Abstract

Purpose

To compare demographic characteristics and predictors of survival of rural residents diagnosed with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) with those of urban residents.

Methods

Florida surveillance data for people diagnosed with AIDS during 1993–2007 were merged with 2000 Census data using ZIP code tabulation areas (ZCTA). Rural status was classified based on the ZCTA’s rural-urban commuting area classification. Survival rates were compared between rural and urban areas using survival curves and Cox proportional hazards models controlling for demographic, clinical, and area-level socioeconomic and health care access factors.

Findings

Of the 73,590 people diagnosed with AIDS, 1,991 (2.7%) resided in rural areas. People in the most recent rural cohorts were more likely than those in earlier cohorts to be female, non-Hispanic black, older, and have a reported transmission mode of heterosexual sex. There were no statistically significant differences in the 3-, 5-, or 10-year survival rates between rural and urban residents. Older age at the time of diagnosis, diagnosis during the 1993–1995 period, other/unknown transmission mode, and lower CD4 count/percent categories were associated with lower survival in both rural and urban areas. In urban areas only, being non-Hispanic black or Hispanic, being US born, more poverty, less community social support, and lower physician density were also associated with lower survival.

Conclusions

In rural Florida, the demographic characteristics of people diagnosed with AIDS have been changing, which may necessitate modifications in the delivery of AIDS-related services. Rural residents diagnosed with AIDS did not have a significant survival disadvantage relative to urban residents.

Keywords: access to care, AIDS, mortality, rural health, rural population

Although the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) epidemic was first recognized in urban areas of the United States, at the end of 2009 an estimated 52,195 people residing in rural areas (ie, non-metropolitan areas with population < 50,000) were living with HIV infection, including an estimated 29,369 with AIDS.1 In 2010, 6.7% of all reported HIV cases and 6.7% of all reported AIDS cases in the US were from rural areas. The rural South has been particularly affected by AIDS and had the greatest number of rural AIDS cases and the highest rural AIDS case rate in 2006.2

Because of the complexities of treating HIV/AIDS, rural residents may have more barriers than urban residents in accessing quality HIV/AIDS care and adhering to treatment, which in turn may adversely affect survival. One barrier is that the availability of health care providers, especially those providing specialty care, tends to be more limited in rural areas.3 Many people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), therefore, travel to distant urban areas to obtain care. According to the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Survey (HCSUS), a national representative survey of PLWHA conducted in 1996, 60% of rural residents obtained all their HIV care in urban areas, and an additional 12% obtained care in both rural and urban settings.4 The median travel time for rural residents obtaining their care in urban areas was 60 minutes (vs 20 minutes for urban residents), and 28.8% (vs 7.6% for urban residents) reported delaying care due to the time it took for them to reach their usual source of HIV care.4 A 2004 survey of HIV service providers in rural counties of southern states reported that the average distance for clients to travel for HIV treatment was 50 miles, and travel distance was reported as a significant barrier to treatment.5 Results of a focus group study among rural women suggested that accessing care may be particularly problematic when the cost of gasoline increases.6

In addition to travel barriers, the quality of care available in rural areas may not be as high as that in urban areas because rural clinicians tend to see fewer patients with HIV than their urban counterparts. Primary care physician experience has been found to be a predictor of survival among PLWHA.7 Hospital experience has also been found to be predictive of outcomes among AIDS patients.8,9 The 1996 HCSUS study found that people obtaining care in rural clinics were less likely than those obtaining care in urban clinics to receive highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) or prophylactic medications.10

A third potential barrier in some rural areas is fragmented HIV services due to fewer full-time AIDS service organizations than in urban areas.11 Rural areas may be receiving less Ryan White funding per patient relative to urban areas,12 and limited social service benefits and support are associated with less adherence to antiretroviral therapy.13 Furthermore, HIV-related stigma may be more pronounced in rural areas, posing an additional barrier to treatment.14 In one study conducted in the late 1990s in the rural southeast, about 10% of PLWHA reported being refused care by a health care provider.15 Finally, concerns that their confidentiality cannot be maintained in small, local clinics drive some rural PLWHA to seek care in distant urban areas.5,16

There have been relatively few studies comparing outcomes among PLWHA in rural areas with those in urban areas in the United States, and the results have been inconsistent. A study of Veterans Administration patients beginning HIV care during 1998–2006 found that rural residence was associated with both later entry into care and lower survival.17 However, once later entry into care was adjusted for, the difference in survival was no longer statistically significant. A study of patients receiving HIV care during 1995–2005 at a multisite New England medical practice found that although rural and urban patients presented with similar CD4 counts, rural patients had a higher risk of mortality.18 However, a study of patients receiving care during 1996–2006 in rural and urban HIV specialty clinics in Vermont found that survival times were similar for urban and rural patients.19 Only one population-based study was identified. It found that rural HIV cases reported to the South Carolina HIV surveillance system during 2001–2005 were more likely to have an AIDS diagnosis within 12 months of the first positive HIV test than cases from urban areas after adjusting for gender, age, race and mode of exposure.20 Our literature search did not reveal any population-based studies comparing survival between rural and urban areas in the United States.

To address this gap, we sought to describe the characteristics of people diagnosed with AIDS who resided in rural Florida and compare their survival with that of urban residents diagnosed with AIDS in Florida. Further, we sought to compare predictors of AIDS survival in rural with those in urban Florida.

METHODS

Ascertainment of Cases and Survival Status

Records of Florida residents diagnosed with AIDS during 1993–2007 were obtained from the Florida Department of Health Enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System (eHARS). AIDS cases met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) AIDS case definition (had a documented positive confirmatory HIV test and CD4 lymphocyte count < 200 cells/µL or CD4 percentage of total lymphocytes < 14 at time of diagnosis, or had an AIDS defining condition).21 The analysis used AIDS diagnoses and not HIV diagnoses that had not progressed to AIDS because HIV surveillance began in July 1997 and the HIV diagnosis date in the surveillance system has been found to be unreliable for those without AIDS. This problem is due to some people having a positive HIV test after HIV became reportable but who were diagnosed prior to 1997. For this study, AIDS diagnoses were divided into 5 cohorts by 3-year diagnosis period (1993–1995, 1996–1998, 1999–2001, 2002–2004, 2005–2007) to capture time periods before HAART, during early HAART implementation, and after HAART became widely available.

Deaths through 2007 were ascertained by linking eHARS records with death certificate records from the Florida Department of Health Office of Vital Statistics, the Social Security Administration’s Death Master File, and the National Death Index. The details of this linkage process have been previously published.22 Any person alive as of December 31, 2007, was censored. An event was a death from any cause and not necessarily due to HIV as the underlying cause of death, because HIV/AIDS is sometimes not correctly recorded as the cause of death,23 because the underlying cause of death was missing from over 20% of records, and to be consistent with other studies assessing survival following a diagnosis of HIV/AIDS.24–34

The following individual-level variables were available in the eHARS dataset: zone improvement plan (ZIP) code and county of residence at time of AIDS diagnosis, month and year of AIDS diagnosis and death, country of birth, age at AIDS diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, HIV transmission mode, and if diagnosis was at a correctional facility. The CD4 lymphocyte count/percents were considered if measured within 3 months of the AIDS diagnosis date. Among those records that had a CD4 count and not a percentage or vice versa, the range of available counts and percentages were divided into quartiles, and the record was assigned to the lowest CD4 lymphocyte count/percent category. If there was no CD4 lymphocyte count/percentage within 3 months of the AIDS diagnosis and the person had been diagnosed with an AIDS-defining illness at the time of diagnosis, the person was classified into the category of having an AIDS-defining illness only. Race/ethnicity was classified into 4 groups: non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, and all other racial groups (eg, Asian, American Indian, multiracial, etc.). For HIV/AIDS transmission mode, people with a combined reported transmission mode of men who have sex with men (MSM) and injection drug user (IDU) were grouped with people with the IDU transmission mode.

