Abstract

Focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a major cause of end-stage kidney disease. Recent advances in molecular genetics show that defects in the podocyte play a major role in its pathogenesis and mutations in inverted formin 2 (INF2) cause autosomal dominant FSGS. In order to delineate the role of INF2 mutations in familial and sporadic FSGS, we sought to identify variants in a large cohort of patients with FSGS. A secondary objective was to define an approach for genetic screening in families with autosomal dominant disease. A total of 248 individuals were identified with FSGS, of whom 31 had idiopathic disease. The remaining patients clustered into 64 families encompassing 15 from autosomal recessive and 49 from autosomal dominant kindreds. There were missense mutations in 8 of the 49 families with autosomal dominant disease. Three of the detected variants were novel and all mutations were confined to exon 4 of INF2, a regulatory region responsible for 90% of all changes reported in FSGS due to INF2 mutations. Thus, in our series, INF2 mutations were responsible for 16% of all cases of autosomal dominant FSGS, with these mutations clustered in exon 4. Hence, screening for these mutations may represent a rapid, non-invasive and cost-effective method for the diagnosis of autosomal dominant FSGS.

Introduction

Focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a common cause of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) worldwide. It is a clinicopathological entity that is characterized by nephrotic syndrome, rapid progression to ESKD, and pathological changes of focal glomerulosclerosis on light microscopy, as well as effacement of foot processes on electron microscopy.1 The etiology and pathogenesis of FSGS is not completely known; however, recent advances in molecular genetics and molecular biology provide insight into its pathogenesis. It is now known that FSGS is a defect of the glomerular filtration barrier (GFB). The GFB is made up of the podocyte and its slit diaphragm, the glomerular basement membrane, and specialized fenestrated endothelium. Disruption of the GFB leads to loss of permselectivity and proteinuria. The podocyte and its slit diaphragm have a central role in maintaining the structural and functional integrity of the GFB. Evidence for this is the development of nephrotic syndrome when genes encoding the podocyte slit diaphragm and podocyte cytoskeletal proteins are mutated.2–7

Mutations in inverted formin 2 (INF2) were recently reported as a cause of autosomal dominant (AD) FSGS.8 Formin is one of the proteins that promote nucleation of actin, a rate-limiting step in actin polymerization.9 INF2 is widely expressed in the kidney, especially in the podocytes and tubules; it is also expressed in other organs such as the liver, heart, placenta, and skeletal muscle.8 Transfection experiments revealed that three of the reported mutations (E184K, S186P, and R218Q) caused mislocalization of the protein in undifferentiated cultured human podocytes, suggesting that the mutations may cause FSGS by dysregulation of the podocyte cytoskeleton.8 Most of the mutations reported thus far in INF2 cluster in exon 4, a region of the gene that encodes for the N-terminal regulatory region of the protein.8–10 The prevalence of INF2 mutations in subjects with familial and sporadic FSGS is unknown. In addition, the phenotype associated with it has not been fully defined.

The main objective of this report is to determine the frequency of INF2 mutations in a large cohort of patients with sporadic and familial FSGS, and also describe the phenotype associated with it.

Results

Clinical data

We identified 217 individuals with FSGS from 64 families, and 31 individuals with idiopathic FSGS. In all, 15 (15.8%) families had two or more affected individuals in one generation and they were classified as having presumed autosomal recessive (AR) disease, and 49 (51.6%) had two or more affected individuals in at least two generations and thus were classified as having presumed AD disease. The racial distribution, age at onset of disease, and age at ESKD in the three groups are shown in (Table 1). The subjects in the idiopathic group had early-onset disease as compared with the AR and AD data set (Kruskal–Wallis test; P=0.005), but there was no difference in age at onset of ESKD. There are proportionately more African Americans in the idiopathic group as compared with the AR and AD groups (38.7% vs. 20% vs. 28.6%); the difference was not statistically significant (χ2, P=0.6). In all, 6 individuals in the idiopathic group are known to have had kidney transplant, as well as 6 individuals in the AR group and 22 individuals in the AD assemblage. The recurrence rate of FSGS in renal allograft is higher in the idiopathic group as compared with the AR and AD groups.

Table 1.

