Abstract

The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that high levels of testosterone during prenatal life, testified by a low second-to-fourth digit ratio (2D:4D), as well as in adulthood affect the aggressive behavior of professional soccer players. Using 18 male professional players from a first level Italian Soccer Team we calculated: i) the 2D:4D ratio of the right hand, ii) the number of yellow and red cards per game, iii) the mean salivary testosterone concentration (Sal/T) and iv) the handling of aggressive impulses as assessed by the Picture Frustration test (PFT). Soccer players with a lower 2D:4D ratio had a higher number of fouls per game. A significant negative correlation was observed between Sal/T and 2D:4D ratio, as well as between 2D:4D ratio and the aggressiveness of players. By contrast, a significant positive correlation of Sal/T and fouls/game score and PFT was detected. No significant correlation was detected between 2D:4D or Sal/T and the playing position of players. Results of this study revealed that in professional soccer players, aggressive behavior, with the consequent increased risk of fouls during the game, is more likely to occur in individuals with high testosterone levels, not only in adulthood, but also during their intrauterine life.

Keywords: 2D:4D ratio, aggression, testosterone, soccer, playing positions

Introduction

At the 2006 FIFA World Cup in Germany, millions of people followed live the head-butt given by the French superstar Zinédine Zidane to the Italian defender Marco Materazzi.

Whether this aggressive behavior is the result of innate factors or acquired elements is a matter for debate. Animal studies have indicated a link between incidents of aggression and the individual level of circulating testosterone. However, results in relation to primates, particularly humans, are less clear cut and are at best only suggestive of a positive association in certain contexts (1).

It has been observed in male athletes that testosterone levels before a competition exhibit an increase that precedes the start of the competition and reflects the quality of the performance. In fact, testosterone levels measured in athletes with high-level performances are increased compared with those detected in low-level athletes (2).

It must be emphasized, nevertheless, that several studies in humans did not observe any correlation between testosterone and aggression (3–5). The existence of such a correlation could explain the so-called ‘roid rage’, which is the extremely aggressive behavior associated with the intake of large amounts of anabolic steroids (6,7). However, even if there is an effect of testosterone on aggression at extremely high doses, this does not necessarily suggest that testosterone is effective at physiological concentrations.

It has been suggested that prenatal androgens affect the developing brain by increasing its sensitivity to circulating testosterone later in life (8,9). These effects may include increased self-confidence (10), search persistence (11) and risk preferences (12–14), as well as intensified vigilance and quickened reaction times (15). A number of markers have been proposed for evaluating the effects of prenatal androgens (16), but the most suitable is likely to be the second-to-fourth digit length ratio (2D:4D), with a relatively longer fourth finger (i.e., lower 2D:4D ratio) indicating higher fetal androgen levels (17). However, a previous study (18) concluded that, due to the considerable within-group variability and between-group overlap, digit ratio is not a good marker of individual differences in prenatal androgen exposure. Recently, Manning (19) suggested that 2D:4D is determined not by prenatal androgens alone but by the balance of prenatal androgen to prenatal estrogen signaling in a narrow time window of fetal digit development. For ease of measurement and reproducibility, 2D:4D is used as a substitute measure for prenatal androgen exposure. Support for this use originates from the fact that digit growth and gonadal development are linked by the common influence of Hox genes (17,20). These findings suggest that sex steroids produced by the developing gonads exert significant modulatory effects on digit growth (21). Lower digit ratios have also been shown to correlate with increased sensitivity of androgen receptors (22) and human male reproductive function is negatively correlated with 2D:4D ratio (23). Moreover, 2D:4D ratios appear to be predictive of success among high-frequency financial traders (24), predicting entrance to and success in Medical Schools of state-run Italian Universities (25) and performance of competitive sports, such as basketball (26), skiing (27) and soccer (28).

Professional soccer players have lower 2D:4D ratios than controls. Soccer players in the 1st team squads have lower 2D:4D ratios than reserves or youth team players. Men who had represented their country had lower ratios than those who had not, and there was a significant (one-tailed) negative association between 2D:4D ratios and the number of international appearances after the effect of country was removed. These data suggest that prenatal and adult testosterone promotes the development and maintenance of traits that are useful in sports and athletics disciplines and in male:male fighting (28).

