Abstract

To effectively intervene with overweight and obese youth, it is imperative that primary care providers and behavioral interventionists work in concert to help families implement healthy behaviors across socioenvironmental domains (i.e., family/home, peer, community). As health care providers are often the first line of intervention for families, one critical component to implementing the socioenvironmental approach is to infuse intervention strategies into the primary care setting. In this paper, we review current office-based counseling practices and provide evidence-based recommendations for addressing weight status and strategies for encouraging behavior change with children and families, primarily by increasing social support. By providing such collaborative, targeted efforts, consistent health messages and support will be delivered across children’s everyday contexts, thereby helping youth to achieve successful implementation of eating and activity behaviors and sustainable weight loss outcomes.

Keywords: pediatric obesity, socioenvironmental, office-based approaches, health care professionals, lifestyle interventions

The obesity epidemic has reached epic proportions in the United States (US).1,2 Approximately 70% of US adults3 and 32% of children are overweight or obese.1 For children and adolescents, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention defines overweight as a body mass index (BMI: weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) between the 85th and 95th percentiles and obesity as a BMI at or above the 95th percentile for sex and age.4 The BMI scores and specified percentile distributions are easy and feasible to obtain and serve as indirect measures of body fat.5 Overweight and obesity are associated with chronic health conditions, heightened psychological distress, increased medical costs, and reduced quality of life.6–10 In fact, as children get heavier, their risk for health problems, such as metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, directly increases, as well.6,11 Early intervention is essential, as elevated childhood height and BMI are robust predictors of young adult BMI,12 and findings show that children with a BMI above the 85th percentile are more likely to continue to gain weight and to become overweight or obese in adolescence than normal weight children.13 While many assume that children will simply grow out of their overweight or obese status, the reality is that childhood overweight and obesity are critical risk factors for overweight and obesity in adulthood,14 and risk of developing obesity later in life increases with child age and BMI.13,14 The tendency for overweight or obesity to track across the lifespan starts as young as 9 months and necessitates early intervention, as pediatric overweight and obesity do not spontaneously resolve with age.15,16 List 1 provides key reasons why childhood is an ideal point of intervention;16 in fact, even small weight loss reductions are sufficient for overweight and obese children to satisfy criteria for normal weight.17

The US Preventive Task Force recommends that overweight and obese children receive specialty treatment of moderate-to-high intensity that includes counseling and other interventions to target diet and physical activity; in addition, parents are expected to play a pivotal role in treatment.18 A collaborative effort between primary care providers (PCPs) and behavioral interventionists is necessitated to provide consistent health messaging and support for successful weight loss and prevention of excess weight gain. Finally, social support is the ultimate driver of sustainable behavior change; it is imperative to promote social facilitation within interventions for pediatric obesity.

The purpose of this paper is to 1) discuss current practices and limitations for weight loss intervention in health care settings; 2) describe family-based behavioral interventions and outcome predictors; 3) review successful behavior change strategies for weight loss maintenance and the components of family-based behavioral interventions applied within a socioenvironmental approach; and 4) discuss recommendations for how to best utilize the office environment as a critical point for obesity prevention and treatment across socioenvironmental domains.

Overview of office-based counseling approaches: Current Practices

Extending pediatric obesity interventions into common practice relies on identification of settings in which effective programs can be integrated. The health care office environment is ripe for intervention deployment, as PCPs routinely meet with children and families, can screen for obesity and heightened weight status, and are often the first line of care. In 2003, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published expert guidelines for the screening and monitoring of pediatric obesity.19 This report encourages PCPs to track BMI percentile and promote healthy eating and activity behaviors. In 2007, the guidelines were updated with more intensive recommendations for obesity treatment and prevention.5

A significant proportion of PCPs report being unaware of these guidelines20 or do not report regular implementation.21 Some providers are able to incorporate the recommendations into practice,21 especially following training,22 although it is unclear whether PCPs sustain these behaviors in the long term.23 Among PCPs who used current criteria for identifying overweight or obese children, many reported concerns that they lacked adequate skills to address the problem,24 their counseling was ineffective, or adequate treatment strategies do not exist.21,25–27 One study found that nearly all PCPs used visual assessment to determine children’s obesity status, but only half actually computed BMI percentile.21,26 Results from a separate survey revealed that the majority (71%) of PCPs engaged in discussions with families about increasing overweight or obese children’s healthy behaviors, but few (19%) provided families with the necessary tools to implement the changes, although only a limited number of providers followed up with families about their behavior changes.24 Finally, in studies that report on children’s weight change outcome as a result of brief provider counseling, findings generally point to nonsignificant reductions in BMI.28–31

However, despite a lack of weight change, some PCP interventions have led to increased healthy behaviors (e.g., improved nutrition and physical activity patterns).32,33 In sum, there is promise that PCPs are able to successfully incorporate behavior change principles into practice; given that effective intervention methods have been established but not implemented into routine care, there is a need for a more targeted, intensive approach that unifies families, providers, and behavioral interventionists.22

Understanding motivation in parents

Identifying families in need of intervention, connecting them with appropriate services, and checking on their progress represent central roles of PCPs. To maximize the integration of care across settings, it is ideal for PCPs to engage parents in conversations to assess their motivation and to evaluate their current needs and resources.

Given their crucial role in child weight loss success, it is important to address parents’ confidence in their ability to do well in a weight loss intervention.34,35 Gaining an understanding of parent motivation may be particularly relevant for PCPs, as some rate “lack of parental involvement” as a common barrier to pediatric obesity treatment.24 A recent study assessed three components of motivation: readiness (to change a specific behavior), importance (of making the change), and confidence (in their ability to make the change).34 Parental confidence was the strongest predictor of treatment completion and child weight loss. Braet and colleagues showed that parents’ motivation at baseline predicted treatment completion.35 Additionally, an intervention designed to increase and maintain motivation for continued weight loss behaviors was efficacious.36 Thus, it may be useful to assess and increase parents’ motivating factors to optimize their likelihood of completing treatment and losing weight; motivational interviewing skills (e.g., reflective listening and a non-judgmental stance) can be used to help individuals assess the benefits and drawbacks to a decision and make a positive choice towards behavior change.

Specifically, providers can talk with parents to learn what is reinforcing to them about losing weight and their ability to implement the intervention strategies.37 Questions such as, “What concerns do you have about your family’s ability to implement healthy behaviors in the home?” can help parents to articulate their motivation and readiness for participation in a weight loss intervention.5 Second, providers are encouraged to help parents to map out a network of support by identifying individuals in their social circle, as well as peers and caretakers in their children’s social circle, who will support or possibly hinder their weight loss efforts. Capitalizing on supportive resources will be helpful to families in the long term. Finally, it is important to discuss potential barriers to treatment success with parents (e.g., busy schedules, lack of motivation, previous weight loss failures). This dialogue will identify strategies to increase and maintain families’ motivation throughout the intervention.

