Abstract

Background

Interventions that improve muscle function may slow decline in physical function and disability in later life. Recent evidence suggests that inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system may maintain muscle function. We evaluated the effect of aldosterone blockade on physical performance in functionally impaired older people without heart failure.

Methods

In this parallel-group, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, community-dwelling participants aged ≥65 years with self-reported problems with activities of daily living were randomized to receive 25 mg spironolactone or identical placebo daily for 20 weeks. The primary outcome was change in 6-minute walking distance over 20 weeks. Secondary outcomes were changes in Timed Up and Go test, Incremental Shuttle Walk Test, Functional Limitation Profile, EuroQol EQ-5D, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale over 20 weeks.

Results

Participants’ mean (standard deviation) age was 75 (6) years. Of the 93% of participants (112/120) who completed the study, 106 remained on medication at 20 weeks. There was no significant difference in change in 6-minute walking distance at 20 weeks between the spironolactone and placebo groups (mean change, −3.2 m; 95% confidence interval, −28.9 to 22.5; P = .81). Quality of life improved significantly at 20 weeks, with an increase in EuroQol EQ-5D score of 0.10 (95% confidence interval, 0.03-0.18; P < .01) in the spironolactone group relative to the placebo group. There were no significant differences in between-group change for other secondary outcomes.

Conclusions

Spironolactone was well tolerated but did not improve physical function in older people without heart failure. Quality of life improved significantly, and the possible mechanisms for this require further study.

Keywords: Angiotensin-converting enzyme, Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, Spironolactone

SEE RELATED EDITORIAL p. 559

Decline in physical function with age is a major public health issue because it is strongly associated with disability in later life.1 Recent evidence from observational studies suggests that inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system may improve muscle function in older people.2 Subsequent randomized controlled trials with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors have shown mixed results. The use of the ACE inhibitor perindopril improved walking distance in functionally impaired older people without heart failure.3 However, in another study in older patients with a high cardiovascular risk profile, ACE inhibitors did not improve muscle strength or physical performance after 6 months.4 Elevated levels of angiotensin II or aldosterone are associated with increased skeletal muscle wasting and decline in skeletal muscle function.5 ACE inhibitors block local aldosterone release temporarily,6 so blocking aldosterone receptors with spironolactone may be a more effective aldosterone-related target to counter the effects of physical impairment with age. Spironolactone could improve skeletal muscle function by increasing the skeletal muscle magnesium content and increasing the levels of Na+/K+ pumps required for muscle contractility,7,8 reducing the proinflammatory cytokine response associated with aging muscle,9,10 and improving vascular endothelial function and skeletal muscle in people without heart failure.11,12

Clinical Significance.

-

•

Interventions that improve muscle function, such as inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, may slow decline in physical function and reduce disability in older adults.

-

•

In this prospective randomized trial, spironolactone did not improve physical function in older adults without heart failure.

-

•

The possibility that spironolactone may have favorable effects on quality of life requires further study.

We therefore designed a clinical trial to examine whether spironolactone could improve physical performance in functionally impaired older people without heart failure.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This was a prospective, parallel-group, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. The study was conducted from November 2008 to April 2011. Patients were recruited from Primary Care using the East of Scotland Node of the Scottish Primary Care Research Network and from Medicine for the Elderly clinical services in NHS Tayside, Scotland. All participants provided written informed consent. Research ethics approval was granted by the Tayside Committee on Medical Research Ethics (REC08/S1402/34), and the study conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients aged ≥65 years with self-reported problems with activities of daily living were eligible. Daily living abilities were not objectively scored. Patients were excluded if they had a clinical diagnosis of heart failure (according to European Society of Cardiology guidelines), left ventricular systolic dysfunction, systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg, serum potassium >5.0 mmol/L, serum sodium <130 mmol/L, serum creatinine >200 μmol/L, estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL, Addison’s disease, or Mini-Mental-State Examination score <20/30. Patients were excluded if they were wheelchair bound, a resident in institutional care, or already taking an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker.