The present study was performed to test the hypothesis that not only high levels of testosterone in adulthood but also higher prenatal testosterone exposure may affect the aggressive behavior of professional soccer players. Specifically, we predicted that players with a lower 2D:4D ratio, due to their aggressive behavior, commit a high number of fouls during the match, punished by the referee by a caution (yellow card) or sending-off (red card).

To test our predictions, we recruited 18 male professional players from a professional soccer team of the ‘Series A’ Italian Football League. We used the numbers of yellow as well as red cards obtained by players as the primary measure of their aggressive behavior. We also measured the levels of salivary testosterone (Sal/T) in players and their aggression using the Picture Frustration test (PFT) by Rosenzweig (29).

Materials and methods

Participants

We recruited 18 male professional players from a first level Italian Soccer Team (Calcio Catania S.p.A.) which participated in the ‘Serie A’ championship 2010/2011 of the Italian Football League. The players received an introductory note that explained briefly that we were looking at the effects of prenatal testosterone on the shape of their right hand, but no information was provided about our hypothesis. Prior to providing a handprint, all the subjects completed a short questionnaire pertaining to their age, medical history and, in particular, whether they had broken the index or ring finger on their right hand. The participants also signed an informed consent form. Participants had a mean height of 1.78 m (±0.06), a mean body mass of 76.9 kg (±5.56) and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 24.2 (±0.53).

The number of played games, the number of min played in each game, and the number of yellow and red cards (fouls) were obtained for each player. In this way, the number of fouls/game (1 game = 90 min) was calculated.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical School at the University of Catania.

Digit ratio measurement

The method used for measuring digit ratio was described by our group in a previous study (25). Briefly, to determine the 2D:4D ratio, we photocopied the players’ right hands and measured the digit length from the metacarpo-phalangeal crease to the finger tip. It has been observed that this crease appears around the 9th week of gestation and is one of the primary creases of the hand (30).

The 2D:4D ratio was determined from only the right hand, as the right-hand digit ratios exhibit more robust gender differences and appear to be more sensitive to prenatal androgens (31,32).

To measure the 2D:4D ratio we used practical recommendations suggested by Voracek et al(33) and those recently described by Coates and Hebert (34). In soft tissue, care must be taken to distinguish regular from irregular or secondary creases. Irregular creases form later than regular creases, after the 11th week of gestation when the fingers start to bend, disrupting the dermal surface (30,35). The handprints of the players were measured to determine 2D:4D ratio by one of the authors (M.C.) using calipers accurate to 0.2 mm.

Hormone assessment

The method used for testosterone assessment was described by our group in a previous study (25). Briefly, saliva samples (1 ml) were collected at rest in sterile containers and stored at −80°C. Sugar-free gum (Vivident Xylit) was used to increase saliva flow in the participants (36). Since in adult males, the excretion of testosterone in saliva appeared to follow a circadian rhythm (37) and to be a pulsatile secretion (38), four samples were collected, at intervals of 30 min, between 9:00 and 1:00 a.m. Saliva was assayed using diagnostic kits (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories Inc., Webster, TX, USA) and modified radioimmunoassay methods (39). The testosterone assay sensitivity was 0.3 pg/ml, with intra-and inter-assay CVs of <9.2 and <8.3%, respectively. Only the highest value of the four measures obtained from each subject was used for the experiments.

Picture frustration test

The method used for PFT assessment was described by our group in a previous study (25). Briefly, the Italian version of the PFT (29,40) permits an evaluation of the subject’s preferred way of handling aggressive impulses. The subject is asked to react verbally to 24 drawings showing common frustration situations by filling out an empty speech bubble for a character experiencing the frustration. The answers are assigned to 3 directions of aggression: ‘extraggression’, ‘intraggression’ and ‘imaggression’. The types of aggression include attending to the frustrating barrier (obstacle dominance), defending the organization of personality (ego-defense) or finding solutions (need-persistence), and some special indices. Descriptions of each factor are shown in Table I [based on (41)].

Table I.