Demographics of individuals and families with idiopathic and hereditary FSGS

| Parameters | Idiopathic (n=31) | AR (n=15) | AD (n=49) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 51.6 | 73.3 | 59.2 |

| African American | 38.7 | 20.0 | 28.6 |

| Others | 9.7 | 6.7 | 12.2 |

| Age onset median (range) yrs | 9.0 (1.5–45) | 21 (2.5–49) | 24.5 (1–66)* |

| Median (range) proteinuria (g) | 3.75 (3–20) | 3 (2.4–20) | 5 (1–20) |

| Age ESKD median (range) yrs | 32 (8–45) | 29.5 (6–50) | 40 (8–63) |

| Transplant | 6 | 7 | 22 |

| Transplant recurrence | 1/6 (16.7) | 0/7 (0%) | 2/22 (9.1%) |

P=0.005,

AR: Autosomal recessive; AD: Autosomal dominant

INF2 Screening

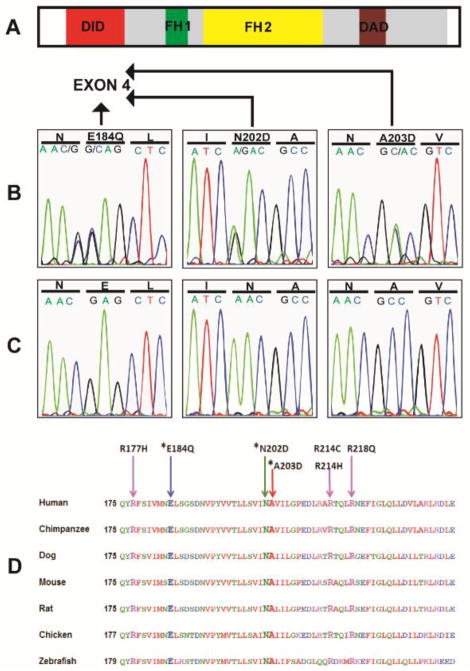

We found variants in eight (8.4%) of the kindreds examined. All of the variants were found in the AD group. All of the variants caused nonconservative changes in highly conserved amino acids and are clustered in exon 4 of INF2. Three of the nonconservative changes reported in the present study have not been previously reported. All of the newly identified variants segregate with disease in the families. In addition, seven individuals who were asymptomatic at the time of ascertainment were also found to carry these changes. Table 2 shows the clinical characteristics of families with mutations in INF2. None of the changes were identified in 192 control chromosomes or in the 1000 Genomes catalog of human genetic variations. The three new variants found in this study are shown in (Figure 1). All of the changes are highly conserved in evolution down to zebrafish (Figure 1). In addition, all of the changes had a Naive Bayes posterior probability of >99% of being functionally damaging when modeled in silico11 (Table 3). The list of INF2 mutations reported so far in the literature, including this study, is shown in Table 4. Supplementary Table S1 online shows known and new INF2 variants and single-nucleotide polymorphisms identified in this study.

Table 2.

Clinical Phenotype of 8 families with FSGS and mutations in INF2

| Individual Number | Race/ Country | Mutation | Age onset (years) | Symptomatic Individuals# | Histology | Median age at ESKD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6502 | C/USA | Exon 4 608C>A A203D* | 14–24 | 2/2 | FSGS | 42 |

| 6505 | C/USA | Exon 4 550G>C E184Q* | 20–37 | 8/8 | FSGS | 33 |

| 6507 | C/USA | Exon 4 530G>A R177H | 28–34 | 2/4 | FSGS | 36 |

| 6515 | C/Canada | Exon 4 653G>A R218Q | 16–46 | 2/3 | FSGS | U |

| 6518 | C/New Zealand | Exon 4 605A>G N202D* | 19–24 | 2/2 | FSGS | U |

| 6529 | C/Belgium | Exon 4 641G>A R214H | 22–45 | 6/6 | FSGS | 45.5 |

| 6556 | C/United Kingdom | Exon 4 641G>A R214H | 27–30 | 3/5 | FSGS | 40 |

| 6635 | H/Uruguay | Exon 4 641C>T R214C | 20 | 1/3 | FSGS | U |

New mutations in this study

C: Caucasian; H: Hispanic; U: Unknown

Numerator: number of individuals with FSGS, nephrotic syndrome or chronic kidney disease in the family. Denominator: number of individuals with the mutation.

Figure 1.

