Abstract

There are estimated to be approximately 1500 people in the United Kingdom with C1 inhibitor (C1INH) deficiency. At BartsHealth National Health Service (NHS) Trust we manage 133 patients with this condition and we believe that this represents one of the largest cohorts in the United Kingdom. C1INH deficiency may be hereditary or acquired. It is characterized by unpredictable episodic swellings, which may affect any part of the body, but are potentially fatal if they involve the larynx and cause significant morbidity if they involve the viscera. The last few years have seen a revolution in the treatment options that are available for C1 inhibitor deficiency. However, this occurs at a time when there are increased spending restraints in the NHS and the commissioning structure is being overhauled. Integrated care pathways (ICP) are a tool for disseminating best practice, for facilitating clinical audit, enabling multi-disciplinary working and for reducing health-care costs. Here we present an ICP for managing C1 inhibitor deficiency.

Keywords: angioedema, C1 inhibitor, commissioning, icatibant, integrated care pathway

Introduction

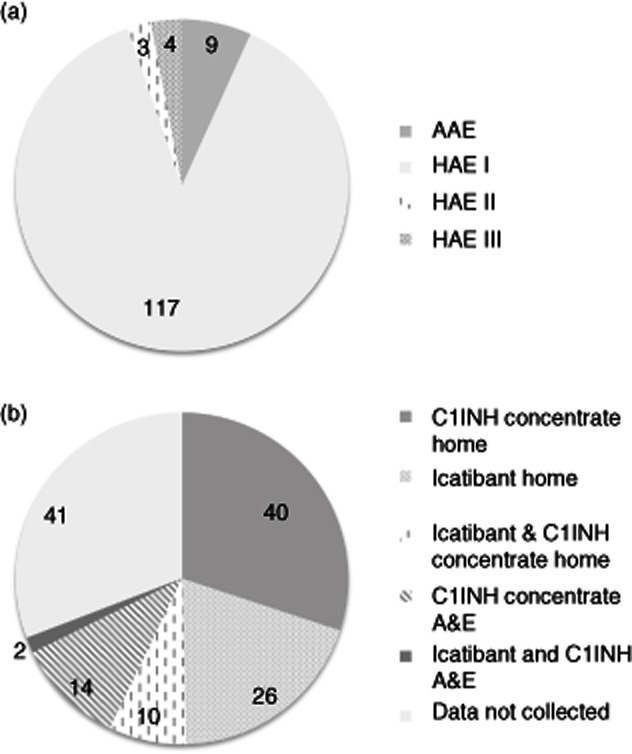

C1 inhibitor (C1INH) deficiency may be inherited [hereditary angioedema (HAE)] or acquired [acquired angioedema (AAE) with C1INH deficiency]. With an estimated prevalence of 1:50 000 for HAE and 1:500 000 for AAE with C1INH deficiency, these conditions are rare and, as a result, most non-specialist physicians are unfamiliar with them 1–3. Hence, in the United Kingdom, long-term management is usually conducted in a tertiary centre by a clinical immunologist, dermatologist or allergist. In some cases, because patients may be required to travel long distances to tertiary centres, care may be shared with more local specialists who have an interest in the condition, such as gastroenterologists or general physicians. At BartsHealth NHS trust we oversee the regular management of 124 patients with HAE and nine patients with AAE with C1INH deficiency – we believe this to be the largest cohort in the United Kingdom, which may be skewed to include some of the most severely affected patients (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

BartsHealth National Health Service (NHS) Trust cohort of patients with C1INH deficiency under regular review (includes 11 paediatric patients). (a) Diagnosis. (b) Acute treatment plan (prescribed medication and setting for emergency treatment – C1INH concentrate includes Berinert, Cinryze and Ruconest). Patients who have both icatibant and C1INH concentrate are advised to take one or the other treatment, depending on the nature and circumstances of their attack.

