Abstract

Objective

Little is known about the prevalence of child obesity in the U.S. before the first national survey in 1963. There is disagreement about whether the obesity epidemic is entirely a recent phenomenon or a continuation of longstanding trends.

Methods

We analyze the BMIs of 1,116 children who participated in the Fels Longitudinal Study near Dayton, Ohio. Children were born between 1930 and 1993 and measured between 3 and 18 years of age.

Results

Between the birth cohorts of 1930 and 1993, the prevalence of obesity rose from 0% to 14% among boys and from 2% to 12% among girls. The prevalence of overweight rose from 10% to 28% among boys and from 9% to 21% among girls. The mean BMI Z-score rose from +0.25 to +0.72 among boys and from −0.11 to +0.26 among girls. Among boys, all these increases began after birth year 1970. Among girls, obesity began to rise after birth year 1970, but overweight and BMI Z-scores were already rising as early as the 1930s and 1940s.

Conclusions

Most of the results suggest that the child obesity epidemic was recent and sudden. The recency of the epidemic offers some hope that it may be reversed.

Introduction

The history of U.S. children’s body mass index (BMI) relies primarily on national surveys which started in 1963. According to those surveys, the distribution of children’s BMI was stable from the 1960s until the 1980s and then rose until the 2000s. The prevalence of obesity (as defined by the IOTF1) rose from under 5% to over 10% of children, and the prevalence of overweight rose from approximately 15% to over 30%2.

Earlier trends are not as clear. Before the 1960s, there were no national health surveys, and the most comprehensive height and weight measurements come from military conscripts—i.e., selected young men at least 18 years of age. Mean BMI among military conscripts rose about 0.5 kg/m2 between the Civil War and World War Two, then rose another 1.0 kg/m2 between World War Two and the first national health surveys in the 1960s.3 It is unknown whether trends were similar for males under 18 years or for females of any age. Two recent studies4,5 have tried to extrapolate backward—starting with BMIs measured on older participants in national surveys from the 1960s–2000s, then estimating, under assumptions about growth, what the same individuals’ BMIs would have been decades earlier. One extrapolation study estimated that mean BMI has risen steadily since the birth cohort of 1883, concluding that “the obesity epidemic began earlier than hitherto thought,”4 but another extrapolation study, using different data and different assumptions, estimated that age-adjusted obesity prevalence actually declined between the birth cohorts of 1890 and 19555.

In this paper, we estimate historic trends in a sample of children of both sexes and all ages from 3 to 18 years, measured longitudinally from the Great Depression until the present. The sample is not nationally representative, but because it has continued into recent years we can compare recent cohorts to national data and evaluate the size of any differences.

Data

Since 1929 the Fels Longitudinal Study6 (FLS) has recruited children primarily from three counties in the Dayton, Ohio metropolitan area. Today 31% of the adults in these counties are obese, which is close to the median obesity prevalence of 30% across all U.S. counties.7 The FLS is a convenience sample that has often enrolled multiple generations of the same families; one consequence is that 98% of FLS participants are non-Hispanic whites—a figure that is much closer to the Dayton area’s demographics at the start of the FLS in 1929 than today.8 Notwithstanding the FLS’s ethnic homogeneity, the FLS is socioeconomically diverse; the socioeconomic characteristics of FLS families are similar to those of the U.S. population except that the FLS underrepresents families in the bottom quintile of socioeconomic status.6

Our analyses begin with children born in 1930, the first full year of the study, and end with children born in 1993, who are the most recent cohort to reach age 18 years. We use measurements from age 3 years—when FLS children’s heights are first measured standing up rather than lying down—through age 18 years. The FLS schedules measurements once or twice per year, and half of longitudinal participants have attended at least 85% of their scheduled visits. Our analysis excludes 7 pairs of twins and 20 non-white children; we also excluded measurements on 9 girls who were pregnant at the time of measurement.

We analyze 18,731 measurements on 570 boys and 546 girls—an average of 16 measurements per child, or one measurement per child per year. Table 1 summarizes the sample size and age at measurement for FLS participants by sex and birth year. The slight increase in mean age at measurement during birth years 1974 to 1981 reflects a temporary suspension of new enrollments due to reduced funding. During the enrollment suspension, the FLS continued to measure previously enrolled children, and after the suspension the FLS recruited older children who had been born in 1974 to 1981. (Excluding these older recruits does not materially affect our results.) Note that gaps have also occurred in national surveys; for example the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) did not examine any children between 1980 and 1988.

