Abstract

Motivation: RNA-seq techniques provide an unparalleled means for exploring a transcriptome with deep coverage and base pair level resolution. Various analysis tools have been developed to align and assemble RNA-seq data, such as the widely used TopHat/Cufflinks pipeline. A common observation is that a sizable fraction of the fragments/reads align to multiple locations of the genome. These multiple alignments pose substantial challenges to existing RNA-seq analysis tools. Inappropriate treatment may result in reporting spurious expressed genes (false positives) and missing the real expressed genes (false negatives). Such errors impact the subsequent analysis, such as differential expression analysis. In our study, we observe that ∼3.5% of transcripts reported by TopHat/Cufflinks pipeline correspond to annotated nonfunctional pseudogenes. Moreover, ∼10.0% of reported transcripts are not annotated in the Ensembl database. These genes could be either novel expressed genes or false discoveries.

Results: We examine the underlying genomic features that lead to multiple alignments and investigate how they generate systematic errors in RNA-seq analysis. We develop a general tool, GeneScissors, which exploits machine learning techniques guided by biological knowledge to detect and correct spurious transcriptome inference by existing RNA-seq analysis methods. In our simulated study, GeneScissors can predict spurious transcriptome calls owing to misalignment with an accuracy close to 90%. It provides substantial improvement over the widely used TopHat/Cufflinks or MapSplice/Cufflinks pipelines in both precision and F-measurement. On real data, GeneScissors reports 53.6% less pseudogenes and 0.97% more expressed and annotated transcripts, when compared with the TopHat/Cufflinks pipeline. In addition, among the 10.0% unannotated transcripts reported by TopHat/Cufflinks, GeneScissors finds that >16.3% of them are false positives.

Availability: The software can be downloaded at http://csbio.unc.edu/genescissors/

Contact: weiwang@cs.ucla.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

RNA-seq techniques provide an efficient means for measuring transcriptome data with high resolution and deep coverage (Ozsolak and Milos, 2011). Millions of short reads sequenced from cDNA provide unique insights into a transcriptome at the nucleotide-level and mitigate many of the limitations of microarray data. Although there are still many remaining unsolved problems, new discoveries based on RNA-seq analysis ranging from genomic imprinting (Gregg et al., 2010) to differential expression (Anders and Huber, 2010; Trapnell et al., 2012) promise an exciting future.

Current RNA-seq analysis pipelines typically contain two major components: an aligner and an assembler. An RNA-seq aligner [e.g. TopHat (Trapnell et al., 2009), SpliceMap (Au et al., 2010) and MapSplice (Wang et al., 2010)] attempts to determine where in the genome a given sequence comes from. An assembler [e.g. Cufflinks (Trapnell et al., 2010) and Scripture (Guttman et al., 2010)] addresses the problems of which transcripts are present and estimating their abundances.

Existing RNA-seq pipelines can be divided into two major categories: align-first pipelines and assembly-first pipelines (Ozsolak and Milos, 2011). Assembly-first pipelines attempt to assemble and quantify the complete transcriptome without a reference. Several algorithms, such as Trinity (Grabherr et al., 2011) and TransABySS (Robertson et al., 2010), have been developed. However, alignment to a reference genome is still necessary to interpret the results from an assembly-first pipeline and to relate them to existing knowledge. The assembly-first pipeline is compute-intensive and may require several days to complete. In align-first pipelines, a high-quality reference genome serves as a scaffold for inferring the source of RNA-seq fragments. Current alignment approaches are both computationally efficient and easily parallelized. Thus, the align-first RNA-seq analysis can be finished within hours even on a normal desktop machine. Therefore, align-first pipelines such as TopHat/Cufflinks (Trapnell et al., 2010, 2012) or MapSplice/Cufflinks (Wang et al., 2010) are generally preferred when a suitable reference genome is available.

1.1 Multiple-alignment problem

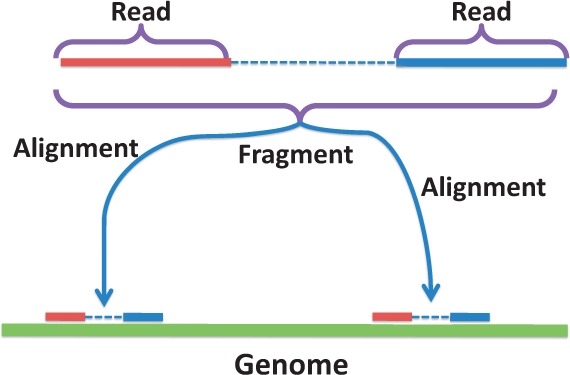

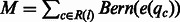

In this article, we assume that the RNA-seq data are paired-end reads, which are widely used for transcriptome inference. Our approach can be used for single-end reads as well. In paired-end RNA-seq data, a fragment is a sub-sequence from an expressed transcript. High-throughput sequencing provides two reads corresponding to the two ends of the fragment. If a fragment can be mapped to more than one location in the genome, we say that this fragment has multiple alignments, as showed in Figure 1. As each fragment originates from one location in the genome, multiple alignments must be processed/corrected before subsequent analysis can proceed. Inappropriate handling of the multiple alignment fragments impacts the subsequent analysis and may lead to questionable conclusions. For example, the ‘widespread RNA and DNA sequence differences’ (Li et al., 2011) are suspected to be (at least partially) due to systematic technical errors, including misalignments (Kleinman and Majewski, 2012).

Fig. 1.

A fragment with paired end reads that can be aligned to two locations in the genome

Current RNA-seq analysis pipelines handle the multiple-alignment problem in both the alignment and assembly steps. Most existing aligners [e.g. TopHat (Trapnell et al., 2009)] use a scoring system where only the alignments with the ‘best score’ are kept. However, a fragment may still have multiple alignments with equally good scores. In our experiments on real mouse RNA-seq data, we observe that at least 5% fragments have multiple alignments. The assembler [e.g. Cufflinks (Trapnell et al., 2010)] either assumes that they contribute equally to each location or uses a probabilistic model to estimate their contributions based on the abundance of the corresponding transcripts (Li et al., 2010).