Predictors of sustainable behavior change for pediatric obesity

Once providers identify families in need of intervention, it is imperative to choose effective intervention strategies, as well as to consider specific factors that predict outcome.

Family-based behavioral lifestyle interventions

Lifestyle interventions are active treatments that modify overweight and obese children’s daily practices (e.g., improved dietary intake and physical activity); by capitalizing on daily living, behavior changes are better sustained over time.38 A lifestyle intervention utilizes an organic strategy in which behavioral goals are tracked and made progressively more comprehensive, and families learn to problem-solve barriers. Providers can encourage patients to meet with a specialist and participate in a behavioral weight loss program that emphasizes weekly monitoring, skill-building, goal-setting, and evaluating progress over time. Such a comprehensive approach is in contrast to an education-only intervention condition, in which information is presented to families to help them make changes. Numerous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses have shown that active lifestyle interventions are superior to no-treatment control or education-only conditions39 (Table 1). A recent meta-analysis found that lifestyle interventions yield an average decrease in percent overweight of 8.9%, compared to education-only controls that yield an average increase of 2.7% at follow-up.39

Table 1.

Recent reviews and meta-analyses of pediatric weight loss studies

| Author | Type of Review and Number of Studies | Target Population | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Dietetic Association (2006) | Review of 29 RCTs and 15 other types of studies | Overweight children (ages 2 through 12) and adolescents (ages 13 through 18) | Positive effects for multi-component, family- based programs especially for children ages 5 through 12 |

| Latzer et al. (2008) | Review of 80 articles | Overweight children and adolescents (ages 2 to 19) | Behavioral modification strategies have a modest, short-term efficacy; family and parents improve treatment outcome |

| McGovern, et al. (2008) | Meta-analysis of 61 randomized trials | Overweight children and adolescents (ages 2 to 18) | Small to moderate treatment effects of combined lifestyle interventions on BMI |

| Snethen et al. (2006) | Meta-analysis of 7 interventions | Overweight children (ages 6 to 16 with an overall mean age not older than 12) | Multi-component lifestyle interventions that include parental involvement can be effective in assisting children to lose weight |

| Tsiros et al. (2008) | Review of 34 RCTs | Overweight or obese adolescents (ages 12 to 19) | Lifestyle interventions with behavior/cognitive- behavioral components are promising particularly for long-term maintenance |

| Wilfley et al. (2007) | Meta-analysis of 14 RCTs | Overweight youth (ages 19 or younger) | Lifestyle interventions produce significant changes in weight status in the short-term with encouraging results for the persistence of effects |

Family-based behavioral weight loss treatments (FBTs) are lifestyle interventions that are typically regarded as the first line of treatment for childhood overweight and obesity due to their empirically-demonstrated efficacy40–46 and relative safety, compared to pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery.41 Recent work indicates that children receiving a multi-component FBT demonstrated significant decreases in percent overweight and improvements in related comorbidities, whereas those receiving usual care did not exhibit changes in percent overweight.47 Furthermore, positive outcomes of FBT are not limited to changes in child weight; this approach produces significant reductions in blood pressure and cholesterol levels,48 as well as psychosocial health benefits.49–51

The importance of parental involvement

The rationale for parental involvement in treatment is two-fold. Parental obesity has been identified as a significant risk factor for childhood obesity,52 with one study reporting that children with obese parents are at a two- to three-fold increased risk for being obese themselves in adulthood.14 This concordance of parent-child weight status, likely due to shared genetic and environmental factors, suggests a strong parental influence on the weight status of their offspring and could have a powerful positive impact in FBTs. Secondly, FBTs recognize that the children’s weight-related behaviors are developed and maintained within the context of the family;53 therefore, lifestyle interventions aim to capitalize on the influence parents can employ over the weight-related behaviors of their young children and the structure of the family environment.54,55

Parents or caregivers are necessary partners in pediatric weight loss55,56 due to their role as key agents of change and the impact of parent behavior change on child weight outcomes. Parents are conceptualized in a “helper” or “facilitator” role and taught to encourage children to exercise and make healthy choices, as well as to modify the shared home environment.54 Parental involvement is supported by behavioral economics theory, which suggests that individuals will choose behaviors that are less effortful and highly reinforcing. Therefore, inducing child behavior change is contingent upon parents providing healthful, reinforcing alternatives while limiting access to less healthy options. Social cognitive theory57 also provides a strong argument for parental inclusion in treatment, as it posits that modeling is a potent contributor to intervention success because children learn through observing their parents’ behaviors. In addition, the benefits of parents and children modeling healthier behaviors in the shared home environment may generalize to at-risk siblings.42 Overall, harnessing parental influence has the potential to improve the weight status of the entire family by creating an environment that supports healthy lifestyles. In summary, the most effective interventions for pediatric obesity incorporate multiple components and hinge upon parental involvement.

In addition to utilizing the evidence-based approaches shown to elicit successful weight loss in youth, it is important for providers to be mindful of key factors that predict sustainable behavior change and address them accordingly (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Specific predictors of sustainable behavior change.

| Predictor | Intervention Target |

|---|---|

| Children’s Early Treatment Response |

|

| Parents’ Treatment Response |

|

| Social Functioning |

|

| Built Environment |

|

| Poor Satiety Responsiveness |

|

| High Food Reinforcement |

|

| Binge or Loss of Control Eating |

|

| Impulsivity |

|

Early Treatment Response for Children

Sustainable behavior change is associated with early treatment response; specifically, recent work highlights that children who lose weight by week eight of a weight loss intervention have the greatest likelihood of sustained success.58 It is important for providers to encourage weight loss early in the intervention to maximize the potential for long-term success.

Treatment Response for Parents

Children whose parents respond to treatment are more likely to perform well in a weight loss intervention.59 Parents and caregivers play a pivotal role in treatment success,60 in that they serve as role models and are most often in charge of household decisions; they have the greatest capacity to implement treatment strategies and provide stimulus control.61 Thus, providers will ideally encourage parents and caregivers to actively engage in their own healthy behavior changes along with their children to ensure that children are receiving optimal support for healthful eating and activity.