HAE and AAE with C1INH deficiency are chronic conditions characterized by an unpredictable tendency to develop swellings within the deeper layers of the skin or the mucus membranes 3,4. These swellings may cause airway obstruction if they occur in the upper airway and severe, intractable pain associated with significant fluid shifts and hypotension if they occur in the abdominal viscera. Hence, an acute episode of angioedema can require the patient to attend emergency medical services, and in some cases a hospital, or even intensive care unit (ITU) admission, is necessary. Laryngeal attacks, although relatively infrequent, are associated with a lifetime mortality of up to 40% 5. More than 50% of HAE patients will have a laryngeal attack at some point in their lives, and all are at risk, irrespective of their baseline disease activity. Perhaps more disabling, albeit less visible to the health-care system, are the untreated attacks which interrupt education, cause under- and unemployment, and disrupt family life. In recent years new treatment options have become available for C1INH deficiency, which are based on an improved understanding of the pathophysiology of the condition and robust evidence of efficacy from licensing studies and clinical trials 6–9.

Pathophysiology of C1INH deficiency

The C1INH protein is a serine-protease inhibitor that binds irreversibly to inactivate the proteases factor XIIa and kallikrein, negatively regulating the contact system 10. Therefore, partial deficiency of C1INH, such as occurs in HAE and AAE with C1INH deficiency, shifts the equilibrium of the contact system towards activation and hence results in the accumulation of the active metabolite, bradykinin. Bradykinin is produced from high molecular weight kininogen in a process that is catalyzed by kallikrein. It engages with specific bradykinin receptors in the vascular endothelium to cause vasoldilation, endothelial leakage and consequently the swelling that defines the disease 11,12. C1INH also regulates the complement and fibrinolysis pathways, and it has been proposed that coagulation and fibrinolysis are also involved in the pathophysiology of HAE 13. Moreover, C1INH deficiency is associated with pleiotrophic effects that may impact further upon morbidity, including an enhanced production of autoantibodies, thought to result from increased activation of B cells, which may provide the biological explanation for the reported association of the condition with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) 14,15.

In the case of HAE, the protein insufficiency is usually caused by autosomal dominantly inherited mutations within the C1INH gene that cause a quantitive (type 1 HAE) or functional (type 2 HAE) deficiency, and the onset of the disease occurs typically in childhood 6,16. However, the lack of a family history does not preclude a diagnosis, as an estimated 25% of cases arise from de-novo mutations and the penetrance of the disease is not 100%. Type III HAE is a term to describe patients who show an autosomal dominantly inherited form of angioedema that is not caused by C1INH deficiency, therefore this condition is also referred to as HAE with normal C1INH. A subset of these patients has been found to have mutations in the factor XII gene 17,18. In the case of AAE with C1INH deficiency, the onset of the disease is in adulthood and C1INH deficiency is caused by increased catabolism of the protein and/or inhibitory autoantibodies, usually in association with another disease process such as a lymphoproliferative disorder or connective tissue disease. However, the onset of the angioedema in AAE with C1INH deficiency may precede other clinical evidence of the underlying disease 3,19.

Living with C1INH deficiency

Without prophylaxis, patients average one to two attacks of angioedema per month. Untreated, these last for 48–96 h, but there is considerable variability between patients with regard to the frequency and severity of the attacks 6,20,21. Between episodes of angioedema patients are generally well. Although attacks can be triggered by surgery, trauma, menstruation, pregnancy, infection, stress, anxiety and certain medications (for example, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors), in many cases the precipitant cannot be identified 8,22. Abdominal attacks are reported to be the most distressing aspect of the disease 23. Moreover, the fear of laryngeal attacks which, although infrequent, may occur at any age, adds to the burden of illness. While they may appear less serious, swellings of the hands or feet may prevent patients from being able to do their jobs and in one study even patients on prophylactic treatment with danazol were having an average of 7·7 attacks per year, with their most recent attack causing them to miss an average of 3·3 days of work 24. These issues are compounded by the fact that HAE is an inherited disorder, and so multiple family members may be affected. Studies that have aimed to evaluate the sociological impact of the disease have found that patients with HAE have significantly higher levels of depression, significantly poorer quality of life and decreased work productivity 22.