Table 1.

Participation in the Fels Longitudinal Study

| a. Boys

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth Year | Participants | Measurements | Mean | Minimum | Maximum |

| 1930 to 1934 | 34 | 799 | 10.48 | 3.00 | 18.08 |

| 1935 to 1944 | 76 | 1612 | 10.37 | 3.00 | 18.30 |

| 1945 to 1954 | 88 | 1856 | 10.47 | 3.00 | 18.65 |

| 1955 to 1964 | 113 | 1874 | 10.36 | 3.00 | 18.70 |

| 1965 to 1974 | 106 | 1544 | 10.25 | 3.00 | 18.57 |

| 1975 to 1984 | 65 | 979 | 11.67 | 3.00 | 18.64 |

| 1985 to 1993 | 88 | 956 | 10.73 | 3.00 | 18.89 |

| b. Girls

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth Year | Participants | Measurements | Age

|

||

| Mean | Minimum | Maximum | |||

| 1930 to 1934 | 42 | 956 | 10.30 | 3.00 | 18.15 |

| 1935 to 1944 | 73 | 1477 | 10.40 | 3.00 | 18.99 |

| 1945 to 1954 | 66 | 1283 | 10.47 | 3.00 | 18.60 |

| 1955 to 1964 | 132 | 2168 | 10.19 | 3.00 | 18.91 |

| 1965 to 1974 | 90 | 1345 | 10.03 | 3.00 | 18.80 |

| 1975 to 1984 | 60 | 890 | 11.03 | 3.01 | 18.85 |

| 1985 to 1993 | 83 | 992 | 9.91 | 3.00 | 18.97 |

Methods

At each measurement occasion we calculate a BMI Z-score and variables indicating whether a child was obese, overweight (including obese), or thin (grade 1) according to the IOTF standards.10 We also calculate the same quantities—a Z-score and indicators of obesity, overweight, and underweight—using the U.S. CDC standards11.

We estimate trends by regressing each outcome variable on year of birth. We use linear regression to model the Z-score and logistic regression to model the indicators of obesity, overweight, and thinness. Serial correlations between measurements taken on the same child are modeled using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with an exchangeable correlation structure. Year of birth was coded in two different ways. First we coded indicator variables for each of the birth-year ranges in Table 1. Next we fit a smooth trend using natural quadratic spline functions of birth year with a single interior knot at 1963. We also fit cubic splines with two or three interior knots, as well as local regression (loess) models, but these more complicated approaches did not materially change the estimated trends. We estimated the significance (p value) of each trend using a chi-square test that compares the fit of the spline model to the fit of a no-trend model with only an intercept.

Results

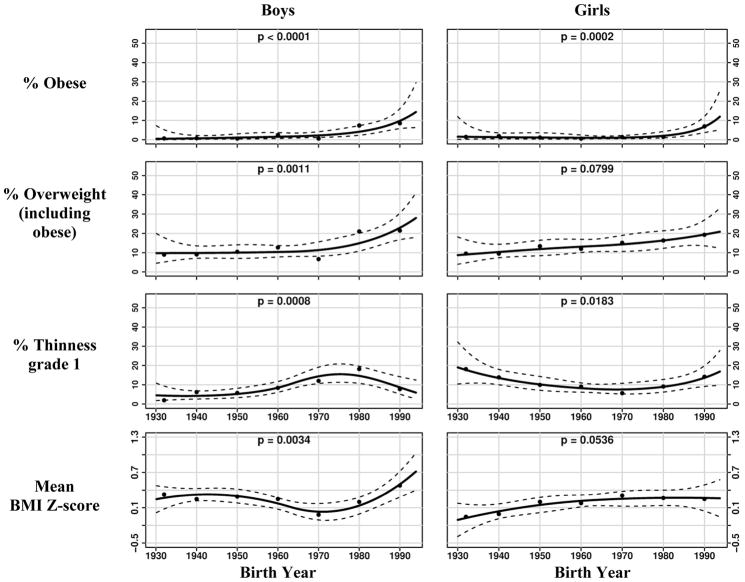

Figure 1 displays the trends for boys and girls in the FLS, using the IOTF standards. The trends show that the obesity epidemic has affected FLS participants. Between the birth cohorts of 1930 and 1993, the prevalence of obesity rose from 0% to 14% among FLS boys and from 2% to 12% among FLS girls. The prevalence of overweight rose from 10% to 28% among boys and from 9% to 21% among girls.

