Abstract

We investigated the photosynthetic capacity and plant growth of tobacco plants overexpressing ice plant (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L.) aquaporin McMIPB under (1) a well-watered growth condition, (2) a well-watered and temporal higher vapor pressure deficit (VPD) condition, and (3) a soil water deficit growth condition to investigate the effect of McMIPB on photosynthetic responses under moderate soil and atmospheric humidity and water deficit conditions. Transgenic plants showed a significantly higher photosynthesis rate (by 48 %), higher mesophyll conductance (by 52 %), and enhanced growth under the well-watered growth condition than those of control plants. Decreases in the photosynthesis rate and stomatal conductance from ambient to higher VPD were slightly higher in transgenic plants than those in control plants. When plants were grown under the soil water deficit condition, decreases in the photosynthesis rate and stomatal conductance were less significant in transgenic plants than those in control plants. McMIPB is likely to work as a CO2 transporter, as well as control the regulation of stomata to water deficits.

Keywords: CO2 transporter, Atmospheric humidity, Mesophyll conductance, Mesophyll anatomy

Introduction

To perform leaf photosynthesis, CO2 must diffuse from the atmosphere to the site of carboxylation in stroma through leaf mesophyll. The diffusional conductance of CO2 through the stomata and mesophyll is called stomatal conductance (g s) and mesophyll conductance (g m), respectively, where the limitation of photosynthesis by g m is almost equal, or even larger, than that by g s (Yamori et al. 2006). In determining g m, conductance in the liquid phase, which is across the cell wall, plasma membrane, cytosol, chloroplast envelope, and stroma, is important. Among the possible factors affecting liquid phase conductance, the surface area of chloroplasts facing the intercellular air space, Sc, is important as the active area for CO2 diffusion to chloroplast stroma (Hanba et al. 2004; Terashima et al. 2006, 2011).

Recent studies suggest that some plant aquaporins (water channel proteins that transport water molecules) in the plasma membrane and chloroplast envelope are CO2 transport candidates that reduce the diffusional resistance of CO2. To date, three aquaporins including NtAQP1, AtPIP1;2, and HvPIP2;1 have been shown to reduce the diffusional resistance of CO2 in leaves. Uehlein et al. (2003, 2008) showed that tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) aquaporin NtAQP1 functions as a CO2 transporter by in vitro analysis using a heterologous expressing system in Xenopus oocytes, and also by in vivo analysis using RNA interference mediated decreases in NtAQP1. Recently, Arabidopsis thaliana aquaporin AtPIP1;2 was shown to be a CO2 transporter with the yeast heterologous expression system (Heckwolf et al. 2011). Hanba et al. (2004) and Flexas et al. (2006) reported the possibility of CO2 permeability on plant aquaporin in vivo; barley aquaporin HvPIP2;1 and tobacco aquaporin NtAQP1 overexpressing plants increased g m more than control plants. However, tobacco aquaporin NtPIP2;1 was shown to have no CO2 permeability (Otto et al. 2010), suggesting that CO2 permeability differs largely between aquaporins. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of aquaporin on CO2 diffusion in leaves.

On the other hand, some aquaporins play a role in water transport in plants, which affects plant responses to drought. However, the relationship between aquaporin expression and plant responses to drought stress is controversial. Aharon et al. (2003) reported that tobacco plants overexpressing Arabidopsis thaliana aquaporin PIPb wilted faster than control plants under drought conditions. Barley aquaporin HvPIP2;1 overexpressing rice plants grew less under salt stress (Katsuhara et al. 2003). On the other hand, NtAQP1 anti-sense tobacco plants showed lower tolerance to water stress (Siefritza et al. 2002). Lowland rice overexpressing RWC3, which is strongly expressed in upland rice, achieved drought avoidance under drought stress (Lian et al. 2004).

Leaf photosynthetic responses to drought vary largely between species (Chaves et al. 2009), which is an important factor relating whole-plant responses to drought. Both a soil water deficit and atmospheric vapor water deficit (VPD) should be considered to understand plant photosynthetic responses to drought. Although the effect of a soil water deficit on the limitation of plant photosynthesis has been extensively studied (Chaves et al. 2009; Flexas et al. 2009), the effect of aquaporin on the photosynthetic response to a soil water deficit has scarcely been studied. Although the effects of VPD on the regulation of g s have been extensively observed (Day 2000; Shirke and Pathre 2004; Warren 2008), the role of aquaporin on the regulation of g s to changes in VPD has not been studied yet. Aquaporin overexpressing plants tend to increase g s under non-water-stressed conditions (Flexas et al. 2006; Hanba et al. 2004), suggesting the role of aquaporin in stomatal regulation. Furthermore, specific aquaporins are highly expressed in guard cells (Fraysse et al. 2005; Kaldenhoff et al. 1995; Otto and Kaldenhoff 2000; Sun et al. 2007). The controversy among previous studies for the relationship between the level of aquaporin expression and plant responses to drought may be due to differences in the stomatal response to VPD and/or a soil water deficit via aquaporin, which was scarcely considered in previous studies. In this study, we investigated the role of aquaporin on the plant response to a water deficit by changing VPD and the soil water content to clarify the effect of aquaporin on stomatal regulation to a water deficit.

In this study, we focused on the role of the ice plant (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L.) aquaporin, McMIPB (Accession L36097), in leaf photosynthesis. M. crystallinum is native to southern and eastern Africa, and is a halophyte with a developmentally programmed switch from C3 photosynthesis to crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) that is accelerated by salinity and drought (Adams et al. 1998). McMIPB has been identified as a PIP1 type aquaporin (Yamada et al. 1997) and is mainly located at xylem parenchyma in the ice plant (Kirch et al. 2000). Yamada et al. (1995) described that ice plant aquaporin McMIPB transcript products were unchanged relative to the other ice plant aquaporin transcripts, McMIPA and McMIPC, during salt stress treatment. We estimate that McMIPB plays an important role under drought conditions in maintaining water balance in the plant body and its photosynthetic capacity.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the role of McMIPB, a new candidate for enhancing CO2 diffusion and regulating stomata, on leaf photosynthesis, plant growth, and plant responses to a water deficit. We compared control plants and overexpression McMIPB plants grown under three different conditions: (1) a well-watered growth condition, (2) a well-watered and temporal higher VPD condition, and (3) a soil water deficit growth condition. The localization of McMIPB inside leaves, photosynthetic parameters, and plant growth were compared between controls and overexpressed plants grown in the well-watered condition to determine the roles of McMIPB in CO2 diffusion, leaf photosynthesis, and growth. Leaf mesophyll anatomy was analyzed to investigate the effects of mesophyll anatomy on CO2 diffusion. The responses of leaf photosynthetic parameters, levels of McMIPB protein levels, and plant growth were then investigated for temporal higher VPD and the water deficit growth condition to clarify the roles of McMIPB in stomatal regulation to a water deficit.

