Abstract

Introduction

The effect of socioeconomic status (SES) on stroke mortality at population level has been controversial. This study explores the association of SES in childhood and adulthood with stroke mortality, as well as variations in this association among countries/regions.

Methods

Sex-specific stroke mortality at country level with death registry covering ≥ 70% population was obtained from the World Health Organization. Human Development Index (HDI) developed by the United Nations was chosen as the SES indicator. The associations between the latest available stroke mortality with HDI in 1999 (adulthood SES) and with HDI in 1960 (childhood SES) for the group aged 45–54 years among countries were examined with regression analysis. Age-standardized stroke mortality and HDI during 1974–2001 were used to estimate the association by time point.

Results

The population data were available mostly for low-middle to high income countries. HDI in 1960 and 1999 were both inversely associated with stroke mortality in the group aged 45–54 years in 39 countries/regions. HDI in 1960 accounted for 37% of variance of stroke mortality among countries/regions; HDI in 1999 for 35% in men and 53% in women (P < 0.001). There was a quadratic relationship between age-standardized stroke mortality and HDI for the countries from 1974 to 2001: the association was positive when HDI < 0.77 but it became negative when HDI > 0.80.

Conclusions

SES is a strong predictor of stroke mortality at country level. Stroke mortality increased with improvement of SES in less developed countries/region, while it decreased with advancing SES in more developed areas.

Keywords: Socioeconomic status, Stroke, Mortality

Introduction

Stroke causes 5.5 million deaths and the loss of 49 million disability-adjusted life years worldwide each year [1]. It has been estimated that by the year 2020 stroke will remain the second leading cause of death, and in terms of disability it will be among the five most important causes of disability worldwide [2].

It has been suggested that stroke burden and time trend of stroke varied among populations [3,4], but trends in common risk factors may not fully explain time or inter-population variations in stroke occurrence [5-10]. According to Global Health Statistics in 1996, the higher stroke mortality rates for men aged 45–59 years were observed in Formerly Socialist Economies of Europe (FSE, 135.5/100,000), China (CHN, 134.3), Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC, 104.1). The lower rates were reported from countries with Established Market Economies (EME, 36.9, such as USA, Canada, Japan and Australia); Middle Eastern Crescent (MEC, 73.2) and Other Asia and Islands (OAI, 85.7). In women, the higher rates were observed in CHN (110.5), LAC (83.9) and FSE (83.1). The lower rates were in EME (22.7), MEC (65.5) and OAI (67.2) [3]. Sarti and Rastenyte presented trends of stroke mortality during 1968–1994 [4]. The most developed countries experienced remarkably declining trends about 20 years, but less developed countries like eastern European countries experienced increasing trends for stroke mortality during the same period. Recent studies on life course exposures demonstrated that children exposed to low socioeconomic status (SES) were at high risk of stroke at adulthood [11-13]. The findings from adult population studies examining the relationship between SES and the risk of stroke are conflicting, with some reporting positive and some negative associations [14-17]. The effect of population SES on stroke mortality at country level has not been addressed. We carried out an ecological study to explore the association between SES in childhood and in adulthood with stroke mortality among countries/regions, to help define populations at a higher risk and predict the trends of stroke mortality for health policy.

Methodology

Data sources

The inclusion criteria for countries/regions included in our study were the estimated coverage of all deaths reported in the routine mortality statistics for countries/regions ≥ 70% [18], and availability of data on stroke mortality and SES indicator. The data included deaths for broad stroke categories registered in national vital registration systems, with underlying cause of death as coded by the relevant national authority (ICD 8–9 code: 430–438 and ICD 10 code: I60-69).

Infant mortality rates and children under 5 mortality rates are widely used as measures of social development [19,20], while Gross Domestic Product (GDP)/capita most directly measures material circumstances, the Human Development Index (HDI) is a complex index of socioeconomic status at population level [21-23], they were all compared in the current study.

The HDI is an index combining normalized measures of life expectancy, literacy, educational attainment, and GDP per capita at country level [22]. The index, the development of which had been influenced by the ideas of Indian Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen, has been used since 1990 by the United Nations in its annual Human Development Report [22]. The HDI combines three basic dimensions:

● Life expectancy at birth, as an index of population health and longevity.

● Knowledge and education, as measured by the adult literacy rate (with two-thirds weighting) and the combined primary, secondary, and tertiary gross enrollment ratio (with one-third weighting).

● Standard of living, as measured by the natural logarithm of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita at purchasing power parity (PPP) in United States dollars.

