Abstract

Tubes of differing cellular architecture connect into networks. In the Drosophila tracheal system, two tube types connect within single cells (terminal cells); however, the genes that mediate this interconnection are unknown. Here we characterize two genes that are essential for this process: lotus, required for maintaining a connection between the tubes, and wheezy, required to prevent local tube dilation. We find that lotus encodes N-ethylmaleimide Sensitive Factor 2 (NSF2), while wheezy encodes Germinal Center Kinase III (GCKIII). GCKIIIs are effectors of Cerebral Cavernous Malformation 3 (CCM3), a protein mutated in vascular disease. Depletion of CCM3 by RNA interference phenocopies wheezy; thus, CCM3 and GCKIII, which prevent capillary dilation in humans, prevent tube dilation in Drosophila trachea. Ectopic junctional and apical proteins are present in wheezy terminal cells, and we show that tube dilation is suppressed by reduction of NSF2, of the apical determinant Crumbs, or of septate junction protein Varicose.

INTRODUCTION

Most organs are composed of epithelial or endothelial cells organized as tubes; junctional complexes maintain the intercellular or auto-cellular connections (“seams”) that seal the cells into selectively permeable tubes. Should these connections be compromised, the consequences for organ function can be catastrophic. For example, individuals with the vascular disease, familial cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM), may suffer from seizures and strokes as a consequence of dilated leaky tubes (Clatterbuck et al., 2001; Haasdijk et al., 2011; Rigamonti et al., 1988).

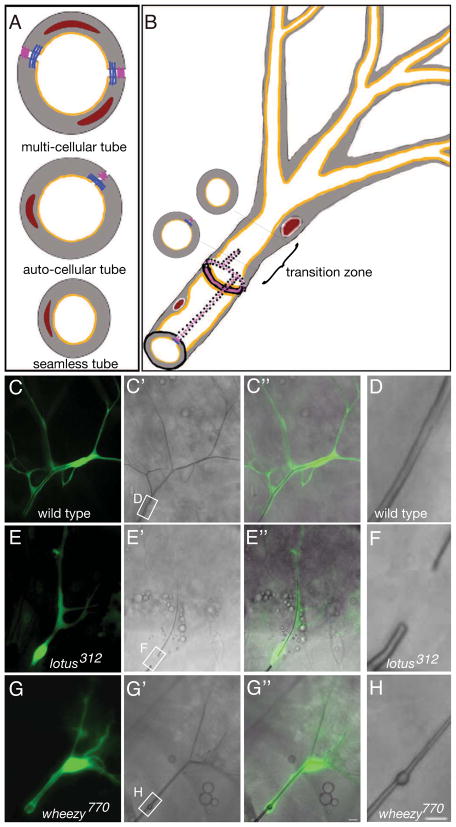

Three architecturally distinct tube types have been described (Lubarsky and Krasnow, 2003), and all three are found in the Drosophila tracheal system. These include multicellular seamed tubes (with intercellular junctions), seamed tubes formed by single cells (with auto-cellular junctions), and seamless tubes formed within single cells (no junctions)(Ribeiro et al., 2004; Samakovlis et al., 1996a) (Figure 1A). Most seamless tubes are thought to form intracellularly, although they may also form by fusion of membrane along auto-cellular junctions, converting auto-cellular tubes into seamless ones (Lubarsky and Krasnow, 2003; Rasmussen et al., 2008; Stone et al., 2009).

Figure 1. Identification of mutants with tube defects in the terminal cell transition zone.

Three distinct tube architectures (A) are found in the tracheal system. Multi-cellular tubes (top panel; 2 –5 cells around the circumference of the tube; adherens junctions, blue; septate junctions, magenta; nuclei, brick red; cytoplasm, grey; apical membrane, mustard) are found along the dorsal trunks of the tracheal system, while single cells make the auto-cellular tubes (middle panel) that comprise most primary tracheal branches, and intracellular seamless tubes (bottom panel) are found in the cells that make secondary and tertiary tracheal branches. Terminal cells (B) mark the ends of the tracheal tubes. They are connected via intercellular junctions to a stalk cell. A line of junctional staining stretches from the intercellular junction into the terminal cell, suggesting that the proximal part of the terminal cell tube is auto-cellular. A transition from auto-cellular to seamless occurs at a variable position between the intercellular junction and the terminal cell nucleus (red) – we refer to this region of the terminal cell as the transition zone. In (C–H) micrographs of positively marked (GFP, green) homozygous tracheal clones in terminal cell positions are shown in third instar larvae. In control clones (C–D), a terminal cell with multiple cellular extensions (C), contains gas-filled tubes (C′); refraction of light reveals the gas-filling state in brightfield microscopy. In a merged image (C″), it is apparent that single gas-filled tubes are present in each cellular extension. The rectangular box in C′ marks the transition zone, shown at higher magnification in (D). (D) a smooth gas-filled tube is detected with no obvious difference in morphology marking the junction of seamed and seamless tubes. In lotus mutant clones (E–F), terminal cells are smaller with fewer branches and exhibit a gas-filling gap within the transition zone. In wheezy mutant clones (G–H), a single large dilation is detected within the tube of the transition zone. Scale bars = 5 microns. See also Figure S1.

Tubes with single seams (auto-cellular) and seamless tubes form relatively late during tracheal development. The first tubes of the tracheal system are large multi-cellular sacs generated by invagination from the embryonic ectoderm. The tracheal epithelial cells are polarized along their apical-basolateral axis, with the apical membrane of each cell facing the lumen of the tracheal sac to which it belongs. Cells are next recruited to the distinct primary branches that migrate away from the sacs towards Branchless-FGF chemo-attractant cues (Sutherland et al., 1996). Many of the primary branches initially form short wide tubes that lengthen and narrow over time, as the cells that comprise them intercalate, changing the underlying tubular architecture from multi-cellular to auto-cellular (Ribeiro et al., 2004). Tip cells are required for, and lead, the migration of the new branches (Ghabrial and Krasnow, 2006). Ultimately, tip cells assume specialized cell fates (terminal cell or fusion cell), and initiate secondary branch formation by targeting apical membrane internally to form seamless tube (Gervais and Casanova, 2010; Gervais et al., 2012; Ikeya and Hayashi, 1999; Lee and Kolodziej, 2002; Llimargas, 1999; Samakovlis et al., 1996a; Samakovlis et al., 1996b). The precise mechanism by which this occurs remains subject to debate and may differ between terminal and fusion cells (Gervais and Casanova, 2010; Lubarsky and Krasnow, 2003; Schottenfeld-Roames and Ghabrial, 2012; Uv et al., 2003).

Intriguingly, Drosophila terminal cells contain both auto-cellular and seamless tubes ((Samakovlis et al., 1996a), but see also (Gervais and Casanova, 2010)). Transition from one tube type (auto-cellular) to the other (seamless) occurs within the terminal cell at a location proximal to the terminal cell nucleus (Figure 1B). This observation raises a number of questions including: how do the two tube types connect to each other, how do they match each other in diameter, and which pathways are required to regulate and execute these processes? To begin to address these questions we have taken a genetic approach, and have screened through a large collection of terminal cell mutants (Ghabrial et al., 2011) to identify those that display tube morphogenesis defects within the region of the terminal cell wherein the auto-cellular-to-seamless tube transition occurs (hereafter, the “transition zone”).

Here we report the identification and characterization of two mutants that disrupt lumen morphology in the transition zone in strikingly different ways. The first mutant, lotus, shows a transition zone gap in gas-filled tube, and more precise analysis shows that the gap corresponds to a local absence of tube, although tube is present proximal and distal to the gap. The second mutant, wheezy, shows dramatic tube dilation in the transition zone. These mutants may thus have opposing effects on the addition of apical membrane within the transition zone: too little, resulting in a gap, in lotus mutants; and too much, resulting in a dilation, in wheezy mutants. We show that lotus encodes N-ethylmaleimide Sensitive Factor 2 (NSF2), a protein required for SNARE recycling (Zhao et al., 2011). This implies an especially stringent requirement for vesicle traffic in connecting the two tube types. Significantly, we find that the second mutant, wheezy, encodes Germinal Center Kinase III (GCKIII). The human orthologs of GCKIII are effectors of the protein encoded by the human vascular disease gene, Cerebral Cavernous Malformation 3 (CCM3), and are putative Golgi-resident kinases (Fidalgo et al., 2010). Patients suffering from cerebral cavernous malformations show gross dilations of cerebral capillaries, thus suggesting that CCM3/GCKIII play a conserved role in tubulogenesis in limiting diametric tube expansion. Mutations in lotus and in wheezy both point to a crucial role of apical membrane delivery in tube morphogenesis.