1.2 Genomic factors causing multiple alignments

In general, multiple alignments are caused by the existence of paralogous sequences within a genome. Duplicated and repetitive sequences need not be strictly identical. In this subsection, we discuss genomic factors that may lead to multiple alignments and their impact on RNA-seq analysis. Retrotransposition and gene duplication are two biological phenomena that generate sequences with high levels of nucleotide similarity. Interspersed highly repetitive sequences, such LINEs and SINEs, can be expressed in an autonomous or nonautonomous manner, but they are not our focus. That leaves us with three major types of genomic factors: processed pseudogenes (Balakirev and Ayala, 2003; Vanin, 1985; Zhang et al., 2003), nonprocessed pseudogenes (Hurles, 2004) and repetitive sequences shared by gene families (Häsler et al., 2007; Jurka and Smith, 1988).

Pseudogenes (Harrison et al., 2003; Khelifi et al., 2005) are typically nonfunctional, though some of them may be expressed (Hirotsune et al., 2003). They can be further categorized in two groups: processed pseudogenes and nonprocessed pseudogenes based on their causes. Both of them lead to the repetitive genomic sequences. In general, the pseudogenes are nonfunctional and under reduced selection pressure; thus, they typically exhibit a higher mutation rate than the expressed genes from which they originated.

1.2.1 Processed pseudogene

A processed pseudogene (Vanin, 1985) is generated when an mRNA is reverse transcribed and reintegrated back to the genome. The resulting DNA sequence of the processed pseudogene is the concatenated exon sequences from its original transcript. Because there are no splice junctions in the sequence of the processed pseudogene, it is easier for the current RNA-seq aligners to map the fragments to processed pseudogene than the actual gene from which they are expressed, especially those fragments that cross a splice junction. Both the unexpressed pseudogene and its corresponding expressed gene may be reported by the assembler if the implementation of the assembler does not consider such cases. For example, Guttman et al. (2010) observed that a few highly expressed transcripts may not be able to be fully reconstructed owing to alignment artifacts caused by the processed pseudogenes.

1.2.2 Nonprocessed pseudogene

Nonprocessed pseudogenes (Hurles, 2004) are typically caused by a historical gene duplication event, followed by an accumulation of mutations, and an eventual loss of function. Nonprocessed pseudogenes often share similar exon/intron structures with their originating gene. From the aligner’s perspective, fragments can be mapped to either the expressed original gene, or its nonprocessed pseudogene, or both. Similar to processed pseudogenes, the assembler may report a nonprocessed pseudogene when its corresponding functional genes are expressed.

1.2.3 Repetitive shared sequences

Besides pseudogenes, many functional gene families share subsequences that are almost identical to each other. One repetitive sequence shared by different genes in human genome is Alu (Häsler et al., 2007; Jurka and Smith, 1988). Consider the case when, among all genes that share the Alu sequence, but only a subset is expressed. Hence, the aligner will map the fragments originating from the expressed subset to all similar sequences on the genome. The assembler may report all genes sharing the repetitive sequence as being expressed.

Any of these three biological factors may lead to multiple alignments. Without proper post-processing, an assembler may report many unexpressed pseudogenes or even random regions as expressed genes, and it may also miss a few highly expressed genes.

Existing RNA-seq analysis pipelines provide heuristics for addressing the multiple alignment problem, however, they do not explicitly consider their genomic causes. In our study, using mouse RNA-seq data, the transcripts reported by Cufflinks include ∼3.5% from known pseudogenes and ∼10% from unannotated regions. A quarter of these 13.5% transcripts are likely to be false positives caused by multiple alignments.

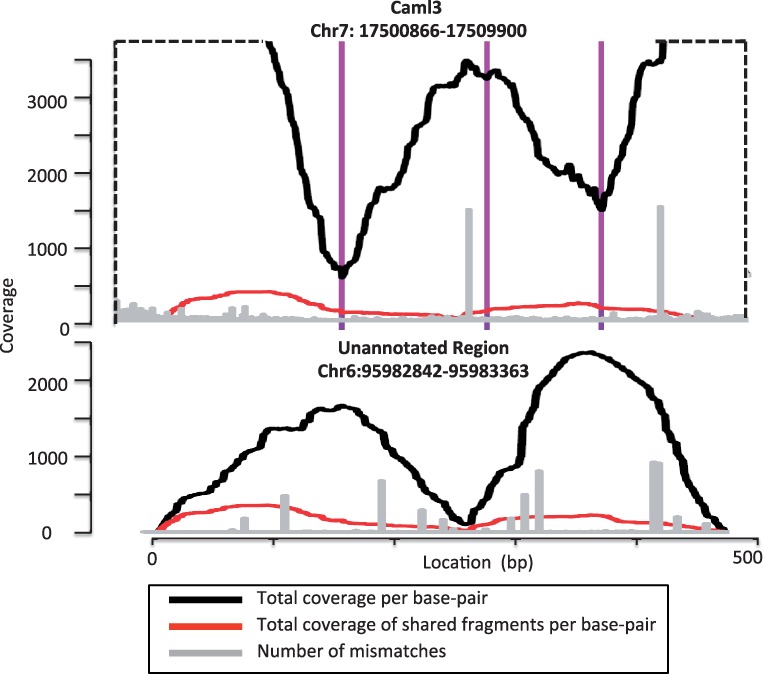

Figure 2 shows the pile-up plots of two regions from a mouse genome reported by a current RNA-seq pipeline. The top one is a gene named Caml3, whereas the bottom one is unknown. The unknown gene’s sequence is similar to the sequence of concatenated exons from Caml3. Fragments that are uniquely aligned to the unknown gene by the aligner can also be aligned to Caml3. However, the aligner fails to find the proper alignment because it does not consider all possible alignments crossing splice junctions owing to the search complexity. This collection of evidence indicates that the unknown gene is actually an unannotated processed pseudogene of Caml3.

