.3%, which added 44.5% and 25.9% to the sensitivities of hCG+progesterone at the specificities of 90% and 95%, respectively (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively). The addition of other miRNAs to the combination of hCG+progesterone did not increase the sensitivity significantly. Furthermore, the addition of miR-323-3p to the dual marker combination of hCG+progesterone increased the specificity from 58.1% to 71.0% at a sensitivity of 90% but slightly reduced it from 41.9 to 40.3% at a sensitivity of 95%. Combining hCG, progesterone and all four miRNAs yielded the highest specificities of 80.7% and 72.6% at the sensitivities of 90% and 95%, respectively. Thus, the “all Marker” combination significantly increased specificities over the combination of hCG+progesterone (P<0.05 and P<0.01at sensitivities of 90% and 95%, respectively). However, the “all marker” sensitivities were decreased 22.2% and 11.1% compared to that of hCG+progesterone+miR-323-3p panel when specificities were fixed at 90% and 95% respectively.

A stepwise analysis was also performed to optimize sensitivity (Figure 4), which incorporated hCG cutoff ≤44,780 IU/L (the first step, 100% sensitivity and 45.2% specificity), progesterone ≤23ng/mL (the second step, 100% sensitivity and 50.0% specificity) and miR-323-3p ≥0.2 (the third step, 96.3% sensitivity and 72.6% specificity).

Figure 4.

A stepwise analysis using hCG, progesterone, and miR-323-3p to predict EP.

Discussion

Current diagnosis of EP relies on the combination of sonography and serial hCG measurements in women with suspicious clinical symptoms (28). Life-threatening risks are associated with this approach as women may experience tubal rupture while waiting 48 hours for the second hCG measurement. There is a great need for new markers and new algorithms with high sensitivity and specificity to permit earlier diagnosis and proper management of EP.

Over 20 serum biomarkers have been investigated to date in an attempt to allow earlier and more accurate diagnosis of EP. However, at present, their clinical utility is very limited (28). At least two intrinsic properties of some of these markers limit their use. First, their serum concentrations often change with GA. Second, a number of markers can discriminate the EP from VIP, but are unable to distinguish EP from SA (28). An ideal marker would be one that remains steady throughout pregnancy and is capable of discriminating EP from both SA and VIP. In the current study, miR-323-3p and miR-525-3p demonstrated steady serum concentrations across GA, whereas the concentrations of miR-517a and miR-519d increase with GA in normal pregnancy. These findings agree with previous studies that have demonstrated no GA-dependent changes in serum miR-323-3p concentrations between first and third trimesters; in contrast, the concentration of circulating miR-517a showed a GA dependence as pregnancy progressed into the third trimester (11). Furthermore, miR-323-3p differentiated itself from all other markers tested in the current study by showing significantly higher serum concentrations in EP than that in both SA and VIP. These characteristics of miR-323-3p fulfill the above criteria for the selection of a potential improved marker for detection of EP.

The single marker results for hCG and progesterone and the dual marker results for hCG+progesterone obtained here were similar to previously published studies (29, 30), indicating that these measurements are insufficient to diagnose EP. Nevertheless, when evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of new biomarkers for detection of EP, the sensitivity and specificity of any single or multiple serum biomarker panel would need to be significantly higher than that achieved by serum hCG alone, progesterone alone, and hCG+progesterone dual marker panel in order to be incorporated into a diagnostic algorithm.