We next go on to show that Drosophila CCM3 has a loss of function phenotype identical to GCKIII, and that it interacts genetically with GCKIII. Interestingly, our results stand in contrast to a previous report suggesting a requirement for the genes in tracheal lumen formation (Chan et al., 2011). Further, we find ectopic localization of junctional proteins in CCM3-depleted or GCKIII mutant cells, and an over-accumulation of the apical determinant, Crumbs, in GCKIII mutant cells. In contrast, although Crumbs also accumulates in lotus/NSF2 mutant cells, it does not appear to be enriched in the lumenal membrane. Over-expression of Crumbs by itself induces formation of multiple tiny dilations throughout the terminal cell, but not a large transition zone tube dilation.

Nevertheless, knockdown of crumbs in GCKIII mutants strongly suppresses the large local dilation defect. Similarly, we find that mutations in lotus (NSF2), that cause mislocalization of Crumbs, are epistatic to GCKIII. We also find that knock-down of the essential septate junction scaffold, Varicose (a MAGUK protein orthologous to human PALS-2), suppresses the transition zone dilation defect associated with GCKIII mutants. These data suggest that it is the inappropriate increase of septate junctions in combination with over-accumulation of Crumbs that confers a transition zone dilation defect. These studies of transition zone tube morphogenesis have direct relevance to human development and disease, and provide important mechanistic insight into the basic biological question of how tubes of differing architecture connect to each other.

RESULTS

Two mutants affect tube morphology in the transition zone

In a collection of mutants that nearly saturates the third chromosome for tracheal morphogenesis genes (Ghabrial et al., 2011), we were able to identify only 2 loci with transition zone-specific terminal cell tubulogenesis defects. Terminal cells mutant for lotus displayed a gap in the gas-filled transition zone tube (compare Figure 1C–C″ and D with 1E-E″ and F; for other lotus phenotypes see Figure S1) (Ghabrial et al., 2011). In contrast, terminal cells mutant for wheezy displayed a transition zone tube dilation defect (Figure 1G–G″; H; for other wheezy phenotypes see Figure S1).

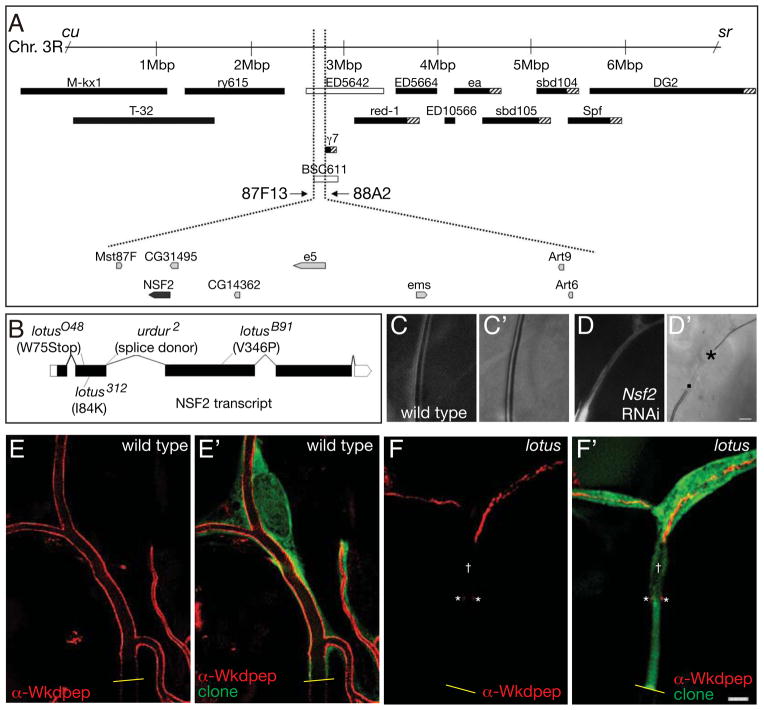

lotus encodes Drosophila NSF2

Mapping of lotus (Figure 2A and Experimental procedures) defined a 180 kb interval that included only 7 candidate genes: art9, art6, CG14362, CG31495, Mst87F, NSF2, and e5. We sequenced these on lotus mutant chromosomes and identified single point mutations for each allele of lotus in the N-ethylmaleimide Sensitive Factor 2 (NSF2) primary transcript; these resulted in predicted mis-sense (312, B91) and nonsense mutations (O48) as well as a splice donor mutation (urdur2) (Figure 2B). We confirmed gene identity by testing the ability of terminal cell-specific RNAi knockdown of NSF2 to phenocopy lotus (Figure 2C–D′; 52% of terminal cells showed a gap defect, n = 80). Drosophila has two NSF orthologs, with NSF1 being neuron-specific (Golby et al., 2001; Sanyal and Krishnan, 2001). NSF is an AAA protein required for SNARE recycling, and therefore ought to affect all aspects of SNARE-dependent transport, but surprisingly shows an uncommon and specific transition zone defect in terminal cells.

Figure 2. The cloning and phenotypic characterization of lotus.

(A)Meiotic recombination mapping placed lotus between the visible recessive markers curled (cu) and stripe (sr) on the right arm of the third chromosome. Complementation tests against an overlapping set of chromosomal deletions (black boxes indicate the cytological extent of the deletion in strains that complement, white boxes strains that uncover; hashed boxes indicate regions of ambiguity in the deletion breakpoint) defined a lotus candidate region between 87F13 and 88A2. Mutations in urdur map to this region, and fail to complement lotus. However, the molecular identity of urdur was unknown. We analyzed the 8 genes in the candidate region and identified single nucleotide changes in NSF2 (B) for all of the alleles of lotus and urdur examined. The lotusO48 allele is predicted to be a molecular null allele of NSF2, and was used hereafter for the phenotypic analysis of lotus. We were able to confirm the identify of lotus by phenocopying the third instar transition zone gap defect by specifically knocking down NSF2 with pantracheal RNAi (compare C, C′ with D, D′). In (C and D) the cytoplasm of the terminal cell transition zone is shown, while in (C′ and D′) the corresponding brightfield image reveals the presence or absence of gas-filled tube (in D′, . marks the stalk cell proximal portion of the terminal cell transition zone lack gas-filled tube, while * marks the resumption of gas-filled tube at the distal end of the transition zone. We note that the cell size and tube diameter of lotus mutants is severely reduced as compared to wild type – this aspect of the RNAi phenotype is also readily visible in homozygous mutant cells as compared to wild type (compare E with F). To examine the transition zone tube at higher resolution, mosaic third instar larvae were filleted, fixed and stained with anti-GFP antibodies (green) to identify mutant clones and with α-Wkdpep antibodies (red) to mark the lumenal membrane. Images were deconvolved using Leica software. In control wild type clones (E, E′), lumenal membrane staining in the transition zone is uninterrupted (although the level tapers off toward the junction with the stalk cell – junction with stalk cell marked with yellow line). In contrast, in lotus mutant clones (F, F′) lumenal staining is not continuous. In some instances (as shown) staining reveals a tube that begins several microns distant from the point (yellow line) at which the terminal cell contacts the neighboring stalk cell, while at other times tube extended from the stalk cell junction a few microns into the terminal cell (not shown), before ending only to resume more distally. We also note a region of several microns in which a lumenal space (†) appears to be detected by exclusion of GFP, but which lack α-Wkdpep staining. Interestingly puncta of lumenal membrane staining (*) are present at the proximal end of this region, perhaps suggestive of tube loss or of a deficit in tube growth relative to the increase in terminal cell size. Smaller areas of tube discontinuities could also be discerned at other positions in the terminal cell. Scale bars = 5 microns. See also Figure S4.

Characterization of the transition zone in lotus terminal cells

The phenotype of lotus transition zone tubes could reflect a defect in gas-filling for that portion of the tube, or absence of the tube. In this context, it should be noted that tracheal tubes are thought to gas-fill by forcing dissolved gas out of solution (Tsarouhas et al., 2007). Thus, discontinuous isolated tubes in terminal cells could be gas-filled even in the absence of a physical connection that would allow diffusion from the external environment. Further complicating the analysis, we found that while 35% of lotusO48 terminal cells displayed the gap defect described above, the remaining 65% of cells lacked gas-filling in all terminal cell tubes (n = 20). We examined homozygous mutant lotus first instar larvae, and found that the initial formation and gas-filling of the terminal cell tubes occurred normally (Figure S4). We next asked whether the defect is in maintenance of gas-filling, maintenance of tube connectivity, or both. In control wild type clones in third instar larvae, a GFP-excluding lumen could be detected; therefore we asked if tubes could be detected in lotus cells by GFP exclusion, and also assayed for the presence of tube using a marker of terminal cell lumenal membrane (α-Wkdpep; (Schottenfeld-Roames and Ghabrial, 2012)) (Figure 2E–F′). We found that ~70% of lotusO48 mutant terminal cells show a discontinuous tube that is disrupted in the transition zone (n = 13). These data suggested that tube in the transition zone is uniquely sensitive to defects in vesicle trafficking, indicating a key role for membrane fusion in the maintenance of a connection between seamed and seamless tubes, as well as in their gas-filling. The affected trafficking events may be those for which one or more required SNARE proteins are especially limiting.