Figure 1.

Smoothed trends of prevalences and mean BMI Z-score based on the extended IOTF standards. Solid lines are quadratic splines with a single knot in 1963; dashed lines are 95% pointwise confidence intervals; points are prevalences or means within birth year groupings corresponding to those in Table 1. P-values are for tests of the null hypothesis that the trend is flat. The trend in girls’ overweight was also fit to a straight line; under that simplified model, the trend was significant at P=.01.

Most of the FLS results suggest that the obesity epidemic is a recent phenomenon. The prevalence of obesity was low and flat between birth years 1930 and 1970, and then rose, starting around birth year 1970 for boys and 1980 for girls. Overweight among FLS boys also began to rise around birth year 1970, but overweight among FLS girls suggests a more gradual uptrend that may have begun as early as birth year 1940. After 1970, the timing of the FLS obesity epidemic is consistent with national data, where the rise in obesity was first noticed in 1988–94 among children born in the 1970s and 1980s.2

FLS trends for thinness are inconsistent. For boys, thinness prevalence rose from birth year 1950 until 1970–1980 and then declined; the decline is consistent with national data showing that the prevalence of underweight declined slightly after 1970.12 For FLS girls, however, thinness prevalence declined until birth year 1970 or so, and then rose. The discrepancy between the thinness of boys and girls was greatest among children born at the start of the Great Depression, around 1930, when just 5% of boys but nearly 20% of girls were thin.

FLS trends in mean BMI Z-score are influenced by both the top and bottom of the BMI distribution. For the most part, mean Z-scores rise when overweight rises or thinness falls, but for girls after birth year 1970 mean Z-scores are flat since overweight and thinness are rising simultaneously. Overall, between the birth years of 1930 and 1993, the mean BMI Z-score rose from +0.25 to +0.72 among boys and from −0.11 to +0.26 among girls.