Materials and methods

Transformation of tobacco

A full length of McMIPB (Accession No. L36097) cDNA was inserted downstream from a 35S-promoter in the expression vector pBI121. The transformation of the tobacco leaf disk with Agrobacterium methods, regeneration, and the selection of transgenic plants with kanamycin (100 mg/L) were performed as previously described (Horsch et al. 1985). T2 generation of McMIPB overexpressing tobacco, line 8884, was made based on non-transgenic tobacco plants, line SR. The parents of line 8884 were homozygotes.

Plant growth

Seeds of tobacco plants were sowed on an agar medium and grown in a growth chamber (LPH-350S, NK system, Japan) under the following conditions: temperatures of 25/18 °C (day/night), a photoperiod of 16/8 h (day/night), relative humidity of 70 %, and PPFD of 300 μmol m−2 s−1. When cotyledons expanded, plants were transplanted to 0.5 L plastic pots filled with culture soil (green soil, Tankyo, Japan) and akadama pumice (7:3, volume ratio). They were watered daily, and were fertilized once a week with a Hoagland solution. We used small plants with 5–6 leaves grown for 1 month after seeding until experiments were started. Tobacco plants had shade leaves in the present study under the growth conditions of the growth chamber.

Generation of an antibody and measurement of the protein levels of aquaporin

A polyclonal antibody was raised against a synthetic oligopeptide corresponding to QPSQYEM in loop C of McMIPB. Leaf disks (1.77 cm2 × 2) were obtained from the central part of the lamina to analyze the protein levels of aquaporin. Total protein extraction, SDS-PAGE, and protein blotting were performed as described previously (Katsuhara et al. 2002). Bands detected in the Western blot were scanned and analyzed using software (Densitograph, ATTO, Tokyo, Japan). The antibody recognized bands in SR lines as well as 8884 lines. The total level of bands was mentioned as McMIPB.

Identification of the localization of aquaporin by immunostaining

Some sections of 2 × 3 mm were obtained from leaves, and were fixed into a solution containing 3.7 % formaldehyde, 5.0 % acetic acid, and 50 % ethanol. Sections were blocked with 1 % bovine serum albumin in PBS–Tween-20 (0.2 %) and were then reacted with a solution containing 1/500 of McMIPB antibodies. Sections were reacted with a 1/500 solution of the second antibody anti-rabbit IgG (Alexa Fluor® 488 Conjugate, Life Invitrogen, Japan). Localization of the aquaporin detected by the McMIPB antibody (McMIPB) was observed using a fluorescence microscope (BX51, Olympus, Japan). To analyze the occurrence of non-specific responses, negative control analysis was examined. Immunostaining was performed on leaf sections as described previously, without the step of incubation with the first antibodies.

Gas exchange measurement and estimation of mesophyll CO2 conductance

Gas exchange measurements were performed for intact leaves under PPFD of 700 μmol m−2 s−1 and ambient CO2 concentration of 360 ppm for all experiments. Measurements were started 2 h after the chamber’s lights were on. For experiment 1, gas exchange was measured at ambient VPD (551 ± 107 Pa) for SR and 8884 lines grown under the well-watered condition. Plants were irrigated every day. The leaf temperature was 25 °C. For experiment 2, gas exchange was compared between ambient VPD (890 ± 130 Pa) and higher VPD (1630 ± 120 Pa) for SR and 8884 lines grown under the well-watered growth condition. Plants were irrigated every day. Leaf temperatures were 25 and 28 °C for ambient and higher VPD measurements, respectively. For experiment 3, plants were grown under the well-watered condition (watered every day) for 1 month after seeding, and then when 5–6 leaves expanded, the drought treatment (watered once a week) was performed for 1 month. Changes in gas exchange parameters by the drought treatment were compared between SR and 8884 lines. Gas exchange measurements were performed every day for 7 days from the next day of the last irrigation of the drought treatment. On the 6th day, plants were re-watered after gas exchange measurements were completed for the day. Leaf temperature was 26 °C, and VPD was 1002 ± 85.5 Pa.

Gas exchange parameters were calculated according to the modified method of von Caemmerer and Evans (1991). Mesophyll conductance (g m) was estimated for intact leaves by concurrent measurement of gas exchange and the carbon isotope ratio (Hanba et al. 2002) using the laboratory-constructed system described by Hanba et al. (1999). The isotope method is considered the most reliable for the estimation of g m. In the present study, g m was calculated using the simplified equation reported by Scartazza et al. (1998):

|

1 |

where Δ is the observed carbon isotope discrimination, Δi is the expected carbon isotope discrimination assuming infinite g

m, A the assimilation rate, C

a the CO2 partial pressure in ambient air, a

i the carbon isotope discrimination during CO2 diffusion/hydration into water (1.8 %), and b is the carbon isotope discrimination caused by carboxylation by Rubisco and PEP carboxylase (28.2 ‰). The symbols f and  represent discrimination with photorespiration and a CO2 compensation point without day respiration. Recently, g

m has been estimated in detail with changes in light intensity, CO2 concentration, leaf anatomy, activity of photosynthetic enzymes, and for different genotypes, where the effect of f on g

m is considered (Barbour et al. 2010; Kodama et al. 2011; Tazoe et al. 2009, 2011). Here, we assumed the effect of f was negligible because we examined it with the same light intensity, CO2 concentration, and plant materials. Measurements were repeated twice for each leaf sample. Δ was calculated from carbon isotope ratios of CO2 in the air leaving and entering the gas exchange chamber. CO2 samples were collected using dry ice–ethanol and liquid nitrogen traps. The carbon isotope ratio was determined with an isotope mass spectrometer (Finnigan MAT 252, Bremen, Germany). Analysis of the carbon isotope ratio was performed as described by Hanba et al. (1999).