Treatment of C1INH deficiency

Treatment of C1INH deficiency is based on the management of an established swelling (‘acute treatment’), prevention and attenuation of baseline attacks (‘long-term prophylaxis’) and prevention of attacks at times of increased risk (for example, prior to surgery – ‘short-term prophylaxis’). Advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology of angioedema have driven the development of new treatments for the condition, including a bradykinin receptor antagonist and a kallikrein inhibitor, and advances in molecular genetic technologies have facilitated the development of recombinant C1INH from the milk of transgenic rabbits 7,8. Currently, treatments approved in the United Kingdom for the treatment of acute attacks of HAE include plasma-derived nano-filtered C1INH (Berinert, Cetor and Cirryze), recombinant C1INH (Ruconest/Rhucin) and the bradykinin receptor antagonist (Firazyr/Icatibant). Attenuated androgens and tranexamic acid are used for long-term prophylaxis, but in the United Kingdom these drugs are prescribed off-licence. Cinryze is licensed for both long- and short-term prophylaxis. The kallikrein inhibitor (Ecallantide) does not yet have a licence in the United Kingdom [see section 6 in the evidence base (Supporting information)].

The unfamiliarity of non-specialist medical staff with C1INH deficiency, coupled with the existence of well-organized, motivated patient groups and the rapid development of new therapies, has driven the establishment of a raft of consensus documents for the treatment and management of C1INH deficiency. UK consensus documents, first published in 2005 are currently undergoing revision, and the international consensus documents, first published in 2003, are currently on their third draft 25–27. Consensus documents have been published for the gynaecological and obstetric management of female patients with HAE, home therapy in C1 inhibitor deficiency and for children 28–31. Whereas previously such documents were based primarily on expert opinion, increasingly there is robust evidence generated from licensing studies and clinical trials to support them; the international consensus documents have been supplemented recently to include evidence-based recommendations, and the World Allergy Organization (WAO) has just published an evidence-based guideline 9,32,33. This process is likely to continue as the results of ongoing clinical trials are published. However, in a recent study that surveyed international members of the WAO with responsibility for the management of patients with HAE, more than one-third of physicians described themselves as ‘unfamiliar’ with emerging HAE therapies 34. Furthermore, it was reported that many international physicians neither follow current evidence-based studies nor adhere to the 2010 International Consensus Algorithm for treating HAE 34.

Are patients in the United Kingdom being treated according to consensus?

There is evidence that when treatment for HAE is given early the relief from attacks is faster and the attack less severe, potentially enabling a more rapid return to work and other role activities 20,35–37. Patients report that when they attend emergency facilities for acute treatment medical staff may be unfamiliar with their condition, and they report anecdotally long periods of delay before appropriate treatment is given, even when they present documentation detailing their condition and its treatment. This finding supports the observation that in a survey of 35 Accident and Emergency (A&E) departments across the United Kingdom, only 17 had protocol guidance regarding the use of C1INH, despite the majority having access to the drug 38. In addition, patients report increased confidence in managing their condition when they have access to a home therapy 39. As a result of these factors, many patients and their physicians advocate home therapy whereby patients are taught to treat themselves at home early during an attack, and this approach is supported in both the current UK national and international consensus documents 26,27,29. It is currently very difficult to determine what proportion of patients with C1INH deficiency living in the United Kingdom have access to home therapy, but patient support organizations report that some patients have difficulty obtaining these treatments. The results of a freedom of information request on behalf of the patient group HAE-UK made in 2012 are shown in Table 1. This request also revealed that, of 32 individual funding requests made to Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) for icatibant funding, five were refused 39. These findings suggest that the care patients receive depends upon where they happen to live. Within our cohort, the majority of our patients choose to manage acute exacerbations at home (see Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Response made to freedom of information request made by Hereditory Angioedema (HAE)-UK to 40 Primary Care Trusts (PCT) Clusters in response to the questions: (a) ‘Does your PCT Cluster have a commissioning policy for overall management of HAE’. (b) ‘Does your PCT Cluster have an overall commissioning policy for C1 esterase inhibitor’. (c) ‘Does your PCT Cluster have an overall commissioning policy for icatibant’. (d) ‘Does your PCT Cluster have an overall policy for home use of C1 esterase inhibitor’. (e) ‘Does your PCT Cluster have an overall policy for home use of C1 esterase inhibitor’. Data provided by Ann Price, HAE-UK 57

| Commissioning policy | No | Yes | Mixed | Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Overall management of HAE | 34 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| (b) C1INH concentrate | 31 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| (c) Icatibant | 31 | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| (d) Home use C1INH concentrate | 35 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| (e) Home use icatibant | 34 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