Social Functioning

Heightened social problems (e.g., loneliness, jealousy, susceptibility to teasing) predict greater weight regain after FBT.62 In addition, children with higher levels of social problems evidence poorer weight loss maintenance.63 Youth who experience social problems or rejection may be more likely to use food as a coping mechanism64 and less likely to engage in physical activity.65 Obese children are less likely to join teams and physical activities and are more likely to experience concerns about physical competence65 and be perceived as less athletic than non-obese peers.66 Identifying children with social problems will allow providers to effectively tailor treatment goals, as well as help families to develop social support for sustainable behavior change.63

Built environment

Specific aspects of the built environment are associated with increased rates of obesity. including limited accessibility to parks and open spaces and increased accessibility to fast food restaurants.67,68 Recent research suggests that the built environment impacts children’s weight loss success in FBTs; access to parks and open spaces predicted greater weight loss success at two-year follow-up, whereas reduced access to parks and greater access to supermarkets and convenience stores predicted poorer outcome69. Thus, it is important for providers to consider the built environment when identifying intervention goals and determining how to best capitalize on available resources.

Appetitive Traits

When examining predictors that enhance sustainability, it is equally important to consider factors that increase vulnerability to weight gain and therefore may be barriers to weight loss. Appetitive traits, such as poor satiety responsiveness,70–72 high food reinforcement,73 binge or loss of control eating,74,75 and impulsivity,76 are heritable factors associated with increased energy intake, excess weight gain, and obesity risk among youth and adults.24,77–86 The presence of these traits may hinder treatment response, and as a result, addressing these weight-related liabilities through early detection and targeted intervention is critical. The primary mechanism for addressing these traits is training parents to help their children by shifting the environment and teaching them critical skills related to eating. Overall, PCPs should encourage parents of children who have difficulties in these domains to help their children to 1) regulate their portion sizes; 2) delay gratification for food (e.g., limit access to unhealthy foods to decrease temptation); 3) differentiate between hunger and emotional states; and 4) seek alternate activities other than eating if they are not hungry. Using stimulus control will enhance children’s potential for success, as well.

In sum, encouraging early treatment response and parent response, inquiring about social functioning and associated problems, capitalizing on resources in the built environment, and identifying and targeting appetitive traits will maximize treatment success and the long-term sustainability of these results. The presence of any of these factors indicates vulnerability for continued weight gain and need for higher intensity treatment; providers are encouraged to increase the frequency of visits for families who present with these identified factors.

Behavioral modification techniques that work across the socioenvironmental contexts

Intervening within a socioenvironmental framework

Interventions that utilize a socioenvironmental approach are efficacious for weight loss because they extend the focus of behavior change beyond the individual to encompass the home, peer, and community contexts.87–89 Interventions are most potent when embedded within the contexts of parents and children’s lives (i.e., where they live, learn, play), and when they devote sufficient time to the mastery and practice of strategies for implementing healthful behaviors.90 Given the ease with which old behavior patterns are cued, interventions need to be intensive enough and facilitate repeated practice across contexts so that newly-learned patterns become ingrained and entrenched.

Unhealthy eating and activity patterns have increased, and rapid changes in our diet over the past 200 years have led to significant increases in consumption of highly-processed foods and refined grains, sugars, and fats.91 Messages encouraging unhealthy choices are ubiquitous in our culture, such that children are barraged with obesogenic cues. Children repeatedly see billboards for fast food, walk near desserts for lunch in the cafeteria, and receive packaged sweets and juice after sports games. Promotion of physical activity has decreased: excluding gym class from the curriculum is a common response to budget cuts and the convenience of handheld video game devices gives way to increased sedentary activity. Given the myriad environmental prompts, weight loss is an uphill battle; individuals may be able to lose weight, but they often have difficulty sustaining these effects.92 Thus, the cross-contextual approach of the socioenvironmental model optimizes treatment success because it addresses eating and activity cues and behaviors across contexts and brings the family and social network together to support individuals as they make healthy behavior changes. For example, parents aiming to increase the availability and range of healthy meal options would first be prompted to have a conversation with their children and family members about offering healthy meal options at home. Parents would then be encouraged to talk with friends about serving healthy meal options during get-togethers with their children or themselves. In addition, parents would be advised to advocate with co-workers so that healthy meal options are offered in office settings and with school teachers so that healthy meal options are served in the classroom. Finally, parents would be encouraged to solicit support from organizers of community events (e.g., Girl/Boy Scout troop leader, person responsible for food after a community-based run) to offer healthy food options. This example of comprehensive support across levels demonstrates how families may maximize opportunities for increasing healthy default options. As families become more adept at implementing these strategies, they become increasingly empowered to extend their healthy behaviors into new situations.

In a standard behavioral weight loss intervention, the treatment emphasis and responsibility for behavior change are placed solely on the individual. The socioenvironmental model increases the duration and extends the scope of standard behavioral weight loss treatment by focusing on practicing skills and infusing support across contexts. This framework encourages behavior change via continued practice of newly-learned behaviors throughout a variety of settings. In standard behavioral weight loss intervention, individuals are encouraged to increase their daily physical activity (e.g., go for a run); the socioenvironmental approach builds on this by promoting that individuals engage in physical activities such as joining sports teams at school, doing physical activity fitness classes with friends, and training for community-based runs (e.g., 5-kilometer events) with their family. Beyond relying on individual willpower and self-regulatory skills, utilizing the socioenvornmental framework promotes an increased awareness of environmental cues and advocacy for making sustainable healthful changes. For instance, parents will be able to recognize that their usual drive home contains many fast food restaurants that prompt their children to ask for snacks and will be able to select an alternate route to avoid the prompts altogether. Recent evidence supports this approach as a strategy to achieve sustainable weight loss in children and adults.63,87,88,93 Given that weight regain is common following standard treatment,92,94,95 efforts to reverse the obesity epidemic hinge on incorporating these targets into weight loss interventions.

In the first assessment of the socioenvironmental model delivered in a family-based format, Wilfley and colleagues found that this approach, based on social facilitation of healthy behaviors, was associated with sustained weight loss compared to a behavioral weight loss intervention and control condition.63 More recently, biosimulation modeling revealed that an intervention with a socioenvironmental framework of increased duration (e.g., 1 year) will likely yield better weight loss maintenance over the long term.93

The application of the socioenvironmental intervention in clinical settings will provide necessary encouragement of healthful behaviors so that children receive more integrated messages and support for weight loss. 96 Given their role in treating children and discussing health-related targets with families, providers can work in concert with public health and community initiatives to educate, support, and follow up with families about behavior change implementation. The breadth of the obesity epidemic warrants that individuals across the health care profession actively engage in interventions to combat this problem.

