Abstract

Woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV), which is closely related to human hepatitis B virus and is considered to be principally hepatotropic, invades the host's lymphatic system and persists in lymphoid cells independently of whether the infection is symptomatic and serologically evident or concealed. In this study, we show, with the woodchuck model of hepatitis B, that hepadnavirus can establish an infection that engages the lymphatic system, but not the liver, and persists in the absence of virus serological markers, including antiviral antibodies. This primary occult infection is caused by wild-type virus invading the host at a quantity usually not greater than 103 virions. It is characterized by trace virus replication progressing in lymphatic organs and peripheral lymphoid cells that, with time, may also spread to the liver. The infection is transmissible to virus-naive hosts as an asymptomatic, indefinitely long, occult carriage of small amounts of biologically competent virus. In contrast to residual silent WHV persistence, which normally endures after the resolution of viral hepatitis and involves the liver, primary occult infection restricted to the lymphatic system does not protect against reinfection with a large, liver-pathogenic WHV dose; however, the occult infection is associated with a swift recovery from hepatitis caused by the superinfection. Our study documents that the lymphatic system is the primary target of WHV infection when small quantities of virions invade a susceptible host.

Replication and retention of virus in cells of the immune system characterize many persistent viral infections and are a major hindrance to sterilizing antiviral therapy. Human hepatitis B virus (HBV) and its close relative woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV), infecting the eastern American woodchuck (Marmota monax), are noncytopathic hepadnaviruses which cause similar courses and outcomes of liver disease (7, 27, 29, 41, 42). It is estimated that 350 to 400 million people worldwide are chronically infected with HBV (43). This lifelong infection, with which the patient is serologically HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) reactive, is accompanied by chronic hepatitis that frequently advances to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). It is now evident that HBV also elicits occult long-term persistence, as has been determined from the detection of the virus by HBV DNA PCR but not by the current and otherwise sensitive immunoassays for HBsAg (1-3, 7, 10, 22, 25, 34, 36, 38, 45, 46). The epidemiological and pathogenic importance of this silent HBV carriage is increasingly evident, particularly in regard to (i) the transmission of virus traces through seemingly HBV-negative blood transfusion, hemodialysis, or organ transplantation (5, 12, 37); (ii) cytotoxic or immunosuppressive therapy (13, 24); and (iii) the pathogenesis of liver diseases considered to be cryptogenic, e.g., HCC (4, 6, 21, 44). In the woodchuck model of hepatitis B, which is the closest natural animal model for the study of HBV pathobiology (27, 29, 41, 42), the lifelong silent persistence of WHV is an invariable consequence of resolved viral hepatitis (11, 28, 33). This residual infection is accompanied by the development of HCC in about 20% of the animals that recover (17, 33).

An analysis of HBV genome expression years after recovery from an episode of acute hepatitis showed that virus traces persist in serum, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), and the liver, despite circulating antibodies to HBsAg (anti-HBs) and a vigorous, HBV-specific cytotoxic-T-cell response (3, 7, 34, 36, 38, 45, 46). HBV DNA, its replicative intermediates (including covalently closed circular DNA [cccDNA]), and viral RNA transcripts have been detected in PBMC from patients with chronic hepatitis B (18, 26, 40). In the woodchuck model, WHV normally invades the host's lymphatic system and lymphoid cells (i.e., lymphomononuclear cells constituting PBMC and lymphatic organs, which are mainly of lymphoid and, for a minority of cells, myeloid origin). Lymphoid cells are a reservoir of replicating virus independently of whether the primary infection is serologically evident or occult (9, 16, 28, 31, 33, 35). It has also been shown that WHV produced by lymphoid cells can establish productive infection in cultured hepatocytes and lymphoid cells and can establish viral hepatitis and HCC in susceptible animals (20, 33). Hence, the accumulated data indicate that although hepatocytes are the site of the most vigorous replication of HBV and WHV in serologically diagnosed infections, both viruses are also lymphotropic and can propagate in the lymphatic system.

Recent findings with the woodchuck model of hepatitis B revealed yet another form of occult hepadnavirus persistence. Under certain natural or experimental conditions, i.e., in offspring born to dams recovered from WHV hepatitis (9), in adult animals inoculated with viable lymphoid cells obtained long after the resolution of acute WHV hepatitis (33), or with very small WHV doses (20), hepadnavirus can elicit a primary, serologically silent infection confined to the lymphatic system. This infection is characterized by trace quantities of circulating virus and by scanty virus replication in lymphoid tissue but not in the liver (9, 20, 33, 35). The nature of the viral prerequisite leading to the establishment of this extrahepatic form of occult hepadnavirus persistence was unknown. Michalak hypothesized that a dose of invading virus and/or the existence of a lymphotropic virus variant might be the underlying reason (28). To test these possibilities and to delineate the features of this newly identified form of hepadnaviral carriage, we have applied two complementary investigative approaches. The first aimed at the elucidation of whether occult, naturally acquired neonatal infection limited to the lymphatic system is transmissible to virus-naive, immunocompetent hosts and, if so, whether this infection retains its molecular and immunovirological properties through the passage. The second aimed at the generation of a reproducible model of occult, lymphatic-system-restricted infection by using a wild-type, serum-derived virus and by testing how this infection affects the host's susceptibility to and recovery after challenge with a massive virus dose normally causing hepatitis. Our findings imply that the lymphatic-system-restricted primary occult infection (POI) is caused by wild-type virus and that the quantity of invading virions predetermines whether the infection is silent and confined to the lymphatic system or serologically evident and liver pathogenic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Infection experiments were carried out with 2- to 3-year-old healthy woodchucks housed in the Woodchuck Hepatitis Research Facility at Memorial University, St. John's, Canada. The possibility of prior exposure to WHV was excluded based on negative serological results for WHV infection markers and the absence of WHV DNA as determined by nested-PCR-Southern hybridization assay (sensitivity, ≤10 virus genome equivalents [vge]/ml) with randomly selected serum, PBMC, and liver biopsy samples, as described previously (33).

Inocula from occult lymphatic-system-restricted WHV infection.