Fig. 2.

Two transcripts reported by Cufflinks. The top one maps to a known gene named Caml3, and the bottom one does not map to any known gene. Two transcripts are aligned by their shared fragments in the plot. Owing to the space limitation, the top figure is truncated, and only shows the region containing shared fragments. The dashed line indicates the truncated boundary. The three vertical lines in purple represent three splice junctions in the top transcript

Therefore, the identification of expressed genes and unexpressed pseudogenes is a significant confounding factor in RNA-seq analysis. No existing analysis methods explicitly attempt to identify and reassign fragments that are mapped to pseudogenes. A similar observation was made by ContextMap (Bonfert et al., 2012) that multiple alignments from a RNA-seq aligner could be handled by removing the incorrect alignments based on the ‘context’ of the alignments. However, ContextMap simply defines the ‘context’ as a fixed window around the alignment on the genome. It also does not try to rescue any missed alignments. In contrast, we introduce the concept of fragment attractor, which leverages the results from both an aligner and an assembler to determine the appropriate ‘context’ for each individual alignment. Sharing maps between fragment attractors are built to help discover and restore missed alignments.

In this article, we introduce the GeneScissors pipeline, a comprehensive approach to address the problem of detecting and correcting those fragments errantly aligned to unexpressed genomic regions. When compared with the standard TopHat/Cufflinks pipeline, GeneScissors is able to remove 57% pseudogenes without using any annotation database. GeneScissors can reduce inference errors in existing analysis pipelines and aid in distinguishing truly unannotated genes from errors.

2 METHODS

In this section, we present GeneScissors, a general component that can be applied to any align-first RNA-seq pipeline to detect and correct errors in transcriptome inference owing to fragment misalignments. In a standard RNA-seq pipeline, the ‘best’ alignment for a fragment with multiple alignments is determined without considering the surrounding alignments of other fragments. Such decisions may be premature without considering the other fragments aligned to these regions. In the GeneScissors pipeline, we first collect all possible alignments for all fragments, and then examine those regions of the genome where multiple alignments map and then consider the other fragments aligned to these regions. In this way, GeneScissors is able to leverage statistics of fragment distribution and other features of the alignments.

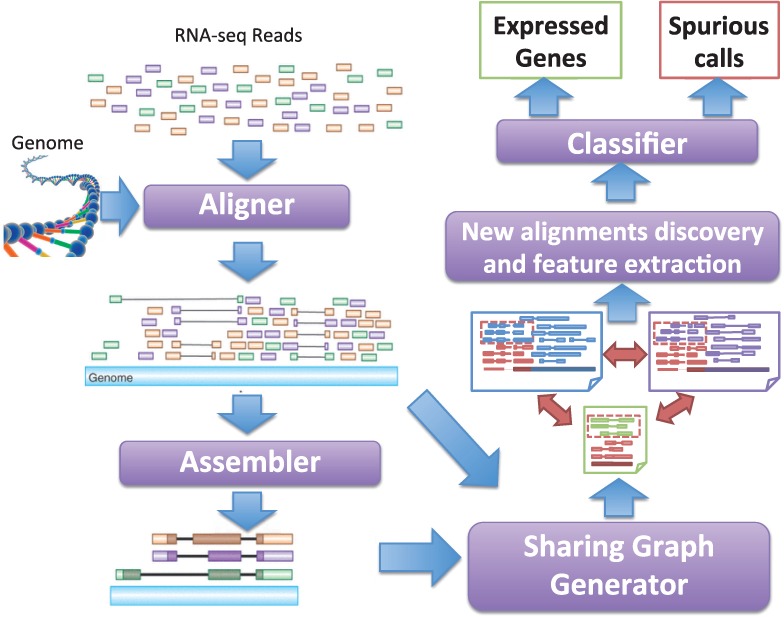

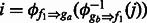

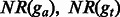

Figure 3 describes the proposed workflow for RNA-seq analysis. It uses existing aligner and assembler (with minor modifications to keep all possible alignments discovered, details in Section 3.1) to identify regions to which fragments align. To distinguish from expressed genes, we refer to each such region as a fragment attractor. Fragments with multiple alignments link corresponding fragment attractors. We refer to these fragments and their alignments as shared fragments and shared alignments, respectively. The relationships among linked fragment attractors are defined by their shared fragments. GeneScissors uses sharing graphs to represent the linked fragment attractors and to discover new fragment alignments. We create training instances using simulated RNA-seq fragments from annotated genes in Ensembl to build a classification model. Then, on real data, the classification model predicts and removes the fragment attractors that are likely due to misalignments. Existing assembly methods can be applied on the remaining fragment alignments to re-estimate the abundance level of expressed fragment attractors. We introduce the sharing graph in Section 2.1, a classification model to identify the unexpressed fragment attractors in Section 2.2 and the features extraction method from the sharing graphs in Section 2.3.

Fig. 3.

