Abstract

Most of default mode network (DMN) studies in patient with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) were based only on the comparing two groups, namely patients and controls. Information derived from comparing the three groups, normal, aMCI, and AD group, simultaneously may lead us to better understand the progression of dementia. The purpose of this study was to evaluate functional connectivity of DMN in the continuum from normal through aMCI to AD. Differences in functional connectivity were compared between the three groups using independent component analysis. The relationship between the functional connectivity and disease progression was investigated using multiple regression analysis with Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores. The results revealed differences throughout the left posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), left middle temporal gyrus (MTG), right middle frontal gyrus (MFG), and bilateral parahippocampal gyrus (PHG). Both patients with aMCI and AD showed decreased connectivity in the left PCC and left PHG compared with healthy subjects. Furthermore, patient with AD also showed decreased connectivity in the left MTG and right PHG. Increased functional connectivity was observed in the right MFG of patients with AD compared with other groups. MMSE scores exhibited significant positive and negative correlations with functional connectivity in PCC, MTG and MFG regions. Taken together, an increased functional connectivity in the MFG for AD patients might compensate for the loss of function in the PCC, MTG via compensatory mechanisms in cortico-cortical connections.

Keywords: Resting-state, Functional magnetic resonance imaging, Alzheimer’s Disease, Mild Cognitive Impairment, Default Mode Network

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia and is characterized by the formation of neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (Braak & Braak, 1996), whereas mild cognitive impairment (MCI) refers to a transitional state between the cognition of normal aging and dementia (Petersen et al., 1999). Although MCI may evolve into dementia with various etiologies or even return to a normal cognitive state, still many studies have suggested that amnestic subtype of MCI (aMCI), characterized by episodic memory loss, is a robust indicator of an increased likelihood of development of MCI into AD (Gauthier et al., 2006; Yaffe et al., 2006).

Recently, low-frequency fluctuations approach during the resting-state (RS) has been widely used to analyze functional connectivity in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) (Biswal et al., 1995). One major finding of RS fMRI studies was notion of default mode network (DMN), which is internally driven conceptual processing that occurs during the conscious RS (Binder et al., 1999; Greicius et al., 2003). The DMN has been shown to have high RS metabolism (Raichle et al., 2001). Most previous studies mainly reported decreased connectivity in several DMN regions in patients with AD or aMCI compared with healthy individuals (Greicius et al., 2004; Rombouts et al., 2005; Sorg et al., 2007). Conversely, some studies showed several regions that showed increased functional connectivity in patients with aMCI compared with healthy individuals (Bai et al., 2009; Qi et al., 2010). Nevertheless, the progression of DMN connectivity in patients with aMCI or AD remains uncertain. Most of these studies were based on the comparison of only two groups (Greicius et al., 2004; Sorg et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007; Bai et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Qi et al., 2010). The alteration patterns of DMN connectivity in patients with AD, aMCI, and healthy individuals remain, therefore, poorly understood. Comparison of functional connectivity in DMN between three groups simultaneously may provide better information than studies that only compared between two groups in the analysis of the progression of dementia; it would provide alteration patterns of decreased and increased functional connectivity as the disease progresses from normal aging to aMCI and AD.

The purpose of our study was to investigate patterns of functional alteration in the RS DMN using independent component analysis (ICA) across the continuum from normal aging to aMCI and AD, and explore whether the differences in functional connectivity are associated with differences in cognitive ability. Thus, this study examined (1) altered functional connectivity of the DMN in patients with AD or aMCI compared with healthy individuals; and (2) whether the regions exhibiting altered functional connectivity varied with a well known score of disease progression, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score, in patients with AD or aMCI. The MMSE score can quantify general cognitive function and reflects the progression of dementia (Folstein et al., 1983). The evaluation of the relationship between functional connectivity of DMN and cognitive abilities (i.e., MMSE scores) may provide important information to understand how functional alterations in patients with aMCI or AD progresses over time.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Sixty-two healthy subjects (male/female ratio, 17/45; age, 68.5±8.0 years), 34 elderly patients with aMCI (18/16, 68.4±7.9 years), and 37 elderly patients with AD (10/27, 72.8±8.2 years) participated in this study. We obtained written informed consent, according to the Declaration of Helsinki, from all patients and controls and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea. Patients with aMCI met Petersen’s criteria for MCI, with the following modifications (Petersen et al., 1999): (1) subjective memory complaint by the patient or his/her caregiver; (2) normal general cognitive function above the 16th percentile on the MMSE; (3) normal activities of daily living (ADL), as judged by both an interview with a clinician and the standardized ADL scale described previously (Seo et al., 2007); (4) objective memory function decline below the 16th percentile on neuropsychological tests; and (5) no dementia. All patients with AD fulfilled the criteria for probable AD proposed by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS–ADRDA) (McKhann et al., 1984). The healthy control group consisted of 62 individuals who had no history of neurological or psychiatric illnesses and exhibited normal performance in the neuropsychological tests. All participants underwent clinical interviews and neurological examinations, as described previously (Seo et al., 2007). The demographic and clinical data of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical findings of healthy subjects, and patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI) or Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

| Healthy Subjects | aMCI | AD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Subjects | 62 | 34 | 37 |

| MMSE Score | 28.6±1.93 | 27.1±2.1 | 16.8±6.9 |

| Age | 68.5±8.0 | 68.4±7.9 | 72.8±8.2 |

| Sex (M/F) | 17/45 | 18/16 | 10/27 |

| Education | 10.9±5.2 | 11.5±5.2 | 10.9±5.3 |

Demographic and clinical finding of healthy subjects, and patients with aMCI or AD Data for age, Education and MMSE, mini-mental state examination, score: mean ± SD Data for sex, M: male, F: female

Significant differences were noted in MMSE scores (P<0.0001). The p-value was obtained by one-way analysis of variance test.