Woodchuck 3B/M, born to dam B, which resolved acute WHV hepatitis and was positive for antibodies to WHV surface antigen (anti-WHs), carried WHV DNA in serum and the lymphatic tissues but not in the liver during a 15-month follow-up after birth (9). WHV derived from the serum of offspring 3B/M was intravenously (i.v.) injected at a dose of ∼104 vge into adult 260/M. Woodchuck 260/M acquired POI accompanied by serum WHV DNA levels not exceeding 102 vge/ml, as reported previously (9). For the present study, inocula were prepared from the plasma of 3B/M and from plasma and splenocytes of 260/M (Fig. 1A). Thus, plasma samples collected at autopsy from 3B/M (20 ml) and 260/M (10 ml) were ultracentrifuged at 200,000 × g for 18 h in a SW 50.1 rotor (Beckman Instruments Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.). The resulting concentrates, containing ∼1 × 103 and ∼5 × 102 WHV vge, were i.v. injected into two WHV-naive woodchucks, 2115/M and 2117/M, respectively. Sera and PBMC were collected weekly until week 10 postinfection (p.i.) and then biweekly afterwards. Liver biopsy specimens were obtained before infection and at weeks 6 and 22 p.i. At week 23 p.i., both woodchucks were challenged with WHV/tm3 inoculum at doses of 1.1 × 1010 DNase-protected WHV vge (see below). Liver samples were collected at weeks 6, 29, and 46 thereafter. In a related experiment, splenocytes isolated from woodchuck 260/M, which were treated with DNase and trypsin to eliminate the possible carryover of cell surface-associated WHV virions and DNA (33), were i.v. injected at a concentration of 6.2 × 106 cells (80% viability) into 2120/M. The animal was euthanized at week 18 p.i. (Fig. 1).

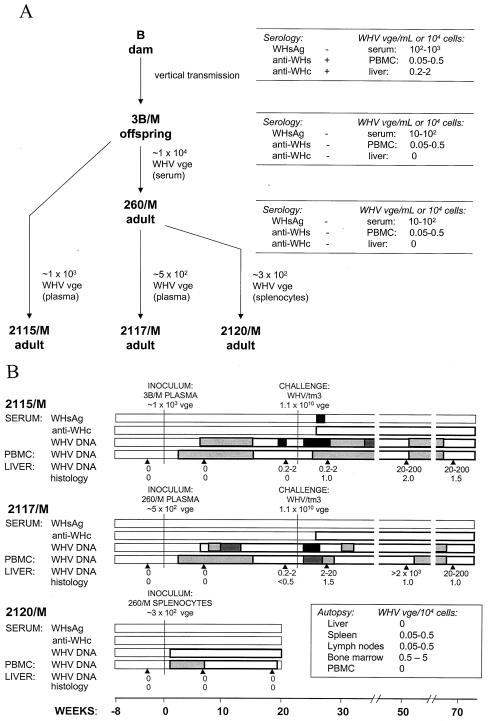

FIG. 1.

Serial passage of occult WHV infection restricted to the lymphatic system in virus-susceptible woodchucks. (A) Outline of the experiment showing animals and features of WHV infection at the time of acquisition of virus inocula. (B) Serological and WHV genome expression profiles and results of liver histology after inoculation of virus-naive adult woodchucks with WHV derived from animal 3B/M with neonatally acquired POI confined to the lymphatic system and from woodchuck 260/M with the same type of infection gained after injection with 3B/M serum. Animals 2117/M and 2115/M were subsequently challenged with the WHV/tm3 inoculum containing a wild-type WHV at a dose of 1.1 × 1010 DNase-protected virions. The graphs display the times of the primary inoculation (week 0) and the challenge with WHV (week 23), the appearance and the duration of serum WHsAg (▪) and anti-WHc (□), and the expression of WHV DNA in serum, PBMC, and liver biopsy samples. Anti-WHs was not detected (data not shown). WHV DNA in serum, PBMC, and liver samples was detected by direct or nested PCR, followed by Southern blot identification of the amplified sequences. The serum WHV DNA content did not exceed 10 vge/ml during follow-up and is represented by white bars. The levels of WHV genomes in PBMC are shown as follows: white bars, 0.005 to 0.5 vge/104 cells; light-grey bars, 0.5 to 5 vge/104 cells; dark-grey bars, 5 to 50 vge/104 cells; and black bars, >50 vge/104 cells. The quantities of WHV genomes in liver samples obtained at the time points marked by arrowheads were assessed as described above and are expressed as estimated numbers of WHV vge per 104 cells, as reported previously (33). Liver alterations are presented as the histological degree of hepatitis ranging from 0 to 3, assessed according to the criteria described previously (11, 32).

Wild-type WHV inoculum.

WHV/tm3 inoculum was prepared from a pool of sera from a single chronic WHV carrier. This inoculum has proven to be highly liver pathogenic and at 1.1 × 1010 vge/dose induced hepatitis in ∼85% of adult woodchucks, as determined by the presence of WHsAg in their sera (28, 33). The inoculum contained a wild-type WHV DNA sequence identical with that in the liver and spleen of the donor, as revealed by sequencing of the cloned complete WHV genomes. To determine whether a wild-type virus can establish POI, nine WHV-naive animals were i.v. injected with increasing doses of WHV/tm3 ranging from ∼10 to 107 DNase-protected virions (33). Thus, woodchucks 1/F, 2/F, and 3/F were inoculated with ∼10 vge, 4/M and 5/F were inoculated with 103 vge, 6/M and 7/F were inoculated with 105 vge, 8/F was inoculated with 106 vge, and 9/F was inoculated with 107 vge (see Fig. 4). The animals were bled weekly until week 6 p.i. and then biweekly afterwards. Liver biopsies were performed before inoculation and at weeks 5 and 12 p.i. At week 18 p.i., each animal, except 1/F and 8/F, was challenged with 1.1 × 1010 vge of WHV/tm3 inoculum. Sera and PBMC were collected up to month 12, and liver samples were collected at weeks 6, 36, and 48 after challenge. 1/F was euthanized at week 18 p.i. to assess WHV expression in lymphoid organs. Woodchuck 8/F developed chronic hepatitis and was monitored until HCC was diagnosed at month 25 p.i.

