Abstract

The architectonic features of the ventroposterior nucleus (VP) were visualized in coronal brain sections from two macaque monkeys, two owl monkeys, two squirrel monkeys, and three galagos that were processed for cytochrome oxidase, Nissl bodies, or the vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (vGluT2). The traditional ventroposterior medial (VPM) and ventroposterior lateral (VPL) subnuclei were easily identified, as well as the forelimb and hindlimb compartments of VPL, as they were separated by poorly staining, cell-poor septa. Septa also separated other cell groups within VPM and VPL, specifically in the medial compartment of VPL representing the hand (hand VPL). In one squirrel monkey and one galago we demonstrated that these five groups of cells represent digits 1–5 in a mediolateral sequence by injecting tracers into the cortical representation of single digits, defined by microelectrode recordings, and relating concentrations of labeled neurons to specific cell groups in hand VPL. The results establish the existence of septa that isolate the representation of the five digits in VPL of primates and demonstrate that the isolated cell groups represent digits 1–5 in a mediolateral sequence. The present results show that the septa are especially prominent in brain sections processed for vGluT2, which is expressed in the synaptic terminals of excitatory neurons in most nuclei of the brainstem and thalamus. As vGluT2 is expressed in the synaptic terminations from dorsal columns and trigeminal brainstem nuclei, the effectiveness of vGluT2 preparations in revealing septa in VP likely reflects a lack of synapses using glutamate in the septa. J. Comp. Neurol. 519:738–758, 2011.

INDEXING TERMS: area 3b, somatosensory maps, digit representation, vGluT2

Primary somatosensory cortex (S1) in mammals represents the contralateral body surface, as well as both the contralateral and ipsilateral oral cavity (Johnson, 1990; Iyengar et al., 2007). The representation is generally topographic, but the skin of the body is not a simple sensory sheet, as it has the protrusions of the limbs and disruptions such as those between the digits, toes, and lips. In addition, given regions of skin are subserved by different classes of cutaneous receptors with different functional properties. All these features have the potential of disrupting the continuity of somatotopic representations in cortex, as well as the thalamus and brainstem (Kaas and Catania, 2002). Perhaps the best-known example is the “barrel field” of S1 in rats and mice where clusters of cells separated by septa are best activated by specific, individual sensory whiskers on the side of the face (Woolsey et al., 1975). A similar pattern of “barreloids” has been identified in the ventroposterior nucleus of the thalamus (Van der Loos, 1976; see Haidarliu and Ahissar, 2001, for review). In addition, using a more sensitive procedure, Dawson and Killackey (1987) revealed separate cortical modules for digits, toes, and pads of the hands and feet. Many more examples can be given, but results from the thalamus and cortex are more relevant to the present study. Most notably, a cell-poor septum, the arcuate lamella, has long been recognized between the representation of the face and hand in the ventroposterior nucleus (e.g., Clark, 1932). A similar septum occurs between the hand and face representations in S1 (area 3b) of monkeys and other primates (see Qi and Kaas, 2004). More recently, myelin-dense, cell-poor septa have been described between the representations of individual digits in area 3b of owl monkeys (Jain et al., 1998) and macaque monkeys (Qi and Kaas, 2004). These septa are apparent early in postnatal development, and they are not altered by sensory loss in adult monkeys. Thus, they can serve as a useful guide to the cortical somatotopy that emerged early in development even after cortical somatotopy has been altered by sensory loss.

In the ventroposterior nucleus, the septum between the representation of the face in the ventroposterior medial subnucleus (VPM) and the representation of the body in the ventroposterior lateral subnucleus (VPL), and the septum between the representation of the hand in medial VPL and the foot representation in lateral VPL, are usually apparent in coronal sections (see Welker, 1973, for review). A less commonly observed septum is found between the most lateral representation of the tail and the larger representation of the foot (Pubols, 1968). Other septa are also apparent, especially those in VPM (Rausell and Jones, 1991; Kaas, 2008). Previously, Welker and Johnson (1965) described vertical septa separating the hand subnucleus of VPL of raccoons into five populations of neurons representing the five digits of the hand in a mediolateral sequence (also see Wiener et al., 1987). We have also observed additional septa within the hand representation of VPL in primates, and this motivated a more systematic study. Here we demonstrate narrow, vertical septa that separate individual digit representations in VPL in members of three major branches of the primate radiation (prosimians, New World monkeys, and Old World monkeys).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The ventroposterior nucleus (VP) of the thalamus was examined for the existence of visually apparent compartments in two macaque monkeys (Macaca radiata and Macaca fascicularis), two owl monkeys (Aotus trivirgatus), two squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus and Saimiri boliviensis), and three prosimian galagos (Otolemur garnetti). The cortical connections of compartments of the hand representation in medial VPL were determined by injecting tracers into the representations of the digits in area 3b of one squirrel monkey and one prosimian galago. All research was conducted in compliance with the guidelines established by the National Institutes of Health and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Vanderbilt University.

Multiunit microelectrode mapping and tracer injections

Tracers of anatomical connections were injected into physiologically defined digit representations in area 3b of one squirrel monkey and one prosimian galago. The topographic representations of the glabrous hand in dorsolateral area 3b of somatosensory cortex of squirrel monkeys and galagos have been well established by microelectrode mapping methods (Carlson and Welt, 1980; Sur et al., 1980, 1982; Wu and Kaas, 2003) and more recently by optical imaging (Chen et al., 2005, 2009) in squirrel monkeys. As in other monkeys, digits 1–5 are represented in a lateral to medial sequence in rostral area 3b, and the pads of the palm are represented adjacently in caudal area 3b. In the present experiment the animals were initially anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (10–25 mg/kg, intramuscularly) and secured in a stereotaxic head holder. A local anesthetic was applied to the ears and subcutaneous skin with lidocaine hydrochloride and animals were transitioned to inhalation anesthesia (1–2% isoflurane in oxygen). Under aseptic surgical conditions the skull over somatosensory cortex was removed and the dura was retracted. The cortex near the shallow central sulcus was digitally photographed so that microelectrode penetrations and injection sites could be localized relative to the brain surface. A low impedance (1 MΩ) tungsten microelectrode was inserted perpendicularly into the cortex at multiple sites and multiunit recordings were used to map receptive fields based on activity driven by light contact on the skin with fine probes (see Qi et al., 2002). Small amounts (0.02 μL) of cholera toxin subunit B (1% CTB, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in sterile distilled water were injected into cortical regions representing digits 2 and 4 at depths of 600–1,000 μm using a 1-μL Hamilton syringe fitted with a glass pipette drawn to a fine tip. Fluoro-ruby (10% FR, 0.02 μL; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was injected in a similar manner into the area 3b representation of digits 1, 3, and 5. Similarly in the galago, small amounts (0.1 μL) of CTB conjugated with Fluoro-emerald (1% Alexa 488, Invitrogen) in phosphate buffer (PB) were injected into cortical regions representing digit 1 in the left hemisphere and the regions representing digits 1 and 3 in the right hemisphere at depths of 600–800 μm. Fluoro-ruby (0.1 μL) was injected into the representation of the palmar pad 1 (P1) in the left hemisphere and the representations of digits 2 and 4 of the right hemisphere. Then the dura was replaced and covered with Gelfilm, the opening in the skull was secured with an artificial bone flap of dental cement, and the skin was sutured. After prophylactic antibiotics and analgesic were given, the animal was carefully monitored while it recovered from anesthesia. Ten to 12 days later the animals were euthanized and the brains retained for processing.

Histological procedures

In order to process the brain tissue the primates were injected with a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (80 mg/kg) and, when areflexive, perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, ph 7.4), followed by 2–4% paraformaldehyde in PB, and 10% sucrose solution and 2–4% paraformaldehyde in PB. The brains were removed and submerged in a 30% sucrose solution for cryoprotection overnight. The thalamus was cut in the coronal plane in 40-μm thick sections on a freezing microtome. Sections through the thalamus were divided into five series, with each series processed for anatomical tracers or for different histological features.

Thalamic sections were processed for cytochrome oxidase or Nissl substance according to standard protocols. A further set of sections was processed for vesicular glutamate transporter 2 using a mouse monoclonal anti-vGluT2 antibody (Chemicon, now part of Millipore, Biller-ica, MA); see Wong and Kaas (2008) for details. Another set of sections was processed for parvalbumin (PV, mouse monoclonal antibody, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Antibody characterization

All antibodies used in this study were previously characterized and their details are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Antibodies Used in the Study

| Antigen | Raised in | Immunogen | Source | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parvalbumin | Mouse (monoclonal) | Purified frog muscle parvalbumin | Sigma (P3088) | 1:2,000 |

| vGluT2 | Mouse (monoclonal) | Recombinant protein from rat vGluT2: full length | Millipore (MAB5504) | 1:2,000 |

Parvalbumin

The mouse monoclonal antiparvalbumin antibody specifically recognizes the calcium binding site of parvalbumin (MW = 12 kDa) from human, bovine, pig, canine, feline, rabbit, rat, and fish on a 2D gel (manufacturer’s technical information). This protein reveals a different subset of GABA-immunoreactive interneurons from calbindin protein (Van Brederode et al., 1990). Immunohistochemistry in the present study shows a pattern of cellular staining and distribution in the VPL that is identical to a previous description (Rausell et al., 1992).

vGluT2

A mouse monoclonal anti-vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (vGluT2) antibody was used, clone 8G9.2 (Millipore, MAB5504). This antibody stained a single band of 56 kDa molecular weight in western blots of mouse brain lysates as shown by the manufacturer. In western blots obtained by our collaborators at Vanderbilt University, the antibody stained a single band of 56 kDa molecular weight in cerebellar tissue from a squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) and from a macaque monkey (Macaca fasciculus). Previous reports indicate that VGluT2 immuno-staining reveals the thalamocortical terminations in layer 4 of the cortex in rats (Fujiyama et al., 2001), ferrets (Nahmani and Erisir, 2005), squirrels (Wong and Kaas, 2008), tree shrews (Wong and Kaas, 2009a), short-tailed opossums (Wong and Kaas, 2009b), galagos (Wong and Kaas, 2010), and macaque monkeys (Hackett and de la Mothe, 2009), as well as the brainstem terminations in the thalamus of rats (Kaneko and Fujiyama, 2002) and squirrels (Wong et al., 2008). The antibody showed the same pattern of staining in layer 4 of sensory cortex in the present materials (not shown) as previously reported in macaque monkeys (Hackett and de la Mothe, 2009) and in galagos (Wong and Kaas, 2010).

Additional processing was necessary for cases with tracer injections. In order to visualize neurons and axon terminals labeled by the CTB injections, relevant thalamic and cortical sections were processed according to the protocol of Angelucci et al. (1996) using peroxidase-based immunohistochemistry with goat anti-CTB (List Biological Labs, Campbell, CA, 1:4,000). Sections used for visualizing the fluorescent tracers FR and CTB conjugated with Fluoro-emerald (Alexa 488) were mounted on glass slides without further processing after sectioning.

