Abstract

Rationale

Receptor mechanisms underlying the behavioral effects of clinically used nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists have not been fully established.

Objective

Drug discrimination was used to compare receptor mechanisms underlying the effects of smoking cessation aids.

Methods

Separate groups of male C57BL/6J mice discriminated 0.56, 1, or 1.78 mg/kg of nicotine base. Nicotine, varenicline, and cytisine were administered alone, in combination with each other, and in combination with mecamylamine and dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE). Midazolam and morphine were tested to examine sensitivity to non-nicotinics.

Results

The ED50 value of nicotine to produce discriminative stimulus effects systematically increased as training dose increased. Varenicline and cytisine did not fully substitute for nicotine and, as compared with nicotine, their ED50 values varied less systematically as a function of nicotine training dose. Morphine did not substitute for nicotine, whereas midazolam substituted for the low and not the higher training doses of nicotine. As training dose increased, the dose of mecamylamine needed to produce a significant rightward shift in the nicotine dose-effect function also increased. DHβE antagonized nicotine in animals discriminating the smallest dose of nicotine. Varenicline did not antagonize the effects of nicotine, whereas cytisine produced a modest though significant antagonism of nicotine.

Conclusions

These results suggest that differences in pharmacologic mechanism between nicotine, varenicline, and cytisine include not only differences in efficacy at a common subtype of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, but also differential affinity and/or efficacy at multiple receptor subtypes.

Keywords: agonist, antagonist, cytisine, dihydro-β-erythroidine, drug discrimination, efficacy, mecamylamine, mouse, nicotine, varenicline

INTRODUCTION

The use of tobacco products in the form of cigarette smoking results in respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and premature death. Abstinence can be facilitated by treatment with various nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ligands including nicotine, varenicline, and cytisine. These drugs, as well as the endogenous ligand acetylcholine, bind at the interface of two of the five protein subunits (i.e. nicotinic acetylcholine receptors) comprising an ion channel permeable to sodium, potassium, and calcium (Coe et al. 2005; Gotti et al. 2010). Various brain subunits (i.e. nine α and three β) are differentially combined to produce multiple subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. In cell lines transfected with various receptor subtypes including heteromeric (e.g. α4β2 and α3β4) and homomeric receptors (e.g. α7), nicotine, varenicline, and cytisine have the same rank order binding affinity at the various subtypes, yet differ in relative affinity (Grady et al. 2010). When measuring current in cells transfected with α4β2 receptors, the maximum current evoked by varenicline and cytisine is less than that evoked by nicotine, demonstrating differences in efficacy among drugs at this particular subtype (Coe et al. 2005; Mihalak et al. 2006). Differences in relative binding affinity and efficacy among these and other nicotinic drugs could translate into different in vivo effects and ultimately therapeutic effectiveness.

Inasmuch as drug discrimination is selective for the receptor mechanism(s) by which a training drug produces its effects, the assay is particularly useful for establishing receptor mechanisms in vivo. In two-choice discriminations between nicotine and saline, varenicline and cytisine substituted fully for nicotine in some studies (Pratt et al. 1983; Craft and Howard 1988; Reavill et al. 1990; Chandler and Stolerman 1997; Rollema et al. 2007; Cunningham et al. 2012) and partially for nicotine in other studies (Smith et al. 2007; LeSage et al. 2008; Jutkiewicz et al. 2011). Partial effects of varenicline and cytisine were attributed to low efficacy; this interpretation was supported by attenuation of the effects of nicotine by varenicline and cytisine (LeSage et al. 2008). Examining the effects of drugs across a range of training doses is an additional strategy that has been used to demonstrate relationships between agonist efficacy and behavioral effects for other drug classes such as μ opioids (Young et al. 1992; Zhang et al. 2000). While training dose of nicotine has been varied in previous studies (Smith and Stolerman 2009), this strategy has not been explicitly used in an attempt to differentiate multiple nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists on the basis of receptor mechanism including agonist efficacy.

Here, the effects of nicotine, varenicline, and cytisine were examined in separate groups of male C57BL/6J mice discriminating one of three doses of nicotine base (0.56, 1, or 1.78 mg/kg i.p.). Training doses were initially chosen from the range of doses used in a previous drug discrimination study (Stolerman et al. 1999) and the potency of nicotine to decrease rate of fixed ratio responding in mice (Cunningham and McMahon 2011). In addition to comparing the maximum effects, potencies, and slopes of dose-effect functions for different drugs at each training dose, the mechanism of action was examined by combining drugs with the non-competitive, non-selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist mecamylamine and the competitive β-subunit containing receptor antagonist dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE). Further tests with non-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor drugs (morphine and midazolam) were conducted in order to determine the extent to which nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonism was responsible for discriminative stimulus effects.

METHODS

Subjects

Twenty-four male C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were purchased at 8 weeks of age (approximately 15 g) and were housed individually on a 14/10-h light/dark cycle. Mice were maintained at 85% of free-feeding weight and received up to 0.6 cc of 50% condensed milk during experimental sessions and 2.5 g of food (Dustless Precision Pellets 500 mg, Rodent Grain-Based Diet, Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ) per day after sessions; water was available ad libitum in the home cage. Mice were habituated to the experimental room for 7 days before the first experimental session, and experimental sessions were conducted during the light period. Mice were maintained, and experiments were conducted in accordance with, the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and the National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute for Laboratory Animal Research, 2011).

Apparatus

Commercially available mouse operant conditioning chambers (MedAssociates, St. Albans, VT) were placed in ventilated, sound-attenuating enclosures. The ceiling of each operant conditioning chamber contained a light (i.e. house light), the side of one wall contained a recessed hole (2.2-cm diameter), and the opposite wall contained three evenly spaced (approximately 5.5 cm apart) identical holes. The center of each hole was positioned 1.6 cm from the floor. The wall with the single hole contained a dipper from which 0.01 cc of condensed milk could be delivered from a tray positioned outside the operant conditioning chamber. The holes on the opposite wall contained a photo beam and a light in each hole. An interface (MedAssociates) connected the operant conditioning chambers to a computer, and experimental events were controlled and recorded with Med-PC software (Med Associates).

Discrimination training

Experimental sessions were conducted once daily, seven days per week. During the first four days of training the lights inside the nose-poke holes were illuminated; a single response on either the left or right hole (i.e. disruption of the photobeam under a schedule of continuous reinforcement) resulted in 10-s access to 0.01 cc of milk from the hole on the opposite wall. Responding on the center hole had no programmed consequence. During the 10-s period of milk access, the lights inside the nose-poke holes were extinguished, the house light was illuminated, and disruption of the photobeams had no programmed consequence. If 100 milk presentations were obtained before 60 minutes, then the response requirement was systematically increased to a fixed ratio 10 (FR10) over days. Thereafter, responding was maintained under an FR10 schedule of milk presentation and each session was divided into a 10-min pretreatment period, during which time responses had no programmed consequence, followed by 15-min of milk presentation under the FR10 schedule.

The twenty-four mice were divided into three groups of eight. Each group was assigned a different training dose: 0.56, 1, or 1.78 mg/kg nicotine base. For the low (0.56 mg/kg) and medium (1 mg/kg) doses, training began with each respective training dose. All injections (except mecamylamine, which was i.p.) were given subcutaneously. The dose of 1.78 mg/kg initially disrupted responding during training sessions. Therefore, the dose of nicotine base was decreased to 1 mg/kg and increased over 8 nicotine training sessions to 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, and finally 1.78 mg/kg. Training was conducted by administering saline or nicotine s.c. in the first min of the session i.e., 10 min before milk was available, according to Gommans et al. (2000). The correct hole was determined by administration of saline or nicotine; nicotine- and saline-associated holes were right and left, respectively, for twelve mice and the assignment was reversed for the other twelve mice. These assignments remained the same for an individual throughout the study. Before the test criteria were satisfied, the order of training was predominantly two consecutive days for one condition followed by two consecutive days for the other condition (e.g. saline, saline, nicotine, nicotine); occasionally the training sequence alternated daily (e.g. saline, nicotine, saline) for 3–4 days non-systematically.

