Abstract

Building on the conceptual framework of emotional security theory (EST) [1], this study longitudinally examined multiple factors linking parental depressive symptoms and child internalizing symptoms. Participants were 235 children (106 boys, 129 girls) and their cohabiting parents. Assessments included mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms when children were in kindergarten, parents’ negative expressiveness when children were in first grade, children’s emotional insecurity one year later, and children’s internalizing symptoms in kindergarten and second grade. Findings revealed both mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms were related to changes in children’s internalizing symptoms as a function of parents’ negative emotional expressiveness and children’s emotional insecurity. In addition to these similar pathways, distinctive pathways as a function of parental gender were identified. Contributions are considered for understanding relations between parental depressive symptoms and children’s development.

Keywords: Parental depressive symptoms, emotional security, parental negative emotional expressiveness, children’s internalizing symptoms

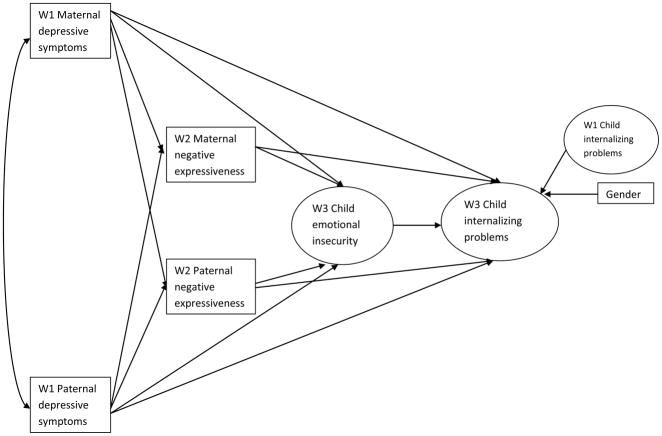

Children of depressed parents are two to five times more likely to develop disorders than children of nondepressed parents [2, 3], including internalizing problems (e.g., anxious/depressed symptoms) [4]. However, the heterogeneity of developmental pathways calls for explication of the processes that account for outcomes5. Even accounting for genetic factors, family environmental influences emerge in relations among paternal and maternal depressive symptoms and child internalizing problems [6, 7]. Regarding children’s socio-emotional adjustment, kindergarten and elementary school years are formative. However, relatively few studies have prospectively explored family mediators of links between parental depressive symptoms and children n’s internalizing problems. These questions are the focus of this study. The conceptual model for this study is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed mediational model of parental depressive symptoms, parental negative emotional expressiveness and children’s emotional insecurity in predicting children’s internalizing problems.

Mothers’ and Fathers’ Depressive Symptoms

The family provides a primary context to understand child functioning and adjustment, including the influence of both mothers and fathers in the development of their children [8]. However, attention in the literature on parental depression and child adjustment has mainly focused on maternal influence, with a relative lack of research about the role of fathers [9]. Additionally, few studies have examined both parents’ depressive symptoms in the context of children’s insecurity about parental relations and adjustment [10]. Recent research indicates that fathers’ and mothers’ depressive symptoms can impact child adjustment [11, 12]. Accordingly, the current study examines the impact of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms in the links between the parental depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing symptoms.

Negative Emotional Expressiveness

The role of parents’ negative emotional expressiveness in pathways between parental depressive symptoms and children’s risk for adjustment problems has been little examined but the evidence suggests it merits study [5, 13, 14]. Previous research has indicated that depressed parents are characterized by high negative affect or emotional expressiveness, including hostility and irritability [15, 16]. Given evidence for negative affect, communications, and appraisals in couples with a depressed spouse [17], we longitudinally examine how, or whether, each parent’s depressive symptoms affect their own and their spouse’s negative emotional expressiveness. Specifically, in this present study, the effects of parental depressive symptoms on children’s are hypothesized to be mediated, at least in part, by the parents’ negative emotional expressiveness, associated with their depressive symptoms, expressed in the family. Furthermore, parents’ negative emotional expressiveness is hypothesized to be related to children’s emotional insecurity [8, 18], thereby increasing their risk for internalizing symptoms [19] (see Figure 1). Emotional Security Theory

The role of parental negative emotional expressiveness on children’s emotional security and adjustment is implicated by research and theory [20–23]. In the present study, emotional insecurity is theorized as being associated with the development of internalizing problems in the context of parental depression [24]. Moreover, the negativity among depressed parents might be expected to dampen children’s emotional security. Children’s insecurity, in turn, is expected to predict their internalizing symptoms of withdrawal, somatic problems, and signs of depression or anxiety.

According to EST [1], children’s emotional security is related to their personal sense of protection and safety in various family settings. A useful analogy is to think about emotional security as a bridge between the child and the world; high index of security in the family, as indicated by a positive family environment, allows parents to serve as a secure base, supporting the child’s exploration and relationships with others. If a negative family environment erodes this ‘bridge’, children may lose confidence and become hesitant or uncertain how to move forward, unable to find appropriate footing within themselves, or in interactions with others.

An assumption of EST is that preserving a sense of security is a goal that organizes children’s responding, including emotional reactivity and action tendencies such as behavioral dysfunction, avoidance, and involvement in marital conflict [1, 25]. Emotional security thus reflects an organizational perspective on children’s regulatory processes [26], evident in these multiple types of responding, which has been shown to predict their later adjustment [27].