Zip Code Tabulation Areas SES Data From US Census

Area-level socioeconomic (SES) data were obtained from the 2000 US Census and linked using the ZIP code tabulation area (ZCTA) because ZIP codes were not available in the 2000 US Census.35 A ZCTA approximates a ZIP code and is built by aggregating the 2000 US Census blocks based on the ZIP code of addresses in these blocks into a ZCTA. Records of diagnosed AIDS cases whose ZIP code was missing or non-existing (n=693) as well as those for which the ZIP code could not be converted to a ZCTA (n=34) were excluded from the analysis.

The 13 specific variables that were downloaded from the 2000 US Census were related to the broad sub-domains of poverty: income and wealth; employment; housing and crowding; education; occupation; and transportation and were chosen because they have been the most commonly used SES indicators in research studies.36–40 Because of the large number of these variables, 3 socioeconomic indices (poverty index, affluence index, and the Townsend-like index) were used in place of the individual variables. These indices were developed and assessed as to their predictive validity for AIDS incidence using reliability analysis, factor analysis with principal component factorization, and structural equation modeling.41 The Townsend-like index was named after the Townsend Index developed in England because of the similarity of the factors comprising it to those of the original Townsend Index.42 The Townsend–like index includes the percentage of households with no access to a car, households with more than 1 person per room, households living in a rented home and people ≥ 16 years old who are unemployed in the ZCTA. The poverty index includes the percentage of individuals with less than a 12th grade education, income disparity (defined as the ratio of % of low income to % of high income), and the percentage of households with incomes below the poverty line and with annual income < $15,000 in the ZCTA. The affluence index includes the median household income in 1999, the percentage of households with annual income ≥ $150,000, the percentage of persons aged ≥ 25 years with a graduate or professional degree, the percentage of persons employed in the predominantly high working class occupations, and the percentage of owner-occupied homes worth ≥ $300,000 in the ZCTA. It was reverse coded so that its direction is the same as the other 2 indices and is thus reported as lack of affluence.

Area health care access variables were obtained from the Health Resources and Services Administration Area Resource File (2007 Release).43 The average number of short-term general hospitals per 100 square miles during the 1995–2005 period and the average number of actively practicing medical doctors and doctors of osteopathy per 100 square miles during 1994–1996 were calculated for each county. The numbers of hospitals and physicians per square mile were considered because other studies indicated that transportation is a barrier to obtaining health care among people living with HIV infection.5,6

Social support was based on the percentage of adults in each county who responded in the 2007 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System that they always or usually receive the social and emotional support they need. The homicide rates were the 10-year average of age-adjusted homicide rates per 100,000 population during 1996–2005. Social support and homicide data were obtained from the Florida Department of Health Office of Health Statistics and Assessment Florida Community Health Assessment Resource Tool Set (CHARTS).44

Rural-Urban Classification

Florida ZCTAs were divided into rural and urban areas using the ZIP code approximation of the Version 2.0 Rural-Urban Categorization (RUCA) data codes developed at the University of Washington WWAMI Rural Research Center.45,46 The RUCA codes were developed using the US Census Bureau urbanized areas and urban clusters as well as urban commuting patterns. There are 33 RUCA codes that can be categorized several different ways. Categorization C was used in this analysis because it classified the codes into only 2 categories (rural and urban), with the rural category being restricted to small and large rural towns/cities. One Florida ZCTA classified as rural using RUCA was responsible for 537 (30.7%) of all rural cases. This ZCTA was for Key West (2000 population = 24,649),47 which has a relatively large gay community and is a popular tourist destination. Over 75% of all Key West cases reported a HIV transmission mode of MSM compared to 25.3% among other rural cases. Relative to the other rural areas in Florida, it has a high concentration of physicians. Because this area’s characteristics are so different from that of other rural areas in Florida, the cases diagnosed in this ZCTA were excluded from the analysis so that the rural results would be more generalizable to other rural areas. Cases diagnosed at correctional facilities were excluded from the analysis because their address of AIDS diagnosis was the corrections facility and not their permanent home address. These 3,095 cases (4.2% of all cases) made up 2.5% of urban ZCTA cases and 39% of rural ZCTA cases because correctional facilities in Florida tend to be built in rural areas.

ANALYSIS

Associations between rural/urban status and potential predictors of survival were tested using the chi-square test for categorical variables and 2 sample Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests for continuous variables. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the rural and urban areas were generated, and curves were also examined to determine if the assumption of proportional hazards required for Cox regression models was violated.48 Because the assumption of proportional hazards was violated in models comparing rural and urban areas and in order to compare factors associated with survival in rural and urban areas, the models for rural and urban areas were considered separately. Three sets of 2-level (ie, level I: individual, and level II: community) Cox proportional hazards models were performed. The first was unadjusted (producing crude hazards ratios), the second adjusted for all variables and the third adjusted only for those that were significant in the model (manual backward selection of variables based on a P value ≥ .05). Area-level SES and health care access were both assessed as community-level variables (level II variables) by considering the clustering of cases within ZCTAs.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina; 2002–2008).49 The Florida Department of Health Institutional Review Board approved the study, and the Florida International University deemed this study exempt from Institutional Review Board review.

RESULTS

In Florida, there were 73,590 people diagnosed with AIDS from 1993–2007 who met the inclusion criteria. Of these 1,991 (2.7%) were reported from rural areas. In later rural cohorts relative to earlier ones, there were higher proportions of persons who were female, non-Hispanic black, diagnosed in the 40- to 59-year-old age group, and who reported HIV transmission mode of heterosexual sex (Table 1). There were also smaller proportions of non-Hispanic whites, people younger than age 20 at the time of diagnosis, and people in the lowest 2 CD4 count/CD4 percent categories. The 3-year survival rate increased appreciably, particularly from the 1993–1995 cohort (49.9%) to the 1996–1998 cohort (73.5%).

Table 1.

Individual-level characteristics of people diagnosed with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in rural areas by year of diagnosis, Florida, 1993–2007, n=1991

| Characteristics | Diagnosed 1993–1995 n (%) |

Diagnosed 1996–1998 n (%) |

Diagnosed 1999–2001 n (%) |

Diagnosed 2002–2004 n (%) |

Diagnosed 2005–2007 n (%) |

P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 95 (23.9) | 126 (31.3) | 115 (28.7) | 124 (32.5) | 133 (32.6) | |

| Male | 302 (76.1) | 277 (68.7) | 286 (71.3) | 258 (67.5) | 275 (67.4) | .04 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 199 (50.1) | 235 (58.3) | 241 (60.1) | 220 (57.6) | 238 (58.3) | |

| Hispanic | 37 (9.3) | 38 (9.4) | 41 (10.2) | 51 (13.4) | 44 (10.8) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 152 (38.3) | 124 (30.8) | 111 (27.7) | 102 (26.7) | 113 (27.7) | |

| Other | 9 (2.3) | 6 (1.5) | 8 (2.0) | 9 (2.4) | 13 (3.2) | .03 |

| Age group at diagnosis | ||||||

| < 20 years | 9 (2.3) | 11 (2.7) | 4 (1.0) | 5 (1.3) | 3 (0.7) | |

| 20–39 years | 247 (62.2) | 212 (52.6) | 197 (49.1) | 174 (45.6) | 169 (41.4) | |

| 40–59 years | 113 (28.5) | 153 (38.0) | 170 (42.4) | 173 (45.3) | 211 (51.7) | |

| 60 years or older | 28 (7.1) | 27 (6.7) | 30 (7.5) | 30 (7.9) | 25 (6.1) | <.0001 |

| Place of birth | ||||||

| United States | 369 (93.0) | 373 (92.6) | 371 (92.5) | 338 (88.5) | 365 (89.5) | |