Constructs of reaction to frustration.a

| Type of aggression | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Direction of aggression | Obstacle-dominance (O-D) | Ego-defence (etho-defense) (E-D) | Need-persistence (N-P) |

| Extragression (E-A) | E1 (Extrapeditive): The presence of the frustrating obstacle is (insistently) pointed out. | E (Extrapunitive): Blame, hostility are turned against some person or thing in the environment. E (a variant of E): subject denies that he is responsible for some offense with which he is charged. |

e (Extrapersistive): A solution to the frustrating situation is expected of someone else. |

| Intraggression (I-A) | I1 (Intropeditive): Obstacle is construed as non-frustrating even beneficial; subject can also emphasize his embarrassment for causing another person’s frustration |

I (Intropunitive): Blame, censure are directed by the subject - upon himself. I (a variant of I): subject admits his guilt but denies any essential fault by referring to unavoidable circumstance. |

i (Intropersistive): Amends are offered by the subject, usually from a sense of guilt, to solve the problem. |

| Imaggression (M-A) | M1 (Impeditive): Obstacle of frustration is minimized almost to the point of denying its existence. |

M (Impunitive): Blame for the frustration is evaded altogether, the situation is regarded as unavoidable; the frustrating individual is absolved. |

m (Impersistive): Hope is expressed that time or normally expected circumstances will bring about a solution of the problem; patience and conformity are characteristic. |

Previously shown in ref (25).

Statistical analysis

Data were reported as the means ± SD. Data were collected and averaged, and then compared using unpaired Student’s t-test or one-way repeated measures ANOVA (Friedman test) followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test. Correlation analysis was carried out by using one-tailed Pearson’s correlation analysis; significance was set at P<0.05. All analyses were performed using Systat Software Package version 11 (Systat Inc., Evanston, IL, USA). Statistical analysis was carried out according to guidelines for reporting statistics in journals published by the American Physiological Society (42).

Results

In the present study, we first correlated the different aspects of aggression assessed by PFT with digit ratio. As shown in Table II, the only significant detected correlation was with extraggression-extrapersistive (P<0.05). The other extraggression scores, extrapeditive and extrapunitive, on the PFT test had no significant correlation with the 2D:4D ratio. Additionally, the intraggression and imaggression scores on the PFT test showed no significant correlation.

Table II.

Correlation between RPF scores and 2D:4D ratio.

| RPF test | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Intraggression | Intropeditive | NS |

| Intropunitive | NS | |

| Intropersistive | NS | |

| Imaggression | Impeditive | NS |

| Impunitive | NS | |

| Impersistive | NS | |

| Extraggression | Extrapeditive | NS |

| Extrapunitive | NS | |

| Extrapersistive | <0.05 |

RPF, Rosenzweig picture frustration test; NS, non-significant. Bold, statistically significant.

Table III shows data obtained for each soccer player, i.e., their playing position (goalkeeper, defender, midfielder or attacker), their 2D:4D ratio and Sal/T (pg/ml), their score in PFT test (extraggression-extrapersistive) and the number of fouls obtained per game.

Table III.

Data obtained for the 18 professional soccer players.

| Players | Role | 2D:4D | Sal/T (pg/ml) | PFT (E-A) e | Fouls/game |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | G | 0.99 | 18 | 0.36 | 0.14 |

| 2 | D | 0.94 | 24 | 0.42 | 0.22 |

| 3 | D | 0.98 | 17 | 0.42 | 0.15 |

| 4 | M | 0.98 | 22 | 0.46 | 0.16 |

| 5 | M | 0.96 | 26 | 0.58 | 0.18 |

| 6 | D | 0.94 | 32 | 0.63 | 0.18 |

| 7 | D | 0.96 | 20 | 0.38 | 0.17 |

| 8 | D | 0.98 | 17 | 0.33 | 0.12 |

| 9 | M | 0.97 | 19 | 0.33 | 0.13 |

| 10 | G | 0.96 | 27 | 0.54 | 0.14 |

| 11 | A | 0.95 | 26 | 0.54 | 0.17 |

| 12 | G | 0.95 | 26 | 0.33 | 0.16 |

| 13 | A | 0.97 | 18 | 0.29 | 0.13 |

| 14 | D | 0.97 | 20 | 0.29 | 0.17 |

| 15 | D | 0.97 | 19 | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| 16 | D | 0.95 | 22 | 0.46 | 0.17 |

