At first glance, implementing evidence-based treatments for ethnically diverse youth may appear to raise some concerns. Do manualized treatments work for the diverse youth we see in our communities? Should clinicians only use culturally-specific treatments? Unfortunately, the literature is not definitive. Several studies have found that tailoring interventions for specific populations can increase their effectiveness1–5 while others have found that cultural adaptations of an intervention may actually dilute the effectiveness of the original treatment even though retention is improved.6 What appears to be important is to strike a balance between fidelity to evidence-based treatment and culturally-informed care.

This paper provides illustrations from a school-community-academic partnership’s dissemination of the Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools7 program to ethnically diverse communities nationwide. CBITS is an evidence-based intervention program initially developed for ethnic minority and immigrant youth exposed to trauma. CBITS was created to decrease the negative effects of trauma exposure in an ethnically and linguistically diverse group of primarily low-income children while being delivered in the real-world setting of schools. 8, 9 In a randomized controlled study, Mexican and Central American youth showed significant reduction in post-traumatic stress and depressive symptoms.10, 11 Similar positive effects have been found in dissemination evaluations of CBITS in other communities12, including urban African American13, Native American14, and rural communities.15 Although our CBITS partnership recommends program evaluations, we recognize that it is not always feasible for each community to do systematic evaluation for each adaptation or modification of CBITS.

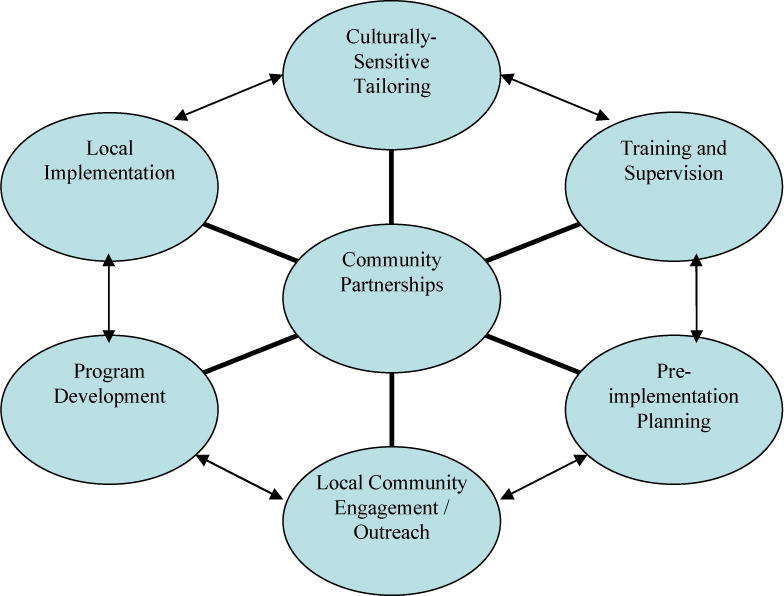

In delivering CBITS, we have confronted common issues that arise when trying to deliver an evidence-based intervention to youth from a broad range of ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds. We present several examples of how we use community partnerships throughout all phases of dissemination, from program development, pre-implementation planning, to delivery of CBITS groups (see Figure 1). Community partnerships refer to collaboration between key stakeholders from the local school and its surrounding community including school personnel, parents, community organizations, faith-based groups, clinicians and researchers. This approach addresses contextual and cultural issues at every stage so that CBITS is tailored for each unique community. We have found this to be a promising model for reaching diverse and underserved populations and increasing community engagement.8, 16

Figure 1.