Separate sets of serial sections were processed for cytochrome oxidase (CO; Wong-Riley, 1979), Nissl substance (thionin), and vGluT2 to reveal area 3b, or were processed for the anatomical tracers.

Data analysis

Distributions of neurons labeled with FR, Alexa 488, and CTB in the thalamus were plotted with a fluorescent/ brightfield microscope using Neurolucida (MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT). Processed sections were also viewed under a Nikon E800 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) and digital photomicrographs of sections were acquired using a Nikon DXM1200 camera (Nikon) mounted on the microscope. The digitized images were adjusted for brightness and contrast using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA), but they were not otherwise altered. Nissl, CO, and vGluT2-stained sections were used to delineate the subdivisions of the ventroposterior nucleus. Area 3b was defined in sections processed for CO and Nissl staining. Drawings of areal and nuclear boundaries in cortical and thalamic sections stained for architecture were aligned with tracer plots of labeled cells using common blood vessels and landmarks.

RESULTS

Here we present evidence that visible septa in VPL of primates separate five groups of cells, with each group representing a digit of the hand from 1–5 in a mediolateral sequence. The results are presented in three parts. In the first part we present brain sections processed for CO or vGluT2 that illustrate septa in the region of the hand representation within VPL of squirrel monkeys. We next show the relationship of regions between the VPL septa to regions densely labeled by the injection of tracers into the representation of digits in area 3b of somatosensory cortex of one squirrel monkey. In addition, we illustrate the results from our recordings from area 3b that demonstrate that our injections were correctly placed. In the second part we demonstrate that similar septa are apparent in VPL of owl monkeys and macaque monkeys. In the final part we show that these isolating septa are also apparent in VPL of prosimian galagos, and that injections of tracers in digit representations of area 3b indicate that the digits are represented in a mediolateral sequence in VPL, as in monkeys. Thus, septa separate the representations of individual digits in the VP complex of many, if not all, primates. As many other septa are apparent in VP, it is likely that they also separate groups of cells corresponding to representations of different parts of the body.

Septa separating representations of digits in VP of squirrel monkeys

Our present investigation was guided by the results of a previous microelectrode recording study demonstrating that digits 1–5 are represented in a mediolateral sequence in the hand subnucleus of VP in squirrel monkeys (Kaas et al., 1984). The hand subnucleus of VP is easily located in the ventral part of VPL, just medial to the conspicuous cell-poor septum that is widely recognized as separating VPM from VPL (e.g., Jones, 2007; Kaas, 2008). We illustrate this and other limiting septa in coronal brain sections processed for CO and vGluT2. As CO is highly expressed in groups of neurons of high metabolic activity (Wong-Riley, 1979), and vGluT2 is densely expressed in the synaptic terminals of medial lemniscus axons in VP (Kaneko and Fujiyama, 2002), both of these preparations reveal cell-poor septa in VP where little CO activity occurs and few medial lemniscus axons terminate.

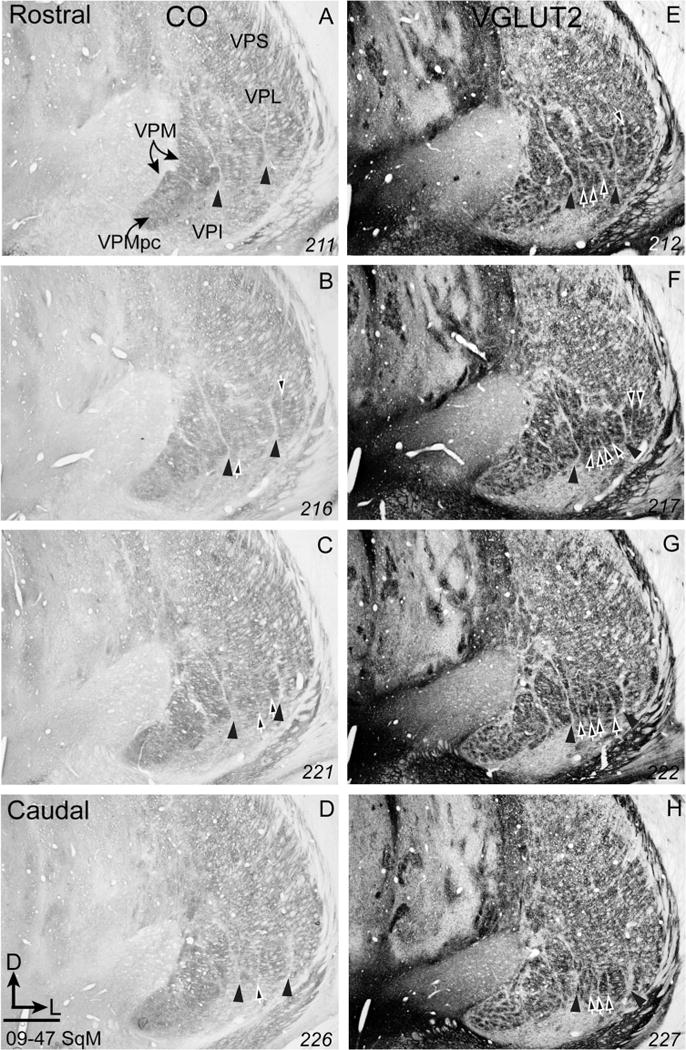

In CO-stained sections, a vertical septum clearly separates most of VPM from VPL (Fig. 1, arrowheads in all panels). This septum is equally apparent in sections processed for vGluT2 (Fig. 1E). A less obvious and less widely recognized septum separates the hand subnucleus from the more lateral foot subnucleus (see the vertical septum indicated by one arrow in Fig. 1E and two arrows in Fig. F just lateral to the arrowheads). Other septa are apparent in VPM and other parts of VPL, but the septa relevant to the present report are marked by the four arrows in the hand subnucleus of VPL (Fig. 1F, G). These four septa are variably apparent through the rostrocaudal extent of VPL, with all four being most visible in sections through the middle of the nucleus. The locations and vertical orientation of the four septa suggest that they separate cell groups representing the five digits of the hand. The most medial cell group, presumably representing digit 1, is quite narrow in the rostral part of VPL, in agreement with microelectrode recording data revealing that the representation of digit 1 is most narrow or missing near the rostral margin of VPL (Kaas et al., 1984). Fewer septa are apparent in the foot subnucleus of VPL (lateral arrows in Fig. 1E, F), but the results suggest that the representations of at least some of the toes are separated by septa.

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs of coronal sections through the ventroposterior nucleus of the thalamus of squirrel monkey (09–47 SqM) processed for cytochrome oxidase (CO, A–D) or vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (vGluT2, E–H). The vGluT2-immunoreacted dense patches are separated by cell-poor septa, revealing a modular organization that corresponds to representations of body parts. Arrowheads in all panels point to septa separating the face subnucleus from the hand subnucleus, and separating the hand subnucleus from the foot subnucleus. White arrows in panels B–H point to cell-poor septa that separate the representations of individual digits or individual toes. Section numbers are in the bottom right corner of each panel. Scale bar = 1 mm.

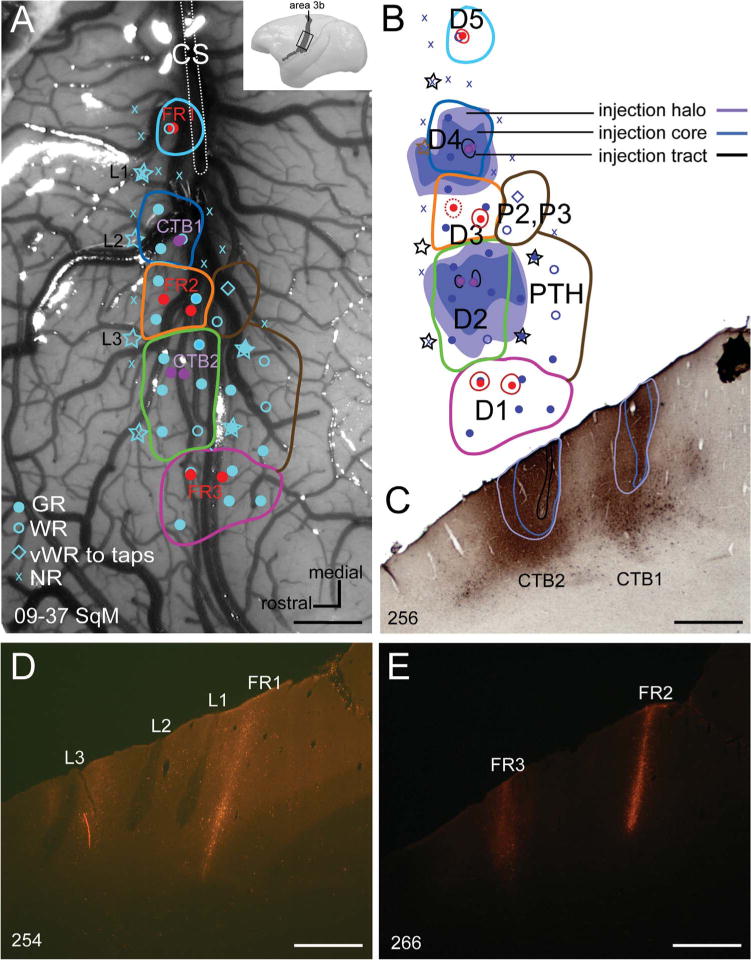

Injections of retrograde and bidirectional tracers into the cortical representations of digits in primary somatosensory cortex (area 3b) of one squirrel monkey confirmed that the five separated groups of cells each represent one of the five digits. The locations of electrode penetrations where neurons were activated by light taps on digits or pads of the palm are indicated on a photograph of the exposed somatosensory cortex (Fig. 2A). The probable boundaries of digit representations are outlined based on electrophysiological mapping. Stars indicate the locations of electrolytic lesions to mark cortical locations that we could later identify in coronal brain sections as an aid to aligning physiological and anatomical results. Injections of FR were placed in the representations of digits 1, 3, and 5 with a micropipette advanced at the same angle as the recording electrode that identified the digit representations. Other injections of CTB were made into the representations of digits 2 and 4. Although the microelectrode and tracer pipette penetrations were at a slight angle from perpendicular to the cortical layers, they were at the same angle so that the parts of the injections that were in the layer 4 uptake zone were in the same locations where the layer 4 recordings identified the digit representations. Figure 2B shows the relationship of electrode penetrations, injection sites, and microlesion sites to the probable boundaries of digit representations. The spread of CTB in cortex (also see Fig. 2C), as reconstructed from serial sections, is also shown. The spread of FR was very limited (Fig. 2D, E).

Figure 2.