Secure base notions are at the foundation of both EST and attachment theory [28]. According to attachment theory, emotional bonds between parents and children are pertinent to children’s sense of security, particularly in times of stress. These notions are extended to include other family relations by EST, including interparental relations. EST thus calls attention to multiple family relationships in contributing to children’s emotional security, thereby broadening notions of emotional security as a function of multiple family processes.

Specifically, this study longitudinally examines the effects of parents’ negative emotional expressiveness associated with parental depressive symptoms on children’s emotional insecurity, and the role of this pathway in children’s development of internalizing problems. Multiple past studies have indicated links between emotional insecurity and children’s internalizing problems [19]; thus, there is considerable empirical basis for expecting this pathway in the model.

Theoretical Model

As shown in Figure 1, pathways are identified between parental depressive symptoms and child internalizing symptoms, with parental negative emotional expressiveness and child emotional insecurity acting as mediating variables. The stringency of this model test is increased by including autoregressive controls accounting for children’s initial levels of internalizing symptoms. Interactional models on relations between parental depression symptoms and child adjustment are also of interest. For example, parental depression may have stronger effects on present than future expressiveness and parental expressiveness may have greater effects on present than future emotional insecurity. However, the goal of this report was to advance a developmental model towards explaining prospective relations between parental depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing problems. That is, the purpose of the study was to examine the mechanisms or processes underlying the intergenerational transmission of internalizing problems.

Specifically, we hypothesize that (a) depressive symptoms of both mothers and fathers will be related to their own negative expressiveness, with an exploratory test of whether there are effects of each parents’ depressive symptoms on the other parents’ negative emotional expressiveness, (b) parents’ negative emotional expressiveness will be associated with children’s emotional insecurity, and (c) children’s emotional insecurity will be linked with internalizing symptoms. Moreover, it is expected that parental depressive symptoms will be directly related to children’s emotional insecurity and internalizing symptoms, respectively. That is, the hypothetical pathway specified in this study is not expected to fully account for relations between parental depressive symptoms and child adjustment [1].

Method

Participants

Participants included community families from South Bend and Rochester and their surrounding areas from St. Joseph County, IN, and Monroe County, NY, respectively.. Families were recruited through flyers, postcards, schools, day care centers, local community functions, and referrals from other participants. Families were eligible to participate if they had been living together for at least 3 years at the time of recruitment, had at least one child currently enrolled in kindergarten, and were able to complete the questionnaires in English. Table 1 shows the demographics of the sample. Compared to the families recruited at W1 (N = 235), the retention rates of W2 and W3 were 96.60% and 91.49%, respectively. The retention rate of W3 (N= 215) compared to families at W2 (N = 227) was 94.71%. Overall, the sample was representative of these two areas in terms of race and median household income [29]. However, the sample included a smaller percentage of participants from Hispanic/Latino origin (3.83%) in relation to the Hispanic/Latino composition in both counties (7.50%). The participants between the two sites did not differ in terms of race, parental education, income, or marital status (ps > .05). However, compared to families from South Bend, IN, families from Rochester, NY had greater number of years of cohabitation [MRochester = 12.16, SD = 5.21; MSouth Bend = 9.88, SD = 4.22; t(234) = 3.69, p < .001]. The retained and dropped families did not significantly differ in terms of age, race, marital status, or years of cohabitation (ps > .05). They also did not differ on measures of parental depressive symptoms, marital conflict, or child functioning (ps > .05). However, the families that left the study had lower income and education levels than the families that remained in the study.

Table 1.

Demographics of the Current Sample

| Demographics | |

|---|---|

| Biological parents | |

| Mothers | 94.5% (n = 222) |

| Fathers | 87.7% (n = 206) |

| Child Gender at W1 | 45.5% boys (n = 107); 54.5% girls ( n = 128) |

| Race | |

| European American | 79.57% (n = 187) |

| African American | 15.32% (n = 36) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3.83% (n = 9) |

| Biracial | 4.26% (n = 10) |

| Other | 1.28% (n = 3) |

| Married | 88.51% (n = 201) |

| Years of cohabitation | M = 11.10 (SD = 4.84) |

| Age at W1 | |

| Mothers | M = 35.04 years (SD = 5.60) |

| Fathers | M = 36.84 years (SD = 6.14) |

| Children | M = 6.00 years (SD =.45) |

| Years of education | |

| Mothers | M = 14.44 (SD = 2.34) |

| Fathers | M = 14.55 (SD = 2.69) |

| Median household income | $40,000–54,999 (26.80%, n = 63) |

Children’s teachers also completed survey packets about the children’s internalizing symptoms. Teachers agreeing to participate were sent surveys through the mail. For each survey completed, teachers received a monetary compensation. At W1, mothers provided names of their children’s school teachers. A total of 233 teachers (99.1% of participating families; Median grade level = kindergarten) completed survey packets. W1 teachers reported knowing the child for an average of 8.25 months (SD = 7.76). At W3, mothers provided names of their current children’s school teachers. A total of 188 teachers (86.2% of participating families; Median grade level = second grade) completed survey packets. W3 teachers reported knowing the child for an average of 9.90 months (SD = 7.86).