Data acquisition

All imaging was carried out at the Samsung Medical Center using a Philips Intera Achieva 3.0 Tesla scanner equipped with an 8-channel SENSE head coil (Philips Healthcare, the Netherlands). Whole-brain echo planar imaging (EPI) time-series scans (TR= 3s; TE = 35 ms; flip angle = 90°; 1.7 × 1.7 × 4 mm3 voxel resolution) consisted of 100 volumes and lasted for about 5 min. During each scan, participants were instructed to rest with their eyes open and fixate a crosshair that was centrally projected in white against a black background. A high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical image was also acquired using a magnetization-prepared gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence (TR = 9.9 ms; TE = 4.6 ms; flip angle = 8°; 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 mm3 voxel resolution).

fMRI data preprocessing

Imaging data were assessed and processed using AFNI (Analysis of Functional NeuroImages, http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni/) and FSL (FMRIB’s Software Library, www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) (Cox, 1996; Jenkinson & Smith, 2001; Jenkinson et al., 2002; Smith, 2002) software. EPI data were screened for head motion artifacts (Power et al., 2012) using the threshold level 0.3 mm for the Euclidean L2 norm of motion displacement per TR interval, which passed the sudden motion qualification of AFNI software. Head-coil artifacts were also visually checked by observing the contribution of local white matter signals in a time series, and no strong artifact was detected across brain tissue types (Jo et al., 2010). The first three volumes from each functional image were discarded to allow for the stabilization of the magnetic field. Subsequently, the slice timing and head motion of RS EPI time series were corrected and spatial smoothing was performed using a 6mm full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel and high-pass temporal filtering (Gaussian-weighted least-squares straight line fitting, with σ=100s). Preprocessed EPI data were aligned to the T1-weighted anatomical image and normalized to the MNI152 template space for each individual (Mazziotta et al., 2001).

Independent component analysis

To identify time series coherences across voxels or regions, probabilistic ICA was performed, as implemented in FSL’s Multivariate Exploratory Linear Optimized Decomposition into Independent Components (MELODIC) software (www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/melodic; Beckmann & Smith, 2004). MELODIC automatically estimates the number of components from each datum using the Laplace approximation to the Bayesian evidence of the model order (Minka, 2000; Beckmann & Smith, 2004). The whitened observations were decomposed into sets of vectors that described signal variation across the temporal (time courses) and spatial (maps) domains by optimizing for non-Gaussian spatial source distributions using a fixed-point iteration technique (Hyvarinen, 1999). The application of ICA to fMRI data allows the removal of high- and low-frequency artifacts (McKeown et al., 1998; Quigley et al., 2002). For each component, the z value reflected the degree to which the time series of each voxel was associated with one of the specific components. We used spatial differences across z values of each component to determine functional connectivity levels. Therefore, the alterations of “functional connectivity” refers to the spatial changes in z values of each component. All components were then transformed into stereotaxic space and resampled to a voxel dimension of 2×2×2 mm3. The chosen component of the DMN was selected from the independent components of each individual using a combination of manual and template-matching procedures (Greicius et al., 2004). The manual selection procedure has the advantage of being highly accurate, but it may be subject to human error and is a time-consuming process in which all components must be checked (Franco et al., 2009). The template-matching procedure has the advantage of reducing time and human error compared with manual selection procedure. The combination of manual and automated techniques might be the best approach for selecting the DMN component (Franco et al., 2009). For the template-matching procedure, a template of the DMN was developed based on the peak regions reported previously (Greicius et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2011). Each region in the template was a sphere with a radius of 5mm. The difference of the average z values of voxels between inside and outside the template was calculated for each component. Among the five components exhibiting the greatest differences, manual selection of one component was performed by two trained researchers (JHC and HSK). This selection was based on the functional connectivity of the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), prefrontal cortex, and inferior parietal lobule (IPL), which are assumed to be the core regions associated with the DMN (Buckner et al., 2008). Finally, the component selected by the raters was determined to be the DMN component.

Group comparisons

Intra- and intergroup analysis

To explore the within-group functional connectivity differences of the DMN patterns, a one-sample t test was performed on the individual normalized functional connectivity of DMN maps of each group. The significance threshold was set at uncorrected P<0.001 (|t|>3.46 (healthy subjects), >3.61 (aMCI), and >3.58 (AD)) with a cluster size>312mm3. An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to determine the differences of functional connectivity between the three groups using age, sex, and education as covariates. Using the AFNI’s AlphaSim program, Monte Carlo simulations were performed to control for Type I errors (parameters: individual voxel p-value=0.01, simulated 10,000 times iteratively, 6mm FWHM Gaussian filter width with a whole-brain mask). The AlphaSim program provides an estimate of the overall significance level achieved for various combinations of individual voxel probability thresholds and cluster size thresholds (Poline et al., 1997). We obtained a corrected significance level of Pα<0.05 (uncorrected individual voxel height threshold of P<0.01, F>4.776 with a minimum cluster size of 1,000 mm3). Subsequently, to examine the inter-group differences, post hoc two-sample t tests were performed between pairs of groups for voxel-wise statistics (corrected significant level of Pα<0.05).

Relationship between functional connectivity of DMN and MMSE scores

To investigate the relationship between the functional connectivity of DMN and disease progression in the patients, we performed multiple regression analysis between the functional connectivity and MMSE scores in each patient group. Age, sex, and education were entered as covariates in the regression analysis.