represent discrimination with photorespiration and a CO2 compensation point without day respiration. Recently, g

m has been estimated in detail with changes in light intensity, CO2 concentration, leaf anatomy, activity of photosynthetic enzymes, and for different genotypes, where the effect of f on g

m is considered (Barbour et al. 2010; Kodama et al. 2011; Tazoe et al. 2009, 2011). Here, we assumed the effect of f was negligible because we examined it with the same light intensity, CO2 concentration, and plant materials. Measurements were repeated twice for each leaf sample. Δ was calculated from carbon isotope ratios of CO2 in the air leaving and entering the gas exchange chamber. CO2 samples were collected using dry ice–ethanol and liquid nitrogen traps. The carbon isotope ratio was determined with an isotope mass spectrometer (Finnigan MAT 252, Bremen, Germany). Analysis of the carbon isotope ratio was performed as described by Hanba et al. (1999).

Analysis of leaf mesophyll anatomy

For experiment 1, leaf mesophyll anatomy was determined using light micrographs. Some sections of 2 × 3 mm leaves were fixed in 2.5 % glutaraldehyde and 2 % osmium tetroxide, and were then embedded in a replacement of Spurr’s resin (Low Viscosity Resin kit, TAAB, United Kingdom). Transverse sections 700 nm thick were stained with a 1 % toluidine blue solution. Light micrographs were taken using a digital camera (VB-7000, Keyence, Japan), which was attached to a light microscope (BX51, Olympus, Japan). Anatomical characteristics were determined from digitized images of micrographs taken at 200× magnification. Surface areas of mesophyll cells and chloroplasts exposed to intercellular air spaces per unit leaf area (S mes and S c) were estimated for transverse sections as described previously (Hanba et al. 2002).

Measurements of plant growth and water content

For experiment 1, stem diameters and dry weights of shoots were measured in 4-month-old plants. Leaf area was measured in 2-month-old plants. For experiment 2, relative water content (RWC) was measured in 2-month-old plants. For experiment 3, stem diameters, dry weights of shoots and roots, and plant heights were measured in 14-week-old plants.

Stem diameter was measured using a digital caliper (CD-20C, Mitutoyo, Japan) 10 cm from the soil surface for experiment 1, and 5 cm from the soil surface for experiment 3. To determine the dry weight, shoots or roots were dried at 70 °C for 48 h and weighed. Leaf area was calculated by scanning leaves used for gas exchange measurements, using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, MD, USA). To obtain RWC, leaf disks (1.77 cm2) were harvested and their fresh weight (FW) was determined. After being soaked over 12 h in ion-exchanged water at 4 °C, their turgid weight (TW) was measured. They were then dried at 70 °C for 24 h and their dry weight (DW) was obtained. RWC was then calculated as follows:

|

Measurements of Rubisco content

Leaf disks (1.77 cm2) were obtained from the central part of the lamina, and were homogenized immediately at 4 °C in HEPES buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.2 % Triton X-100, 0.7 % 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM monoiodoacetic acid, 25 % glycerol, 6 % lithium lauryl sulfate, 1 % polyvinyl polypyrrolidone, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride. The homogenate was immediately centrifuged, and the supernatant was boiled for 5 min in Laemmli (1970) buffer. Proteins in supernatants were separated by SDS-PAGE, and gels (12.5 %) were stained with a solution (Coomassie brilliant blue, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Japan). The level of Rubisco subunits was determined spectrophotometrically by scanning the gel with a scanner (GT7600U, Epson, Tokyo, Japan). Results were analyzed using software (Densitograph, ATTO, Tokyo, Japan). The level of Rubisco was determined using BSA (BSA standard set, Bio-Rad, Japan) as the standard. The Rubisco content may be different from estimations using the extraction method by Makino et al. (1985).

Statistical analysis

Differences in mean values between transgenic and control plants were analyzed using an unpaired t test and paired t test.

Results

The level and localization of McMIPB

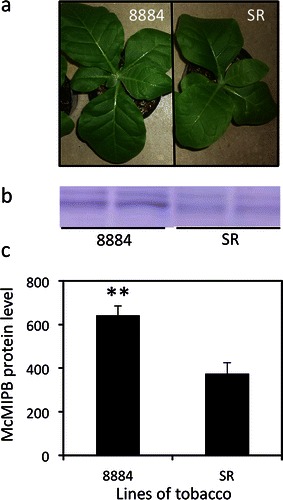

The size of the tobacco plant was larger in line 8884 than that in line SR (Fig. 1a). The protein band detected by the McMIPB antibody (McMIPB) was observed in both SR and 8884 lines (Fig. 1b). The level of McMIPB was 71 % higher in 8884 than that of SR (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Images of whole plant and protein levels of aquaporins detected by the McMIPB antibody (McMIPB). a Images of lines 8884 and SR grown for 1 month after seeding, b levels of McMIPB, and c intensity of McMIPB protein levels that were densitometrically quantified by Western analysis, where values are mean ± SE from different plants (n = 3–5). Statistical analysis was done using an unpaired t test. Asterisks above bars indicate that the means of transgenic plants are significantly different from the SR line (p < 0.01)

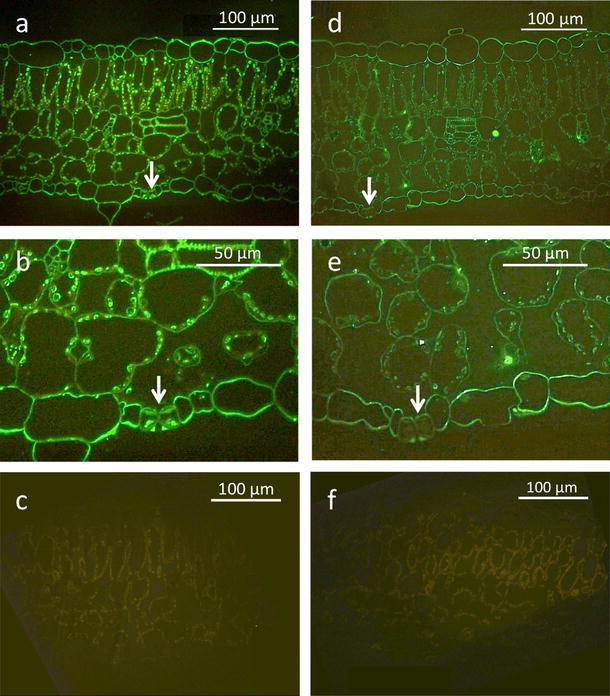

In line 8884, the strongest McMIPB signals were detected at chloroplasts in mesophyll cells and also at chloroplasts in stomata (Fig. 2a, b). Signals were also detected at vascular bundles and epidermal cells. In the SR line, weak signals were detected at chloroplasts in mesophyll cells (Fig. 2d, e). Signals at chloroplasts in stomata were very weak. Significant signals were detected at vascular bundles and epidermal cells. Mesophyll cells were slightly tinged with red due to the auto-fluorescence of chloroplasts in both lines, but non-specific responses were not detected in either line (Fig. 2c, f).