The workflow of GeneScissors Pipeline. The traditional RNA-seq analysis pipeline is the path on the left side. Its alignment and assembly results are used by GeneScissors to infer fragment attractors, build sharing graphs and identify all fragment alignments in the genome. GeneScissors then builds a classification model to detect and remove unexpressed genes

2.1 Sharing graph

We construct sharing graphs as follows. Each fragment attractor is represented by a node, and each pair of linked fragment attractors are connected by an edge. Each connected component is called a sharing graph. For each edge in a sharing graph, we build a position-by-position sharing map between the pair of linked fragment attractors through their shared fragments. For any fragment f aligned to a fragment attractor g, we first define function  , which returns the aligned position in fragment attractor g, given a position in fragment f and its inverse function

, which returns the aligned position in fragment attractor g, given a position in fragment f and its inverse function  , which returns the corresponding position in f (if it exists), given a position in g. For a pair of linked fragment attractors ga and gb and one of their shared fragments f1, position k in f1 may be aligned to position i in fragment attractor ga and position j in gb. This provides a correspondence between position i in ga and position j in gb by

, which returns the corresponding position in f (if it exists), given a position in g. For a pair of linked fragment attractors ga and gb and one of their shared fragments f1, position k in f1 may be aligned to position i in fragment attractor ga and position j in gb. This provides a correspondence between position i in ga and position j in gb by  and

and  . A sharing map can be built between ga and gb through this approach by using all their shared fragments. It is possible that two shared fragments f1 and f2 map the same position in ga to two different positions in gb, i.e.

. A sharing map can be built between ga and gb through this approach by using all their shared fragments. It is possible that two shared fragments f1 and f2 map the same position in ga to two different positions in gb, i.e.  . Empirically, such cases are rare, and when it happens, we use the majority rule to resolve the conflict.

. Empirically, such cases are rare, and when it happens, we use the majority rule to resolve the conflict.

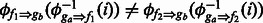

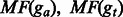

The region of a fragment attractor that is covered by the sharing map is called the shared region. In addition to the shared fragments, some other fragments uniquely aligned to the fragment attractor may align to the shared region. These fragments should have been aligned to the linked fragment attractor too, but the aligner might have failed to recognize the alignments owing to the reasons we discussed previously. Therefore, with the help of the sharing map, we can ‘restore’ these missed alignments from existing aligner’s result. For example, in Figure 4a, we show a sharing graph among three fragment attractors. The red regions in the bottom row of each fragment attractor are the shared regions. The red dashed boxes contain the fragments uniquely aligned to one fragment attractor by the aligner but should have been aligned to the linked fragment attractors too. In Figure 4b, we show more details on how the new alignments of the fragments are established through the sharing map. This alignment discovery operation needs to be done in both directions for each pair of linked fragment attractors. In our previous example in Figure 2, the uniquely aligned fragments (between the black curve and the red curve) in the shared regions should have been aligned to both fragment attractors. Restoring fragment alignments to multiple positions does not cause inflation in abundance level estimation because transcriptome inference methods such as Cufflinks already consider the shared alignments. This approach enables us to safely rescue fragment alignments missed by an aligner.

Fig. 4.

(a) A sharing graph of three fragment attractors A, B and C. Each solid box represents a pile-up of fragments of a fragment attractor. Each pair of connected hollow rectangles represents a fragment of paired end reads. The red fragments are the shared fragments that can be mapped by the aligner to all three fragment attractors. The bottom row in each box represents the transcript sequence. The red regions (except the splice junctions in the transcript sequences) are the region to which the shared fragments align. (b) A sharing map between fragment attractors A and C and the discovered new alignments (shown in dashed rectangles). These new alignments are rescued from the uniquely aligned fragments in the shared region of one of the two fragment attractors

2.2 Classification model

GeneScissors processes RNA-seq data at the granularity of linked fragment attractors. Because there is no easy way to determine whether a fragment attractor are expressed in real datasets, we build our training model from simulated data and apply it to real data. We first generate our training set from a simulated population, and each sample is a set of fragments simulated based on a set of selected transcripts from the annotation database. (More details are in Section 3.1). Then, we apply the aligner and the assembler on each sample of the simulated data, build the sharing graphs based on their results and generate training instances from the sharing graphs. The fragment attractors that cannot be mapped back to the selected transcripts are unexpressed ones. We use a classification model to infer whether a fragment attractor (hereby referred to as the target fragment attractor gt) is expressed using features of gt and another fragment attractor (hereby referred to as the assistant fragment attractor ga) linked to gt by an edge in the sharing graph. For every pair of linked fragment attractors, we build two instances. The instance is labeled according to whether the target fragment attractor is expressed. Therefore, one fragment attractor may be the target fragment attractor in multiple instances. The intuition is that, for an unexpressed target fragment attractor, there should always be some instances in which the assistant fragment attractors are expressed. In such instances, the assistant fragment attractor should have less consistent mismatches, longer sequence and lower proportion of shared fragments than the target fragment attractor (More details are in Section 2.3, which describes all features we use). Thus, we can train a binary classification model using these features to identify unexpressed target fragment attractors. When we apply the model to test data and real data, all target fragment attractors, which are predicted as unexpressed at least once will be removed from the result of the assembler, and the reads that are uniquely aligned to these fragment attractors will be redistributed to the corresponding expressed fragment attractors. We experimented with support vector machines (SVMs), DecisionTrees and RandomForests as the learning method and found that RandomForests had the best overall performance. Once the classifier is built, we apply it on test data to evaluate the prediction accuracy and then apply it to real data to predict unexpressed fragment attractors and remove their fragment alignments. Recall that, for all uniquely aligned fragments in the shared regions of these fragment attractors, we also discover new alignments to their linked fragment attractors using the sharing map.

2.3 Fragment attractor features

We extract features from both target fragment attractor gt and assistant fragment attractor ga in each instance. Each instance contains 14 features, listed in Table 1. All features except the number of consistent mismatch locations are straightforwardly calculated: features NE and NI are directly collected from the assembler’s output, and NR, MF, MR and CM are calculated by our sharing graph generator. The use of consistent mismatch count CM, as a feature is motivated by the observation that the pseudogenes usually have higher mutation rate. The concept of consistent mismatch and the method to find consistent mismatch locations across the genome are described in Appendix 1. The number of exons is helpful in distinguishing processed pseudogenes, which are singletons. All the other features are motivated by our observation that the unexpressed fragment attractors tend to have smaller number of alignment fragment and shorter region than their corresponding expressed ones.

Table 1.