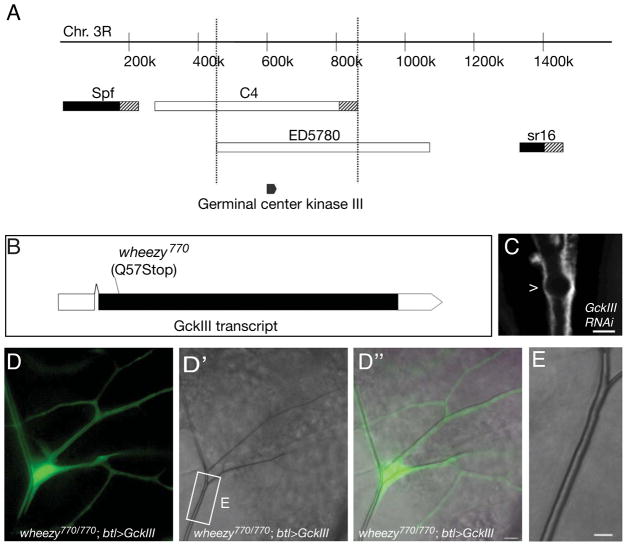

wheezy encodes the Drosophila Germinal Center Kinase III

Complementation tests against overlapping chromosomal deficiency strains defined a wheezy candidate interval spanning ~50 genes (Figure 3A). Of these candidate genes, GCKIII was of particular interest because of the vascular defects associated with the vertebrate orthologs (Zheng et al., 2010), and because of the reported Golgi localization of GCKIII (Preisinger et al., 2004), which would be consistent with a role in regulation of vesicle trafficking, a process our recent data suggest to be critical to seamless tube morphogenesis (Schottenfeld-Roames and Ghabrial, 2012). The GCKIII gene was sequenced, and the wheezy770 allele was found to be a molecular null for GCKIII, as we identified a nonsense mutation predicted to terminate the protein after 56 amino acids (Figure 3B). We confirmed gene identity by recapitulating the wheezy mutant phenotype (Figure 3C) in a substantial fraction of terminal cells with pan-tracheal knock-down of GCKIII. As was true in our mosaic analysis with wheezy, only terminal cells showed GCKIII RNAi-induced defects (data not shown). While the most prominent defect (and the focus of our studies) was the transition zone tube dilation, we did note additional terminal cell defects consistent with a general effect on the lumenal membrane (as described in Figure S1). In a final proof that wheezy encodes Drosophila GCKIII, we were able to rescue all tracheal defects observed in wheezy mutants with tracheal-specific expression of a wild type GCKIII cDNA (Figure 3D–E).

Figure 3. Molecular identification of wheezy and transgene rescue.

Complementation tests against overlapping chromosomal deletion strains spanning the right arm of the third chromosome were carried out to map wheezy. Two partially overlapping deficiency strains – Df(3R)C4 and Df(3R)ED5780 – uncovered wheezy. Within the ~ 400 kb region defined by the deletion breakpoints, we identified Germinal Center Kinase III (GCKIII), as a likely candidate. Upon sequence analysis, wheezy was found to have a single nucleotide change in the GCKIII coding sequence that introduces an early stop (B). We expect that the wheezy770 allele is molecularly null for GCKIII, since the encoded protein would be truncated after 56 amino acids and would therefore lack a kinase domain. Pan-tracheal RNAi knockdown of GCKIII was able to phenocopy the wheezy transition zone tube dilation (C, dilation marked with >). A UAS-wheezy transgene generated using a wild type GCKIII cDNA rescued the wheezy mutant phenotype upon pan-tracheal expression (D–E). (D) Shows a fluorescent image of a positively marked (GFP, green) wheezy mutant terminal cell clone that is also expressing a wild type GCKIII transgene under control of the breathless-Gal4 driver. (D′) Shows the bright field image of the same clone and (D″) shows a merged image. The terminal cell transition zone (from stalk cell:terminal cell interface to terminal cell nucleus, white rectangle) looks normal. In (E), the transition zone (indicated by rectangle in D′) is shown enlarged; note the absence of the dilation defect characteristic of wheezy mutant terminal cells. All images depict third instar larvae. Scale bars = 5 microns. See also Figure S3 and Table S1.

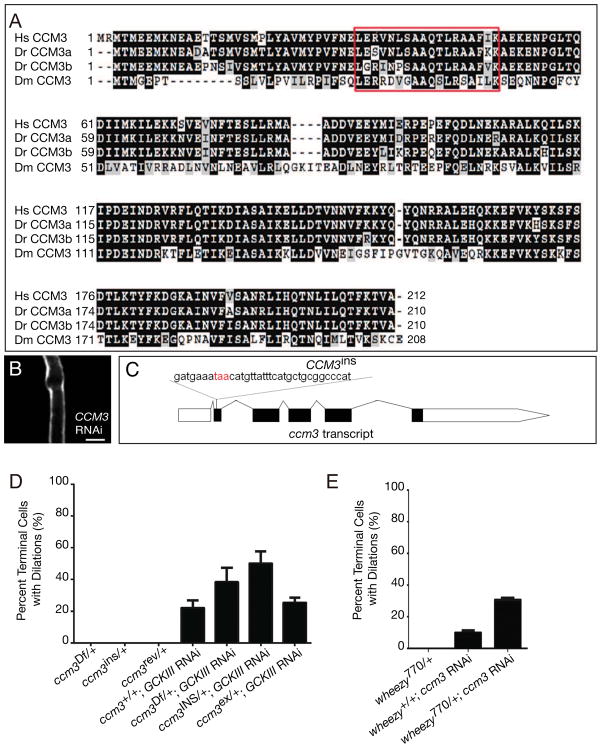

Knockdown of Drosophila CCM3 (CG5073) phenocopies wheezy

The three vertebrate GCKIII family members (Mst4, Stk24, Stk25) bind in vitro to Cerebral Cavernous Malformation 3 (CCM3/PDCD10) (Voss et al., 2009; Zheng et al., 2010). Mutations in CCM3 are causative for a vascular disease in humans characterized by gross dilation of cerebral capillaries, and CCM3 has been shown to have an essential role in endothelial cells for normal vascular development (Bergametti et al., 2005; Chan et al., 2011; Guclu et al., 2005; He et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2008; Pagenstecher et al., 2009; Voss et al., 2009). While human disease has not been linked to mutations in GCKIII proteins, knock-down of multiple stk24 and stk25 family members in zebrafish (Zheng et al., 2010) confered cardio-vascular defects identical to those seen with knockdown of both zebrafish CCM3 orthologs (Voss et al., 2009). Since CCM3 is well conserved in Drosophila (Figure 4A), and the Drosophila CCM3 and GCKIII proteins bind (Chan et al., 2011), we sought to determine whether loss of CCM3 would phenocopy wheezy or show the lumenization defect previously reported in the tracheal system for RNAi of GCKIII and CCM3 (Chan et al., 2011). Indeed, we found that pan-tracheal knockdown of CCM3 caused transition zone tube dilation (Figure 4B). We note that the CCM3 dilation is somewhat less extensive than that seen with GCKIII, this could reflect a maternal contribution of CCM3 or incompleteness of knockdown. We next tested for genetic interactions between wheezy (GCKIII) and CCM3 using a chromosomal deletion for CCM3 (Df(3R)EXEL6174; for convenience, referred to here as CCM3Df), as well as new CCM3 alleles we generated by mobilization of a P element in the gene (P{EPg}CG5073HP36555, Experimental procedures, Figure 4C). We found that heterozygosity for CCM3 enhanced the penetrance of the GCKIII RNAi phenotype, and that heterozygousity for wheezy likewise enhanced the penetrance of the CCM3 RNAi phenotype (Figure 4D, E). Together, these data demonstrate conservation of the CCM3-GCKIII pathway in tube morphogenesis between flies and man.