Fig. 2.

Localization of McMIPB in the leaf mesophyll of tobacco plants grown under the well-watered condition. a–c Line 8884, and d–f line SR. Florescence micrographs were taken at ×400 magnification. c, f Negative controls of lines 8884 and SR. Arrows show stomata

Characteristics of transgenic plants grown under the well-watered condition

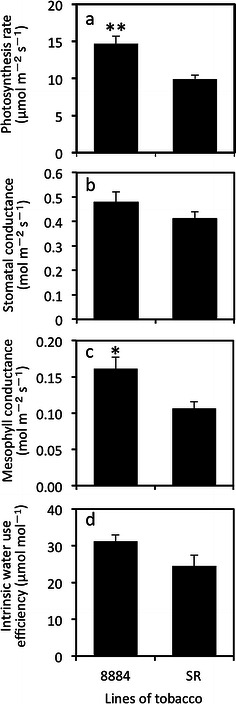

In comparison with the SR line, stem diameter of the 8884 line increased by 16 % (Table 1). The dry weight of the shoots in line 8884 was 62 % higher than that in the SR line. Although not significant, leaf area tended to be larger in line 8884. Transgenic plants showed a significantly higher photosynthesis rate (by 48 %), higher mesophyll conductance (by 52 %), and higher stomatal conductance (by 16 %) than those of the SR line (Fig. 3a–c). Intrinsic water use efficiency, which is calculated from the ratio of the photosynthesis rate to stomatal conductance (A/g s), was 27 % higher in line 8884 than that in line SR (Fig. 3d).

Table 1.

Characteristics of tobacco plants grown under the well-watered condition

| Characteristics | 8884 | SR |

|---|---|---|

| Leaf thickness (μm) | 313 ± 9 | 280 ± 36 |

| Mesophyll porosity (%) | 48 ± 2 | 49 ± 3 |

| S mes (m2 m−2) | 14.5 ± 1.3 | 13.2 ± 1.1 |

| S c (m2 m−2) | 8.8 ± 0.6 | 8.9 ± 0.4 |

| Stem diameter (mm) | 8.12 ± 0.27* | 7.02 ± 0.03 |

| Dry weight of shoot (g) | 11.4 ± 1.1* | 7.0 ± 0.9 |

| Leaf area (cm−2) | 13.1 ± 1.1 | 11.7 ± 6.0 |

| RWC (%) | 64.7 ± 0.9 | 68.2 ± 3.2 |

| Rubisco content (g m−2) | 1.57 ± 0.10 | 1.78 ± 0.20 |

Values are mean ± SE from four different plants (n = 4). Statistical analysis was done using an unpaired t test

* Means of transgenic plants are significantly different from the SR line (p < 0.05)

Fig. 3.

Gas exchange parameters in tobacco plants grown under the well-watered condition measured at ambient VPD. a Photosynthesis rate, b stomatal conductance, c mesophyll conductance, and d intrinsic water use efficiency, which is the ratio of the photosynthesis rate to stomatal conductance (A/g s). Values are mean ± SE of the two replicates from 4 to 5 different plants (n = 8–10). Statistical analysis was done using an unpaired t test. Asterisks above bars indicate that the means of transgenic plants are significantly different from the SR line (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01)

Photosynthesis under ambient and higher VPDs

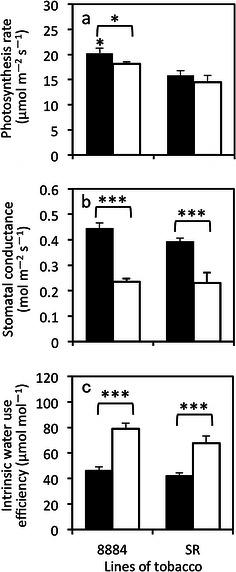

The photosynthesis rate of line 8884 was smaller at the higher VPD than the ambient VPD, but it was similar between ambient and higher VPDs for line SR (Fig. 4a). The photosynthesis rate was 10 % lower at the higher VPD in line 8884. On the other hand, stomatal conductance was significantly smaller at the higher VPD than ambient VPD in lines 8884 and SR, where the decrease was more in line 8884 (by 47 %) than that in line SR (by 41 %, Fig. 4b). Intrinsic water use efficiency was higher at the higher VPD, where the increase was greater in line 8884 (by 71 %) than that in line SR (by 60 %, Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Gas exchange parameters in tobacco plants grown under the well-watered condition, measured at ambient and higher VPD. a Photosynthesis rate, b stomatal conductance, c intrinsic water use efficiency, which is the ratio of the photosynthesis rate to stomatal conductance (A/g s). Values are mean ± SE of the two replicates from 3 to 5 different plants (n = 6–10). Filled bars and open bars are ambient VPD and higher VPD, respectively. Statistical analysis was done using an unpaired t test to determine the significance between lines and a paired t test between treatments. Asterisks above bars indicate that the means of transgenic plants are significantly different from the SR line in the same treatment, and asterisks above the arcs over the bars indicate significant differences between ambient and higher VPD in the same line (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001)

Under the same VPD, the photosynthesis rate of line 8884 was significantly higher (by 28 %) than that of line SR at ambient VPD. The photosynthesis rate of line 8884 was slightly higher than that of line SR at the higher VPD (by 25 %). The stomatal conductance of line 8884 was slightly higher than that of line SR at ambient VPD, although it was almost the same as that of line SR at the higher VPD. Intrinsic water use efficiency was almost the same value at ambient VPD. However, in the higher VPD condition, line 8884 had a slightly higher value (by 17 %) than that of line SR.