Performance in each dimension is expressed as a value between 0 and 1, the higher the number, the better the result. Therefore, HDI might be expected to indicate socioeconomic development more comprehensively.

The above-mentioned indicators were used to explore the associations between SES and stroke mortality at population level based on the availability of the data, and the optimal one was selected to indicate SES in this study.

The earliest available and accessible SES indicator was in 1960. Populations in childhood in 1960 and dying of stroke in their adulthood most likely happened over their 35 years old. But mortality rate from stroke in the age group of 35-44 years was very low therefore fluctuated significantly from year to year. Mortality rate for the age group of 45–54 years old was used to analyze the association between stroke mortality and SES in childhood and adulthood. Sex-specific stroke mortality rates (per 100,000 per year) for the age group of 45–54 years in the latest available 3 years (1997–2003) were averaged using data derived from the World Health Organization (WHO) [6]. In the present study, SES in childhood was represented by HDI in 1960, infant mortality rate in 1960, under-5 mortality rate in 1960 and GDP/capita in 1970, which were all the earliest available and accessible data. Since the latest available data for stroke mortality ranged between 1997 and 2003, and SES indicators in adulthood were obtained in 1999 or 2000 for most of the countries/regions, SES in adulthood was represented by HDI in 1999, GDP/capita in 1999, infant mortality rate in 2000 and under-5 mortality rate in 2000.

In order to minimize confounding effects, we used the data on systolic blood pressure, prevalence of smoking and obese, alcohol and saturated fat consumption as controlling variables in this analysis. Data for adult mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) in 2002, prevalence of obese (OB) in the latest available year (1995–2003), per capita alcohol consumption (> 15 years) (in litres of pure alcohol) in 2000–2001 (ALC), were obtained from WHO data sources [6,7,24,25].

Countries/regions with data available on stroke mortality (1974–1976, 1979–1981, 1984–1986, 1989–1991, 1994–1996 and 1999–2001) and HDI (1975, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1995 and 2000) calculated through the same method were used to analyze the effect of socioeconomic development on stroke mortality. Sex-specific stroke mortality rates (per 100,000 per year) in eight age classes, 35–39 years, 40–44 years, 45–49 years, 50–54 years, 55–59 years, 60–64 years, 65–69 years and 70–74 years from 1975 to 2000 for the countries/regions meeting the inclusion criteria were derived from WHO [6]. The sex-specific stroke mortality rate in 5 year age group (35–74 years) were smoothed over 5 years at each of six time periods, and then standardized to 35–74 years according to the world standard population (1996), respectively [26]. The age range 35–74 years was used, because death from stroke rarely occurs in people younger than 35, and diagnostic accuracy on death certificates for stroke may be less reliable for people older than 74 years [27].

Statistical analysis

Since the mortality data did not follow a normal distribution, they were transformed by natural logarithm prior to analysis.

Pearson correlation analysis was made between stroke mortality and childhood SES indicators (HDI in 1960, infant mortality in 1960, under-5 mortality in 1960 and GDP/capita in 1970), and between stroke mortality and adulthood SES indicators (HDI in 1999, GDP/capita in 1999, infant mortality in 2000 and under-5 mortality in 2000), as well as between childhood or adulthood SES indicators.

Linear regression models were constructed with stroke mortality as dependent variable, and SES indicators in childhood and adulthood as respective independent variables. The choice of SES indicators was identified by comparing the sum of ranks of correlation coefficients between each childhood or adulthood indicator and stroke mortality, and the higher the correlation coefficient, the lower the rank.

Linear regression models were constructed with stroke mortality as the dependent variable, and HDI in 1960 and HDI in 1999 as independent variables. Multiple regression models were constructed with stroke mortality as the dependent variable, and HDI in 1960 and HDI in 1999 as independent variables plus confounding variables. Since the sample size was not large enough, confounding variables were adjusted one by one separately.

Curve estimation was used to explore the association between HDI and stroke mortality when each country/region at each of six time periods was regarded as one study unit and considered simultaneously. X axis represents HDI for each country/region at each of six time periods, and Y axis represents the corresponding stroke mortality. The quadratic model identified had better goodness-of-fit (larger R square) than linear, logarithmic, inverse, cubic, compound, power, S, growth, exponential and logistic models in this study, therefore, only the results of quadratic model were showed.

The significance level was put at P < 0.05 (2-tailed). SPSS software (version 16.0, copyright SPSS Inc. in USA) was used for the statistical analysis.

The HDI in 1980, 1985, 1990 and 1995 were also used to explore the association of stroke mortality in the latest available year with the SES indicator.