| 17 | M | 0.94 | 25 | 0.50 | 0.20 |

| 18 | A | 0.96 | 20 | 0.58 | 0.16 |

| Mean | 0.96 | 22.11 | 0.42 | 0.16 | |

| SD | 0.02 | 4.19 | 0.13 | 0.03 |

2D:4D, second-to-fourth digit ratio of the right hand; Sal/T, mean salivary testosterone concentration; PFT (E-A) e, score in PFT test (extraggression - extrapersistive); fouls/game, number of fouls per game (1 game = 90 min); G, goalkeeper; D, defender; M, midfielder; A, attacker. Bold, ?

Firstly, we analyzed the correlation between 2D:4D ratio and the number of fouls obtained by the player per game (Fig. 1A). As expected, players with a lower 2D:4D ratio had a higher number of fouls per game. In fact, the results showed that the lower a player’s 2D:4D ratio, the higher his fouls/game ratio (P=0.0385). Moreover, we studied possible correlations between the 2D:4D ratio of the players and their salivary testosterone concentration (Sal/T). Mean Sal/T of our players was 22.11 pg/ml (±4.19), indicating a significant negative correlation between the two variables (P=0.0002) (Fig. 1B). When the 2D:4D ratio of our players was plotted against their extrapersistive aggressiveness, one of the extraggression characteristics from the PFT (Fig. 1C), we observed a significant negative correlation between the two variables (P=0.0482). No correlation was observed between 2D:4D ratio and the role of the player in the team.

Figure 1.

(A) Correlation between 2D:4D ratio and the number of fouls obtained by the player/game. (B) Correlation between 2D:4D ratio and mean salivary testosterone concentration (Sal/T) of each player. (C) Correlation between 2D:4D ratio and extrapersistive aggressiveness of each player.

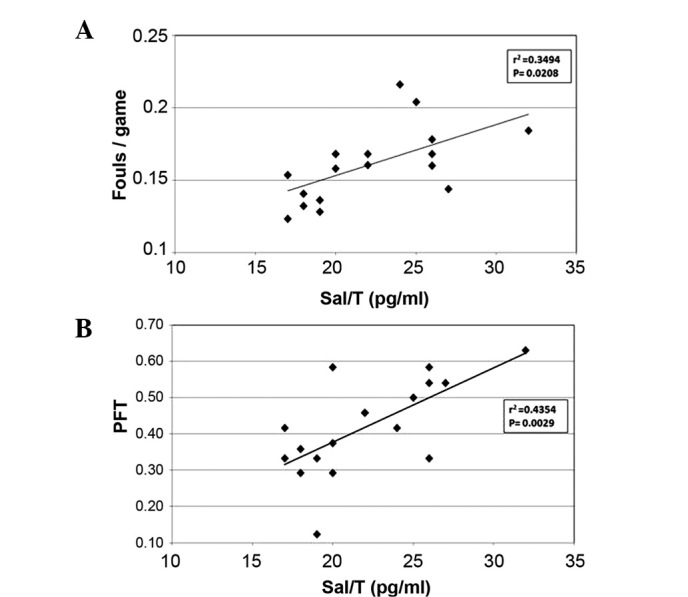

We also attempted to correlate the Sal/T values with fouls/game score and the extrapersistive aggressiveness scores on the PFT test. For the professional players included in this study, a significant positive correlation was observed between Sal/T and fouls/game score (P<0.01) and PFT (P<0.05) (Fig. 2). No significant correlation was detected between Sal/T and the playing position in our sample of soccer players.

Figure 2.

(A) Correlation between mean salivary testosterone concentration (Sal/T) values with fouls/game score of each player. (B) Correlation between Sal/T values with extrapersistive aggressiveness scores on the Picture Frustration test (PFT) of each player.

Discussion

By summarizing our results, we found a significant negative correlation between 2D:4D ratios in our sample of professional soccer players and their salivary testosterone levels, their extrapersistive aggressiveness (i.e., a mindset for which the solution to the frustrating situation is expected of someone else) and their number of fouls per game. No correlation was observed between 2D:4D ratio and the playing positions. Moreover, in the same players we detected a significant correlation between Sal/T and both the number of fouls per game and aggressiveness, but not with playing position.