| Not United States | 28 (7.1) | 30 (7.4) | 30 (7.5) | 44 (11.5) | 43 (10.5) | .08 |

| Mode of transmission | ||||||

| Men who have sex with men | 117 (29.5) | 94 (23.3) | 99 (24.7) | 91 (23.8) | 103 (25.3) | |

| Injection drug useb | 100 (25.2) | 80 (19.9) | 88 (22.0) | 67 (17.5) | 80 (19.6) | |

| Heterosexual | 119 (30.0) | 155 (38.5) | 148 (36.9) | 166 (43.5) | 174 (42.7) | |

| Other/unknown | 61 (15.4) | 74 (18.4) | 66 (16.5) | 58 (15.2) | 51 (12.5) | .01 |

| Lowest CD4 count/µl or CD4 percent categoryc | ||||||

| < 20 or < 3% | 96 (24.3) | 85 (21.1) | 73 (18.3) | 61 (16.1) | 71 (17.5) | |

| 20–53 or 3%–5% | 80 (20.3) | 67 (16.6) | 76 (19.1) | 80 (21.1) | 58 (14.3) | |

| 54–110 or 6%–8% | 57 (14.4) | 80 (19.9) | 71 (17.8) | 66 (17.4) | 75 (18.5) | |

| 111–161 or 9%–11% | 58 (14.7) | 57 (14.1) | 66 (16.5) | 67 (17.6) | 80 (19.8) | |

| 162–199 or 12%–13% | 40 (10.1) | 41 (10.2) | 54 (13.5) | 58 (15.3) | 85 (21.0) | |

| Met case definition with AIDS defining condition only or unknown CD4 count/% | 64 (16.2) | 73 (18.1) | 59 (14.8) | 48 (12.6) | 36 (8.9) | <.0001 |

| Three-year survival | ||||||

| Alive | 198 (49.9) | 296 (73.5) | 310 (77.3) | 290 (75.9) | Not | |

| Dead | 199 (50.1) | 107 (26.6) | 91 (22.7) | 92 (24.1) | Applicable | <.0001 |

P values from chi-square tests except for CD4 count and percentage which were calculated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Includes men who have sex with men who also reported injection drug use.

For CD4 count/percent category there were 9 missing values (0.5% of total).

The proportion of diagnoses from rural areas did increase somewhat over time from 2.0% (397 of 20,123) in the 1993–1995 cohort to 3.4% (408 of 11,892) in the 2005–2007 cohort. This was principally due to the number of urban cases decreasing (Table 2). People diagnosed with AIDS who resided in rural areas were significantly more likely than those residing in urban areas to have been diagnosed during later cohorts, be non-Hispanic black and be US born (Table 2). They were significantly less likely to be Hispanic and have a reported transmission mode of MSM. There was no difference between rural and urban areas in the median age at the time of AIDS diagnosis or in the distribution of CD4 count/percent categories. People living in rural areas were more likely to live in a ZCTA with a higher poverty index and higher lack of affluence index but with a lower (more favorable) Townsend-like index (Table 2). Thus, depending on how socioeconomic status was measured, AIDS cases occurring in rural areas were either more exposed or less exposed to socioeconomic deprivation than those in urban areas. Diagnoses from rural areas were more likely to be among residents of counties with a low density of doctors and hospitals, lower murder rates, and lower reported emotional and social support.

Table 2.

Comparison of individual-level characteristics, community-level characteristics, and survival of people diagnosed with acquired immunodeficiency virus (AIDS), by rural/urban status, Florida, 1993–2007

| Characteristics | Total (n=73,590) n (%) |

Rural Total (n=1,991) n (%) |

Urban Total (n=71,599) n (%) |

P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-level characteristics | ||||

| Year of AIDS report | ||||

| 1993–1995 | 20,123 (27.3) | 397 (19.9) | 19,726 (27.6) | |

| 1996–1998 | 15,620 (21.2) | 403 (20.2) | 15,217 (21.3) | |

| 1999–2001 | 12,986 (17.7) | 401 (20.1) | 12,585 (17.6) | |

| 2002–2004 | 12,969 (17.6) | 382 (19.2) | 12,587 (17.6) | |

| 2005–2007 | 11,892 (16.2) | 408 (20.5) | 11,484 (16.0) | <.0001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 21,646 (29.4) | 593 (29.8) | 21,053 (29.4) | |

| Male | 51,944 (70.6) | 1,398 (70.2) | 50,546 (70.6) | .71 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 37,842 (51.4) | 1,133 (56.9) | 36,709 (51.3) | |

| Hispanic | 12,922 (17.6) | 211 (10.6) | 12,711 (17.8) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 21,367 (29.0) | 602 (30.2) | 20,765 (29.0) | |

| Other | 1,459 (2.0) | 45 (2.2) | 1,414 (2.0) | <.0001 |

| Age group at diagnosis | ||||

| < 20 years | 1424 (1.9) | 32 (1.6) | 1,392 (1.9) | |

| 20–39 years | 36,941 (50.2) | 999 (50.2) | 35,942 (50.2) | |

| 40–59 years | 31,347 (42.6) | 820 (41.2) | 30,527 (42.6) | |

| 60 years or older | 3,878 (5.3) | 140 (7.0) | 3,738 (5.2) | .003 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||

| Median (range) | 39 (0–99) | 39 (0–96) | 39 (0–99) | |

| Inter-quartile range | 13 | 15 | 13 | .77 |

| Place of birth | ||||

| United States | 56,970 (77.4) | 1,816 (91.2) | 55,154 (77.0) | |

| Not United States | 16,620 (22.6) | 175 (8.8) | 16,445 (23.0) | <.0001 |

| Mode of transmission | ||||

| Men who have sex with men | 26,862 (36.5) | 504 (25.3) | 26,358 (36.8) | |

| Injection drug useb | 12,645 (17.2) | 415 (20.8) | 12,230 (17.1) | |

| Heterosexual | 23,943 (32.5) | 762 (38.3) | 23,181 (32.4) | |

| Other/unknown | 10,140 (13.8) | 310 (15.6) | 9,830 (13.7) | <.0001 |

| Lowest CD4 count/µl or CD4% categoryc | ||||

| < 20 or < 3% | 14,028 (19.2) | 386 (19.5) | 13,642 (19.2) | |

| 20–53 or 3%–5% | 12,818 (17.5) | 361 (18.2) | 12,457 (17.5) | |

| 54–110 or 6%–8% | 12,405 (16.9) | 349 (17.6) | 12,056 (16.9) | |

| 111–161 or 9%–11% | 12,344 (16.9) | 328 (16.6) | 12,016 (16.9) | |

| 162–199 or 12%–13% | 10,526 (14.4) | 278 (14.0) | 10,248 (14.4) | |

| Met case definition with opportunistic infection only or unknown CD4 count/CD4% | 11,095 (15.2) | 280 (14.1) | 10,815 (15.2) | .71 |

| ZIP code tabulation area (ZCTA) level characteristics | ||||

| Index of poverty in ZCTAc, d | ||||

| Less poverty (< −0.138) | 21,921 (29.8) | 115 (5.8) | 21,806 (30.5) | |

| More poverty (≥ −0.138) | 51,661 (70.2) | 1,876 (94.2) | 49,785 (69.5) | <.0001 |

| Townsend-like index of deprivation for ZCTAd | ||||

| Less deprivation (< −0.159) | 11,985 (16.3) | 470 (23.6) | 11,515 (16.1) | |

| More deprivation (≥ −0.159) | 61,605 (83.7) | 1,521 (76.4) | 60,084 (83.9) | <.0001 |

| Lack of affluence index for ZCTAc, d | ||||

| More affluence (< 0.262) | 32,728 (44.5) | 193 (9.7) | 32,535 (45.5) | |

| Less affluence (≥ 0.262) | 40,775 (55.5) | 1,794 (90.3) | 38,981 (54.5) | <.0001 |