The features used for detecting fragment attractors resulting from misalignments

| Features | Description |

|---|---|

|

and and  are the observed numbers of exons. These two Boolean features tell whether the genes are singleton of exons. are the observed numbers of exons. These two Boolean features tell whether the genes are singleton of exons. |

|

are the proportions of the fragments that can be aligned to ga and gt to the total fragments, respectively. are the proportions of the fragments that can be aligned to ga and gt to the total fragments, respectively. |

|

are the proportions of the shared fragments to the fragments aligned ga and gt, respectively. are the proportions of the shared fragments to the fragments aligned ga and gt, respectively. |

|

are the proportions of the entire regions of ga and gt that are covered by shared fragments. are the proportions of the entire regions of ga and gt that are covered by shared fragments. |

|

are the numbers of base pairs that have consistent mismatches in the shared regions of ga and gt, respectively. are the numbers of base pairs that have consistent mismatches in the shared regions of ga and gt, respectively. |

3 RESULTS

We first describe a series of modifications made to open-source RNA-seq analysis tools to support GeneScissors. Then, we describe the various datasets used for evaluation. We evaluated two standard pipelines that do not use GeneScissors: one using TopHat and the second using MapSplice as an aligner. We then added GeneScissors to each pipeline, to improve the alignment results, and we refer to these as GeneScissors(TopHat) and GeneScissors(MapSplice) pipelines. All four pipelines use Cufflinks as the transcriptome assembler.

3.1 Software

GeneScissors uses modified versions of TopHat and Cufflinks and uses components written in C++, Python and the BamTools (Barnett et al., 2011) library. Cuffcompare is used to map the reported genes back to Ensembl annotations and categorize them into three types: annotated normal genes/transcripts, annotated pseudogenes and unannotated regions.

3.1.1 Modifications to TopHat and Cufflinks

We first present the algorithms used by TopHat and Cufflinks in ranking and reporting alignments and genes and then discuss our modifications to retain all fragment and partial fragment (unpaired reads) alignments.

In TopHat, if the fragment f has multiple alignments x and y, TopHat retains only alignment y and does not report alignment x, when one of the following conditions is satisfied (tests are applied in order):

Mismatch rule: x has more mismatches than y.

Splice junction rule: x crosses more splice junctions than y.

Other rules: Owing to the space limitations, we omit the conditions that are not relevant to the article.

Only alignments with the best score are reported by TopHat. We observed that the splice-junction rule tends to favor processed pseudogenes; the correct alignment of a fragment with a splice junction is frequently discarded by TopHat if the fragment can be aligned to a processed pseudogene with the same number of mismatches.

In Cufflinks, a gene that meets the following criteria is suppressed:

75% rule: More than 75% of the fragment alignments supporting the gene are mappable to multiple genomic loci.

Consider the example shown in Figure 2. Cufflinks fails to remove the unannotated pseudogene, which is composed mostly of uniquely aligned fragments. This suggests that the 75% rule is insufficient.

Therefore, in the GeneScissors pipeline, we disabled the splice junction rule in TopHat and the 75% rule in Cufflinks.

3.1.2 Simulator

To generate training data for our classification model and evaluate the effectiveness of GeneScissors for detecting and removing unexpressed fragment attractors, we built a RNA-seq simulator to provide a ‘ground truth’ model for fragment attractors. The simulator randomly chooses a (user-specified) number of genes, and for each gene, it samples a subset of its transcripts. Then, it uniformly samples paired-end fragments up to a certain abundance level for each selected transcript. For each fragment, it assigns a quality score to each base pair, drawing from an empirical distribution derived from real data, and generates base pair errors based on their quality scores.

3.2 Data

Our study used inbred and F1 crosses of three mouse strains: CAST/EiJ, PWK/PhJ and WSB/EiJ. To minimize the impact of unknown SNPs to the alignments, we generated strain-specific genomes by incorporating high-confidence SNPs detected in a recent DNA sequencing project of laboratory mouse strains conducted by the Welcome Trust (Keane et al., 2011) into the mm9 reference genome. We used the Ensembl database (build 63) (Flicek et al., 2011) to annotate and evaluate the results from real and simulated data.

3.2.1 Simulated Data

A RNA-seq simulator was used to generate synthetic data from 60 RNA-seq samples also derived from three inbred mouse strains: CAST/EiJ, PWK/PhJ and WSB/EiJ. In each sample, we selected  annotated functional genes in Ensembl as the expressed genes and randomly set them to different levels of abundance. Many genes included multiple transcripts. We generated 10 million fragments with 100 base pair paired-end reads for each sample. We used TopHat and MapSplice as aligners and Cufflinks as the assembler to analyze the simulated data. More than 7.5% of the genes reported in the results were not from the selected genes in our simulation setting. From the results, we built shared graphs and used cross-validation to train and test our model. A feature selection study using the simulated data can be found in the supplementary material.

annotated functional genes in Ensembl as the expressed genes and randomly set them to different levels of abundance. Many genes included multiple transcripts. We generated 10 million fragments with 100 base pair paired-end reads for each sample. We used TopHat and MapSplice as aligners and Cufflinks as the assembler to analyze the simulated data. More than 7.5% of the genes reported in the results were not from the selected genes in our simulation setting. From the results, we built shared graphs and used cross-validation to train and test our model. A feature selection study using the simulated data can be found in the supplementary material.

3.2.2 Real data

We applied GeneScissors to RNA-seq data from nine inbred samples and 53 F1 samples derived from three inbred mouse strains CAST/EiJ, PWK/PhJ and WSB/EiJ. We sequenced cDNA from mRNA extracted from brain tissues of three to six replicates of both sexes and the six possible crosses (including the reciprocal). To mitigate misalignment errors owing to heterozygosity, for each F1 sample, we aligned each fragment to the genome of each parent separately (i.e. the mm9 reference sequence with annotated SNPs) and then merged the two alignments while retaining all distinct multiple alignments (a union of the set of all mapped fragments each identified by their mapping coordinate and read identifier). For comparison purposes, we also applied this alignment strategy in the TopHat and MapSplice pipelines.