Procedure

The current study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both sites. Participants were told that the purpose of this research was to develop an understanding of how families interact and relate to one another. To participate in the study, parents provided informed consent, whereas their children provided informed assent in addition to parental permission. Within each wave, families were invited to attend two 3-hour sessions each year. The first session was scheduled with both parents and the target child, whereas the second session involved only mothers and children. The two sessions were spaced approximately one month apart. Each family received $230, $370, and $395 in Waves 1, 2, and 3, respectively, as a token of appreciation for the time and effort of their participation.

Measures

Parental depressive symptoms

At W1, the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies measure [CES-D; 30], a measure of depressive symptoms, was completed by both mothers and fathers. Parents rated how frequently they have experienced various depressive symptoms on a scale from 0 (less than one day) to 4 (five or more days). Scores of 16 or above indicated clinical levels of depression. Attesting to the pertinence of including a full range of parental depressive symptoms in the study of child outcomes, subclinical levels of parental depressive symptoms have been associated with children’s maladjustment [31]. The CES-D scale had good internal consistencies, with alpha coefficients of .87 for mothers and .86 for fathers.

Parental negative emotional expressiveness

At W2, the 12-item Negative Expressiveness subscale of the Self-Expressiveness in the Family Questionnaire, Short Form [SEFQ; 32], was completed by both mothers and fathers to measure parents’ negative expressiveness towards other family members in a variety of settings typical for most families. Participants rated negative expressiveness on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (rarely) to 9 (frequently). A composite mean score was created for maternal and paternal expressiveness, respectively. The negativity captured by the SEFQ involves negative emotions, including anger, distress, disappointment, contempt, and hostility. Sample items include “Expressing momentary anger over a trivial irritation”, “Showing contempt for another’s actions”, and “Expressing dissatisfaction with someone else’s behavior”. Good internal consistency was found for this sample, with alpha coefficients of .84 for mothers and .86 for fathers.

Children’s emotional insecurity

At W3, the 37-item Security in the Interparental Subsystems Scale [SIMS-PR; 33] was completed by both parents as a measure of children’s emotional insecurity about interparental relations. This measure assesses parents’ evaluations of their children’s reactions to parental conflict, including emotional reactivity, behavioral dysfunction, involvement in conflict, and avoidance subscales. Participants rated negative expressiveness on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all like him/her) to 5 (a whole lot like him/her). Sample items include [my child] still seems upset after we argue, gets involved in the argument, yells at family members, and becomes very quiet and withdrawn. Reflecting the goal of obtaining robust multi-reporter assessments of emotional insecurity, mothers’ and fathers’ scores were summed for each subscale. Iinter-correlations among mothers’ and fathers’ reports for indicators of emotional insecurity were emotional reactivity, r = .09, p < .10; involvement, r = .38, p < .001; behavior dysregulation, r = .38, p < .001; and avoidance, r = .22, p < .01. Alpha coefficients for the combined mother and father scores on each subscale were .80, .86, .73, and .68.

Children’s internalizing symptoms

At W1 and W3, the Child Behavior Checklist [CBCL; 34] and Teacher Report Form [TRF; 34] were used to assess children’s internalizing problems in the first and third waves, respectively. Mothers, fathers, and teachers rated how often children exhibited withdrawn, somatic, and anxious/depressed symptoms on 3-point scales ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true). Again reflecting the goal of obtaining robust, multi-reporter assessments, the scores were averaged across parents’ and teachers’ reports for each subscale. With the exception of the correlation between maternal and teacher report of somatic complaint, all correlations across maternal, paternal, and teacher reports for both age periods were statistically significant (ranging from rs = .15 to .56, all ps < .05). Consistent with a developmental psychopathology perspective, the entire range of symptoms was employed [5, 35]. Alpha coefficients for combined parent and teacher reports on withdrawn, somatic, and anxious/depressed symptoms were .78, .87, and .73 at W1 and .78, .80, and .86 at W3.

Analytic Strategy

Prior to testing the structural model, the means, standard deviations, and correlations among all study variables were examined. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine the prospective relations between parental depressive symptoms and children’s internalizing symptoms. Consistent with current approaches to mediation based on SEM, a mediated or intervening effect of parental negative expressiveness and emotional insecurity was tested for without demonstration of the traditional requirement of a significant predictor-outcome relation [36], although it should be noted that uncorrected correlations did show several significant initial associations between W1 parental depression and W3 child symptoms. Notably, there is an emerging consensus that “a mediated effect may exist whether or not there is a statistically significant effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable” [37, p. 50] and that the “rigid requirement of the first step of Baron and Kenny’s mediation guidelines be dropped” [38, p. 430].

SEM was conducted using EQS for Windows Version 6.1 [39, 40] to test the proposed model relating parental depressive symptoms, parental negative emotional expressiveness, children’s emotional insecurity, and children’s internalizing problems (see Figure 1). The maximum likelihood method was used to examine the model fit to the observed variance and covariance matrices. Full information maximum likelihood estimation was used to handle missing data. Expanding on the work of Sobel [41], SEM is well-suited for assessments of indirect effects [42]. Child gender and autoregressive effects of W1 internalizing problems were incorporated as controls. Latent constructs were created for children’s emotional insecurity (with indicators including emotional reactivity, involvement, behavioral dysregulation, avoidance) and internalizing problems (with indicators including somatic problems, withdrawal, and anxiety or depressive symptoms) to more fully and objectively capture the underlying meanings of these constructs. To account for shared variance, error covariance within the construct of emotional insecurity and the constructs of W1 and W3 child internalizing problems were included.

