Abstract

Motivation: RUbioSeq has been developed to facilitate the primary and secondary analysis of re-sequencing projects by providing an integrated software suite of parallelized pipelines to detect exome variants (single-nucleotide variants and copy number variations) and to perform bisulfite-seq analyses automatically. RUbioSeq’s variant analysis results have been already validated and published.

Availability: http://rubioseq.sourceforge.net/.

Contact: mrubioc@cnio.es

1 INTRODUCTION

Primary and secondary data analyses of next-generation sequencing studies (NGS) consist of a set of successive stages that are repetitively and routinely executed using a wide collection of tools (e.g. quality control tools, read aligners, variant callers and so forth). These tools have different origins and usually lack of straight interoperability. This issue has driven computational biologists to demand intuitive, efficient and integrated pipelines to facilitate routine NGS analysis and improve the reproducibility of the results. Several remarkable efforts have been carried out in this sense. Prominent examples include NARWHAL, a recent proposal to automate Illumina’s primary analysis (Brouwer et al., 2012) and HugeSeq, a powerful pipeline designed to cover primary and secondary analysis of single-nucleotide variant (SNVs) and copy number variation (CNV) experiments (Lam et al., 2012). HugeSeq uses FASTQ files as input to detect and annotate genomic variants running GATK (DePristo et al., 2011) and SAMtools; however, the current version of HugeSeq does not support either sample quality control tools or bisulfite-seq (BS-Seq) analysis methods. Galaxy, a large and flexible web-based platform also provides an NGS toolbox (Blakenberg et al., 2010). Despite its potential, Galaxy’s NGS tools are still in β and do not support either CNV or BS-Seq analysis. We present RUbioSeq, an automated and parallelized software suite for primary and secondary analysis of Illumina and SOLiD experiments. Using standard input and output file formats and an intuitive XML configuration file, the application offers an integrated framework to run parallelized pipelines for variant detection in exome enrichment and methylation studies. RUbioSeq results have been experimentally validated and accepted for publication (Domenech et al., 2012).

2 FEATURES AND METHODS

RUbioSeq is highly configurable. The parameters of the analysis are specified in an intuitive XML configuration file, which allows customization of the pipeline. Every RUbioSeq workflow accepts single- and paired-end experiments and detects Illumina’s CASAVA version automatically. We have included additional quality control steps to check the integrity of the inputs and the BAM files generated. RUbioSeq workflows are divided into functional modules that may be executed independently. The results are saved in a project directory tree maintaining a structured organization for the output files. Further details are available in the user manual at http://rubioseq.sourceforge.net/.

2.1 SNVs detection pipeline

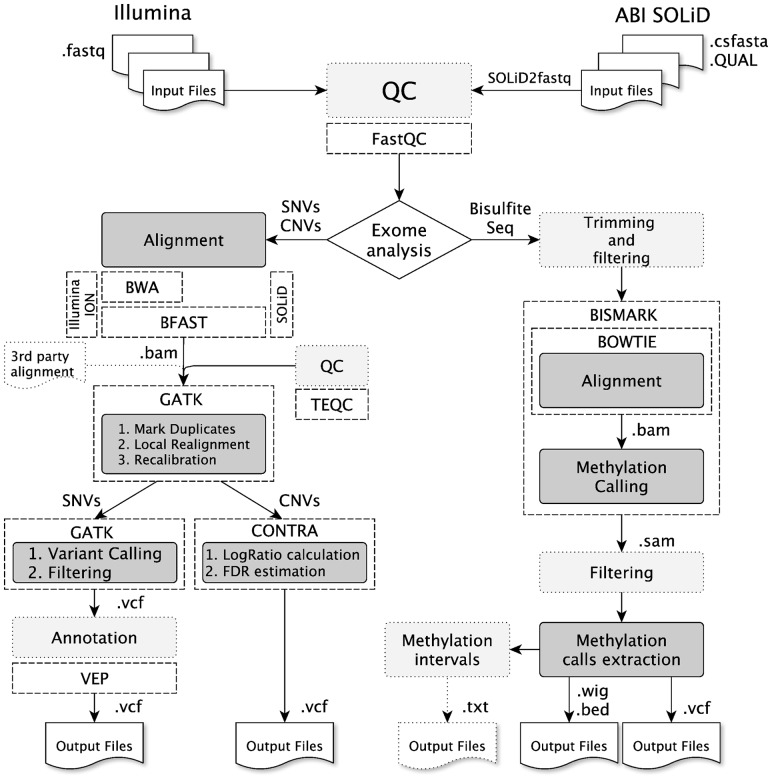

The primary input files accepted by RUbioSeq are reads in FASTQ (Illumina) or CSFASTA/QUAL (SOLiD) format. Alternatively, BAM alignment files are supported as input (Fig. 1). SNV pipeline is divided into three main modules: (i) short-read alignment with a combination of BWA + BFAST aligners (Li and Durbin, 2009; Homer et al., 2009) and quality control analysis using FastQC, (ii) duplicate marking using Picard tools, realignment and recalibration using GATK, and TEQC as quality control and (iii) GATK variant calling, tumor/control somatic indels detection and advanced filtering using GATK’s VariantFiltration walker. Finally, variants are annotated using Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (VEP, McLaren et al., 2010). All the output files are generated in standard formats, such as BAM and VCF (Danecek et al., 2011; Li et al., 2009).

Fig. 1.