Applying the socioenvironmental approach

Several behavioral modification techniques are effective in promoting healthy weight control within each context across the socioenvironmental domains (i.e., family/home, peer, and community). List 2 provides recommendations from the AAP regarding PCP behaviors to implement within the primary care setting, as well as specific energy balance behaviors for PCPs to recommend to families.5 As health care offices infuse these changes in routine clinical practice, it is recommended that an evaluation system becomes established to measure how effectively providers are incorporating these changes.

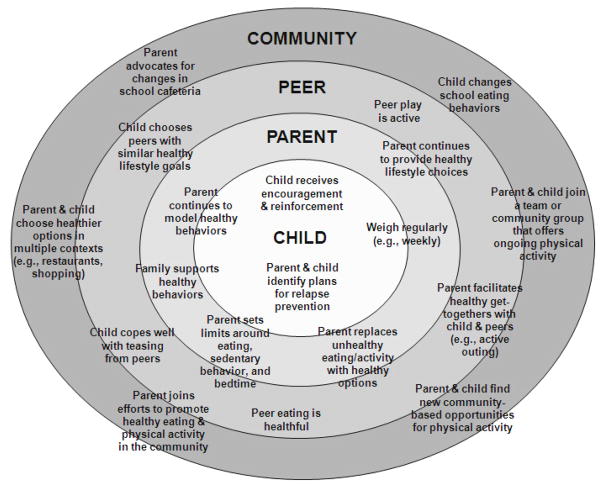

Figure 1 depicts specific health behaviors across the socioenvironmental domains that PCPs can help families to implement. Although these strategies focus on pediatric approaches, they are applicable across the age spectrum. As families begin to infuse these changes across their everyday contexts, providers should remind parents and children that progress may be gradual. Supportive, yet persistent, monitoring and praise will help families continue to stay on track with their behavior change goals.

Figure 1.

Socioenvironmental model and recommendations for providers to make across domains.

Family/Home Context

The socioenvironmental approach encourages families to implement behaviors and solicit social support in each relevant context. Table 3 provides a detailed list of specific behaviors providers can discuss with parents to facilitate sustainable weight loss. Within the family/home context, it is critical for families to monitor their eating and activity behaviors. Full monitoring, or the use of food and exercise diaries to document energy consumption (i.e., caloric intake) and energy expenditure (i.e., 10-minute bouts of activity), is helpful for identifying current behaviors and determining areas for improvement. Awareness is crucial for behavior change; for instance, full monitoring will reveal sources of excess energy intake or misconceptions about the healthfulness of the foods consumed, thereby allowing clinicians and families the opportunity to alter these behaviors.

Table 3.

Parental involvement in family-based behavioral interventions

| Supporting Healthy Eating Behaviors | Supporting Physical and Lifestyle Activity | Supporting Healthful Behavior Change |

|---|---|---|

Increase low-energy density foods

Decrease high-energy density foods

Improve meal patterns

|

Increase physical activity

Increase lifestyle activity

Decrease time spent in sedentary behaviors

|

Use behavior modification strategies

Target changes in the parent

Provide support for child

|

Weight loss is achieved during a state of negative energy balance, or when energy expenditure is greater than energy consumption. As described in List 1, healthy eating behaviors, such as increased fruit and vegetable consumption and decreased portion sizes, as well as improved activity patterns are key components of effective weight control interventions.97 Given that providers have limited time in session to distill information to families, easy-to-explain tools are helpful, particularly for children. For example, the Traffic Light Plan (TLP)49 is a user-friendly guide that codes foods and activities into RED, YELLOW, or GREEN categories. The TLP encourages children and families to limit RED foods, which are low-nutrient, energy-dense foods high in fat and/or sugar, and RED activities, which are sedentary behaviors that do not burn calories (e.g., “screen” time leisure activities, such as watching television, playing videogames, talking/texting on the phone, or using the computer). Furthermore, the TLP promotes the replacement of RED foods and activities with GREEN foods, which are healthful, nutrient-dense foods low in fat and calories, and GREEN activities, which are moderate-to-intense physical activities).

Another critical monitoring skill to promote within the family/home context is regular weighing (e.g., at the same time each week) to keep track of the families’ weight trajectory. Weight measurements provide important, objective data regarding their recent behaviors. Families can also get into the habit of having conversations about connecting behaviors to weight change, which is an important, evaluative skill.

To help children achieve a negative energy balance, parenting behaviors are crucial. It is recommended that providers work with parents to routinely implement the following strategies:

Modeling: Parents demonstrate how to make healthy choices and thus serve as models to their children, family members, friends, and community members.

Stimulus Control: It is necessary for parents to remove prompts for unhealthy foods and activity equipment (e.g., removing chips and cookies from the home or from within easy reach for children, keeping videogame equipment on a high shelf in the closet) and increase the availability of prompts for healthy foods and activity (e.g., placing fruits in a basket on the kitchen counter, keeping sneakers by the door) in the home.

Limit-Setting. Parents can set house rules to target reduction of specific behaviors, such as amount of unhealthy foods consumed or time spent watching television. This structure helps families to establish healthy patterns around eating (e.g., planning for and eating breakfast, lunch, dinner, and 1–2 snacks every day), activity (e.g., incorporating a daily walk after dinner), and sleep (e.g., setting “electronic curfews,” the time by which all electronics must be turned off, and bedtimes).

Clinical skills also include helping parents to problem-solve barriers to behavior implementation and identify plans for high-risk situations (e.g., an upcoming birthday party that will only serve unhealthy foods). In addition, it is important to recommend to parents that they establish a “no tolerance” policy for teasing and an open environment for healthful discussions about body image, as these represent common issues for overweight or obese youth.8,66,98–101

Inherent within behavior modification strategies is the identification of goals. Providers can help families accomplish their goals consistently by encouraging them to establish a system of reinforcement. Use of a behavioral rewards system is effective for reinforcing weight loss and attainment of healthy behaviors.102 However, it is important to ensure that reinforcement patterns encourage healthy behaviors, as this is not always the case. For instance, when parents reward children with dessert or only spend time with them while watching television, they are reinforcing unhealthy choices. Instead, explaining to parents that they should reward children with alternate, non-food reinforcers (e.g., activities they like to do or social events, such as going swimming, instead of candy or television shows) will promote the implementation of healthful behaviors. Praise is also a powerful reinforcer for positive behaviors. Thus, PCPs are encouraged to remind families to use reinforcement techniques to replace unhealthy behaviors with healthier options, which will ultimately help them to establish sustainable changes.