At the baseline screening visit, participants underwent a full clinical examination and an echocardiogram was performed to assess left ventricular systolic function using the SonoSite TITAN ultrasound system (SonoSite Inc, Bothell, Wash). A subjective assessment was made of left ventricular systolic function. This has good reproducibility compared with other methods of echocardiography, such as contrast ventriculography.13 Echocardiography was repeated at 20 weeks to rule out the development of occult left ventricular systolic dysfunction during the study period.

Randomization

Randomization of medication was performed by Tayside Pharmaceuticals (Dundee, UK) using a computer-generated, random-number table to conceal treatment allocation. Medication bottles were labeled with sequential participant numbers. Randomization codes were held by Tayside Pharmaceuticals. The researcher who enrolled the participants and distributed the medication had no access to randomization code. Participants were randomized to receive spironolactone or placebo for 20 weeks. The starting dose was 12.5 mg of spironolactone or placebo and was increased after 2 weeks to reach a maximum dose of 25 mg of spironolactone or placebo.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was change in 6-minute walking distance over 20 weeks. The 6-minute walk test is a measure of submaximal exercise performance and has been validated as a safe, reliable, and repeatable measure of functional status and endurance performance in elderly people.14 The test was performed over a 25-m course using their usual walking aids if required. Standardized encouragement was given at regular intervals. The 6-minute walk test was performed at baseline and 10 and 20 weeks. Secondary outcomes were changes in physical function, self-reported function, mood, and quality of life over 20 weeks. The Incremental Shuttle Walk Test is a safe, reliable, and standardized exercise test of functional capacity in older people.15,16 Participants walked over a 10-m course, and walking speed was externally controlled by beeping signals from an audio cassette. The Timed Up and Go test measures the time taken to rise from a chair, walk 3 m, and return to sit in the chair. The test has been widely used in measuring clinically significant changes in mobility in older frail people and tests explosive muscle power rather than endurance.17,18

The EuroQol questionnaire measures self-reported health-related quality of life and is divided into 2 parts. The EQ-5D contains questions covering 5 domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. The responses are converted to an overall score from −0.59 to 1 using a table of weighted values. The EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS) is a 20-cm visual analogue scale that allows patients to score their overall health state for that day from 0 (worst) to 100 (best). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) measures change in psychologic state. It is a validated tool in older people with chronic illness that minimizes reliance on somatic symptoms when evaluating depression and anxiety.19 The Functional Limitation Profile, a modified version of the Sickness Impact Profile, is a valid self-report measure of physical, psychologic, and social function.20 The test has been successfully used to measure the effect of interventions in older people.21 Secondary outcomes were measured at 10 and 20 weeks.

Other Measurements

Blood samples were obtained to measure serum creatinine, magnesium, urea, and electrolyte levels at baseline and 2, 5, 10, and 20 weeks. Samples were analyzed in the Department of Biochemical Medicine, Ninewells Hospital, using the Roche Modular Analytics system (Roche Diagnostics, Lewes, East Sussex, UK). Plasma aldosterone and B-type natriuretic peptide were measured at baseline and 20 weeks by the Department of Clinical Pharmacology, University of Dundee, using radioimmunoassays with intra-assay coefficient of variation of 13.2% and 5.5%, respectively. Postural blood pressure was measured at baseline and 10 and 20 weeks.

Statistical Analysis

From previous studies in similar populations, we anticipated the mean (standard deviation) 6-minute walking distance to be 300 m with a standard deviation of 50 m.3 We estimated that a final sample size of 88 participants (44 per group) would have 80% power (α = 0.05, 2-tailed) to detect a 30-m difference in walking distance at 20 weeks.22 In anticipation of a dropout rate of 27%, as seen in our previous study, a projected sample size of 120 participants was required to yield 88 completing participants over 20 weeks.

All data entry, data management, and main outcome analyses were performed independently by the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics, University of Glasgow. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Analyses were performed only after all data were entered and the database had been locked. Analyses of the outcomes were performed before breaking the treatment codes. Exploratory subgroup analyses were performed by the investigators using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill) after treatment codes were broken. Differences between groups at baseline were compared using the Student t test.