A: Photomicrograph of the explored region in somatosensory area 3b of a squirrel monkey (09–37 SqM) shows the locations of microelectrode penetrations (blue symbols), the injection sites of tracers cholera toxin subunit B (CTB, purple dots) and Fluoro-ruby (FR, red dots), and the electrolytic lesions to mark areal borders (stars). Blue dots mark good responses; blue open circles mark weak responses; blue diamonds mark very weak responses to hard taps; x’s mark microelectrode penetrations with no responses. B: A reconstruction of the somatotopic organization of the explored region of cortex. The extent of CTB injection cores (blue), halos (purple), and tracts (black) are indicated as reconstructed from a series CTB-immunoreacted sections. Symbols as in panel A. C: A coronal section shows two CTB injection cores (blue outline), halos (purple outline), and tracts (black outline). CTB1 was in the representation of digit 4, whereas CTB2 was in the representation of digit 2, in area 3b. D: An adjacent coronal section under fluorescent microscopy shows the FR injection site (FR1) placed into the representation of digit 5 in area 3b, and three electrolytic lesions (L1 – L3). E: A coronal section under fluorescent microscopy shows two FR injection sites placed into the representations of digit 3 (FR2) and digit 1 (FR3) in area 3b. CS, central sulcus; D1–5, digits 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5; P2–P3, palmar pads 2 and 3; PTH, pad thenar. Scale bars = 1 mm.

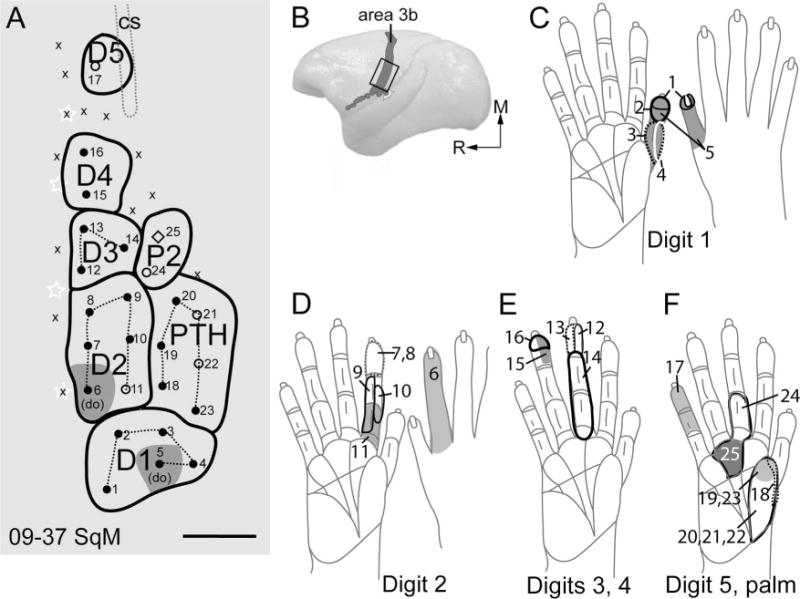

Receptive fields for neurons at recording sites in the hand representation of area 3b are shown in Figure 3. The cortical locations of the electrode penetrations are shown in Figure 3A, with a dorsolateral view of area 3b of the left cerebral hemisphere in Figure 3B. The box indicates the area of cortex in Figure 3A. The recordings indicate the locations of representations of each of the five digits and the thenar and palmar pads. As the light taps on the digits and palm provided above threshold stimulation, the receptive fields were a little larger than those obtained with near-threshold stimulation (see Sur et al., 1982), but they were confined to single digits. When the recording sites were related to cortical histology, all recording sites were in area 3b (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic drawings show receptive fields mapped from the same case as in Figure 2. A: Somatotopic map shows the locations of microelectrode penetrations in area 3b. B: Dorsolateral view of a squirrel monkey brain shows the location of area 3b (gray shading). C–F: Receptive fields obtained with microelectrode recordings are outlined on drawings of the glabrous and dorsal sides of the hand of a squirrel monkey. Numbers on the drawings of the hands indicate the receptive fields recorded from the respective microelectrode penetrations in panel A. do, dorsum; M, medial; R, rostral. For other conventions, see Figure 2. Scale bar = 1 mm.

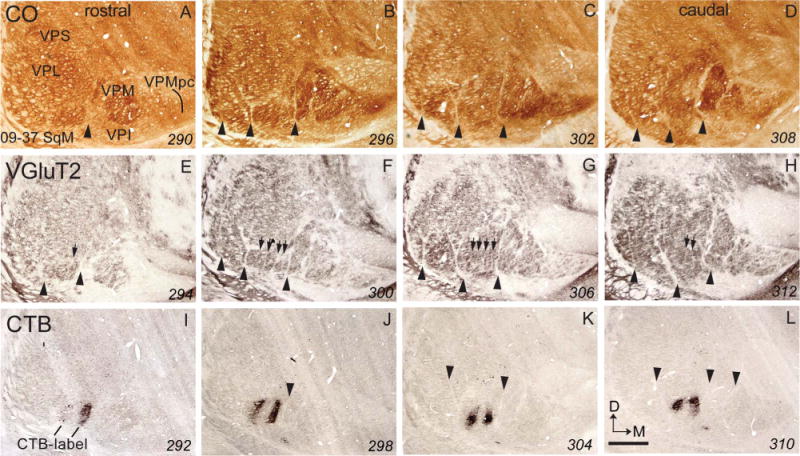

The CTB injections in the cortical representations of digits 2 and 4 labeled two vertically elongated cylinders of cells and axon terminals in VPL (Fig. 4). These foci of label extended over a number of coronal brain sections, which were carefully matched with adjacent or next-to-adjacent brain sections processed for vGluT2 or CO. Septa separating the hand subnucleus and the face subnucleus of VPL are apparent in CO and vGluT2 sections. Moreover, vGluT2-processed sections best revealed the modular structure of VP, which was less clear in CO-stained sections. Five vGluT2 dense ovals separated by narrow, vertical unstained septa in the hand subnucleus of VPL are most obvious in a vGluT2 section (Fig. 4), where the four internal septa are marked by arrows. Parts or all of the five vertical ovals in the band subnucleus can be seen in other vGluT2 processed sections, and to a lesser extent, in the CO sections. In the sections where the ovals can be clearly identified, the second and fourth ovals (counted from medial to lateral) align perfectly with ovals of CTB label resulting from injections in the cortical representation of digits 2 and 4. Previous multiunit recordings from the thalamus show that digits 1–5 are represented in a mediolateral sequence in the hand sub-nucleus of VPL (Kaas et al., 1984); thus, vGluT2-stained ovals 2 and 4 represent digits 2 and 4 respectively. A small focus of label was also apparent in VPI.

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of coronal sections processed for CO (A–D), vGluT2 (E–H), or CTB (I–L) through the ventroposterior nucleus of the thalamus of a squirrel monkey (09–37 SqM). Arrowheads in CO, vGluT2, and CTB panels point to septa that separate the hand subnucleus from the hindlimb subnucleus, and septa that separate the hand subnucleus from the face subnucleus. Arrows in the vGluT2 panels point to septa that separate individual ovals within the hand subnucleus. The dark patches in the CTB sections are CTB-labeled cells and fiber terminals from tracer injections into the representations of digits 2 and 4 in area 3b. The patches of label are located within the 2nd and 4th ovals in the hand subnucleus of VP in the vGluT2 panels. The numbers in the lower right corner are the section numbers. VPI, ventroposterior inferior nucleus of the thalamus; VPL, ventroposteriolateral nucleus of the thalamus; VPM, ventroposterior medial nucleus of the thalamus; VPMpc, parvocellular part of the ventroposterior medial nucleus of the thalamus; ventroposterior superior nucleus of thalamus. For other conventions, see Figure 1. Scale bar = 1 mm.

FR was injected into the cortical territories of digits 1, 3, and 5 in the same case (Fig. 5). As expected, the cells labeled by the FR injections were almost completely confined to ovals 1 and 3, although a few labeled cells were in ovals 2 and 4. The injection in the cortical territory of digit 5 only labeled two cells in oval 5. In addition, a few CTB and FR-labeled cells were more dorsal in VPL.

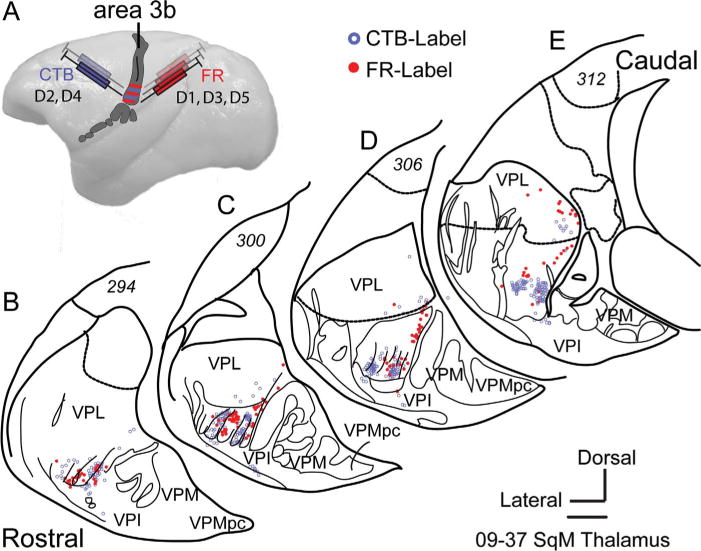

Figure 5.

A: Dorsal view of a squirrel monkey brain shows alternating injections of CTB and FR into the representations of digits 2 and 4, and the representations of digits 1, 3, and 5 in area 3b. B–E: Tracings of coronal sections show the distributions of CTB-labeled and FR-labeled cells in the hand subnucleus of the ventroposterior nucleus of the thalamus. For other conventions, see Figures 1 and 4. Scale bar = 1 mm.

We interpret these results as evidence that digits 1–4 are represented in ovals 1–4, respectively. The paucity of labeled neurons in oval 5 reflected poor uptake or transport of the FR tracer in the cortical representation of digit 5. Cells labeled more dorsally in VPL, or in ovals 2 and 4 by FR suggest some spread of tracer in cortex, or that thalamocortical terminations from each thalamic oval are not completely confined to the representation of a single digit.

Septa separating representations of digits in VP of owl monkeys

Cell-poor septa divide VP of owl monkeys into subdivisions that represent body parts much as they do in squirrel monkeys. Nissl, vGluT2, and CO-processed brain sections all reveal some of these septa, but they are most apparent in sections processed for vGluT2 (Fig. 6). A narrow septum separates VPMpc from VPM, and other major septa separate the hand subnucleus from VPM, the hand subnucleus from the foot subnucleus, and the foot subnucleus from the tail subnucleus (arrowheads in Fig. 6). Within the hand subnucleus, additional septa separate the territories of the digits. These septa are only faintly apparent in the Nissl and CO preparations, but they can be identified throughout VPL in sections processed for vGluT2. There are only hints of septa separating representations of the toes in the foot subnucleus. Similar results for a second owl monkey (Fig. 7) reveal clear septa separating representations of the digits and separating representations of the toes in the vGluT2 preparations, but not in the CO preparations, although the major septa that isolate the tail, foot, hand, and face representations are apparent (Fig. 7). Although the somatotopic organization of VP in owl monkeys has not been determined in microelectrode mapping experiments, we can surmise from results in squirrel monkeys (Kaas et al., 1984) that toes and digits are represented from 1–5 in mediolateral sequences.