Peer Context

The peer context provides unique opportunities for intervention, given that friends are important sources of social support, both as models of healthy eating and sources of alternate reinforcement. Studies demonstrate that overweight and obese children are more likely to make healthy eating choices when they are with peers who make healthy choices.103–105 In addition, spending time with friends is a viable alternative to other types of reinforcers, including eating unhealthy foods.106 To reduce the amount of food children eat and provide an alternate reinforcer, providers should encourage parents to schedule active, healthy get-togethers with their children’s peers, capitalizing on friendships with peers who already do healthy behaviors. Clinicians can also help families to develop advocacy plans for peers, such as only serving healthy options at events and asking friends to make healthy foods, as well. As is critical within the family/home context, providers should recommend to parents that they promote a healthy environment with friends in terms of teasing (e.g., establish a “no tolerance” policy for teasing).

Community Context

Within the community context, families should be encouraged to utilize available resources and advocate for improved healthful options. For instance, clinicians can help families to become aware of neighborhood facilities and services, such as through the local community center, that promote healthy behaviors. Joining a physical activity-oriented team or club offers multiple benefits, including increased time spent being physically active, identification of a network of peers who engage in physical activity that is of interest to the child, and development of an alternate reinforcer to eating or sedentary behavior. Families should be encouraged to avoid unhealthy restaurants (e.g., fast food) or other venues in which it is difficult to make healthy choices. As families become more skilled in implementing these changes, they should also be encouraged to advocate for healthful changes in the local community regarding eating (e.g., serving skim milk at school or low-fat deli sandwiches as work) and activity (e.g., vigorous intensity games during gym class or access to stairs in addition to elevators). By developing support for healthy options throughout the community, families optimize their local resources and are better able to maintain healthy weight control habits.

Using the office environment and resources to promote obesity prevention

In effective lifestyle interventions, parents and children work with a behavioral specialist and attend regular treatment sessions, with options for phone sessions and email check-ins interspersed throughout the intervention. Families participate in group (45 minutes) and individual (30 minutes) sessions during each appointment; this format provides families with peer support through the group setting and a tailored intervention via the individual sessions. To optimize support in the home, additional family members are encouraged to attend as well.

Though these effective interventions have been established, recommended practices have not been implemented into routine practice. Thus, it is critical to extend beyond traditional settings and have providers work in concert with behavioral interventionists to provide integrated care and reinforce messaging across contexts. For instance, providers are in a prime position to identify at-risk families and make referrals for specialized weight loss intervention. Providers can then follow up with families once every three months to regularly track children’s health outcomes. Finally, providers can support the behavioral interventionists in establishing a unified treatment program for families by facilitating parents’ use of community resources and encouraging children’s development of positive social ties. Such collaborative effort is necessary to most effectively promote healthy behaviors, address families’ weight trajectories, and eliminate obesity.

Optimally, office policies and practices will ensure that staff members are equipped to confront weight-related problems. It is important for staff to be educated in behavior change principles so that they gain an understanding of how to help families to implement healthy strategies in their homes and communities. Office-based trainings can include the importance of early intervention, with instruction on how to appropriately and effectively intervene with parents and children and provide referrals.23 In addition, it is advantageous for staff to be educated in diversity awareness, as cultural differences may impact families’ values regarding weight status, body ideals, and parenting behaviors, and socioeconomic barriers (e.g., family finances and spending practices; access to community resources) may affect the intervention strategies that families are willing or able to implement. Ideally, providers will learn families’ stances on these issues to tailor their recommendations appropriately. Ongoing training and supervision in stigma awareness and reduction may be of benefit, as well.

Concerted efforts to 1) reduce providers’ skepticism regarding the efficacy of weight loss interventions; and 2) increase reimbursement for the provision of obesity-related services, will increase the likelihood that providers will engage families in weight loss interventions.23 Offering CME training opportunities, making accessible medical journals (e.g., Pediatrics), and increasing access to medically-relevant websites (e.g., AAP, CDC) are useful avenues for increasing providers’ knowledge of AAP recommendations.21

When addressing weight-related problems with families, it is imperative for staff to remain empathetic and utilize reflective listening. Ideally, staff will be trained to engage in open discussion with families about making healthy eating and activity changes, particularly as discomfort surrounding these conversations is a reported barrier for providers to address this issue.23 These conversations typically focus on understanding a family’s health behaviors, as well as their social network, with the goal of identifying sources of support for making healthy changes. Skills clinicians will teach to families include: how to engage in healthy eating; meal planning; and self-monitoring; and the tools for implementing these changes across the socioenvironmental contexts.

As mentioned above, the regularity of doctor’s appointments places PCPs in an ideal position to track and monitor children’s progress over time. Structuring appointments to allow time to calculate children’s BMI, review their weight trajectory, and discuss families’ progress in implementing healthy strategies will optimize intervention. Routine assessment of metabolic profiles and tracking risk for obesity-related health consequences is also imperative; this recommendation is line with the AAP guidelines for addressing pediatric obesity.5,19 It is crucial for staff to engage families about their weight goals and help families to problem-solve potential barriers. Discussing ways to maintain social support or seek avenues for developing healthy social ties is encouraged, as well. Overall, it is important that sessions focus on increasing families’ skills for at-home implementation of behavior change strategies.

Finally, it is recommended for obesity prevention that providers calculate BMI and address weight status with all families. Providers are encouraged to talk with parents of children who are normal weight to confirm whether they are currently engaging in healthy eating and activity behaviors; PCPs can promote the implementation or maintenance of these practices as needed and address any areas of concern to prevent the development of obesity. Noting family histories of overweight or obesity, obesity-related health problems, or gestational diabetes mellitus will help providers to screen for children at elevated risk for obesity. By using a universal approach, providers encourage healthy eating and activity practices and reduce risk for excessive weight gain among all families.

Promoting healthy lifestyles does not need to be limited to conversations between health professionals and patients; the office environment itself provides substantial opportunities to promote healthy lifestyle behaviors by making healthy resources and relevant prompts accessible and visible. First, offices can promote healthy lifestyle activities, such as emphasizing the use of stairs, increasing office walkability, and making breastfeeding rooms accessible. Second, healthy eating can be encouraged by removing vending machines, providing water fountains, and enforcing healthy standards for office meals (e.g., healthy staff lunches). Third, prompts for healthy local events and resources, such as farmers markets and community events for running, walking, or biking, can be made available in waiting rooms and hallways. It would be ideal for take-home materials with strategies for implementing behavior change to be made accessible. Finally, staff can set a positive example by modeling healthy behaviors (e.g., by not making unhealthy food visible, drinking water, walking during lunch breaks). In doing so, families receive consistent, healthful messaging that extends beyond the appointment session, in that the office environment models the infusion of healthy prompts across contexts.

Conclusions and future directions

The pressing pediatric obesity epidemic warrants immediate attention and a collective effort across health care professionals. This paper provides an overview of current PCP counseling practices, evidence-based recommendations for addressing pediatric obesity and eliciting behavior change, and encouragement to providers to implement these strategies in the primary care setting to help children lose weight and prevent excess weight gain.