By using intention-to-treat analysis, differences between treatment groups for the outcomes were assessed by Student t test. Analysis of covariance models were used to compare the change in outcomes across the treatment groups at 10 and 20 weeks. To compensate for effect of regression to the mean, we analyzed the change in outcomes using analysis of covariance models and baseline measurements of physical function and age as covariates. As a safeguard against the influence of any data missing at random, analysis of the primary outcome also was performed using multiple imputation (10 iterations) to replace missing data.

Results

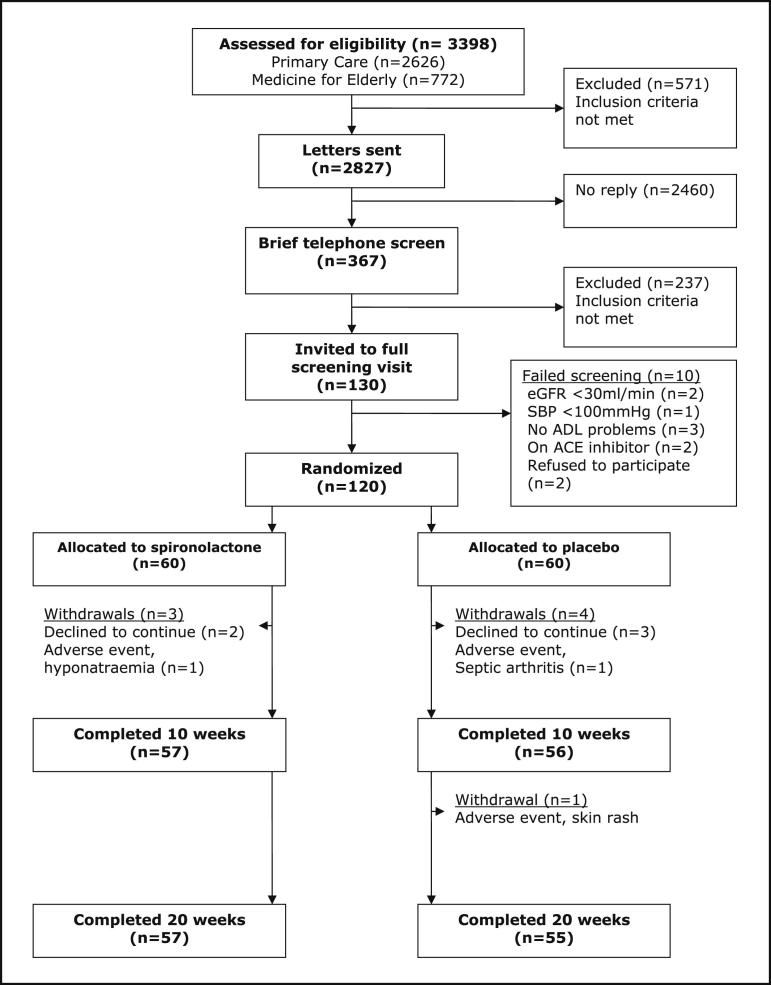

A total of 3398 participants were assessed for eligibility by screening their medical case notes. Of these, 571 (17%) were found to be ineligible. The remaining 2827 were contacted by letter, and 87% (2460/2827) failed to reply. The 367 subjects who replied were briefly screened by telephone; of these, 120 were randomized and 112 of 120 (93%) completed the study. Figure 1 shows patient flow through the study and reasons for withdrawal. No participant had developed left ventricular systolic dysfunction at 20 weeks.

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the study. ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ADL = activities of daily living; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

The median (range) compliance of medication derived from tablet counting was 99% (44%-121%) in the spironolactone group and 99% (51%-110%) in the placebo group. A total of 89% and 94% of participants had compliance >85% in the spironolactone and placebo groups, respectively.