Model for Using Community Partnerships to Provide Culturally-Sensitive Evidence-Based Treatment

Program Development

To build a sustainable and accessible program, community partnerships with key stakeholders are needed to develop treatment strategies that are consistent with community priorities, culture, and values. During development of CBITS, school partners identified exposure to violence as a key issue for many students with mental health problems and poor academic performance.16 Different aspects of the intervention were then tailored in response to formal (focus groups) and informal feedback from parents and community members. These focus groups highlighted existing engagement strategies, specific cultural, school, and community issues, and potential barriers. For example, in a multicultural school serving both African American and Latino families, racial tensions were identified as a potential barrier. We learned it was crucial to work with existing parent groups and school staff who represented these ethnic groups and were familiar with their communities. The focus groups provided insight into historical racial tensions and informed delivery of CBITS to minimize mistrust and improve communication. As a result, all information about CBITS was presented to both African American and Latino families together, simultaneously translating for monolingual Spanish-speaking parents, instead of presenting information in separate forums, which likely would have raised questions about unequal access to information.

Given the ethnically and culturally heterogeneous environments of many schools in which CBITS has been implemented, school partners have emphasized the importance of the program’s flexibility in addressing trauma for students from a variety of different communities. Thus, the core components of the program are not culture-specific. Instead, a significant portion of consultation and training with clinicians is devoted to discussing the best way to meet the needs of the community being served, emphasizing cultural competence and systems competence in working within the school organization, while maintaining the essential components of cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Pre-implementation Planning

In addition to collaborating with community partners in the development phase of the intervention, CBITS has focused on improving ongoing local community engagement during pre-implementation planning. Multi-stakeholder planning committees have identified optimal methods for local service delivery, including outreach, implementation, training/supervision, and evaluation. This planning phase prior to delivering the program has been essential in tailoring how this program is introduced to a community and in identifying important contextual issues specific to a population. In one faith-based setting serving primarily immigrant Latino families, ongoing planning meetings with parents, providers, community leaders, and lay health workers occurred well before any CBITS groups were implemented at this parochial school. These planning meetings were instrumental in developing ways to introduce the importance of a trauma intervention in this community. Parents decided to share personal testimonies of their own traumatic experiences at a school-wide parent meeting, illustrating from their first-hand accounts the need for such an intervention.

CBITS clinicians have also worked with different types of providers, including case managers, nurses, parents, and lay health promoters who have each attended CBITS trainings and trauma awareness sessions. Thus, everyone who is involved in the CBITS program, from initial engagement and delivery of the intervention to parent outreach, is conversant in trauma-informed practices even if they may not be implementing the treatment. This has led to greater community outreach, buy-in, and support for the program.9

It has also been important for clinicians to be thoughtful about implementing a treatment program within a school context and understanding the dynamics between community members and school staff. School mental health clinicians are encouraged to understand the culture and priorities of their particular school and the school’s interface with families in the community, to increase administrator, teacher, and community support, and to collaborate with school personnel to address logistics and the competing demands on school staff.

Culturally-Sensitive Tailoring and Local Implementation

In the implementation phase of CBITS, local clinicians are encouraged to thread culturally-relevant people, materials, and concepts throughout treatment as well as address language needs, both to increase engagement and clinical salience. As shown in Table 1, TV characters (e.g., “That’s So Raven”), sports or historical figures (e.g., Shaquille O’Neal, Rosa Parks, Cesar Chavez), musicians, and graphic novels can be used to convey examples of treatment concepts such as cognitions and problem-solving. Clinicians have incorporated local customs such as burning “sweet grass” during relaxation exercises with particular Native American groups.

Table 1.

Tailoring CBITS Core Components for Diverse Communities

| Treatment Components | CBITS Implementation Examples |

|---|---|

| Psychoeducation | • Expression of distress Use terminologies that are relevant. For example, with certain Latino groups may refer to “nervios” or “mal ojo” |

| Cognitive Coping | • A child keeping a Yugioh “power card” in his pocket to remind him to use his “hot seat” (coping) thoughts • Describing the link between thoughts and feelings and how to use cognitive restructuring using the example of Shaquille O’Neill entering a basketball game or Raven from “That’s So Raven” making assumptions about what will happen in the future • Showing a Spongebob comic strip where he catastrophizes a situation as dangerous that really is not. |