Our results, beyond confirming the correlation between testosterone levels and 2D:4D ratios, provide support for the hypothesis that 2D:4D ratios predict a higher aggressive behavior and, therefore, a higher risk of fouls during the game.

Many investigators focus on the brain to explain aggression. Electrical stimulation of the hypothalamus causes aggressive behavior (43) and receptors that modulate aggression levels have been identified in the hypothalamus (44). These brain areas have direct connections with both the brainstem nuclei controlling vegetative functions, and with structures such as the amygdala and prefrontal cortex.

Stimulation of the amygdala results in augmented aggressive behavior in hamsters (45,46), while in rhesus monkeys, neonatal lesions in the amygdala or hippocampus result in reduced expression of social dominance, related to the regulation of aggression and fear (47). In many mammals, the circuitry within the amygdala appears to be involved in the control of aggression. However, the role of the amygdala is less clear in primates and appears to depend more on situational context, with lesions leading to increases in either social affiliatory or aggressive responses.

The prefrontal area of the cerebral cortex is involved in aggression, along with many other functions, including inhibition of emotions. Reduced activity of the prefrontal cortex, in particular its medial and orbitofrontal portions, has been associated with violent/antisocial aggression (48).

In a previous study, a significant correlation between 2D:4D ratios and salivary testosterone in adult men was noted (49). However, in the same study, no significant correlation was observed between digit ratio and reactive aggression. The discrepancy may be due to the different methods used for measuring aggression: in the present study we used a validated and widely used test (PFT), whereas Benderlioglu and Nelson (49) utilized an adaptation of the Kulik and Brown (50) method, which is less widespread and not yet validated.

The correlation between baseline testosterone concentrations and aggressiveness, detected in the present study, has been previously observed (25,51–53), although other investigators have failed to replicate this finding (54,55). These contradictory data for aggression may be due, in part, to the use of self-report measures as opposed to the direct measurement of aggressive behavior (56). Additionally, circadian rhythm (37), pulsatile secretion (38) or dynamic fluctuations (57) in testosterone concentrations may be more related to aggressive behavior than mean daily testosterone concentrations. To minimize these possible errors, for the evaluation of aggression, we directly measured aggression of our players by using one of the most commonly used tests (PFT) for this purpose, while testosterone collection was carried out between 9:00 and 12:00 a.m., and 4 samples were collected, at intervals of 30 min. Only the highest value of the four measures obtained from each subject was used for the present experiments.

In conclusion, this study appears to show that, in professional soccer players, aggressive behavior with the consequent increased risk of fouls during the game, is more likely in individuals with high testosterone levels, not only in adulthood, but also during their intrauterine life.