New INF2 mutations in familial FSGS. (A) Protein domains of INF2. (B) The three new mutations detected in families with FSGS. The new mutations (E184Q, N202D, and A203D) are all missense mutations in exon 4 of the gene which encode for the diaphanous inhibitory domain (DID) of the protein. Note that the new variant N183K identified in this study is not conserved in evolution and is therefore not likely to be disease causing. (C) Normal sequences (D) The three new mutations and the other four mutations identified in this cohort are well conserved in evolution down to the zebra fish. *Denotes new mutations.

Table 3.

In silico prediction of effect of variants

| Mutations | Predicted effect | HumVar-Polyphen score |

|---|---|---|

| Exon4 608C>A, A203D* | Probably damaging | 0.997 |

| Exon4 550G>C, E184Q* | Probably damaging | 0.995 |

| Exon4 530G>A, R177H | Probably damaging | 0.997 |

| Exon4 653G>A, R218Q | Probably damaging | 0.996 |

| Exon4 605A>G, N202D* | Probably damaging | 0.992 |

| Exon4 641G>A, R214H | Probably damaging | 0.997 |

| Exon4 641C>T, R214C | Probably damaging | 0.997 |

New mutations in this study

Table 4.

Scope of INF2 mutations in familial FSGS

| Mutation | Exon | Ancestry | Number of families with change | Age of onset (years) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A13T | 2 | European | 1 | 21 | 8 |

| L42P | 2 | European | 1 | 11–13 | 8 |

| L76P | 2 | European | 1 | 27–44 | 13 |

| R177H | 4 | European | 3 | 19–34 | 13 and present study |

| E184K | 4 | African American | 1 | 17–30 | 8 |

| E184Q | 4 | European | 1 | 20–37 | Present study |

| S186P | 4 | European | 2 | 12–67 | 8 |

| Y193H | 4 | Middle East | 1 | 24 | 13 |

| L198R | 4 | European/North Africa | 2 | 13–36 | 8 and 13 |

| N202D | 4 | European | 1 | 19–24 | Present study |

| A203D | 4 | European | 1 | 14–24 | Present study |

| R214C | 4 | European/Hispanic | 3 | 5–44 | 13 and present study |

| R214H | 4 | European | 4 | 12–72 | 8 and present study |

| R218Q | 4 | European | 4 | 10–46 | 8, 13 and present study |

| R218W | 4 | African American | 1 | 27–33 | 8 |

| E220K | 4 | European/Korean | 3 | 7–30 | 8, 10, 13 |

Genotype/Phenotype correlation

All eight families with INF2 mutations were of European descent, including seven Caucasian families and a single Hispanic family, also likely to be of European descent (Table 2). In the subset of AD families without mutations in INF2, 51.2% were Caucasian. There was no difference in age at onset, degree of proteinuria, age at ESKD between groups of AD subjects with and without mutations in INF2. There was also no significant difference in the rate of FSGS recurrence after renal transplantation between these groups (1/3 vs. 1/19, respectively). In all, 7 of 33 individuals carried an INF2 mutation but were not symptomatic, indicating either reduced penetrance or that they had yet to demonstrate signs of the disease.