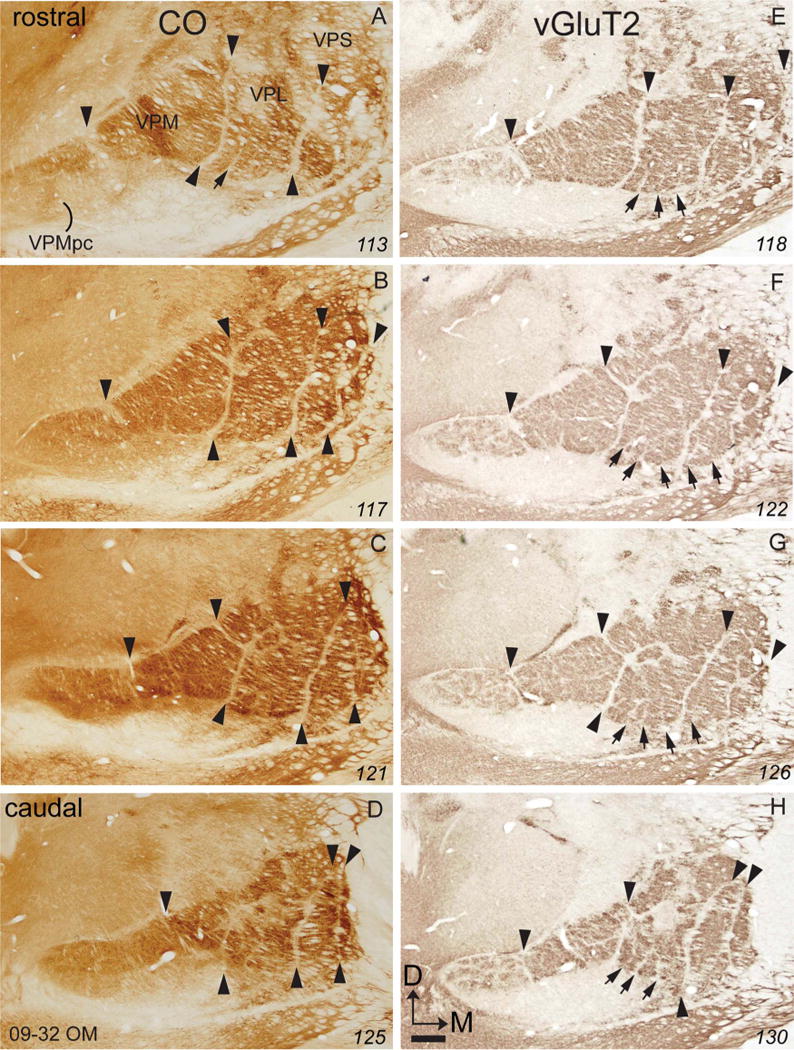

Figure 6.

Photomicrographs of coronal sections processed for CO (A–D) or vGluT2 (E–H) through the ventroposterior nucleus of the thalamus of an owl monkey (09–32 OM). For conventions, see Figures 1 and 4. Scale bar = 1 mm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at =wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

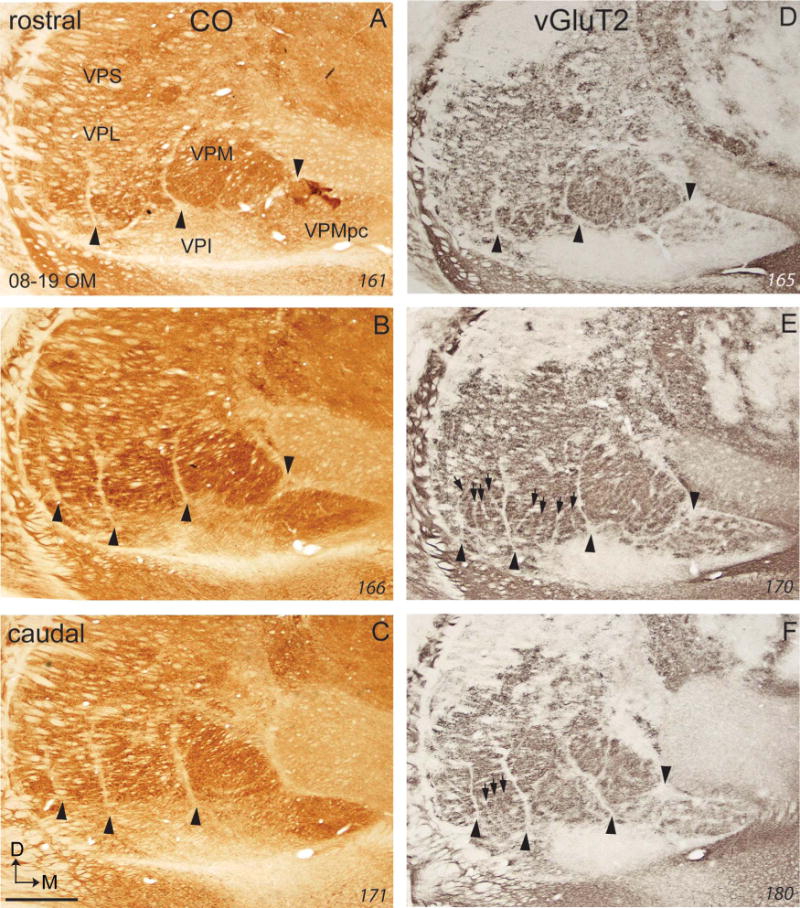

Figure 7.

Photomicrographs of coronal sections processed for CO (A–C) or vGluT2 (D–F) through the ventroposterior nucleus of the thalamus of an owl monkey (08–19 OM). For conventions, see Figures 1 and 4. Scale bar = 1 mm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at =wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

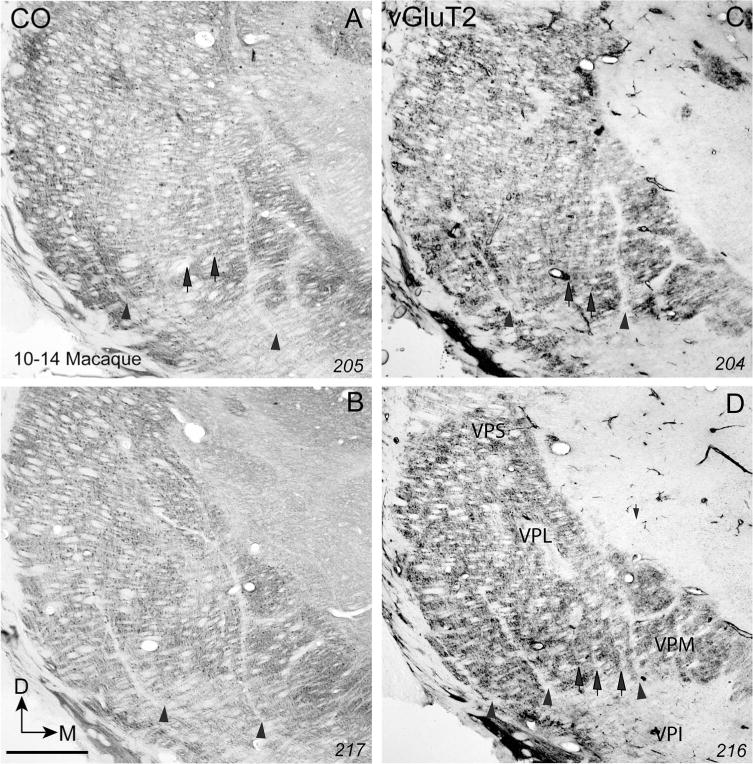

Septa separating representations of digits in VP of macaque monkeys

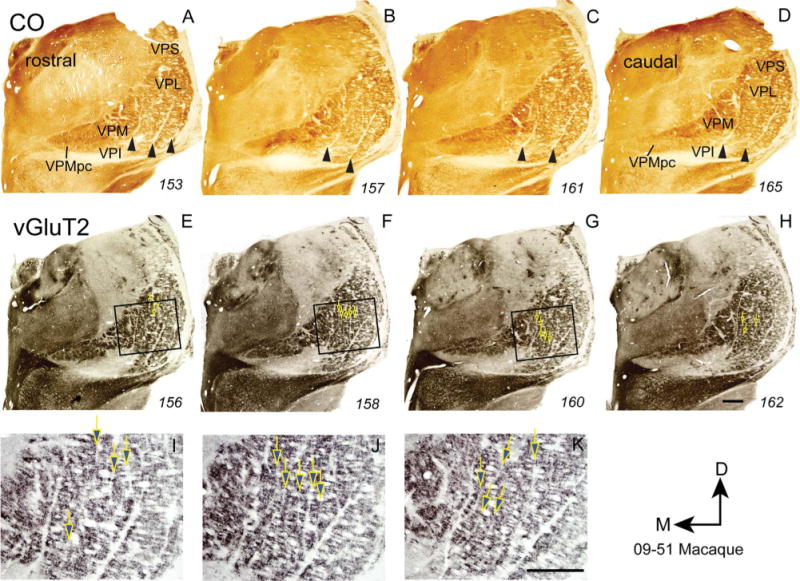

As in New World monkeys, narrow, poorly stained septa separate VPM, VPL hand, and VPL foot subnuclei from each other in CO and vGluT2 preparations of VP in macaque monkeys (Figs. 8, 9). In the hand subnucleus of VPL, long, nearly vertical septa are visible in the vGluT2 preparations. In contrast to the cell groups isolated by such septa in New World owl and squirrel monkeys, these cell groups do not form elongated ovals, but instead form columns 4 to 6 times longer than their widths. As in other primates, the columns likely correspond to representations of digits 1–5 from medial to lateral. The septa within the hand subnucleus, and the septa that separate VPM from VPL, and separate the foot and hand subnuclei are much more distinct in vGluT2 than in CO or Nissl preparations. Septa dividing the foot subnucleus into territories for each toe were not apparent.

Figure 8.

Photomicrographs of coronal sections processed for CO (A–D) or vGluT2 (E–H) through the ventroposterior nucleus of the thalamus of a macaque monkey (09–51 MM). Photomicrographs I–K show the boxes in E–G at a higher magnification. For conventions, see Figures 1 and 4. Scale bars = 1 mm. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at =wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Figure 9.