Results

Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations among the variables at W1-3. Mothers and fathers exhibited similar levels of depressive symptoms (M = 8.94, SD = 7.96; M = 8.41, SD = 7.57, respectively, p > .05). At W1, 15.74% of mothers (n = 37) and 12.34% of fathers (n = 29) scored above the cut-off of 16 for clinically significant symptoms on the CES-D [30]. With regard to population reference matters, in comparison to 10 and 16% of school-age children in the general population who meet criteria for clinical and borderline clinical internalizing problems [43], respectively, a greater number of the children in our sample met the cutoff for clinical (12%, n = 28; 16 girls and 12 boys) and borderline clinical (21%; n = 50; 26 girls and 24 boys) internalizing symptoms at W1. Among these children, As to W3, 15% met the clinical cut-off (n = 33, 19 girls and 14 boys) and 26% met the cutoff for borderline clinical (n = 56; 29 girls and 27 boys) internalizing symptoms [34]. Finally, the population reference data for parental negative emotional expressiveness and child insecurity were not available.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations among Observed Variables across W1 and W3

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | - | |||||||||||||||

| 2. | .21 ** | - | ||||||||||||||

| 3. | .24 *** | .08 | - | |||||||||||||

| 4. | .11 | .37 *** | .25 *** | |||||||||||||

| 5. | 0 | .20 ** | .19 ** | .22; ** | ||||||||||||

| 6. | .06 | .24 *** | .19 ** | .58 *** | ||||||||||||

| 7. | .16 * | .16 * | .32 *** | .29 *** | .49 *** | .38 *** | ||||||||||

| 8. | .17 * | .22 ** | .20 ** | .20 ** | .64 *** | .67 *** | .34 *** | |||||||||

| 9. | .12 | .17 * | .23 ** | .19 ** | .29 *** | .30 *** | .23 ** | .31 *** | ||||||||

| 10. | .15 * | .17 * | .27 ** | .11 | .26 *** | .15 * | .20 ** | .16 * | .60 *** | |||||||

| 11. | .09 | .15 * | .18 * | .20 ** | .27 *** | .32 *** | .26 *** | .30 *** | .47 *** | .36 *** | ||||||

| 12. | .15 * | .16 * | .14 * | .12 | .30 *** | .17 * | .19 ** | .25 *** | .57 *** | .36 *** | .22 *** | |||||

| 13. | .17 * | .21 *** | .07 | .12 | .27 *** | .15 * | .17 * | .12 | .36 *** | .58 *** | .19 ** | .58 *** | ||||

| 14. | .22 *** | .23 *** | .10 | .21 ** | .27 *** | .33 *** | .20 ** | .25 *** | .28 *** | .25 *** | .49 *** | .34 *** | .40 *** | |||

| 15. | .01 | .3 | −.03 | .02 | .07 | .08 | −.08 | .17 * | 0 | .03 | .02 | −.05 | .01 | −.01 | ||

| M | 8.94 | 8.41 | 3.79 | 3.41 | 8.86 | 7.57 | 3.71 | 4.09 | 4.03 | 1.90 | 1.48 | 3.51 | 1.74 | 1.21 | - | |

| SD | 7.96 | 7.57 | .99 | 1.11 | 1.82 | 1.70 | 1.15 | .96 | 3.00 | 1.65 | 1.53 | 2.66 | 1.45 | 1.14 | - | |

Note. 1. W1 Maternal depressive symptoms; 2. W1 Paternal depressive symptoms; 3. W2 Maternal negative expressiveness; 4. W2 Paternal negative expressiveness; 5. W3 – Children’s emotional insecurity (Emotional reactivity); 6. W3 – Children’s emotional insecurity (Involvement in conflict); 7. W3 – Children’s emotional insecurity (Behavioral dysregulation); 8. W3 – Children’s emotional insecurity (Avoidance); 9. W3- Children’s Internalizing problems (Anxious/Depressed); 10. W3- Children’s Internalizing problems (Withdrawal); 11. W3- Children’s Internalizing problems (Somatic complaints); 12. W1- Children’s Internalizing problems (Anxious/Depressed); 13. W1- Children’s Internalizing problems (Withdrawal); 14. W1- Children’s Internalizing problems (Somatic complaints); 15. Gender;

p =/<.05,

p =/< .01,

p =/< .001

In comparing the sample by gender, boys and girls exhibited similar levels of internalizing symptoms at W1 (M = 2.20, SD = 1.47; M = 2.12, SD = 1. 39), and W3 (M = 2.44, SD = 1.67; M = 2.49, SD = 1.74), respectively, (ps > .05). Child gender was added as a control, given previous findings of gender differences in internalizing symptoms as children approach adolescence [44–46]. Finally, none of the current study variables differed by ethnicity (ps > .05).

To examine the relations prospectively in a structural model, data were assessed from when the children were at kindergarten to when they were at second grade. The model demonstrated adequate fit; χ2(66) = 127.92, p <.001, CFI = .93, GFI = .92, RMSEA = .07. Table 3 provides the unstandardized and standardized parameter estimates for the structural model.