Results

Countries/regions with the HDI and some confounding factors used in the analysis lists in Table 1. The status of socioeconomic development among the 39 countries/regions ranged from HDI as low as 0.70 in Slovakia to HDI as high as 0.939 in Norway in 1999. Many countries/regions had no nationwide survey data of prevalence of hypertension or obesity. Stroke mortality rate was high in Mauritius (98.5 in men and 56.1in women) and low in Switzerland (7.7 per 100,000 in men and 7.5 in women) in recent years.

Table 1.

The Human Development Index (HDI) in 1999 and the distribution of some available confounding factors for the countries/regions involved in the study

| Country/region* |

Stroke mortality (1/100,000), 45–54 yrs |

HDI 1999 |

SBP |

HPT (%) |

SMK (%) |

SF** | ALC** |

OB (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | ||||

|

South America | |||||||||||||

| ARG |

59.83 |

34.30 |

0.842 |

120 |

119 |

.. |

.. |

46.8 |

34.0 |

4.45 |

8.55 |

.. |

.. |

| BRA |

66.00 |

49.37 |

0.750 |

124 |

119 |

.. |

.. |

38.2 |

29.3 |

3.10 |

5.30 |

8.9 |

13.1 |

| CHL |

30.37 |

25.13 |

0.825 |

119 |

116 |

.. |

.. |

26.0 |

18.3 |

2.41 |

6.02 |

19.0 |

25.0 |

| COL |

30.23 |

31.40 |

0.765 |

122 |

119 |

.. |

.. |

22.3 |

23.5 |

6.62 |

5.90 |

.. |

.. |

| CRI |

15.20 |

17.60 |

0.821 |

122 |

117 |

.. |

.. |

28.6 |

6.6 |

8.85 |

5.50 |

.. |

.. |

| ECU |

28.87 |

23.73 |

0.726 |

124 |

122 |

.. |

.. |

45.5 |

17.4 |

17.63 |

2.00 |

.. |

.. |

| SLV |

20.13 |

15.30 |

0.701 |

.. |

|

.. |

.. |

38.0 |

12.0 |

3.98 |

3.50 |

.. |

.. |

| MEX |

23.47 |

20.20 |

0.790 |

125 |

121 |

38.6 |

30.1 |

51.2 |

18.4 |

4.60 |

4.62 |

18.6 |

28.1 |

| PAN |

24.37 |

17.63 |

0.784 |

.. |

|

.. |

|

56.0 |

20.0 |

6.55 |

6.00 |

.. |

.. |

| PRY |

40.10 |

50.37 |

0.738 |

122 |

128 |

32.4 |

41.9 |

24.1 |

5.5 |

5.81 |

6.70 |

.. |

.. |

| VEN |

40.93 |

34.30 |

0.765 |

120 |

117 |

47.7 |

32.2 |

41.8 |

39.2 |

4.35 |

8.80 |

.. |

.. |

| URY |

45.63 |

37.67 |

0.828 |

.. |

|

.. |

|

31.7 |

14.3 |

3.04 |

7.00 |

17.0 |

19.0 |

|

Mean |

35.43 |

29.75 |

0.778 |

122 |

120 |

39.6 |

34.7 |

37.5 |

19.9 |

5.95 |

5.82 |

15.9 |

21.3 |

|

Asia | |||||||||||||

| HKG |

20.37 |

11.50 |

0.880 |

130 |

123 |

.. |

.. |

27.1 |

2.9 |

.. |

.. |

.. |

.. |

| ISR |

10.23 |

7.13 |

0.893 |

128 |

121 |

.. |

.. |

33.0 |

24.0 |

8.87 |

2.00 |

19.8 |

25.4 |

| KOR |

53.83 |

26.23 |

0.875 |

126 |

121 |

21.8 |

19.4 |

65.1 |

4.8 |

5.88 |

7.70 |

1.7 |

3.0 |

| JPN |

36.87 |

18.07 |

0.928 |

127 |

119 |

42.7 |

35.0 |

52.8 |

13.4 |

2.83 |

7.38 |

.. |

… |

| SGP |

20.57 |

12.03 |

0.876 |

124 |

119 |

.. |

.. |

26.9 |

3.1 |

.. |

2.73 |

5.3 |

6.7 |

|

Mean |

28.37 |