Photomicrographs of coronal sections processed for CO (A,B) or vGluT2 (C,D) through the ventroposterior nucleus of the thalamus of a macaque monkey (10–14 MM). For conventions, see Figures 1 and 4. Scale bar = 1 mm.

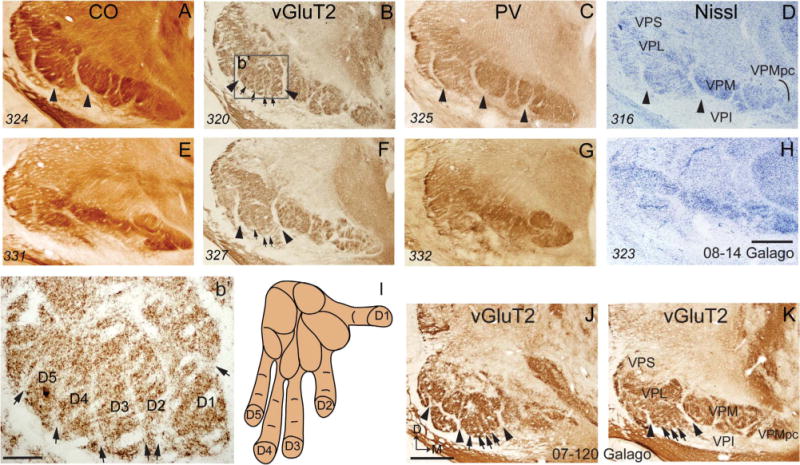

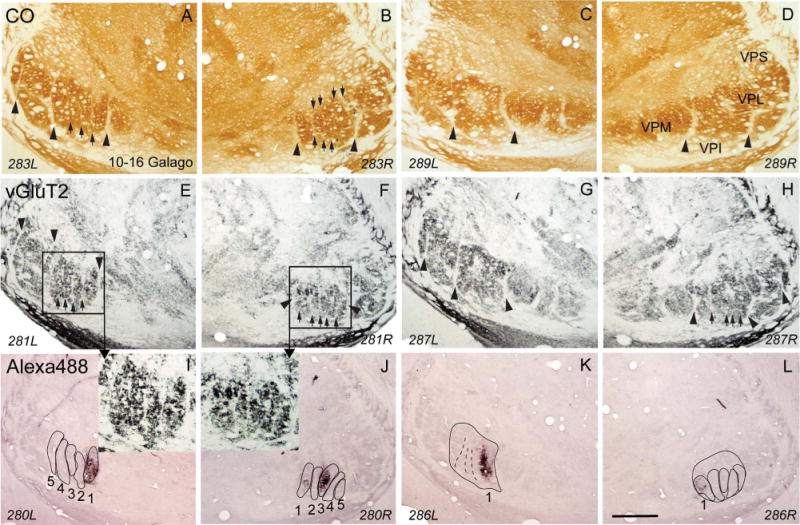

Septa separating the representations of digits in VP of prosimian galagos

The major subdivisions of VP in prosimian galagos are apparent in Nissl, CO, PV, and vGluT2 preparations (Fig. 10). Major septa separate the hand subnucleus from the foot subnucleus and the face subnucleus (VPM). As prosimian galagos use their hands less skillfully to manipulate and explore objects than monkeys (Carlson, 1990), territories in VPL for digits were expected to be less distinct than in monkeys. In support of this supposition, territories isolated by septa were not apparent in the hand subnucleus in Nissl, CO, and PV preparations.

Figure 10.

Photomicrographs of coronal sections processed for CO, vGluT2, parvalbumin (PV), or Nissl through the ventroposterior nucleus of the thalamus of a galago. Digits are numbered on the hand in panel I, and cell groups corresponding to each digit are numbered in panel b′, which is a magnified view of the part of VP box (b′) in panel B. For other conventions, see Figures 1 and 4. Scale bars = 1 mm in A–H,J,K; 0.2 mm in b’. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at =wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

However, in favorable coronal brain sections through the anterior half of VP, digit territories were visible in vGluT2 preparations (boxes b’ and b’ in Fig. 10). Five territories were isolated by vertical septa. By position, these territories likely correspond to digits 1–5 in a mediolateral sequence.

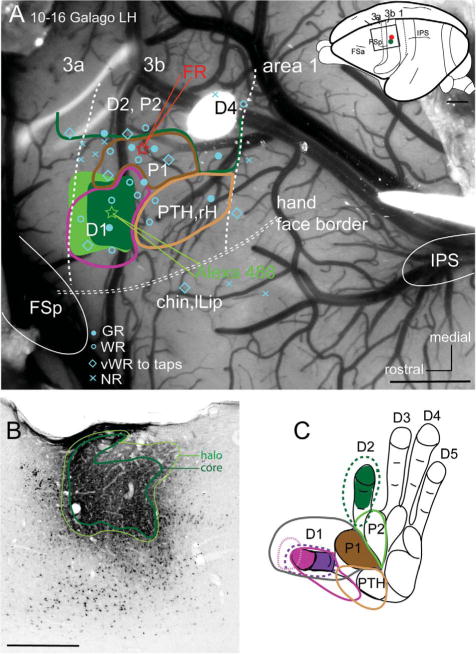

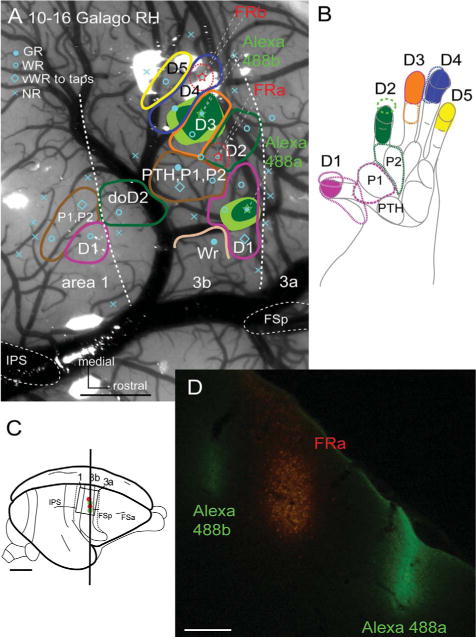

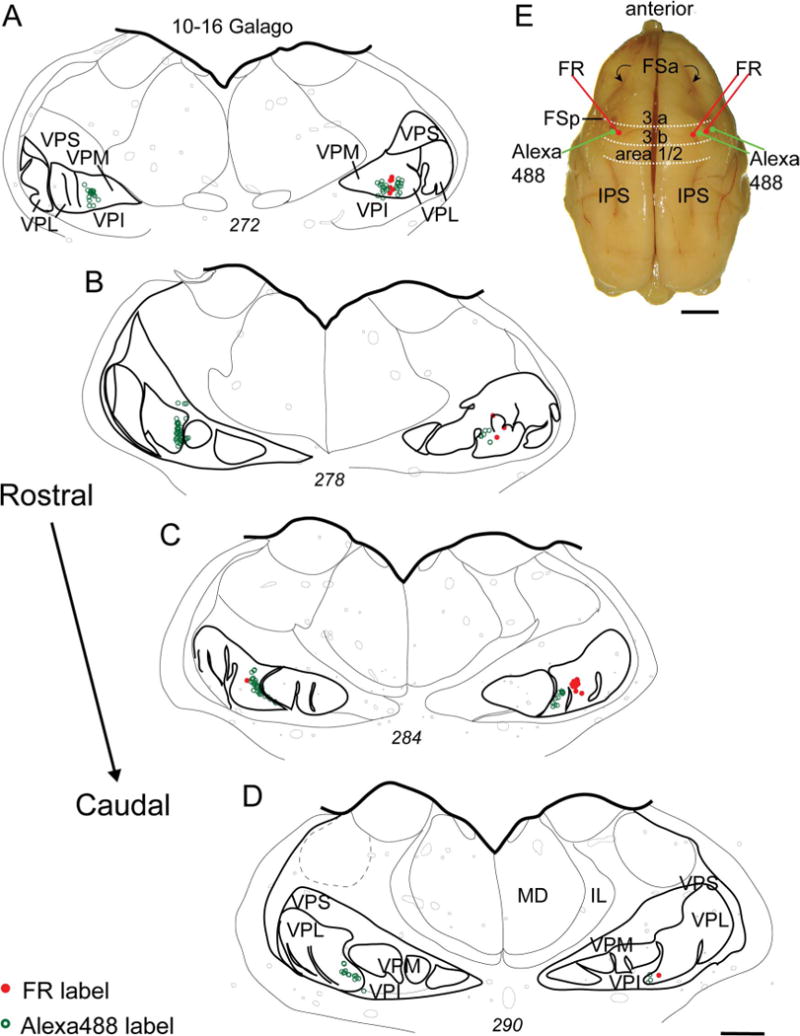

In order to directly identify territories for digits in the hand subnucleus of VP in galagos, we injected tracers into representations of the digits in cortical area 3b in one galago. Microelectrode recordings in the left cerebral hemisphere were used to identify the cortical representations for digits 1, 2, and the palmar pads (Fig. 11A, C). An injection of Alexa 488 was confined to the representation of digit 1 (Fig. 11B), and an injection of FR was confined to the representation of the palmar pad 1 (P1). In the right cerebral hemisphere, representations of digits 1 to 5 were identified by microelectrode recordings and Alexa 488 was injected into the representations of digits 1 and 3, whereas FR was injected into the representations of digits 2 and 4 (Fig. 12D). Cells labeled in the thalamus are shown relative to the series of ovals separated by septa in the hand subnuclei (Fig. 13). CTB injected into the representation of digit 1 in the left hemisphere labeled the most medial oval of the five in the hand subnucleus of VP. CTB injected into the representations of digits 1 and 3 in the right hemisphere labeled cells in the most medial oval and the middle oval (3) of the hand subnucleus of VPL. By comparing the results from the right and left hemispheres, we conclude that thalamic oval 1 projects to the cortical representation of digit 1, and thalamic oval 3 projects to the digit 3 representation.

Figure 11.

A: Photomicrograph of the explored region of area 3b in the left hemisphere of a galago (10–16) shows the locations of microelectrode penetrations (blue symbols). Blue dots mark good responses; blue open circles mark weak responses; blue diamonds mark very weak responses to hard taps; x’s mark microelectrode penetrations with no responses. Injections into the representations of digit 1 (Alexa 488, green star) and the first palmar pad (Fluoro-ruby, red star) are also shown. The extent of the Alexa 488 injection core and halo (shades of green) were reconstructed from a series of coronal CTB immunoreacted sections. Two vertical dashed lines indicate the areal borders of 3b with areas 3a and 1 based on microelectrode recordings, a horizontal double dashed line indicates the border of hand and face representations. A dorsolateral view of a galago brain on the upper right shows the location of somatosensory area 3b, with a box outlining the cortex viewed in the photomicrograph. B: A coronal CTB immunoreacted section showing core and halo after the Alexa 488 injection into area 3b. C: Receptive fields obtained with microelectrode recordings in panel A are outlined on the drawing of the right glabrous hand of a galago. 3a, area 3a; 3b, area 3b; FSa, frontal sulcus anterior; FSp, frontal sulcus posterior; IPS, intraparietal sulcus; lLip, lower lip; P1, palmar pad 1; rH, radial hand. For other conventions, see Fig. 2. Scale bars = 1 mm in A; 0.5 mm in B.