Table 3.

Unstandardized and Standardized Parameter Estimates for the Finalized Structural Model

| Parameter Estimates | ||

|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized | Standardized | |

| Direct Effects | ||

| W1 Maternal depressive symptoms → W2 Maternal expressiveness | .03 (.009)** | .25 |

| W1 Maternal depressive symptoms → W2 Paternal expressiveness | .001 (.01) | .01 |

| W1 Paternal depressive symptoms → W2 Maternal expressiveness | .003 (.01) | .02 |

| W1 Paternal depressive symptoms → W2 Paternal expressiveness | .06 (.01)*** | .39 |

| W1 Maternal depressive symptoms → W3 Emotional insecurity | .003 (.006) | .03 |

| W1 Paternal depressive symptoms → W3 Emotional insecurity | .02 (.007)** | .19 |

| W1 Maternal depressive symptoms → W3 Internalizing symptoms | −.01 (.02) | −.05 |

| W1 Paternal depressive symptoms → W3 Internalizing symptoms | .005 (.02) | .02 |

| W2 Maternal expressiveness → W3 Emotional insecurity | .16 (.05)*** | .24 |

| W2 Paternal expressiveness → W3 Emotional insecurity | .11 (.05)** | .18 |

| W2 Maternal expressiveness → W3 Internalizing symptoms | .34 (.14)** | .17 |

| W2 Paternal expressiveness → W3 Internalizing symptoms | −.015 (.13) | −.009 |

| W3 Emotional insecurity → W3 Internalizing symptoms | .76 (.26)** | .25 |

| W1 Internalizing symptoms → W3 Internalizing symptoms | .68 (.09)*** | .67 |

| Child gender → W3 Internalizing symptoms | .12 (.26) | .03 |

| Indirect Effects | ||

| W1 Maternal depressive symptoms → W3 Emotional insecurity | .005 (.002)* | .06 |

| W1 Paternal depressive symptoms → W3 Emotional insecurity | .006 (.003)* | .07 |

| W1 Maternal depressive symptoms → W3 Internalizing symptoms | .02 (.008)* | .06 |

| W1 Paternal depressive symptoms → W3 Internalizing symptoms | .02 (.01) | .06 |

| W2 Maternal expressiveness → W3 Internalizing symptoms | .12 (.06)* | 8.06 |

| W2 Paternal expressiveness → W3 Internalizing symptoms | .08 (.04)* | .05 |

| Covariance | ||

| W1 Maternal and paternal depressive symptoms | 13.46 (4.42)** | .23 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

p =/< .05,

p =/< .01,

p =/< .001

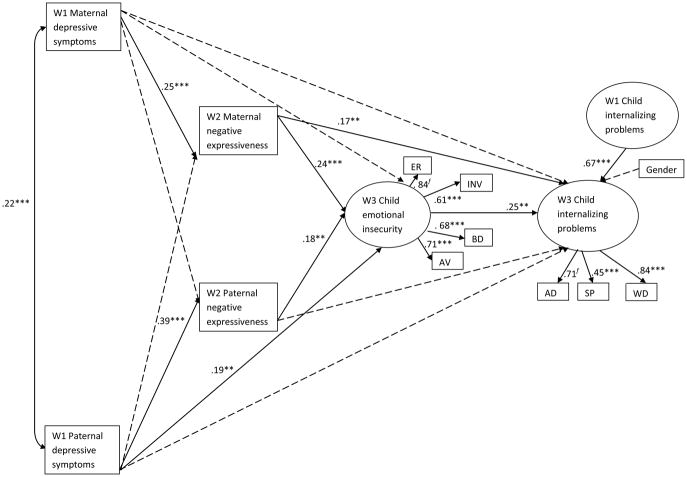

Figure 2 illustrates the prospective relations among parental depressive symptoms, parental negative expressiveness, emotional insecurity, and child internalizing problems. Findings from mediational analysis supported parental negative expressiveness and children’s emotional insecurity as significant mediators through which parental depressive symptoms influenced children’s development of internalizing symptoms. Given the autoregressive correction by symptom level at W1, the outcome shows that mediators predicted change in symptom level from W1 to W3. In terms of tests of indirect effects, W1 maternal and paternal depressive symptoms indirectly predicted W3 emotional insecurity through parental negative expressiveness (βs = .06 and .07, ps < .05). W1 maternal depressive symptoms and W2 maternal and paternal negative expressiveness indirectly predicted change in children’s internalizing symptoms at W3 through their emotional insecurity (βs = .06, .06 and .05, ps < .05, respectively).

Figure 2.