References

- 1.van Bokhoven I, van Goozen SH, van Engeland H, Schaal B, Arseneault L, Séguin JR, Assaad JM, Nagin DS, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE. Salivary testosterone and aggression, delinquency, and social dominance in a population-based longitudinal study of adolescent males. Horm Behav. 2006;50:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazur A, Booth A. Testosterone and dominance in men. Behav Brain Sci. 1998;21:353–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albert DJ, Walsh ML, Jonik RH. Aggression in humans: what is its biological foundation? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1993;17:405–425. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coccaro EF, Beresford B, Minar P, Kaskow J, Geracioti T. CSF testosterone: relationship to aggression, impulsivity, and venturesomeness in adult males with personality disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:488–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Constantino JN, Grosz D, Saenger P, Chandler DW, Nandi R, Earls FJ. Testosterone and aggression in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:1217–1222. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199311000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pibiri F, Nelson M, Carboni G, Pinna G. Neurosteroids regulate mouse aggression induced by anabolic androgenic steroids. Neuroreport. 2006;17:1537–1541. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000234752.03808.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi PY, Cowan D, Parrott AC. High-dose anabolic steroids in strength athletes: effects upon hostility and aggression. Hum Psychopharm Clin. 2004;5:349–356. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breedlove SM, Hampson E. Sexual differentiation of the brain and behaviour. In: Becker J, Breedlove SM, Crews D, McCarthy MM, editors. Behavioral Endocrinology. 2nd edition. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2002. pp. 75–114. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tobet S, Baum M. Role for prenatal estrogen in the development of masculine sexual behavior in the male ferret. Horm Behav. 1987;21:419–429. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(87)90001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boissy A, Bouissou M. Effects of androgen treatment on behavioural and physiological responses of heifers to fear-eliciting situations. Horm Behav. 1994;28:66–83. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrew RJ, Rogers LJ. Testosterone, search behaviour and persistence. Nature. 1972;237:343–346. doi: 10.1038/237343a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Apicella CL, Dreber A, Campbell B, Gray PB, Hoffman M, Little AC. Testosterone and financial risk preferences. Evol Hum Behav. 2008;29:384–390. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Booth A, Johnson D, Granger D. Testosterone and men’s health. J Behav Med. 1999;22:1–19. doi: 10.1023/a:1018705001117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Honk J, Schutter DJ, Hermans EJ, Putman P, Tuiten A, Koppeschaar H. Testosterone shifts the balance between sensitivity for punishment and reward in healthy young women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:937–943. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salminen E, Portin R, Koskinen A, Helenius H, Nurmi M. Associations between serum testosterone fall and cognitive function in prostate cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7575–7582. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen-Bendahan CC, van de Beek C, Berenbaum SA. Prenatal sex hormone effects on child and adult sex-typed behavior: methods and findings. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:353–384. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manning JT, Scutt D, Wilson J, Lewis-Jones DI. The 2nd to 4th digit length: a predictor of sperm numbers and concentrations of testosterone, luteinizing hormone and oestrogen. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:3000–3004. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.11.3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berenbaum SA, Bryk KK, Nowak N, Quigley CA, Moffat S. Fingers as a marker of prenatal androgen exposure. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5119–5124. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manning JT. Resolving the role of prenatal sex steroids in the development of digit ratio. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16143–16144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113312108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paul SN, Kato BS, Cherkas LF, Andrew T, Spector TD. Heritability of the second to fourth digit ratio (2d:4d): a twin study. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9:215–219. doi: 10.1375/183242706776382491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McIntyre M. The use of digit ratios as markers for perinatal androgen action. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2006;4:10–19. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manning JT, Bundred PE, Newton DJ, Flanagan BF. The 2nd to 4th digit ratio and variation in the androgen receptor gene. Evol Hum Behav. 2003;24:399–405. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Auger J, Eustache F. Second to fourth digit ratios, male genital development and reproductive health: a clinical study among fertile men and testis cancer patients. Int J Androl. 2010;34:e49–e58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2010.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coates JM, Gurnell M, Rustichini A. Second-to-fourth digit ratio predicts success among high-frequency financial traders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:623–628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810907106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coco M, Perciavalle V, Maci T, Nicoletti F, Di Corrado D, Perciavalle V. The second-to-fourth digit ratio correlates with the rate of academic performance in medical school students. Mol Med Rep. 2011;4:471–476. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tester N, Campbell A. Sporting achievement: what is the contribution of digit ratio? J Pers. 2007;75:663–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manning JT. The ratio of 2nd to 4th digit length and performance in skiing. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2002;42:446–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manning JT, Taylor RP. Second to fourth digit ratio and male ability in sport: implications for sexual selection in humans. Evol Hum Behav. 