Renal Pathology in INF2 mutations and modeling of INF2 variants

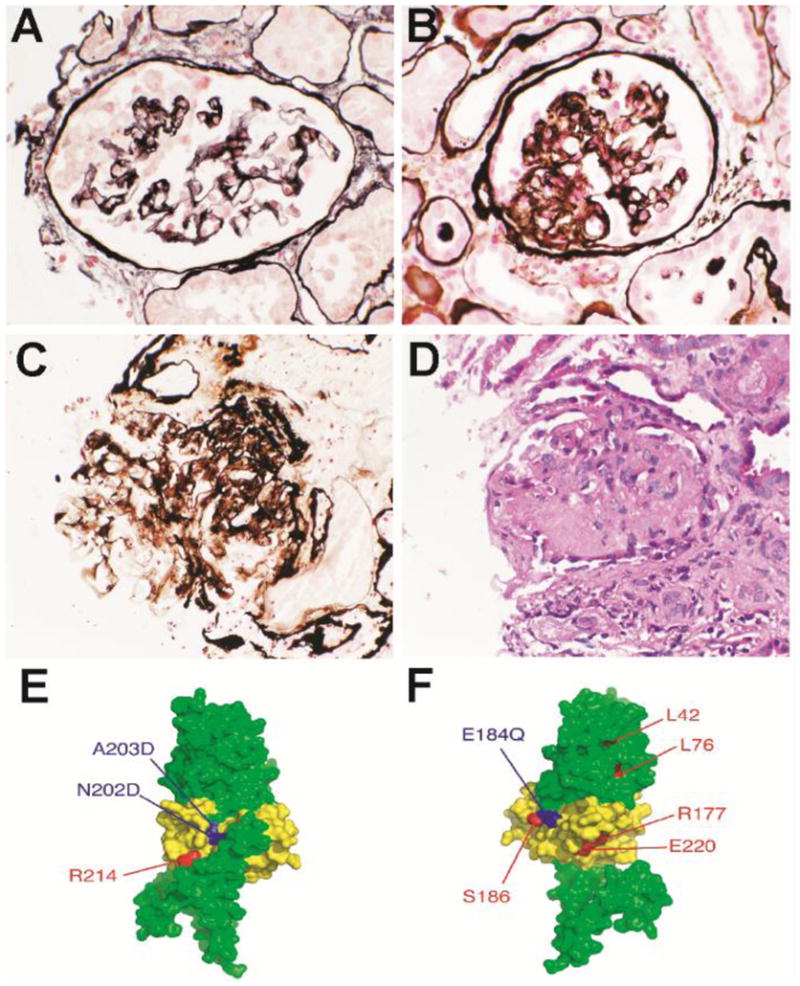

Light microscopy of renal biopsies from two individuals with R177H and A203D showed segmental sclerosis with adhesions to Bowman’s capsule (Figure 2a–2d). The biopsy from the individual with the R177H variant showed collapsing appearance in some glomeruli (Figure 2a and b). Mesangial staining for IgM and C3 was identified by immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy showed patchy epithelial foot process effacement. Figure 2e and f shows three-dimensional modeling of INF2 diaphanous inhibitory domain (DID) based on the structure of mDia1. New variants identified in this study mapped to the human INF2 homolog of critical mouse mDia1 IQGAP1-interacting DID subdomain. In addition, residues N202 and A203 model to the protein surface next to I152, a residue identified as important for direct interaction with diaphanous autoregulatory domain (DAD).8,12,13

Figure 2.

Renal biopsy in INF2 mutation and location of INF2 mutations in three dimensional modeling of INF2 DID based on structure of mDia1

Light microscopy of renal biopsies from two individuals with R177H and A203D showed segmental sclerosis with adhesions to Bowman’s capsule (Figures 2A–D). The biopsy from the individual with the R177H variant showed collapsing appearance in some glomeruli (Figures 2A and 2B). A model of human INF2 amino acids 1–330 was constructed using the Phyre threading server and the mDia1 structure (Figures 2E–F) (20). The region corresponding to the mDia1 IQGAP1 interacting DID subdomain (INF2 amino acids 149 through 238) is colored yellow13,21. New mutations identified in the present study are shown in blue, mutations identified in previous studies are shown in red8,13. (E) Global front view of the INF2 model. Residues N202 and A203 model to the protein surface next to I152, a residue identified as important for direct interaction with DAD (8, 13). (F) Global rear view of the INF2 model. Residue E184 maps to the surface of the protein and is adjacent to the previously identified mutation in S186.

Discussion

Familial cases of FSGS are responsible for ~1% of all cases of FSGS. However, previous studies of this subgroup have illuminated our understanding of the pathogenesis of FSGS. Mutations in INF2 were recently reported as a cause of FSGS.8 In this study, we performed mutation analysis of INF2 in a large cohort of patients with familial and idiopathic FSGS. We found mutations in INF2 in 16.3% of the families with presumed AD FSGS and no mutations in individuals with idiopathic disease or those with AR disease. We cannot completely exclude a role for INF2 mutations in the etiology of idiopathic and AR FSGS because of our limited sample size. In addition, the difference in clinical characteristics between idiopathic, AR, and AD FSGS should be interpreted with caution, as this study is not population based; the differences observed in the three groups may be due to selection bias. Genetic mutations known to cause nephrotic syndrome and FSGS have previously been excluded in these families.14 The present study, in conjunction with the initial report by Brown et al., and a recent study from France, suggest that mutation in INF2 is the most common cause of AD FSGS.8,13