Model findings of parental depressive symptoms, parental negative emotional expressiveness and children’s emotional insecurity in predicting children’s internalizing problems. Standardized parameter estimates are presented; dashed paths denotes non-significant parameter estimates; ** p =/<.01, *** p =/< .001; χ2(66) = 127.92, p <.001, CFI = .93, GFI = .92, RMSEA = .07. f refers to parameters that are fixed to 1. Note. ER = Emotional reactivity; INV = Involvement in conflict; BD = Behavioral dysregulation; AV = Avoidance; AD = Anxious/Depressed; WD = Withdrawal; SP = Somatic problems

Discussion

The findings indicated that parental depressive symptoms predicted children’s internalizing symptoms through a pathway involving parental emotional expressiveness and children’s emotional insecurity. The significance of emotional insecurity for the effects of parental depressive symptoms on changes in children’s internalizing symptoms was thus demonstrated, advancing to the limited but growing empirical support for EST as an explanatory process in the context of parental depressive symptoms [47, 48]. The findings also indicated that multiple processes may be related to risk for the development of children’s internalizing symptoms [13, 49]. In particular, negative emotional expressiveness in the family by mothers and fathers were shown to both play roles in children’s appraisals of security. Thus, a pathway between parental depressive symptoms when children were in kindergarten and changes in children’s internalizing symptoms in second grade was supported, controlling for internalizing symptoms in kindergarten. For both parents, a pathway was identified in which relations with internalizing symptoms depended on whether parental negative emotional expressiveness elevated children’s emotional insecurity. In summary, depression itself did not influence child internalizing symptoms unless other processes were influenced. That is, parental behavior (i.e., negative expressiveness) and its influence on children’s individual psychological vulnerability (i.e., emotional insecurity) were related to the impact on child problems in this context.

Differences in influence as a function of parental gender also was identified (see Figure 2). First, paternal depressive symptoms were directly related to children’s emotional insecurity. One possible explanation is that depressive symptoms in fathers may be perceived as less acceptable or normative, so that children’s emotional insecurity is directly threatened. Second, maternal negative emotional expressiveness was directly associated with children’s internalizing symptoms. A possible explanation is that mothers’ negative emotional expressiveness predicts parenting and other aspects of family functioning that affect children’s internalizing problems, without regard to children’s emotional security. That is, as the parent who often assumes the primary caregiving role, mothers’ depressive symptoms may have a greater impact on family processes that affect children’s internalizing problems. Given these differences, future studies should further examine specific influences of paternal vs. maternal depressive symptoms.

The present study indicated an indirect “chain of events” with temporal precedence consistent with the predictions of our developmental model: Parental depressive symptoms were longitudinally linked with internalizing problems via parental expressiveness and emotional insecurity. The demonstration of a direct link between parental depressive symptoms and internalizing problems is neither a sufficient nor necessary condition for testing process-oriented models. In other words, parental depressive symptoms are no less important as predictors of children’s internalizing problems in an indirect chain of events, because without the precipitating event of parental depression, the unfolding series of pathogenic processes would not have eventuated. Parental depression ultimately undermined child internalizing symptoms by setting in motion dysfunctional familial expressions of negative emotions and insecure response processes in the child.

The utility of the construct of parental negative emotional expressiveness for understanding children’s development in families was further illustrated [21, 50]. Parental emotional expressiveness in the family was linked with both paternal and maternal depressive symptoms, supporting the role of parental negative affect in pathways through which parental depressive symptoms affect family and child functioning [5, 49, 51].

This study also demonstrated the role of children’s regulatory processes (i.e., emotional insecurity) [1, 19], associated with parental depression and their internalizing problems [52, 53]. Indexed by specific classes of behavioral responses, the emotional security system included emotional reactivity, avoidance, behavioral dysregulation, and children’s efforts to mediate in interparental discord [54]. Heightened emotional and behavioral reactivity associated with emotional insecurity may increase children’s vulnerability to developing psychological symptoms over time. For example, prolonged operation of the emotional security system, including preoccupation, vigilance, and distress associated with destructive exchanges between parents, requires considerable expenditure of psychobiological resources, leaving children with fewer resources for coping with threats, challenges, and stressors [19]. In predicting change in children’s internalizing symptoms, the current findings underscore the significance of negative family emotional environment and children’s regulatory processes associated with emotional insecurity [6, 55, 56].

Limitations of the study included autoregressive controls were limited to establishing that parental depressive symptoms were linked with relatively complex pathways associated with internalizing problems among second-grade children. Autoregressive control for all the constructs from the previous time points might further improve the robustness of the model in future studies. Next, findings were based on representative community samples, and thus may not be generalizable to clinical samples, families facing substantial hardships, or more ethnically diverse samples. Moreover, depressed parents’ reports of their children’s internalizing symptoms may be biased [57], which may artificially inflate the strength of the relationships in this study. Future studies can utilize observational measures and additional informants to strengthen the assessments. The constructs may be strengthened by including additional methods of assessment or reporters. Effect sizes for predictive relations in the model tests according to Cohen’s criteria [58] were weak to moderate, whereas the effect size for the stability of child internalizing problems was strong, which should be weighed when evaluating the relative strength of the developmental findings. In this study, the sum-scores across informants were adopted as manifest variables for some constructs and the latent constructs of emotional insecurity and internalizing problems. Ideally, it would be best to incorporate separate indicators for informants and subscales. However, due to our model complexity and the medium correlations across informants on multiple subscales, we decided to sum across informants in creating the manifest indicators. Further, it remains for future research to specify patterns of gene-environment interdependence [59] and the long-term effects of parental depressive symptoms and emotional expressiveness across developmental periods, from childhood to adolescence, on child outcomes. In addition, children’s internalizing symptoms was the focus of the present work; other pertinent specific child outcomes related to internalizing symptoms, such as suicidal ideation and substance abuse [60, 61], merit consideration in future research. Finally, the current findings may not be generalizable to single-parent households. Future studies should examine children’s emotional security in families with single parent or divorced parents. Another future goal may be to compare interactional and developmental models for the interrelations between the constructs in our model. Despite these limitations, this multi-reporter, prospective study addresses gaps in understanding specific pathways associated with emotional insecurity about interparental relations between parental depressive symptoms and child internalizing symptoms.