14.99 |

0.890 |

127 |

121 |

32.3 |

27.2 |

41.0 |

9.6 |

5.86 |

4.95 |

8.9 |

11.7 |

|

Africa | |||||||||||||

| MUS |

98.53 |

56.07 |

0.765 |

127 |

124 |

.. |

.. |

44.8 |

2.9 |

3.51 |

3.20 |

8.0 |

20.0 |

|

Europe |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AUT |

17.10 |

13.10 |

0.921 |

129 |

122 |

.. |

.. |

30.0 |

19.0 |

19.49 |

12.58 |

.. |

.. |

| BEL |

18.13 |

13.40 |

0.935 |

127 |

119 |

.. |

.. |

30.0 |

26.0 |

34.16 |

10.06 |

10.3 |

11.0 |

| DEN |

21.90 |

11.90 |

0.921 |

122 |

115 |

.. |

.. |

32.0 |

29.0 |

22.59 |

11.93 |

.. |

.. |

| FIN |

25.63 |

16.63 |

0.925 |

131 |

125 |

.. |

.. |

27.0 |

20.0 |

12.86 |

10.43 |

20.8 |

23.9 |

| FRA |

15.93 |

8.13 |

0.924 |

129 |

125 |

.. |

.. |

38.6 |

30.3 |

19.79 |

13.54 |

.. |

.. |

| DEU |

15.43 |

10.67 |

0.921 |

134 |

130 |

55.4 |

56.6 |

39.0 |

31.0 |

24.68 |

12.90 |

13.6 |

12.3 |

| GRC |

26.10 |

14.43 |

0.881 |

131 |

124 |

18.5 |

15.9 |

47.0 |

29.0 |

3.57 |

9.30 |

.. |

.. |

| HUN |

66.67 |

29.10 |

0.829 |

134 |

126 |

86.2 |

.. |

44.0 |

27.0 |

24.03 |

11.92 |

18.4 |

20.4 |

| IRL |

16.70 |

14.70 |

0.913 |

.. |

|

.. |

.. |

32.0 |

31.0 |

17.58 |

14.50 |

14.0 |

12.0 |

| ITA |

15.27 |

9.97 |

0.909 |

129 |

122 |

42.0 |

43.3 |

32.4 |

17.3 |

12.96 |

9.14 |

.. |

… |

| NLD |

14.47 |

15.83 |

0.931 |

131 |

122 |

.. |

.. |

37.0 |

29.0 |

14.68 |

9.74 |

10.2 |

11.9 |

| NOR |

13.67 |

9.60 |

0.939 |

.. |

|

.. |

.. |

31.0 |

32.0 |

17.34 |

5.80 |

6.8 |

5.8 |

| PRT |

38.73 |

20.57 |

0.874 |

127 |

124 |

.. |

.. |

30.2 |

7.1 |

15.70 |

12.49 |

.. |

.. |

| ESP |

17.20 |

9.23 |

0.908 |

123 |

118 |

41.7 |

39.0 |

42.1 |

24.7 |

5.42 |

12.25 |

12.3 |

12.1 |

| SWE |

15.70 |

11.37 |

0.936 |

131 |

125 |

39.6 |

40.9 |

19.0 |

19.0 |

18.39 |

6.90 |

10.4 |

9.5 |

| CHE |

7.70 |

7.53 |

0.924 |

126 |

115 |

.. |

.. |

39.0 |

28.0 |

12.57 |

11.53 |

7.9 |

7.5 |

| GBR |

17.93 |

15.20 |

0.923 |

132 |

127 |

34.7 |

25.7 |

27.0 |

26.0 |

8.70 |

10.39 |

.. |

.. |

|

Mean |

21.43 |

13.61 |

0.913 |

129 |

123 |

45.4 |

36.9 |

34.0 |

25.0 |

16.74 |

10.91 |

12.5 |

12.6 |

|

USA,CAN,AUS &NZL | |||||||||||||

| USA |

17.70 |

14.37 |

0.934 |

123 |

119 |

21.0 |

19.7 |

25.7 |

21.5 |

6.37 |

8.51 |

25.8 |

|

| CAN |

9.93 |

8.93 |

0.936 |

126 |

118 |

23.5 |

15.6 |

27.0 |

23.0 |

16.37 |

8.26 |

15.9 |

31.8 |

| AUS |

9.57 |

7.77 |

0.936 |

118 |

125 |

30.8 |

20.1 |

21.1 |

18.0 |

12.75 |

9.19 |

14.8 |

13.9 |

| NZL |

14.27 |

14.03 |

0.913 |

134 |

123 |

.. |

.. |

25.0 |

25.0 |

14.17 |

9.80 |

21.9 |

15.3 |

| Mean | 12.87 | 11.28 | 0.930 | 125 | 121 | 25.1 | 18.5 | 25.0 | 22.0 | 12.42 | 8.94 | 19.6 | 23.2 |