| Relaxation | • Burning “sweet grass” during relaxation exercises with particular Native American groups |

| Social Problem-Solving | • Blending in aspects of spiritual coping (i.e., prayer, meditation, talking to a religious leader, seeking forgiveness, rituals) as potential actions to take in faith-based schools and with diverse groups of students where this is an important part of their culture/context. • Incorporating the language the students use during brainstorming activity (i.e, “Call her out”, “ Get in his face”) |

| Trauma Narrative | • Writing a song or rap about the traumatic event • Creating a poem or graphic novel to help process part of their trauma narrative in a way that feels both developmentally and culturally-sensitive. |

Previous research has described important cultural issues to integrate into any treatment, such as help-seeking preferences, expressions of distress, communication styles, migration experiences, family values, and sociopolitical history.1, 4, 17, 18 These concepts are often central to understanding the experience of specific populations, and we encourage these issues to be addressed throughout planning and implementation. Collaborations with cultural liaisons, who have cultural knowledge and clinical expertise, is critical to implementing interventions in ways that are congruent with and respectful of the cultural issues specific to communities.

As an example, at one school with a large percentage of recent Latino immigrants, school and community members were aware that a number of students had experienced traumas related to their crossing of the U.S.-Mexico border. In response to these concerns, sessions related to psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, and problem-solving were modified to be sensitive to migration traumas. For example, coping strategies were developed to address traumatic reminders when students traveled back across the border to their native country for visits. During the psychoeducation session, group leaders at this school also discussed various expressions of distress, including somatization, to help students understand that there are different ways of expressing psychological pain and help them to identify their own experience. For parents, additional parent sessions were added to the existing psychoeducation module to address parenting issues, immigration, and acculturative stress.

Throughout the CBITS consultation, training, and supervision, there is an emphasis on the need for each clinician to implement CBITS in a way that applies cultural and contextual knowledge of the student population to effectively convey core treatment concepts. As clinicians are taught the key components of this evidence-based trauma treatment, an emphasis is placed on the importance of building a relationship with each child by attending to each person’s unique background even though this is a group intervention. For example, there is ongoing discussion of cultural sensitivity, such as not discounting a response as unrealistic if it may be appropriate for the child’s family or cultural beliefs (i.e., belief in ghosts, night walkers). The manual’s individual case conceptualization and treatment plan also assists clinicians in thinking about each child’s individual needs based on endorsed symptoms, functional impairment, and family and cultural context.

Case Example

In a small school on a Native American reservation, a tribal elder offered a blessing for the CBITS training being conducted on the reservation site, as well as at the outset of the actual CBITS groups. Each group consisted of 6 middle school students who came from the same reservation community and knew each other and their family members very well. Because of the clinician’s knowledge of a cultural custom within the tribe to not speak the name of the deceased, part of the training focused on how to problem-solve this issue if it were to come up during the “exposure” exercises (sessions which involve recounting the traumatic event). As the groups began, particular care was made to assess the acculturative status and belief systems of each participant. In one group, all of the students were comfortable saying the name of a deceased person and saw this belief as more “traditional” than their families’ beliefs, so the exposure exercises did not have to be altered. However in another group at this school, there was a boy who did follow this custom, and the group members did imaginal exposures and drawings during those group sessions and respected this custom when they recounted their traumas in group by not speaking the names of anyone who had died.