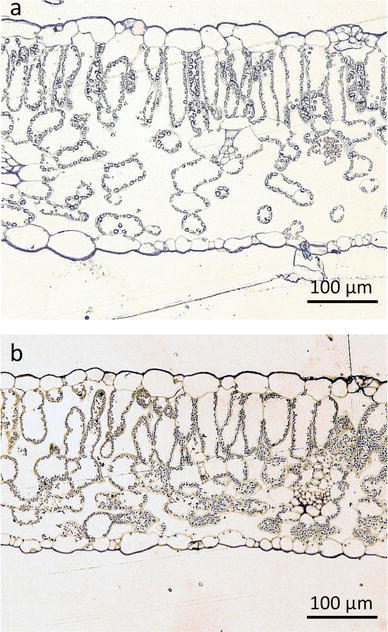

Rubisco content and mesophyll anatomy

Rubisco content was similar between lines SR and 8884 grown under the well-watered condition (Table 1). Leaf thickness, mesophyll porosity, S mes, and S c were similar between SR and 8884 lines (Table 1; Fig. 5). In both SR and 8884 lines, stomata were observed at epidermal cells on both the adaxial and abaxial sides of leaves (Fig. 5). Leaves have one layer of palisade tissue. Mesophyll cells were relatively loosely packed. Most of the surface of mesophyll cells facing intercellular air spaces was covered with chloroplasts.

Fig. 5.

Light micrographs of leaf sections of tobacco plants, taken at ×200 magnification. a Line 8884, b line SR

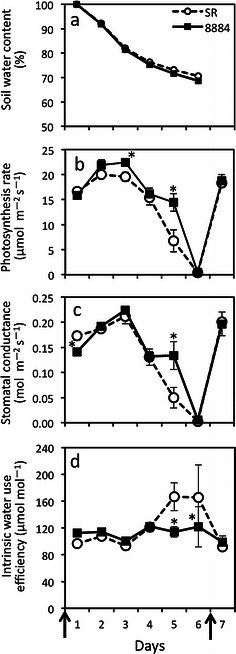

Photosynthesis response to the soil water deficit

Soil water content gradually decreased, reaching about 70 % at 6 days after the last irrigation for both SR and 8884 lines (Fig. 6a). The pattern of changes in the photosynthesis rate with time was similar to that of stomatal conductance for both SR and 8884 lines (Fig. 6b, c). The photosynthesis rate and stomatal conductance tended to be higher in line 8884 than those in line SR from 2 to 6 days after the last irrigation. At 5 days after the last irrigation, both the photosynthetic rate and stomatal conductance were significantly higher in line 8884 than those in line SR (113 and 169 % higher than that of SR, respectively). Line 8884 showed lower intrinsic water use efficiency than line SR 5 and 6 days after the last irrigation (Fig. 6d). On the 7th day, the photosynthesis rate and stomatal conductance recovered due to re-watering. There was no difference in the degree of recovery between lines 8884 and SR.

Fig. 6.

Changes in gas exchange parameters in tobacco plants under progressing soil water deficits and at re-watering. Plants were exposed to a water deficit for 1 month (irrigated once a week). Gas exchange measurements were performed from 1 to 5 days after the last irrigation date (left arrow) and at the re-watering date (right arrow). a Soil water content was estimated relative to pot weight at the first day from the last irrigation, b photosynthesis rate, c stomatal conductance, and d intrinsic water use efficiency, which is the ratio of the photosynthesis rate to stomatal conductance (A/g s). Values are mean ± SE from five different plants (n = 5). Statistical analysis was done using an unpaired t test. Asterisks above bars indicate that the means of transgenic plants are significantly different from the SR line on the same day (p < 0.05)

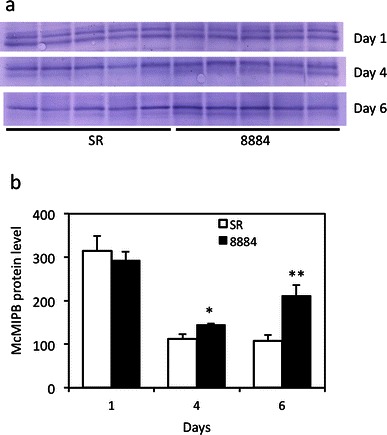

McMIPB protein levels changed with the soil water deficit treatment (Fig. 7a, b). As water stress became severe, McMIPB protein levels became higher in line 8884 than those in line SR. Plant height and stem diameter were similar between lines 8884 and SR when grown under the soil water deficit condition (Table 2). The dry weight of shoots under the soil water deficit condition was slightly higher in line 8884, while there was no change in the dry weight of roots (Table 2).

Fig. 7.

McMIPB protein levels of tobacco leaves grown under progressing soil water deficits. a McMIPB protein level and b intensity of McMIPB protein levels that were densitometrically quantified by Western analysis, where values are mean ± SE from five different plants (n = 5). Statistical analysis was done using an unpaired t test. Asterisks above bars indicate that the means of transgenic plants are significantly different from the SR line on the same day (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01)

Table 2.

Plant growth of tobacco plants grown under the water-stressed condition

| Plant growth | 8884 | SR |

|---|---|---|

| Plant height (cm) | 14.2 ± 2.2 | 14.6 ± 2.6 |

| Stem diameter (mm) | 4.66 ± 0.22 | 4.65 ± 0.11 |

| Dry weight of shoot (g) | 3.16 ± 0.12 | 3.04 ± 0.13 |

| Dry weight of root (g) | 0.62 ± 0.03 | 0.62 ± 0.02 |

Values are mean ± SE from five different plants (n = 5). Statistical analysis was done using an unpaired t test. The means of transgenic plants were not significantly different from the SR line (p > 0.05)

Discussion

Increased aquaporin levels enhanced photosynthesis and growth under the well-watered condition

