Abstract

Objective

The mixing of alcohol and energy drinks (AMEDs) is a trend among college students associated with higher rates of heavy episodic drinking and negative alcohol-related consequences. The goals of the present study were to take a person-centered approach to identify distinct risk profiles of college students based on AMED-specific constructs (expectancies, attitudes, and norms) and examine longitudinal associations between AMED use, drinking, and consequences.

Method

A random sample of incoming freshmen (n = 387, 59% female) completed measures of AMED use, AMED-specific expectancies, attitudes, and normative beliefs, and drinking quantity and alcohol-related consequences. Data were collected at two occasions: spring semester of freshmen year and fall semester of sophomore year.

Results

Latent profile analysis (LPA) identified four subgroups of individuals: occasional AMED, anti-AMED, pro-AMED, and strong peer influence. Individuals in the pro-AMED group reported the most AMED use, drinking, and consequences. There was a unique association between profile membership and AMED use, even after controlling for drinking.

Conclusions

Findings highlighted the importance of AMED-specific expectancies, attitudes, and norms. The unique association between AMED risk profiles and AMED use suggests AMED use is a distinct behavior that could be targeted by AMED-specific messages included in existing brief interventions for alcohol use.

Keywords: alcohol-energy drink cocktails (AMEDs), college students, high-risk drinking, alcohol-related consequences

Recent studies of college student alcohol use suggest heavy-episodic drinking (HED) continues to be a major health problem that is associated with academic, legal, and health problems (Grant and Dawson, 1997; Hingson et al., 2009; NIAAA, 2006; Read et al., 2008; Shillington and Clapp, 2006). The consumption of alcohol mixed with energy drinks (AMEDs; e.g., Red Bull and vodka) has received increased research attention due to its association with HED (Marzell, 2011; Miller, 2008; Price et al., 2010; Velazquez et al., 2012). For example, research shows roughly one quarter of college students consume AMEDs in a typical month and that AMED users engage in HED significantly more often than non-AMED users (O'Brien et al., 2008).

Although the majority of existing studies have focused on AMED use as a correlate of HED (O'Brien et al., 2008; Thombs et al., 2010), recent research suggests that it is a unique high-risk behavior worthy of attention in its own right. For example, research shows college students who were frequent AMED users were two times more likely to meet criteria for alcohol dependence after controlling for alcohol use, Greek involvement, and family history of alcohol problems (Arria et al., 2011). Other studies have shown AMED users were more likely to use prescription drugs for recreational reasons and experience consequences such as being taken advantage of sexually, riding with an intoxicated driver, and experiencing increased injuries (Arria et al., 2010; Brache and Stockwell, 2011; O'Brien et al., 2008; Thombs et al., 2010; Woolsey et al., 2010). Finally, studies examining predictors of AMED use have found that AMED peer norms, expectancies, and self-concept (e.g., being popular or exciting) were all associated with higher levels of AMED use (Jones et al., 2012; Marzell, 2011). For example, higher perceived peer approval of AMED use was associated with more AMED use (Marzell, 2011). Similarly, more positive expectancies about AMED use (e.g., reducing hangovers, being able to party longer) were associated with higher levels of AMED use.

Previous research has explored the benefits of identifying variables that are correlated with AMED use in order to inform prevention efforts. An alternate approach is to identify specific individuals who are at the highest risk of experiencing problems. Thus a “person-centered approach” allows for the identification of distinct subgroups of individuals who differ from one another based on their AMED expectancies, attitudes, and norms (i.e., risk profiles). Further, the person-centered approach permits an examination of the relationship between the different risk profiles and high-risk drinking behaviors (e.g., greater AMED use, HED, and alcohol related-consequences). In combination, the identification of varying risk profiles and the examination of the relationships between risk profiles and behavioral outcomes would provide essential information for the development of targeted intervention strategies.