Results

Group comparisons

Intra- and inter-group analysis

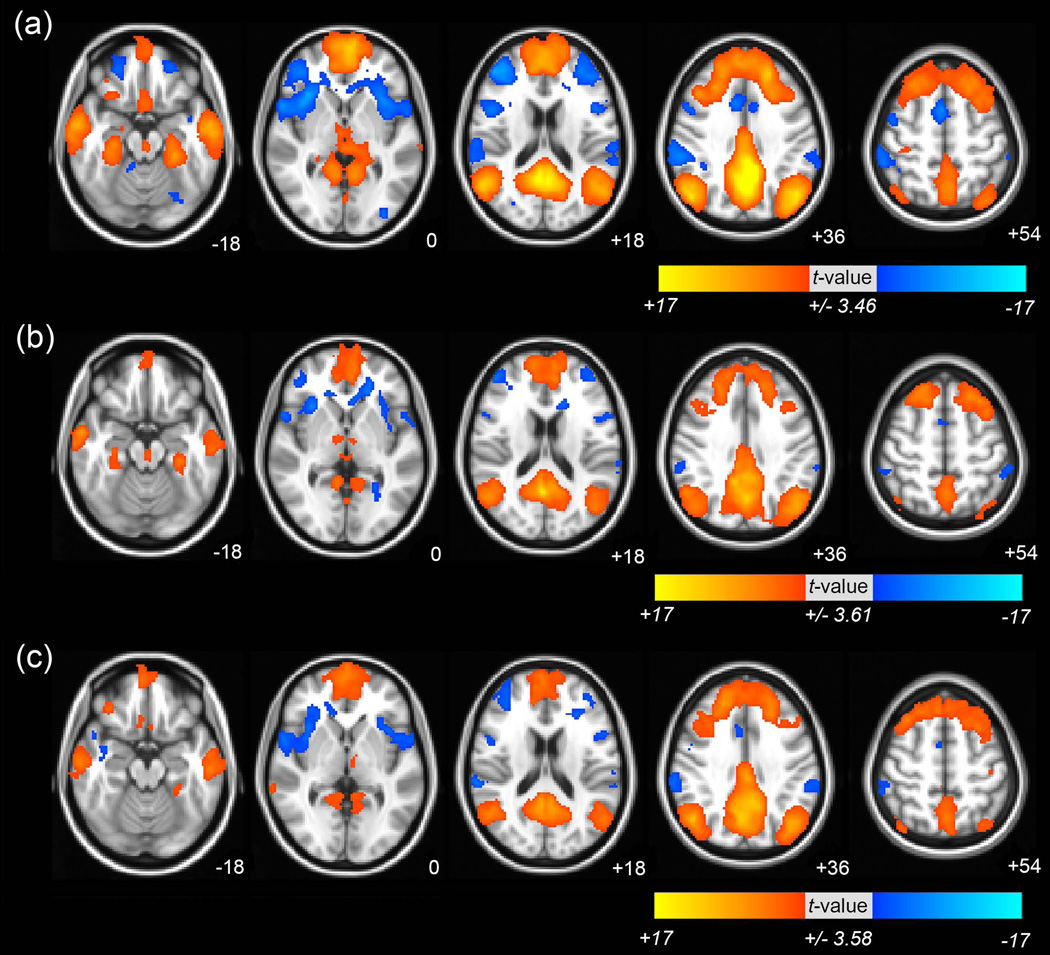

One-sample t test was used to generate group maps of DMN connectivity, including the PCC/precuneus, middle frontal gyrus (MFG), IPL, and middle temporal gyrus (MTG). The majority of DMN clusters were consistent across all groups (Fig 1 and see Supporting Information Table S1 for the details of clusters in DMN in all groups).

Fig 1. The functional connectivity of default mode network (DMN) in healthy subjects, and patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI) or Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Brain regions showed significant functional connectivity of DMN (a) in healthy subjects, (b) patients with aMCI (c) and patients with AD. The significance threshold was set at uncorrected P<0.001 (|t|>3.46 (healthy subjects), >3.61 (aMCI), and >3.58 (AD)) with a cluster size>312mm3. The images are oriented with the anterior side placed at the top and the left side placed to the right. The red and blue color represents positive and negative functional connectivity respectively.

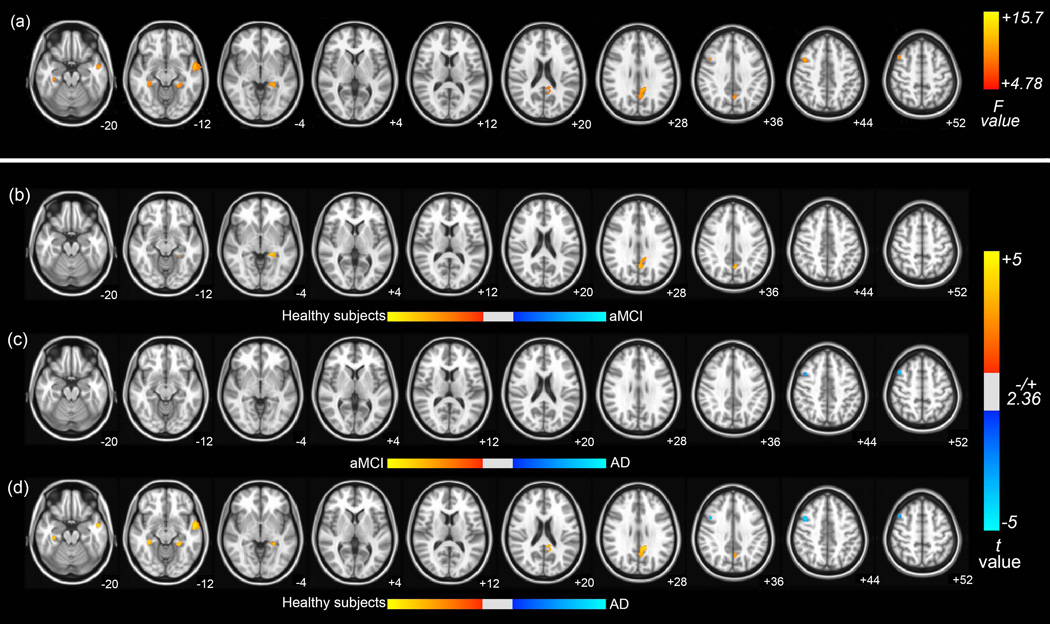

The results obtained from ANCOVA using age, sex, and education as covariates clearly showed significant differences in functional connectivity of DMN between the aMCI, AD, and healthy subjects groups. Significant group differences of functional connectivity in DMN were observed in the left PCC, left MTG, right MFG, and bilateral parahippocampal gyrus (PHG) with hippocampus at Pα<0.05 (AlphaSim corrected, uncorrected P<0.01 at a cluster size of at least 125 voxels; see Fig 2 (a) and Table 2 for a detailed list of the regions). Then, as shown in Fig 2 (b–d) and Table 3, we performed the post hoc two-sample t tests between pairs of groups in voxel-wise fashion with corrected Pα<0.05. Lower functional connectivity was found in patients with AD and aMCI compared with healthy subjects in the left PCC and left PHG. In addition, the functional connectivity in the left MTG and right PHG decreased in patients with AD compared with healthy subjects. Conversely, the increased functional connectivity in right MFG was found in patient with AD compared with patient with aMCI and healthy subjects.

Fig 2. Brain regions exhibiting significant differences in functional connectivity of DMN.