INF2 is a member of the formin family. Formin is one of the three proteins that promote nucleation of actin, a rate-limiting step in actin polymerization.9 The domain structure, which is similar to the diaphanous formins, comprises formin homology 1 and 2 domains (FH1 and FH2), DID, and DAD.15 However, unlike the diaphanous formins, INF2 is capable of enabling both actin polymerization and depolymerization.15 The depolymerization activity is regulated by the interaction between the DID and the DAD domains.15–16 This step is inhibited by the binding of GTPase RhoA to the N-terminal element DID. RhoA is able to facilitate this because the binding site on DID partially overlaps with DAD; in addition, RhoA facilitates auto-inhibition.12,17

We found three new mutations in this series, thereby increasing the number of INF2 mutations reported as a cause of FSGS to 16.8,10,13 The changes reported in this study and previous studies are conserved in evolution and are absent from public single-nucleotide polymorphism databases, as well as from the 1000 Genomes Project. Exon 4 contains all of the disease-causing variants in the present study. When combined with previous studies, 30 families with FSGS have been reported to have INF2 mutations and 27/30 (90%) have mutations in exon 4, whereas the remaining have mutations in exon 2 of INF2. Exon 4 therefore appears to be a critical region for mutations in this gene; in addition, it encodes the DID domain of the protein that is responsible for auto-regulation of INF2 function. Most of the variants reported in this series have been shown to cause mislocalization of INF2 in podocyte culture and some of them also inhibit the interaction between INF2-DID and mDias-DAD, suggesting that the changes are functionally important for regulation of the actin cytoskeleton.8,17

There was wide variability in the clinical expression of disease due to INF2 mutations. At the time of ascertainment, 7/33 individuals with INF2 mutations in this study were known to be asymptomatic; three of these seven individuals were in the age group of 45 to 73 years, whereas the other four were less than 30 years of age. This is consistent with incomplete penetrance that is often seen in AD disease. It is possible that young subjects may develop FSGS with advancing age. An alternative explanation may be that there are yet-to-be identified genetic modifiers and environmental factors that may explain this variable clinical expression.

The clinical implications of these findings reveal that there may be a rationale for screening for mutations in exon 4 and exon 2 of INF2 in presumed AD FSGS. We did not find mutations in any of the other known FSGS genes (NPHS2, ACTN4, TRPC6, CD2AP, and PLCE1) in about 92% of the families studied, confirming that FSGS is genetically heterogeneous and also suggesting the existence of other disease-causing genes.18 With advances in genomics, such as whole-exome and genome sequencing, other genetic causes of FSGS will be identified and this will hopefully lead to a better understanding of the disease pathogenesis and rapid and noninvasive diagnosis of both the sporadic and familial forms of the disease.

In conclusion, INF2 mutations are responsible for 16% of all cases of AD FSGS in this series and, as reported, 90% of the mutations are clustered in exon 4, a regulatory region of the gene. Screening for mutations in exon 4 and exon 2 of INF2 may represent a rapid, noninvasive, and cost-effective method for the diagnosis of AD FSGS.

Subjects and Methods

Clinical data

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Duke University Medical Center (Durham, NC). Methods of subject recruitment have been previously reported.19 Inclusion criteria are as follows: (1) diagnosis of biopsy-proven FSGS; (2) exclusion of secondary causes of FSGS such as HIV infection, hepatitis, and obesity; and (3) exclusion of mutations in known FSGS/nephrotic syndrome genes. Clinical data obtained included a complete family history, including other associated morbidities, age at onset of disease, and age at ESKD, as well as history of kidney transplantation and recurrence in the renal allograft. Albuminuria and serum creatinine were measured using standard methods.

Mutational analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using the Qaigen/Puregene kit (Qaigen, Hilden, Germany). Mutational analysis was carried out by sequencing of both strands of all exons of INF2 using exon-flanking primers; primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S2 online. All sequences were analyzed with the Sequencher software (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI).