Therefore, the objectives of the current analysis were to: 1) utilize a person-centered approach to identify distinct risk profiles using AMED-specific expectancies, attitudes, and norms based on previous research by Marzell (2011), 2) use a prospective design to determine how the risk profiles are related to AMED use, HED, and alcohol-related consequences at a follow-up period, and 3) determine whether the association between profile membership and AMED use and alcohol-related consequences can be partially or fully explained by differences in drinking. We hypothesized that several unique risk profiles will be identified. For example, we hypothesized that profiles characterized by more positive AMED-specific expectancies, attitudes, and norms, will report more AMED use, more HED, and more consequences at follow up. Based on previous work showing associations between AMED use and HED (e.g., Marzell, 2011) and problem drinking patterns (Arria et al., 2011), we expected that associations between AMED risk-profiles and consequences will be partially rather than fully explained by drinking (i.e., AMED risk profile will be a unique predictor of HED and consequences).

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 387 first-year college students from a large, public university in the northeastern United States drawn from the control group of a larger intervention study who self-identified as drinkers (criteria described below). The mean age of participants was 18.7 (SD=.45), with 59.2% identifying as female. Racial characteristics were as follows, and were representative of the larger campus community: 90.7% White/Caucasian, 3.4% Black or African American, 2.1% Asian, 2.1% American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 1.7% other. In addition, 4.2% of the sample identified as Hispanic/Latino.

Procedure

Participants were randomly selected from the university registrar's database of first-year students. Invitation letters explaining the study, procedures, and compensation were mailed to all potential participants along with a URL and Personal Identification Number (PIN) for accessing the survey. The response rate was 75.4%. In addition to the mailed invitations, e-mail invitations were sent to participants’ university email addresses, and reminder emails and postcards encouraged participation. Alcohol use was assessed at baseline and participants who reported no current alcohol use (i.e., I have never tried alcohol or I have tried alcohol, but currently don't drink) were excluded. Participants received $15 for completing the baseline survey and $35 for completing the follow-up survey.

After providing informed consent, participants completed a web-based survey at two time points: 1) baseline (spring of their first year of college), and 2) follow up (during the fall of their second year). The attrition rate between baseline and follow up was 9.8%; therefore, over 90% of the original sample completed the follow-up assessments. Chi square analyses determined that there were no significant differences in AMED use at baseline when comparing those who completed the study to those who were lost to follow up. The local institutional review board approved all study procedures, and treatment of participants was in compliance with APA ethical guidelines.

Measures

AMED-Specific Latent Profile Indicators

The following latent profile indicators were measured at baseline, during the spring of the first year of college.

AMED Expectancies

Expectancies regarding AMED use were assessed based on previous research (Woolsey et al., 2010; Marzell, 2011). Participants were asked to indicate their agreement about whether they would drink alcohol mixed with energy drinks for the following reasons: 1) “because it makes partying better;” 2) “because it allows me to drink more and feel less drunk (i.e., less drowsy);” 3) “because it allows me to party longer when I have had a tiring day (e.g., studying, working, and tailgating);” and 4) “because [I have] less of a hangover the next day.” Response options were on a five-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (-2) to strongly agree (2). These four items were summed to create a composite variable for expectancies, (α = 0.90).

AMED Attitudes

Attitudes regarding AMED use were assessed based on previous research (Woolsey et al., 2010; Marzell, 2011). Participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with 2 statements regarding their attitudes about AMEDs on a five-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (-2) to strongly agree (2). The items were: “I like the way combining alcohol and energy drinks makes me feel” and “I feel favorably about consuming alcohol mixed with energy drinks.” These two items were highly correlated (r=.69, p<.01).

AMED Descriptive and Injunctive Normative Beliefs

Both descriptive and injunctive peer normative beliefs were assessed. To assess descriptive peer norms, participants were asked the number of AMEDs they believe their closest friends consumed on each day of a typical week within the past 30 days using an adapted version of the Drinking Norms Rating Form (DNRF; Baer et al., 1991). Survey responses for Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday were summed to result in a total number of AMEDs perceived to be consumed by participants’ closest friends during a typical week.