Discrimination testing

The first test was conducted when, for five consecutive or six out of seven training sessions, at least 80% of the total responses occurred on the correct hole and fewer than ten responses occurred on the incorrect hole prior to delivery of the first reinforcer of the session. Further tests were conducted when performance during 3 consecutive training sessions, including one saline and one nicotine training session, satisfied the test criteria. Test sessions were identical to training sessions except that ten responses in either hole resulted in access to milk. Moreover, in addition to saline or the training doses of nicotine, another dose of nicotine or another drug, alone or in combination, were administered during tests.

The first tests were with doses of nicotine necessary to generate a nicotine dose-response function. After establishing the nicotine dose-response function, dose-response functions for varenicline, cytisine, midazolam, and morphine were determined. A dose-response curve for a particular drug was determined in consecutive tests before initiating tests with another drug. The order of testing among drugs varied per mouse. Thereafter, tests were conducted with drugs in combination. Mecamylamine was administered 5 min before the session and nicotine, varenicline, and cytisine at the beginning of the session, as described previously (Cunningham and McMahon 2011). DHβE was administered immediately before nicotine, varenicline, or cytisine. Cytisine and varenicline also were administered immediately before nicotine. The final tests of this study included re-determinations of the dose-response functions for nicotine, varenicline, and cytisine. For all dose-effect tests, drugs were administered from ineffective doses up to doses that produced nicotine-appropriate responding, attenuated nicotine-appropriate responding, or decreased response rate to less than 20% of control for an individual mouse. The exception was DHβE, which was studied up to 3.2 mg/kg and not larger doses due to toxicity. Some drug combination tests (i.e. DHβE in combination with cytisine and varenicline; nicotine in combination with varenicline and cytisine) were only conducted in mice discriminating the large training dose (1.78 mg/kg) because mice discriminating the small training dose (0.56 mg/kg) satisfied the test criteria less frequently than the other groups.

Drugs

Mecamylamine was administered i.p. and all other drugs were administered s.c. in a volume equivalent to 10 ml/kg. Doses were expressed as the weight of the forms listed below, with the exception of nicotine dose, which was expressed as the weight of the base. Nicotine hydrogen tartrate salt (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), mecamylamine hydrochloride, varenicline dihydrochloride, morphine sulfate (National Institute on Drug Abuse, Rockville, MD), cytisine (Atomole Scientific, Hubei, China), midazolam hydrochloride (Bedford Laboratories, Bedford, OH), and dihydro-β-erythroidine hydrobromide (Tocris, St. Louis, MO) were dissolved in physiological saline.

Data analyses

Discrimination and response-rate data were expressed as a mean ± S.E.M. per training-dose condition. During the course of the study some mice died from sickness and drug overdose, which yielded a final sample size of 6–8 mice per training dose. Discrimination data were expressed as a percentage of nicotine-appropriate responses out of the total number of vehicle- and nicotine-appropriate responses. Response rate was expressed as the mean percentage of control. Control rate of responding (responses per s when milk was available under the FR10 schedule excluding responses during the 10-s period of milk availability) was calculated as the average rate for the preceding 5 non-drug (i.e. saline) sessions. Response rate was expressed and analyzed as a percentage of the control for individual mice. When response rate during a test was less than 20% of the control per individual for half or more of the animals, discrimination data for those animals were not plotted or analyzed, unless otherwise specified. However, all response rate data were included in the figures and analysis.

Straight lines were fitted to individual dose-effect data by means of GraphPad Prism version 5.0 for Windows (San Diego, CA). Lines were fitted to the linear portion of dose-effect curves, defined by doses producing 20 to 80% of the maximum effect, including not more than one dose producing less than 20% of the maximum effect and not more than one dose producing more than 80% of the maximum effect. Other doses were excluded. Linear regression was used to fit lines through dose-effect data and the lines from different functions were compared with an F-ratio test. A significant F-ratio value indicated that the data could not be fitted with a single line, i.e. there was a significant difference in slope. If the slopes were not significantly different, then parallel line analysis of data from individual subjects with the common, best-fitting slope was used to calculate the ED50 value, dose ratios, and their 95% confidence limits (Kenakin 1997; Tallarida 2000). ED50 values were considered significantly different when the 95% confidence limits of the dose ratio did not include 1. When an ED50 value could not be calculated from one of two lines being compared, a significant difference in potency was evidenced by a significant difference in slope. Rate of responding was considered unchanged by a drug if the slope of the dose-effect function was not significantly different from 0. Sessions to test criteria and the effects of single doses of drug were compared with paired t-test or repeated measures one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey or Dunnett’s post hoc tests (p<0.05).

To examine the nature of the interaction between nicotine, varenicline, and cytisine for producing discriminative stimulus effects, the ED50 values and 95% confidence limits of the individual drugs were plotted on isobolograms to show the line of additivity and error variance. The ED50 value and 95% confidence limits of nicotine determined in the presence of a dose of varenicline or cytisine was plotted and compared to the line of additivity.

RESULTS

Discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine as a function of training dose

For each training dose of nicotine, all mice passed the criteria for testing. The mean number of training sessions (including both drug and saline training) for mice to satisfy the test criteria was 90 sessions for the low training dose (0.56 mg/kg), 62 sessions for the medium training dose (1 mg/kg), and 58 sessions for the high training dose (1.78 mg.kg). ANOVA indicated a significant difference in number of days to satisfy the test criteria between the low and high training doses (F2,23=3.51, p<0.05).

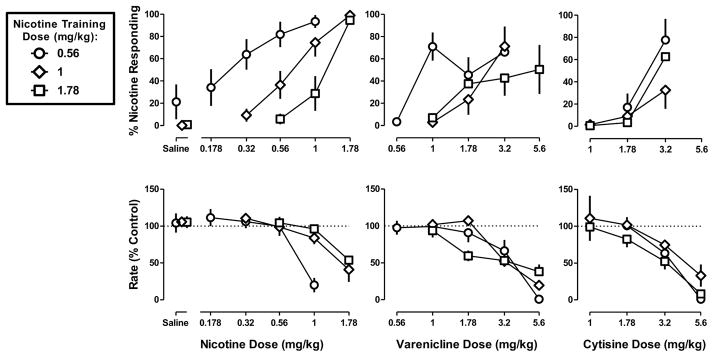

The dose-effect function for nicotine was determined at the beginning of the study and again at the end. The slopes and ED50 values of the two nicotine dose-effect determinations were not statistically different from each other and were averaged per individual for further analysis. Nicotine dose-dependently increased drug-appropriate responses for all three training doses (Figure 1 top left), whereas saline produced relatively low levels of nicotine-appropriate responses. When comparing the nicotine dose-response functions across the three training-dose conditions, there was a trend for an increased slope as training dose increased (F2,71=3.03, p=0.06). The ED50 values (95% confidence limits) of nicotine to produce discriminative stimulus effects were 0.28 (0.21–0.38), 0.67 (0.51–0.87), and 1.1 (0.82–1.5) mg/kg for the low-, medium-, and high-dose discriminations, respectively (Table 1). The ED50 value of nicotine to produce nicotine-hole responding was related to the training dose, i.e. smaller in the low-dose discrimination than in the medium-dose discrimination and, in turn, smaller in the medium-dose discrimination than in the high-dose discrimination.