In silico prediction of impact of amino acid substitution

All new non-synonymous variations were individually entered into PolyPhen 2 software (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/index.shtml) to examine the predicted damaging effect of the amino-acid substitution to the function of inverted formin 2 isoform 1 (Uniprot ID: Q27J81). The HumVar-trained version was used, which is optimal for Mendelian disorders as it distinguishes mutations with drastic effects from all the remaining human variation, including abundant mildly deleterious alleles. PolyPhen 2 calculates a Naive Bayes posterior probability that any mutation is damaging and this is represented with a score ranging from 0 to 1. A mutation was also appraised qualitatively as benign, possibly damaging, or probably damaging based on the model’s false-positive rate.11

Three dimensional modeling of INF2 DID based on structure of mDia1

The location and functional significance of new mutations in this study were tested by designing a model of the human INF2 amino acids 1–330 using the Phyre threading program.8,20 Models and location of the mutated residues were predicted using PyMol (PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA).

Data analysis

The clinical data and frequency of mutations in INF2 were compared between the single- and multigeneration families. All categorical data were compared by means of χ2-test and continuous variables by Student’s t-test if they were normally distributed, and Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous data that are not normally distributed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Duke MedScholars Award to MPW. NIH K08DK082495-01 and grants from Nephcure foundation to RG. RG is a recipient of a Doris Duke Clinical Scientist Development Award. We would like to thank the personnel of the Center for Human Genetics core facilities and most importantly the family members of the Duke FSGS project.

Footnotes

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

References

- 1.Churg J, Habib R, White RH. Pathology of the nephrotic syndrome in children: a report for the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children. Lancet. 1970;760:1299–1302. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(70)91905-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kestila M, Lenkkeri U, Mannikko M, et al. Positionally cloned gene for a novel glomerular protein-nephrin- is mutated in congenital nephrotic syndrome. Mol Cell. 1998;1:575–582. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boute N, Gribouval O, Roselli S, et al. NPHS2, encoding the glomerular protein podocin, is mutated in autosomal recessive steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Nat Genet. 2000;24:349–354. doi: 10.1038/74166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan JM, Kim SH, North KN, et al. Mutations in ACTN4, encoding alpha-actinin-4, cause familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet. 2000;24:251–256. doi: 10.1038/73456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winn MP, Conlon PJ, Lynn KL, et al. A mutation in the TRPC6 cation channel causes familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Science. 2005;308:1801–1804. doi: 10.1126/science.1106215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JM, Wu H, Green G, et al. CD2-associated protein haploinsufficiency is linked to glomerular disease susceptibility. Science. 2003;300:1298–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.1081068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinkes BG, Wiggins RC, Gbadegesin RA, et al. Positional cloning uncovers mutations in PLCE1 responsible for a nephrotic syndrome variant that may be reversible. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1397–1405. doi: 10.1038/ng1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown EJ, Schlöndorff JS, Becker DJ, et al. Mutations in the formin gene INF2 cause focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:72–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faix J, Grosse R. Staying in shape with formins. Dev Cell. 2006;10:693–706. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee HK, Han KH, Jung YH, et al. Variable renal phenotype in a family with an INF2 mutation. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:73–76. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1644-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sunyaev S, Ramensky V, Koch I, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:591–7. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otomo T, Otomo C, Tomchick DR, et al. Structural basis of Rho GTPase-mediated activation of the formin mDia1. Mol Cell. 2005;18:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyer O, Benoit G, Gribouval O, et al. Mutations in INF2 Are a Major Cause of Autosomal Dominant Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gbadegesin R, Bartkowiak B, Lavin PJ, et al. Exclusion of homozygous PLCE1 (NPHS3) mutations in 69families with idiopathic and hereditary FSGS. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:281–285. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-1025-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chhabra ES, Higgs HN. INF2 Is a WASP homology 2 motif-containing formin that severs actin filaments and accelerates both polymerization and depolymerization. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26754–26767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604666200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chhabra ES, Ramabhadran V, Gerber SA, et al. INF2 is an endoplasmic reticulum-associated formin protein. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1430–1440. doi: 10.1242/jcs.040691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun H, Schlondorff JS, Brown EJ, et al. Rho activation of mDia formins is modulated by an interaction with inverted formin 2 (INF2) Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017010108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gbadegesin R, Lavin P, Janssens L, et al. A new locus for familial FSGS on chromosome 2p. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1390–1397. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009101046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winn MP, Conlon PJ, Lynn KL, et al. Linkage of a gene causing familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis to chromosome 11 and further evidence of genetic heterogeneity. Genomics. 1999;58:113–120. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ. Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:363–371. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandt DT, Marion S, Griffiths G, Watanabe T, et al. Dial1 and IQGAP1 interact in cell migration and phagocytic cup formation. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:193–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.