3.3 Results from simulated data

In Table 2, we first present the average precision, recall, F scores and Area under the Curve when LinearSVM, DecisionTree and RandomForests were used to build the classification models. All scores were measured by 10-fold cross-validation. The results demonstrate that our feature set is adequate and can help detect unexpressed genes efficiently. The RandomForests is the best and most consistent among all three methods. The classification model trained by RandomForests can detect near 90% spurious calls owing to misalignments. Though SVM has a slightly higher precision score, the recall is much lower than RandomForests. This is because RandomForests is more suitable than SVM for data with discrete features and is more powerful in handling correlations between features. Therefore, we chose RandomForests as the default classification method for our GeneScissors pipeline.

Table 2.

Summary of the results from different classification methods

| Statistics | LinearSVM | DecisionTree | RandomForests |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | 81.90% | 83.70% | 89.60% |

| Recall | 83.00% | 84.80% | 87.80% |

| F-measurement | 85.70% | 84.20% | 88.60% |

| Area under the curve | 0.843 | 0.837 | 0.91 |

Next, we investigated how much improvement GeneScissors could bring to the overall transcriptome calling by correcting fragment misalignment. We compared the results of our improved GeneScissors pipelines with those from the TopHat and MapSplice’s pipelines. Both GeneScissors pipelines used the modified version of Cufflinks. The GeneScissors (TopHat) pipeline used the modified version of TopHat. The MapSplice and TopHat pipelines used the regular version of Cufflinks. We used the following three measurements to compare the performance at the gene level:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

The results of different pipelines are summarized in Table 3. All statistics are averaged over a 10-fold cross-validation. We observe that Cufflinks tends to report a much higher number of genes in all four pipelines. There are only ∼13 000 expressed genes, but Cufflinks reports >30 000 genes in the TopHat or MapSplice pipelines and >26 000 genes in the GeneScissors pipelines.

Table 3.

Comparison of MapSplice, TopHat, GeneScissors (MapSplice) and GeneScissors (TopHat) pipelines

| Statistics | MapSplice pipeline | TopHat pipeline | GeneScissors (MapSplice) | GeneScissors (TopHat) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of reported genes | 36 516 | 30 622 | 26 556 | 26 473 |

| GenePrecision | 35.6% | 41.8% | 48.2% | 48.3% |

| GeneRecall | 95.1% | 93.2% | 93.0% | 93.2% |

| GeneF-measurement | 51.5% | 58.2% | 63.5% | 63.6% |

Note: The bold value of each row represents the best pipeline measured by the corresponding metric.

A significant percentage of these reported genes can be mapped back to the ‘expressed’ genes from which we generated synthetic reads. Several reported genes are often mapped back to the same expressed gene by Cuffcompare. Cufflinks failed to recognize them as (possibly different transcripts of) the same gene, perhaps owing to both the length and variable number of splice junctions and/or the low fragment coverage seen for some transcripts. In this case, when we computed GenePrecision and GeneRecall, only one of them was counted as the ‘correct’ gene, the remaining ones were counted as ‘incorrect’ genes. As all four pipelines used Cufflinks to infer transcriptome, all of them had relatively low GenePrecision. The GeneScissors (MapSplice) pipeline had a 12.6% improvement in GenePrecision over the original MapSplice pipeline, at the cost of a slight drop in GeneRecall. The GeneScissors (TopHat) pipeline had a 6.5% improvement in GenePrecision over the TopHat pipeline while retaining the same level of GeneRecall. GeneScissors was able to detect and remove >4000 spurious (gene) calls by correcting fragment misalignments.

We also observed that the MapSplice pipeline has the highest score on GeneRecall, but a much lower GenePrecision score comparing with TopHat pipeline and GeneScissors pipeline. This is because MapSplice can find more possible alignments than TopHat but is not able to identify the correct alignment when a fragment has multiple alignments. Hence, the MapSplice pipeline reported more false positives than the TopHat pipeline.

Overall, the GeneScissors (TopHat) pipeline performed best among the four pipelines on this challenging test case. It is obvious that (i) detecting and correcting fragment misalignments can improve the accuracy in transcriptome inference under all circumstances and (ii) given the correct fragment alignments, better transcriptome inference algorithms are still needed. In addition, GeneScissors does not assume all pseudogenes are unexpressed. GeneScissors is able to distinguish expressed pseudogenes from the rest with a comparable accuracy, demonstrated by a simulation study in the supplementary material.

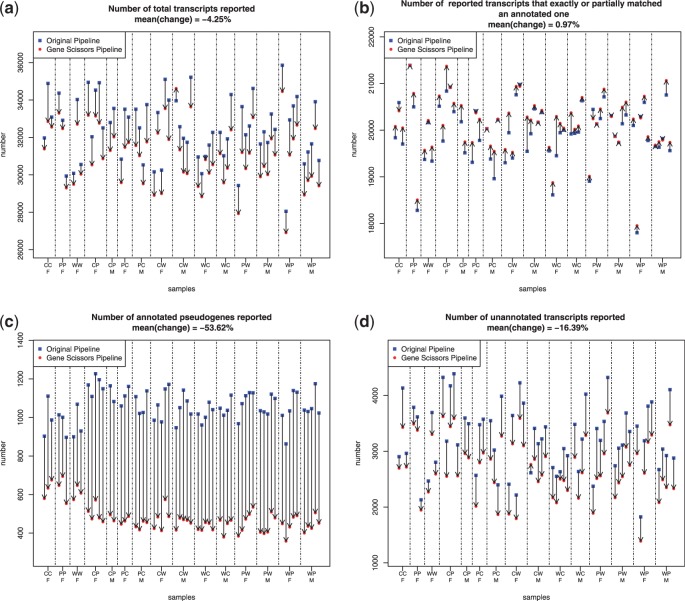

3.4 Results from real RNA-seq data

We also applied both TopHat pipeline and our GeneScissors (TopHat) pipeline on the real RNA-seq data. The running time for TopHat pipeline was ∼24 h per sample, and the extra running time for GeneScissors (TopHat) pipeline were ∼10 h per sample. Overall, the GeneScissors (TopHat) pipeline reported 4.25% fewer transcripts in real data than the TopHat pipeline (Fig. 5a). Considering that GeneScissors removed most of false positives in our simulation study, it suggests that the transcripts reported by the TopHat pipeline include a significant number of false positives.