To assess injunctive norms, participants were asked the degree to which they believed their closest friends would approve of their AMED use. Participants responded to the item, “My closest friends would approve of me drinking alcohol mixed with energy drinks,” on a five-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (-2) to strongly agree (2).

Longitudinal AMED- and Drinking-related Outcomes

The following outcomes were measured at follow up, during the fall of the second year of college.

AMED use

AMED use was measured using items modified from the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al., 1985). Participants indicated how many AMEDs they consumed on a typical Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, etc. These responses were summed to create a measure of the number of AMEDs consumed in a typical week.

HED

HED was assessed in two ways: frequency of heavy drinking and typical weekly drinking. The Quantity/Frequency/Peak questionnaire (QFP; Dimeff et al., 1999; Marlatt et al., 1998) was used to assess frequency of heavy drinking. Participants were asked to report the number of times in the past 30 days that they “got drunk, or very high from alcohol.”

In addition to heavy drinking, participants completed the DDQ as above with respect to alcohol-only use. They reported how many alcoholic drinks they consumed on each day of a typical week, and these responses were summed to create a measure of typical weekly drinking. A standard drink chart was provided (12 oz. beer, 10 oz. wine cooler, 4 oz. wine, 1 oz. 100-proof liquor or 1 ¼ oz. 80-proof liquor).

Alcohol-related consequences

An abbreviated version of the Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (YAAPST; Hurlbut and Sher, 1992) measured negative alcohol-related consequences. Respondents indicated the frequency of occurrence of 17 consequences (e.g. blacking out, having sex with someone they wouldn't ordinarily have sex with, receiving a lower grade on an exam, etc.) in the past year. These consequences were selected because they typically have a prevalence rate of at least 5% among college student samples (Mallett et al., 2011). Response options ranged from (0) never to (8) 40 or more times. The YAAPST items were summed to create a composite consequence score.

Data Analyses

The goals of the analyses were three-fold. The first was to identify distinct risk profiles of college student drinkers with respect to their expectancies, attitudes, and normative beliefs regarding AMED use, and the second was to assess whether individuals fitting these risk profiles differed in terms of AMED use, heavy and typical weekly drinking, and negative alcohol-related consequences at the longitudinal follow up assessment. If differences in AMED use or consequences emerged between profiles, the final goal was to determine whether drinking or a combination of drinking and AMED use could explain these differences.

To achieve the first aim of the analyses, latent profile analyses (LPA) were conducted following the procedures outlined by Lanza and colleagues (2007), using the software program Mplus (Version 6.1). The goal of LPA is to identify subgroups of individuals who are most similar to each other with respect to selected indicators (i.e., expectancies, attitudes, and norms) while maximizing between-group differences on these indicators. See Lanza et al. (2007) for a full description of LPA procedures. The Akaike Information Criteria (AIC; Akaike, 1974) and the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC; Schwartz, 1978) are indices of model fit for LPA, and smaller values reflect better fit. Log likelihood values are another index of model fit. In addition to AIC and BIC, the entropy value, which can range from 0 to 1, is an indication of the classification quality, or how accurately individuals are classified into the “correct” profile. Finally, model convergence and practical utility of the identified profiles must also be considered when determining the best solution for the data.

Once a solution has been fit to the data and the number of latent profiles has been determined, descriptive characteristics can be examined. Posterior probabilities can be used to assign the “most likely” profile for each individual. Previous work has used this “classify and analyze” approach when the entropy value is greater than .80 (Agrawal et al., 2007).

All individuals in the sample were assigned to their most likely profile and profiles were compared in terms of the outcomes of interest: AMED use, frequency of heavy drinking and typical weekly drinking, and alcohol-related consequences. One-way ANOVA was used to assess whether there were significant differences between groups with respect to these outcomes. If significant effects were found, Tukey's HSD test was used to make post-hoc comparisons between profile means.

The last step was to conduct additional one-way ANOVA to determine the source of any between-profile differences in AMED use or consequences. For example, if between-profile differences in AMED use were identified, a follow-up one-way ANOVA controlling for drinking was conducted to determine if this difference could be explained by differences in drinking at follow up. A similar follow-up ANOVA was conducted to determine if profile differences in consequences could be explained either by AMED use, by drinking, or by a combination of AMED use and drinking.