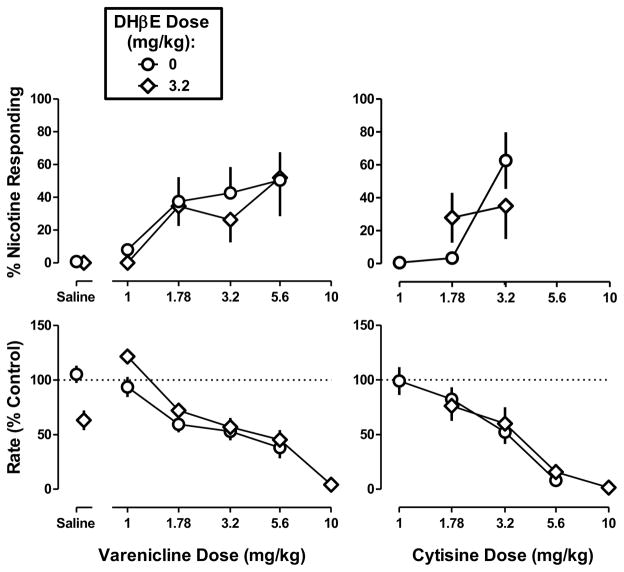

Figure 1. Discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine (left), varenicline (middle), and cytisine (right) in C57BL/6J mice discriminating one of three doses of nicotine base (0.56, 1, and 1.78 mg/kg).

Abscissae: Saline or dose in mg/kg body weight administered s.c. Ordinates: mean (± S.E.M.) percentage of responding on the nicotine nose-poke hole (top) and mean (± S.E.M.) rate of responding expressed as a percentage of control (bottom). Each discrimination symbol is averaged from every animal (7–8) tested except 1 mg/kg nicotine (4/8), 3.2 mg/kg varenicline (6/8), and 3.2 mg/kg cytisine (5/7) at the smallest training dose (0.56 mg/kg), 1.78 mg/kg nicotine (4/8) at the intermediate training dose (1 mg/kg), and 5.6 mg/kg varenicline (6/8) and 3.2 mg/kg cytisine (7/8) at the largest training dose (1 .78 mg/kg).

Table 1.

Maximum % drug-appropriate responding and ED50 values in separate groups of mice discriminating 0.56, 1, or 1.78 mg/kg of nicotine base. Potency ratios are calculated versus the ED50 value in mice discriminating 0.56 mg/kg of nicotine. Values in parentheses are 95% confidence limits.

| % Drug-appropriate responding | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Training dose in mg/kg | Maximum | ED50 in mg/kg | Potency ratio vs. 0.56 mg/kg training dose |

| Test drug: nicotine | |||

| 0.56 | 93% | 0.28 (0.21–0.38) | |

| 1 | 99% | 0.67 (0.51–0.87) | 2.4 (1.7–3.7)* |

| 1.78 | 94% | 1.1 (0.82–1.5) | 4.0 (2.7–6.4)** |

| Test drug: varenicline | |||

| 0.56 | 66% | 1.2 (0.68–2.0) | |

| 1 | 71% | 3.0 (1.4–6.6) | 2.6 (1.1–25)* |

| 1.78 | 50% | 3.8 (2.1–7.0) | 3.2 (1.6–11)* |

| Test drug: cytisine | |||

| 0.56 | 77% | 2.4 (1.9–3.1) | |

| 1 | 33% | n/a | |

| 1.78 | 63% | 2.8 (2.3–3.5) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) |

| Test drug: midazolam | |||

| 0.56 | 83% | 0.70 (0.30–1.6) | |

| 1 | 42% | n/a | |

| 1.78 | 17% | n/a | |

| Test drug: morphine | |||

| 0.56 | 15% | n/a | |

| 1 | 53% | 0.88 (0.28–2.78) | |

| 1.78 | 6% | n/a | |

| Response rate | ||

|---|---|---|

| Training dose in mg/kg | ED50 in mg/kg | Potency ratio vs. 0.56 mg/kg training dose |

| Test drug: nicotine | ||

| 0.56 | 1.1 (0.58–1.9) | |

| 1 | 1.7 (1.1–2.5) | 1.5 (1.1–2.6)* |

| 1.78 | n/s | n/a |

| Test drug: varenicline | ||

| 0.56 | 4.1 (2.9–5.9) | |

| 1 | 3.5 (2.2–5.7) | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) |

| 1.78 | 3.2 (2.5–4.2) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) |

| Test drug: cytisine | ||

| 0.56 | 3.4 (2.8–4.2) | |

| 1 | 4.2 (3.4–5.2) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) |

| 1.78 | 3.1 (2.6–3.6) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) |

| Test drug: midazolam | ||

| 0.56 | n/s | |

| 1 | n/s | n/a |

| 1.78 | 14 (3.6–52) | n/a |

| Test drug: morphine | ||

| 0.56 | 0.89 (0.51–1.5) | |

| 1 | 1.1 (0.63–1.9) | 1.2 (0.6–2.5) |

| 1.78 | 1.5 (1.0–2.3) | 1.7 (0.9–3.4) |

Significant difference in potency versus 0.56 mg/kg of nicotine training dose (p <0.05)

Significant difference in potency versus 0.56 and 1 mg/kg of nicotine training dose (p <0.05)

n/a; Not applicable; ED50 value not calculated

n/s; Not studied up to a dose that decreased responding to below 50% of control

The average (± S.E.M) control (saline) rate of responding in responses per s was 1.29 (± 0.24), 1.50 (± 0.19), and 1.98 (± 0.18) for the smallest, intermediate, and largest training doses of nicotine, respectively. The slopes of the dose-response functions for nicotine to decrease response rate were not significantly different from each other (F2,75=0.48, p=0.62) and there was a significant relationship between ED50 value and training dose (Figure 1 bottom left). The ED50 value of nicotine to decrease response rate in the low-dose condition (ED50=1.1 mg/kg) was significantly smaller than in the medium-dose discrimination (ED50=1.7 mg/kg) and high-dose discrimination (Table 1).

Discriminative stimulus effects of varenicline and cytisine

The dose-response functions of varenicline and cytisine to produce discriminative stimulus and rate-decreasing effects determined at the beginning and end of the study were not significantly different from each other and, therefore, were averaged in each mouse separately for each training-dose condition for further analysis. Varenicline and cytisine both dose-dependently increased nicotine-appropriate responding in each discrimination group (Figure 1 top center and right, respectively). When examining individual performance, greater than 80% of nicotine-appropriate responding was obtained in the small, medium, and large training-dose conditions for at least one dose of varenicline in 7/8, 6/7, and 5/8 mice, respectively, and one dose of cytisine in 5/8, 2/7, and 4/8 mice, respectively. However, mean performance after varenicline and cytisine never reached the same maximum as that obtained with nicotine at any training dose (Table 1). In mice discriminating the smallest dose (0.56), the percentage of nicotine-appropriate responses relative to saline was significantly greater after 5.6 mg/kg of cytisine (F2,17=5.48, p<0.05) and 1 mg/kg of varenicline (F4,33=5.11, p<0.05). ANOVA indicated that the maximum effect was not significantly different between training-dose conditions for varenicline (F2,18=0.29, p=0.75) and cytisine (F2,18=1.64, p=0.23). Varenicline was more potent in the low-dose discrimination than in the medium- and high-dose discriminations (Table 1). However, the ED50 value of varenicline did not differ in the medium- and high-dose discriminations; the dose ratio (95% confidence limits) was 1.3 (0.5–3.2) mg/kg. The ED50 value of cytisine also did not vary per training-dose condition. Moreover, unlike nicotine, the ED50 values of varenicline and cytisine to decrease response rate did not significantly differ as a function of training dose (Figure 1 bottom center and right, respectively) (Table 1).