Integrated care pathway for C1IH deficiency

The number of people in the United Kingdom with C1INH deficiency is not known precisely, but based on an estimated prevalence of 1:50 000 for HAE and 1:500 000 for AAE with C1INH deficiency there are likely to be approximately 1500, including a substantial minority undiagnosed or not under specialist care. HAE is included within the Specialized Services National Definition Set, and from April 2013 it will be commissioned nationally 40. Ultimately, this will result in a single commissioning policy for HAE across the country, and hence should end the ‘postcode lottery’ and mean that all patients receive the same standard of care. However, at the same time the NHS is expected to make increasing cost savings, and it is incumbent upon us as physicians to demonstrate, wherever possible, that the best treatment is cost-effective 41. Because the medical management of patients with C1INH deficiency is likely to be shared across several care providers, including the specialist HAE centre (tertiary care), emergency care providers (secondary care) and the general practitioner (primary care), and may be delivered by a range of different health-care professionals, calculating the cost of treatment is complex. Nevertheless, the cost of not treating adequately, in terms of days of productive work missed by the patient, potentially avoidable presentations to emergency services or loss of educational or career opportunity, is not currently well captured and hence the humanistic and economic burden of HAE in Europe is likely to be underestimated 42.

Integrated care pathways (ICP) are a mechanism for mapping how an individual patient interacts with health professionals within primary, secondary and tertiary care over time. The ICP constitutes a document that forms part of the clinical record, capturing all the care given, and hence provides a mechanism for quantitating the associated treatment costs. As they are constructed ideally based on the best available evidence of good practice, they also function as a tool to facilitate the introduction of best practice into routine practice and to enable systematic audit to demonstrate that the standards are being met 43. ICPs are designed to focus on the needs of individuals and families, ensuring that the care they receive is cohesive and offered in a setting most appropriate to the patient, and they were referenced in the recent Departmental of Health review ‘Innovations, Health and Wealth’ as having a role in improving patient and population health 44.

In our trust we oversee the management of 133 patients with C1INH deficiency (see Fig. 1). We are recognized by patient groups and by colleagues as a centre of excellence for the management of HAE. Our integrated care pathway sets out our process for providing cost-effective, evidence-based care within the context and constraints of the UK National Health Service. We hope that by making our local auditable care standard widely available we will stimulate debate and ultimately inform a new UK consensus standard.