Results

Aim 1: Identification of Latent Profiles

Four indicators were included in the LPA: expectancies, attitudes, peer descriptive norms, and peer injunctive norms. Starting with a one-profile model, the AIC, BIC and log likelihood values decreased as additional profiles were added. The four-profile model was selected as the best fit for the data with the most interpretability. Table 1 lists AIC, BIC, log likelihood, and entropy values for the one through five-profile solutions. All models converged normally. The final four-profile solution had an entropy value of .86, indicating good classification quality.

Table 1.

AIC, BIC, log likelihood, and entropy values for the one- through five-profile solutions.

| AIC | BIC | Log likelihood | Entropy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One profile | 7311.06 | 7342.73 | -3647.53 | |

| Two profiles | 7034.68 | 7086.14 | -3504.34 | .97 |

| Three profiles | 6835.80 | 6907.05 | -3399.90 | .84 |

| Four profiles | 6769.82 | 6860.87 | -3361.91 | .86 |

| Five profiles | 6681.21 | 6792.04 | -3312.60 | .88 |

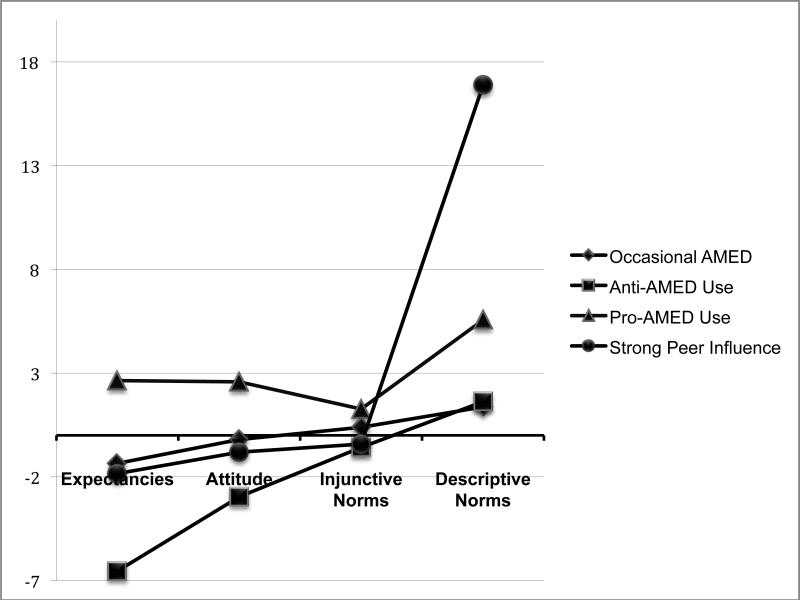

Indicator means were examined within each profile in order to qualify the characteristics of each of the profiles. Figure 1 shows the means on each of the four indicators for each of the profiles.

Figure 1.

Graph of four profiles with corresponding mean values for expectancies, attitudes, and injunctive and descriptive norms.

Profile one comprised 53.7% (n=208) of the sample and was labeled occasional AMED. Individuals fitting into this profile reported neutral expectancies, attitudes, and injunctive normative beliefs about AMED use. These individuals were neither strongly opposed to or strongly in favor of AMED consumption. In addition, they believed that their closest friends consumed a small number of AMEDs per week (1.37 drinks).

Profile two was labeled anti-AMED use and made up 30.5% (n=118) of the sample. This profile had highly negative expectancies (-6.54), attitudes (-2.96), and injunctive normative beliefs (-.58) about AMED use. With respect to descriptive norms, they perceived that their closest friends were consuming a small number of AMEDs per week (1.62 drinks).

Profile three comprised the smallest percentage of the sample (5.2%; n=20). This group had the most positive attitudes (2.58) and injunctive normative beliefs (1.27) of any profile in the sample. Their descriptive normative beliefs were moderately high (5.56), and their expectancies were neutral. This profile was labeled pro-AMED use.