| County level characteristics | ||||

| Average total number of MD/DO per 100 square miles | ||||

| < 19.744 | 2,054 (2.8) | 1,633 (82.0) | 421 (0.6) | |

| ≥ 19.744 | 71,536 (97.2) | 358 (18.0) | 71,178 (99.4) | <.0001 |

| Average number of hospitals per 100 square miles | ||||

| < 0.2062 | 3,935 (5.4) | 1,202 (60.4) | 2,733 (3.8) | |

| ≥ 0.2062 | 69,655 (94.7) | 789 (39.6) | 68,866 (96.2) | <.0001 |

| Ten year average of age-adjusted homicide rates per 100,000 from 1996–2005 | ||||

| < 5.6 | 21,888 (29.7) | 658 (33.1) | 21,230 (29.7) | |

| ≥ 5.6 | 51,702 (70.3) | 1,333 (67.0) | 50,369 (70.4) | .001 |

| Percent of population always or usually receiving needed social and emotional support | ||||

| < 77.6% | 36,444 (49.5) | 1429 (71.8) | 35,015 (48.9) | |

| ≥ 77.6% | 37,146 (50.5) | 562 (28.2) | 36,584 (51.1) | <.0001 |

| Survival | ||||

| Length of survival in months | ||||

| Median (range) | 45 (0–179) | 42 (0–179) | 45 (0–179) | |

| Inter-quartile range | 82 | 74 | 83 | .03 |

| Three-year survival among those diagnosed before 2005 | ||||

| Alive | 41,904 (67.9) | 1,094 (69.1) | 40,810 (67.9) | |

| Dead | 19,794 (32.1) | 489 (30.9) | 19,305 (32.1) | .30 |

| Five-year survival among those diagnosed before 2003 | ||||

| Alive | 30,913 (58.7) | 753 (57.2) | 30,160 (58.7) | |

| Dead | 21,787 (41.3) | 563 (42.8) | 21,224 (41.3) | .28 |

| Ten-year survival among those diagnosed before 1998 | ||||

| Alive | 12,317 (39.6) | 244 (36.1) | 12,073 (39.7) | |

| Dead | 18,776 (60.4) | 432 (63.9) | 18,344 (60.3) | .06 |

P values from chi-square tests except for CD4 count and CD4 percent which were calculated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Includes men who have sex with men who also reported injection drug use.

For CD4 count/percent category there were 374 missing values (0.5% of total); for poverty index there were 8 missing values (0.01% of total), and for affluence index there were 87 missing values (0.12% of total).

The poverty index includes 4 socioeconomic variables: 1) percent of households in ZIP code tabulation area (ZCTA) below poverty line, 2) percent of households in ZCTA with annual income <$15,000, 3) percent of people ≥25 years old in ZCTA with less than 12th grade education, and 4) income disparity in ZCTA (defined as the ratio of % of low income to % of high income).

The Townsend-like index includes 4 socioeconomic variables: 1) percent of households in ZCTA with no access to a car, 2) percent of households in ZCTA with >1 person per room, 3) percent of households in ZCTA living in rented house, and 4) percent of individuals ≥16 years old in ZCTA who were unemployed.

The affluence index includes 5 socioeconomic variables: 1) median income household in 1999, 2) percent of households in ZCTA with annual income ≥ $150,000, 3) percent of persons in ZCTA aged ≥25 years and older with a graduate or professional degree, 4) percent of persons 16 and older in ZCTA employed in the predominantly high class occupations, and 5) percent of owner-occupied homes in ZCTA worth ≥ $300,000.

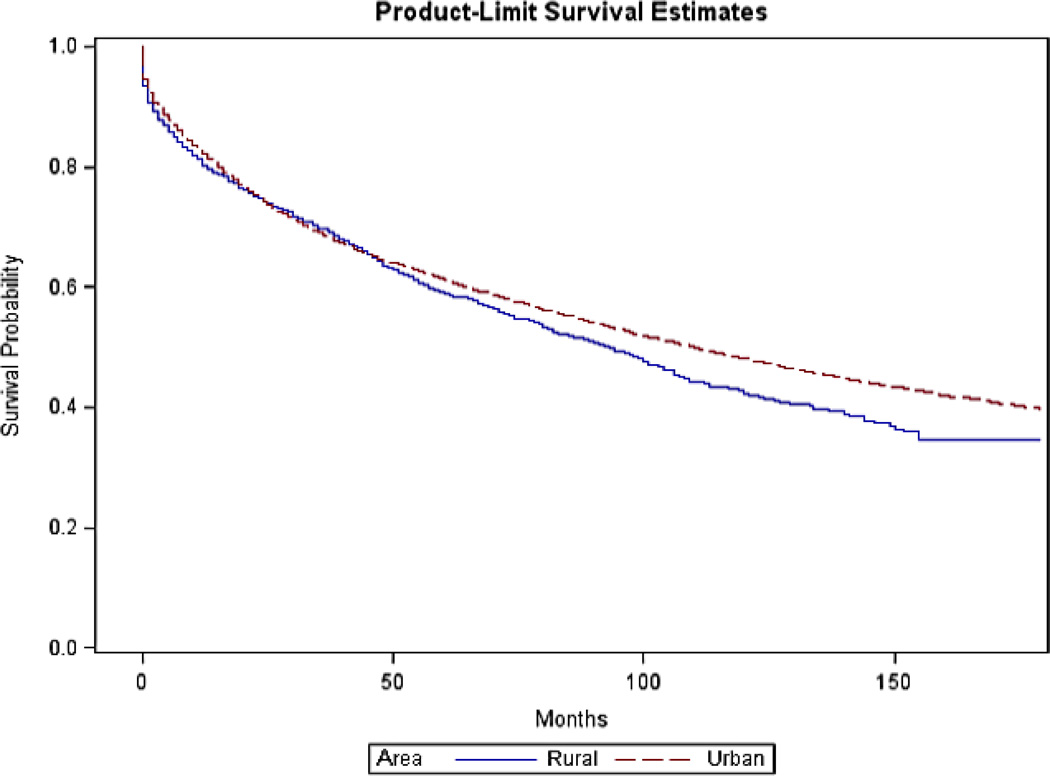

There was no difference in 3- or 5-year survival rates between rural and urban areas (Table 2). However the 10-year survival rate (which only included people diagnosed 1993–1997) was slightly higher in urban (39.7%) compared with rural (36.1%) areas, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .06). In logistic regression modeling for 3-year, 5-year and 10-year survival, there was no statistically significant odds ratio for rural vs urban residence after adjusting for diagnosis cohort, age group, sex, race/ethnicity, US born, transmission mode, and CD4 count/percent category (P values for adjusted OR: 3-year survival .37, 5-year survival .32, 10-year survival .46) (data not in table). The survival curves also indicated no significant difference in short-term survival rates but suggested a survival disadvantage in rural areas in the long term (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier Survival Curves for Rural and Urban Residents in Florida Diagnosed With Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, 1993–2007

In the Cox proportional hazards models, in the rural areas, the following individual variables were associated with an elevated adjusted hazards ratio (aHR) in the final model (Table 3, Model 3): older age at diagnosis, earlier time period of diagnosis, other/unknown transmission mode, and lower CD4 counts/percents. No community-level variables were associated with lower survival.

TABLE 3.

Univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards ratios for Floridians diagnosed with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in rural areas, 1993–2007: hazards ratio* and 95% confidence interval

| Characteristic | Model 1 Unadjusted hazards ratioa (95% CI) n = 1,991† |

Model 2 Adjusted hazards ratioa (95% CI) n = 1,978 |

Model 3 Adjusted hazards ratioa (95% CI) n = 1,982 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-level characteristics | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.14 (0.99–1.32) | 1.12 (0.90–1.40) | |

| Hispanic | 0.94 (0.73–1.21) | 0.92 (0.67–1.26) | |

| Other | 1.17 (0.75–1.83) | 1.13 (0.80–1.61) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | Referent | Referent | |

| Age at diagnosis (per year) | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | 1.03 (1.03–1.04) | 1.03 (1.03–1.04) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 0.88 (0.76–1.02) | 1.07 (0.89–1.28) | |

| Male | Referent | Referent | |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 1993–1995 | 1.86 (1.43–2.42) | 1.95 (1.50–2.53) | 1.93 (1.50–2.48) |

| 1996–1998 | 1.08 (0.82–1.41) | 0.99 (0.74–1.33) | 0.99 (0.74–1.31) |

| 1999–2001 | 0.92 (0.70–1.22) | 0.84 (0.62–1.13) | 0.84 (0.63–1.13) |

| 2002–2004 | 0.90 (0.67–1.20) | 0.82 (0.60–1.12) | 0.82 (0.60–1.12) |

| 2005–2007 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Country of birth | |||

| United States | 1.04 (0.80–1.35) | 0.95 (0.72–1.25) | |

| Not United States | Referent | Referent | |

| Mode of transmission | |||

| Men who have sex with men | 1.08 (0.91–1.28) | 1.13 (0.91–1.40) | 1.07 (0.89–1.28) |

| Injection drug useb | 1.05 (0.87–1.25) | 1.14 (0.90–1.45) | 1.09 (0.87–1.36) |

| Heterosexual | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Other/unknown | 1.83 (1.52–2.22) | 1.74 (1.43–2.10) | 1.70 (1.42–2.05) |

| Lowest CD4 count/µL CD4% categoryc | |||

| < 20 or < 3% | 3.68 (2.79–4.85) | 3.89 (3.01–5.04) | 3.92 (3.02–5.09) |

| 20–53 or 3%–5% | 2.71 (2.05–3.59) | 2.73 (2.09–3.55) | 2.66 (2.03–3.47) |

| 54–110 or 6%–8% | 2.10 (1.58–2.80) | 2.17 (1.60–2.94) | 2.14 (1.60–2.87) |

| 111–161 or 9%–11% | 1.68 (1.24–2.26) | 1.67 (1.28–2.17) | 1.66 (1.29–2.15) |

| 162–199 or 12%–13% | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Met case definition with opportunistic infection only | 3.17 (2.36–4.27) | 2.84 (2.09–3.86) | 2.82 (2.10–3.80) |

| ZCTA-level characteristics | |||

| Poverty: Index of poverty in ZIP code tabulation aread | |||

| Less poverty (< −0.138) | Referent | Referent | |

| More poverty (≥ −0.138) | 1.17 (0.86–1.60) | 1.18 (0.76–1.82) | |

| Townsend: Townsend-like index of deprivation in ZIP code tabulation aread | |||

| Less deprivation (< −0.159) | Referent | Referent | |

| More deprivation (≥ −0.159) | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) | 0.95 (0.72–1.26) | |

| Affluence: Index of lack of affluence in ZIP code tabulation areac,d | |||

| More affluence (< 0.262) | Referent | Referent | |

| Less affluence (≥0.262) | 1.06 (0.80–1.40) | 0.95 (0.66–1.37) | |

| County-level characteristics | |||

| Average total number of MD/DO per 100 square miles | |||

| < 19.744 | 0.96 (0.77–1.19) | 0.91 (0.65–1.28) | |

| ≥ 19.744 | Referent | Referent | |

| Average number of hospitals per 100 square miles | |||

| < 0.2062 | 1.07 (0.86–1.34) | 1.02 (0.76–1.36) | |

| ≥ 0.2062 | Referent | Referent | |

| Ten-year average of age-adjusted homicide rates per 100,000 from 1996–2005 | |||

| < 5.6 | Referent | Referent | |

| ≥ 5.6 | 1.06 (0.85–1.31) | 1.03 (0.78–1.36) | |

| Percent of population always or usually receiving needed social and emotional support | |||

| < 77.6% | 0.95 (0.81–1.12) | 0.89 (0.75–1.07) | |

| ≥ 77.6% | Referent | Referent |

Model 1: Only single factors were considered one at a time in the model. Hazards ratios are not adjusted for any other factors. Model 2: Hazards ratios are adjusted for all characteristics in the table. Model 3: Hazards ratios are adjusted for only the statistically significant characteristics in the table. Manual backward selection was performed (based on P value ≥ .05).

Includes men who have sex with men who also reported injection drug use.

For CD4 count/percent category there were 9 missing values (0.5% of total), and for affluence index there were 4 missing values (0.2% of total).

Poverty index includes 4 socioeconomic status (SES) variables, namely, percentage of households in ZIP code tabulation area (ZCTA) below poverty line, percentage of households in ZCTA with annual income less than $15,000, percentage of individuals in ZCTA with less than 12th grade education, and income disparity in ZCTA (defined as the ratio of % of low income to % of high income).

Townsend-like index includes 4 SES variables, namely, percentage of households in ZCTA with no access to a car, percentage of households in ZCTA with more 1 person per room, percentage of households in ZCTA living in rented house, and percentage of individuals 16 years old or more in ZCTA unemployed.

Affluence index includes 5 SES variables, namely, median income household in 1999, percentage of households in ZCTA with annual income of at least $150,000, percentage of persons in ZCTA aged 25 years and older with a graduate or professional degree, percentage of persons in ZCTA employed in the predominantly high working class occupations, percentage of owner-occupied homes in ZCTA worth at least $300,000.

In urban areas, belonging to the non-Hispanic black, Hispanic or other racial/ethnic group; older age at the time of diagnosis; earlier time period of diagnosis; US country of birth; IDU and other/unknown modes of transmission; and low CD4 count/percent categories were associated with a higher aHR (Table 4). The community-level variables poverty index, lower physician density, and lower social support were also associated with a higher aHR.

TABLE 4.

Univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) among people diagnosed with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in urban areas, 1993–2007: hazards ratio and 95% confidence interval

| Characteristic | Model 1 Unadjusted hazards ratio (95% CI)a n = 71,599 |

Model 2 Adjusted hazards ratioa (95% CI) n = 71,143 |

Model 3 Adjusted hazards ratioa (95% CI) n = 71,226 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-level characteristics | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.27 (1.24–1.30) | 1.19 (1.13–1.25) | 1.19 (1.14–1.25) |

| Hispanic | 0.97 (0.93–1.00) | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) | 1.07 (1.01–1.12) |

| Other | 1.25 (1.16–1.35) | 1.26 (1.15–1.37) | 1.26 (1.15–1.38) |

| Non-Hispanic white | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Age at diagnosis (per year) | 1.02 (1.02–1.02) | 1.03 (1.03–1.03) | 1.03 (1.03–1.03) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | |

| Male | Referent | Referent | |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 1993–1995 | 2.33 (2.22–2.46) | 2.43 (2.30–2.56) | 2.43 (2.30–2.57) |

| 1996–1998 | 1.34 (1.27–1.42) | 1.32 (1.26–1.39) | 1.33 (1.26–1.40) |

| 1999–2001 | 1.15 (1.08–1.21) | 1.09 (1.03–1.16) | 1.09 (1.04–1.16) |

| 2002–2004 | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) |

| 2005–2007 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Country of birth | |||

| United States | 1.21 (1.17–1.24) | 1.34 (1.29–1.40) | 1.35 (1.29–1.41) |

| Not United States | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Mode of transmission | |||

| Men who have sex with men | 0.94 (0.91–0.96) | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) |

| Injection drug useb | 1.30 (1.26–1.34) | 1.19 (1.14–1.24) | 1.17 (1.12–1.23) |

| Heterosexual | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Other/unknown | 1.83 (1.77–1.90) | 1.74 (1.67–1.82) | 1.73 (1.66–1.80) |