Fig. 5.

Comparisons between multiple samples run through both the GeneScissors pipeline and the TopHat pipeline. Results from the same sample are connected by an arrow. The three strains used were CAST/EiJ, PWK/PhJ and WSB/EiJ, and they are indicated by the initials C, P and W, respectively. The two letter designations indicate the direction of the cross with the initial of the maternal strain followed by the initial of the paternal strain. The samples are clustered according to replicates from the same sex and F1 cross, followed by the reciprocal cross. The sex is indicated by F(female) and M(male)

Despite the fewer number of transcripts reported by GeneScissors, Figure 5b shows that GeneScissors actually reported 0.97% more transcripts that exactly match or partially match the splice junction annotations in the Ensembl database than the TopHat pipeline (The improvement is statistically significant with a P-value lower than  under the paired student’s t-test). These transcripts are likely the false negatives missed by the TopHat pipeline owing to misalignments. Figure 5c shows that the TopHat pipeline reported >800 transcripts that are annotated as pseudogenes in Ensembl. GeneScissors managed to remove >53.6% of them, and the fraction of transcripts that overlap any pseudogenes decreased from 3.2 to 1.57%. Figure 5d shows that GeneScissors reported 16% fewer unannotated transcripts than the TopHat pipeline. All these results indicate that GeneScissors is effective in detecting and correcting false positive and false negative transcript reports caused by fragment misalignments.

under the paired student’s t-test). These transcripts are likely the false negatives missed by the TopHat pipeline owing to misalignments. Figure 5c shows that the TopHat pipeline reported >800 transcripts that are annotated as pseudogenes in Ensembl. GeneScissors managed to remove >53.6% of them, and the fraction of transcripts that overlap any pseudogenes decreased from 3.2 to 1.57%. Figure 5d shows that GeneScissors reported 16% fewer unannotated transcripts than the TopHat pipeline. All these results indicate that GeneScissors is effective in detecting and correcting false positive and false negative transcript reports caused by fragment misalignments.

Furthermore, the number of pseudogenes reported by the original TopHat/Cufflinks pipeline in inbred samples is fewer than the number in F1 hybrids. Similarly, the fraction of pseudogenes ( ) removed by GeneScissors in the inbred samples is smaller than the fraction (

) removed by GeneScissors in the inbred samples is smaller than the fraction ( ) removed in the F1 hybrids. This indicates that the additional complications of F1 samples pose additional challenges to RNA-seq analysis pipelines and makes them more prone to errors than the inbred samples.

) removed in the F1 hybrids. This indicates that the additional complications of F1 samples pose additional challenges to RNA-seq analysis pipelines and makes them more prone to errors than the inbred samples.

4 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this article, we presented GeneScissors, a general approach to detect and correct transcriptome inference errors caused by misalignments, which can be applied to any RNA-seq analysis pipeline. GeneScissors considers three underlying biological factors that lead to fragment misalignments and spurious transcript reporting. We proposed a classification model to detect false discoveries owing to misalignment, and the results show that it can provide significant improvement in overall accuracy.

Other heuristic approaches have been used to avoid reporting unexpressed genes in the RNA-seq assembly result, such as discarding all known pseudogenes reported by the TopHat pipeline, masking repeated elements in genome or aligning fragments to known transcriptome instead of genome. The key difference is that our RNA-seq analysis does not require any additional annotations beyond adding SNPs, and it still supports a novel ‘transcript discovery’.

Transcript discovery is important because current annotations are incomplete with regard to genes, isoforms and allele-specific variants. For example, in the real data, we observed ∼4000 unannotated transcripts clustered ∼2300 unannotated genes on average. These transcripts persist after applying GeneScissors, which attempts to identify and correct misaligned fragments. This implies that current annotations are neither complete nor entirely accurate. For example, recent studies (Hirotsune et al., 2003; Khelifi et al., 2005) found that some regions previously thought to be pseudogenes can actually be transcribed to mRNA. Hence, removing all annotated pseudogenes or highly repeated regions may lead to the removal of actual expressed transcripts. In contrast, GeneScissors might choose a pseudogene over the annotated paralog based on which better matches known genetic variants.

Furthermore, current pipelines using Cufflinks tend to overreport genes, especially when the genes share a high degree sequence similarity with other expressed genes in the data. The problem is alleviated to some extent by GeneScissors by recovering missed multiple fragment alignments and discarding fragment alignments to unexpressed genes/regions. However, there is still room for improvement.

In the future work, though our precision and recall scores are near 90%, we plan to exploit additional features and constraints to improve the classification accuracy. Example constraints include that each sharing graph must contain at least one expressed gene and each shared fragment must belong to an expressed gene. In addition, we plan to investigate how to rescue the discarded fragment alignments to an unexpressed fragment attractor, but not in the shared regions with any linked fragment attractors because these fragments should belong to some expressed genes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank those center members who prepared and processed samples as well as those who commented on and encouraged the development of GeneScissors; in particular, Weibo Wang, Isa-Kemal Pakatci, Zhishan Guo, John Calloway, James J. Crowley and Patrick F. Sullivan. They also thank three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments.

Funding: [NIMH/NHGRI P50 MH090338], [NIH GM P50 GM076468], [NSF IIS-1313606], [NSF IIS-0812464].