Figure 4. CCM3 knockdown and GCKIII/CCM3 genetic interaction.

The Drosophila genome contains a single well-conserved (47% identity, 67% similarity) CCM3 ortholog (A). A stretch of 18 amino acids (red box) identified as essential for interaction with GCKIII (Voss et al., 2009) show 56% identity and 72% similarity to the human protein. Pan-tracheal knockdown of CCM3 conferred a transition zone tube dilation defect very similar to that seen with loss of GCKIII activity (B, transition zone dilation indicated by >). A strain with a P element insertion in the second intron of CCM3 was obtained. The P element was mobilized and two derivatives were recovered: (C) CCM3ins, in which P element excision left behind a small insertion introducing extraneous coding sequence and an in-frame stop codon; and CCM3rev, a precise excision (revertant) of the P element. Both of these derivatives retain lethal mutations elsewhere on the right arm of chromosome 3. We tested the ability of these alleles to enhance the penetrance of the GCKIII RNAi tube dilation (D). Conversely, mutation of a single copy of GCKIII was tested for the ability to enhance the penetrance of the CCM3 RNAi tube dilation (E). None of the chromosomes tested displayed a haplo-insufficient transition zone defect. The mean of three trials ± SEM are shown in D and E. All larvae were scored at third instar. See also Figure S3 and Table S1.

How loss of CCM3 or GCKIII activity causes a tube dilation defect has not been clear. It hasbeen suggested that phosphorylation of Moesin may be the key event downstream of GCKIII kinase activity in endothelial cells (Zheng et al., 2010); we therefore sought to determine whether moesin played a key role in wheezy transition zone tube dilation. First, we found that moesin loss of function does not affect transition zone tube in an otherwise wild type background (data not shown). Second, expression of a phospho-mimetic isoform of Moesin in GCKIII mutant terminal cells does not suppress the transition zone tube dilation (data not shown). Lastly, in mosaic larvae, we found that phospho-Moesin levels appear to be substantially higher in wheezy mutant terminal cells than in neighboring heterozygous cells, the opposite of the expected outcome were Moesin a target of GCKIII kinase activity (Figure S2). Interestingly, p-Moe appears to be especially enriched in the transition zone, in association with dilated tube (45%, n = 11). These data are consistent with published results that Slik is the Ste20K responsible for phosphorylation of Moesin in epithelia (Hughes et al., 2010), and lead us to look elsewhere for candidate GCKIII substrates.

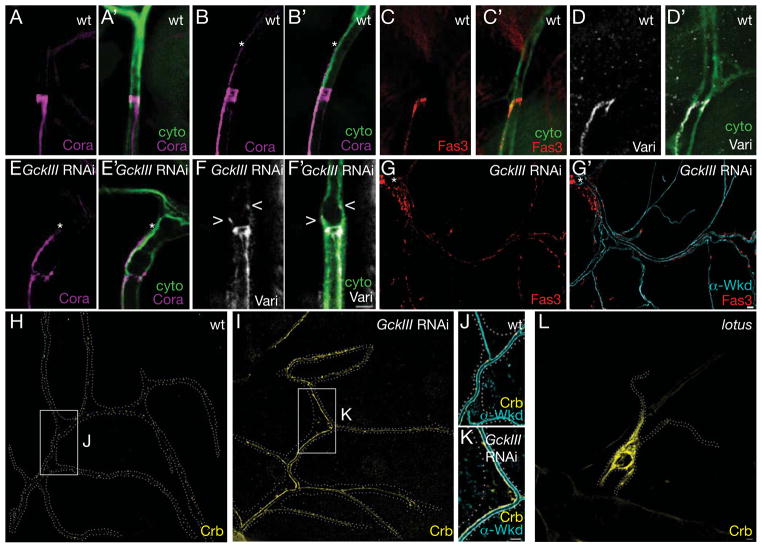

Defects in the abundance and localization of junctional and apical proteins

In the embryonic tracheal system, septate junctions (functional equivalent to vertebrate tight junctions) have been suggested to line the intercellular connection between the terminal cell and its neighboring stalk cell, and also to extend in from the intercellular junction into the terminal cell transition zone (Samakovlis et al., 1996a). Because of the transition zone defects of lotus and wheezy, we wished to determine whether the transition zone junctions were perturbed. In contrast to our expectations, we found that in wild type third instar larvae (Figure 5A–D′), septate junctions extended into the transition zone of only ~4 % of terminal cells (n = 49). We interpret this outcome as suggesting that a remodeling of the junctional complexes had occurred during development. When we went on to examine terminal cells depleted of GCKIII by RNAi, we found septate junctions appeared to extend into the transition zone at a much higher frequency than in wild type (Figure 5E, E′) – 32% by Varicose staining (n=25) and 42% by Fas3 (n=64) or Coracle (n=45) staining, with patchy punctate junctional staining (Figure 5F, F′) detected in an additional ~ 25% of cells. While ultrastructural analysis would be required to definitively show the ladder-like organization of septate junctions, we find that co-staining experiments (Figure S3) for Vari and Fas3 showed identical or largely overlapping distribution in 100% of cells (n = 17), suggesting the maintenance of functional septate junctions in the transition zone. Furthermore, we found that septate junction proteins were present in foci far from the transition zone (Figure 5G, G′); these foci showed only partial co-staining for Fas3 and Vari. The ectopic puncta of junctional protein may represent protein undergoing vesicular trafficking; Tiklova and colleagues (Tiklova et al., 2010) show that dispersed basolateral septate junction proteins are trafficked through an endocytic pathway prior to their assembly in mature septate junctions. However, we were unable to detect substantial co-localization between isolated Fas3 puncta and Lamp-1, FYVE-GFP, Rab4, 5, or 11 (Figure S3). These data suggest that ectopic Fas3 may be present at the basolateral membrane at steady state, perhaps reflecting a deficit in endocytosis or in the initial targeting of Fas3 containing vesicles. Similar defects were seen for septate junctions in CCM3 RNAi animals (Figure S3). In contrast, septate junctions appeared largely similar to wild type in lotus terminal cells (Figure S4). Because it has been suggested that autocellular tubes in the terminal cell transition zone may derive from the neighboring stalk cell, which might insert its tube into the terminal cell like a finger poking into a balloon (Uv et al., 2003), we tested whether the septate junctions we detect are autonomous to the terminal cell, and found that they are (Figure S3).

Figure 5. Ectopic septate junctions and apical membrane in wheezy mutant cells.

We examined the distribution of septate junction proteins in wild type terminal cells (A–D′), and in terminal cells in which GCKIII had been knocked down by RNAi (E–G′). We found that in the vast majority of terminal cells, septate junctions do not extend into the terminal cell (A, C, D); however, in ~4% of terminal cells a line of septate junctions extending into the terminal cell towards nucleus, similar to that reported for embryonic terminal cells, was detected (asterisk marks the end of a line of septate junction staining extending into the terminal cell in B). This pattern of staining was observed with Coracle (magenta), Fas3 (red) and Varicose (white). In GCKIII RNAi terminal cells showing a dilation defect, a line of septate junction staining (asterisk as in B) was detected extending into the cells (E, E′) at frequency almost an order of magnitude higher than wild type. Additional terminal cells displayed punctate septate junction staining (marked by < and > in F, F′). Lastly, short discontinuous patches of septate junction could be observed 10s or 100s of microns away from the transition zone (G, G′; asterisk marks the transition zone dilation – upper left corner). (G′) Fas3 puncta appeared present at the basolateral membrane, rather than at the apical membrane marked by α Wkd staining (cyan). (H) Discrete puncta of Crumbs decorated the lumenal membrane of wild type terminal cells, but in GCKIII-depleted (RNAi) terminal cells (I), Crumbs levels appeared elevated and its distribution altered to more evenly coat the lumenal membrane (J and K, corresponding to areas marked by white rectangles in H and I, respectively). In lotus mutant terminal cell clones (L), in contrast, Crumbs no long appeared restricted to the lumenal membrane. For (H–L), cell outlines (white dots) were traced and superimposed on the fluorescent images. All images depict third instar larvae. Scale bars = 5 microns. See also Figure S5.