(a) Brain regions showed significant differences in functional connectivity of DMN between healthy subjects, patients with aMCI and patients with AD (Pα<0.05 (uncorrected P <0.01, F>4.78, 1000mm3, AlphaSim corrected)). The following were results of the post hoc two-sample t tests between pairs of the healthy subjects, patient with AD and aMCI groups in voxel-wise analysis. The significant differences in brain regions was found (b) in patients with aMCI compared with healthy subjects, (c) in patients with AD compared with patients with aMCI (d) and in patients with AD compared with healthy subjects (Pα<0.05). The images are oriented with the anterior side placed at the top and the left side placed to the right.

Table 2.

Brain regions with significant differences in functional connectivity of default mode network (DMN) between healthy subjects and in patients with aMCI or AD.

| Brain regions | R/L | Coordinates (mm) | Peak F values |

Voxels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | ||||

| Healthy subjects vs aMCI vs AD | ||||||

| PCC | L | −10 | −46 | 30 | 9.85 | 373 |

| MTG | L | −52 | −4 | −16 | 12.3 | 303 |

| MFG | R | 42 | 10 | 42 | 11.5 | 144 |

| PHG | R | 34 | −34 | −14 | 10.4 | 129 |

| PHG | L | −26 | −38 | −6 | 10.8 | 126 |

PCC: posterior cingulate gyrus, MTG: middle temporal gyrus, MFG: middle frontal gyrus, PHG: parahippocampal gyrus. Threshold: corrected Pα<0.05 (uncorrected individual voxel height threshold of P<0.01, F>4.776 with a minimum cluster size of 1,000mm3)

Table 3.

Results of post hoc two-sample t tests between pairs of groups of the healthy subjects, patient with AD and aMCI groups in voxel-wise analysis.

| Brain Regions | R/L | Coordinates (mm) | Peak t value |

Voxels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | ||||

| Healtdy subject vs aMCI | ||||||

| Precuneus | L | −4 | −62 | 38 | 3.46 | 244 |

| PHG | L | −20 | −36 | −4 | 3.96 | 84 |

| PCC | L | −16 | −42 | 14 | 3.11 | 7 |

| aMCI vs AD | ||||||

| MFG | R | 44 | 14 | 50 | −3.66 | 84 |

| Healthy subject vs AD | ||||||

| PCC | L | −10 | −46 | 30 | 4.17 | 355 |

| MTG | L | −52 | −4 | −16 | 4.91 | 295 |

| MFG | R | 42 | 10 | 42 | −4.75 | 137 |

| PHG | R | 34 | −34 | −14 | 4.55 | 124 |

| PHG | L | −26 | −38 | −6 | 4.2 | 103 |

PHG: parahippocampal gyrus, MFG: middle frontal gyrus, PCC: posterior cingulate gyrus, MTG: middle temporal gyrus. Positive values: Healthy subjects > aMCI, aMCI > AD, and Healthy subjects > AD; Negative values: aMCI > Healthy subjects, AD > aMCI, and AD > Healthy subjects; Threshold: corrected Pα<0.05

Relationship between functional connectivity of DMN and MMSE scores

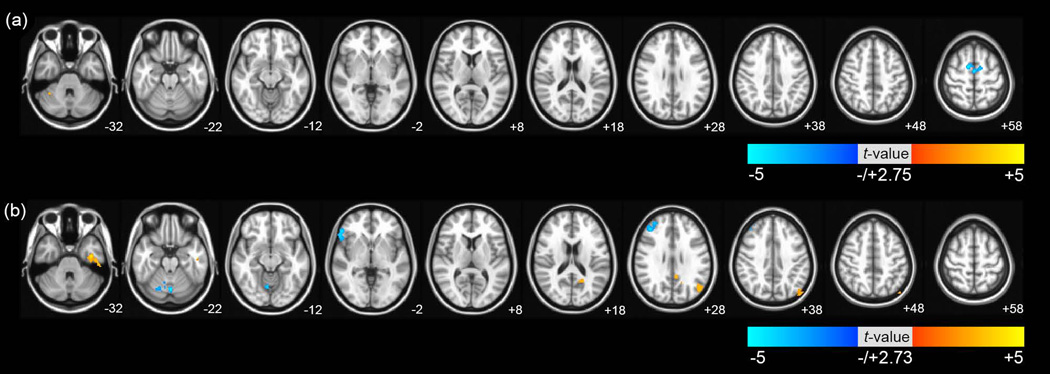

To evaluate the relationship between differences in functional connectivity of DMN and cognitive ability in the patients, we performed multiple regression analysis with age, sex, and education as covariates. In the aMCI group, as shown in Fig 3 (a), there was a significant negative correlation in the bilateral medial frontal gyrus and significant positive correlation in the cerebellum with corrected Pα<0.05. In the AD group, as shown in Fig 3 (b), there were significant positive correlations in the left IPL, left fusiform gyrus including MTG and left PCC. There were also significant negative correlations in the right MFG, inferior frontal gyrus, and cerebellum (corrected Pα<0.05). These results are presented in Table 4.

Fig 3. Brain regions exhibiting significant correlations between functional connectivity of DMN and mini-mental state examination (MMSE) scores in voxel wise analysis.

The brain regions which were significantly correlated by multiple regression analysis between the functional connectivity of DMN and MMSE scores (a) in the patients with aMCI, and (b) in the patients with AD. The significance threshold was set at corrected Pα<0.05 (uncorrected P <0.01, >2.75 (aMCI), and >2.73 (AD) with a cluster size>1000mm3). The images are oriented with the anterior side placed at the top and the left side placed to the right.

Table 4.