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Appendix 1

CONSISTENT MISMATCHES

For a given base pair location in the genome, if the number of aligned fragments that carry an allele different from the reference genome is much higher than the expected number owing to random sequencing errors, we call it a consistent mismatch location. There are three possible reasons that a consistent mismatch occurs: (i) A missing SNP or heterozygous site in a diploid sample’s genome (inconsistency between the reference DNA sequence and the sample’s DNA sequences), (ii) an RNA-editing site, and (iii) misaligned fragments (difference between the sequences of a gene and its pseudogene). Consider the example shown in Figure 2, there are two visible consistent mismatches on the expressed gene, Caml3, and they are due to either of the first two reasons (an unreported SNP, a heterozygous SNP, or an RNA-editing event). Because the fragments aligned to the unannotated region originated from Caml3, in the pile-up plot of the unannotated region, there are more than six visible consistent mismatches owing to the third reason (misaligned fragments).

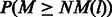

It is important to separate the consistent mismatches from the mismatches owing to sequencing errors. We assume that the sequencing error rate of a given base pair c in a given fragment is reflected in its quality score qc and can be derived as a function  . Given a base pair location l in the genome, let R(l) be the set of base pairs aligned to the location. The number of mismatches NM(l) at this location should follow a sum of Bernoulli distributions with different success probabilities, which is

. Given a base pair location l in the genome, let R(l) be the set of base pairs aligned to the location. The number of mismatches NM(l) at this location should follow a sum of Bernoulli distributions with different success probabilities, which is  . The P-value of the location is defined as

. The P-value of the location is defined as  . A significant P-value indicates that this location may be a consistent mismatch location. To find all consistent mismatch locations, we first need to estimate the sequencing error rate. The original function to calculate the error rate is

. A significant P-value indicates that this location may be a consistent mismatch location. To find all consistent mismatch locations, we first need to estimate the sequencing error rate. The original function to calculate the error rate is

In this calculation, we need to exclude the consistent mismatches that are not caused by sequencing errors. This can be done iteratively, starting from an initial estimation using all positions that have at least ten fragments aligned. In each iteration, we mask positions on the genome that have much higher mismatch rate than the current estimated error rate and re-estimate the error rate. We use the empirical distribution of e as the new estimation of e. For the positions that contain less than three mismatches, we first calculate the following two probabilities in  time complexity:

time complexity:

| (4) |

| (5) |

then we calculate the exact probability as the P-value:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

The number of mismatches at a position should be equal to a sum of Bernoulli distributions with different parameters, and the distribution of the sum can be approximated by a Poisson distribution based on Le Cam’s inequality Le Cam (1960):

Therefore, the P-value can be approximated by

The positions with P-values less than  are classified as consistent mismatch locations. This process continues until no more consistent mismatch locations are found. This threshold is empirically determined because current threshold gives us the best performance to identify the unexpressed genes.

are classified as consistent mismatch locations. This process continues until no more consistent mismatch locations are found. This threshold is empirically determined because current threshold gives us the best performance to identify the unexpressed genes.

REFERENCES

- Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au KF, et al. Detection of splice junctions from paired-end RNA-seq data by SpliceMap. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4570–4578. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakirev ES, Ayala FJ. Pseudogenes: are they “junk” or functional DNA? Ann. Rev. Genet. 2003;37:123–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.040103.103949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett DW, et al. BamTools: a C++ API and toolkit for analyzing and managing BAM files. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1691–1692. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfert T, et al. A context-based approach to identify the most likely mapping for RNA-seq experiments. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13(Suppl. 6):S9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-S6-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicek P, et al. Ensembl 2012. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;40:D84–D90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg C, et al. High-resolution analysis of parent-of-origin allelic expression in the mouse brain. Science. 2010;329:643–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1190830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M, et al. Ab initio reconstruction of cell type–specific transcriptomes in mouse reveals the conserved multi-exonic structure of lincRNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:503–510. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PM, et al. Identification of pseudogenes in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1033–1037. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häsler J, et al. Useful ‘junk’: Alu RNAs in the human transcriptome. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007;64:1793–1800. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7084-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotsune S, et al. An expressed pseudogene regulates the messenger-RNA stability of its homologous coding gene. Nature. 2003;423:91–96. doi: 10.1038/nature01535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurles M. Gene duplication: the genomic trade in spare parts. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J, Smith T. A fundamental division in the Alu family of repeated sequences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:4775–4778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, et al. Mouse genomic variation and its effect on phenotypes and gene regulation. Nature. 2011;477:289–294. doi: 10.1038/nature10413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khelifi A, et al. HOPPSIGEN: a database of human and mouse processed pseudogenes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D59–D66. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman CL, Majewski J. Comment on ‘Widespread RNA and DNA sequence differences in the human transcriptome’. Science. 2012;335:1302–1302. doi: 10.1126/science.1209658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Cam L. An approximation theorem for the poisson binomial distribution. Pacific J. Math. 1960;10:1181–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Li B, et al. RNA-Seq gene expression estimation with read mapping uncertainty. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:493–500. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, et al. Widespread RNA and DNA sequence differences in the human transcriptome. Science. 2011;333:53–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1207018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozsolak F, Milos PM. RNA sequencing: advances, challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:87–98. doi: 10.1038/nrg2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson G, et al. De novo assembly and analysis of RNA-seq data. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:909–912. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, et al. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:516–520. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanin EF. Processed pseudogenes: characteristics and evolution. Ann. Rev. Genet. 1985;19:253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.19.120185.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, et al. MapSplice: accurate mapping of RNA-seq reads for splice junction discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e178. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, et al. Millions of years of evolution preserved: a comprehensive catalog of the processed pseudogenes in the human genome. Genome Res. 2003;13:2541–2558. doi: 10.1101/gr.1429003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.