| Lowest CD4 count/µL CD4% categoryc | |||

| < 20 or < 3% | 2.60 (2.49–2.72) | 2.58 (2.47–2.71) | 2.58 (2.46–2.70) |

| 20–53 or 3%–5% | 2.09 (2.00–2.18) | 2.09 (1.99–2.19) | 2.08 (1.99–2.18) |

| 54–110 or 6%–8% | 1.70 (1.63–1.78) | 1.66 (1.59–1.74) | 1.66 (1.59–1.74) |

| 111–161 or 9%–11% | 1.26 (1.21–1.32) | 1.24 (1.18–1.31) | 1.24 (1.18–1.31) |

| 162–199 or 12%–13% | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Met case definition with opportunistic infection only | 2.27 (2.16–2.37) | 1.96 (1.85–2.08) | 1.96 (1.85–2.08) |

| ZCTA-level characteristics | |||

| Poverty: Index of poverty in ZIP code tabulation areac, d | |||

| Less poverty (< −0.138) | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| More poverty (≥ −0.138) | 1.20 (1.09–1.31) | 1.10 (1.06–1.16) | 1.11 (1.06–1.17) |

| Townsend: Townsend-like index of deprivation in ZIP code tabulation area (ZCTA)d | |||

| Less deprivation (< −0.159) | Referent | Referent | |

| More deprivation (≥ −0.159) | 1.09 (0.96–1.24) | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | |

| Affluence: Index of lack of affluence in ZCTAc,d | |||

| More affluence (< 0.262) | Referent | Referent | |

| Less affluence (≥0.262) | 1.12 (1.05–1.21) | 1.03 (0.98–1.07) | |

| County-level characteristics | |||

| Average total number of MD/OD per 100 square miles | |||

| < 19.744 | 1.06 (0.91–1.25) | 1.22 (1.05–1.42) | 1.17 (1.02–1.33) |

| ≥ 19.744 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Average number of hospitals per 100 square miles | |||

| < 0.2062 | 0.87 (0.77–0.98) | 0.94 (0.87–1.01) | |

| ≥ 0.2062 | Referent | Referent | |

| Ten year average of age-adjusted homicide rates per 100,000 from 1996–2005 | |||

| < 5.6 | Referent | Referent | |

| ≥ 5.6 | 1.07 (1.00–1.13) | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) | |

| Percent of population always or usually receiving needed social and emotional support | |||

| < 77.6% | 1.05 (0.99–1.12) | 1.04 (0.99–1.08) | 1.05 (1.01–1.10) |

| ≥ 77.6% | Referent | Referent | Referent |

Model 1: Only single factors were considered one at a time in the model. Hazards ratios are not adjusted for any other factors. Model 2: Hazards ratios are adjusted for all characteristics in the table. Model 3: Hazards ratios are adjusted for only the statistically significant characteristics in the table. Manual backward selection was performed (based on p-value ≥ 0.05).

Includes men who have sex with men who also reported injection drug use.

For CD4 count/percent category there were 365 missing values (0.50% of total), for affluence index there were 83 missing values (0.12% of total), and for poverty index there were 8 missing values (0.01% of total).

Poverty index includes 4 socioeconomic status (SES) variables, namely, percentage of households in ZCTA below poverty line, percentage of households in ZCTA with annual income less than $15,000, percentage of individuals in ZCTA with less than 12th grade, and income disparity in ZCTA (defined as the ratio of % of low income to % of high income).

Townsend-like index includes 4 SES variables, namely, percentage of households in ZCTA with no access to a car, percentage of households in ZCTA with more 1 person per room, percentage of households in ZCTA living in rented house, and percentage of individuals 16 years old or more in ZCTA unemployed.

Affluence index includes 5 SES variables, namely, median income household in 1999, percentage of households in ZCTA with annual income of at least $150,000, percentage of persons in ZCTA aged 25 years and older with a graduate or professional degree, percentage of persons in ZCTA employed in the predominantly high working class occupations, and percentage of owner-occupied homes in ZCTA area worth at least $300,000.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that a small percentage (2.7%) of people reported with AIDS in Florida during 1993–2007 resided in a rural area at the time of diagnosis. Of note, however, the percentage of diagnoses that were from rural areas has increased over time, principally due to the number of urban diagnoses declining. This suggests that the prevention of HIV and/or the prevention of clinical progression to AIDS has been more effective in urban areas.

In rural areas, the more recent cohorts were older, more likely to be female, be a racial/ethnic minority, and have a reported transmission mode of heterosexual sex. The increase in representation of females and those reporting a transmission mode of heterosexual sex was seen nationally (in rural and urban areas combined) during the same time period.50 It should be noted, however, that the most recent rural Florida cohort (2005–2007) had a slightly lower percentage of non-Hispanic blacks (58.3%) than in rural areas of the southern region of the US in 2006 (61.9%).2 Also, during 2005–2007, there was a somewhat higher proportion of Hispanics among people diagnosed with AIDS in rural Florida (10.8%) than in the southern rural region of the US in 2006 (6.8%). Compared to people diagnosed with AIDS in urban areas, those diagnosed in rural areas were less likely to be Hispanic, born outside the US, and have a reported mode of transmission of MSM, likely reflecting the underlying demographic differences between urban and rural areas in Florida.

In the current study the declining proportion of people being diagnosed at very low CD4 counts/CD4 percent values with each subsequent cohort suggests that over time people were being diagnosed with AIDS at an earlier clinical stage. There was no indication that rural residents were being diagnosed later than urban residents based on the CD4 counts/CD4 percent category at time of diagnosis. This is contrary to what was found in a population-based study of rural residents in South Carolina during a similar period (2001–2005).20 In that study, rural residents diagnosed with HIV infection had a significantly lower CD4 count than those in urban areas. However, that difference was no longer significant after controlling for sex, race, age, and mode of transmission. Survival, however, was not evaluated in the South Carolina study. The study also differed from the current one in its inclusion of people whose HIV infection had not progressed to AIDS, and in the demographic characteristics of the rural population (eg, a higher percentage of women, a higher percentage of non-Hispanic blacks and a lower percentage of Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites). A national study of people receiving HIV care in the Veterans Administration health care system during 1998–2006 found that compared with urban residents, rural residents had a lower CD4 count at entry into care and were more likely to have an AIDS-defining illness within 180 days of care initiation.17 That study also differed from the current one because cases which had not yet progressed to AIDS were included, and it included only Veterans Administration patients.

The results of the current study indicate that, compared with urban residents, rural residents were not disadvantaged with respect to survival with AIDS in the short term (3 years) or medium term (5 years). The survival curves and 10-year survival rates suggested that there might be a survival disadvantage for rural residents in the long term. This finding, however, should be interpreted cautiously because the records available for analysis of 10-year survival were by necessity diagnoses from 1993 to 1997. Much of that time period was prior to the time when HAART became available.51

We found no other published population-based studies comparing survival from time of AIDS diagnosis to death between rural and urban residents in the US. The results of several clinic-based studies have been inconsistent. A national study of people receiving HIV care in the Veterans Administration during 1998–2006 found an elevated crude hazards ratio for mortality for rural residents that was no longer significant after adjusting for baseline CD4 count and presence of AIDS-defining illness at baseline.17 Another study of 644 patients with HIV infection cared for between 1995 and 2005 in a multisite clinic in New England found decreased survival using logistic regression among rural residents, even after controlling for age, sex, race, mode of transmission, year of diagnosis, travel time, insurance, and receipt of antiretroviral medications or prophylaxis for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia.18 A third, smaller study in Vermont found no survival difference between 223 urban and 140 rural patients with HIV infection receiving care during 1996–2006; however, all these patients were receiving care from affiliated HIV specialty clinics.19

Compared to urban areas, there were relatively few factors associated with survival for rural areas. Of note, there were no significant racial/ethnic differences in survival in the rural areas, although there were in the urban areas, where non-Hispanic blacks and to a lesser extent Hispanics were disadvantaged relative to non-Hispanic whites. One possible explanation is that income inequalities among racial/ethnic groups may be smaller in rural areas than in urban areas, but these data were not available for analysis. Older age at the time of diagnosis, on the other hand, was associated with lower survival in both areas, as has been reported in other studies.29,32,52,53 Not surprisingly, in both areas, diagnosis during earlier time periods was associated with lower survival, which is to be expected given the significant advances in HIV/AIDS treatment.51 Having an unknown transmission category was also associated with lower survival in both areas. This may be due to information not being collected because the person died rapidly or because people who deny risk may deny signs and symptoms and delay seeking medical care and subsequently diagnosis.