Construction of an integrated care pathway for C1INH deficiency

Method

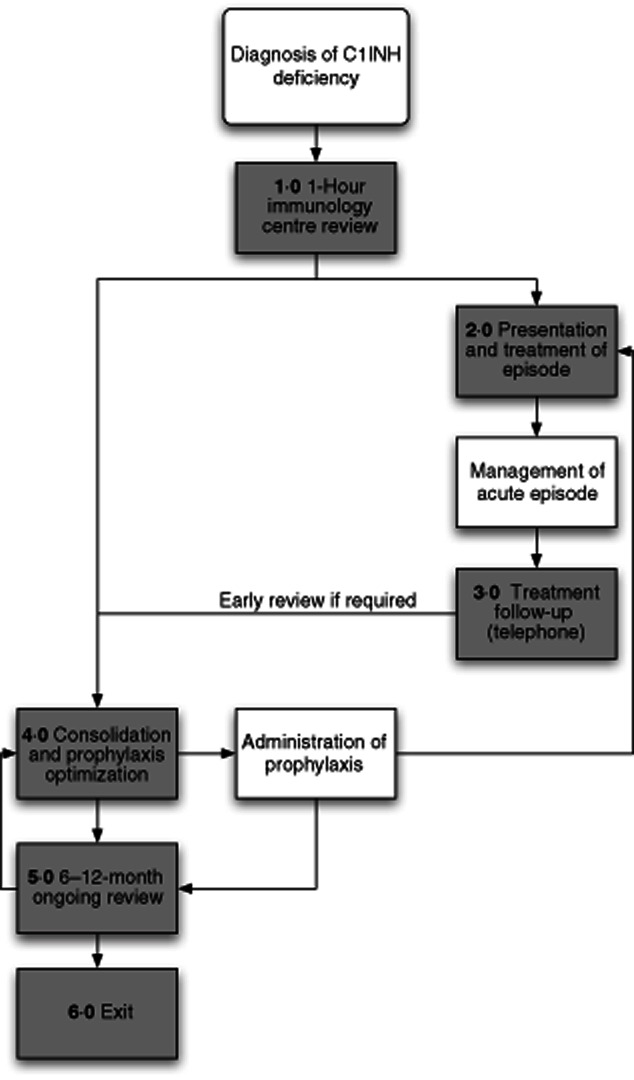

Late in 2011 a multi-agency steering group consisting of clinicians, representatives of patients organizations, specialist nurses, representatives of trust finance, commissioners and pharmacists held a series of meetings to define the pathway delineating our understanding of the patient journey (see Fig. 2). In order to evaluate the evidence base for the interventions defined by each stage of the pathway, a PubMed literature review was conducted using the terms [(HAE or synonym) and (consensus or guideline)]. Key practice points were identified within the consensus documents and used to define treatment goals for each stage of the pathway. Primary clinical trial data were identified from references within the consensus documents and by a further literature search using the search strategy [(HAE or synonym) limited to human trials].

Figure 2.

C1 inhibitor deficiency process map.

The evidence cited in support of the treatment goals was reviewed independently by four appraisers (H.J.L., M.B., S.G. and A.L.M.) and graded according to the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network grading system 45. Where there were discrepancies between grades awarded, these were debated, and if consensus was not reached the majority opinion was recorded. AAE with C1INH deficiency, type II and type III HAE are much less common than type I HAE, and so most of the available evidence pertains to type I HAE. However, mechanistically, it would be predicted that type II HAE, AAE with C1INH deficiency and perhaps type III HAE would respond to treatment similarly, and there is evidence from smaller studies to support this 17,39,46–51. Therefore, these conditions are included in the ICP.

Treatment goals for each stage of the pathway were organized into a data collection form that serves as a template to check that each is achieved in the relevant encounter. These are available for download in the Supporting information.

Structure of the ICP for C1INH deficiency

Entry into the pathway is when C1INH deficiency is diagnosed and the patient is referred to a tertiary centre with specialist knowledge of the condition (see Fig. 2). Each stage of the patient journey is associated with a data collection form (steps 1–6, see Supporting information) which all contain a free text-box labelled ‘patient story’ that enables any issues that the patient wishes to raise that are not recorded on the standard proforma to be documented.

The primary aims of the first appointment, which at our centre is conducted over 1 h, is to confirm the diagnosis of HAE/C1 inhibitor deficiency and to establish the nature of the attacks and their social impact on the patient, in order to establish an individual treatment plan and to provide patient education. The treatment goals for this consultation are captured in the data collection form step 1 (see Supporting information, step 1).

The step 2 data collection form (see Supporting information, step 2) is designed to capture each acute attack and its treatment. It focuses on the evaluation of symptoms, time of onset, the setting for treatment, the treatment(s) given and time to resolution. If the episode results in an emergency care presentation, the form could be completed by the attending health professionals or the patient. If the attack is managed at home, the patient would complete the form themselves.

Step 3 (see Supporting information, step 3) is used to capture a telephone review, usually by the specialist nurse or a physician, that is initiated by the patient if they have a significant attack requiring treatment, have an increased frequency of attacks, are experiencing problems with their treatment or anticipate a need for a change in their treatment (for example, if they require elective surgery). The aim is to establish whether current management is optimal, whether there are any precipitating factors and whether the patient requires early review at the specialist centre (step 4, see Supporting information).