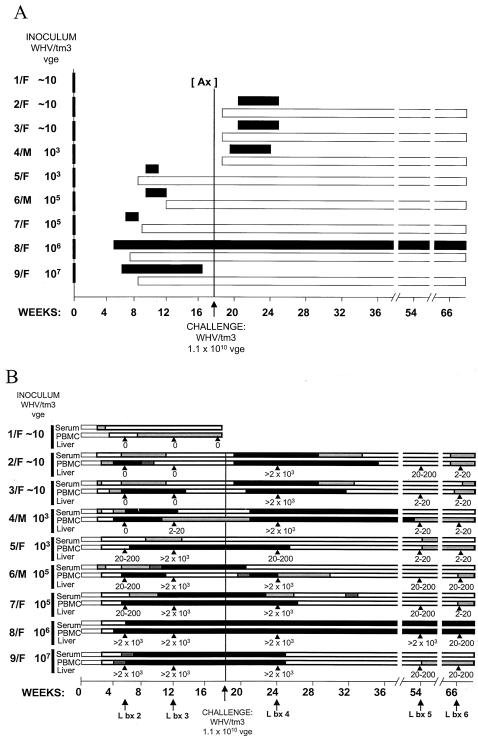

FIG. 4.

Serological and molecular profiles of WHV infection in woodchucks injected with increasing doses of a wild-type WHV and then challenged with a massive dose of the same inoculum. Healthy, initially WHV-naive woodchucks were injected (week 0) with the indicated amounts (vge) of the serum-derived WHV/tm3 inoculum. At week 18 p.i., the animals (except 1/F) were challenged with the same WHV/tm3 inoculum at a dose of 1.1 × 1010 vge, known to normally induce acute hepatitis in naive animals. (A) Detection of WHsAg in serum (▪) and anti-WHc (□). Anti-WHs was transiently identified in 5/F, 6/M, and 7/F after the clearance of WHsAg from serum following primary WHV inoculation and in 2/F, 3/F, and 4/M after challenge with a dose of 1.1 × 1010 vge (data not shown). (B) Detection of WHV DNA in sequential serum, PBMC, and liver samples. Estimated WHV vge levels detected in serum are depicted as follows: white bars, 1 to 10 vge/ml; light-grey bars, 10 to 102 vge/ml; dark-grey bars, 102 to 103 vge/ml; and black bars, >103 vge/ml. WHV DNA quantities identified in PBMC are shown as follows: white bars, 0.005 to 0.5 vge/104 cells; light-grey bars, 0.5 to 5 vge/104 cells; dark-grey bars, 5 to 50 vge/104 cells; and black bars, >50 vge/104 cells. Likewise, the levels of WHV DNA detected in liver biopsy or autopsy samples at the time points indicated by arrowheads were shown as the estimated number of WHV vge per 104 cells.

Sample collection and cell preparation.

PBMC were harvested from sodium-EDTA-treated blood on Ficoll-Paque Plus (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) (20). Liver biopsy samples were obtained by surgical laparotomy (33). At autopsy, serum, PBMC, liver, spleen, bone marrow, lymph nodes, and other organs were collected. For histological examinations, tissue fragments were processed to paraffin. Liver sections were stained and hepatic lesions were assessed as described previously (11, 30, 32). Liver tissue fragments obtained during biopsy or autopsy were washed in a few changes of Hanks' balanced salt solution prior to DNA extraction to remove residual blood. In selected cases, splenocytes were isolated at autopsy (20). In some instances, PBMC and splenocytes were cultured with phytohemagglutinin (5 μg/ml) for 72 h to enhance the expression of WHV DNA and cccDNA (9, 33). DNase-trypsin-DNase treatment preceded DNA extraction to eliminate the potential carryover of virions and virus DNA fragments on the cell surface (20, 35).

Serological and WHV DNA dot blot assays.

WHsAg, anti-WHs, and antibodies to WHV core antigen (anti-WHc) were assayed as described elsewhere (33). The serum WHV DNA was evaluated by dot blot hybridization using 32P-labeled complete cloned (recombinant) WHV DNA (rWHV DNA) (9, 20). Hybridization signals were quantified by phosphorimage densitometry with twofold serial dilutions of rWHV DNA as the reference (sensitivity, 2 × 106 vge/ml) (20). When negative, WHV DNA was assayed by PCR-Southern blotting.

DNA extraction and PCR for WHV DNA and cccDNA.

DNA from 50 μl of serum or 1 μg of DNA (unless otherwise indicated) from PBMC, splenocytes, liver, or lymphoid tissue (i.e., spleen, bone marrow, and lymph node), isolated by the proteinase K-phenol-chloroform method (9, 34), was amplified by PCR by using primers and conditions reported previously (33). Three sets of direct and nested oligonucleotide primer pairs specific for nonoverlapping regions of WHV core (C), envelope (S), and X genes were used to test each sample (9, 33).

For PCR detecting WHV cccDNA (i.e., double-stranded, uninterrupted WHV DNA), enzymatic treatment, primers, and conditions previously established in this laboratory were applied (20). Briefly, 2 to 5 μg of DNA was digested with mung bean nuclease (40 U; Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) in the presence of 1 mM zinc acetate (pH 5.0) for 30 min at 37°C to eliminate single-stranded DNA sequences. The digestion was terminated with 0.1 M EDTA. The nuclease-treated DNA (1 to 2.5 μg) was amplified with PGAP1 and MCOR primers in a 100-μl volume of PCR cocktail containing 3 mM MgCl2 to overcome the inhibitory effect of EDTA. If required, 10 μl of the direct-PCR product was amplified by nested PCR with primers XINT and CCCV, as described previously (20).

All DNA extractions were performed in parallel with mock samples containing Tris-EDTA buffer (1 mM EDTA in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) instead of DNA. In addition, DNA samples from the sera, PBMC, and livers of healthy WHV-naive animals and chronically infected animals with WHsAg-reactive sera were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. The same DNA samples treated with mung bean nuclease were utilized as negative or positive controls in reactions detecting WHV cccDNA. In addition, complete double-stranded rWHV DNA was used as a positive control in PCRs assessing the presence of individual WHV gene sequences or cccDNA. For the final PCR contamination controls, water was added instead of template DNA or the direct-PCR product to the direct- or nested-PCR cocktail, respectively. Southern blot analysis of the PCR products was routinely carried out to verify the specificity of the virus sequence detection and the validity of the controls. The sensitivity of the combined nested-PCR and Southern blot hybridization assays was ≤10 vge/ml, and that of the assay for WHV cccDNA was ∼102 vge/ml (20).