By intervening early, providers are in a prime position to help families instill healthy habits. The earlier the intervention, the more potent providers can be: for instance, it is less likely that children become obese if parents never get into the habit of giving soda to their children.

Importantly, awareness of the discussed strategies represents only the first step. Implementing these changes with every family, at every visit, is critical for curbing the widespread problem of pediatric obesity. Researchers and clinicians must establish ongoing, open communication about the adoption of behavioral interventions and methods for training health professionals in these strategies. Future work is required to determine the optimal way to connect community resources to health care settings, including the use of social media and online forums for intervention. Building collaborative partnerships provides consistent health messaging and establishes greater referral services, thereby enhancing opportunities for families to embed healthy behaviors across all areas of their lives. Researching models and utilizing stakeholder (e.g., PCP) input on how best to disseminate this work lays necessary groundwork for widespread implementation. Through the employment of behavior change strategies into everyday clinical practice, providers will be in prime position to affect sustainable weight loss outcomes and promote healthier youth.

Provide within the manuscript a brief summary of important points and objectives for recall:

Family-based behavioral lifestyle interventions utilizing a socioenvironmental approach produce sustainable weight loss

Ideally, providers will be actively engaged in tracking children’s body mass index trajectory and addressing obesity with families

By employing the socioenvironmental approach, providers can ensure that children receive consistent health messaging and encourage families to implement healthy eating and activity behaviours across contexts

Footnotes

The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Denise E. Wilfley, Email: wilfleyd@psychiatry.wustl.edu, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 South Euclid Avenue, Campus Box 8134, St. Louis, Missouri 63110, Phone: 314-286-2079, Fax: 314-286-2091.

Andrea E. Kass, Email: kassa@psychiatry.wustl.edu, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 South Euclid Avenue, Campus Box 8134, St. Louis, Missouri 63110, Phone: 314-286-2113, Fax: 314-286-2091.

Rachel P. Kolko, Email: kolkor@psychiatry.wustl.edu, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 South Euclid Avenue, Campus Box 8134, St. Louis, Missouri 63110, Phone: 314-286-0253, Fax: 314-286-2091.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010 Jan 20;303(3):242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. Jama. 2006 Apr 5;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010 Jan 20;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000 Jun 8;(314):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barlow SE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007 Dec;120( Suppl 4):S164–192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.August GP, Caprio S, Fennoy I, et al. Prevention and treatment of pediatric obesity: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline based on expert opinion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Dec;93(12):4576–4599. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hampl SE, Carroll CA, Simon SD, Sharma V. Resource utilization and expenditures for overweight and obese children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007 Jan;161(1):11–14. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietz WH. Medical consequences of obesity in children and adolescents. In: Fairburn CG, Brownell KD, editors. Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 473–476. [Google Scholar]