The early review (step 4) is triggered by a serious, inadequately managed or cluster of attacks following telephone review (step 3) or automatically within the first 2 months of the first meeting at the tertiary centre (see Supporting information, step 4). The aim of this meeting is to review the patients understanding of their treatment, to decide whether any further training or information is required and whether any changes to the prophylactic or emergency treatment plan are necessary.

The routine review (see Supporting information, step 5) is a standard follow-up appointment at the specialist centre that at our trust is scheduled on a 6–12-monthly basis. The aim of this review is to ensure that the patient has good control of their disease, a robust mechanism is in place for emergency treatment and that they are not experiencing unacceptable side effects of medication. In addition, the investigations required to monitor treatment side effects are requested and arrangements will be made for the patient to undergo refresher training if they are on home therapy. If disease control is felt to be inadequate then changes to the prophylactic or emergency treatment may be made and an early follow-up appointment (step 4) recommended.

Exit from the pathway (step 6) occurs if, for example, the diagnosis of C1INH deficiency is excluded or the patient transfers to another centre (see Supporting information, step 6).

Discussion

Integrated care pathways (ICP) are a tool for disseminating best practice, for facilitating clinical audit, enabling multi-disciplinary working and for reducing costs 43. They have been identified by the NHS Future Forum and the Department of Health as a mechanism to drive improvement in the new NHS landscape 52. Here we have presented our vision for an ICP for C1INH deficiency based on the available consensus documents, evidence from clinical trials and our experience of managing one of the largest cohorts of patients with this condition in the United Kingdom. We intend to use the data collection forms to audit our own practice, and to begin to capture the social and treatment costs involved for the patients in our cohort, in order to drive improvement. Other immune-mediated diseases could also be approached in this way in order to facilitate best practice across the range of diverse conditions that may be seen in the immunology clinic 53–56. We view this document as a starting-point, and expect the ICP to continue to evolve as it is used more widely and in accordance with new evidence, new drugs being licensed, new guidelines and the feedback we receive.

Acknowledgments

We thank Huw Wilson-Jones (Tower Hamlets Associate Director for Procurement Contracting and Performance), Sarah Santos (Finance Lead at Royal London), Tim Warren (Triducive) and Simon Gwynn (Triducive) for their input into this process and the patients who contributed their stories. The independent steering group was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from CSL Behring, who had no presence in the meetings.

Disclosure

H.J.L. consults to CSL Behring, Pharming, Dyax, Shire and ViroPharma and has acted as a speaker for CSL Behring, Viropharma and Shire. She has received educational and research support from CSL Behring, ViroPharma and Shire and educational support from Pharming. J.D. acts as a consultant to, and has received educational support from, CSL Behring, Shire and ViroPharma. M.S.B. and S.G. have had educational support from Shire and A.L.M. and S.G. from CSL Behring.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Evidence base