Figure 12.

A: Photomicrograph of the explored region of area 3b in the right hemisphere of a galago (10–16) shows the locations of microelectrode penetrations (blue symbols). Blue dots mark good responses; blue open circles mark weak responses; blue diamonds mark very weak responses to hard taps; x’s mark microelectrode penetrations with no responses. Injections into the representations of digits 1 and 3 (Alexa 488, green stars) and digits 2 and 4 (Fluoro-ruby, red stars) are also shown. The extent of the Alexa 488 injection core and halo (shades of green) were reconstructed from a series coronal CTB immunoreacted sections. Two vertical dashed lines indicate the areal borders of 3b with areas 3a and 1 based on microelectrode recordings. B: Receptive fields obtained with microelectrode recordings in panel A are outlined on the drawing of the right glabrous hand of a galago. C: A dorsolateral view of a galago brain shows the location of somatosensory area 3b, with a box outlining the cortex viewed in the photomicrograph. D: Darkfield fluorescent microscopy of a coronal section showing the injection sites after Alexa 488 injected into the cortex representing digits 1 (Alexa 488a) and 3 (Alexa 488b) of area 3b, and an injection of FR (FRa) into the representation of digit 2 in area 3b. For other conventions, see Figure 11. Scale bars = 1 mm in A; 5 mm in C; 250 μm in D.

Figure 13.

Photomicrographs of coronal sections processed for CO (A–D), vGluT2 (E–H), or CTB (I–L) through the ventroposterior nucleus of the thalamus of galago (10–16). Section numbers at the bottom of each panel also indicate the left (L) and right (R) side of the thalamus. The dark patches of label in CTB immunoreacted sections (I,K) were produced by tracer injections into cortical representation of digit 1 in area 3b of the left hemisphere. Similarly, the dark patches in panels J,L were produced by CTB injections into the representations of digits 1 and 3 in area 3b of the right hemisphere. The locations of labeled patches correspond to the dark ovals in the hand subnucleus of VPL in vGluT2 sections. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, are the ovals for the corresponding digits. For other conventions, see Figures 1 and 4. Scale bar = 1 mm.

The FR injections were less effective in this case, but they provided some additional information (Fig. 14). For the left hemisphere, the palmar pad 1 injection labeled only one cell in VP, and that was on the dorsal margin of the digit 1 oval in VP, providing weak evidence that pad 1 is not represented by any of the five ovals in the ventral half of the hand subnucleus, but is represented dorsal to the digit 1 oval, as expected from detailed physiological results in VP of squirrel monkeys (Kaas et al., 1984). In the right hemisphere, only one of the two injections of FR was effective. The injection labeled neurons in oval 2 that were located between the neurons labeled by CTB injections in the cortical representations of digits 1 and 2. Overall, the connection patterns in galagos strongly support the conclusion that the five ovals in the hand subnucleus of VPL of galagos represent digits 1–5, in a mediolateral sequence.

Figure 14.

Corticothalamic connections in galago 10–16 (same case as in Figs. 11–13). A–D: A series of drawings shows the distributions of labeled cells in VPL from injections of FR and Alexa 488 tracers into the representations of the first palmar pad and digit 1 of area 3b in the left hemisphere. The distributions of labeled cells from injections of Alexa 488 into the representations of digits 1 and 3, and injections of FR into the representations of digits 2 and 4 of area 3b of the right hemisphere are also shown. E: Dorsal view of a galago brain showing major sulci and the locations of the injection sites. For other conventions, see Figures 2, 4, and 11. Scale bars = 1 mm in A–D; 5 mm in E.

DISCUSSION

The VP of the thalamus in primates is composed of groups of cells separated by cell-poor septa (see Jones, 2007; Kaas, 2008). Traditionally, these fibrous septa have been revealed in fiber stains for myelin (e.g., Welker and Johnson, 1965). The septa are also apparent as regions of weak staining in a numbers of other preparations, including those for CO, and PV. A prominent vertical septum, the long recognized arcuate lamella, separates the medial part of VP (VPM) that represents the face and mouth from the lateral parts (VPL) that represents the rest of the body. A more lateral septum separates a medial subnucleus of VPL that represents the hand from a more lateral subnucleus that represents the foot. Here we show that these and other septa are especially prominent in brain sections processed for vGluT2, which is expressed in the synaptic terminals of excitatory neurons in most nuclei of the brainstem and thalamus (e.g., Kaneko and Fujiyama, 2002; Hackett and de la Mothe, 2009; see Fremeau et al., 2004; Liguz-Lecznar and Skan-giel-Kramska, 2007). As vGluT2 is expressed in the synaptic terminations from dorsal columns and trigeminal brainstem nuclei, the effectiveness of vGluT2 preparations in revealing septa in VP likely reflects a lack of synapses in the septa that is using glutamate as a transmitter.

Our focus in this article is on the septa in the hand subnucleus of VPL that separate five vertical ovals or columns of cells that appear to represent each of the five digits, 1–5, in a mediolateral sequence. By injecting retrograde and bidirectional tracers into the representations of the digits in primary somatosensory cortex (area 3b) of a squirrel monkey and a prosimian galago, we provide anatomical evidence that each of the five ovals in hand VPL projects predominantly to the cortical territory of a specific digit. In coronal brain sections through the VP of monkeys and prosimian galagos that have been processed for vGluT2, we show that similar isolating septa exist, suggesting that vGluT2 is a marker that has the potential for revealing the representations of digits, and other body parts, in all primates. Below, we briefly review our present findings in the context of previous studies of the somatotopic organization of VP in primates.

Functional organization of VP in primates

We propose that the septa revealed in the VPL hand subnucleus of primates isolate the representations of five digits and thereby provide precise information on how the digits are represented in VPL. In some instances they also appear to isolate representations of the toes in the foot subnucleus, but this will require experimental verification. Here we compare present results and conclusions on the organization of the hand subnucleus in squirrel monkeys, owl monkeys, macaques, and galagos with results of previous microelectrode mapping studies and studies of cortical connections of VP in these primates.

In squirrel monkeys the most relevant previous study was a detailed microelectrode mapping study of VP somatotopy (Kaas et al., 1984). The summary diagram of VP in that study (Fig. 13, Kaas et al., 1984) portrayed the representation of digits 1–5 in the hand subnucleus as five vertical slabs arranged mediolaterally, with each slab extending dorsally across most of the subnucleus and rostrocaudally across the subnucleus. This proposed organization, which included a more dorsal representation of the palm, and a dorsal subnucleus for the arm and trunk, closely reflects the present results. Note that the isolating septa for digits do not extend to the dorsal margin of the hand subnucleus, and that they are present in a number of coronal sections through the subnucleus. In addition, the dense foci of retrograde label in the subnucleus after injections of tracer in digit representations in area 3b occupied much of the digit territories as marked by septa, without extending beyond them. The toes 1–5, as represented in a similar mediolateral sequence in the foot subnucleus (Kaas et al., 1984), and the sometimes visible vertical septa in the foot subnucleus mark the probable boundaries of these representations.

Other microelectrode mapping studies of VP organization in squirrel monkeys have been less specific on how the digits are represented, as they were focused on the locations of nociceptive neurons (Apkarian and Shi, 1994). However, the limited results regarding the somatotopy of VP seem broadly consistent with the conclusions of Kaas et al. (1984). The organization of the thalamocortical connections of VP has not been explored in any detail in squirrel monkeys, but injections in digit representations along the rostral border of area 3b labeled neurons largely in the ventral half of the hand subnucleus (Cusick et al., 1985), as expected from present and previous results.

Our histological results suggest that the VPL hand subnucleus in owl monkeys is organized very much as it is in squirrel monkeys, as five dorsoventrally orientated ovals in a mediolateral sequence separated by vertical septa. However, there is very little confirming evidence. We know of no microelectrode mapping of VP in owl monkeys, and of only one study of the cortical connections of VP. Lin et al. (1979) identified head, hand, foot, tail, and trunk subnuclei in VP of owl monkeys, and injections of tracers into the representations of digits in area 3b labeled neurons and corticothalamic terminals in the hand subnucleus. The results indicated that neurons across the rostrocaudal extent of the hand subnucleus of VPL project to digit representations in area 3b, but territories for individual digits were not determined. In a smaller New World monkey, the marmoset, microelectrode mapping located the representations of digits 1–5 in a mediolateral sequence in the hand subnucleus of VPL (Wilson et al., 1999). In marmosets, the hand subnucleus of VPL projects to digit representations in area 3b (Krubitzer and Kaas, 1992). Overall, the VPL hand subnucleus appears to be organized in a similar manner in squirrel monkeys, owl monkeys, and marmosets.

Our histological results from macaque monkeys revealed long vertical septa in the hand subnucleus of VPL that suggest that the long and narrow slabs of cells between the septa isolate the representations of individual digits in a mediolateral sequence. Although VP has been explored with microelectrodes in a number of studies in macaques, this conclusion is only weakly supported by such previous results. Early microelectrode recordings demonstrated that the hand and digits were represented in the medial portion of VPL just lateral to VPM, but receptive fields often involved large parts of the hand, and territories for individual digits were not established (Mountcastle and Henneman, 1952; Poggio and Mountcastle, 1963; Loe et al., 1977; Jones et al., 1982). Using vibration and flutter stimuli on the hand and 2-deoxyglucose techniques to reveal the locations of increased metabolic activity in VP, Juliano et al. (1983) concluded that the digits are represented lateral to that of the face and medial to that of the foot. Studies of thalamocortical connections established that injections in the digit-hand representations of area 3b in macaque labeled dorsoventrally orientated slabs of neurons in the hand subnucleus of VPL, but included little about the representations of individual digits (Jones et al., 1979; Nelson and Kaas, 1981; Darian-Smith et al., 1990; Padberg et al., 2009). Likewise, the limited microelectrode mapping of VP in the recent study of Padberg et al. (2009) located representations of digits in VPL just lateral to VPM, but not territories for individual digits. The more extensive microelectrode mapping of VPM by Rausell and Jones (1991) did not include results from VPL, although a subsequent summary diagram based on results from that study portrayed a hand subnucleus on a coronal section with extended dorsoventral territories for digits 1–5 in a mediolateral sequence (fig. 7.9, Jones, 2007). This portrayal of digit representations is in substantial agreement with the present histological evidence from isolating septa that digit representations are more elongated dorsoventrally in VPL than those in New World monkeys. Thus, proportionally more of VP appears to be devoted to representing the digits in macaque monkeys than in owl or squirrel monkeys, or galagos.