In previous work (Schottenfeld-Roames and Ghabrial, 2012), we found that Crumbs-GFP expressed as a functional knock-in allele (Huang et al., 2009), is detected in discrete puncta throughout the membrane that surrounds the lumen of seamless tubes in terminal cells (Figure 5H). In a second study, we determined that a mutation causing multiple seamless tube micro-dilations was associated with over-accumulation of Crumbs on the lumenal membrane (Schottenfeld-Roames and Ghabrial, submitted). We note that multiple micro-dilations can be detected in wheezy terminal cells upon staining with an apical membrane marker (also observed with CCM3 RNAi, Figure S1). This led us to explore whether elevated Crumbs levels might also be involved in the wheezy and CCM3 transition zone dilations. In terminal cells depleted of GCKIII by RNAi, Crumbs-GFP levels were dramatically increased (Figure 5I), and the protein accumulated more uniformly along the lumenal membrane (compare 5J, K). In contrast, we noted that in lotus mutant cells, Crumbs accumulated to high levels but was no longer restricted to the lumenal membrane (Figure 5L). In double mutants, we observed that lotus was epistatic to wheezy, consistent with the possibility that apical Crumbs accumulation may be required for tube dilation (Figure 6A–C) – in the double mutant, Crumbs localization was as in lotus single mutants (Figure S5). As might be expected, in ~70% of terminal cells (9/13) no tube was present in the transition zone as a consequence of loss of lotus (Figure 6C; apical membrane staining not shown); however, in the remaining 30% of cells (4/13) with a continuous transition zone tube we observed suppression of the wheezy tube dilation (Supplemental Movie).

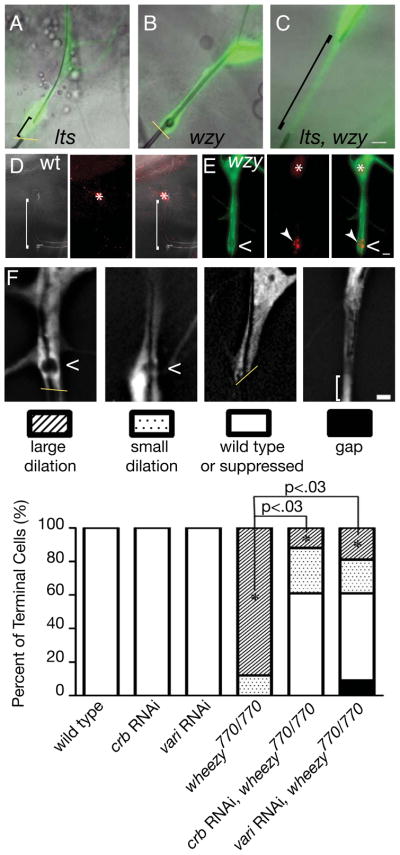

Figure 6. Genetic suppression of wheezy transition zone tube dilations.

In epistasis experiments, we found that lotus, wheezy double mutant terminal cell clones (C, compare to single mutant cells in A and B) show the lotus mutant phenotype, perhaps because Crumbs protein is mislocalized in the double mutant cells (Figure S5). Staining of endogenous Rab11 in wild type (D) and wheezy mutant (E) terminal cells suggests that there is a dramatic enrichment of Rab11 in the transition zone upon loss of GCKIII activity. Mosaic animals were generated and the homozygous mutant wheezy clone (E) is marked with GFP (green), while neighboring heterozygous control terminal cells are GFP negative (D). In heterozygous control cells, tube lumens were visualized by autofluorescence in the UV channel (white), and the transition zone is indicated by ([). Control terminal cells were identified by nuclear DsRED2 expression and by tube morphology. Dilation indicated by <, nucleus by *, and Rab11 by arrowhead. To directly test whether knockdown of Crumbs, or of septate junctions, could suppress the transition zone tube dilation defect of wheezy, we carried out similar epistasis experiments. Terminal cell transition zone tubes were classified into one of 4 categories (F): large dilation, indicating no modification of the wheezy tube dilation defect; small dilation, indicating a partial suppression of the defect, wild type or suppressed – indicating no dilation or a complete suppression of the transition zone dilation; and gap, indicating a discontinuous tube defect similar to that seen in lotus terminal cells. Dilations are indicated by <; the terminal cell stalk cell interfaces (if within field of view) are indicated by a yellow line; and the extent of the transition zone tube gap is indicated by a bracket. Genotypes of terminal cell clones shown in F are (left to right): wheezy770/770; wheezy770/770 with RNAi knockdown of crumbs; wheezy770/770 with RNAi knockdown of crumbs; wheezy770/770 with RNAi knockdown of varicose. Expression of crb or vari RNAi in wild type terminal cells with the btl-Gal4 driver at 25 °C did not alter the normal morphology of transition zone tubes, but their expression in wheezy mutant cells dramatically suppressed the dilation defect (F). To compare wheezy clones to wheezy clones with crumbs or varicose RNAi, a P value was calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. The fraction of transition zone tubes with large dilations was scored, and the mean of the three trials was used. For the histogram plotted in E, the total number of terminal cells scored were as follows: n = 25 (wt); 41 (crb RNAi); 38 (vari RNAi); 51 (wheezy770 clones); 55 wheezy770 clones with crb RNAi) and 48 (wheezy770 clones with vari RNAi). All images depict third instar larvae. Scale bars = 5 microns. See also Figure S6 and Movie S1.

Depletion of crumbs suppresses the wheezy tube dilation phenotype

Importantly, over-expression of Crumbs by itself does not give rise to the large transition zone dilation observed in wheezy mutant terminal cells (Schottenfeld-Roames and Ghabrial; submitted); however, we wondered if, as suggested by the lotus-wheezy epistasis results, it might nevertheless contribute to the transition zone tube dilations. We asked if Crumbs depletion might suppress the transition zone dilation defect in wheezy mutant cells. We found that knockdown of crumbs by RNAi in wheezy mutant terminal cells completely suppressed the transition zone dilation defect (Figure 6F) in 61% of terminal cells and appeared to reduce the severity of the dilation in an additional 27% of cells (n = 55). These data imply that apical accumulation of Crumbs is required for the dilations observed in wheezy mutants, but is not in itself sufficient to cause them. The mechanism responsible for Crumbs accumulation in wheezy mutant cells is not yet clear; however, we have found a substantial enrichment of Rab11 within the transition zone, associated with dilated tube (59% of terminal cells, n = 32; Figure 6D, E). This suggests that GCKIII affects the spatial distribution of the recycling endosome compartment, and may regulate Crb levels via vesicular trafficking.

Depletion of varicose suppresses the wheezy tube dilation phenotype

We next asked whether the increase in septate junctions in wheezy mutants contributed to the transition zone dilation defect. To do so, we tested whether depletion of Varicose, a MAGUK protein required for septate junction assembly and function (Bachmann et al., 2008; Moyer and Jacobs, 2008; Wu et al., 2007), was able to suppress the wheezy tube dilation defect. We found that transition zone tube dilation was completely suppressed in 52% of terminal cells and partially suppressed in another 20%, while an additional 9% of cells actually showed the discontinuous tube (“gap”) defect characteristic of lotus (n=48) (Figure 6F). That knockdown of varicose in a wheezy mutant background can give rise to the full spectrum of transition zone tube phenotypes suggests that the effects of knockdown are dosage sensitive. Consistent with a dosage sensitivity for varicose, we note that the Leptin lab was unable to recover homozygous mutant tracheal cell clones deficient for varicose (Baer, 2007). Under the RNAi conditions we used, depletion of varicose in an otherwise wild type background did not cause an obvious tubulogenesis defect, although we could observe altered localization of Fas3 (Figure S6). We interpret these results as implicating septate junctions in targeting of membrane addition to the transition zone tube. Strikingly, in wheezy terminal cells in which varicose knockdown suppressed the transition zone dilation, the presence and number of seamless tube micro-dilations was not altered (Table S2); this implies that the large dilations resulting from loss of wheezy function reflect a specific transition zone requirement for GCKIII.

Discussion

In the terminal cell “transition zone,” seamed and seamless tubes must connect. We found that during development, remodeling of cell junctions reduced tube type complexity in the transition zone, such that by third instar only seamless tubes are still present in the majority of terminal cells. How the tubes connect initially has been an outstanding question in the field for more than a decade, and whether, or how, transition zone tubes remodel over developmental time has not previously been addressed. In this manuscript, we describe several mutations that disrupt tube morphogenesis in the terminal cell transition zone. The mutants fall into two classes which appear to act in opposing manners: in the case of mutants like lotus, there appears to be a deficit of apical membrane addition to the growing tube within the transition zone, most frequently resulting in a failure to make a continuous tube. In the case of mutants such as wheezy, too much apical membrane is added to the transition zone tube, resulting in a grossly dilated appearance. Our molecular genetic characterization of the genes is consistent with this hypothesis as lotus encodes a factor required for membrane traffic and wheezy encodes a putative Golgi-resident kinase that we show is required for restricting the accumulation of apical and junctional proteins. In this context, it is important to consider that secretion of specific cargo into the tube lumen during embryonic tracheal development is dependent upon septate junctions (Wang et al., 2006); perhaps an increase in transition zone septate junctions promotes enhanced targeting of vesicles to the lumenal membrane. However, the existence of septate junctions in the transition zone by itself does not appear to lead to tube dilation since ~4% of wild type third instar terminal cells have septate junctions in the transition zone, but do not have dilations. This, together with the inability of Crumbs over-expression to cause transition zone dilations, and with the suppression of such dilations by knockdown of crumbs or of varicose, leads us to propose that both ectopic septate junctions and increased accumulation of apical polarity proteins are required for transition zone tube dilation. Our study provides genetic and molecular insight into the process of junctional remodeling and tubulogenesis in the transition zone.