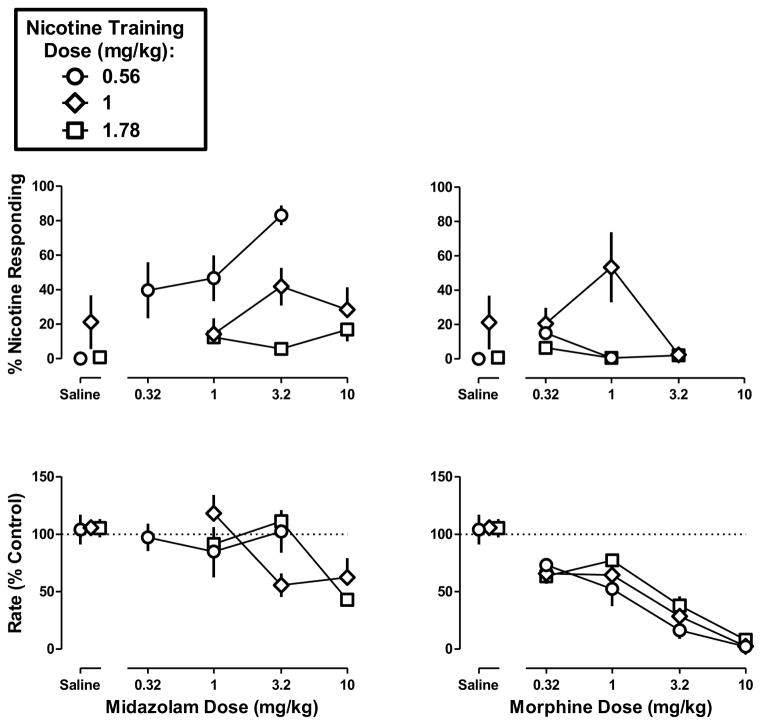

Effects of midazolam and morphine

Midazolam (0.32–10 mg/kg) produced a maximum of 83% nicotine-appropriate responses, in mice discriminating the smallest training dose (0.56 mg/kg) of nicotine (Figure 2 top left) and lower percentages of nicotine-appropriate responding at the larger training doses (Table 1). ANOVA indicated that midazolam produced significantly greater levels of nicotine-appropriate responding in the low-dose training group than the high-dose training group (F2,8= 6.04, p<0.05). Midazolam (up to 3.2 mg/kg) did not significantly alter response rate in the low-dose discrimination (F1,22=0.04, p=0.84); however, a larger dose (10 mg/kg) significantly decreased response rate to 62% and 43% of control for the medium- and high-dose discriminations, respectively (Figure 2 bottom left). Morphine (0.32–10 mg/kg) produced relatively low percentages of nicotine-appropriate responses at every training dose (Figure 2 top right). Morphine dose-dependently decreased response rate and the ED50 values were not significantly different from each other for all three training doses (Figure 2 bottom right) (Table 1).

Figure 2. Discriminative stimulus effects of midazolam (left) and morphine (right) in C57BL/6J mice discriminating one of three doses of nicotine base (0.56, 1, and 1.78 mg/kg).

Abscissae: Saline or dose in mg/kg body weight administered s.c. Ordinates: mean (± S.E.M.) percentage of responding on the nicotine nose-poke hole (top) and mean (± S.E.M.) rate of responding expressed as a percentage of control (bottom). Data above Saline are re-plotted from Figure 1. Each discrimination symbol is averaged from every animal (6–7) tested except 1 mg/kg morphine (5/7) at the smallest training dose (0.56 mg/kg), 3.2 mg/kg morphine (3/6) at the intermediate training dose (1 mg/kg), and 3.2 mg/kg morphine (5/6) at the largest training dose (1 .78 mg/kg).

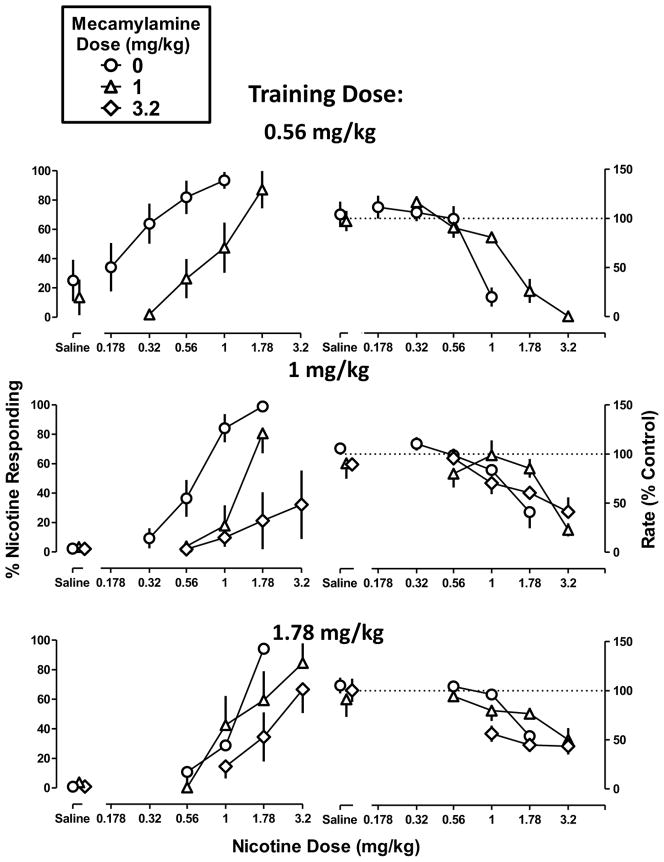

The effects of mecamylamine and DHβE in combination with nicotine

Mecamylamine (1 and 3.2 mg/kg) produced a maximum of 14% nicotine-appropriate responses (Figure 3 left, Saline), i.e., did not substitute for nicotine at any training dose, nor did mecamylamine significantly modify response rate. The smaller dose (1 mg/kg) of mecamylamine produced a significant rightward shift in the nicotine dose-effect functions in the low- and medium-dose discriminations but not in the high-dose discrimination (Figure 3 left; compare differences between circles and triangles from top to bottom) (Table 2). When a larger dose (3.2 mg/kg) of mecamylamine was combined with nicotine in the medium- and high-dose discriminations, there was significant antagonism in both cases. In the medium-dose discrimination, the slopes of the dose-effect functions for nicotine alone versus nicotine in combination with mecamylamine (3.2 mg/kg) were significantly different. The same functions in the high-dose discrimination shared a common slope; the magnitude of rightward shift was 2.3 (1.5–4.1) (Table 2). The dose-effect function of nicotine to decrease response rate was not significantly modified by mecamylamine, although there was a non-significant trend for 1 mg/kg of mecamylamine to produce antagonism in the low- and medium-dose discriminations (Figure 3 right) (Table 2).

Figure 3. Discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine in combination with mecamylamine in C57BL/6J mice discriminating nicotine base at doses of 0.56 mg/kg (top), 1 mg/kg (middle), and 1.78 mg/kg (bottom).

Abscissae: Saline or dose of nicotine base in mg/kg body weight administered s.c. Ordinates: mean (± S.E.M.) percentage of responding on the nicotine nose-poke hole (left) and mean (± S.E.M.) rate of responding expressed as a percentage of control (right). Dose-response curves for nicotine alone are re-plotted and the number of animals composing each point is identical to Figure 1. Each discrimination symbol is averaged from every animal tested except 1 mg/kg mecamylamine + 3.2 mg/kg nicotine (4/8) at the smallest training dose (0.56 mg/kg), 3.2 mg/kg mecamylamine + 3.2 mg/kg nicotine (5/8) at the intermediate training dose (1 mg/kg), and 3.2 mg/kg mecamylamine + 1.78 and 3.2 mg/kg nicotine (4/8 in both cases) at the largest training dose (1 .78 mg/kg).

Table 2.