2001;22:61–69. doi: 10.1016/s1090-5138(00)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenzweig S. PFS picture-frustration study: manuale integrato delle tre forme per adulti, bambini e adolescenti. Organizzazioni Speciali; Firenze: 1992. p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimura S, Schaumann BA, Plato CC, Kitagawa T. Embryological development and prevalence of digital flexion creases. Anat Rec. 1990;226:249–257. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092260214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manning JT, Churchill AJ, Peters M. The effects of sex, ethnicity, and sexual orientation on self-measured digit ratio (2D:4D) Arch Sex Behav. 2007;36:223–233. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams TJ, Pepitone ME, Christensen SE, Cooke BM, Huberman AD, Breedlove NJ, Breedlove TJ, Jordan CL, Breedlove SM. Finger-length ratios and sexual orientation. Nature. 2000;404:455–456. doi: 10.1038/35006555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voracek M, Bagdonas A, Dressler SG. Digit ratio (2D:4D) in Lithuania once and now: testing for sex differences, relations with eye and hair color, and a possible secular change. Coll Antropol. 2007;31:863–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coates JM, Hebert J. Endogenous steroids and financial risk taking on a London trading floor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6167–6172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704025105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ashbaugh D. Quantitative-Qualitative Friction Ridge Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Ridgeology. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1999. The identification process; p. 234. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dabbs JM., Jr Salivary testosterone measurements: collecting, storing, and mailing saliva samples. Physiol Behav. 1991;49:815–817. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(91)90323-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Landman AD, Sanford LM, Howland BE, Dawes C, Pritchard ET. Testosterone in human saliva. Experientia. 1976;32:940–941. doi: 10.1007/BF02003781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keenan DM, Veldhuis JD. Disruption of the hypothalamic luteinizing hormone pulsing mechanism in aging men. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R1917–R1924. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.6.R1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Granger DA, Schwartz EB, Booth A, Arentz M. Salivary testosterone determination in studies of child health and development. Horm Behav. 1999;35:18–27. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rauchfleisch U. Handbuch zum Rosenzweig Picture-Frustration Test (PFT) Huber; Bern: 1979. p. 399. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tatsuki DH. If my complaints could passions move: an interlanguage study of aggression. J Pragm. 2000;32:1003–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curran-Everett D, Benos DJ. Guidelines for reporting statistics in journals published by the American Physiological Society. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;97:457–459. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00346.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kruk MR, Van der Poel AM, Meelis W, Hermans J, Mostert PG, Mos J, Lohman AH. Discriminant analysis of the localization of aggression-inducing electrode placements in the hypothalamus of male rats. Brain Res. 1983;260:61–79. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90764-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferris CF, Melloni RH, Jr, Koppel G, Perry KW, Fuller RW, Delville Y. Vasopressin/serotonin interactions in the anterior hypothalamus control aggressive behavior in golden hamsters. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4331–4340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04331.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Potegal M, Hebert M, DeCoster M, Meyerhoff JL. Brief, high-frequency stimulation of the corticomedial amygdala induces a delayed and prolonged increase of aggressiveness in male Syrian golden hamsters. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:401–412. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Potegal M, Ferris CF, Hebert M, Meyerhoff J, Skaredoff L. Attack priming in female Syrian golden hamsters is associated with a c-fos-coupled process within the corticomedial amygdala. Neuroscience. 1996;75:869–880. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bauman MD, Toscano JE, Mason WA, Lavenex P, Amaral DG. The expression of social dominance following neonatal lesions of the amygdala or hippocampus in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Behav Neurosci. 2006;120:749–760. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.4.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paus T. Mapping brain development and aggression. Can Child Adolesc Psychiatr Rev. 2005;14:10–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benderlioglu Z, Nelson RJ. Digit length ratios predict reactive aggression in women, but not in men. Horm Behav. 2004;46:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kulik JA, Brown R. Frustration, attribution of blame, and aggression. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1979;15:183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dabbs JM, Carr TS, Frady RL, Riad JK. Testosterone, crime, and misbehavior among 692 male prison inmates. Pers Indiv Differ. 1995;18:627–633. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Archer J. Testosterone and human aggression: an evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:319–345. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sellers JG, Mehl MR, Josephs RA. Hormones and personality: testosterone as a marker of individual differences. J Res Pers. 2007;41:126–138. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Josephs RA, Sellers JG, Newman ML, Mehta PH. The mismatch effect: when testosterone and status are at odds. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;90:999–1013. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.6.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stanton SJ, Schultheiss OC. Basal and dynamic relationship between implicit power motivation and estradiol in women. Horm Behav. 2007;52:571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klinesmith J, Kasser T, McAndrew FT. Guns, testosterone and aggression: an experimental test of a mediational hypothesis. Psychol Sci. 2006;17:568–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hermans EJ, Ramsey NF, van Honk J. Exogenous testosterone enhances responsiveness to social threat in the neural circuitry of social aggression in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]