Real-time PCR for WHV DNA quantification.

In selected cases, WHV DNA was quantified by real-time PCR by using the a LightCycler (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), WHV C gene-specific primers, and detection of the amplified products through fluorescence resonance energy transfer. For this purpose, primers WHCF (5′-CTTTCCTGATCTTAATGCT; positions 2089 to 2107) and WHCR (5′-AGTCGAGAGAATGGGTG; 2430 to 2446) and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated probe WHC1 (WHC1-FITC; 5′-TGGACACTGCTACTGCCTTG; 2112 to 2131) and LC 640 Red-conjugated probe WHC2 (WHC2-RED; 5′-TGAAGAAAAGCTAACAGGTAGGAAC; 2133 to 2160) were used. The numbers following the sequences denote the nucleotide positions of the primer or probe sequences in the WHV genome (GenBank accession no. M11082) (15). Primers and probes were added at concentrations of 0.5 and 0.2 μM, respectively, to each reaction mixture containing 4 mM MgCl2 and the FastStart DNA master hybridization probe kit mix (Roche Diagnostics). Reactions were carried out with the following parameters: initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 55 cycles, each performed for 10 s at 95°C, 10 s at 49°C, and 13 s at 72°C. The melting of the products was done at 95°C with 0.2°C/s increments. Specific WHV amplicons melted at 58.1°C. Negative and positive controls were routinely included, as described above for the standard PCR assays. In addition, 10-fold serial dilutions of complete rWHV DNA were included for the enumeration of viral loads in test samples. The sensitivity of the real-time PCR assay was 102 vge/ml. Parallel analyses of the same serum and PBMC samples from animals with occult WHV infection by the real-time PCR and nested PCR-Southern blot hybridization consistently showed that, although real-time PCR allowed, as expected, for more direct and exact quantification of WHV DNA loads, its sensitivity was at least 10-fold lower than that of the nested-PCR-nucleic acid hybridization assay routinely used throughout this study.

WHV DNA sequencing.

DNA from selected serum, lymphoid cell, and tissue samples was subjected to PCR with back-to-back primers amplifying the complete WHV genome, as reported previously (33). When required, fragments of the full-length WHV DNA were further amplified with WHV gene-specific primers (9). The PCR products were either cloned by using the TA cloning system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) and automatically sequenced or sequenced by using the Fmol DNA sequencing system (Promega, Madison, Wis.), as described previously (9).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences for the cloned complete WHV genomes were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers AY334075 (for WHV/tm3 inoculum), AY334076 (for liver-derived WHV), and AY334077 (for spleen-derived WHV).

RESULTS

Transmission of primary occult WHV infection.

To determine the infectivity and pathogenic competence of WHV in POI, inocula derived from woodchuck 3B/M (which was born to a mother convalescent from WHV hepatitis and had serologically undetectable infection with small amounts of WHV DNA in its serum, PBMC, and lymphatic organs but not in its liver [9]) were i.v. injected into virus-naive adults 260/M and 2115/M (Fig. 1A). Subsequently, plasma and splenocytes from 260/M, which developed POI (9), were i.v. administered to 2117/M and 2120/M, respectively (Fig. 1A). Animals 2115/M, 2117/M, and 2120/M, similarly to 3B/M and 260/M (9), developed infection negative for WHsAg, anti-WHc, anti-WHs, and WHV DNA by dot blot hybridization (sensitivity, 2 × 106 vge/ml). Nevertheless, WHV DNA was detected by nested-PCR-Southern blotting assay (sensitivity, ≤10 vge/ml) (Fig. 1B) in the sera and PBMC of all the animals from day 7 or 14 p.i.

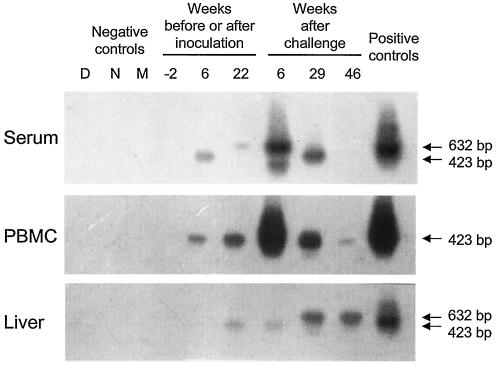

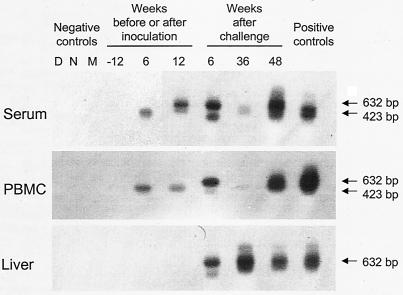

Liver biopsy samples gathered before and at week 6 p.i. from woodchuck 2115/M (injected with ∼5 × 102 WHV vge derived from 3B/M plasma) and woodchuck 2117/M (injected with ∼1 × 103 vge obtained from 260/M plasma) were entirely nonreactive for WHV DNA, even when 5 μg of total liver DNA was used for direct PCR, and had normal histologies (Fig. 1B and 2). However, liver tissue obtained 4 months later displayed WHV DNA at 0.2 to 2 vge/104 cells in both animals (Fig. 1B and 2). These virus signals occurred in the absence of liver alterations in 2115/M, while minimal lymphomononuclear cell infiltrations and a moderate proliferation of bile ducts were seen in woodchuck 2117/M.

FIG. 2.

WHV DNA expression in serum, in circulating lymphoid cells, and in liver biopsy samples collected from woodchuck 2117/M, which was inoculated with WHV derived from an animal with neonatally acquired, lymphatic-system-restricted POI that was then challenged with a massive, liver-pathogenic dose of WHV. Total DNA isolated from liver biopsy samples and from parallel PBMC and serum samples obtained prior to inoculation (week −2; negative controls), after inoculation with ∼5 × 102 WHV vge from 3B/M plasma (weeks 6 and 22 p.i.), and after challenge at week 23 p.i. with the WHV/tm3 inoculum at a dose of 1.1 × 1010 WHV vge (weeks 6, 29, and 46 after challenge) was tested for WHV DNA by direct and, if negative, by nested PCR with WHV S gene-specific primers. The amplicons were detected by Southern blot hybridization to rWHV DNA. For contamination controls, water was added instead of DNA and the sample was amplified by a direct (lane D) or nested (lane N) reaction and mock treated (lane M) as test DNA. The positive controls consisted of DNA isolated from the serum, PBMC, or liver of a woodchuck with chronic WHV infection that was positive for WHsAg in serum. Positive signals showed the expected 632-bp (direct-PCR) or 423-bp (nested-PCR) nucleotide fragments.