All participants were of white European origin. Groups were well matched at baseline (Table 1) except that participants in the spironolactone group had lower mean serum aldosterone levels and a higher proportion of participants with Parkinson’s disease compared with the placebo group.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Spironolactone (n = 60) | Placebo (n = 60) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (y) (SD) | 75.1 (5.6) | 74.2 (6.5) | .43 |

| Male sex | 31 (52.5%) | 34 (56.7%) | .65 |

| Weight (kg) | 78.2 (14.0) | 77.0 (18.7) | .69 |

| Height (cm) | 168 (7) | 165 (10) | .15 |

| MMSE (median, IQR) | 29 (2) | 29 (2) | .67 |

| Walking aid | |||

| None | 37 (63%) | 46 (77%) | .10 |

| 1 stick | 17 (29%) | 11 (18%) | .18 |

| 2 sticks | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | .18 |

| Zimmer frame | 2 (3%) | 0 | .15 |

| Triwheel walker | 1 (2%) | 2 (3%) | .57 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 19 (32%) | 16 (27%) | .50 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 8 (14%) | 7 (12%) | .76 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 3 (5%) | 2 (3%) | .63 |

| Myocardial infarction | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | .55 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (9%) | 7 (12%) | .56 |

| COPD | 10 (17%) | 13 (22%) | .52 |

| Stroke/TIA | 5 (9%) | 4 (7%) | .71 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 6 (10%) | 1 (2%) | .05 |

| Osteoarthritis | 24 (41%) | 30 (50%) | .31 |

| Medication | |||

| Loop diuretics | 3 (5%) | 3 (5%) | 1.00 |

| Thiazide diuretics | 8 (13%) | 11 (18%) | .43 |

| Aspirin | 17 (29%) | 18 (30%) | .71 |

| Statins | 15 (25%) | 9 (15%) | .17 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 10 (17%) | 6 (10%) | .30 |

| Beta-blockers | 3 (5%) | 5 (8%) | .53 |

| Bronchodilators | 3 (5%) | 5 (8%) | .53 |

| Inhaled steroids | 4 (3%) | 4 (3%) | 1.00 |

| Total no. of medications (median, IQR) | 5 (3) | 5 (3) | .97 |

BP = blood pressure; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IQR = interquartile range; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; SD = standard deviation; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

Note: Except where mentioned, values are mean and SD.

Primary Outcome

The mean 6-minute walking distance in the spironolactone group increased by 30.5 m (9.1%) compared with 33.7 m (9.8%) in the placebo group at 20 weeks. Unadjusted comparison of the change in 6-minute walking distance between baseline and follow-up showed no significant improvement in the treatment group compared with placebo at 20 weeks with a between group difference of −3.2 m (95% confidence interval [CI], −28.9 to 22.5; P = .81). There was no significant difference between the groups in distance walked at 10 weeks (Table 2). Adjusted analyses also show no significant change in 6-minute walking distance between baseline and 20 weeks (Table 3).

Table 2.

Unadjusted Changes in Outcome Measures from Baseline

| Outcome Measure | Time | Spironolactone | Placebo | Difference Between Groups (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-min walking distance (m) | 10 wk | 27.4 | 27.5 | −0.1 (−22.9 to 22.7) | .99 |

| 20 wk | 30.5 | 33.7 | −3.2 (−28.9 to 22.5) | .81 | |

| Timed Up and Go test (s) | 10 wk | −1.4 | −1.2 | −0.2 (−1.3 to 0.9) | .72 |

| 20 wk | −1.3 | −1.3 | 0.04 (−1.3 to 1.3) | .95 | |

| ISWT distance (m) | 10 wk | 13.9 | 17.6 | −3.7 (−21.4 to 27.5) | .72 |

| 20 wk | 25.4 | 22.4 | 3.1 (−21.4 to 27.5) | .81 | |

| FLP total score | 10 wk | −16 | −17 | 1 (−45 to 47) | .97 |

| 20 wk | −14 | −22 | 8 (−49 to 64) | .78 | |

| EuroQol EQ-5D | 10 wk | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04 (−0.03 to 0.11) | .22 |