ED50 values for nicotine alone and in combination with antagonist in in separate groups of mice discriminating 0.56, 1, or 1.78 mg/kg of nicotine base. Values in parentheses are 95% confidence limits.

| % Drug-appropriate responding | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine training dose (mg/kg) | ||||||

| 0.56 | 1 | 1.78 | ||||

| Drug(s) | ED50 value | Potency ratio | ED50 value | Potency ratio | ED50 value | Potency ratio |

| Nicotine alone | 0.24 (0.13–0.41) | 0.67 (0.52–0.87) | 1.1 (0.83–1.5) | |||

| + mecamylamine (1 mg/kg) | 0.99 (0.55–1.8) | 4.1 (2.1–17)* | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 2.1 (1.4–3.0)* | 1.4 (0.93–2.0) | 1.3 (0.7–2.1) |

| + mecamylamine (3.2 mg/kg) | n/t | n/t | n/c | n/a | 2.5 (1.6–3.7) | 2.3 (1.5–4.1)* |

| + DHβE (3.2 mg/kg) | 0.63 (0.27–1.5) | 2.6 (1.1–15)* | 0.70 (0.39–1.2) | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | n/c | n/a |

| Response rate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine training dose (mg/kg) | ||||||

| 0.56 | 1 | 1.78 | ||||

| Drug(s) | ED50 value | Potency ratio | ED50 value | Potency ratio | ED50 value | Potency ratio |

| Nicotine alone | 1.1 (0.57–2.0) | 2.1 (1.2–3.6) | n/c | |||

| + mecamylamine (1 mg/kg) | 1.3 (0.97–1.8) | 1.2 (0.4–2.0) | 3.3 (1.5–7.2) | 1.6 (0.7–2.7) | n/c | n/a |

| + mecamylamine (3.2 mg/kg) | n/t | n/t | 2.2 (1.3–3.6) | 1.1 (0.5–1.7) | 1.5 (0.64–3.5) | n/a |

| + DHβE (3.2 mg/kg) | 0.71 (0.57–0.89) | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | 1.8 (1.3–2.6) | 0.9 (0.5–1.3) | 0.91 (0.17–4.9) | n/a |

Significant difference in potency versus nicotine alone (p<0.05)

n/t; Not tested

n/c; ED50 value not calculated because responding not decreased to below 50% control

n/a; Not applicable

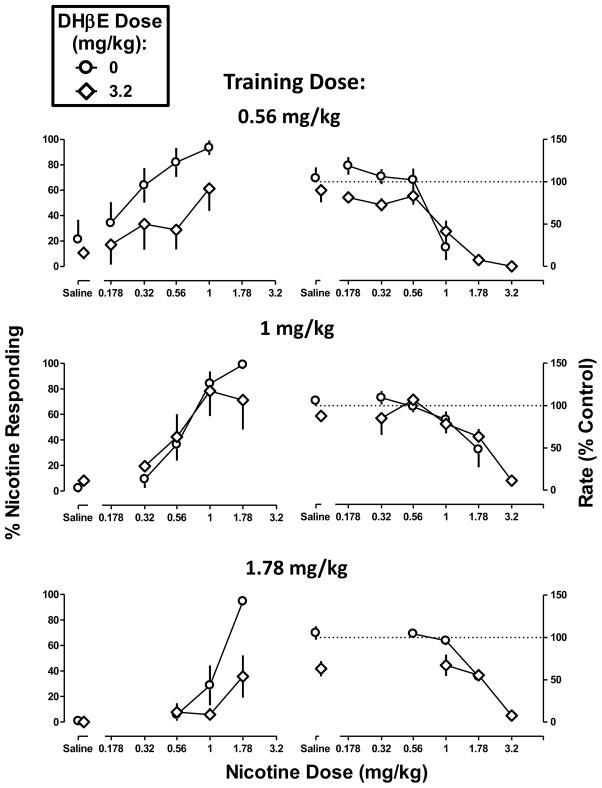

DHβE (3.2 mg/kg) produced a maximum of 11% nicotine-appropriate responses, i.e., did not substitute for the nicotine discriminative stimulus at any training dose (Figure 4 left, saline). DHβE (3.2 mg/kg) decreased response rate in mice discriminating the high dose (t=3.54, p<0.01) but not the low and medium training doses. When combined with nicotine, DHβE (3.2 mg/kg) produced a rightward shift of the nicotine dose-response curve in the low-dose discrimination (Table 1) but was ineffective in the medium-dose discrimination (Figure 4 left top and middle, respectively). DHβE (3.2 mg/kg) attenuated the effects of the training dose (1.78 mg/kg) of nicotine in mice discriminating the high dose; however, the magnitude of shift in the nicotine dose-response function could not be calculated because nicotine did not produce greater than 50% nicotine-appropriate responding up to a dose that significantly decreased response rate and the two functions did not share a slope (F1,44 = 8.45, p<0.01). DHβE (3.2 mg/kg) did not significantly modify the rate-decreasing effects of nicotine (Figure 4 right) (Table 2).

Figure 4. Discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine in combination with dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE) in C57BL/6J mice discriminating nicotine base at doses of 0.56 mg/kg (top), 1 mg/kg (middle), and 1.78 mg/kg (bottom).

Abscissae: Saline or dose of nicotine base in mg/kg body weight administered s.c. Ordinates: mean (± S.E.M.) percentage of responding on the nicotine nose-poke hole (left) and mean (± S.E.M.) rate of responding expressed as a percentage of control (right). Dose-response curves for nicotine alone are re-plotted and the number of animals composing each point is identical to Figure 1. Each discrimination symbol is averaged from every animal tested except 3.2 mg/kg DHβE + 1 mg/kg nicotine (5/8) at the smallest training dose (0.56 mg/kg) and 3.2 mg/kg DHβE + 1.78 mg/kg nicotine (4/8) at the largest training dose (1 .78 mg/kg).