Results of multiple regression analysis between functional connectivity of DMN and mini-mental state examination (MMSE) score in patients with aMCI or AD in voxel wise analysis.

| Brain regions | R/L | Coordinates (mm) | Peak t value |

Voxels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | ||||

| aMCI | ||||||

| Medial frontal gyrus | L | 0 | −8 | 58 | −4.21 | 194 |

| Medial frontal gyrus | R | 10 | 0 | 60 | −4.9 | 123 |

| Cerebellum | R | 52 | −58 | −48 | 4.43 | 122 |

| AD | ||||||

| MFG | R | 42 | 38 | 30 | −4.07 | 272 |

| IPL | L | −48 | −78 | 46 | 4.02 | 252 |

| Cerebellum | L | 0 | −72 | −22 | −4.75 | 226 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | R | 54 | 34 | −2 | −4.21 | 211 |

| Fusiform gyrus | L | −38 | −12 | −32 | 4.67 | 207 |

| PCC | L | −6 | −48 | 28 | 3.65 | 131 |

MFG: middle frontal gyrus, PCC: posterior cingulate gyrus, IPL: inferior parietal lobule. Threshold: Pα<0.05 (uncorrected individual voxel height threshold of P<0.01 with a minimum cluster size of 1,000mm3)

Discussion

Our major findings were as follows: 1) both patients with aMCI and AD showed decreased functional connectivity in the left PCC and left PHG compared with healthy subjects. Furthermore, patient with AD had significantly decreased functional connectivity in the left MTG and right PHG. There was no significant decrease in functional connectivity in patients with AD compared with patient with aMCI; 2) patients with AD exhibited significantly increased functional connectivity in the right MFG compared with patients with aMCI and healthy subjects 3) in patients with aMCI, there were significant positive correlations in right cerebellum and negative correlations in bilateral medial frontal gyrus between functional connectivity of DMN and MMSE scores; and 4) patients with AD exhibited significant positive correlations in left IPL, left fusiform gyrus including MTG and left PCC and negative correlations in right MFG, left cerebellum and right inferior frontal gyrus between functional connectivity of DMN and MMSE scores. Taken together, our findings suggested that an increased functional connectivity in the right MFG might compensate for the loss of function in the PCC, MTG and PHG via compensatory mechanisms in cortico-cortical connections.

Decreased functional connectivity of DMN in patients with AD and aMCI

We found that patients with aMCI and AD had significantly decreased functional connectivity in the left PCC and left PHG including hippocampus compared with healthy subjects. These results are consistent with those of previous studies (Greicius et al., 2004; Bai et al., 2009; Qi et al., 2010; Binnewijzend et al., 2012), which showed that the connectivity of DMN, including the PCC and PHG, decreased in patients with AD compared with healthy individuals (Greicius et al., 2004; Binnewijzend et al., 2012) and that patients with aMCI exhibited decreased connectivity compared with healthy individuals, in the same regions (Bai et al., 2009; Qi et al., 2010). Previous studies demonstrated that the PCC/precuneus plays a pivotal role in the DMN (Fransson & Marrelec, 2008) and that the PCC is the region that shows metabolic abnormalities in early AD (Minoshima et al., 1997). Thus, our findings replicated previous results suggesting that patients with AD or aMCI might have decreased functional connectivity in DMN, especially in the PCC and PHG.

We also showed that functional connectivity in the left MTG was significantly different between patients with AD and healthy subjects. A previous study showed that there were structural changes in the temporal lobe between healthy subjects and AD patient group (Pennanen et al., 2004; Im et al., 2008). With structural changes in the temporal lobe, our results confirm a notable decrease in functional change in the temporal area in patients with AD.

We also showed that functional connectivity in the left PHG decreased in both patients with aMCI and AD compared with healthy subjects. On the contrary, the functional connectivity in the right PHG only decreased in the patients with AD compared with healthy subjects. In the patients with aMCI, the reduced functional connectivity in the left PHG can be related to the reduced functional connectivity between the left PHG and left PCC reported earlier (Sorg et al., 2007; De Vogelaere et al., 2012). Taken together, the decreased functional connectivity in the left PCC, left MTG and PHG with hippocampus could be a biomarker for identifying patients with aMCI and AD.

Increased functional connectivity of DMN in patients with AD and aMCI

Our second major finding was the presence of increased connectivity in the right MFG for patients with AD compared with patients with aMCI and healthy subjects. The MFG has been identified as an important region in the DMN (Buckner et al., 2008). In this region, some studies also found increased connectivity based on RS functional connectivity in patients with AD (Wang et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2009). A study of hippocampus-related connectivity during RS showed increased connectivity between the left hippocampus and the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in patients with AD (Wang et al., 2006). Another ROI study found that patients with AD had increased positive correlations within the prefrontal, parietal and occipital lobes (Wang et al., 2007). A PCC-related connectivity analysis also showed increased connectivity in the left frontal and parietal cortices (Zhang et al., 2009). In addition to the RS fMRI analysis, the increased event-related functional activity in prefrontal regions was also demonstrated in a PET based study (Grady et al., 2003). In normal aging, healthy elderly individuals exhibit increased activity in the frontal regions compared with healthy young individuals (Cabeza et al., 2002; Logan et al., 2002). Although many areas might exhibit increased connectivity, this has been reported mainly in the frontal region (see the Supporting Information Table S2 for reviews of previous studies on frontal regions in AD, aMCI, and various other categories).

Recently, it was shown that decreased and increased functional connectivity of DMN coexists in patients with aMCI compared with healthy individuals (Qi et al., 2010). Those authors suggested that the increased connectivity observed in patients might be due to a compensatory mechanism for the loss of cognitive function. This interpretation of this increased connectivity of DMN in patients with AD was reported in several studies, although it was not found in the analysis of connectivity using ICA. From the point of view of compensatory mechanisms, these findings suggest that increased functional connectivity in the right MFG may reflect compensatory recruitment after loss of functional connectivity in the left PCC, left MTG, and bilateral PHG including hippocampus.

Alternatively, the increased functional connectivity in the MFG may reflect an early aberrant excitatory response to Amyloid beta (Aβ) (Mormino et al., 2011). In elderly individuals, the task-related fMRI study reported a failure to deactivate the medial prefrontal regions during successful episodic memory encoding (Sperling et al., 2009). Those authors proposed that Aβ deposition might cause aberrant modulation in the frontal region, and it is possible that persistent activation reflects the aberrant spiking activity that has been observed in an in vitro model and may be excitotoxic (Palop et al., 2007). It is possible that compensatory responses may lead to downstream reduction in activity as neurons undergo excitotoxicity (Mormino et al., 2011).