| 20 wk | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.10 (0.03-0.18) | .006 | |

| EuroQol EQ-VAS | 10 wk | 4.2 | 2.8 | 1.5 (−4.3 to 7.2) | .62 |

| 20 wk | −0.3 | 1.6 | −1.9 (−8.3 to 4.5) | .55 | |

| HADS-D score | 10 wk | −1.11 | −0.25 | −0.84 (−1.58 to −0.09) | .03 |

| 20 wk | −0.23 | −0.04 | −0.20 (−0.97 to 0.58) | .62 | |

| HADS-A score | 10 wk | −0.11 | −0.23 | 0.12 (−0.83 to 1.09) | .80 |

| 20 wk | 0.33 | −0.45 | 0.78 (−0.17 to 1.69) | .11 |

EQ-VAS = EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ISWT = Incremental Shuttle Walk Test; FLP = Functional Limitation Profile.

Table 3.

Change in 6-Minute Walking Distance from Baseline to 20 Weeks, Using Models for Adjustment

| Between Group Difference (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted for baseline 6-min walking distance (m) | −3.2 (−28.9 to 22.5) | .81 |

| Adjusted for baseline 6-min walking distance (m) | −4.7 (−29.9 to 20.5) | .71 |

| Adjusted for baseline 6-min walking distance (m) and age (y) | −3.7 (−28.6 to 21.2) | .77 |

| Multiple imputation adjusted for baseline 6-min walking distance (m) | −5.0 (−28.5 to 18.5) | .67 |

| Multiple imputation adjusted for baseline 6-min walking distance (m) and age (y) | −6.1 (−29.7 to 17.6) | .62 |

CI = confidence interval.

Secondary Outcome Measures

The changes in secondary measures from baseline are shown in Table 2. Secondary measures of muscle function and physical function (Timed Up and Go test, Incremental Shuttle Walk Test, and Functional Limitation Profile) showed no improvement with spironolactone compared with placebo at follow-up. There was a significant difference in the EQ-5D utility score of 0.10 (95% CI, 0.03-0.18) in the spironolactone group compared with the placebo group at 20 weeks (P < .01). This comparison remained significant even after adjustment for baseline EQ-5D utility score and age as covariates (0.07; 95% CI, 0-0.13; P = .04). Post hoc subgroup analysis showed a significant improvement in pain (P < .01) within the EQ-5D score domains, with joint pain due to osteoarthritis reported as the main cause of pain.

There was a significant decline in the unadjusted HADS-D score of 0.84 in the spironolactone group compared with the placebo group at 10 weeks (P = .03), that is, an improvement in mood. However, this difference did not persist at 20 weeks, and adjustment for baseline HADS score rendered the between-group difference in change at 10 weeks nonsignificant: −0.57 (95% CI, −1.27 to 0.12; P = .11).

Other Measures

There was a significant decline in systolic (7 mm Hg, P = .02) and diastolic (5 mm Hg, P = .03) blood pressures in the spironolactone group at 10 weeks compared with the placebo group. Nonsignificant changes were seen in both systolic (6 mm Hg, P = .06) and diastolic (3 mm Hg, P = .10) blood pressures at 20 weeks. There was no significant decline in postural blood pressure with spironolactone compared with placebo at 20 weeks.

Changes in blood test results are summarized in Table 4. As expected, spironolactone was associated with a significant increase in serum potassium, serum creatinine, and serum aldosterone, with spironolactone at 20 weeks in keeping with aldosterone blockade.

Table 4.

Changes in Blood Test Results at 20 Weeks from Baseline

| Test | Spironolactone (95% CI) | Placebo (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum potassium (mmol/L) | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.1) | .01 |

| Serum sodium (mmol/L) | −0.9 (−1.6 to −0.3) | −0.6 (−1.2 to 0.1) | .43 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 0.5 (0.2-0.9) | 0.4 (0.0-0.8) | .67 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 6.7 (6.1-9.4) | 2.5 (−0.2 to 5.2) | .03 |

| Serum magnesium (mmol/L) | −0.02 (−0.03 to 0.01) | −0.02 (−0.03 to 0.00) | .55 |

| Aldosterone (pg/mL) | 136.9 (101.3-172.7) | 20.1 (−15.9 to 56.2) | .001 |

| B-type natriuretic peptide (pg/mL) | −4.2 (−11.6 to 3.3) | −1.2 (−8.6 to 6.4) | .57 |

CI = confidence interval.