When considered as a single biomarker, miR-323-3p presented the highest sensitivity, 37% at 90% specificity, which was significantly higher than that of progesterone alone and also improved the sensitivity over that of hCG. However, this sensitivity of miR-323-3p as a single biomarker is not sufficient to be of clinical value. In addition, using any of the candidate miRNAs as single serum biomarkers yielded limited specificity. As no stand-alone markers for EP have been consistently demonstrated to have superior diagnostic performance, including the markers examined in this study, using multiple serum marker analysis might be a possible solution for the diagnosis of EP. Combination of hCG+progesterone+miR-323-3p significantly improved diagnostic utility, showing the highest sensitivity among all the multimarker panels using multivariate logistic regression analyses. Furthermore, the combination of hCG+progesterone+miR-323-3p also improved specificity, although the addition of other miRNA markers was necessary to achieve the highest specificity and statistical significance. However, addition of all miRNAs reduced the sensitivity compared to that achieved by the combination of hCG+progesterone+miR-323-3p. The maximum specificity gained by adding the other miRNAs to hCG+progesterone+ miR-323-3p could be due to the different diagnostic abilities of these miRNA markers. It could also be limited by the small number of patients analyzed in this study. A significant improvement of specificity without compromising the optimal sensitivity using the combination of hCG+progesterone+ miR-323-3p may be achieved by increasing the patient sample size. The alternative strategy is to use the stepwise analysis optimizing sensitivity, which incorporated hCG, progesterone and miR-323-3p and achieved sensitivity of 96.3% and specificity of 72.6%. These observations suggest that miR-323-3p may be useful to improve the diagnostic performance in multiple marker panel designed for the early detection of EP.

Multimarker approaches for the diagnosis of EP have been examined in previous studies. Most recently, Rausch et al. evaluated a large number of biomarkers and developed multimarker algorithm combining four markers (progesterone, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), inhibin A, and activin A) that demonstrated improved diagnostic utility (31). However, that study did not evaluate the algorithm in a patient population that included SA. Our study more accurately reflects the diagnostic utility of the biomarkers in an ED setting by including patients with not only EP and VIP, but also SA.

miRNA-323-3p, miRNA-517a, miRNA-519d, and miRNA-525-3p are pregnancy-associated miRNAs in maternal circulation during pregnancy that are rapidly cleared from maternal circulation after delivery (11). It was originally proposed that nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) of placental origin are released into the maternal circulation in the form of apoptotic bodies (32). Luo et al. recently demonstrated that miRNAs are exported from human placental syncytiotrophoblasts into maternal circulation via exosomes and suggested that circulating trophoblast-derived miRNAs reflect the physiological status of the pregnancy and could be used diagnostically (10). Although the fundamental mechanisms that underlie miRNA physiology and their contribution to the clinical manifestation of EP are not completely understood, and the systemic targets of circulating pregnancy-associated miRNAs remains unknown, it is now clear that miRNAs are released into the circulation and their concentrations likely reflect tissue physiologic or pathologic states (21, 33). Recent studies have demonstrated that fetal growth restriction is associated with increased total concentrations of a set of trophoblastic miRNAs in maternal circulation, highlighting the need to explore circulating miRNAs as potential biomarkers for pregnancy-related diseases (20).

miR-323-3p is clustered on 14q32.31 and miRNA-517a, miRNA-519d, and miRNA-525-3p are clustered on 19q13.42, which are critical regions for placental growth and embryonic development (11). In the case of tubal EP, trophoblasts invade and erode the tubal muscular wall, and maternal blood vessels are opened (34). During this process, it is possible that the miRNAs are released into maternal circulation, as seen in the present study. The down regulation of all three chromosome 19 miRNA cluster miRNAs, miRNA-517a, miRNA-519d, and miRNA-525-3p, in both SA and EP may reflect abnormal embryo/trophoblast growth. In contrast, miR-323-3p was the only marker tested in the current study whose serum concentrations were increased in EP. Other serum components tend to be increased in EP, such as creatine kinase and VEGF which may be released from the damaged fallopian tube, and various cytokines which may be associated with peritoneal irritation. It is possible that the tissue-origin of the circulating miR-323-3p in EP patients is not restricted to trophoblast as suggested by Miura et al (11). Consequently, the increased serum concentration of this miRNA may be the result of tubal damage, tubal implantation or peritoneal inflammation. Obviously, this hypothesis warrants further investigation.