Relationship between functional connectivity of DMN and MMSE scores

We found significant positive and negative correlations between functional connectivity in patients with AD and aMCI and the MMSE scores. In the AD group, we found that the functional connectivity in left PCC, left IPL and left fusiform gyrus including MTG correlated significantly with MMSE scores. The correlation in PCC was also reported in an RS fMRI analysis using a regional coherence method (He et al., 2007). It was reported that the resting metabolism in the PCC/precuneus measured using fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) was correlated with disease progress evaluated using MMSE scores (Salmon et al., 2000; Herholz et al., 2002; Buckner et al., 2005). This result supports the contention that AD-related changes in the DMN in the left PCC were associated with cognitive score, in particular with MMSE scores. The functional connectivity in left PCC and left MTG was correlated significantly with MMSE scores. Taken together, the functional connectivity in the left PCC and left MTG should reflect the progression of the disease in patient with AD.

In patients with AD, we found significant negative correlations between functional connectivity in the right MFG, left cerebellum and right inferior frontal gyrus and MMSE scores. The functional connectivity in frontal regions also exhibited negative correlations with MMSE scores in aMCI. Although several hypotheses about the increased connectivity in patients with AD and aMCI exist, our finding demonstrated that the negative correlations between the functional connectivity of frontal regions and MMSE scores provided further support for the compensatory hypothesis in frontal regions.

We performed additional correlation analysis using MMSE scores from pooling AD and aMCI patients, because aMCI refers to a transitional state between the cognition of normal aging and dementia. However, the results did not show much difference from the analysis using each patient (see Supporting Information Table S3, S4 and Figure S1 and S3).

Methodological considerations

Several previous DMN analysis studies used a masking procedure (Greicius et al., 2004; Rombouts et al., 2005; Sorg et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007). Using a masking procedure, authors have shown only decreased connectivity of DMN determined by the specific mask in patients with AD or aMCI. However, other studies did not use a masking procedure. A whole-brain analysis was performed in these cases (Wang et al., 2006; He et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2009; Qi et al., 2010), which revealed not only decreased, but also increased connectivity of DMN in patients with AD or aMCI. Based on these results, the difference between analyses using a masking procedure and a whole-brain analysis is a sensitive and important issue. In this study, we assumed the existence of increased connectivity in patients with AD or aMCI. Therefore, we performed the whole-brain analysis.

ICA potentially decomposes DMN co-activations into more than one component and physiological noise may be included in the component. Because of these problems, two expert researchers (JHC and HSK) carefully selected the components for each individual subject via visual inspection. As a result, although we did not check every component, there was no splitting of DMN connectivity among the five components exhibiting the greatest differences between template and component.

Other groups also studied the comparison of functional connectivity of DMN in healthy subjects, MCI, and AD (Rombouts et al., 2005; Binnewijzend et al., 2012). However, it was not adopting a resting-state DMN but deactivation states during visual encoding task and non-spatial working memory task (Rombouts et al., 2005). In addition, another study did not show differences between three groups (Binnewijzend et al., 2012). Some chose the ROIs based on the statistical results themselves, which leads to biased estimates (Kriegeskorte et al., 2009). We performed additional ROI-based analyses to confirm the voxel-based analysis results (see the Supporting Information Table S4, Figure S2, S3 and S4). While both analyses are almost the same, there are some differences in the findings. We believe that the differences are mainly due to the methodological issues such as smoothness or singal to noise ratio (SNR) in ROI masks. The principal explanation for the differences in left MTG and right MFG may come from the methodological differences.

The strengths or limitations of our study

The strengths of our study are its prospective setting. We adopted the standardized MRI imaging protocol and standardized phenotyping of cognitive impairments. However, there are some limitations. First, because we did not perform pathological studies, we were not able to exclude the possible inclusion of patients with other degenerative pathologies. Second, because of cross-sectional nature of our study, we could only suggest the differences in functional connectivity between healthy individuals, aMCI, and AD. A longitudinal study would have been better suited to investigate the progression of functional connectivity based on a compensation hypothesis. Therefore, a longitudinal study is required for better analysis of functional connectivity. Third, our results might be confounded by gray matter loss. To explore this issue further, we preformed voxel-based morphometry analysis (See the Supporting Information Figure S5). It would be ideal to quantify functional connectivity differences while controlling for the gray matter loss, but that analysis is rather difficult, since there are notable resolution differences between EPT and T1 images. We leave the important problem of exploring relationship between functional connectivity and gray matter density as future work. Nevertheless, our study is noteworthy because it is the first one to the best of our knowledge suggesting that an increased functional connectivity in the MFG might compensate for the loss of function in the PCC, MTG, and PHG including hippocampus via compensatory mechanisms in cortico-cortical connections.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that brain connectivity in the DMN was significantly different in patients with AD or aMCI compared with healthy subjects. The decreased functional connectivity in the left PCC and PHG with hippocampus could be a biomarker for identifying patients with aMCI and AD. The patients with AD exhibited significantly increased functional connectivity in the right MFG. In addition, our results showed that the functional connectivity in left PCC, left MTG and right MFG might reflect the progression of disease in patient with AD. Taken together, an increase in connectivity in the MFG may compensate for the loss of function in the PCC and PHG including hippocampus via compensatory mechanisms that occur in cortico-cortical connections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (2012-0008757). And this study was also supported by Korean Healthcare Technology R&D Project (A102065). Hang Joon Jo is supported by NIMH and NINDS Intramural Research Program of the NIH. Thanks for the helpful discussion of our paper, Ph.D. Martin Sarter and Dr. Doug Munoz.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

amyloid beta

- ADL

activities of daily living

- aMCI

amnestic subtype of MCI

- ANCOVA

analysis of covariance

- DMN

default mode network

- EPI

echo planar imaging

- fMRI

functional magnetic resonance imaging

- FWHM

full-width-at-half-maximum

- ICA

independent component analysis

- IPL

inferior parietal lobule

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- MELODIC

Multivariate Exploratory Linear Optimized Decomposition into Independent Components