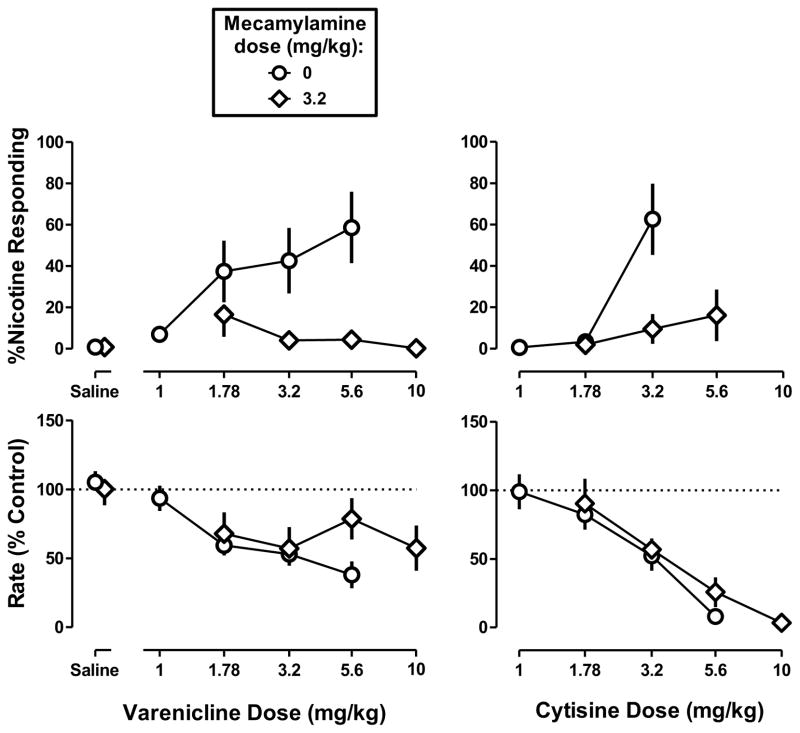

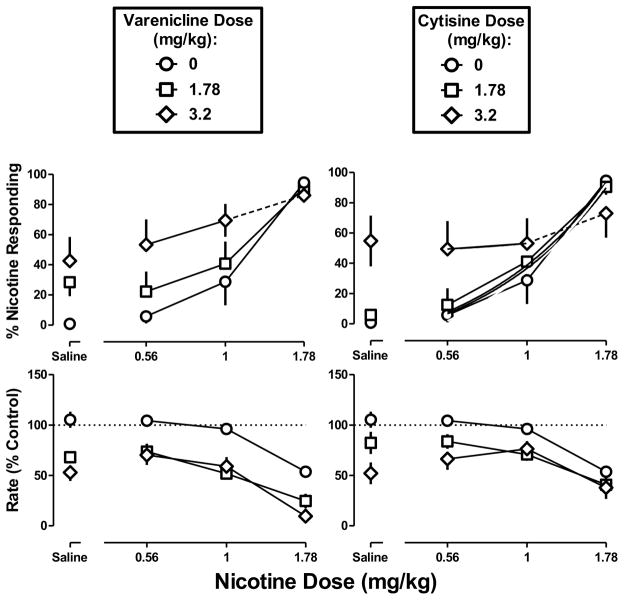

Effects of mecamylamine and DHβE in combination with varenicline and cytisine

In mice discriminating 1.78 mg/kg of nicotine, mecamylamine (3.2 mg/kg) produced downward shifts in the dose-response curves for varenicline and cytisine (Figure 5 top left and right, respectively). Mecamylamine decreased the percentage of nicotine-appropriate responses up to doses of varenicline and cytisine that markedly decreased rate of responding; a dose of varenicline larger than 10 mg/kg was lethal. Mecamylamine significantly antagonized the rate-decreasing effects of varenicline (F2,52=3.71, p<0.05) but did not antagonize the rate-decreasing effects of cytisine (Figure 5 bottom). DHβE (3.2 mg/kg) did not significantly modify the discriminative stimulus or rate-decreasing effects of varenicline or cytisine up to doses that eliminated responding (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Discriminative stimulus effects of varenicline (left) and cytisine (right) in combination with mecamylamine in C57BL/6J mice discriminating 1.78 mg/kg of nicotine base.

Abscissae: Saline or dose in mg/kg body weight administered s.c. Ordinates: mean (± S.E.M.) percentage of responding on the nicotine nose-poke hole (top) and mean (± S.E.M.) rate of responding expressed as a percentage of control (bottom). Each discrimination symbol is averaged from every animal (6–8) tested except 3.2 mg/kg cytisine alone (7/8), 3.2 mg/kg mecamylamine + 10 mg/kg varenicline (4/6), and 3.2 mg/kg mecamylamine + 5.6 mg/kg cytisine (3/6).

Figure 6. Discriminative stimulus effects of varenicline (left) and cytisine (right) in combination with DHβE in C57BL/6J mice discriminating 1.78 mg/kg of nicotine base.

Abscissae: Saline or dose in mg/kg body weight administered s.c. Ordinates: mean (± S.E.M.) percentage of responding on the nicotine nose-poke hole (top) and mean (± S.E.M.) rate of responding expressed as a percentage of control (bottom). Each discrimination symbol is averaged from every animal (6–8) tested except 3.2 mg/kg cytisine alone (7/8) and 3.2 mg/kg DHβE + 3.2 mg/kg cytisine (5/6).

Effects of varenicline and cytisine in combination with nicotine

Varenicline at doses of 1.78 and 3.2 mg/kg produced 28% and 43% nicotine-appropriate responding, respectively, and decreased response rate to 68% and 53% of control, respectively (Figure 7 left, Saline). The smaller dose (1.78 mg/kg) of varenicline did not significantly modify the nicotine dose-effect function for discriminative stimulus effects, i.e. the ED50 value (95% confidence limits) of 0.99 (0.72–1.5) mg/kg for nicotine determined in the presence of varenicline (1.78 mg/kg) was not significantly different from the nicotine control. The larger dose (3.2 mg/kg) of varenicline produced a leftward shift in the nicotine dose-effect function (Figure 7 top left, diamonds), as evidenced by a significant difference in intercept with respect to the nicotine control (p<0.05). However, the shift was due to the relatively high percentage of nicotine-appropriate responding produced by varenicline alone. Varenicline also produced a leftward shift in the effects of nicotine to decrease response rate (Figure 7 bottom left). Cytisine at doses of 1.78 and 3.2 mg/kg produced 6% and 55% nicotine-appropriate responding and decreased response rate to 82% and 52% of control, respectively (Figure 7 right, Saline). The smaller dose (1.78 mg/kg) of cytisine did not alter the nicotine dose-response function (F2,43=0.72, p>0.05), whereas the larger dose of cytisine produced a change in the slope of the nicotine dose-response function (F1,35=4.61, p<0.05), evidenced by a much shallower slope as compared with the control curve.

Figure 7. Discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine in combination with varenicline (left) or cytisine (right) in C57BL/6J mice discriminating 1.78 mg/kg of nicotine base.

Abscissae: Saline or dose of nicotine base in mg/kg body weight administered s.c. Ordinates: mean (± S.E.M.) percentage of responding on the nicotine nose-poke hole (top) and mean (± S.E.M.) rate of responding expressed as a percentage of control (bottom). Symbols connected with dotted lines are discrimination data from all animals, including those responding less than 20% of the control response rate. Each discrimination symbol is averaged from every animal tested except 1.78 mg/kg varenicline + 1.78 mg/kg nicotine (5/8), 3.2 mg/kg varenicline + 1 mg/kg nicotine (7/8), and 1.78 mg/kg cytisine + 1.78 mg/kg nicotine (7/8).

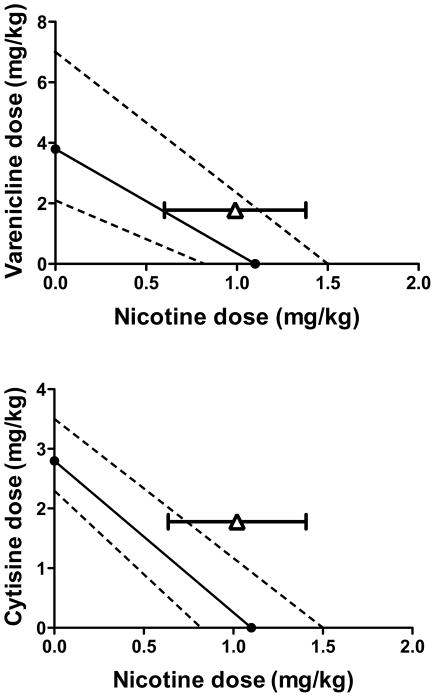

Isobolographic analysis of discriminative stimulus effects at the 50% effect level demonstrated that the combined effects of cytisine (1.78 mg/kg) and nicotine were less than additive (i.e. antagonistic), as evidenced by the ED50 value of nicotine in the presence of cytisine being outside the 95% confidence of the line of additivity (Figure 8). In contrast, the ED50 value of nicotine determined in the presence of varenicline (1.78 mg/kg) was within the 95% confidence limits of the line of additivity.

Figure 8. Isobolograms showing the line of additivity for the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine in combination with varenicline (top) or cytisine (bottom).

Abscissae: Dose of nicotine base in mg/kg body weight administered s.c. Ordinates: Dose of varenicline (top) and cytisine (bottom) in mg/kg body weight administered s.c. The dotted lines connect the respective upper and lower 95% confidence limits of the ED50 values. The triangles and lines extending from the triangles are the ED50 values and 95% confidence limits of nicotine determined in the presence of 1.78 mg/kg of varenicline (top) and 1.78 mg/kg of cytisine (bottom).