We have determined that wheezy encodes GCKIII, the only known downstream effector of CCM3, a protein mutated in human vascular disease characterized by grossly dilated, leaky capillaries. It therefore becomes important to ask whether our insights into the cellular basis of GCKIII/CCM3 deficiency are compatible with what is known from patient samples and vertebrate CCM models. In excised CCMs, staining of apical polarity proteins and junctional proteins has not been reported, but ultrastructural analyses suggest that endothelial cells lack functional tight junctions, and in mouse models, lymphatic vessels show gaps between endothelial cells or show shorter intercellular junctions (Clatterbuck et al., 2001; Kleaveland et al., 2009). On the other hand, EM analysis of vessels from endothelial-specific CCM3 knockout mice showed tight junctions were present and did not detect any gaps between endothelial cells (Chan et al., 2011). It is not clear how to reconcile these data, although it is possible that loss of CCM1 and 2 cause tube dilation by a mechanism that is distinct from that seen with loss of CCM3, as suggested by Chan and colleagues (Chan et al., 2011). In the Drosophila tracheal system, we see a clear and dramatic increase in apical polarity protein accumulation, and a convincing defect in remodeling of septate junctions; this suggests that a re-examination of endothelial tight junctions and an initial study of apical polarity determinants in vertebrate CCM models should be a high priority. Indeed, extant data hint that such studies could be of great value. For example, mutations in the zebrafish orthologs of Stardust and Yurt (physical interactors and regulators of Crumbs in Drosophila) have cardiovascular defects (Jensen et al., 2001; Jensen and Westerfield, 2004). Moreover, remodeling of endothelial cell junctions during angiogenesis, as cells change neighbors and as the tubes they comprise change architectures, is likely to be critical to the formation of functional tubes. That terminal cells are the only tracheal cell type affected by loss of CCM3 or GCKIII activity is striking, and may be directly relevant to human disease given that ~30% of cells comprising capillaries in the cerebral cortex have an analogous cellular architecture, the so-called “seamless” endothelial cells (Bar et al., 1984). In addition, we note that the cellular architecture of endothelial tip cells that lead outgrowth of the zebrafish intersomitic vessels is dynamic: these cells often form seamless tubes, but sometimes appear to make tubes of mixed auto-cellular and seamless character (like fly terminal cells), and at other times appear to contribute to multi-cellular tubes (Blum et al., 2008; Herwig et al., 2011). Given the dynamic nature of tight junctions during angiogenesis, defects in junction remodeling such as those we see with wheezy mutants in the Drosophila tracheal system, might be expected to give rise to leaky vessels composed of endothelial cells that are not properly attached to each other.

The precise function of CCM3 and GCKIII during angiogenesis is not clear. Recently Chan and colleagues have suggested a requirement for the CCM3 pathway in lumen formation (Chan et al., 2011) while Zheng and colleagues (Zheng et al., 2010) have suggested that the pathway regulates cell junctions via phosphorylation of Moesin. Our data conclusively show that neither model is consistent with the observed effects of loss of the CCM3/GCKIII pathway in the fly tracheal system; we discuss each model in the context of our data below.

The lumen formation model of Chan et al. is built upon the outcome of two sets of experiments: tubulogenesis assays of CCM3- or GCKIII-depleted endothelial cells and RNAi studies in the Drosophila tracheal system. The tubulogenesis assays have been used to great effect by Davis and colleagues, allowing them to identify a number of genes required for endothelial lumen formation (Bayless et al., 2000; Fisher et al., 2009; Koh et al., 2009); however, it is important to appreciate that the endothelial cells in this assay must do more than simply lumenize, they must also migrate, remodel the matrix, and organize and re-organize cell:cell contacts. Disruption in any of these pre-conditions for lumenization would also compromise tubulogenesis. Thus, should the junctional remodeling defects observed in the fly tracheal system also pertain to endothelial cells depleted for CCM3 or GCKIII, those remodeling defects might be sufficient to block lumenization in the in vitro assays. Additionally, the fact that patient CCMs are dilated capillaries rather than lumenless capillaries would also seem to argue against this model.

We note that our data for GCKIII and CCM3 in the Drosophila tracheal system stand in contrast to the findings of Chan et al (Chan et al., 2011). Unlike Chan et al., we find tube dilation to be the primary consequence of loss of CCM3 or GCKIII function. The fully penetrant transition zone defect we observed in wheezy mutant flies is compelling, and is directly supported, in our hands, by RNAi experiments targeting either GCKIII or CCM3, including with RNAi transgenes employed by Chan and colleagues (Table S1). Consistent with the findings of Chan et al., we do observe defects in terminal cell gas-filling (but not in other tracheal cell tubes by mosaic analysis using a null allele of GCKIII). However, we find that the lack of observable gas-filled tubes is not due to failure in tube formation, as suggested by Chan et al, but rather due to a failure in liquid clearance. Indeed, we readily detected liquid-filled tubes in the knocked-down cells (Figure S1). Importantly, our data argue that CCM3 and GCKIII are not required for making a lumen, but instead are required to prevent inappropriate trafficking of junctional and apical proteins.

We have also addressed the Zheng et al. model that phosphorylation of Moesin is the essential function of the CCM3/GCKIII pathway during tubulogenesis. Moesin is the only ERM (Ezrin-Radixin-Moesin) family member in Drosophila, and we find that phosphorylation of Moesin in the tracheal system is not compromised by loss of CCM3 or GCKIII (in fact it is elevated). These data suggest that the essential target of GCKIII kinase activity is not Moesin, but another protein yet to be identified. Going forward, it will be of great interest to determine what proteins are regulated by GCKIII kinase activity in the tracheal system, and to test whether vertebrate orthologs of these factors are required during angiogenesis.

Experimental Procedures

Fly strains

lotus312, urdur2, and wheezy770 alleles were described (Ghabrial et al., 2011; Kennison and Tamkun, 1988). lotusO48 and lotusB91 were isolated in an EMS mutagenesis screen (below). Tissue specific knockdown was with the GAL4/UAS system. Driver lines used were btl-GAL4 (pan-tracheal) and srf-GAL4 (terminal cell; a gift from Mark Metzstein); and RNAi responder strains were VDRC939 (Fas3), VDRC7743 (NSF2), VDRC49559, VDRC49558, VDRC107158 (GCKIII), VDRC46548, VDRC106841, VDRC109453 (CCM3), VDRC24157 (varicose) and VDRC39177 (crumbs). A full-length cDNA of GCKIII was cloned into pUAST using EcoRI and KpnI, and transgenic flies were generated (Genetic Services Inc). In rescue experiments UAS-GCKIII was driven by btl-GAL4. UAS-GFP-Lamp1 was a gift from Helmut Kramer. The crumbs-GFPA stock was a gift from Yong Hong (Huang et al., 2009). UAS-YFP-Rab4, UAS-YFP-Rab5, UAS-GFP-myc2xFYVE, urdur2, P{EPg}CG5073HP36555, and deficiency strains were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center.

Allele screens

Additional alleles of lotus were isolated in an EMS mutagenesis screen. btl>GFP; FRT2A, FRT82B males were mutagenized, and ~2000 F1 males with lethal mutations were generated. Alleles of lotus were identified using a lotus312 tester strain, and validated by tracheal phenotype.

Generation of CCM3 excision alleles

Male P{EPg}CG5073HP36555 flies were crossed with virgins carrying Δ2–3 transposase. 200 independently derived chromosomes were recovered that had lost the w+ minigene marking the P element; these were balanced over TM3, Sb. Precise and imprecise excision alleles was identified by complementation test with Df(3R)EXEL6174, and by sequence analysis. The presence of at least 2 lethal mutations on the right arm of chromosome 3 in the P{EPg}CG5073HP36555 stock precluded their use in analysis of homozygous mutant animals. Primers pairs used for PCR amplification and sequencing were: 5′-ATGGACTTCTGGTCGGTGAG-3′, and 5′-AATCGCAACTGGGTTCCTGC-3′; 5′-CAATCGTAAGTCCGTGGCTCTC-3′, and 5′-TCGTCCGTCTCCATAAATAGTTGC-3′; 5′-TCCAAGAAGTTCAGCACAACGC-3′, and 5′-AAAAGTGGGTCATCTCGGTCG-3′.