These findings have implications for intervention and prevention efforts, as well as clinical practice. The importance of the parents’ emotional behaviors associated with depressive symptoms was underscored [14]. A take home message of our findings is that both parents should be made aware of the impact of their expressions of emotions in the family on children’s appraisals of security and the implications of parental behaviors that undermine security for children’s subsequent adjustment. Parents may be able to reduce children’s risk for emotional insecurity and internalizing problems by altering their pattern of emotional expression towards other family members, including resolving their conflicts [19, 52, 62]. Amidst the complex mix of factors related to children’s risk for internalizing problems associated with parental depressive symptoms [6, 59], this study further illuminates factors affecting the children’s adjustment. Psychological interventions geared toward improving emotional communications in the family by parents with depressive symptoms merits future investigation.

Summary

This study uniquely adds to the growing literature concerned with identifying the family mediators of links between parental depressive symptoms and children’s adjustment. In the context of prospective test of a theoretically-based model, parental negative emotional expressiveness and children’s emotional insecurity were identified as contributing to children’s risk for internalizing symptoms (for example, anxiety, depression) in the context of parental depressive symptoms. Both paternal and maternal depressive symptoms were related by this pathway of influence to children’s internalizing symptoms. These findings suggest that children’s personal sense of safety and protection is affected by patterns of negative emotional expressiveness associated with parental symptoms, with implications for children’s adjustment problems. These results thus advance the limited but growing empirical support for EST as an explanatory model for children’s adjustment in the context of parental depressive symptoms. The utility of the construct of parental negative emotional expressiveness for children’s developmental in families was also further illustrated. A take-home message is that both parents should be made aware of the impact of their negative expressions of emotions in the family on children’s appraisals of security and the implications of parental behaviors that undermine security for children’s subsequent adjustment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health (R01 MH57318) awarded to Patrick T. Davies and E. Mark Cummings. We are grateful to the families and teachers who participated in this project. We would like to thank the project staff and students at the University of Notre Dame and the University of Rochester. We also wish to thank Scott E. Maxwell and Ziyong Zhang for their statistical consultation.

Contributor Information

E. Mark Cummings, University of Notre Dame.

Rebecca Y. M. Cheung, University of Notre Dame

Patrick T. Davies, University of Rochester

References

- 1.Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beardslee WR, Bemporad J, Keller MB, Klerman GL. Children of parents with major affective disorder: A review. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:825–832. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.7.825. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/616778054?accountid=12874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman SH. Depression in mothers. In: Nolen-Hoeksema S, editor. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. Vol. 3. 2007. pp. 107–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weissman MM, Warner V, Wickramaratne P, Moreau D, Olfson M. Offspring of depressed parents: 10 years later. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:932–940. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830220054009. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/619195536?accountid=12874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cummings EM, Davies PT, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. Guilford Publications, Inc; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis G, Rice F, Harold GT, Collishaw S, Thapar A. Investigating environmental links between parental depression and child depressive/anxiety symptoms: Using an assisted conception design. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50: 451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silberg JL, Maes H, Eaves LJ. Genetic and environmental influences on the transmission of parental depression to children’s depression and conduct disturbance. An extended Children of Twins study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51: 734–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox MJ, Paley B. Families as systems. Annu Rev Psychol. 1997;48: 243–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phares V, Compas BE. The role of fathers in child and adolescent psychopathology: Make room for daddy. Psychol Bull. 1992;111:387–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings EM, Merrilees CE, George MW. Fathers, Marriages, and Families: Revisiting and Updating the Framework for Fathering in Family Context. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 5. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York, NY: 2010. pp. 154–176. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du Rocher Schudlich T, Cummings EM. Parental dysphoria and children’s internalizing symptoms: Marital conflict styles as mediators of risk. Child Dev. 2003;74: 1663–1681. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramchandani PG, O’Connor TG, Evans J, Heron J, Murray L, Stein A. The effects of pre- and postnatal depression in fathers: A natural experiment comparing the effects of exposure to depression on offspring. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49: 1069–1078. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02000.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garber J. Depression in children and adolescents: Linking risk research and prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:S104–S125. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Restifo K, Bögels S. Family processes in the development of youth depression: Translating the evidence to treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29: 294–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxomic implications. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychol Bull. 1990;108:50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gotlib IH, Whiffen VE. Depression and martial functioning: An examination of specificity and gender. J Abnorm Psychol. 1989;89:23–30. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.98.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owen MT, Cox MJ. Marital conflict and the development of infant– parent attachment relationships. J Fam Psychol. 1997;11: 152–164. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.11.2.152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings EM, Davies PT. Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. The Guilford Press; New York and London: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies PT, Harold GT, Goeke-Morey M, Cummings EM. Child emotional security and interparental conflict. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2002;67:vii–viii. doi: 10.1111/1540-5834.00205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halberstadt AG. Family expressiveness styles and nonverbal communication skills. J Nonverbal Behav. 1983;8:14–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00986327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laible D. Maternal emotional expressiveness and attachment security: Links to representations of relationships and social behavior. Merrill Palmer Q. 2006;52: 645–670. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2006.0035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong MS, McElwain NL, Halberstadt AG. Parent, family, and child characteristics: Associations with mother- and father-reported emotion socialization practices. J Fam Psychol. 2009;23: 452–463. doi: 10.1037/a0015552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cummings EM, Cicchetti D. Towards a transactional model of relations between attachment and depression. In: Greenberg M, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, editors. Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1990. pp. 339–372. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sroufe LA, Waters E. Attachment as an organizational construct. Child Dev. 1977;49: 1184–1199. doi: 10.2307/1128475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cummings EM, Davies PT. Emotional security as a regulatory process in normal development and the development of psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 1996;8: 123–139. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400007008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cummings EM, George MW, McCoy K, Davies P. Interparental conflict in kindergarten and adolescent adjustment: prospective investigation of emotional security as an explanatory mechanism. Child Dev. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waters E, Cummings EM. A secure base from which to explore close relationships. Child Dev. 2000;49: 164–172. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S. Census Bureau. State and County QuickFacts. Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/36/36055.html.