In prosimian galagos we also provided histological evidence for vertical septa that divide the hand subnucleus of VPL into five vertically oriented clusters of neurons, and demonstrate via connections with digit representations in area 3b that these five cell groups represent digits 1–5 in a mediolateral sequence. Little has been previously reported on the organization of VP in galagos or other prosimian primates. However, the architecture of VP in Nissl and CO preparations clearly reveal hand, foot, and face subnuclei (Kaas, 2008), but not septa dividing the hand subnucleus into digit territories, as in the present material. In an early study of thalamocortical connections, tracers placed in the hand representation in area 3b of galagos labeled cells in medial VPL next to VPM, whereas tracers in the region of the foot representation labeled neurons more laterally in VPL (Pearson and Haines, 1980). These results are consistent with those obtained after injection of tracers in physiologically identified representations of area 3b in galagos (Franca et al., 2003), but neither study had the resolution to localize the thalamic representations of single digits. In a related study of thalamocortical connections in another prosimian primate, the slow loris, fibrous septa were noted that divided VP into VPM, a hand subnucleus, and a foot subnucleus (Krishnamurti et al., 1972). When electrophysiologically identified portions of area 3b representing the head, hand, or foot were ablated, neurons degenerated in VPM (head), VPL hand subnucleus, or VPL foot subnucleus. Our present results indicate that the digits are represented separately in the hand subnucleus of VPL of galagos, much as they are in New World monkeys. As separate territories for toes in the foot subnucleus are less visible in vGluT2 preparations in galagos, representations of individual toes may be less distinct from each other than those for the digits.

Overall, the results from four species of primates seem to indicate that neurons in VP and area 3b in primates are largely responsive to tactile stimulation of single digits. Indeed, some recording data from area 3b are consistent with this assumption, when stimuli are at near threshold levels (e.g., Pons et al., 1987). Yet, receptive fields can be larger when above threshold stimuli are presented, and the surrounding inhibitory or suppressive receptive field surrounds can be much larger (e.g., Reed et al., 2008). Thus, the highly confined thalamocortical projections demonstrated in this study do not account for larger receptive fields for area 3b neurons that include several digits; such receptive fields may depend on sparser thalamocortical connections, intrinsic connections in cortex, and feedback connections from higher levels of processing. The present results, in which small CTB injections in physiologically identified digit representations in area 3b densely labeled cells and axon terminals in specific digit modules in VPL, may seem inconsistent with previous evidence that there may be considerable convergence and divergence in thalamocortical connections. For example, the terminal arbors of thalamocortical axons in area 3b of monkey have been described as spanning as much as 800–900 μm, or more, along layer 4 (Garraghty et al., 1989; Garraghty and Sur, 1990), and injections placed as much as 1 mm apart in VP produced overlapping zones of labeled terminals in area 3b (Rausell et al., 1998). However, even large arbors in area 3b may be mostly confined to the representations of single digits, and there may not be sufficient uptake of tracers in parts of arbors that are sparsely branched. In addition, it may be difficult to determine the effective uptake zone of tracers injected into the thalamus or cortex. In the present case, for example, retrogradely labeled cells in VPL were more widely distributed after injections of FR than CTB. We suggest that the present results indicate that digit representations in area 3b receive most of their synaptic inputs from neurons in matching digit modules in the hand subnucleus of VP.

Functional significance of isolating septa

There is extensive evidence that septa commonly divide somatosensory representations at both cortical and subcortical levels. Such separating fibers or septa have been described for brainstem, thalamus, and cortical levels of processing for the mystacial vibrissal system of mice and rats (see Killackey, 1980, for review), and for forepaw digit representations at these levels in raccoons (Welker et al., 1964). Isolating septa for the representations of the 11 mobile rays on each side of the nose of the star-nosed mole are found in both S1 and S2 (Catania and Kaas, 1996). In both New and Old World monkeys, septa separating representations of the digits of the hand have been described in the cuneate nucleus of the brainstem (e.g., Qi and Kaas, 2006) and in primary somatosensory cortex (Jain et al., 1998; Qi and Kaas, 2004). The evidence presented here indicates that isolating septa also exist in VP. As such septa exist in the brainstem and thalamus of prosimian galagos, it is possible that they also exist in the cortex. Thus, septa as markers of somatotopic disjunctions are widespread and occur at several levels of processing in the somatosensory system, becoming less apparent or disappearing at higher levels of cortical processing. Such septa may exist in VP of humans and apes, where they would provide useful information on somatotopy.

All these isolating septa in the somatosensory systems of mammals correspond to disruptions in the sensory sheet where groups of receptors that are seldom activated together are represented next to each other. Such disruptions do not occur naturally in the receptor sheet in the cochlea of the auditory system, and thus no isolating septa within brainstem, thalamic, and cortical representations of that receptor sheet have been reported. The visual system is somewhat similar in that the receptor sheet, the retina, is almost continuous. However, the optic nerve head or optic disc does produce a hole in the array of visual receptors, the rods and cones, and this hole is matched by a rod-like discontinuity that is often apparent in the layers of the dorsal lateral geniculate that receive inputs from the hemiretina with the optic disc, that is, from the contralateral eye (Kaas et al., 1973). Of course, in many mammals with highly developed vision, geniculate layers for each of the two eyes are separated from each other by septa.

The functional significance of septa across sensory systems is that they constitute narrow “no-man zones” separating neurons that are activated by different sensory inputs (Kaas and Catania, 2002). Septa likely emerge during development as a result of competition for synaptic space based on neural activity. As postulated in the classical competition model (e.g., Shatz, 1990; Katz and Shatz, 1996; Huberman et al., 2008), when neural inputs are coactivated, their synapses on shared groups of neurons are maintained, while weaker synapses on shared groups of neurons are lost when such coactivation does not occur. As asked some years ago, “Does the skin tell the somatosensory cortex how to construct a map of the periphery” (Van der Loos and Dörfl, 1978)? The answer seems to be “not completely,” but neural activity patterns do fine-tune sensory representations, and sometimes activity patterns separate synaptic contacts between adjoining populations of neurons so completely that isolating septa emerge. For many mammals, much of the refinement of sensory representations and the formation of isolating septa likely occur prenatally or in early postnatal life, when receptor surfaces are not in full use, and yet activity patterns are different enough to refine and disrupt sensory maps. The septa separating digit representations in area 3b of macaques are apparent as early as 2 weeks after birth (Qi and Kaas, 2004). In mice, the dendritic arbors of neurons in the barreloids for facial whiskers in VP are confined to a single barreloid at postnatal day 5, but distal dendrites extend into adjacent barreloids as the mice mature and start to stimulate adjacent whiskers in whisking behavior (Zantua et al., 1996). Thus, the strict isolation of groups of neurons by septa may be compromised when behaviors emerge that emphasize interactions across physically disrupted sensory surfaces, such as those on fingers. The general lack of septa in higher-order cortical somatosensory areas may reflect their relatively late development during postnatal life when behaviors alter earlier cortical activation patterns.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jamie L. Reed for comments on the article and Laura Trice and Chaohui Tang for technical support.

Footnotes

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health (NIH); Grant number: NS 16446 (to J.H.K.); Grant sponsor: Canadian Institutes for Health Research (postdoctoral fellowship to O.A.G.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Angelucci A, Clasca F, Sur M. Anterograde axonal tracing with the subunit B of cholera toxin: a highly sensitive immunohistochemical protocol for revealing fine axonal morphology in adult and neonatal brains. J Neurosci Methods. 1996;65:101–112. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apkarian AV, Shi T. Squirrel monkey lateral thalamus. I. Somatic nociresponsive neurons and their relation to spinothalamic terminals. J Neurosci. 1994;14(11 Pt 2):6779–6795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06779.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M. The role of somatic sensory cortex in tactile discrimination in primates. In: Jones EG, Peters A, editors. Cerebral cortex. 8B. New York: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 451–486. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, Welt C. Somatic sensory cortex (SmI) of the prosimian primate Galago crassicaudatus: organization of mechanoreceptive input from the hand in relation to cytoarchitecture. J Comp Neurol. 1980;189:249–271. doi: 10.1002/cne.901890204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania KC, Kaas JH. The unusual nose and brain of star-nosed mole. BioScience. 1996;46:578–586. [Google Scholar]

- Chen LM, Friedman RM, Roe AW. Optical imaging of SI topography in anesthetized and awake squirrel monkeys. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7648–7659. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1990-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LM, Friedman RM, Roe AW. Optical imaging of digit topography in individual awake and anesthetized squirrel monkeys. Exp Brain Res. 2009;196:393–401. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1861-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark WE. The structure and connections of the thalamus. Brain. 1932;55:406–470. [Google Scholar]