The socioeconomic status of the area where the person was diagnosed was not associated with survival in rural areas. In urban areas, there was a clear association between decreased survival and low socioeconomic status, whether measured by the poverty index or the low affluence index. The association between decreased survival and individual- and area-level low socioeconomic status has been reported by others.29,54–61 The lack of an association found in Florida’s rural areas may be due to rural ZCTAs having a more heterogeneous distribution of people with regard to socioeconomic status than urban ZCTAs.62 Therefore, it is likely that the rural area socioeconomic measures are less reflective of individual SES than urban measures. Additionally, there may be some unmeasured cultural factors present only in rural areas in Florida that may lessen the impact of low socioeconomic status on AIDS disease progression. It would be beneficial for future studies to measure socioeconomic status in smaller geographic areas or at the individual level to further investigate the role of socioeconomic status in AIDS survival in rural areas.

There are several limitations in this study. First, we assume that the place of diagnosis is where patients continue to live after their diagnosis. However, a study using the HIV Cost and Services Utilization data found that 32% of people move to another city or state at least once after HIV diagnosis,63 and a study in Florida found that 25% of people receiving HIV treatment had migrated to a non-contiguous county, or another state or country.64 Second, although we were able to convert the ZIP codes to ZCTAs for all but 34 (0.04%) records, it is possible that the ZCTAs did not always encompass the same geographic areas as ZIP codes.65 Third, we were limited in our analysis to using AIDS surveillance data. Thus, our results may not apply to people with HIV infection whose illness has not progressed to AIDS. However, this limitation applies more to the analysis of the AIDS diagnosis data than to the survival analysis, since deaths among those whose HIV infection had not progressed to AIDS would be a somewhat uncommon occurrence. Fourth, there were limited baseline clinical data. For example, there was no information about viral load, co-morbidities, or receipt of antiretroviral therapy. Finally, Florida’s rural areas are not as distant from major metropolitan areas as some “frontier” rural areas in the western part of the United States. In addition, the rural categorization is based on population size and commuting patterns independent of the underlying industries or cultures. Therefore, it is likely that access to HIV/AIDS-related care and subsequent survival may be somewhat different in rural Florida than it is in rural areas of other states.

In conclusion, rural AIDS diagnoses in Florida are a small proportion of all AIDS diagnoses, although the proportion has been increasing over time. The epidemiology of AIDS in rural Florida has been changing over time with increasing proportions of older, female and non-Hispanic black people. Modifications in the delivery of AIDS-related services in rural areas may be needed to respond to these changing demographics. People diagnosed with AIDS in rural Florida during 1993–2007 do not seem to be appreciably disadvantaged with regard to either later diagnosis or AIDS survival time compared with people living in urban areas. However, different factors among residents diagnosed with AIDS were associated with survival, depending on whether residents lived in rural vs urban areas. This suggests that rural populations living with AIDS should be assessed separately from urban populations. There is also the need for more population-based studies in rural areas that gather individual-level socioeconomic and clinical information to better assess the needs of rural residents living with HIV/AIDS as well as population-based studies that assess clinical outcomes including survival from the time of HIV as opposed to AIDS diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number R01MD004002 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities at the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities or the National Institutes of Health. The authors wish to thank Tracina Bush, BS; Julia Fitz, MPH; Khaleeq Lutfi, MPH; and Elena McCalla-Pavlova, MD, MHSA, for assistance in preparing the dataset.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Supplemental Report. Vol. 22. Atlanta, GA: 2010. [Accessed July 19, 2012]. March 2012. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2010report/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Supplemental Report. No. 2. Vol. 13. Atlanta, GA: 2008. [Accessed December 11, 2011]. June 1, 2010. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2008supp_vol13no2/pdf/HIVAIDS_SSR_Vol13_No2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham RP, Forrester ML, Wysong JA, Rosenthal TC, James PA. HIV/AIDS in the rural United States: epidemiology and health services delivery. Med Care Res Rev. 1995;52(4):435–452. doi: 10.1177/107755879505200401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schur CL, Berk ML, Dunbar JR, Shapiro ME, Cohn SE, Bozzette SA. Where to seek care: an examination of people in rural areas with HIV/AIDS. J Rural Health. 2002;18(2):337–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2002.tb00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutton M, Anthony M, Vila C, McLellan-Lemal E, Weidel PJ. HIV testing and HIV/AIDS treatment services in rural counties in 10 southern states: service provider perspectives. J Rural Health. 2010;26:240–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kempf M, McLeod J, Boehme AK, et al. A qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators to retention–in-care among HIV-positive women in the rural southeastern United States: implications for targeted interventions. AIDS Patient Care ST. 2010;24(8):515–520. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitahata MM, Koepsell TD, Deyo RA, Maxwell CL, Dodge WT, Wagner EH. Physicians’ experience with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome as a factor in patients’ survival. New Engl J Med. 1996;334:701–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett CL, Garfinkle JB, Greenfield S, et al. The relation between hospital experience and in-hospital mortality for patients with AIDS related PCP. JAMA. 1989;261(20):2975–2979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham WE, Tisnado DM, Lui HH, Nakazono TT, Carlisle DM. The effect of hospital experience on mortality among patients hospitalized with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in California. Am J Med. 1999;107:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohn SE, Berk ML, Berry SH, et al. The care of HIV-infected adults in rural areas of the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28(4):385–392. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200112010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen TQ, Whetten K. Is anybody out there? Integrating HIV services in rural regions. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:3–9. doi: 10.1093/phr/118.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whetten K, Reif S. Overview: HIV/AIDS in the deep south region of the United States. AIDS Care. 2006;18(Suppl 1):S1–S5. doi: 10.1080/09540120600838480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reif S, Whetten K, Lowe K, Ostermann J. Association of unmet needs for support services with medication use and adherence among HIV-infected individuals in the southeastern United States. AIDS Care. 2006;18(4):277–283. doi: 10.1080/09540120500161868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heckman TG, Somlai AM, Peters J, et al. Barriers to care among persons living with HIV/AIDS in urban and rural areas. AIDS Care. 1998;10(3):365–375. doi: 10.1080/713612410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whetten-Goldstein K, Nguyen TQ, Heald AE. Characteristics of individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus and provider interaction in the predominantly rural southeast. South Med J. 2001;94(2):212–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mainous AG, Matheny SC. Rural human immunodeficiency virus health service provision. Indications of rural-urban travel for care. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5(8):469–473. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.8.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohl M, Tate J, Duggal M, et al. Rural residence is associated with delayed care entry and increased mortality among veterans with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Med Care. 2010;48(12):1064–1070. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ef60c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lahey T, Lin M, Marsh B, et al. Increased mortality in rural patients with HIV in New England. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23(5):693–698. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grace C, Kutzko D, Alston WK, Ramundo M, Polish L, Osler T. The Vermont model for rural HIV care delivery: eleven years of outcome data comparing urban and rural clinics. J Rural Health. 2010;26(2):113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weis KE, Liese AD, Hussey J, Gibson JJ, Duffus WA. Associations of rural residence with timing of HIV diagnosis and stage of disease at diagnosis, South Carolina 2001–2005. J Rural Health. 2010;26(2):105–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. [Accessed December 11, 2011];MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1992 41(RR-17):1–19. December 18, 1992. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00018871.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trepka MJ, Maddox LM, Lieb S, Niyonsenga T. Utility of the National Death Index in ascertaining mortality in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome surveillance. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(1):90–98. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hessol NA, Buchbinder SP, Colbert D, et al. Impact of HIV infection on mortality and accuracy of AIDS reporting on death certificates. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(4):561–564. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.4.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnold M, Hsu L, Pipkin S, McFarland W, Rutherford GW. Race, place and AIDS: the role of socioeconomic context on racial disparities in treatment and survival in San Francisco. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(1):121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blair JM, Fleming PL, Karon JM. Trend in AIDS incidence and survival among racial/ethnic minority men who have sex with men, United States, 1990–1999. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(3):339–347. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200211010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Detels R, Muňoz A, McFarlane G, et al. Effectiveness of potent antiretroviral therapy on time to AIDS and death in men with known HIV infection duration. JAMA. 1998;280(17):1497–1503. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.17.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grigoryan A, Hall HI, Durant T, Wei X. Late HIV diagnosis and determinants of progression to AIDS or death after HIV diagnosis among injection drug users, 33 US states, 1996–2004. PLoS One. 2009;4(2):e4445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall HI, Byers RH, Ling Q, Espinoza L. Racial/ethnic and age disparities in HIV prevalence and disease progression among men who have sex with men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):1060–1066. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDavid Harrison K, Ling Q, Song R, Hall HI. County-level socioeconomic status and survival after HIV diagnosis, United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(12):919–927. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McFarland W, Chen S, Hsu L, et al. Low socioeconomic status is associated with a higher rate of death in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy, San Francisco. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(1):96–103. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200305010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider ML, Gange SJ, Wiliams CM, et al. Patterns of the hazard of death after AIDS through the evolution of antiretroviral therapy: 1984–2004. AIDS. 2005;19(17):2009–2018. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000189864.90053.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwarcz SK, Hsu LC, Vittinghoff E, Katz MH. Impact of protease inhibitors and other antiretroviral treatments on acquired immunodeficiency syndrome survival in San Francisco, California, 1987–1996. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(2):178–185. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silverberg MJ, Wegner SA, Milazzo MJ, et al. Effectiveness of highly-active antiretroviral therapy by race/ethnicity. AIDS. 2006;20(11):1531–1538. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000237369.41617.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Quesenberry CP, et al. Race/ethnicity and risk of AIDS and death among HIV-infected patients with access to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):1065–1072. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1049-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Census Bureau. Census 2000 ZCTAs™, ZIP Code Tabulation Areas Technical Documentation. [Accessed October 22, 2011]; Available at http://www.census.gov/geo/ZCTA/zcta_tech_doc.pdf.