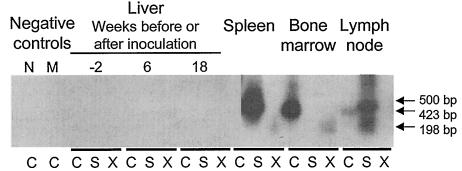

Liver samples obtained prior to and at weeks 6 and 18 p.i. from animal 2120/M, injected with ∼3 × 102 vge contained within splenocytes of 260/M (Fig. 1A), had normal histologies and were virus DNA nonreactive (Fig. 3). Despite this fact, autopsy tissues collected at week 18 p.i. unveiled WHV infection confined to the lymphatic system (Fig. 1A), as was observed in woodchucks 3B/M and 260/M (9). Thus, only the spleen, lymph nodes, and bone marrow of 2120/M were WHV DNA reactive at ∼5 vge/104 cells (Fig. 1B and 3), while PBMC carried WHV at ∼0.05 to 0.5 vge/104 cells between weeks 3 and 16 p.i. (Fig. 1B). Comparable results were obtained by real-time PCR. WHV cccDNA was detected in the spleen and bone marrow of 2120/M (data not shown). WHV pre-S, S, C, and X gene sequences from 2120/M spleen and bone marrow did not show alterations compared with the wild-type WHV present in 3B/M's spleen and in two liver biopsy samples obtained from its mother (dam B) before and after parturition (9).

FIG. 3.

Analysis of WHV DNA expression in liver and lymphoid tissues collected from woodchuck 2120/M, inoculated with splenocytes isolated from animal 260/M, which had acquired POI after injection with the serum of offspring 3B/M. Five-microgram samples of total DNA from liver biopsy specimens collected before (week −2; negative control) and after (weeks 6 and 18 p.i.) inoculation with splenocytes carrying an estimated 3 × 102 WHV vge and 1 μg of DNA from the spleen, bone marrow, or lymph nodes collected at autopsy (week 18 p.i.) were tested for WHV DNA by nested PCR with C, S, and X gene-specific primers and by Southern blot analysis of the products derived. Contamination controls included samples injected with water added instead of DNA (lane N) and a mock sample (lane M) that had been extracted and treated under conditions identical to those for DNA test samples. Positive samples showed the expected molecular sizes of the amplified virus C (500-bp), S (423-bp), and X (192-bp) gene fragments.

Low doses of wild-type WHV cause occult lymphatic-system-restricted infection.

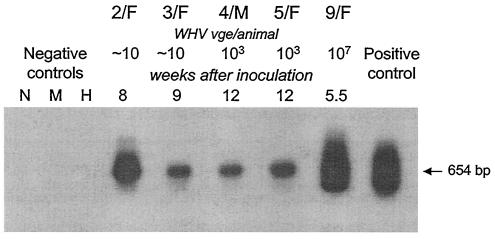

To recognize the hepadnaviral prerequisite initiating POI, normal adult woodchucks were injected with increasing doses of a serum-derived inoculum that carried the homogenous, wild-type WHV genome (WHV/tm3 inoculum) (Fig. 4). This experiment revealed that WHV doses equal to or below 103 virions caused POI with WHV DNA in serum, PBMC, and lymphoid tissues but not in the liver (Fig. 4), even when 5 μg of total liver DNA was used for direct PCR (data not shown). Conversely, all animals infected with doses of >103 virions developed acute hepatitis with WHV DNA that was readily detectable in the livers and lymphoid cells. Thus, woodchucks 1/F, 2/F, and 3/F (injected with ∼10 virions) became serum WHV DNA positive from day 7 p.i. at 10 to 102 vge/ml, and the animals carried virus in PBMC from weeks 2 to 3 p.i. onwards at concentrations of 0.05 to 0.5 vge/104 cells (Fig. 4B). These loads were essentially confirmed by real-time PCR in situations when WHV DNA signals could be detected by this technique. WHsAg and anti-WHc in serial sera (Fig. 4A) and WHV DNA in liver samples collected at weeks 6 and 12 p.i. from these animals were nonreactive (Fig. 4B and 5). WHV cccDNA was detected in PBMC from 2/F and 3/F at week 8 or 10 p.i. (Fig. 6), and a WHV sequence identical to that in the WHV/tm3 inoculum was identified in these cells. Animal 1/F, euthanized at week 18 p.i. (Fig. 4), had POI and carried WHV DNA at a concentration of 0.05 to 0.5 vge/104 cells in bone marrow and in phytohemagglutinin-stimulated splenocytes. WHV cccDNA was detectable at the same locations. The pre-S, S, C, and X gene sequences of WHV occurring in the splenocytes and plasma of this animal were identical with those in the WHV/tm3 inoculum.

FIG. 5.

WHV DNA detection in serum, PBMC, and liver tissue samples collected from woodchuck 3/F, which was injected with a dose of 10 WHV vge of the WHV/tm3 inoculum and subsequently challenged with a massive dose of the same inoculum. DNA extracted from parallel serum, PBMC, and liver biopsy samples obtained prior to inoculation (week −12), after inoculation with ∼10 vge of WHV (weeks 6 and 12 p.i.), and after challenge at week 18 p.i. with 1010 vge of the WHV/tm3 inoculum (weeks 6, 36, and 48 after challenge) were assayed for WHV DNA by direct or nested PCR by using the C gene-specific primers and Southern blotting for the detection of amplified sequences. Relevant DNA samples from a WHsAg-positive chronic carrier were included as positive controls, and samples injected with water instead of DNA (lanes D and N) and mock-treated samples (lane M) extracted in parallel with test samples were used as negative controls. Hybridization signals showed the expected 632- or 423-bp band.

FIG. 6.