Mosaic analysis

Virgin hsFLP122; btl-Gal4, UAS-GFPor UAS-DsRed; FRT82BUAS -Gal80 (Lee and Luo, 2001) or UAS-GFP RNAi (Ghabrial et al., 2011) flies were crossed to males bearing the mutation of interest on an FRT82B chromosome. Embryos were collected 0–4 hours after egg lay, and subjected to a 38°C heat shock for 45–55 minutes to induce expression of FLP recombinase, and then allowed to develop at 25°C until third larval instar (L3). For wheezy clones in which Fas3 was knocked-down by RNAi: virgin hsFLP122; UAS-Fas3RNAi; FRT82B, Tub-Gal80 flies were crossed to male btl-Gal4, UAS-GFP; FRT2A, FRT82B, wheezy770/TM3Sb, Tub-Gal80. For wheezy clones with pan-tracheal varicose knock-down,: virgin hsFLP122; UAS-variRNAi; FRT2A, FRT82B, wheezy770/TM3Sb, Tub-Gal80 flies were crossed to male btl-Gal4, UAS-GFP; FRT82B, cu, UAS-GFP-RNAi flies. Larvae were mounted in 60% glycerol, killed by heating on a 70°C block for ~10 seconds, and examined with a Leica fluorescence microscope, or were filleted ventrally in ice cold PBS and processed for antibody staining as described below.

Sequence analysis

lotus, urdur or wheezy alleles were balanced over TM3, Sb, Ser, twi-Gal4, UAS -GFP (Bloomington). Homozygous mutant embryos were selected, and DNA was extracted using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). Amplicons covering all exons and splice sites were and sequenced. Primers: NSF2 TACACACACGCAATGCCGAACAGG and TCTCACTACCGCTATGCTATGAACG; GGTTCTCGGTTTATCTCGGACG and TGGCTTCTGATTCACCCACG; CCTCGCTGTAAAAACGCTGG and AAAGTCACGCATCCGCTTGGTGTG; GAGTTCAATGCGATTTTCCGAC, and GCAGTTTTTCCATAGCCTCCG; CCAGTTGAGTGATTTCCCATTCG, and CGGTTCTGTGTATTAGGCTTGAAGG; CAAAGAACTTCAGTGGCG-, and GCGGTTGCTTTTTCAGTAG. GCKIII were: CTTTTCGGAACTGCTAACG and CCATAACTTGGTGCCCTT; GGAGTAACAAGGAAACCCG and GGGTGGATTGTTCTTGGGGA; AAGGGCGACGAAAGTGAGAC and CGTTTCAGTTTGTGTTGTCTCG; GAACAACTTCCTCTTCCCC and GGGTTCCTCATTTCCAATAAGG. For lotus312, a single nucleotide change was detected corresponding to a T-to-A transition, which caused an amino acid substitution in the conserved N domain of NSF2; for the lotusB91, a G-to-C nucleotide change was detected which caused a mis-sense mutation in the conserved D1 domain of NSF2; for lotusO48, a G-to-A transition was detected, that caused a non-sense mutation at the 75th codon of NSF2. In urdur2, a G-to-A mutation affecting the splice donor site of the second exon of NSF2 was detected. In wheezy770, a C-to-T transition caused a non-sense mutation in the 57th codon of GCKIII.

Penetrance of tube dilation defects

To compare among different genotypes, dorsal branch terminal cells from L3 larvae were scored. All dorsal branch terminal cells (~20) in five larvae were scored in each of three trials.

Immunohistochemistry

L3 larvae were dissected and fixed as described (Schottenfeld-Roames and Ghabrial, 2012). Primary antibody incubations were at 4°C overnight. Primary antibodies used were mouse α-Fas3 (DSHB; 1:50), mouse α-Coracle (DSHB, a cocktail of C566.9C and C615.16A, each at 1:500), rabbit α-Rab11 (a gift from Robert Cohen, 1:500), rabbit αVaricose (a gift from Elisabeth Knust; 1:500), Chicken α-GFP (Invitrogen; 1:500), Mouse-α-Phospho-ERM (Cell Signalling; 1:200), mouse α-RFP (Abcam; 1:1000) and rabbit α-Wkd (Schottenfeld-Roames and Ghabrial, 2012). Secondary antibody incubations were at room temperature for 1 hour. Alexa Fluor 488, 555 and 647 conjugated secondary antibodies were used (Invitrogen; 1:1000). Samples were mounted in aquapolymount (Polysciences, Inc), and images were acquired on a Leica DM5500 compound microscope. Z-stacks were captured for most images. Where possible, single Z images are shown. When deemed necessary for clarity, optimal focal planes (planes that bisect the tube) were merged to generate a montage of different Z series in the same x,y position – images that are montages are indicated in the figure legends.

Statistical Analysis

varicose and crumbs knockdown experiments were done in the background of wheezy or wildtype control mosaic larvae. No knockdown, or pan-tracheal knockdown using crumbs or varicose RNAi, was driven by breathless-Gal4. For each group (wild type 3R clone, no RNAi; wild type 3R clone, crumbs RNAi; wild type 3R clone, varicose RNAi; wheezy clone, no RNAi; wheezy clone, crumbs RNAi; wheezy clone, varicose RNAi), experiments were set up simultaneously in triplicate and the transition zone tube phenotype of all clones were scored (large dilation, small dilation, wild type/suppressed dilation, or gap). The fraction of transition zone tubes with large dilations was determined, and the mean of the three trials was used to calculate a P value by a two-tailed Student’s t-test, comparing wheezy clones to wheezy clones with crumbs or varicose RNAi.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Drosophila CCM3 and GCKIII are required to prevent terminal cell tube dilation

Ectopic septate junctions and proteins are found in CCM3 and GCKIII terminal cells

Apical determinant Crumbs is elevated at the lumen in CCM3 and GCKIII terminal cells