Conclusion

A community-partnered framework in the development and dissemination of CBITS has been a useful and effective approach to integrating cultural sensitivity and evidence-based practice. Local community partnerships also increase access, engagement, and treatment retention. Although the core components of CBITS remain intact, the way in which it is implemented or “packaged” is always group-specific. Critical discussions about the cultural characteristics of the students and families being served can occur in the planning phase, during training, and throughout supervision. During early phases of the group leader’s efforts to master delivering CBITS to a culturally diverse clientele, supervision is especially critical. Delivering an EBT, even those that have been manualized and are run in a group modality, requires clinicians to remain vigilant about learning from each student and community about how the treatment components can be conveyed in a respectful and relevant way.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the UCLA Training Grants (MH073517:04A1; T32 HS00046), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (1 SM57283), and the National Institute of Mental Health (1K08MH069741:05; P30 MH068639:05). The authors would like to thank Lisa Jaycox and Marleen Wong for their consultation, and Pamela Vona for editorial assistance. This work would not be possible without the collaborative efforts of countless youth, families, and professionals that have contributed to the development and dissemination of CBITS.

References

- 1.Bernal G. Intervention development and cultural adaptation research with diverse families. Fam Process. 2006;45(2):143–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botvin GJ, Baker E, Dusenbury L, Botvin EM, Diaz T. Long-term follow-up results of a randomized drug abuse prevention trial in a white middle-class population. JAMA. 1995;273(14):1106–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirachi TW, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. Effective recruitment for parenting programs within ethnic minority communities. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 1997;14(1):23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szapocznik J, Kurtines WM, Foote FH, Perez-Vidal A, Hervis OE. Conjoint versus one-person family therapy: further evidence for the effectiveness of conducting family therapy through one person with drug-abusing adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54(3):395–397. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossello J, Bernal G. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal treatments for depression in Puerto Rican adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(5):734–745. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R, Tait C, Turner C. Effectiveness of school-based family and children’s skills training for substance abuse prevention among 6-8-year-old rural children. Psychol Addict Behav. 2002;16(4):S65–71. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.16.4s.s65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaycox LH. Cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools. Longmont, CO: Sopris West Educational Services; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein BD, Kataoka S, Jaycox LH, et al. Theoretical basis and program design of a school based mental health intervention for traumatized immigrant children: a collaborative research partnership. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2002;29(3):318–326. doi: 10.1007/BF02287371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kataoka SH, Fuentes S, O’Donoghue VP, et al. A community participatory research partnership: the development of a faith-based intervention for children exposed to violence. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, et al. A school-based mental health program for traumatized Latino immigrant children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(3):311–318. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Kataoka SH, et al. A mental health intervention for schoolchildren exposed to violence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(5):603–611. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langley A, Van Den Brandt J, Stephan S, Green M, Rosen-McGill E, Sullivan K, Pitchford Jennifer, Stolle D, Schuldberg D, van den Pol R, Morsette A, Jaycox L, Wong M. School-Based Mental Health Programs for Children Exposed to Trauma; 23rd International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Annual Meeting; Nov 14-17, 2007; Baltimore, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stephan S, Green M, Rosen-Gill E, Sullivan K, Pitchford J. Implementation and Evaluation of Trauma-informed Intervention in Baltimore City Schools. School-Based Mental Health Programs for Children Exposed to Trauma; 23rd International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Annual Meeting; Nov 14-17, 2007; Baltimore, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stolle D, Schuldberg D, van den Pol R, Morsette A. Trauma Symptom Reduction and Academic Correlates of Violence Exposure Amongst Native American Students. School-Based Mental Health Programs for Children Exposed to Trauma; 23rd International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Annual Meeting; Nov 14-17, 2007; Baltimore, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Den Brandt J. School-Based Trauma Treatment: CBITS in Wisconsin. School-Based Mental Health Programs for Children Exposed to Trauma; 23rd International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies Annual Meeting; Nov 14-17, 2007; Baltimore, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong M. Commentary: building partnerships between schools and academic partners to achieve health related research agenda. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S149–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang W. The psychotherapy adaptation and modification framework: application to Asian Americans. Am Psychologist. 2006;61(7):702–715. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pumariega AJ, Rothe E, Pumariega JB. Mental health of immigrants and refugees. Community Ment Health J. 2005;41(5):581–597. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-6363-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]