Detection of WHV cccDNA in representative samples of PBMC obtained from woodchucks after inoculation with various doses of the WHV/tm3 inoculum but prior to challenge with a massive, liver-pathogenic dose of the same virus. Total DNA isolated from PBMC was digested with a single-strand-specific mung bean nuclease to eliminate WHV DNA-interrupted molecules and to amplify the DNA with PCR primers spanning the nick region of the WHV genome, as described previously (20). Nested-PCR products were analyzed by Southern blot hybridization to confirm the molecular size (654 bp) and signal specificity. Contamination controls included a sampled treated with water instead of DNA (lane N) and a mock-treated sample (lane M) tested under conditions identical to those for DNA test samples. Mung bean nuclease-treated DNA from the PBMC of a healthy woodchuck (lane H) was used as a negative control.

Interestingly, woodchucks 4/M and 5/F (injected with 103 vge) produced contrasting profiles of WHV infection. While animal 4/M established POI, woodchuck 5/F developed acute hepatitis and was WHsAg positive in its serum, with WHV DNA being readily detectable in its serum, PBMC, and liver (Fig. 4). Nevertheless, WHV cccDNA gave comparable density signals in PBMC samples from both animals obtained at week 12 p.i. (Fig. 6), and WHV sequences in these cells were identical. In the remaining four animals inoculated with >103 vge, serologically evident hepatitis developed (Fig. 4A). The disease was self-limiting in three animals, while 8/F was WHsAg positive in its serum and developed chronic hepatitis, which was superseded by HCC. In recovered woodchucks 5/F, 6/M, 7/F, and 9/F, low levels of WHV persisted in their sera, PBMC, and livers to the end of follow-up (Fig. 4B), as expected (11, 28, 33).

Primary occult WHV infection does not protect from superinfection.

Woodchucks 2115/M, 2117/M, 2/F, 3/F, and 4/M with POI and animals 5/F, 6/M, 7/F, and 9/F, which recovered from acute hepatitis, were challenged with the WHV/tm3 inoculum at a dose of 1.1 × 1010 DNase-protected vge. After challenge, all five animals with POI developed serologically evident acute hepatitis (Fig. 1B and 4). Noticeably, the disease was transient in all cases and was followed, as expected, by a residual WHV persistence in both the liver and lymphoid cells. Not surprisingly, animals 5/F, 6/M, 7/F, and 9/F were not susceptible to WHV challenge with a liver-pathogenic virus dose (Fig. 4), as previously observed (33).

DISCUSSION

In this report, by investigating the woodchuck model of hepatitis B, we show for the first time that the lymphatic system, not the liver, is the primary target of hepadnavirus when small quantities of virions invade the host. This tropism is an intrinsic property of a wild-type virus, not a result of the concealed existence of a lymphotropic variant. The infection produced is undetectable by immunovirological assays, is persistent, is transmissible to virus-naive hosts, does not induce immunoprotection, and although it is initially confined to the lymphatic system, may with time spread to the liver. We found that the quantity of the invading virus is critical in determining whether the primary infection is occult, restricted to the lymphatic system, or serologically apparent, involving the liver and causing hepatitis. In the WHV model, amounts below or near 103 virions induce POI independently of whether the virus is transmitted from a host with established occult, lymphatic-system-confined infection or from an animal with classical, chronic hepatitis that is serum WHsAg positive. The present study provides new insights into the natural history of hepadnaviral infection and consolidates previous observations implying that an asymptomatic, serologically silent infection might be procured from an exposure to a low virus dose (8, 19, 23, 39).

Previous reports have implied that lymphoid cells are the invariable site of the propagation of biologically competent WHV, even when the liver remains unaffected (9, 20). The present study proves this concept. It also delineates molecular and immunovirological properties of POI. These characteristics are significantly distinct from those of the secondary (residual) occult infection (SOI) that endures in humans and woodchucks after recovery from hepadnaviral hepatitis (28, 33, 34, 38, 46). Thus, in contrast to SOI, where protracted WHV replication occurs both in the liver and in the lymphatic system and where circulating anti-WHc and anti-WHsAg, but not WHsAg, are detectable (28, 33), POI is limited to the lymphatic system and is not accompanied by immunovirological indicators of WHV exposure. However, in both POI and SOI, WHV persists at comparable levels in serum (usually ≤100 vge/ml) and in lymphoid cells (<103 vge/μg of total DNA).

The absence of WHV in the hepatic tissues of the animals infected with WHV doses lower than or equal to 103 vge was confirmed by repeated nested-PCR-Southern blot analysis of multiple DNA preparations obtained from these livers, including testing of as much as 5 μg of total liver DNA in the direct run of the PCR. Although the potential existence of minuscule amounts of WHV DNA in intrahepatic lymphoid cells and/or residual blood within the tissue samples examined cannot be completely excluded, these virus traces, if they occurred, were not detectable by the highly sensitive assays applied in this study. To provide a definitive answer as to whether intrahepatic lymphoid cells carry virus during POI, the isolation of these cells from the appropriate livers, their expansion in vitro, and analysis for the expression of WHV DNA and virus genome replication intermediates will be required.

Animals with POI were not protected from WHV challenge and developed a transient episode of acute hepatitis. This result is consistent with our previous observations for offspring born to dams convalescent from WHV hepatitis (9) and for adult animals inoculated with low WHV doses (20). On the other hand, this result contrasts with the present (Fig. 4) and previous (33) findings for woodchucks with SOI which were unresponsive to challenge with the identical dose of the same WHV pool. This apparent discrepancy between the minuscule persistent levels of replication of virus, the susceptibilities of the animals to reinfection, and their consistent ability to effectively terminate hepatitis induced by superinfection might be explained by considering the fact that infection with small virus amounts induces a specific but anamnestic immune response. This response, although too weak to protect against challenge with a large virus dose, may have, due to continuous virus encounters, adequate recollection to mount a strong response capable of limiting liver disease produced by the reinfection.

The prerequisite virus characteristics governing the establishment of POI in the woodchuck have been clearly defined in this study. The quantity of virus usually not exceeding 103 vge was found to be decisive. However, while doses below 103 virions consistently induced POI, doses of ∼103 vge caused either POI (i.e., animal 4/M) or classical acute hepatitis (i.e., animal 5/F). Also, amounts slightly above 103 vge (e.g., ∼104 vge in 260/M) occasionally produced POI. This result suggests that the outcome of infection with borderline WHV quantities (i.e., 103 to 104 virions) is influenced not only by virus dose but also by the host milieu.