This proof-of concept study is the first to examine the relationship between pregnancy-associated miRNAs and early pregnancy outcomes, and the first to explore the diagnostic value of miRNAs for EP. As miRNA molecules are highly stable in circulation, they are more robust and suitable to serve as blood-based biomarkers than some of the protein- or peptide-based markers. However, there are several limitations of this study. First, the development of miRNAs as non-invasive diagnostic markers is at its infancy stage. miRNA assays are not routinely used in clinical practice and no universally accepted standard procedure exists at the present time. However, recent reports suggest that miRNAs may serve as improved markers for numerous diseases, including: cancer, autoimmune diseases, sepsis, acute myocardial infarction, and others (6). It appears promising that manufacturers will develop faster and cheaper miRNA assays suitable for the clinical use in the near future. Second, increased variances were seen in the test characteristic estimates, in part due to a relatively small sample size within any given patient group. A larger, randomized study is needed to validate this multimarker strategy.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Data Table 1. The sequences for the primers and probes.

Nonstandard abbreviations

- EP

ectopic pregnancy

- ED

emergency department

- HCG

human chorionic gonadotropin

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- ACOG

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- VIP

viable intrauterine pregnancy

- SA

spontaneous abortion

- miRNAs

microRNAs

- GA

gestational age

- Ct

threshold cycle

- AUC

area under the curve

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- IUP

intrauterine pregnancy

References

- 1.Murray H, Baakdah H, Bardell T, Tulandi T. Diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Cmaj. 2005;173:905–12. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farquhar CM. Ectopic pregnancy. Lancet. 2005;366:583–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaunik A, Kulp J, Appleby DH, Sammel MD, Barnhart KT. Utility of dilation and curettage in the diagnosis of pregnancy of unknown location. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:130.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipscomb G. Diagnosis and monitoring of ectopic and abnormal pregnancies, in handbook. In: Gronowski A, editor. Handbook of clinical laboratory testing during pregnancy. Humana Press; Totowa, New Jersey: 2004. Vol. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 94: Medical management of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1479–85. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817d201e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scholer N, Langer C, Dohner H, Buske C, Kuchenbauer F. Serum microRNAs as a novel class of biomarkers: a comprehensive review of the literature. Experimental hematology. 2010;38:1126–30. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroh EM, Parkin RK, Mitchell PS, Tewari M. Analysis of circulating microRNA biomarkers in plasma and serum using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) Methods (San Diego, Calif ) 2010;50:298–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:10513–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chim SSC, Shing TKF, Hung ECW, Leung T-Y, Lau T-K, Chiu RWK, Lo YMD. Detection and characterization of placental microRNAs in maternal plasma. Clin Chem. 2008;54:482–90. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.097972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo S-S, Ishibashi O, Ishikawa G, Ishikawa T, Katayama A, Mishima T, et al. Human villous trophoblasts express and secrete placenta-specific microRNAs into maternal circulation via exosomes. Biology of reproduction. 2009;81:717–29. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.075481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miura K, Miura S, Yamasaki K, Higashijima A, Kinoshita A, Yoshiura K-i, Masuzaki H. Identification of pregnancy-associated microRNAs in maternal plasma. Clin Chem. 2010;56:1767–71. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.147660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotlabova K, Doucha J, Hromadnikova I. Placental-specific microRNA in maternal circulation--identification of appropriate pregnancy-associated microRNAs with diagnostic potential. Journal of reproductive immunology. 2011;89:185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu Y, Li P, Hao S, Liu L, Zhao J, Hou Y. Differential expression of microRNAs in the placentae of Chinese patients with severe pre-eclampsia. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine : CCLM / FESCC. 2009;47:923–9. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2009.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Diao Z, Su L, Sun H, Li R, Cui H, Hu Y. MicroRNA-155 contributes to preeclampsia by down-regulating CYR61. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:466.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pineles BL, Romero R, Montenegro D, Tarca AL, Han YM, Kim YM, et al. Distinct subsets of microRNAs are expressed differentially in the human placentas of patients with preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:261.