ICP step 1

ICP step 2

ICP step 3

ICP step 4

ICP step 5

ICP step 6

ICP steps 1–6

References

- 1.Bygum A. Hereditary angio-oedema in Denmark: a nationwide survey. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1153–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roche O, Blanch A, Caballero T, Sastre N, Callejo D, Lopez-Trascasa M. Hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency: patient registry and approach to the prevalence in Spain. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94:498–503. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agostoni A, Cicardi M. Hereditary and acquired C1-inhibitor deficiency: biological and clinical characteristics in 235 patients. Medicine. 1992;71:206–215. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199207000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bork K, Hardt J, Schicketanz KH, Ressel N. Clinical studies of sudden upper airway obstruction in patients with hereditary angioedema due to C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1229–1235. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.10.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bork K, Siedlecki K, Bosch S, Schopf RE, Kreuz W. Asphyxiation by laryngeal edema in patients with hereditary angioedema. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:349–354. doi: 10.4065/75.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuraw BL. Clinical practice. Hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1027–1036. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0803977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuraw BL. HAE therapies: past present and future. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2010;6:23. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Longhurst H, Cicardi M. Hereditary angio-oedema. Lancet. 2012;379:474–481. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60935-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cicardi M, Bork K, Caballero T, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the therapeutic management of angioedema owing to hereditary C1 inhibitor deficiency: consensus report of an International Working Group. Allergy. 2012;67:147–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pappalardo E, Zingale LC, Terlizzi A, Zanichelli A, Folcioni A, Cicardi M. Mechanisms of C1-inhibitor deficiency. Immunobiology. 2002;205:542–551. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan AP, Joseph K. The bradykinin-forming cascade and its role in hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;104:193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nussberger J, Cugno M, Amstutz C, Cicardi M, Pellacani A, Agostoni A. Plasma bradykinin in angio-oedema. Lancet. 1998;351:1693–1697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09137-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Geffen M, Cugno M, Lap P, Loof A, Cicardi M, van Heerde W. Alterations of coagulation and fibrinolysis in patients with angioedema due to C1-inhibitor deficiency. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167:472–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessel A, Peri R, Perricone R, et al. The autoreactivity of B cells in hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167:422–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan S, Tarzi MD, Dore PC, Sewell WA, Longhurst HJ. Secondary systemic lupus erythematosus: an analysis of 4 cases of uncontrolled hereditary angioedema. Clin Immunol. 2007;123:14–17. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zuraw BL, Herschbach J. Detection of C1 inhibitor mutations in patients with hereditary angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:541–546. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.104780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bork K, Wulff K, Hardt J, Witzke G, Staubach P. Hereditary angioedema caused by missense mutations in the factor XII gene: clinical features, trigger factors, and therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bork K, Wulff K, Meinke P, Wagner N, Hardt J, Witzke G. A novel mutation in the coagulation factor 12 gene in subjects with hereditary angioedema and normal C1-inhibitor. Clin Immunol. 2011;141:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castelli R, Deliliers DL, Zingale LC, Pogliani EM, Cicardi M. Lymphoproliferative disease and acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency. Haematologica. 2007;92:716–718. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bork K, Staubach P, Eckardt AJ, Hardt J. Symptoms, course, and complications of abdominal attacks in hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:619–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bork K, Meng G, Staubach P, Hardt J. Hereditary angioedema: new findings concerning symptoms, affected organs, and course. Am J Med. 2006;119:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lumry WR, Castaldo AJ, Vernon MK, Blaustein MB, Wilson DA, Horn PT. The humanistic burden of hereditary angioedema: impact on health-related quality of life, productivity, and depression. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31:407–414. doi: 10.2500/aap.2010.31.3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bork K, Meng G, Staubach P, Hardt J. Treatment with C1 inhibitor concentrate in abdominal pain attacks of patients with hereditary angioedema. Transfusion. 2005;45:1774–1784. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fust G, Farkas H, Csuka D, Varga L, Bork K. Long-term efficacy of danazol treatment in hereditary angioedema. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41:256–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowen T, Cicardi M, Farkas H, et al. Canadian 2003 international consensus algorithm for the diagnosis, therapy, and management of hereditary angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:629–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gompels MM, Lock RJ, Abinun M, et al. C1 inhibitor deficiency: consensus document. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;139:379–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowen T, Cicardi M, Farkas H, et al. 2010 International consensus algorithm for the diagnosis, therapy and management of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2010;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caballero T, Farkas H, Bouillet L, et al. International consensus and practical guidelines on the gynecologic and obstetric management of female patients with hereditary angioedema caused by C1 inhibitor deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Longhurst HJ, Farkas H, Craig T, et al. HAE international home therapy consensus document. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2010;6:22. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wahn V, Aberer W, Eberl W, et al. Hereditary angioedema (HAE) in children and adolescents – a consensus on therapeutic strategies. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171:1339–1348. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1726-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyle RJ, Nikpour M, Tang ML. Hereditary angio-oedema in children: a management guideline. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16:288–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowen T. Hereditary angioedema: beyond international consensus – circa December 2010 – the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Dr. David McCourtie Lecture. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2011;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craig T, Pursun EA, Bork K, et al. WAO guideline for the management of hereditary angioedema. World Allergy Org J. 2012;5:182–199. doi: 10.1097/WOX.0b013e318279affa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dispenza MC, Craig TJ. Discrepancies between guidelines and international practice in treatment of hereditary angioedema. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012;33:241–248. doi: 10.2500/aap.2012.33.3566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreuz W, Martinez-Saguer I, Aygoren-Pursun E, Rusicke E, Heller C, Klingebiel T. C1-inhibitor concentrate for individual replacement therapy in patients with severe hereditary angioedema refractory to danazol prophylaxis. Transfusion. 2009;49:1987–1995. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tourangeau LM, Castaldo AJ, Davis DK, Koziol J, Christiansen SC, Zuraw BL. Safety and efficacy of physician-supervised self-managed C1 inhibitor replacement therapy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;157:417–424. doi: 10.1159/000329635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maurer M, Aberer W, Bouillet L, et al. Hereditary angiodema attacks resolve faster and are shorter after early icatibant treatment. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e53773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaiganesh T, Hughan C, Webster A, Bethune C. Hereditary angioedema: a survey of UK emergency departments and recommendations for management. Eur J Emerg Med. 2012;19:271–274. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e32834c9e1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boccon-Gibod I, Bouillet L. Safety and efficacy of icatibant self-administration for acute hereditary angioedema. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;168:303–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04574.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Specialised Services National Definitions Set (SSNDS) SSNDS definition no. 16. Specialised clinical immunology services (all ages) (3rd edn) 2010. Available at: http://www.specialisedservices.nhs.uk/info/specialised-services-national-definitions (accessed 5 November 2012)