The present study reveals a significant difference (presumably 100- to 1,000-fold) between the threshold level of virus required to infect lymphoid cells and that required to infect hepatocytes. It is evident that WHV, at least at low doses, is predisposed to infect the host's lymphatic system. The nature of this tropism is not yet fully explained (14, 28). It is also unknown whether the same hierarchy in tissue tropism exists in infection with a large, liver-pathogenic dose (≥104 virions). This can be tested by determining the initial site of WHV invasion and replication by using lymphoid cells and liver biopsy samples serially collected after inoculation with such a dose but prior to the appearance of hepatitis. This approach may also elucidate the fate of virus during the long incubation period that typically precedes hepatitis.

The pathogenic and epidemiological impacts of POI need to be determined. However, since this state is associated with the trace propagation of infectious virus and viral loads similar to those in the silent infection persisting after the resolution of hepatitis (i.e., SOI), the expected consequences might also be similar. Since virus can spread from the lymphatic system to the liver with time, it might also potentially be the cause of cryptogenic hepatic pathology. Because HBV and WHV are highly compatible in their pathobiological properties, our data likely represent the blueprint for a human situation when low HBV doses invade a susceptible individual.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. D. Churchill and C. L. Trelegan for expert technical assistance.

This research was supported by grant MOP-14818 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to T.I.M.), a doctoral fellowship award from the Canadian Blood Services (to P.M.M.), and a graduate fellowship award from the Canadian Liver Foundation (to C.S.C.). T.I.M. is the Canada Research Chair (Tier 1) in Viral Hepatitis/Immunology and is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canada Foundation for Innovation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bläckberg, J., and K. Kidd-Ljunggren. 2001. Occult hepatitis B virus after acute self-limited infection persisting for 30 years without sequence variation. J. Hepatol. 33:992-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bréchot, C., V. Thiers, D. Kremsdorf, B. Nalpas, and P. Paterlini-Brechot. 2001. Persistent hepatitis B virus infection in subjects without hepatitis B surface antigen: clinically significant or purely “occult”? Hepatology 34:194-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabrerizo, M., J. Bartolomé, C. Caramelo, G. Barril, and V. Carreño. 2000. Molecular analysis of hepatitis B virus DNA in serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cells from hepatitis B surface antigen-negative cases. Hepatology 32:116-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cacciola, I., T. Pollicino, G. Squadrito, G. Cerenzia, M. E. Orlando, and G. Raimondo. 1999. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C liver disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:22-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chazouillères, O., D. Mamish, M. Kim, K. Carey, J. P. Roberts, N. L. Ascher, and T. L. Wright. 1994. “Occult” hepatitis B virus as source of infection in liver transplant recipients. Lancet 343:142-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chemin, I., F. Zoulim, P. Merle, A. Arkhis, M. Chevallier, A. Kay, L. Cova, P. Chevalier, B. Mandrand, and C. Trepo. 2001. High incidence of hepatitis B infection among chronic hepatitis cases of unknown etiology. J. Hepatol. 34:447-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chisari, F. V. 2000. Viruses, immunity, cancer: lessons from hepatitis B. Am. J. Pathol. 156:1118-1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu, C.-J., and A. S. Lok. 2002. Clinical utility in quantifying serum HBV DNA levels using PCR assays. J. Hepatol. 36:549-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coffin, C. S., and T. I. Michalak. 1999. Persistence of infectious virus in the offspring of woodchuck mothers recovered from viral hepatitis. J. Clin. Investig. 104:203-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conjeevaram, H., and A. S. Lok. 2001. Occult hepatitis B virus infection: a hidden menace? Hepatology 34:204-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodgson, P. D., and T. I. Michalak. 2001. Augmented hepatic interferon gamma expression and T-cell influx characterize acute hepatitis progressing to recovery and residual lifelong virus persistence in experimental adult woodchuck hepatitis virus infection. Hepatology 34:1049-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoofnagle, J. H., L. B. Seeff, Z. B. Buskell-Bales, H. J. Zimmerman, and the Veterans Administration Hepatitis Cooperative Study Group. 1978. Type B hepatitis after transfusion with blood containing antibody to hepatitis B core antigen. N. Engl. J. Med. 298:1379-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu, K.-Q. 2002. Occult hepatitis B virus infection and its clinical implications. J. Viral Hepat. 9:242-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin, Y.-M., N. D. Churchill, and T. I. Michalak. 1996. Protease-activated lymphoid cell and hepatocyte recognition site in the preS1 domain of the large woodchuck hepatitis virus envelope protein. J. Gen. Virol. 77:1837-1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kodama, K., N. Ogasawara, H. Yoshikawa, and S. Murakami. 1985. Nucleotide sequence of a cloned woodchuck hepatitis virus genome: evolutional relationship between hepadnaviruses. J. Virol. 56:978-986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korba, B. E., F. Wells, B. C. Tennant, P. J. Cote, and J. L. Gerin. 1987. Lymphoid cells in the spleens of woodchuck hepatitis virus-infected woodchucks are a site of active viral replication. J. Virol. 61:1318-1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korba, B. E., F. Wells, B. Baldwin, P. J. Cote, B. C. Tennant, H. Popper, and J. L. Gerin. 1989. Hepatocellular carcinoma in woodchuck hepatitis virus-infected woodchucks: presence of viral DNA in tumor tissue from chronic carriers and animals serologically recovered from acute infection. Hepatology 9:461-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laskus, T., M. Radkowski, L.-F. Wang, M. Nowicki, and J. Rakela. 1999. Detection and sequence analysis of hepatitis B virus integration in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Virol. 73:1235-1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leblebicioglu, H., D. Turan, M. Sunbul, S. Esen, and C. Eroglu. 2003. Transmission of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus by blood brotherhood rituals. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 35:210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lew, Y.-Y., and T. I. Michalak. 2001. In vitro and in vivo infectivity and pathogenicity of the lymphoid cell-derived woodchuck hepatitis virus. J. Virol. 