Profile four was also a smaller percentage of the sample (10.6%, n=41), and reported the most discordant beliefs. Their expectancies and attitudes were moderately negative (-1.84 and -.81, respectively). Incongruent with their personal feelings, their injunctive normative beliefs were moderately positive (.42), and they perceived that their closest friends consumed a high number (16.87) of AMEDs per week. This final profile was labeled strong peer influence.

Aim 2: Association Between Latent Profiles and Longitudinal Outcomes: AMED Use, Drinking, and Consequences

With respect to demographic variables, chi square analyses revealed there was no significant association between profile membership and gender or racial background. Table 2 lists means and standard deviations for typical weekly AMED use, typical weekly drinking, and alcohol-related consequences at follow up by profile. Significant differences are discussed below.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for AMED Use, Drinking, and Consequences by Profile

| Occasional AMED (n = 208) | Anti-AMED (n = 118) | Pro-AMED (n = 20) | Strong Peer Influence (n = 41) | F (df) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weekly AMED | .7 (1.9) | .2 (.8) | 1.7 (2.9)a | 1.5 (3.2)a | 6.23 (3,344)* |

| Heavy drinking | 2.1 (1.5) | 1.8 (1.4) | 2.8 (1.3)a | 2.1 (1.2) | 3.06 (3,345)* |

| Weekly drinking | 13.3 (11.2)a | 10.0 (8.4) | 17.7 (10.4)a | 12.7 (8.0) | 4.12 (3,345)* |

| Consequences | 17.4 (12.5) | 13.9 (11.2) | 22.9 (14.6)a | 14.9 (8.8)b | 4.09 (3,344)* |

p<.01

Denotes a significant (p<.05) and positive mean difference for a given profile when compared to the anti-AMED profile.

Denotes a significant (p<.05) and negative mean difference for a give profile when compared to the pro-AMED profile.

AMED use

There were significant associations between profile membership and typical weekend AMED use (F(3,344)=6.23, p<.01). Post-hoc comparisons revealed that participants in the pro-AMED and the strong peer influence profiles reported significantly more weekly AMEDs (1.51 and 1.29, respectively) than participants in the anti-AMED profile. There were no significant differences between members of the occasional AMED profile and any of the other three profiles with respect to weekly AMED use.

Heavy and typical weekly drinking

There were significant differences in frequency of heavy drinking by profile membership (F(3,345)=3.06, p<.05). Post-hoc comparisons showed that participants in the pro-AMED profile reported 1.05 more occasions of heavy drinking than participants in the anti-AMED profile.

There was a significant association between profile membership and typical weekly drinking (F(3,345)=4.12, p<.01). Post-hoc comparisons revealed that participants in the occasional AMED profile reported 3.28 more weekly drinks than participants in the anti-AMED profile. Participants in the pro-AMED profile reported 7.63 more weekly drinks than participants in the anti-AMED profile.

There were no significant differences in frequency of drunkenness or weekly drinking between participants in the strong peer influence profile and any of the other profiles.

Consequences

There were significant differences in alcohol-related consequences by profile (F(3,344)=4.09, p<.01). Post-hoc comparisons showed that members of the anti-AMED profile reported fewer consequences than the pro-AMED profile (mean difference=-6.52, p<.05). Members of the strong peer influence profile also reported significantly fewer consequences than the pro-AMED profile (mean difference = -6.72, p<.05). No other mean differences in consequences were significant.

Aim 3: Unique Associations between Profiles and AMED Use and Consequences

AMED Use

Two separate ANOVA tested whether the association between profile membership and typical weekly AMED use was significant after controlling for drinking (the first for heavy drinking and the second for typical weekly drinking). The association between profile and AMED use remained significant in both cases (heavy drinking, F(3,342)=5.03, p<.01; typical weekly drinking, F(3,342)=4.73, p<.01).