Starting with the report of Terashima and Ono (2002), the number of studies concerning the CO2 permeability of aquaporin is now increasing (reviews by Flexas et al. 2012; Kaldenhoff et al. 2008; Katsuhara et al. 2008; Maurel 2007). The leaf photosynthesis rate in Eucalyptus trees was enhanced in transgenic plants overexpressing radish aquaporin RsPIP2;1 (Tsuchihira et al. 2010), supporting the role of aquaporin in leaf photosynthesis. In this study, McMIPB overexpressing tobacco plants grown under the well-watered condition increased mesophyll conductance (Fig. 3c), which suggest the CO2 permeability of aquaporin localized in mesophyll cells and chloroplasts (Fig. 2a, d). McMIPB levels and photosynthetic capacity were closely related (Figs. 1, 3). The increase in the photosynthesis rate in McMIPB overexpressing plants (Fig. 3a) was not due to changes in mesophyll anatomy and levels of carboxylation enzymes, because the Rubisco content and S c were similar between McMIPB overexpressing and control plants (Table 1). Therefore, we suggest that McMIPB in mesophyll cells and chloroplasts should enhance CO2 diffusion into chloroplasts of mesophyll cells and thus increase the photosynthetic rate. The localization of aquaporin in plasma membranes of mesophyll cells and chloroplasts was shown for tobacco aquaporin NtAQP1, which had CO2 permeability and enhanced CO2 diffusion and photosynthesis rate (Uehlein et al. 2008).

CO2 permeability differs among aquaporins. Tobacco aquaporin NtAQP1 enhanced CO2 diffusion, whereas NtPIP2;1 did not (Otto et al. 2010). CO2 permeability may not depend on the sub-type of aquaporin (PIP1 or PIP2, Katsuhara, unpublished data), while the co-expression of PIP2 with PIP1 may enhance the channel activity of PIP1. The different combinations of PIP1 and PIP2 in the subunits of aquaporin tetramers may affect the CO2 permeability of aquaporin (Flexas et al. 2012). McMIPB is classified as PIP1, with possible partners of PIP2 aquaporin McMIPC or McMIPE in the subunits of tetramers.

Stem diameter and dry weight in McMIPB overexpressing tobacco was significantly higher than those of control plants (Table 1), possibly due to increases in the leaf photosynthetic capacity. Plant heights were shown to drastically increase in tobacco plants overexpressing A. thaliana aquaporin PIP1b (Aharon et al. 2003), although NtAQP1 overexpressing tobacco plants did not show significant changes in growth over control plants (Flexas et al. 2006). Differences between studies may be due to exogenous or endogenous aquaporin, or may be partly affected by the plant size. In the present study, we used small plants with a small number of leaves with large leaf areas, where shoot growth was largely determined by leaf growth. Increases in leaf photosynthesis may have directly enhanced the growth of the whole plant through enhancements in leaf growth in the present study.

Increased aquaporin levels affect the stomatal response to a water deficit

Both transgenic and control plants exposed to higher VPD showed a drastic decline in g s (Fig. 4b), which is in line with previous reports that demonstrated declines in g s at higher VPD for non-transgenic plants (Day 2000; Shirke and Pathre 2004; Warren 2008). We should note that an increase in leaf temperature by 3 °C at the higher VPD may have partly affected the stomatal response to higher VPD. Declines in g s from ambient to higher VPD were more significant in overexpressing McMIPB plants. Declines in the transpiration rate from ambient to higher VPD were also larger in overexpressing McMIPB plants (data not shown). These results suggest that the sensitivity of g s to temporal atmospheric water deficits may be higher in overexpressing McMIPB plants than that of control plants, which may moderate water loss from the leaves and increase water use efficiency (Fig. 3d).

On the other hand, when exposed to a soil water deficit, declines in the photosynthesis rate and stomatal conductance with time were lower in overexpressing McMIPB plants than those in control plants, at 5 days in particular (Fig. 6b, c). Higher McMIPB levels were obtained at 4 days in overexpressing McMIPB plants than those in control plants (Fig. 7b). These results suggest that a high aquaporin level relates to stomatal regulation to a soil water deficit, which induces less sensitivity of stomata to a soil water deficit, resulting in lower water use efficiency in overexpressing McMIPB plants (Fig. 6d). Stomatal aperture may be affected by aquaporin level via changes in turgor pressure of guard cells. The transpiration rate was much higher in overexpressing McMIPB plants at 5 days (data not shown), which is in line with results by Siefritza et al. (2002) in which the transpiration rate of control plants was larger than NtAQP1-antisense tobacco plants under drought conditions.

The results of a temporal atmospheric water deficit and prolonged soil water deficit suggest that the effect of aquaporin on stomatal sensitivity is different between atmospheric and soil water deficit. Warren (2008) showed that g s was decreased by both atmospheric and soil water deficits, while g m was decreased by a soil water deficit only. We obtained similar g m between higher and ambient VPD for both overexpressed and control plants (data not shown), which supports the above results by Warren (2008). The lower sensitivity of g s to a soil water deficit in overexpressing McMIPB plants may compensate partly for the decrease in CO2 supply by decreasing g m. Although the mechanisms are unclear, there may be a co-relationship between g s and g m through aquaporin, which may regulate the balance of CO2 supply to chloroplasts and water loss from leaves.

Some aquaporins are highly expressed in guard cells (Fraysse et al. 2005; Kaldenhoff et al. 1995; Otto and Kaldenhoff 2000; Sun et al. 2007). Tobacco aquaporin NtAQP1 was shown to localize in chloroplasts of guard cells, and this NtAQP1 has CO2 permeability (Uehlein et al. 2008). In this study, the McMIPB signal strongly appeared in the chloroplasts of guard cells in overexpressing McMIPB plants (Fig. 2), where McMIPB aquaporin should have CO2 permeability. These aquaporins may affect stomatal regulation, as well as decrease the resistance of photosynthetic pathways due to their CO2 permeability in guard cells.

The dry weight of shoots exposed to a soil water deficit was slightly higher in overexpressing McMIPB plants, while there was no change in the dry weight of roots (Table 2). These results support the report of Katsuhara et al. (2003), which shows a higher shoot/root ratio in overexpressing HvPIP2;1 rice plants under salt stress. The McMIPB aquaporin in the present study may play a role in water transport; the high hydraulic conductivity raised by aquaporin in the roots may support water transport with a low root mass in transgenic plants (Katsuhara et al. 2003).