Adverse Events

Adverse events that led to withdrawal of participants are shown in Figure 1. Of the participants taking spironolactone, 2 developed a rash and 1 had gynecomastia. Medication was discontinued in 4 patients in the spironolactone group (serum sodium <130 mmol/L in 2, decrease in systolic blood pressure to <100 mm Hg in 1, skin rash in 1) and 2 patients in the placebo group (skin rash in 1 and persistent dizziness in 1). Five participants (2 in the spironolactone group and 3 in the placebo group) were unable to tolerate up-titration of dose at 2 weeks because of an increase in serum potassium (>5.0 mmol/L but <5.5 mmol/L). All 5 remained on 12.5 mg of spironolactone/placebo for the duration of the study without any adverse effect. No participant in either group developed a potassium level >5.5 mmol/L.

Discussion

This study found that spironolactone did not improve physical performance, as measured by change in 6-minute walk test at 20 weeks, compared with placebo. The minimum clinically important difference of 30 m falls outside the 95% CIs around our results, making it highly unlikely that we have missed a clinically important improvement in the 6-minute walk distance. The minimum clinically important difference in 6-minute walking distance in older people without heart failure may be as low as 20 m.22 Even this more conservative value falls outside the 95% CIs derived from the imputed data set. The lack of change in the Timed Up and Go test, Incremental Shuttle Walk Test, and Functional Limitation Profile (a self-reported measure of physical function) with spironolactone reinforces our neutral finding with the primary outcome. The final sample size exceeded the required target sample size because of a lower than expected dropout rate, which was sufficient to detect a clinical effect in the primary outcome. Our results were consistent with the Randomized Aldosterone Antagonism in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction trial, in which no significant improvement was seen in 6-minute walk distance with aldosterone antagonist eplenerone in patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction.23

Spironolactone significantly improved quality of life with a between-group difference of 0.10 in the EQ-5D compared with placebo, a value that exceeds the minimally clinically important difference of 0.08.24 However, because this was a secondary end point, this observation must be interpreted with caution. The improvement in the EQ-5D score in the spironolactone group was not matched by a similar improvement in the EQ-VAS. This is in keeping with findings from other studies that found that EQ-VAS is less sensitive to change than EQ-5D.25

A major strength of this study was that the effect of aldosterone antagonism was tested in the absence of ACE inhibition. Spironolactone may indeed have a role in improving physical performance, but most of the supporting evidence for this comes from studies in animals or in patients with chronic heart failure, where improvements in physical performance could be attributed to improvements in cardiac function by reducing myocyte apoptosis and improving left ventricular ejection fraction.26 Previous work showed that ACE inhibitors improve exercise performance in older people both with and without chronic heart failure.3,27 However, ACE inhibitors did not improve physical performance in patients with cardiovascular risk factors.4 It is possible that targeting other components of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (eg, angiotensin II) may improve muscle function. There also is a lack of evidence to suggest whether improvement in physical performance can be sustained long-term with ACE inhibition. Observational studies show that aldosterone levels eventually return to baseline with long-term ACE inhibition.26 Therefore, it could be hypothesized that aldosterone antagonism may be beneficial to physical performance in the longer term when used in conjunction with ACE inhibition. However, this theory would require further research.

Despite the lack of effect on physical performance, there was a significant improvement in health-related quality of life in the spironolactone group. However, these findings must be interpreted with caution, and further trials using health-related quality of life as the primary end point are required to confirm this observation. Other work with spironolactone has shown improvement in quality of life in association with improvement in physical performance or cardiac symptoms in patients with chronic heart failure.26,28 A similar improvement in quality of life, as measured by improvement in EQ-5D score, was seen in our previous study with ACE inhibitors in older people without heart failure.3 This suggests a potential common mechanism involving inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and improvements in health-related quality of life; however, further research is required to further explore this hypothesis.