of crumbs, varicose, or lotus/NSF2 suppresses the GCKIII tube dilation defect

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Steve DiNardo, Mark Kahn, and Meera Sundarum, the members of the Ghabrial lab, and three anonymous reviewers for their comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bachmann A, Draga M, Grawe F, Knust E. On the role of the MAGUK proteins encoded by Drosophila varicose during embryonic and postembryonic development. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer MM, Bilstein A, Leptin M. A clonal genetic screen for mutants causing defects in larval tracheal morphogenesis in Drosophila. Genetics. 2007;176:2279–2291. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.074088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar T, Guldner FH, Wolff JR. “Seamless” endothelial cells of blood capillaries. Cell Tissue Res. 1984;235:99–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00213729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayless KJ, Salazar R, Davis GE. RGD-dependent vacuolation and lumen formation observed during endothelial cell morphogenesis in three-dimensional fibrin matrices involves the alpha(v)beta(3) and alpha(5)beta(1) integrins. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1673–1683. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65038-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergametti F, Denier C, Labauge P, Arnoult M, Boetto S, Clanet M, Coubes P, Echenne B, Ibrahim R, Irthum B, et al. Mutations within the programmed cell death 10 gene cause cerebral cavernous malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:42–51. doi: 10.1086/426952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum Y, Belting HG, Ellertsdottir E, Herwig L, Luders F, Affolter M. Complex cell rearrangements during intersegmental vessel sprouting and vessel fusion in the zebrafish embryo. Dev Biol. 2008;316:312–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AC, Drakos SG, Ruiz OE, Smith AC, Gibson CC, Ling J, Passi SF, Stratman AN, Sacharidou A, Revelo MP, et al. Mutations in 2 distinct genetic pathways result in cerebral cavernous malformations in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1871–1881. doi: 10.1172/JCI44393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clatterbuck RE, Eberhart CG, Crain BJ, Rigamonti D. Ultrastructural and immunocytochemical evidence that an incompetent blood-brain barrier is related to the pathophysiology of cavernous malformations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:188–192. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidalgo M, Fraile M, Pires A, Force T, Pombo C, Zalvide J. CCM3/PDCD10 stabilizes GCKIII proteins to promote Golgi assembly and cell orientation. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1274–1284. doi: 10.1242/jcs.061341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher KE, Sacharidou A, Stratman AN, Mayo AM, Fisher SB, Mahan RD, Davis MJ, Davis GE. MT1-MMP- and Cdc42-dependent signaling co-regulate cell invasion and tunnel formation in 3D collagen matrices. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:4558–4569. doi: 10.1242/jcs.050724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais L, Casanova J. In vivo coupling of cell elongation and lumen formation in a single cell. Curr Biol. 2010;20:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais L, Lebreton G, Casanova J. The making of a fusion branch in the Drosophila trachea. Dev Biol. 2012;362:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghabrial AS, Krasnow MA. Social interactions among epithelial cells during tracheal branching morphogenesis. Nature. 2006;441:746–749. doi: 10.1038/nature04829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghabrial AS, Levi BP, Krasnow MA. A systematic screen for tube morphogenesis and branching genes in the Drosophila tracheal system. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golby JA, Tolar LA, Pallanck L. Partitioning of N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion (NSF) protein function in Drosophila melanogaster: dNSF1 is required in the nervous system, and dNSF2 is required in mesoderm. Genetics. 2001;158:265–278. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guclu B, Ozturk AK, Pricola KL, Bilguvar K, Shin D, O’Roak BJ, Gunel M. Mutations in apoptosis-related gene, PDCD10, cause cerebral cavernous malformation 3. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:1008–1013. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000180811.56157.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haasdijk RA, Cheng C, Maat-Kievit AJ, Duckers HJ. Cerebral cavernous malformations: from molecular pathogenesis to genetic counselling and clinical management. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Zhang H, Yu L, Gunel M, Boggon TJ, Chen H, Min W. Stabilization of VEGFR2 signaling by cerebral cavernous malformation 3 is critical for vascular development. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra26. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herwig L, Blum Y, Krudewig A, Ellertsdottir E, Lenard A, Belting HG, Affolter M. Distinct cellular mechanisms of blood vessel fusion in the zebrafish embryo. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1942–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Zhou W, Dong W, Watson AM, Hong Y. Directed, efficient, and versatile modifications of the Drosophila genome by genomic engineering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8284–8289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900641106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SC, Formstecher E, Fehon RG. Sip1, the Drosophila orthologue of EBP50/NHERF1, functions with the sterile 20 family kinase Slik to regulate Moesin activity. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1099–1107. doi: 10.1242/jcs.059469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeya T, Hayashi S. Interplay of Notch and FGF signaling restricts cell fate and MAPK activation in the Drosophila trachea. Development. 1999;126:4455–4463. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AM, Walker C, Westerfield M. mosaic eyes: a zebrafish gene required in pigmented epithelium for apical localization of retinal cell division and lamination. Development. 2001;128:95–105. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AM, Westerfield M. Zebrafish mosaic eyes is a novel FERM protein required for retinal lamination and retinal pigmented epithelial tight junction formation. Curr Biol. 2004;14:711–717. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennison JA, Tamkun JW. Dosage-dependent modifiers of polycomb and antennapedia mutations in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:8136–8140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleaveland B, Zheng X, Liu JJ, Blum Y, Tung JJ, Zou Z, Chen M, Guo L, Lu MM, Zhou D, et al. Regulation of cardiovascular development and integrity by the heart of glass-cerebral cavernous malformation protein pathway. Nat Med. 2009;15:169–176. doi: 10.1038/nm.1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh W, Sachidanandam K, Stratman AN, Sacharidou A, Mayo AM, Murphy EA, Cheresh DA, Davis GE. Formation of endothelial lumens requires a coordinated PKCepsilon-, Src-, Pak- and Raf-kinase-dependent signaling cascade downstream of Cdc42 activation. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1812–1822. doi: 10.1242/jcs.045799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Kolodziej PA. The plakin Short Stop and the RhoA GTPase are required for E-cadherin-dependent apical surface remodeling during tracheal tube fusion. Development. 2002;129:1509–1520. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.6.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ST, Choi KW, Yeo HT, Kim JW, Ki CS, Cho YD. Identification of an Arg35X mutation in the PDCD10 gene in a patient with cerebral and multiple spinal cavernous malformations. J Neurol Sci. 2008;267:177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) for Drosophila neural development. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:251–254. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01791-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llimargas M. The Notch pathway helps to pattern the tips of the Drosophila tracheal branches by selecting cell fates. Development. 1999;126:2355–2364. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubarsky B, Krasnow MA. Tube morphogenesis: making and shaping biological tubes. Cell. 2003;112:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer KE, Jacobs JR. Varicose: a MAGUK required for the maturation and function of Drosophila septate junctions. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagenstecher A, Stahl S, Sure U, Felbor U. A two-hit mechanism causes cerebral cavernous malformations: complete inactivation of CCM1, CCM2 or CCM3 in affected endothelial cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:911–918. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preisinger C, Short B, De Corte V, Bruyneel E, Haas A, Kopajtich R, Gettemans J, Barr FA. YSK1 is activated by the Golgi matrix protein GM130 and plays a role in cell migration through its substrate 14-3-3zeta. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:1009–1020. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200310061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen JP, English K, Tenlen JR, Priess JR. Notch signaling and morphogenesis of single-cell tubes in the C. elegans digestive tract. Dev Cell. 2008;14:559–569. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro C, Neumann M, Affolter M. Genetic control of cell intercalation during tracheal morphogenesis in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2197–2207. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigamonti D, Hadley MN, Drayer BP, Johnson PC, Hoenig-Rigamonti K, Knight JT, Spetzler RF. Cerebral cavernous malformations. Incidence and familial occurrence. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:343–347. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198808113190605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samakovlis C, Hacohen N, Manning G, Sutherland DC, Guillemin K, Krasnow MA. Development of the Drosophila tracheal system occurs by a series of morphologically distinct but genetically coupled branching events. Development. 1996a;122:1395–1407. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samakovlis C, Manning G, Steneberg P, Hacohen N, Cantera R, Krasnow MA. Genetic control of epithelial tube fusion during Drosophila tracheal development. Development. 1996b;122:3531–3536. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal S, Krishnan KS. Lethal comatose mutation in Drosophila reveals possible role for NSF in neurogenesis. Neuroreport. 2001;12:1363–1366. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200105250-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schottenfeld-Roames J, Ghabrial AS. Whacked and Rab35 polarize dynein-motor-complex-dependent seamless tube growth. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:386–393. doi: 10.1038/ncb2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone CE, Hall DH, Sundaram MV. Lipocalin signaling controls unicellular tube development in the Caenorhabditis elegans excretory system. Dev Biol. 2009;329:201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland D, Samakovlis C, Krasnow MA. branchless encodes a Drosophila FGF homolog that controls tracheal cell migration and the pattern of branching. Cell. 1996;87:1091–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81803-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiklova K, Senti KA, Wang S, Graslund A, Samakovlis C. Epithelial septate junction assembly relies on melanotransferrin iron binding and endocytosis in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:1071–1077. doi: 10.1038/ncb2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsarouhas V, Senti KA, Jayaram SA, Tiklova K, Hemphala J, Adler J, Samakovlis C. Sequential pulses of apical epithelial secretion and endocytosis drive airway maturation in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2007;13:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uv A, Cantera R, Samakovlis C. Drosophila tracheal morphogenesis: intricate cellular solutions to basic plumbing problems. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:301–309. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss K, Stahl S, Hogan BM, Reinders J, Schleider E, Schulte-Merker S, Felbor U. Functional analyses of human and zebrafish 18-amino acid in-frame deletion pave the way for domain mapping of the cerebral cavernous malformation 3 protein. Hum Mutat. 2009 doi: 10.1002/humu.20996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Jayaram SA, Hemphala J, Senti KA, Tsarouhas V, Jin H, Samakovlis C. Septate-junction-dependent luminal deposition of chitin deacetylases restricts tube elongation in the Drosophila trachea. Curr Biol. 2006;16:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu VM, Yu MH, Paik R, Banerjee S, Liang Z, Paul SM, Bhat MA, Beitel GJ. Drosophila Varicose, a member of a new subgroup of basolateral MAGUKs, is required for septate junctions and tracheal morphogenesis. Development. 2007;134:999–1009. doi: 10.1242/dev.02785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Smith EC, Whiteheart SW. Requirements for the catalytic cycle of the N-ethylmaleimide-Sensitive Factor (NSF) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1823:159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Xu C, Di Lorenzo A, Kleaveland B, Zou Z, Seiler C, Chen M, Cheng L, Xiao J, He J, et al. CCM3 signaling through sterile 20-like kinases plays an essential role during zebrafish cardiovascular development and cerebral cavernous malformations. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2795–804. doi: 10.1172/JCI39679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.