- MFG

middle frontal gyrus

- MMSE

mini-mental state examination

- MPRAGE

magnetization-prepared gradient echo

- MTG

middle temporal gyrus

- NINCDS-ADRDA

National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association

- PCC

posterior cingulate cortex

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PHG

parahippocampal gyrus

- ROI

region of interests

- RS

resting-state

References

- Andrews-Hanna JR, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Lustig C, Head D, Raichle ME, Buckner RL. Disruption of large-scale brain systems in advanced aging. Neuron. 2007;56:924–935. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backman L, Andersson JL, Nyberg L, Winblad B, Nordberg A, Almkvist O. Brain regions associated with episodic retrieval in normal aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1999;52:1861–1870. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.9.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai F, Watson DR, Yu H, Shi Y, Yuan Y, Zhang Z. Abnormal resting-state functional connectivity of posterior cingulate cortex in amnestic type mild cognitive impairment. Brain research. 2009;1302:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann CF, Smith SM. Probabilistic independent component analysis for functional magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2004;23:137–152. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.822821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder JR, Frost JA, Hammeke TA, Bellgowan PS, Rao SM, Cox RW. Conceptual processing during the conscious resting state. A functional MRI study. Journal of cognitive neuroscience. 1999;11:80–95. doi: 10.1162/089892999563265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binnewijzend MA, Schoonheim MM, Sanz-Arigita E, Wink AM, van der Flier WM, Tolboom N, Adriaanse SM, Damoiseaux JS, Scheltens P, van Berckel BN, Barkhof F. Resting-state fMRI changes in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiology of aging. 2012;33:2018–2028. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookheimer SY, Strojwas MH, Cohen MS, Saunders AM, Pericak-Vance MA, Mazziotta JC, Small GW. Patterns of brain activation in people at risk for Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:450–456. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008173430701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch B, Bartres-Faz D, Rami L, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Fernandez-Espejo D, Junque C, Sole-Padulles C, Sanchez-Valle R, Bargallo N, Falcon C, Molinuevo JL. Cognitive reserve modulates task-induced activations and deactivations in healthy elders, amnestic mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer's disease. Cortex. 2010;46:451–461. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Evolution of the neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease. Acta neurologica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 1996;165:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1996.tb05866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain's default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Shannon BJ, LaRossa G, Sachs R, Fotenos AF, Sheline YI, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Morris JC, Mintun MA. Molecular, structural, and functional characterization of Alzheimer's disease: evidence for a relationship between default activity, amyloid, and memory. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25:7709–7717. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2177-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, Anderson ND, Locantore JK, McIntosh AR. Aging gracefully: compensatory brain activity in high-performing older adults. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1394–1402. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Computers and biomedical research, an international journal. 1996;29:162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vogelaere F, Santens P, Achten E, Boon P, Vingerhoets G. Altered default-mode network activation in mild cognitive impairment compared with healthy aging. Neuroradiology. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00234-012-1036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippini N, MacIntosh BJ, Hough MG, Goodwin GM, Frisoni GB, Smith SM, Matthews PM, Beckmann CF, Mackay CE. Distinct patterns of brain activity in young carriers of the APOE-epsilon4 allele. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7209–7214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811879106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The Mini-Mental State Examination. Archives of general psychiatry. 1983;40:812. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790060110016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco AR, Pritchard A, Calhoun VD, Mayer AR. Interrater and intermethod reliability of default mode network selection. Human brain mapping. 2009;30:2293–2303. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransson P, Marrelec G. The precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex plays a pivotal role in the default mode network: Evidence from a partial correlation network analysis. Neuroimage. 2008;42:1178–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, Petersen RC, Ritchie K, Broich K, Belleville S, Brodaty H, Bennett D, Chertkow H, Cummings JL, de Leon M, Feldman H, Ganguli M, Hampel H, Scheltens P, Tierney MC, Whitehouse P, Winblad B. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet. 2006;367:1262–1270. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould RL, Arroyo B, Brown RG, Owen AM, Bullmore ET, Howard RJ. Brain mechanisms of successful compensation during learning in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:1011–1017. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000237534.31734.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady CL, McIntosh AR, Beig S, Keightley ML, Burian H, Black SE. Evidence from functional neuroimaging of a compensatory prefrontal network in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23:986–993. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00986.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:253–258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135058100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Srivastava G, Reiss AL, Menon V. Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer's disease from healthy aging: evidence from functional MRI. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:4637–4642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308627101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamalainen A, Pihlajamaki M, Tanila H, Hanninen T, Niskanen E, Tervo S, Karjalainen PA, Vanninen RL, Soininen H. Increased fMRI responses during encoding in mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1889–1903. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Wang L, Zang Y, Tian L, Zhang X, Li K, Jiang T. Regional coherence changes in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease: a combined structural and resting-state functional MRI study. Neuroimage. 2007;35:488–500. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herholz K, Salmon E, Perani D, Baron JC, Holthoff V, Frolich L, Schonknecht P, Ito K, Mielke R, Kalbe E, Zundorf G, Delbeuck X, Pelati O, Anchisi D, Fazio F, Kerrouche N, Desgranges B, Eustache F, Beuthien-Baumann B, Menzel C, Schroder J, Kato T, Arahata Y, Henze M, Heiss WD. Discrimination between Alzheimer dementia and controls by automated analysis of multicenter FDG PET. Neuroimage. 2002;17:302–316. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyvarinen A. Fast and robust fixed-point algorithms for independent component analysis. IEEE Trans Neural Netw. 1999;10:626–634. doi: 10.1109/72.761722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im K, Lee JM, Seo SW, HyungKim S, Kim SI, Na DL. Sulcal morphology changes and their relationship with cortical thickness and gyral white matter volume in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. NeuroImage. 2008;43:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17:825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5:143–156. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo HJ, Saad ZS, Simmons WK, Milbury LA, Cox RW. Mapping sources of correlation in resting state FMRI, with artifact detection and removal. NeuroImage. 2010;52:571–582. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.04.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegeskorte N, Simmons WK, Bellgowan PS, Baker CI. Circular analysis in systems neuroscience: the dangers of double dipping. Nature neuroscience. 2009;12:535–540. doi: 10.1038/nn.2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan JM, Sanders AL, Snyder AZ, Morris JC, Buckner RL. Under-recruitment and nonselective recruitment: dissociable neural mechanisms associated with aging. Neuron. 2002;33:827–840. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00612-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig C, Snyder AZ, Bhakta M, O'Brien KC, McAvoy M, Raichle ME, Morris JC, Buckner RL. Functional deactivations: change with age and dementia of the Alzheimer type. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14504–14509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235925100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire EA, Vargha-Khadem F, Mishkin M. The effects of bilateral hippocampal damage on fMRI regional activations and interactions during memory retrieval. Brain. 2001;124:1156–1170. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.6.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazziotta J, Toga A, Evans A, Fox P, Lancaster J, Zilles K, Woods R, Paus T, Simpson G, Pike B, Holmes C, Collins L, Thompson P, MacDonald D, Iacoboni M, Schormann T, Amunts K, Palomero-Gallagher N, Geyer S, Parsons L, Narr K, Kabani N, Le Goualher G, Boomsma D, Cannon T, Kawashima R, Mazoyer B. A probabilistic atlas and reference system for the human brain: International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM) Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 2001;356:1293–1322. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown MJ, Jung TP, Makeig S, Brown G, Kindermann SS, Lee TW, Sejnowski TJ. Spatially independent activity patterns in functional MRI data during the stroop color-naming task. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:803–810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minka TP. Massachusetts Inst. Technol. Cambridge: Tech. Rep.; 2000. Automatic choice of dimensionality for PCA; p. 514. [Google Scholar]