Relationship between mesophyll anatomy and aquaporin expression

Hanba et al. (2004) demonstrated that barley aquaporin HvPIP2;1 overexpressing rice plants showed anatomical changes (S mes, S c, mesophyll porosity, stomatal density, stomatal size). Tsuchihira et al. (2010) reported changes in the leaf morphology of Eucalyptus trees overexpressing RsPIP2;1. However, Flexas et al. (2006) reported that tobacco endogenous aquaporin NtAQP1 overexpressing tobacco plants showed no anatomical changes, and argued that anatomical changes may be due to the transformation by an exogenous aquaporin. In Table 1 and Fig. 5, overexpressing McMIPB tobacco plants showed no significant change in leaf thickness, mesophyll porosity, S mes, or S c. We suggest that anatomical changes in aquaporin overexpressing plants may be indirect ones, which may be the result of plant acclimation to some physiological changes such as water relations in transgenic plants. If aquaporin causes water stress in plants, leaf anatomy would change accordingly.

Conclusions

The higher photosynthesis rate (by 48 %) and mesophyll conductance (by 52 %) in transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing ice plant aquaporin McMIPB than those in control plants under the well-watered growth condition suggests the CO2 permeability of McMIPB localized in mesophyll cells and chloroplasts. McMIPB should be the fourth aquaporin candidate for enhancing CO2 diffusion in leaves. Plants overexpressing aquaporin have low sensitivities to photosynthesis and g s to a prolonged soil water deficit, but have slightly high sensitivities to photosynthesis and g s to a temporal higher VPD, which is a new finding. These results suggest that McMIPB may be effective in compensating for the decrease in CO2 supply via stomatal regulation under a soil water deficit, but not so under a high VPD. Extensive studies will be needed to understand the role of aquaporin in photosynthesis, particularly in CO2 and water diffusion via mesophyll and stomatal regulation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Plant Innovation Center, Japan Tobacco Inc. for generating transgenic tobacco plants and the tobacco SR line used in this study. We are grateful to Professor Masayoshi Maeshima, Dr. Ayako Tsuchihira (Nagoya University), and Dr. Yusaku Yasuno (Kyoto Institute of Technology) for their helpful advice and technical support. We would like to thank the Center for Ecological Research, Kyoto University, for assisting with the measurements of carbon isotope ratios.

Abbreviations

- gs

Stomatal CO2 conductance

- gm

Mesophyll CO2 conductance

- McMIP

Aquaporin, which is an ice plant (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L.) membrane intrinsic protein