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu X-m, Han T, Sargent IL, Yin G-w, Yao Y-q. Differential expression profile of microRNAs in human placentas from preeclamptic pregnancies vs normal pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:661.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montenegro D, Romero R, Kim SS, Tarca AL, Draghici S, Kusanovic JP, et al. Expression patterns of microRNAs in the chorioamniotic membranes: a role for microRNAs in human pregnancy and parturition. The Journal of pathology. 2009;217:113–21. doi: 10.1002/path.2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avissar-Whiting M, Veiga KR, Uhl KM, Maccani MA, Gagne LA, Moen EL, Marsit CJ. Bisphenol A exposure leads to specific microRNA alterations in placental cells. Reproductive toxicology (Elmsford, N Y ) 2010;29:401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maccani MA, Avissar-Whiting M, Banister CE, McGonnigal B, Padbury JF, Marsit CJ. Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy is associated with downregulation of miR-16, miR-21, and miR-146a in the placenta. Epigenetics : official journal of the DNA Methylation Society. 2010;5:583–9. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.7.12762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mouillet JF, Chu T, Hubel CA, Nelson DM, Parks WT, Sadovsky Y. The levels of hypoxia-regulated microRNAs in plasma of pregnant women with fetal growth restriction. Placenta. 2010;31:781–4. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mouillet J-F, Chu T, Sadovsky Y. Expression patterns of placental microRNAs. Birth defects research Part A, Clinical and molecular teratology. 2011;91:737–43. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warrick J, Gronowski AM, Zhao Q, Moffett C, Bishop E, Woodworth A. Serum Activin A does not predict ectopic pregnancy as a single measurement test, alone or as part of a multi-marker panel including progesterone and hCG. Clinica Chimica Acta accepted. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moltzahn F, Olshen AB, Baehner L, Peek A, Fong L, Stoppler H, et al. Microfluidic-based multiplex qRT-PCR identifies diagnostic and prognostic microRNA signatures in the sera of prostate cancer patients. Cancer research. 2010;71:550–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang F, Hajkova P, Barton SC, Lao K, Surani MA. MicroRNA expression profiling of single whole embryonic stem cells. Nucleic acids research. 2006;34:e9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnj009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia JR, Krause A, Schulz S, Rodriguez-Jimenez FJ, Kluver E, Adermann K, et al. Human beta-defensin 4: a novel inducible peptide with a specific salt-sensitive spectrum of antimicrobial activity. The FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2001;15:1819–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayor-Lynn K, Toloubeydokhti T, Cruz AC, Chegini N. Expression profile of microRNAs and mRNAs in human placentas from pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia and preterm labor. Reproductive sciences (Thousand Oaks, Calif ) 2010;18:46–56. doi: 10.1177/1933719110374115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore RG, Brown AK, Miller MC, Skates S, Allard WJ, Verch T, et al. The use of multiple novel tumor biomarkers for the detection of ovarian carcinoma in patients with a pelvic mass. Gynecologic oncology. 2008;108:402–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cartwright J, Duncan WC, Critchley HOD, Horne AW. Serum biomarkers of tubal ectopic pregnancy: current candidates and future possibilities. Reproduction (Cambridge, England) 2009;138:9–22. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ledger WL, Sweeting VM, Chatterjee S. Rapid diagnosis of early ectopic pregnancy in an emergency gynaecology service--are measurements of progesterone, intact and free beta human chorionic gonadotrophin helpful? Hum Reprod. 1994;9:157–60. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borrelli PTA, Butler SA, Docherty SM, Staite EM, Borrelli AL, Iles RK. Human chorionic gonadotropin isoforms in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Clin Chem. 2003;49:2045–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.022095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rausch ME, Sammel MD, Takacs P, Chung K, Shaunik A, Barnhart KT. Development of a multiple marker test for ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:573–82. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820b3c61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishihara N, Matsuo H, Murakoshi H, Laoag-Fernandez JB, Samoto T, Maruo T. Increased apoptosis in the syncytiotrophoblast in human term placentas complicated by either preeclampsia or intrauterine growth retardation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:158–66. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.119176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wittmann J, Jack H-M. Serum microRNAs as powerful cancer biomarkers. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2010;1806:200–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kokawa K, Shikone T, Nakano R. Apoptosis in human chorionic villi and decidua in normal and ectopic pregnancy. Molecular human reproduction. 1998;4:87–91. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Data Table 1. The sequences for the primers and probes.