75:1770-1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang, T. J., Y. Baruch, E. Ben-Porath, R. Enat, L. Bassan, N. V. Brown, N. Rimon, H. E. Blum, and J. R. Wands. 1991. Hepatitis B virus infection in patients with idiopathic liver disease. Hepatology 13:1044-1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang, T. J., H. E. Blum, and J. R. Wands. 1990. Characterization and biological properties of a hepatitis B virus isolated from a patient without hepatitis B virus serologic markers. Hepatology 12:204-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang, T. J., H. C. Bodenheimer, Jr., R. Yankee, N. V. Brown, K. Chang, J. Huang, and J. R. Wands. 1994. Presence of hepatitis B and C viral genomes in US blood donors as detected by polymerase chain reaction amplification. J. Med. Virol. 42:151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lok, A. S., R. H. Liang, E. K. Chiu, K. L. Wong, T. K. Chan, and D. Todd. 1991. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus replication in patients receiving cytotoxic therapy: report of a prospective study. Gastroenterology 100:1432-1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marusawa, H., S. Uemoto, M. Hijikata, Y. Ueda, K. Tanaka, K. Shimotohno, and T. Chiba. 2000. Latent hepatitis virus infection in healthy individuals with antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen. Hepatology 31:488-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mason, A., B. Yoffe, C. Noonan, M. Mearns, C. Campbell, A. Kelley, and R. P. Perrillo. 1992. Hepatitis B virus DNA in peripheral-blood mononuclear cells in chronic hepatitis B after HBsAg clearance. Hepatology 16:26-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menne, S., and B. C. Tennant. 1999. Unravelling hepatitis B virus infection of mice and men (and woodchucks and ducks). Nat. Med. 5:1125-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michalak, T. I. 2000. Occult persistence and lymphotropism of hepadnaviral infection: insights from the woodchuck viral hepatitis model. Immunol. Rev. 174:98-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michalak, T. I. 1998. The woodchuck animal model of hepatitis B. Viral Hepat. Rev. 4:139-165. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michalak, T. I., and B. Lin. 1994. Molecular species of hepadnavirus core and envelope polypeptides in hepatocyte plasma membrane of woodchucks with acute and chronic viral hepatitis. Hepatology 20:275-286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michalak, T. I., P. D. Hodgson, and N. D. Churchill. 2000. Posttranscriptional inhibition of class I major histocompatibility complex presentation on hepatocytes and lymphoid cells in chronic woodchuck hepatitis virus infection. J. Virol. 74:4483-4494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michalak, T. I., B. Lin, N. D. Churchill, P. Dzwonkowski, and J. R. B. Desousa. 1990. Hepadna virus nucleocapsid and surface antigens and the antigen-specific antibodies associated with hepatocyte plasma membranes in experimental woodchuck acute hepatitis. Lab. Investig. 62:680-689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michalak, T. I., I. U. Pardoe, C. S. Coffin, N. D. Churchill, D. S. Freake, P. Smith, and C. L. Trelegan. 1999. Occult life-long persistence of infectious hepadnavirus and residual liver inflammation in woodchucks convalescent from acute viral hepatitis. Hepatology 29:928-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michalak, T. I., C. Pasquinelli, S. Guilhot, and F. V. Chisari. 1994. Hepatitis B virus persistence after recovery from acute viral hepatitis. J. Clin. Investig. 93:230-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mulrooney, P. M., and T. I. Michalak. 2003. Quantitative detection of hepadnavirus-infected lymphoid cells by in situ PCR combined with flow cytometry: implications for the study of occult virus persistence. J. Virol. 77:970-979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Penna, A., M. Artini, A. Caballi, M. Levrero, A. Bertoletti, M. Pilli, F. V. Chisari, B. Rehermann, G. Del Prete, F. Fiaccadori, and C. Ferrari. 1996. Long-lasting memory T cell responses following self-limited acute hepatitis B. J. Clin. Investig. 98:1185-1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prieto, M., M. D. Gomez, M. Berenguer, J. Cordoba, J. M. Rayon, M. Pastor, A. Garcia-Herola, D. Nicolas, D. Carrasco, J. F. Orbis, J. Mir, and J. Berenguer. 2001. De novo hepatitis B after liver transplantation from hepatitis B core antibody-positive donors in an area with high prevalence of anti-HBc positivity in donor population. Liver Transplant. 7:51-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rehermann, B., C. Ferrari, C. Pasquinelli, and F. V. Chisari. 1996. The hepatitis B virus persists for decades after patients' recovery from acute viral hepatitis despite active maintenance of a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response. Nat. Med. 2:1104-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shiao, J., L. Guo, and M.-L. McLaws. 2002. Estimation of the risk of bloodborne pathogens to health care workers after a needlestick injury in Taiwan. Am. J. Infect. Control 30:15-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stoll-Becker, S., R. Repp, D. Glebe, S. Schaefer, J. Kreuder, M. Kann, F. Lampert, and W. H. Gerlich. 1997. Transcription of hepatitis B virus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from persistently infected patients. J. Virol. 71:5399-5407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Summers, J., J. M. Smolec, and R. Snyder. 1978. A virus similar to human hepatitis B virus associated with hepatitis and hepatoma in woodchucks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 75:4533-4537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tennant, B. C., and J. L. Gerin. 1994. The woodchuck model of hepatitis B virus infection, p. 1455-1466. In I. M. Arias, J. L. Boyer, N. Fausto, W. B. Jakoby, D. A. Schachter, and D. A. Shafritz (ed.), The liver: biology and pathobiology. Raven Press, New York, N.Y.

- 43.World Health Organization. October 2000, revision date. Hepatitis B fact sheet. W. H. O./204. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Online.] http://www.who.int/inf-fs/en/fact204.html.

- 44.Yotsuyanagi, H., Y. Shintani, K. Moriya, H. Fujie, T. Tsutsumi, T. Kato, K. Nishioka, T. Takayama, M. Makuuchi, S. Iino, S. Kimura, and K. Koike. 2000. Virologic analysis of non-B, non-C hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: frequent involvement of hepatitis B virus. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1920-1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yotsuyanagi, H., K. Yasuda, S. Iino, K. Moriya, Y. Shintani, H. Fujie, T. Tsutsumi, S. Kimura, and K. Koike. 1998. Persistent viremia after recovery from self-limited acute hepatitis B. Hepatology 27:1377-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuki, N., T. Nagaoka, M. Yamashiro, K. Mochizuki, A. Kaneko, K. Yamamoto, M. Omura, K. Hikiji, and M. Kato. 2003. Long-term histologic and virologic outcomes of acute self-limited hepatitis B. Hepatology 37:1172-1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]