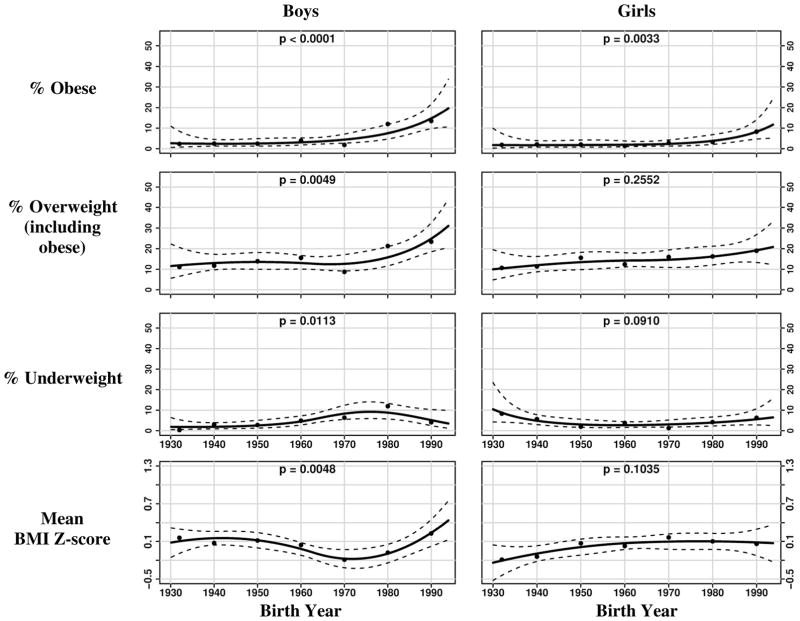

For boys, the prevalence of obesity in the FLS is comparable to the prevalence in national surveys such as the NHANES; for girls, obesity prevalence is somewhat lower in the FLS than it is in the NHANES. This is true even if we restrict the NHANES to children who, like our FLS sample, are non-Hispanic whites. To compare the FLS to the NHANES, in Figure 2 we re-estimate the FLS trends using the CDC’s definition of obesity, which is the only definition that has been used to estimate race-specific trends in the NHANES.9 Under the CDC definitions, obesity prevalence among FLS boys rose from 4–5% in birth years 1960–1970 to 20% in birth year 1993; this matches closely the trend for white boys in the NHANES, whose obesity prevalence rose from 5% among boys measured in 1971–74 (who were born in the 1960s) to 19% among boys measured in 2003–04 (who were born, on average, in 1993).9 Among girls, CDC-defined obesity in the FLS rose from 2–3% in birth years 1960–1970 to 12% in birth year 1993; this is somewhat below the trend for white girls in the NHANES, whose obesity prevalence rose from 4% among girls measured in 1971–74 (who were born in the 1960s) to 16% among girls measured in 2003–04 (who were born, on average, in 1993).9

Figure 2.

Smoothed trends in prevalences and mean BMI z-score. The methods and data are the same as in Figure 1, but here the definitions of obesity, overweight, underweight, and Z-score are based on the CDC standards8,12 rather than the IOTF standard.

Conclusion

This report offers a glimpse of local BMI trends before the first U.S. national surveys in the 1960s. Among boys, the results suggest that rising BMIs are a recent phenomenon; the male BMI distribution was fairly stable from birth year 1930 until birth year 1970, and then overweight and obesity began to rise rapidly. Among girls, the rise in obesity is just as recent, although it was foreshadowed by an earlier rise in overweight and decrease in underweight. Overall, the worst part of the obesity epidemic appears fairly recent—a finding that offers some hope that the epidemic can be reversed.

What is already known

The prevalence of child obesity in the U.S. was stable through the 1960s and 1970s, then began to rise in the 1980s.

There were no national surveys of child obesity before 1963.

There is disagreement about whether the obesity epidemic is entirely a recent phenomenon or a continuation of earlier trends.

What this study adds

We use data from a local study near Dayton, Ohio, to extend the history of child obesity back to the 1930s.

Although girls’ BMIs were already increasing in the 1930s, obesity among both girls and boys was very rare until obesity prevalence began to increase after birth year 1970.

The results fit the view that the obesity epidemic is primarily a recent phenomenon.

Acknowledgments

Nahhas was supported by NIH grant R01-HD012252. Nahhas had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Contributors: Von Hippel conceived the study and led the writing, Nahhas led the data analysis. Both authors collaborated on the research design.

Contributor Information

Paul T. von Hippel, Email: paulvonhippel@austin.utexas.edu.

Ramzi W. Nahhas, Email: ramzi.nahhas@wright.edu.

Reference List

- 1.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320(7244):1240. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lobstein T, Jackson-Leach R. Child overweight and obesity in the USA: Prevalence rates according to IOTF definitions. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity. 2007;2(1):62–64. doi: 10.1080/17477160601103948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa D, Steckel RH. Long-Term Trends in Health, Welfare, and Economic Growth in the United States. In: Steckel RH, Floud R, editors. Health and Welfare during Industrialization. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1997. pp. 47–90. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Komlos J, Brabec M. The trend of mean BMI values of US adults, birth cohorts 1882–1986 indicates that the obesity epidemic began earlier than hitherto thought. American Journal of Human Biology. 2010;22(5):631–638. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.21055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reither EN, Hauser RM, Yang Y. Do birth cohorts matter? Age-period-cohort analyses of the obesity epidemic in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(10):1439–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roche AF. Growth, maturation, and body composition: the Fels Longitudinal Study 1929–1991. Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed November 28, 2011];County-Specific Obesity, Diabetes, and Physical Inactivity Prevalence. 2011 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/trends.html.

- 8.US Census Bureau. 1930 Census of Population and Housing. Washington DC: Government Printing Office; 1932. [Accessed December 21, 2012]. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/www/abs/decennial/1930.html. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The Obesity Epidemic in the United States—Gender, Age, Socioeconomic, Racial/Ethnic, and Geographic Characteristics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29(1):6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatric Obesity. 2012;7(4):284–294. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barlow SE Expert Committee. Expert Committee Recommendations Regarding the Prevention, Assessment, and Treatment of Child and Adolescent Overweight and Obesity: Summary Report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Supplement):S164–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Underweight Among Children and Adolescents: United States, 2007–2008. Washington, DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. [Google Scholar]