- 9.BeLue R, Francis LA, Colaco B. Mental health problems and overweight in a nationally representative sample of adolescents: effects of race and ethnicity. Pediatrics. 2009 Feb;123(2):697–702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Mar;67(3):220–229. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss R, Dziura J, Burgert TS, et al. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2004 Jun 3;350(23):2362–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stovitz SD, Pereira MA, Vazquez G, Lytle LA, Himes JH. The interaction of childhood height and childhood BMI in the prediction of young adult BMI. Obesity. 2008;16(10):2336–2341. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nader PR, O’Brien M, Houts R, et al. Identifying risk for obesity in early childhood. Pediatrics. 2006 Sep;118(3):e594–601. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(13):869–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moss BG, Yeaton WH. Young children’s weight trajectories and associated risk factors: results from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort. Am J Health Promot. 2011 Jan-Feb;25(3):190–198. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090123-QUAN-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilfley DE, Vannucci A, White EK. Family-based behavioral interventions. In: Freemark M, editor. Pediatric Obesity: Etiology, Pathogenesis, and Treatment. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2010. pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldschmidt AB, Wilfley DE, Paluch RA, Roemmich JN, Epstein LH. Indicated prevention of adult obesity: Reference data for weight normalization in overweight children. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.416. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barton M. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2010 Feb;125(2):361–367. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krebs NF, Jacobson MS. Prevention of pediatric overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2003 Aug;112(2):424–430. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rhodes ET, Ebbeling CB, Meyers AF, et al. Pediatric obesity management: variation by specialty and awareness of guidelines. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2007 Jul;46(6):491–504. doi: 10.1177/0009922806298704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klein JD, Sesselberg TS, Johnson MS, et al. Adoption of body mass index guidelines for screening and counseling in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010 Feb;125(2):265–272. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young PC, DeBry S, Jackson WD, et al. Improving the prevention, early recognition, and treatment of pediatric obesity by primary care physicians. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2010 Oct;49(10):964–969. doi: 10.1177/0009922810370056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorsey KB, Mauldon M, Magraw R, Valka J, Yu S, Krumholz HM. Applying practice recommendations for the prevention and treatment of obesity in children and adolescents. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2010 Mar;49(2):137–145. doi: 10.1177/0009922809346567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holt N, Schetzina KE, Dalton WT, 3rd, Tudiver F, Fulton-Robinson H, Wu T. Primary care practice addressing child overweight and obesity: a survey of primary care physicians at four clinics in southern Appalachia. South Med J. 2011 Jan;104(1):14–19. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181fc968a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rausch JC, Perito ER, Hametz P. Obesity prevention, screening, and treatment: practices of pediatric providers since the 2007 expert committee recommendations. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2011 May;50(5):434–441. doi: 10.1177/0009922810394833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flower KB, Perrin EM, Viadro CI, Ammerman AS. Using body mass index to identify overweight children: barriers and facilitators in primary care. Ambul Pediatr. 2007 Jan-Feb;7(1):38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spivack JG, Swietlik M, Alessandrini E, Faith MS. Primary care providers’ knowledge, practices, and perceived barriers to the treatment and prevention of childhood obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010 Jul;18(7):1341–1347. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wake M, Baur LA, Gerner B, et al. Outcomes and costs of primary care surveillance and intervention for overweight or obese children: the LEAP 2 randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2009;339:b3308. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz RP, Hamre R, Dietz WH, et al. Office-based motivational interviewing to prevent childhood obesity: a feasibility study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007 May;161(5):495–501. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taveras EM, Gortmaker SL, Hohman KH, et al. Randomized controlled trial to improve primary care to prevent and manage childhood obesity: the high five for kids study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011 Aug;165(8):714–722. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCallum Z, Wake M, Gerner B, et al. Outcome data from the LEAP (Live, Eat and Play) trial: a randomized controlled trial of a primary care intervention for childhood overweight/mild obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007 Apr;31(4):630–636. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perrin EM, Finkle JP, Benjamin JT. Obesity prevention and the primary care pediatrician’s office. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007 Jun;19(3):354–361. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328151c3e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perrin EM, Jacobson Vann JC, Benjamin JT, Skinner AC, Wegner S, Ammerman AS. Use of a Pediatrician Toolkit to Address Parental Perception of Children’s Weight Status Nutrition and Activity Behaviors. Academic Pediatrics. 10(4):274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunnarsdottir T, Njardvik U, Olafsdottir AS, Craighead LW, Bjarnason R. The role of parental motivation in family-based treatment for childhood obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011 Aug;19(8):1654–1662. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braet C, Jeannin R, Mels S, Moens E, Van Winckel M. Ending prematurely a weight loss programme: the impact of child and family characteristics. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2010 Sep-Oct;17(5):406–417. doi: 10.1002/cpp.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West DS, Gorin AA, Subak LL, et al. A motivation-focused weight loss maintenance program is an effective alternative to a skill-based approach. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011 Feb;35(2):259–269. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang MW, Nitzke S, Guilford E, Adair CH, Hazard DL. Motivators and barriers to healthful eating and physical activity among low-income overweight and obese mothers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008 Jun;108(6):1023–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faith MS, Saelens BE, Wilfley DE, Allison DB. Behavioral treatment of childhood and adolescent obesity: Current status, challenges, and future directions. In: Thompson JK, Smolak L, editors. Body Image, Eating Disorders, and Obesity in Youth: Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 313–339. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilfley DE, Tibbs TL, Van Buren DJ, Reach KP, Walker MS, Epstein LH. Lifestyle interventions in the treatment of chilldhood overweight: A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. Health Psychol. 2007;26(5):521– 532. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.5.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Epstein LH. Family-based behavioral intervention for obese children. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20:14– 21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Epstein LH, Myers MD, Raynor HA, Saelens BE. Treatment of pediatric obesity. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3):S554– 570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epstein LH, Paluch R, Roemmich JN, Beecher MD. Family-based obesity treatment: Then and now. Twenty-five years of pediatric obesity treatment. Health Psychol. 2007;26(4):381– 391. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Epstein LH, Valoski AM, Koeske R, Wing RR. Family-based behavioral weight control in obese young children. J Am Diet Assoc. 1986;86:481– 484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Epstein LH, Valoski AM, Wing RR, McCurley J. Ten-year follow-up of behavioral, family-based treatment for obese children. JAMA. 1990;264:2519– 2523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Epstein LH, Valoski AM, Wing RR, McCurley J. Ten-year outcomes of behavioral family based treatment for childhood obesity. Health Psychol. 1994;13:373– 383. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.5.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Epstein LH, Wing RR, Woodall K, Penner BC, Kress MJ, Koeske R. Effects of family-based behavioral treatment on obese 5–8 year old children. Behav Ther. 1985;16:205– 212. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalarchian MA, Levine MD, Arslanian SA, et al. Family-based treatment of severe pediatric obesity: randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2009 Oct;124(4):1060–1068. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pratt CA, Stevens J, Daniels S. Childhood obesity prevention and treatment: Recommendations for future research. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(3):249–252. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Epstein LH, Valoski A, Wing RR, McCurley J. Ten-Year Follow-up of Behavioral, Family-Based Treatment for Obese Children. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990 Nov 21;264(19):2519–2523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.ADA. Position of the American Dietetic Association: individual-, family-, school-, and community-based interventions for pediatric overweight. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006 Jun;106(6):925–945. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanofsky-Kraff MH, Hayden-Wade HA, Cavazos P, Wilfley DE. Pediatric overweight treatment and prevention. In: Anderson R, editor. Overweight: Etiology, Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention. Champaign, IL: Kuman Kinetics; 2003. pp. 155–176. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hunt MS, Katzmarzyk PT, Perusse L, Rice T, Rao DC, Bouchard C. Familial resemblance of 7-year changes in body mass and adiposity. Obes Res. 2002;10:507– 517. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Golan M, Weizman A. Familial approach to the treatment of childhood obesity: Conceptual model. J Nutr Educ. 2001;33(2):102– 107. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Young KM, Northern JJ, Lister KM, Drummond JA, O’Brien WH. A meta-analysis of family-behavioral weight-loss treatments for children. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:240– 249. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davison KK, Birch LL. Childhood overweight: A contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obes Rev. 2001;(2):159–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kitzmann KM, Beech BM. Family-based interventions for pediatric obesity: Methodological and conceptual challenges from family psychology. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20(2):175– 189. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goldschmidt AB, Stein RI, Saelens BE, Theim KR, Epstein LH, Wilfley DE. Importance of early weight change in a pediatric weight management trial. Pediatrics. 2011 Jul;128(1):e33–39. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wrotniak BH, Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Roemmich JN. Parent weight change as a predictor of child weight change in family-based behavioral obesity treatment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004 Apr;158(4):342–347. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McGovern L, Johnson JN, Paulo R, et al. Clinical review: treatment of pediatric obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Dec;93(12):4600–4605. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Golan M, Fainaru M, Weizman A. Role of behaviour modification in the treatment of childhood obesity with the parents as the exclusive agents of change. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998 Dec;22(12):1217–1224. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Epstein LH, Wisniewski L, Weng R. Child and parent psychological problems influence child weight control. Obes Res. 1994 Nov;2(6):509–515. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilfley DE, Stein RI, Saelens BE, et al. Efficacy of maintenance treatment approaches for childhood overweight: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2007 Oct 10;298(14):1661–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DeWall CN, Bushman BJ. Social acceptance and rejection: The sweet and the bitter. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2011;20(4):256–260. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jefferson A. Breaking down barriers-examining health promoting behaviour in the family. Kellogg’s Family Health Study 2005. Nutrition Bulletin. 2006;31:60–64. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zeller MH, Reiter-Purtill J, Ramey C. Negative peer perceptions of obese children in the classroom environment. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008 Apr;16(4):755–762. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wolch J, Jerrett M, Reynolds K, et al. Childhood obesity and proximity to urban parks and recreational resources: A longitudinal cohort study. Health Place. 2010 Oct 15; doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oreskovic NM, Winickoff JP, Kuhlthau KA, Romm D, Perrin JM. Obesity and the built environment among Massachusetts children. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2009 Nov;48(9):904–912. doi: 10.1177/0009922809336073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Epstein LH, Raja S, Oluyomi T, et al. Activity and eating built environments influence child weight loss over two years. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wardle J, Carnell S. Appetite is a Heritable Phenotype Associated with Adiposity. Ann Behav Med. 2009 Sep 3; doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carnell S, Wardle J. Appetitive traits and child obesity: measurement, origins and implications for intervention. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008 Nov;67(4):343–355. doi: 10.1017/S0029665108008641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carnell S, Wardle J. Appetitive traits in children. New evidence for associations with weight and a common, obesity-associated genetic variant. Appetite. 2009 Oct;53(2):260–263. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Temple JL, Legierski CM, Giacomelli AM, Salvy SJ, Epstein LH. Overweight children find food more reinforcing and consume more energy than do nonoverweight children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 May;87(5):1121–1127. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Marmarosh C, Morgan CM, Yanovski JA. Eating-disordered behaviors, body fat, and psychopathology in overweight and normal-weight children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004 Feb;72(1):53–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goldschmidt AB, Aspen VP, Sinton MM, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley DE. Disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in overweight youth. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008 Feb;16(2):257–264. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nederkoorn C, Braet C, Van Eijs Y, Tanghe A, Jansen A. Why obese children cannot resist food: the role of impulsivity. Eat Behav. 2006 Nov;7(4):315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Han JC, Anandalingam K, et al. The FTO gene rs9939609 obesity-risk allele and loss of control over eating. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Dec;90(6):1483–1488. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wardle J, Llewellyn C, Sanderson S, Plomin R. The FTO gene and measured food intake in children. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009 Jan;33(1):42–45. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Birch LL, Fisher JO. Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998 Mar;101(3 Pt 2):539–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jansen A, Theunissen N, Slechten K, et al. Overweight children overeat after exposure to food cues. Eat Behav. 2003 Aug;4(2):197–209. doi: 10.1016/S1471-0153(03)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mirch MC, McDuffie JR, Yanovski SZ, et al. Effects of binge eating on satiation, satiety, and energy intake of overweight children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 Oct;84(4):732–738. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tanofsky-Kraff M, McDuffie JR, Yanovski SZ, et al. Laboratory assessment of the food intake of children and adolescents with loss of control eating. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Mar;89(3):738–745. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Butte NF, Cai G, Cole SA, et al. Metabolic and behavioral predictors of weight gain in Hispanic children: the Viva la Familia Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007 Jun;85(6):1478–1485. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.6.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hill C, Saxton J, Webber L, Blundell J, Wardle J. The relative reinforcing value of food predicts weight gain in a longitudinal study of 7--10-y-old children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Aug;90(2):276–281. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Seeyave DM, Coleman S, Appugliese D, et al. Ability to delay gratification at age 4 years and risk of overweight at age 11 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009 Apr;163(4):303–308. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Schvey NA, Olsen CH, Gustafson J, Yanovski JA. A prospective study of loss of control eating for body weight gain in children at high risk for adult obesity. Int J Eat Disord. 2009 Jan;42(1):26–30. doi: 10.1002/eat.20580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Glass TA, McAtee MJ. Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: extending horizons, envisioning the future. Soc Sci Med. 2006 Apr;62(7):1650–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Huang TT, Drewnosksi A, Kumanyika S, Glass TA. A systems-oriented multilevel framework for addressing obesity in the 21st century. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009 Jul;6(3):A82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E, Stettler N, et al. Population-based prevention of obesity: the need for comprehensive promotion of healthful eating, physical activity, and energy balance: a scientific statement from American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Interdisciplinary Committee for Prevention (formerly the expert panel on population and prevention science) Circulation. 2008 Jul 22;118(4):428–464. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bouton ME. Context, ambiguity, and unlearning: sources of relapse after behavioral extinction. Biol Psychiatry. 2002 Nov 15;52(10):976–986. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01546-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, et al. Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Feb;81(2):341–354. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.81.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Epstein LH, Myers MD, Raynor HA, Saelens BE. Treatment of pediatric obesity. Pediatrics. 1998 Mar;101(3 Pt 2):554–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wilfley DE, Van Buren DJ, Theim KR, et al. The use of biosimulation in the design of a novel multilevel weight loss maintenance program for overweight children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010 Feb;18( Suppl 1):S91–98. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jeffery RW, Drewnowski A, Epstein LH, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: current status. Health Psychol. 2000 Jan;19(1 Suppl):5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Byrne KJ. Efficacy of lifestyle modification for long-term weight control. Obes Res. 2004 Dec;12( Suppl):151S–162S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dietz W, Lee J, Wechsler H, Malepati S, Sherry B. Health plans’ role in preventing overweight in children and adolescents. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007 Mar-Apr;26(2):430–440. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tsiros MD, Sinn N, Coates AM, Howe PR, Buckley JD. Treatment of adolescent overweight and obesity. Eur J Pediatr. 2008 Jan;167(1):9–16. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0575-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Goldfield A, Chrisler JC. Body stereotyping and stigmatization of obese persons by first graders. Percept Mot Skills. 1995 Dec;81(3 Pt 1):909–910. doi: 10.2466/pms.1995.81.3.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gortmaker SL, Must A, Perrin JM, Sobol AM, Dietz WH. Social and economic consequences of overweight in adolescence and young adulthood. N Engl J Med. 1993 Sep 30;329(14):1008–1012. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hayden-Wade HA, Stein RI, Ghaderi A, Saelens BE, Zabinski MF, Wilfley DE. Prevalence, characteristics, and correlates of teasing experiences among overweight children vs. non-overweight peers. Obes Res. 2005 Aug;13(8):1381–1392. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Striegel-Moore RH, Schreiber GB, Lo A, Crawford P, Obarzanek E, Rodin J. Eating disorder symptoms in a cohort of 11 to 16-year-old black and white girls: the NHLBI growth and health study. Int J Eat Disord. 2000 Jan;27(1):49–66. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200001)27:1<49::aid-eat6>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dietz WH, Robinson TN. Clinical practice. Overweight children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2005 May 19;352(20):2100–2109. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp043052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Salvy SJ, Coelho JS, Kieffer E, Epstein LH. Effects of social contexts on overweight and normal-weight children’s food intake. Physiol Behav. 2007 Dec 5;92(5):840–846. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Salvy SJ, Kieffer E, Epstein LH. Effects of social context on overweight and normal-weight children’s food selection. Eat Behav. 2008 Apr;9(2):190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Salvy SJ, Romero N, Paluch R, Epstein LH. Peer influence on pre-adolescent girls’ snack intake: effects of weight status. Appetite. 2007 Jul;49(1):177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Romero ND, Epstein LH, Salvy SJ. Peer modeling influences girls’ snack intake. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009 Jan;109(1):133–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]