Improvements in health-related quality of life may have occurred because of other pharmacologic effects of spironolactone. Post hoc analysis showed a significant improvement in the pain domain of the EQ-5D score. Joint pain from osteoarthritis was the most common cause of pain. No previous studies have reported a reduction in pain with spironolactone. However, it is feasible that spironolactone may have anti-inflammatory effects. Aldosterone is proinflammatory, making it likely that by blocking aldosterone spironolactone may beneficially affect inflammation and pain.29 Spironolactone also increases plasma cortisol, a potentially anti-inflammatory substance.30 Finally, in patients with chronic arthritis, spironolactone markedly suppressed the transcription of several proinflammatory cytokines, including the release of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1, and interleukin-6.10 Our observation suggests possible wider pharmacologic benefits of spironolactone in functionally impaired older people and merits further research.

Study Limitations

First, the use of self-reported problems in activities of daily living may have introduced subject bias. The use of physical performance tests, such as the Sit to Stand test or the short physical performance battery test, may have provided a more objective method to measure participants’ functional state. Second, although changes in serum potassium, creatinine, and aldosterone were consistent with known physiologic effects of aldosterone blockade.28 It is possible that a higher dose of spironolactone may be required to influence the pathophysiologic effects of aging on skeletal muscle to a degree that improves physical performance. The low rate of adverse events with 25 mg of spironolactone provides encouragement for the potential use of a higher dose of spironolactone in similar older populations. Third, it is possible that a treatment duration of greater than 20 weeks is required to elicit changes in physical function. In the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study trial, the pharmacologic effects of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure was shown over a follow-up period of 24 months.28 Finally, the mean baseline 6-minute walk distance was higher than in previous studies involving frail older people.3 Therefore, our study population may not have been the subgroup most likely to benefit.

Conclusions

Interventions that improve muscle function, such as inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, may slow decline in physical function and reduce disability in older people. In this prospective randomized controlled trial, spironolactone did not improve physical performance in functionally impaired older people without heart failure, despite being well tolerated with few side effects. The possibility that spironolactone may have favorable effects on quality of life requires further research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the study participants for their cooperation; the staff at the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics, University of Glasgow, Scotland, for their role in data management and statistical analysis; and the staff at the East Node of the Scottish Primary Care Research Network, for their help with participant recruitment.

Michael W. Rich, MD, Section Editor

Footnotes

Funding: This study was funded by the Chief Scientists Office, Scottish Executive Department of Health, Scottish Government (Grant CZB/4/635). The University of Dundee was the study sponsor. Neither the University of Dundee nor the Chief Scientists Office had a role in the study design; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or the writing of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: None.

Authorship: All authors had access to the data and played a role in writing this manuscript. Clinical Trial Registration number: International Standard Randomization Controlled Trial Register no. ISRCTN03869290.