DISCUSSION

Separate groups of mice were trained to discriminate a dose (0.56, 1, or 1.78 mg/kg) of nicotine base from saline. As training dose increased, the slopes of the dose-effect functions and ED50 values of nicotine to produce drug-appropriate responding also increased, consistent with previous studies with other classes of training drug (Colpaert et al. 1980). Varenicline and cytisine did not fully substitute for the nicotine discriminative stimulus, consistent with varenicline and cytisine having lower agonist efficacy than nicotine. However, as compared with nicotine, the slopes of dose-effect functions and ED50 values for both varenicline and cytisine did not always vary with the training dose of nicotine, thereby resulting a difference in relative potency among the drugs as a function of training dose. These results are indicative of overlapping, yet distinct, pharmacologic mechanism(s) among the drugs, including a difference in selectivity for multiple receptor subtypes.

As described in Colpaert et al. (1980) for μ opioid agonists, the current results demonstrate that the position of the dose-effect function for the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine varies as a function of training dose. The smallest doses of nicotine producing the maximum effect generally were the training doses, although a larger dose was needed in some mice at the smallest and intermediate training doses. Ineffective doses of nicotine were one-half log unit smaller than the intermediate (1 mg/kg) and largest training doses (1.78 mg/kg), whereas ineffective doses were as much as a full log unit smaller than the smallest training dose (0.56 mg/kg), thereby resulting in a difference in slope. In addition, ED50 value increased positively with training dose, as reported previously (Smith and Stolerman 2009).

Multiple doses of nicotine have been trained using the same methods (Stolerman et al., 1999); however, multiple training doses of nicotine have not been used extensively to compare receptor mechanisms of multiple test drugs. The current study compared the effects of nicotine, varenicline, cytisine, midazolam, and morphine across a broad range of nicotine training doses. One advantage of this approach is its sensitivity to differences in agonist efficacy, as demonstrated elsewhere for μ opioids (Young et al. 1992). Another advantage is the breadth of information provided by the multiple dose-effect functions of the training drug established at the different training doses, which can vary in slope and position along the dose axis (Colpaert et al. 1980). To the extent that drugs produce their effects through the same mechanism, dose-effect functions should vary in the same way as a function of training dose for both the training drug and test drugs. Here, there was no clear relationship between nicotine training dose and either the maximum effect or position of the dose-effect gradient for varenicline and cytisine. Partial substitution of varenicline and cytisine is therefore not readily accounted for by only a difference in agonist efficacy at a particular subtype of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. The absence of an orderly relationship between training dose and the effects of varenicline and cytisine strongly suggests that nicotine, varenicline, and cytisine differ in their selectivity for multiple subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (Grady et al 2010).

Varenicline and cytisine did not produce the same high level of nicotine-appropriate responding as that obtained with nicotine at any training dose. If the partial effect is due to low efficacy, such as that reported at α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (Coe et al. 2005), then receptor theory predicts that the low efficacy agonist attenuates the effects of the higher efficacy agonist (Kenakin 2009). Support for this prediction is evidenced by antagonism of the effects of nicotine on dopamine turnover as described (Coe et al. 2005). Cytisine attenuated the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine in mice discriminating the largest training dose (1.78 mg/kg) of nicotine, as evidenced by sub-additivity and attenuation of the effects of the training dose of nicotine. Similar results with cytisine have been obtained in rats (Reavill et al. 1990; Jutkiewicz et al. 2011), whereas varenicline and nicotine had additive discriminative stimulus effects in the current study. Cytisine is reported to have lower agonist efficacy than varenicline in vitro (Coe et al. 2005), and this difference in efficacy might be the difference between antagonism on the one hand (cytisine) and agonism on the other (varenicline). The current results suggest that partial substitution of cytisine for nicotine does not depend on training dose, at least under some conditions. Full substitution of cytisine for nicotine is accompanied by marked decreases in operant response rate (Jutkiewicz et al. 2011), suggesting that the disruptive effects of cytisine are a critical determinant of the level of substitution. Under conditions that are more resistant to drug-induced disruption, e.g. responding for stimulus-shock termination, cytisine produces high levels of nicotine-appropriate responding (Cunningham et al. 2012).

A drug discrimination test assesses the extent to which a test drug shares effects with the training drug, and at least one non-nicotinic drug appeared to share effects with a relatively small dose of nicotine. The benzodiazepine midazolam fully substituted for nicotine at the smallest training dose (0.56 mg/kg) and produced less substitution as the training dose was increased. The tendency for non-nicotinic drugs to substitute for the smallest training dose appears related to the difficulty that mice had in detecting this dose of nicotine as being different from saline. This was evidenced during both training and test sessions. The number of training sessions required to satisfy the test criteria was significantly greater at the smallest training dose as compared with the larger training doses. After the test criteria had been satisfied, the number of training sessions required to satisfy the criteria for subsequent testing was greatest at the smallest training dose, thereby resulting in one-third the number of tests overall as compared with the larger training doses of nicotine. The smallest training dose was associated with the greatest number of nicotine-appropriate responses during tests with saline and the greatest number of saline-appropriate responses during tests with the training dose, thereby resulting in the dose-response gradient with a shallow slope. That 0.56 mg/kg of nicotine base is near the smallest dose that can be discriminated is evidenced by a previous study showing that C57BL/6J mice were less accurate in their discrimination of 0.4 mg/kg as compared with 0.8 or 1.6 mg/kg (Stolerman et al. 1999), although discrimination of 0.4 mg/kg has been reported in multiple studies (Varvel et al. 1999; Shoaib et al. 2002). The discrimination of 0.56 mg/kg of nicotine base was somewhat selective inasmuch as morphine did not substitute for nicotine at any training dose. The current results, in conjunction with previous studies (Mariathasan and Stolerman 1993; Cunningham et al. 2012), suggest that the interaction between nicotine and midazolam is to some extent pharmacologically selective and evident under a variety of experimental conditions.

The competitive β-subunit containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist DHβE (Chavez-Noriega et al. 1997) produced a 2.6-fold rightward shift in the nicotine dose-response function for discriminative stimulus effects in mice discriminating the smallest training dose (0.56 mg/kg), as has been described previously albeit with a larger training dose of nicotine (Gommans et al. 2000). In contrast, DHβE produced little or no antagonism of nicotine, varenicline, and cytisine at the largest training dose (1.78 mg/kg). The smallest training dose therefore appears most sensitive to β-subunit containing receptor agonism as well as to the actions of non-nicotinics (midazolam). The current study, in conjunction with a previous study in transgenic mice lacking receptors containing β subunits (Shoaib et al. 2002), strongly suggest that β subunits mediate the behavioral effects of small and not necessarily larger doses of nicotine. Mecamylamine fully antagonized the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine, varenicline, and cytisine, demonstrating involvement of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. The magnitude of antagonism of the discrimination was limited by the failure of mecamylamine to antagonize the rate-decreasing effects of relatively large doses of nicotine, thereby implicating different receptor mechanisms in mediating discrimination and effects on response rate. The potency of mecamylamine as an antagonist, or dose producing a given magnitude of rightward shift in the nicotine dose-effect function, decreased as the training dose of nicotine increased. Given that mecamylamine is a non-competitive antagonist (Varanda et al. 1985), differences in its potency cannot be attributed to different receptor mechanisms underlying the effects of nicotine, as is possible with a competitive antagonist (i.e. DHβE; Jutkiewicz et al. 2011). However, as was the case with mecamylamine, the magnitude of antagonism by DHβE was limited by disruption of the operant response at relatively large doses.

While the nicotine dose to which mice were trained was responsible for differences in the position of the nicotine dose-effect functions, other factors (e.g., repeated treatment) were most likely responsible for the relatively small, albeit significantly greater potency of nicotine to decrease response rate in mice discriminating the small training dose as compared with the mice discriminating the medium and large training. Tolerance to other in vivo effects of nicotine has been reported previously (Collins et al. 1988, Stolerman et al. 1973, Jackson et al. 2009). This apparent tolerance to the effects of nicotine on response rate was not accompanied by the same difference in sensitivity to varenicline, cytisine, and morphine as a function of training dose. Tolerance in the absence of cross-tolerance is further indicative of a difference in pharmacologic mechanism. In particular, this result is opposite to the prediction derived from receptor theory regarding loss of sensitivity to pharmacologically related agonists that differ in efficacy, i.e. tolerance/cross-tolerance is expected to be greater for low efficacy agonists as compared with higher efficacy agonists (Kenakin 2009). Given that varenicline and cytisine have been demonstrated to have lower agonist efficacy than nicotine at α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, this particular subtype does not appear to mediate the decreased rate of fixed ratio responding.