- 30.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1: 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farmer A, McGuffin P, Williams J. Measuring psychopathology. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halberstadt AG, Cassidy J, Stifter CA, Parke RD, Fox NA. Self expressiveness within the family context: Psychometric support for a new measure. Psychol Assessment. 1995;7:93–103. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.7.1.93. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies PT, Harold GT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM, Shelton K, Rasi JA, Jenkins JM. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2002. Child emotional security and interparental conflict. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist: 4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sroufe LA. The concept of development in developmental psychopathology. Child Dev Perspect. 2009;3: 178–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51: 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7: 422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bentler PM. EQS Structural Equation Program Manual. BMDP Statistical Software; Los Angeles, CA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bentler PM. EQS 6 structural equations program manual. Multivariate Software; Encino, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sobel ME. Direct and indirect effects in linear structural equation models. Sociol Methods & Res. 1987;16:155–76. doi: 10.1177/0049124187016001006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearl J. The science and ethics of causal modeling. In: Panter AT, Sterba S, editors. Handbook of ethics in quantitative methodology. Taylor and Francis; New York, NY: 2011. pp. 383–416. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/867318042?accountid=12874. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keenan K, Hipwell AE. Preadolescent clues to understanding depression in girls. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2005;8: 89–105. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-4750-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychol Bull. 1994;115: 424–443. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zahn-Waxler C, Klimes-Dougan B, Slattery MJ. Internalizing problems of childhood and adolescence: Prospects, pitfalls, and progress in understanding the development of anxiety and depression. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12: 443–466. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400003102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Du Rocher Schudlich T, Cummings EM. Parental dysphoria and children’s adjustment: Marital conflict styles, children’s emotional security, and parenting as mediators of risk. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35: 627–639. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kouros CD, Merriless CE, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and children’s emotional security in the context of parental depression. J Marriage Fam. 2008;70: 684–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychol Rev. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Halberstadt AG. Of models and mechanisms. Psychol Inq. 1999;9:290–294. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kessler RC, Zhao S, Blazer DG, Swartz M. Prevalence, correlates, and course of minor depression and major depression in the national comorbidity survey. J Affect Disord. 1997;45:19–30. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dix T, Meunier LN. Depressive symptoms and parenting competence: An analysis of 13 regulatory processes. Dev Rev. 2009;29:45–68. doi: 10.1026/j.dr.2008.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eisenberg N, Gershoff ET, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Cumberland AJ, Losoya SH, et al. Mother’s emotional expressivity and children’s behavior problems and social competence: Mediation through children’s regulation. Dev Psychol. 2001;37: 475–490. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harold GT, Shelton KH, Goeke-Morey M, Cummings EM. Marital conflict, child emotional security about family relationships and child adjustment. Soc Dev. 2004;13: 350–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2004.00272.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kane P, Garber J. The relations among depression in fathers, children’s psychopathology, and father-child conflict: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24: 339–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilson S, Durbin CE. Effects of paternal depression on fathers’ parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30: 167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Najman JM, Williams GM, Nikles J, Spence S, Bor W, O’Callaghan M, et al. Mother’s mental illness and child behavior problems: Cause-effect association or observation bias? J Am Acad Child Psy. 2000;39:592–602. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200005000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.15558.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Shelton KH, Harold GT. Interparental conflict, negative parenting, and children’s adjustment: Bridging links between parents’ depression and children’s psychological distress. J Fam Psychol. 2008;5: 712–724. doi: 10.1037/a0013515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rutter M. Gene-environment interdependence. Devel Sci. 2007;10: 12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Innamorati M, De Leo D, Rihmer Z, et al. Tobacco smoking and suicidal ideation in school-aged children 12–15 years old: Impact of cultural differences. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2011;30(4):359–367. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2011.609802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pompili M, Innamorati M, Szanto K, et al. Life events as precipitants of suicide attempts among first-time suicide attempters, repeaters, and non-attempters. Psychiatry Res. 2011;186(2–3):300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shelton KH, Harold GT. Interparental conflict, negative parenting, and children’s adjustment: Bridging links between parents’ depression and children’s psychological distress. J Fam Psychol. 2008;5: 712–724. doi: 10.1037/a0013515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]