- Minoshima S, Giordani B, Berent S, Frey KA, Foster NL, Kuhl DE. Metabolic reduction in the posterior cingulate cortex in very early Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:85–94. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mormino EC, Smiljic A, Hayenga AO, Onami SH, Greicius MD, Rabinovici GD, Janabi M, Baker SL, Yen IV, Madison CM, Miller BL, Jagust WJ. Relationships between beta-amyloid and functional connectivity in different components of the default mode network in aging. Cerebral cortex. 2011;21:2399–2407. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop JJ, Chin J, Roberson ED, Wang J, Thwin MT, Bien-Ly N, Yoo J, Ho KO, Yu GQ, Kreitzer A, Finkbeiner S, Noebels JL, Mucke L. Aberrant excitatory neuronal activity and compensatory remodeling of inhibitory hippocampal circuits in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2007;55:697–711. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariente J, Cole S, Henson R, Clare L, Kennedy A, Rossor M, Cipoloti L, Puel M, Demonet JF, Chollet F, Frackowiak RS. Alzheimer's patients engage an alternative network during a memory task. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:870–879. doi: 10.1002/ana.20653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennanen C, Kivipelto M, Tuomainen S, Hartikainen P, Hanninen T, Laakso MP, Hallikainen M, Vanhanen M, Nissinen A, Helkala EL, Vainio P, Vanninen R, Partanen K, Soininen H. Hippocampus and entorhinal cortex in mild cognitive impairment and early AD. Neurobiology of aging. 2004;25:303–310. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Archives of neurology. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poline JB, Worsley KJ, Evans AC, Friston KJ. Combining spatial extent and peak intensity to test for activations in functional imaging. Neuroimage. 1997;5:83–96. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. NeuroImage. 2012;59:2142–2154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Z, Wu X, Wang Z, Zhang N, Dong H, Yao L, Li K. Impairment and compensation coexist in amnestic MCI default mode network. NeuroImage. 2010;50:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley MA, Haughton VM, Carew J, Cordes D, Moritz CH, Meyerand ME. Comparison of independent component analysis and conventional hypothesis-driven analysis for clinical functional MR image processing. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:49–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter-Lorenz P. New visions of the aging mind and brain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6:394. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)01957-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rombouts SA, Barkhof F, Goekoop R, Stam CJ, Scheltens P. Altered resting state networks in mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer's disease: an fMRI study. Human brain mapping. 2005;26:231–239. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosano C, Aizenstein HJ, Cochran JL, Saxton JA, De Kosky ST, Newman AB, Kuller LH, Lopez OL, Carter CS. Event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation of executive control in very old individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:761–767. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon E, Collette F, Degueldre C, Lemaire C, Franck G. Voxel-based analysis of confounding effects of age and dementia severity on cerebral metabolism in Alzheimer's disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000;10:39–48. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(200005)10:1<39::AID-HBM50>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo SW, Im K, Lee JM, Kim YH, Kim ST, Kim SY, Yang DW, Kim SI, Cho YS, Na DL. Cortical thickness in single- versus multiple-domain amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage. 2007;36:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp. 2002;17:143–155. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorg C, Riedl V, Muhlau M, Calhoun VD, Eichele T, Laer L, Drzezga A, Forstl H, Kurz A, Zimmer C, Wohlschlager AM. Selective changes of resting-state networks in individuals at risk for Alzheimer's disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:18760–18765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708803104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Laviolette PS, O'Keefe K, O'Brien J, Rentz DM, Pihlajamaki M, Marshall G, Hyman BT, Selkoe DJ, Hedden T, Buckner RL, Becker JA, Johnson KA. Amyloid deposition is associated with impaired default network function in older persons without dementia. Neuron. 2009;63:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thulborn KR, Martin C, Voyvodic JT. Functional MR imaging using a visually guided saccade paradigm for comparing activation patterns in patients with probable Alzheimer's disease and in cognitively able elderly volunteers. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:524–531. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Liang M, Wang L, Tian L, Zhang X, Li K, Jiang T. Altered functional connectivity in early Alzheimer's disease: a resting-state fMRI study. Human brain mapping. 2007;28:967–978. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zang Y, He Y, Liang M, Zhang X, Tian L, Wu T, Jiang T, Li K. Changes in hippocampal connectivity in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease: evidence from resting state fMRI. NeuroImage. 2006;31:496–504. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Yan C, Zhao C, Qi Z, Zhou W, Lu J, He Y, Li K. Spatial patterns of intrinsic brain activity in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: a resting-state functional MRI study. Human brain mapping. 2011;32:1720–1740. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Li R, Fleisher AS, Reiman EM, Guan X, Zhang Y, Chen K, Yao L. Altered default mode network connectivity in Alzheimer's disease--a resting functional MRI and Bayesian network study. Human brain mapping. 2011;32:1868–1881. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K, Petersen RC, Lindquist K, Kramer J, Miller B. Subtype of mild cognitive impairment and progression to dementia and death. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders. 2006;22:312–319. doi: 10.1159/000095427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yetkin FZ, Rosenberg RN, Weiner MF, Purdy PD, Cullum CM. FMRI of working memory in patients with mild cognitive impairment and probable Alzheimer's disease. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:193–206. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2794-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HY, Wang SJ, Xing J, Liu B, Ma ZL, Yang M, Zhang ZJ, Teng GJ. Detection of PCC functional connectivity characteristics in resting-state fMRI in mild Alzheimer's disease. Behavioural brain research. 2009;197:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.