In summary, varenicline and cytisine did not fully substitute for nicotine across a range of training doses, there was little evidence of a systematic relationship between potency and maximum effect of varenicline and cytisine among training dose conditions, and the effects of nicotine were not antagonized by varenicline. Collectively, these results suggest that a difference in efficacy at one particular subtype of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is not sufficient to account for the qualitatively different effects of nicotine, varenicline, and cytisine. Instead, these nicotinic drugs appear to vary in their activity at multiple subtypes of receptor, and the extent to which these data are predictive of mechanisms underlying therapeutics remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND FUNDING

The authors are grateful to C. Rock, D. Schulze, and A. Zaki for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [DA25267].

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- DHβE

dihydro-β-erythroidine

References

- Chandler CJ, Stolerman IP. Discriminative stimulus properties of the nicotinic agonist cytisine. Psychopharmacology. 1997;129:257–264. doi: 10.1007/s002130050188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Noriega LE, Crona JH, Washburn MS, Urrutia A, Elliott KJ, Johnson EC. Pharmacological characterization of recombinant human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors h alpha2beta2, h alpha2beta4, h alphabeta2, h alpha3beta4, h alpha4beta2, h alpha4beta4 and h alpha7 expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:346–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe JW, Brooks PR, Vetelino MG, Wirtz MC, Arnold EP, Huang J, Sands SB, Davis TI, Lebel LA, Fox CB, Shrikhande A, Heym JH, Schaeffer E, Rollema H, Lu Y, Mansbach RS, Chambers LK, Rovetti CC, Schulz DW, Tingley FD, 3rd, O’Neill BT. Varenicline: an alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3474–3477. doi: 10.1021/jm050069n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AC, Romm E, Wehner JM. Nicotine tolerance: an analysis of the time course of its development and loss in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 1988;96:7–14. doi: 10.1007/BF02431526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpaert FC, Niemegeers CJ, Janssen PA. Factors regulating drug cue sensitivity: the effect of training dose in fentanyl-saline discrimination. Neuropharmacology. 1980;19:705–713. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(80)90061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft RM, Howard JL. Cue properties of oral and transdermal nicotine in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 1988;96:281–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00216050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CS, McMahon LR. The effects of nicotine, varenicline, and cytisine on schedule-controlled responding in mice: differences in α4β2 nicotinic receptor activation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;654:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CS, Javors M, McMahon LR. Pharmacologic characterization of a nicotine discriminative stimulus in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;341:840–849. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.193078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gommans J, Stolerman IP, Shoaib M. Antagonism of the discriminative and aversive stimulus properties of nicotine in C57BL/6J mice. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:2840–2847. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Guiducci S, Tedesco V, Corbioli S, Zanetti L, Moretti M, Zanardi A, Rimondini R, Mugnaini M, Clementi F, Chiamulera C, Zoli M. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the mesolimbic pathway: primary role of ventral tegmental area alpha6beta2* receptors in mediating systemic nicotine effects on dopamine release, locomotion, and reinforcement. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5311–5325. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5095-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SR, Drenan RM, Breining SR, Yohannes D, Wageman CR, Fedorov NB, McKinney S, Whiteaker P, Bencherif M, Lester HA, Marks MJ. Structural differences determine the relative selectivity of nicotinic compounds for native alpha 4 beta 2*-, alpha 6 beta 2*-, alpha 3 beta 4*- and alpha 7-nicotine acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:1054–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8. Institute for Laboratory Animal Research, Division of Earth and Life Sciences, National Research Council; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KJ, Walters CL, Miles MF, Martin BR, Damaj MI. Characterization of pharmacological and behavioral differences to nicotine in C57Bl/6 and DBA/2 mice. Neuropharmacology. 2009;57:347–355. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutkiewicz EM, Brooks EA, Kynaston AD, Rice KC, Woods JH. Patterns of nicotinic receptor antagonism: nicotine discrimination studies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339:194–202. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.182170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T. Pharmacologic Analysis of Drug-Receptor Interaction. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T. A pharmacology primer: theory, application and methods. Academic Press; San Diego, California: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- LeSage MG, Shelley D, Ross JT, Carroll FI, Corrigall WA. Effects of the nicotinic receptor partial agonists varenicline and cytisine on the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;91:461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariathasan EA, Stolerman IP. Overshadowing of nicotine discrimination in rats: a model for behavioural mechanisms of drug interactions? Behav Pharmacol. 1993;4:209–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalak KB, Carroll FI, Luetje CW. Varenicline is a partial agonist at alpha4beta2 and a full agonist at alpha7 neuronal nicotinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:801–805. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt JA, Stolerman IP, Garcha HS, Giardini V, Feyerabend C. Discriminative stimulus properties of nicotine: further evidence for mediation at a cholinergic receptor. Psychopharmacology. 1983;81:54–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00439274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavill C, Walther B, Stolerman IP, Testa B. Behavioural and pharmacokinetic studies on nicotine, cytisine and lobeline. Neuropharmacology. 1990;29:619–624. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(90)90022-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H, Chambers LK, Coe JW, Glowa J, Hurst RS, Lebel LA, Lu Y, Mansbach RS, Mather RJ, Rovetti CC, Sands SB, Schaeffer E, Schulz DW, Tingley FD, 3rd, Williams KE. Pharmacological profile of the alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline, an effective smoking cessation aid. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:985–994. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoaib M, Gommans J, Morley A, Stolerman IP, Grailhe R, Changeux JP. The role of nicotinic receptor beta-2 subunits in nicotine discrimination and conditioned taste aversion. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42:530–539. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JW, Mogg A, Tafi E, Peacey E, Pullar IA, Szekeres P, Tricklebank M. Ligands selective for alpha4beta2 but not alpha3beta4 or alpha7 nicotinic receptors generalise to the nicotine discriminative stimulus in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 2007;190:157–170. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JW, Stolerman IP. Recognising nicotine: the neurobiological basis of nicotine discrimination. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;192:295–333. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolerman IP, Fink R, Jarvik ME. Acute and chronic tolerance to nicotine measured by activity in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1973;30:329–342. doi: 10.1007/BF00429192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolerman IP, Naylor C, Elmer GI, Goldberg SR. Discrimination and self-administration of nicotine by inbred strains of mice. Psychopharmacology. 1999;141:297–306. doi: 10.1007/s002130050837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida RJ. Drug Synergism and Dose-Effect Data Analysis. Chapman Hall/CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Varanda WA, Aracava Y, Sherby SM, VanMeter WG, Eldefrawi ME, Albuquerque EX. The acetylcholine receptor of the neuromuscular junction recognizes mecamylamine as a noncompetitive antagonist. Mol Pharmacol. 1985;28:128–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varvel SA, James JR, Bowen S, Rosecrans JA, Karan LD. Discriminative stimulus (DS) properties of nicotine in the C57BL/6 mouse. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;63:27–32. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, Masaki MA, Geula C. Discriminative stimulus effects of morphine: effects of training dose on agonist and antagonist effects of mu opioids. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;261:246–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Walker EA, Sutherland J, 2nd, Young AM. Discriminative stimulus effects of two doses of fentanyl in rats: pharmacological selectivity and effect of training dose on agonist and antagonist effects of mu opioids. Psychopharmacology. 2000;148:136–145. doi: 10.1007/s002130050035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]