RUbioSeq pipelines for exome variant detection and BS-Seq analyses. Dark gray boxes correspond to the main steps of the pipelines. Light gray boxes indicate optional steps

2.2 CNV detection pipeline

RUbioSeq’s CNV detection pipeline uses the modules (i) and (ii) described in Section 2.1 to generate GATK recalibrated BAM files. Then CONTRA software uses recalibrated BAMs to perform the CNV analyses for case–control comparisons (Li et al., 2012). CONTRA calls copy number gains and losses based on normalized depth of coverage, generating output files in standard VCF format (Fig. 1).

2.3 Bisulfite-seq pipeline

RUbioSeq requires bisulfite-converted reads in FASTQ format as input. The software accepts input data generated from Cokus et al. (2008) and Lister et al. (2009) protocols (Krueger et al., 2012). This pipeline has been structured in three analysis modules: (i) read filtering, FastQC quality control, bisulfite sequence alignment and methylation calling using Bismark, (ii) depth filtering and output files generation and (iii) an optional interval methylation percentages calculation (Fig. 1). The lack of standard output format for methylation-calls has encouraged us to adapt this output to the widely established VCF format. See RUbioSeq’s documentation for further details.

2.4 Implementation details

RUbioSeq is written in Perl. Its modular design provides a high flexibility to facilitate the inclusion of additional functionalities in future versions of the tool. RUbioSeq has been implemented to run on UNIX HPC systems scheduled by SGE or PBS. The software allows pipelines to be launched in a UNIX workstation as well. We have also implemented a parallelized and multithreaded execution of the analysis process enabling different levels of execution. RUbioSeq’s workflows are prepared to perform multiple samples simultaneously on an HPC system. Under this parallelized design, the real execution time for N samples (N * t) is reduced to t, where t represents execution time for one sample. This feature can be executed in two ways: Standalone multisample where every sample generates an independent result and Joint multisample where all samples contribute to a unique final result.

2.4.1 Analysis protocols

All the implemented code and programs used in RUbioSeq are open-source. Our modules use state-of-art software, such as BWA and BFAST aligners, GATK variant caller and Ensembl’s VEP. We have set RUbioSeq’s parameters with defaults established in best practice recommendations provided by developers for each of the analysis tasks and platforms supported. We have also set-up platform-specific alignment protocols. For instance, for Illumina exome variation analysis, the software takes advantage of BWA efficiency and BFAST sensitivity by first performing a BWA alignment step and then a BFAST alignment for those reads unmapped at the first step. Next, RUbioSeq generates the output BAM file containing all the mapped reads that will be accepted by RUbioSeq’s downstream execution module.

2.4.2 Benchmarking

RUbioSeq has been executed in a 24 node Intel Nehalem cluster with 16 cores (2.67 Ghz each core) and 48 GB of ransom access memory per node. The variant detection workflow generated full lists of genomic variants in 3 h for an Illumina paired-end experiment carried out in 10 chronic lymphocytic leukemia samples (CLLs) and their corresponding healthy controls (SRA ID: SRA049097). This study covered coding and regulatory regions belonging to 301 genes (1.36 Mb) associated to CLLs (Domenech et al., 2012). We additionally tested our software with BS-Seq data available from the NIH Roadmap Epigenomics consortium. We used the Illumina’s H1 cell line sample (SRS004212) from the UCSD Human Reference Epigenome Mapping Project (SRP000941). We have analyzed 10 FASTQ files (∼1.5 GB per file) using the joint multi-sample execution mode and the default parameters. The final results (without bowtie-build) were generated in ∼3.5 h.

3 CONCLUSIONS

We have developed RUbioSeq, an integrated and parallelized workflow for DNA-Seq and BS-Seq studies. As RUbioSeq depends on >20 different software packages, we have created a customized 64-bit LiveDVD (based on Ubuntu 12.10 Desktop LiveCD), which bundles RUbioSeq plus all its dependencies, ready to be used on any computer. The results generated by RUbioSeq have been validated and accepted for publication. RUbioSeq source code and full documentation are accessible under Creative Commons License at http://rubioseq.sourceforge.net.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank CNIO Lymphoma group, UBio staff, F. Al-Shahrour and E. Carrillo for experimental validation, technical assistance and fruitful discussions.

Funding: M.R-C. is funded by BLUEPRINT Consortium (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement number 282510. J.M.F is funded by the Spanish National Institute of Bioinformatics (INB) a project by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (BIO2007-666855).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Blakenberg D, et al. Galaxy: a web-based genome analysis tool for experimentalists. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1910s89. Chapter 19, Unit 19.10.1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer RW, et al. NARWHAL, a primary analysis pipeline for NGS data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:284–285. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokus SJ, et al. Shotgun bisulphite sequencing of the Arabidopsis genome reveals DNA methylation patterning. Nature. 2008;452:215–219. doi: 10.1038/nature06745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P, et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2156–2158. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePristo M, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenech E, et al. New mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia identified by target enrichment and deep sequencing. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homer N, et al. BFAST: an alignment tool for large scale genome resequencing. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger F, et al. DNA methylome analysis using short bisulfite sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:145–151. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam HY, et al. Detecting and annotating genetic variations using the HugeSeq pipeline. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:226–229. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, et al. The sequence alignment/map (SAM) format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, et al. CONTRA: copy number analysis for targeted resequencing. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1307–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462:315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren W, et al. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP Effect predictor. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2069–2070. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]