Consequences

The final model tested whether profile differences in consequences could be explained by differences in AMED use and/or drinking. When including heavy drinking, typical weekly drinking, and AMED use as covariates in the ANOVA model, profile membership was no longer associated with consequences (F(3,340)=1.72, p=ns). Heavy drinking (F(1,340)=23.70, p<.001) and typical weekly drinking (F(1,340)=29.69, p<.001) were significantly associated with consequences, while typical AMED use was not (F(1,340)=1.00, p=ns).

Discussion

The current study used a person-centered approach to identify individuals varying in terms of their risk profiles based on AMED-specific expectancies, attitudes, and norms. Latent profile analysis identified four unique risk profiles based on these psychosocial constructs.

The largest profile (occasional AMED), made up of over half of the sample, had consistently neutral feelings about AMED use. The next largest profile, consisting of about one third of the sample, was the anti-AMED profile. Only a small group of students fit the pro-AMED profile. Perhaps the most interesting profile that emerged was the strong peer influence profile. Individuals fitting this profile reported negative feelings about AMED use, but believed that high levels of AMED use were normative among their peers. Previous work by Mallett and colleagues (2009) examined several types of normative beliefs (descriptive and injunctive with respect to both the same-sex “typical college student” and closest friends) in conjunction with intrapersonal constructs (attitudes and expectancies) in a variable-centered framework. The authors found that when including intrapersonal factors in their model, closest friend drinking norms were the only significant predictors of college student drinking. Consistent with those findings, the results of the present study suggest that AMED-specific closest friend norms may be particularly influential for a specific subgroup of individuals.

The longitudinal assessment determined how the risk profiles were related to behavioral outcomes. Profile membership was related to AMED use, HED, and related consequences. The pro-AMED profile appeared to be at the highest risk for AMED use and HED, reporting high levels of AMED use, and both measures of drinking. Members of this profile also reported high levels of consequences. Conversely, the anti-AMED profile reported the lowest levels of risk, with lower levels of AMED use, heavy and weekly drinking, and fewer consequences. Interestingly, the strong peer influence group did not differ substantially from the other profiles in terms of drinking or consequences, but did report higher levels of weekly AMED use. Similar to previous alcohol research showing that perceptions of closest friends’ alcohol consumption are a strong predictor of drinking (Mallett et al., 2009), it appears that students in the profile reporting the strongest AMED-specific normative influences were more likely to consume AMEDs. In addition, profile membership was significantly associated with typical weekly AMED use, even after controlling for drinking. This supports previous work showing that AMED use is a high-risk behavior distinct from drinking (Arria et al., 2011).

In contrast, the association between risk profile membership and consequences was fully explained by heavy and weekly drinking. There are several possible explanations for the attenuation of the association between profile membership and consequences. One plausible explanation is that the items used to measure consequences do not sufficiently capture consequences that may be more likely to result from combined AMED use. The YAAPST has been criticized for being gender biased and for lack of sensitivity to less severe consequences (Read et al., 2006). Therefore, it is possible that profile differences could exist in terms of consequences that are more likely to result from AMED use. For example, AMED use may be more likely to lead to shorter-term physiological problems (e.g., rapid heartbeat, loss of sleep) or longer-term problems that are not assessed by the YAAPST (e.g., nonmedical prescription drug use; Arria et al., 2010).

Taken together, the results from this person-centered analysis add to limited existing research identifying the relationship between psychosocial predictors and AMED use (Jones et al., 2012; Marzell, 2011) but offer additional insight in terms of the existence of distinct profiles of students. Students in the profile characterized by the most positive expectancies and attitudes were at the greatest risk for AMED use, HED, and related consequences. The present person-centered approach allowed for the identification of a subgroup of students who perceived strong AMED-specific normative influences and were also significantly more likely to be AMED users, but did not differ from other lower-risk profiles in terms of alcohol use. This finding emphasizes the complex and interrelated nature of drinking, AMED use, and related risk behaviors and the benefits of examining the relationships between these constructs at the person-centered level.