- Cusick CG, Steindler DA, Kaas JH. Corticocortical and collateral thalamocortical connections of postcentral somatosensory cortical areas in squirrel monkeys: a double-labeling study with radiolabeled wheatgerm agglutinin and wheatgerm agglutinin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Somatosens Res. 1985;3:1–31. doi: 10.3109/07367228509144574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darian-Smith C, Darian-Smith I, Cheema SS. Thalamic projections to sensorimotor cortex in the macaque monkey: use of multiple retrograde fluorescent tracers. J Comp Neurol. 1990;299:17–46. doi: 10.1002/cne.902990103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DR, Killackey HP. The organization and mutability of the forepaw and hindpaw representations in the somatosensory cortex of the neonatal rat. J Comp Neurol. 1987;256:246–256. doi: 10.1002/cne.902560205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franca JG, Qi H, Kaas JH. Cortical connections and architecture of the somatosensory thalamus of prosimian galagos. Soc Neurosci Abst. 2003:2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RT, Jr, Voglmaier S, Seal RP, Edwards RH. VGLUTs define subsets of excitatory neurons and suggest novel roles for glutamate. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiyama F, Furuta T, Kaneko T. Immunocytochemical localization of candidates for vesicular glutamate transporters in the rat cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435:379–387. doi: 10.1002/cne.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraghty PE, Sur M. Morphology of single intracellularly stained axons terminating in area 3b of macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1990;294:583–593. doi: 10.1002/cne.902940406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraghty PE, Pons TP, Sur M, Kaas JH. The arbors of axons terminating in middle cortical layers of somatosensory area 3b in owl monkeys. Somatosens. Mot Res. 1989;6:401–411. doi: 10.3109/08990228909144683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett TA, de la Mothe LA. Regional and laminar distribution of the vesicular glutamate transporter, VGluT2, in the macaque monkey auditory cortex. J Chem Neuroanat. 2009;38:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidarliu S, Ahissar E. Size gradients of barreloids in the rat thalamus. J Comp Neurol. 2001;429:372–387. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010115)429:3<372::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberman AD, Feller MB, Chapman B. Mechanisms underlying development of visual maps and receptive fields. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:479–509. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar S, Qi HX, Jain N, Kaas JH. Cortical and thalamic connections of the representations of the teeth and tongue in somatosensory cortex of new world monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 2007;501:95–120. doi: 10.1002/cne.21232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain N, Florence SL, Kaas JH. Reorganization of somatosensory cortex after nerve and spinal cord injury. News Physiol Sci. 1998;13:143–149. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1998.13.3.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JI. Comparative development of somatic sensory cortex. In: Jones EG, Peters A, editors. Cerebral cortex. 8B. New York: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 335–449. [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG, editor. The thalamus. 2. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG, Wise SP, Coulter JD. Differential thalamic relationships of sensory-motor and parietal cortical fields in monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1979;183:833–881. doi: 10.1002/cne.901830410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG, Friedman DP, Hendry SH. Thalamic basis of place- and modality-specific columns in monkey somatosensory cortex: a correlative anatomical and physiological study. J Neurophysiol. 1982;48:545–568. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.2.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano SL, Whitsel BL, Hand PJ. Patterns of ventrobasal thalamic activity evoked by controlled somatic stimuli: a preliminary analysis. In: Macchi G, Rustioni A, Spreafico R, editors. Somatosensory integration in the thalamus Amsterdam: Elsevier. 1983:107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. The somatosensory thalamus and associated pathways. In: Basebaum AI, Kaneko A, Shepherd GM, Westheimer G, Gardner E, Kaas JH, editors. The senses: a comprehensive reference. Vol. 6. San Diego: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 117–141. (Somatosensation). [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Catania KC. How do features of sensory representations develop? Bioessays. 2002;24:334–343. doi: 10.1002/bies.10076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Guillery RW, Allman JM. Discontinuities in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus corresponding to the optic disc: a comparative study. J Comp Neurol. 1973;147:163–179. doi: 10.1002/cne.901470203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Nelson RJ, Sur M, Dykes RW, Merzenich MM. The somatotopic organization of the ventroposterior thalamus of the squirrel monkey, Saimiri sciureus. J Comp Neurol. 1984;226:111–140. doi: 10.1002/cne.902260109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Fujiyama F. Complementary distribution of vesicular glutamate transporters in the central nervous system. Neurosci Res. 2002;42:243–250. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LC, Shatz CJ. Synaptic activity and the construction of cortical circuits. Science. 1996;274:1133–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killackey HP. Pattern formation in the trigeminal system of the rat. Trends Neurosci. 1980;3:303–305. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurti A, Kanagasuntheram R, Wong WC. Functional significance of the fibrous laminae in the ventrobasal complex of the thalamus of slow loris. J Comp Neurol. 1972;145:515–523. doi: 10.1002/cne.901450404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krubitzer LA, Kaas JH. The somatosensory thalamus of monkeys: cortical connections and a redefinition of nuclei in marmosets. J Comp Neurol. 1992;319:123–140. doi: 10.1002/cne.903190111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liguz-Lecznar M, Skangiel-Kramska J. Vesicular glutamate transporters (VGLUTs): the three musketeers of glutamatergic system. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2007;67:207–218. doi: 10.55782/ane-2007-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CS, Merzenich MM, Sur M, Kaas JH. Connections of areas 3b and 1 of the parietal somatosensory strip with the ventroposterior nucleus in the owl monkey (Aotus trivirgatus) J Comp Neurol. 1979;185:355–371. doi: 10.1002/cne.901850209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loe PR, Whitsel BL, Dreyer DA, Metz CB. Body representation in ventrobasal thalamus of macaque: a single-unit analysis. J Neurophysiol. 1977;40:1339–1355. doi: 10.1152/jn.1977.40.6.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayner L, Kaas JH. Thalamic projections from electrophysiologically defined sites of body surface representations in areas 3b and 1 of somatosensory cortex of Cebus monkeys. Somatosens Res. 1986;4:13–29. doi: 10.3109/07367228609144595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountcastle VB, Henneman E. The representation of tactile sensibility in the thalamus of the monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1952;97:409–439. doi: 10.1002/cne.900970302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahmani M, Erisir A. VGluT2 immunochemistry identifies thalamocortical terminals in layer 4 of adult and developing visual cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2005;484:458–473. doi: 10.1002/cne.20505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson RJ, Kaas JH. Connections of the ventroposterior nucleus of the thalamus with the body surface representations in cortical areas 3b and 1 of the cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis) J Comp Neurol. 1981;199:29–64. doi: 10.1002/cne.901990104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padberg J, Cerkevich C, Engle J, Rajan AT, Recanzone G, Kaas J, Krubitzer L. Thalamocortical connections of parietal somatosensory cortical fields in macaque monkeys are highly divergent and convergent. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:2038–2064. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JC, Haines DE. Somatosensory thalamus of a prosimian primate (Galago senegalensis). II. An HRP and Golgi study of the ventral posterolateral nucleus (VPL) J Comp Neurol. 1980;190:559–580. doi: 10.1002/cne.901900310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poggio GF, Mountcastle VB. The functional properties of ventrobasal thalamic neurons studied in unanesthetized monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 1963;26:775–806. doi: 10.1152/jn.1963.26.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons TP, Wall JT, Garraghty PE, Cusick CG, Kaas JH. Consistent features of the representation of the hand in area 3b of macaque monkeys. Somatosens Res. 1987;4:309–331. doi: 10.3109/07367228709144612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pubols LM. Somatic sensory representation in thalamic ventrobasal complex of the spider monkey (Ateles) Brain Behav Evol. 1968;1:305–323. [Google Scholar]

- Qi HX, Kaas JH. Myelin stains reveal an anatomical framework for the representation of the digits in somatosensory area 3b of macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 2004;477:172–187. doi: 10.1002/cne.20247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi HX, Kaas JH. Organization of primary afferent projections to the gracile nucleus of the dorsal column system of primates. J Comp Neurol. 2006;499:183–217. doi: 10.1002/cne.21061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi HX, Lyon DC, Kaas JH. Cortical and thalamic connections of the parietal ventral somatosensory area in marmoset monkeys (Callithrix jacchus) J Comp Neurol. 2002;443:168–182. doi: 10.1002/cne.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausell E, Jones EG. Chemically distinct compartments of the thalamic VPM nucleus in monkeys relay principal and spinal trigeminal pathways to different layers of the somatosensory cortex. J Neurosci. 1991;11:226–237. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-01-00226.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausell E, Bae CS, Vinuela A, Huntley GW, Jones EG. Calbindin and parvalbumin cells in monkey VPL thalamic nucleus: distribution, laminar cortical projections, and relations to spinothalamic terminations. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4088–4111. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-04088.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausell E, Bickford L, Manger PR, Woods TM, Jones EG. Extensive divergence and convergence in the thalamocortical projection to monkey somatosensory cortex. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4216–4232. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-11-04216.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JL, Pouget P, Qi HX, Zhou Z, Bernard MR, Burish MJ, Haitas J, Bonds AB, Kaas JH. Widespread spatial integration in primary somatosensory cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10233–10237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803800105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatz CJ. Impulse activity and the patterning of connections during CNS development. Neuron. 1990;5:745–756. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90333-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sur M, Merzenich MM, Kaas JH. Magnification, receptive-field area, and “hypercolumn” size in areas 3b and 1 of somatosensory cortex in owl monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 1980;44:295–311. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.44.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sur M, Nelson RJ, Kaas JH. Representations of the body surface in cortical areas 3b and 1 of squirrel monkeys: comparisons with other primates. J Comp Neurol. 1982;211:177–192. doi: 10.1002/cne.902110207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brederode JF, Mulligan KA, Hendrickson AE. Calcium-binding proteins as markers for subpopulations of GABAergic neurons in monkey striate cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1990;298:1–22. doi: 10.1002/cne.902980102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Loos H. Barreloids in mouse somatosensory thalamus. Neurosci Lett. 1976;2:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(76)90036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Loos H, Dörfl J. Does the skin tell the somatosensory cortex how to construct a map of the periphery? Neurosci Lett. 1978;7:23–30. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(78)90107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker WI. Principles of organization of the ventrobasal complex in mammals. Brain Behav Evol. 1973;7:253–336. doi: 10.1159/000124417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker WI, Johnson JI., Jr Correlation between nuclear morphology and somatotopic organization in ventro-basal complex of the raccoon’s thalamus. J Anat. 1965;99(Pt 4):761–790. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welker WI, Johnson JI, Jr, Pubols BH., Jr Some morphological and physiological characteristics of the somatic sensory system in raccoons. Am Zool. 1964;4(Pt 4):75–94. doi: 10.1093/icb/4.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener SI, Johnson JI, Ostapoff EM. Demarcations of the mechanosensory projection zones in the raccoon thalamus, shown by cytochrome oxidase, acetylcholinesterase, and Nissl stains. J Comp Neurol. 1987;258:509–526. doi: 10.1002/cne.902580404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson P, Kitchener PD, Snow PJ. Cutaneous receptive field organization in the ventral posterior nucleus of the thalamus in the common marmoset. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:1865–1875. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.4.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Kaas JH. Architectonic subdivisions of neocortex in the gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2008;291:1301–1333. doi: 10.1002/ar.20758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Kaas JH. Architectonic subdivisions of neocortex in the tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri) Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2009a;292:994–1027. doi: 10.1002/ar.20916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Kaas JH. An architectonic study of the neocortex of the short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis domestica) Brain Behav Evol. 2009b;73:206–228. doi: 10.1159/000225381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Kaas JH. Architectonic subdivisions of neocortex in the Galago (Otolemur garnetti) Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2010;293:1033–1069. doi: 10.1002/ar.21109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Gharbawie OA, Luethke LE, Kaas JH. Thalamic connections of architectonic subdivisions of temporal cortex in grey squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) J Comp Neurol. 2008;510:440–461. doi: 10.1002/cne.21805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Riley M. Changes in the visual system of monocularly sutured or enucleated cats demonstrable with cytochrome oxidase histochemistry. Brain Res. 1979;171:11–28. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90728-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolsey TA, Welker C, Schwartz RH. Comparative anatomical studies of the SmI face cortex with special reference to the occurrence of “barrels” in layer IV. J Comp Neurol. 1975;164:79–94. doi: 10.1002/cne.901640107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CW, Kaas JH. Somatosensory cortex of prosimian Galagos: physiological recording, cytoarchitecture, and corticocortical connections of anterior parietal cortex and cortex of the lateral sulcus. J Comp Neurol. 2003;457:263–292. doi: 10.1002/cne.10542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zantua JB, Wasserstrom SP, Arends JJ, Jacquin MF, Woolsey TA. Postnatal development of mouse “whisker” thalamus: ventroposterior medial nucleus (VPM), barreloids, and their thalamocortical relay neurons. Somatosens Mot Res. 1996;13:307–322. doi: 10.3109/08990229609052585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]