- 36.Diez-Roux AV, Kiefe CI, Jacobs DR, Jr, et al. Area characteristics and individual-level socioeconomic position indicators in three population-based epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11(6):395–405. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV, Carson R. Geocoding and monitoring of US socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: does the choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter? The Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project (US) Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(5):471–482. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Messer LC, Laraia BA, Kaufman JS, et al. The development of a standardized neighborhood deprivation index. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1041–1062. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9094-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh GK, Siahpush M. Increasing inequalities in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among US adults aged 25–64 years by area socioeconomic status, 1969–1998. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(3):600–613. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.3.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zierler S, Krieger N, Tang Y, et al. Economic deprivation and AIDS incidence in Massachusetts. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(7):1064–1073. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niyonsenga T, Trepka MJ, Lieb S, Maddox LM. Measuring socioeconomic inequality in the incidence of AIDS: rural-ruban considerations. AIDS Behavior. 2012 Jun 19; doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0236-8. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Townsend P. Deprivation. J Soc Policy. 1987;16:125–146. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Area Resource File (ARF) Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Florida Department of Health Office of Health Statistics and Assessment. Florida Community Health Assessment Resource Toolset (CHARTS) [Accessed July 18, 2011]; Available at http://www.floridacharts.com/charts/chart.aspx.

- 45.Hart LG, Larsen EH, Lishner DM. Rural Definitions for Health Policy and Research. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1149–1155. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.WWAMI Rural Health Research Center. Rural Urban Commuting Areas (RUCA) [Accessed December 12, 2012]; No date. Available at http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-uses.php.

- 47.US. Bureau of Census. American Factfinder. Census 2000 Summary File 1. [Accessed December 12, 2011]; No date. Available at http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DTGeoSearchByListServlet?ds_name=DEC_2000_SF1_U&state=d.

- 48.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, May S. Applied Survival Analysis: Regression Modeling of Time to Event Data. 2nd Edition. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 49.SAS. Version 9.2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2002–2008. [computer program)]. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS—United States, 1981–2005. [Accessed December 19, 2011];MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006 55(21):589–592. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5521a2.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wynn GH, Zapor MJ, Smith BH, et al. Antiretrovirals, part 1: overview, history and focus on protease inhibitors. Psychosomatics. 2004;45:262–270. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jain S, Schwarcz S, Katz M, Gulati R, McFarland W. Elevated risk of death for African Americans with AIDS, San Francisco, 1996–2002. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(3):493–503. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nash D, Katyal M, Shah S. Trends in predictors of death due to HIV-related causes among persons living with AIDS in New York City: 1993–2001. J Urban Health. 2005;82(4):584–600. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen SY, Moss WJ, Pipkin SS, McFarland W. A novel use of AIDS surveillance data to assess the impact of initial treatment regimen on survival. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20(5):330–335. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cunningham WE, Andersen RM, Katz MH, et al. The impact of competing subsistence needs and barriers on access to medical care for persons with human immunodeficiency virus receiving care in the United States. Med Care. 1999;37(12):1270–1281. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cunningham WE, Hays RD, Duan N, et al. The effect of socioeconomic status on the survival of people receiving care for HIV infection in the United States. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(4):655–676. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hall HI, McDavid K, Ling Q, Sloggett A. Determinants of progression to AIDS or death after HIV diagnosis, United States 1996 to 2001. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(11):824–833. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fordyce EJ, Singh TP, Nash D, Gallagher B, Forlenza S. Survival rates in NYC in the era of combination ART. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(1):111–118. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200205010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Joy R, Druyts EF, Brandson EK, et al. Impact of neighborhood-level socioeconomic status on HIV disease progression in universal health care setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(4):500–505. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181648dfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rapiti E, Porta D, Forastiere F, et al. Socioeconomic status and survival of persons with AIDS before and after the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Epidemiology. 2000;11(5):496–501. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wood E, Montaner JS, Chan K, et al. Socioeconomic status, access to triple therapy, and survival from HIV-disease since 1996. AIDS. 2002;16(15):2065–2072. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200210180-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haynes R, Gale S. Deprivation and poor health in rural areas: inequalities hidden by averages. Health Place. 2000;6(4):275–285. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(00)00009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.London AS, Wilmoth JM, Fleishman JA. Moving for care: findings from the US HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. AIDS Care. 2004;16(7):858–875. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331290149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lieb S, Trepka MJ, Liberti TM, Cohen L, Romero J. HIV/AIDS patients who move to urban Florida counties following a diagnosis of HIV: predictors and implications for HIV prevention. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1158–1167. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9128-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krieger N, Waterman P, Chen JT, Soobad M, Suvramian SV, Carson R. Zip code caveat: bias due to spatiotemporal mismatches between zip codes and US Census-defined geographic areas-the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Pub Health. 2002;92(7):1100–1102. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.7.1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]