Implications

Findings from the present study have relevant implications for prevention efforts. The current study adds to the existing literature by examining psychosocial predictors of AMED use from a person-centered perspective, and assessing how risk profile membership is related to AMED use and alcohol-related harm longitudinally. Interventions typically tend to focus on high-risk drinking in general and not AMED use (Larimer and Cronce, 2007). The present findings suggest that information about AMED use should be included as part of comprehensive intervention efforts. Specific interventions such as brief motivational feedback interviews (e.g., BASICS; Larimer et al., 2001) or parent-based interventions (Turrisi et al., 2001; 2007; Ichiyama et al., 2009) may benefit from including information about AMED use, HED, and related consequences. Further, the identification of individuals’ risk profiles based on AMED-specific psychosocial variables provides information that can be used to improve targeted intervention efforts.

For example, within this sample there was a small group of high-risk individuals (the pro-AMED profile) that reported positive expectancies and attitudes about AMED use. This group represents a high-risk segment of the population that typically consumes a substantial amount of AMEDs, drinks heavily, and experiences higher levels of alcohol-related consequences. For this subgroup, an intervention approach designed to specifically address AMED-related expectancies and attitudes might be appropriate. In contrast, the strong peer influence profile would call for a different intervention strategy. Because this group's expectancies and attitudes are already negative, these constructs would not be the best avenue for change. Instead, addressing normative misperceptions about how prevalent AMED use is among their friends would be expected to be more effective. Therefore, the findings from the present study may offer the ability to identify high-risk individuals (e.g., drinkers fitting the pro-AMED profile) as a screening tool for programs designed to reduce the extent of college AMED use and HED.

In addition to these implications for prevention work, the present findings offer justification for the continued examination of AMED use as a distinct high-risk behavior, rather than assuming that AMED use is simply part of a constellation of high-risk behaviors that include HED. The present finding that individuals’ AMED-specific profiles were associated with AMED use even after controlling for drinking suggests that students’ psychosocial orientations toward AMED use may provide unique information, over and above drinking, that can be used to tailor intervention programs. Future work should explore the extent to which AMED-specific profiles are associated with longer-term problems, such as the risk for alcohol dependence (Arria et al., 2011).

Limitations

The present study is not without limitations. It should be noted that the sample is largely homogeneous with regard to race and ethnicity (90% Caucasian and less than 5% Hispanic/Latino) and consists of first-year students followed into their second year of college. Although previous research has shown that white, male, first-year students are at the most risk for harm associated with consuming energy drinks alone or in combination with alcohol (Miller, 2008; O'Brien et al., 2008; Woolsey et al., 2010), more work needs to be done in order to extend conclusions to more inclusive college populations.

In addition the study included two occasions of data collection but did not follow students into the third or fourth years of college. It is not clear how attitudes, expectancies, and normative perceptions might change within profiles over time. Multiple data collections assessing these variables over time would allow for modeling changes within profiles over time (e.g., growth mixture modeling), as well as analyzing how the associations among profile membership, AMED use, HED, and consequences might change. In addition, more sophisticated measures of consequences specific to AMED use (e.g., rapid heartbeat, prescription drug abuse) would clarify whether profile membership and consequences are uniquely associated.

Finally, the present study asked participants to report their drinking behaviors retrospectively, which may result in self-report bias. Future work that examines AMED use at the event level may provide more detailed information about the behavior and its relationship to HED and specific consequences.

Conclusions

AMED use is prevalent among college students and is worthy of further exploration as a distinct high-risk behavior that is associated with long-term problems. The present study was the first to use a person-centered approach to examine AMED-specific psychosocial variables (expectancies, attitudes, and beliefs) and how they operate together within individuals to influence AMED use and related outcomes. Linking profile membership to longitudinal AMED use after controlling for drinking was a major strength of the study. The findings from this person-centered study can be used to inform college alcohol interventions tailored for specific subgroups of students.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant R01AA015737 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism awarded to Rob Turrisi, PhD. The authors would like to thank Aimee Read, Kelly Guttman, and Sarah Favero for their assistance with the project.