- 41.Chancellor of the Exchequer. 2010. Spending review 2010 HM Treasury, CM 7942. London, UK: The Stationery Office Ltd.

- 42.Bygum A, Aygoren-Pursun E, Caballero T, et al. The hereditary angioedema burden of illness study in Europe (HAE-BOIS-Europe): background and methodology. BMC Dermatol. 2012;12:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-12-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campbell H, Hotchkiss R, Bradshaw N, Porteous M. Integrated care pathways. BMJ. 1998;316:133–137. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7125.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Department of Health. Innovation health and wealth: accelerating adoption and diffusion in the NHS. 2011. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk (accessed 3 January 2012)

- 45.Harbour R, Miller J. A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. BMJ. 2001;323:334–336. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7308.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levi M, Choi G, Picavet C, Hack CE. Self-administration of C1-inhibitor concentrate in patients with hereditary or acquired angioedema caused by C1-inhibitor deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:904–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bright P, Dempster J, Longhurst H. Successful treatment of acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency with icatibant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:553–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weller K, Magerl M, Maurer M. Successful treatment of an acute attack of acquired angioedema with the bradykinin-B2-receptor antagonist icatibant. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:119–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zanichelli A, Badini M, Nataloni I, Montano N, Cicardi M. Treatment of acquired angioedema with icatibant: a case report. Intern Emerg Med. 2011;6:279–280. doi: 10.1007/s11739-010-0431-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vitrat-Hincky V, Gompel A, Dumestre-Perard C, et al. Type III hereditary angio-oedema: clinical and biological features in a French cohort. Allergy. 2010;65:1331–1336. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bouillet L, Boccon-Gibod I, Ponard D, et al. Bradykinin receptor 2 antagonist (icatibant) for hereditary angioedema type III attacks. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103:448. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60369-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Department of Health. The operating framework for the NHS in England 2012/13 Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk.

- 53.Lachmann H. Clinical Immunology Review Series: an approach to the patient with a periodic fever syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;165:301–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keogan MT. Clinical Immunology Review Series: an approach to the patient with recurrent orogenital ulceration, including Behçet's syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;156:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03857.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.El-Shanawany T, Williams PE, Jolles S. Clinical Immunology Review Series: an approach to the patient with anaphylaxis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;153:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03694.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mousallem T, Burks AW. Immunology in the Clinic Review Series; focus on allergies: immunotherapy for food allergy. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;167:26–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Price A. Freedom of information request made to 40 PCT clusters by HAE UK. 2012.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.