References

- 1.Rantanen T., Guralnik J.M., Sakari-Rantala R. Disability, physical activity, and muscle strength in older women: the Women’s Health and Aging Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:130–135. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onder G., Penninx B.W., Balkrishnan R. Relation between use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and muscle strength and physical function in older women: an observational study. Lancet. 2002;359:926–930. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sumukadas D., Witham M.D., Struthers A.D., McMurdo M.E. Effect of perindopril on physical function in elderly people with functional impairment: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2007;177:867–874. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cesari M., Pedone C., Incalzi R.A., Pahor M. ACE-inhibition and physical function: results from the Trial of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibition and Novel Cardiovascular Risk Factors (TRAIN) study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burniston J.G., Saini A., Tan L.B., Goldspink D.F. Aldosterone induces myocyte apoptosis in the heart and skeletal muscles of rats in vivo. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:395–399. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cicoira M., Zanolla L., Franceschini L. Relation of aldosterone “escape” despite angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor administration to impaired exercise capacity in chronic congestive heart failure secondary to ischemic or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:403–407. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyckner T., Wester P.O., Widman L. Effects of spironolactone on serum and muscle electrolytes in patients on long-term diuretic therapy for congestive heart failure and/or arterial hypertension. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1986;30:535–540. doi: 10.1007/BF00542411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aagaard N.K., Andersen H., Vilstrup H. Muscle strength, Na, K-pumps, magnesium and potassium in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis–relation to spironolactone. J Intern Med. 2002;252:56–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francis J., Beltz T., Johnson A.K., Felder R.B. Mineralocorticoids act centrally to regulate blood-borne tumor necrosis factor-alpha in normal rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R1402–R1409. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00027.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bendtzen K., Hansen P.R., Rieneck K. Spironolactone inhibits production of proinflammatory cytokines, including tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma, and has potential in the treatment of arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;134:151–158. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clement D.L. Effect of spironolactone on systemic blood pressure, limb blood flow and response to sympathetic stimulation in hypertensive patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1982;21:263–267. doi: 10.1007/BF00637611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farquharson C.A., Struthers A.D. Aldosterone induces acute endothelial dysfunction in vivo in humans: evidence for an aldosterone-induced vasculopathy. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002;103:425–431. doi: 10.1042/cs1030425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen-Urstad K., Bouvier F., Hojer J. Comparison of different echocardiographic methods with radionuclide imaging for measuring left ventricular ejection fraction during acute myocardial infarction treated by thrombolytic therapy. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:538–544. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00964-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enright P.L., McBurnie M.A., Bittner V. The 6-min walk test: a quick measure of functional status in elderly adults. Chest. 2003;123:387–398. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh S.J., Morgan M.D., Scott S. Development of a shuttle walking test of disability in patients with chronic airways obstruction. Thorax. 1992;47:1019–1024. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.12.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dyer C.A., Singh S.J., Stockley R.A. The incremental shuttle walking test in elderly people with chronic airflow limitation. Thorax. 2002;57:34–38. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shumway-Cook A., Brauer S., Woollacott M. Predicting the probability for falls in community-dwelling older adults using the Timed Up & Go Test. Phys Ther. 2000;80:896–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Podsiadlo D., Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zigmond A.S., Snaith R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollard B., Johnston M. Problems with the sickness impact profile: a theoretically based analysis and a proposal for a new method of implementation and scoring. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:921–934. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witham M.D., Gray J.M., Argo I.S. Effect of a seated exercise program to improve physical function and health status in frail patients > or = 70 years of age with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:1120–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perera S., Mody S.H., Woodman R.C., Studenski S.A. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:743–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deswal A., Richardson P., Bozkurt B., Mann D.L. Results of the Randomized Aldosterone Antagonism in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction trial (RAAM-PEF) J Card Fail. 2011;17:634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickard A.S., Neary M.P., Cella D. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:70. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurst N.P., Jobanputra P., Hunter M. Validity of Euroqol–a generic health status instrument–in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Economic and Health Outcomes Research Group. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:655–662. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.7.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cicoira M., Zanolla L., Rossi A. Long-term, dose-dependent effects of spironolactone on left ventricular function and exercise tolerance in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:304–310. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01965-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutcheon S.D., Gillespie N.D., Crombie I.K. Perindopril improves six minute walking distance in older patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction: a randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. Heart. 2002;88:373–377. doi: 10.1136/heart.88.4.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pitt B., Zannad F., Remme W.J. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709–717. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocha R., Rudolph A.E., Frierdich G.E. Aldosterone induces a vascular inflammatory phenotype in the rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1802–H1810. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01096.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swaminathan K., Davies J., George J. Spironolactone for poorly controlled hypertension in type 2 diabetes: conflicting effects on blood pressure, endothelial function, glycaemic control and hormonal profiles. Diabetologia. 2008;51:762–768. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-0972-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]