References

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Heath AC. A latent class analysis of illicit drug abuse/dependence: Results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Addiction. 2007;102:94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Autom Control. 1974;19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Kasperski SJ, O'Grady KE, Vincent KB, Griffiths RR, Wish ED. Increased alcohol consumption, nonmedical prescription drug use, and illicit drug use are associated with energy drink consumption among college students. J Addict Med. 2010;4:74–80. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181aa8dd4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Kasperski SJ, Vincent KB, Griffiths RR, O'Grady KE. Energy drink consumption and increased risk for alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:365–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01352.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer ME. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. J Stud Alcohol. 1991;52:580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brache K, Stockwell T. Drinking patterns and risk behaviors associated with combined alcohol and energy drink consumption in college drinkers. Addict Behav. 2011;36:1133–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24, 1998-2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, Sher KJ. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. J Amer Coll Health. 1992;41:49–58. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichiyama M, Fairlie AM, Wood MD, Turrisi R, Francis D, Ray A, Stanger L. A randomized trial of a parent-based intervention with incoming college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;16:67–76. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SC, Barrie L, Berry N. Why (not) alcohol energy drinks? A qualitative study with Australian university students. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2012;31:281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Collins LM, Lemmon DR, Schafer JL. PROC LCA: A SAS procedure for latent class analysis. Struct Equ Modeling. 2007;14:671–694. doi: 10.1080/10705510701575602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999-2006. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Anderson BK, Fader JS, Kilmer JR, Palmer RS, Cronce JM. Evaluating a brief alcohol intervention with fraternities. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:370–380. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Bachrach RL, Turrisi R. Examining the unique influence of interpersonal and intrapersonal drinking perceptions on alcohol consumption among college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:178–185. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Marzell M, Varvil-Weld L, Turrisi R, Guttman K, Abar C. One-time or repeat offenders? An examination of the patterns of alcohol-related consequences experienced by college students across the freshman year. Addict Behav. 2011;36:508–511. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, Somers JM, Williams E. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzell M. Reducing high-risk college drinking: Examining the consumption of alcohol-energy drink cocktails among college students. Penn State University; University Park: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Miller K. Energy drinks, race, and problem behaviors among college students. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:490–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mplus (Version 6.1) [Computer software] Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA Initiative on underage drinking. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/aboutNIAAASponsored Programs/underage.htm.

- O'Brien MC, McCoy TP, Rhodes SD, Wagoner A, Wolfson M. Caffeinated cocktails: Energy drink consumption, high-risk drinking, and alcohol-related consequences among college students. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:453–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price SR, Hilchey CA, Darredeau C, Fulton HG, Barrett SP. Energy drink co administration is associated with increased reported alcohol ingestion. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:331–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Beattie M, Chamberlain R, Merrill JE. Beyond the “binge” threshold: Heavy drinking patterns and their association with alcohol involvement indices in college students. Addict Behav. 2008;33:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2006;67:169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6(2):461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Shillington AM, Clapp JD. Heavy alcohol use compared to alcohol and marijuana use: Do college students experience a difference in substance use problems? J Drug Educ. 2006;36:91–103. doi: 10.2190/8PRJ-P8AJ-MXU3-H1MW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, O'Mara RJ, Tsukamoto M, Rossheim ME, Weiler RM, Merves ML, Goldberger BA. Event-level analyses of energy drink consumption and alcohol intoxication in bar patrons. Addict Behav. 2010;35:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Jaccard J, Taki R, Dunnam H, Grimes J. Examination of the short-term efficacy of a parent intervention to reduce college student drinking tendencies. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15:366–373. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Mastroleo N, Mallett K, Larimer M, Kilmer J. Examination of the mediational influences of peer norms, parent communications, and environmental influences on heavy drinking tendencies in athletes and non-athletes. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:453–461. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velazquez CE, Poulos NS, Latimer LA, Pasch KE. Associations between energy drink consumption and alcohol use behaviors among college students. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolsey C, Waigandt A, Beck NC. Athletes and energy drinks: reported risk-taking and consequences from the combined use of alcohol and energy drinks. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2010;22:65–71. [Google Scholar]