- McMIPB

Aquaporin detected by the McMIPB antibody

- Smes

Surface area of mesophyll cells facing intercellular airspaces

- Sc

Surface area of chloroplasts facing intercellular airspaces

- PIP

Aquaporin, which is a plasma membrane intrinsic protein

- RWC

Relative water content

- VPD

Vapor pressure deficit

References

- Adams P, Nelson DE, Yamada S, Chmara W, Jensen RG, Bohnent HJ, Griffiths H. Growth and development of Mesembryanthemum crystallinum (Aizoaceae) New Phytol. 1998;138:171–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1998.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharon R, Shahak Y, Wininger S, Bendov R, Kapulnik Y, Galili G. Overexpression of a plasma membrane aquaporin in transgenic tobacco improves plant vigor under favorable growth conditions but not under drought or salt stress. Plant Cell. 2003;15:439–447. doi: 10.1105/tpc.009225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour MM, Warren CR, Farquhar GD, Forrester G, Brown H. Variability in mesophyll conductance between barley genotypes, and effects on transpiration efficiency and carbon isotope discrimination. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:1176–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves MM, Flexas J, Pinheiro C. Photosynthesis under drought and salt stress: regulation mechanisms from whole plant to cell. Ann Bot. 2009;103:551–560. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day EM. Influence of temperature and leaf-to-air vapor pressure deficit on net photosynthesis and stomatal conductance in red spruce (Picea rubens) Tree Physiol. 2000;20:57–63. doi: 10.1093/treephys/20.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Ribas-Carbó M, Hanson DT, Bota J, Otto B, Cifre J, McDowell N, Medrano H, Kaldenhoff R. Tobacco aquaporin NtAQP1 is involved in mesophyll conductance to CO2 in vivo. Plant J. 2006;48:427–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Barón M, Bota J, Ducruet J-M, Gallé A, Galmés J, Jiménez M, Pou A, Ribas-Carbó M, Sajnani C, Tomàs M, Medrano H. Photosynthesis limitations during water stress acclimation and recovery in the drought-adapted Vitis hybrid Richter-110 (V. berlandieri × V. rupestris) J Exp Bot. 2009;60:2361–2377. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Barbour MM, Brendel O, Cabreraa HM, Carriquía M, Díaz-Espejof A, Douthe C, Dreyer E, Ferrio JP, Gago J, Gallé A, Galmés J, Kodama N, Medrano H, Niinemets Ü, Peguero-Pina JJ, Pou A, Ribas-Carbó M, Tomás M, Tosens T, Warren CR. Mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2: an unappreciated central player in photosynthesis. Plant Sci. 2012;193–194:70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraysse LC, Wells B, McCann MC, Kjellbom P. Specific plasma membrane aquaporins of the PIP1 subfamily are expressed in sieve elements and guard cells. Biol Cell. 2005;97:519–534. doi: 10.1042/BC20040122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanba YT, Miyazawa S-I, Terashima I. The influence of leaf thickness on the CO2 transfer conductance and leaf stable carbon isotope ratio. Funct Ecol. 1999;13:632–639. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2435.1999.00364.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanba YT, Kogami H, Terashima I. The effect of growth irradiance on leaf anatomy and photosynthesis in Acer species differing in light adaptation. Plant Cell Environ. 2002;25:1021–1030. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00881.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanba YT, Shibasaka M, Hayashi Y, Hayakawa T, Kasamo K, Terashima I, Katsuhara M. Overexpression of the barley aquaporin HvPIP2;1 increases internal CO2 conductance and CO2 assimilation in the leaves of transgenic rice plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:521–529. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckwolf M, Pater D, Hanson TD, Kaldenhoff R. The Arabidopsis thaliana aquaporin AtPIP1;2 is a physiologically relevant CO2 transport facilitator. Plant J. 2011;67:795–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsch RB, Fry JE, Hoffmann NL, Eichholtz D, Rogers SG, Fraley RT. A simple and general method for transferring genes into plants. Science. 1985;227:1229–1231. doi: 10.1126/science.227.4691.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldenhoff R, Kolling A, Meyers J, Karmann U, Ruppel G, Richter G. The blue light-responsive AthH2 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana is primarily expressed in expanding as well as in differentiating cells and encodes a putative channel protein of the plasmalemma. Plant J. 1995;7:87–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1995.07010087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldenhoff R, Ribas-Carbó M, Flexas J, Lovisolo C, Heckwolf M, Uehlein N. Aquaporins and plant water balance. Plant Cell Environ. 2008;31:658–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuhara M, Akiyama Y, Koshio K, Shibasaka M, Kasamo K. Functional analysis of water channels in barley roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:885–893. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuhara M, Koshio K, Shibasaka M, Hayashi Y, Hayakawa T, Kasamo K. Over-expression of a barley aquaporin increased the shoot/root ratio and raised salt sensitivity in transgenic rice plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44:1378–1383. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuhara M, Hanba YT, Shiratake K, Maeshima M. Expanding roles of plant aquaporins in plasma membranes and cell organelles. Funct Plant Biol. 2008;35:1–14. doi: 10.1071/FP07130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirch H–H, Vera-Estrella R, Golldack D, Quigley F, Michalowski CB, Barkla BJ, Bohnert HJ. Expression of water channel proteins in Mesembryanthemum crystallinum. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:111–124. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama N, Cousin A, Tu KP, Barbour MM. Spatial variation in photosynthetic CO2 carbon and oxygen isotope discrimination along leaves of the monocot triticale (Triticum × Secale) relates to mesophyll conductance and the Péclet effect. Plant Cell Environ. 2011;34:1548–1562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian H-L, Yu X, Ye Q, Ding X-S, Kitagawa Y, Kwak S-S, Su W-A, Tang Z-C. The role of aquaporin RWC3 in drought avoidance in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:481–489. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Mae T, Ohira K. Enzymic properties of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase purified from rice leaves. Plant Physiol. 1985;79:57–61. doi: 10.1104/pp.79.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel C. Plant aquaporins: novel functions and regulation properties. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2227–2236. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto B, Kaldenhoff R. Cell-specific expression of the mercury-insensitive plasma-membrane aquaporin NtAQP1 from Nicotiana tabacum. Planta. 2000;211:167–172. doi: 10.1007/s004250000275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto B, Uehlein N, Sdorra S, Fischer M, Ayaz M, Belastegui-Macadam X, Heckwolf M, Lachnit M, Pede N, Priem N, Reinhard A, Siegfart S, Urban M, Kaldenhoff R. Aquaporin tetramer composition modifies the function of tobacco aquaporins. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:31253–31260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.115881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scartazza A, Lauteri M, Guido MC, Brugnoli E. Carbon isotope discrimination in leaf and stem sugars, water use efficiency and mesophyll conductance during different developmental stages in rice subjected to drought. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1998;25:489–498. doi: 10.1071/PP98017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shirke AP, Pathre VU. Influence of leaf-to-air vapour pressure deficit (VPD) on the biochemistry and physiology of photosynthesis in Prosopis juliflora. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:2111–2120. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siefritza F, Tyreeb MT, Lovisoloc C, Schubert A, Kaldenhoff R. PIP1 plasma membrane aquaporins in tobacco from cellular effects to function in plants. Plant Cell. 2002;14:869–876. doi: 10.1105/tpc.000901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M-H, Xu W, Zhu Y-F, Su W-A, Tang Z-C. A simple method for in situ hybridization to RNA in guard cells of Vicia faba L.: the expression of aquaporins in guard cells. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2007;19:129–135. doi: 10.1007/BF02772155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tazoe Y, von Caemmerer S, Badger MR, Evans JR. Light and CO2 do not affect the mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion in wheat leaves. J Exp Bot. 2009;60:2291–2301. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazoe Y, von Caemmerer S, Estavillo GM, Evans JR. Using tunable diode laser spectroscopy to measure carbon isotope discrimination and mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion dynamically at different CO2 concentrations. Plant Cell Environ. 2011;34:580–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I, Ono K. Effects of HgCl2 on CO2 dependence of leaf photosynthesis: evidence indicating involvement of aquaporins in CO2 diffusion across the plasma membrane. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43:70–78. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcf001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I, Hanba YT, Tazoe Y, Vyas P, Yano S. Irradiance and phenotype: comparative eco-development of sun and shade leaves in relation to photosynthetic CO2 diffusion. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:343–354. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I, Hanba Y, Tholen D, Niinemets Ü. Leaf functional anatomy in relation to photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:108–116. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.165472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchihira A, Hanba YT, Kato N, Doi T, Kawazu T, Maeshima M. Effect of overexpression of radish plasma membrane aquaporins on water-use efficiency, photosynthesis and growth of Eucalyptus trees. Tree Physiol. 2010;30:417–430. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpp127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehlein N, Lovisolo C, Siefritz F, Kaldenhoff R. The tobacco aquaporin NtAQP1 is a membrane CO2 pore with physiological functions. Nature. 2003;425:734–737. doi: 10.1038/nature02027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehlein N, Otto B, Hanson DT, Fischer M, McDowell N, Kaldenhoff R. Function of Nicotiana tabacum aquaporins as chloroplast gas pores challenges the concept of membrane CO2 permeability. Plant Cell. 2008;20:648–657. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Evans JR. Determination of the average partial pressure of CO2 in chloroplasts from leaves of several C3 species. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1991;18:287–305. doi: 10.1071/PP9910287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warren CR. Soil water deficits decrease the mesophyll conductance to CO2 transfer but atmospheric water deficits do not. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:327–334. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada S, Katsuhara M, Kelly WB, Michalowski CB, Bohnert HJ. A family of transcripts encoding water channel proteins: tissue-specific expression in the common ice plant. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1129–1142. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.8.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada S, Komori T, Myers PN, Kuwata S, Kubo T, Imaseki H. Expression of plasma membrane water channel genes under water stress in Nicotiana excelsior. Plant Cell Physiol. 1997;38:1226–1231. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Noguchi K, Hanba YT, Terashima I. Effects of internal conductance on the temperature dependence of the photosynthetic rate in spinach leaves from contrasting growth temperatures. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47:1069–1080. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]