*ARG Argentina, AUS Australia, AUT Austria, BEL Belgium, BRA Brazil, CAN Canada, CHE, Switzerland, CHL, Chile; COL, Colombia; CRI, Costa Rica, DEU, Germany; DNK Denmark; ECU Ecuador, ESP Spain, FIN Finland, FRA France, GRC Greece, GBR United Kingdom, HKG Hong Kong, HRV Costa Rica, HUN Hungary, IRL Ireland, ITA Italy, ISR Israel, JPN Japan, KOR Korea, Rep. of; MUS Mauritius, MEX Mexico, NLD Netherlands, NOR Norway, NZL New Zealand, PAN Panama PRT Portugal, PRY Paraguay, SGP Singapore SLV El Salvador, SWE Sweden, USA United States of America, VEN Venezuela, URY Uruguay.

OB Adults (≥15 years) who are obese (%) in the latest available year.

SBP Mean adult SBP (mmHg) in 2002.

HPT The latest available hypertension prevalence.

SMK The latest available adult smoking prevalence.

SF Saturated fat (/capita/year (kg)) in 1999.

ALC Per capita alcohol consumption (>15 years) (in litres of pure alcohol) in 2000–2001.

** Data available irrespective of men and women.

Pearson correlation analysis among SES indicators in childhood and adulthood shows that the indicators were correlated each other (Table 2). The choice of SES indicators was determined by comparing sum of ranks of correlation coefficients between each indicator and stroke mortality (Table 3). The correlation coefficients and the rank of the correlations were very close for GDP/capita (slightly higher in childhood) and HDI (slightly higher in adulthood) for both 1960 and 1999. HDI was chosen because it was a more comprehensive indicator of socioeconomic development status. HDI consisted of not only economic productivity but also life-expectancy, health care services and education levels. Those factors are largely related to the susceptibility to development of stroke and efficiency in primary and secondary prevention of stroke in the populations.

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients between socioeconomic status indicators in childhood and adulthood

| SES indicators | GDP/capita in 1970 | Infant mortality in 1960^ | Under-5 mortality in 1960^^ |

|---|---|---|---|

|

HDI in 1960 |

r = 0.860 |

r = −0.871 |

r = −0.875 |

|

P = 0.000 |

P = 0.000 |

P = 0.000 |

|

|

GDP/capita in 1970 |

|

r = −0.684 |

r = −0.680 |

|

P = 0.000 |

P = 0.000 |

||

|

Infant mortality in 1960^ |

|

|

r = 0.990 |

|

P = 0.000 | |||

| |

HDI in 1999 |

Infant mortality in 2000* |

Under-5 mortality in 2000** |

|

GDP/capita in 1999 |

r = 0.876 |

r = −0.139 |

r = −0.731 |

|

P = 0.000 |

P = 0.411 |

P = 0.000 |

|

|

HDI in 1999 |

|

r = −0.131 |

r = −0.922 |

|

P = 0.440 |

P = 0.000 |

||

|

Infant mortality in 2000* |

|

|

r = 0.728 |

| P = 0.000 |

CC correlation coefficient.

P significance.

^ Infant mortality in 1960 (per 1,000 live births).

^^ Under-5 mortality in 1960 (per 1,000).

* Infant mortality rate (per 1,000 live births).

** Under-5 mortality rate (per 1,000).

Table 3.

The sum of rank of correlation coefficients between childhood ses indicators and stroke mortality in men and women aged 45–54 years

| SES indicators |

Stroke mortality^ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Men |

Women |

Sum of rank | |||

| CC | Rank | CC | Rank | ||

|

HDI in 1960 |

−0.612* |

2 |

−0.608* |

2 |

4 |

|

GDP/capita in 1970 |

−0.623* |

1 |

−0.620* |

1 |

2 |

| Infant mortality in 1960^^ |

0.517* |

3 |

0.585* |

3 |

6 |

| Under-5 mortality in 1960^^^ |

0.490* |

4 |

0.575* |

4 |

8 |

|

GDP/capita in 1999 |

−0.594* |

1 |

−0.700* |

2 |

3 |

|

HDI in 1999 |

−0.594* |

1 |

−0.727* |

1 |

2 |

| Infant mortality in 2000^^ |

0.174 |

4 |

0.053 |

4 |

8 |

| Under-5 mortality in 2000^^^ | 0.381* | 3 | 0.587* | 3 | 6 |

SES socioeconomic status.

CC correlation coefficient.

^ Per 100,000 per year (Ln).

* P < 0.05.

^^ Infant mortality (per 100,000).

^^^ Under-5 mortality (per 1,000) in 1960.

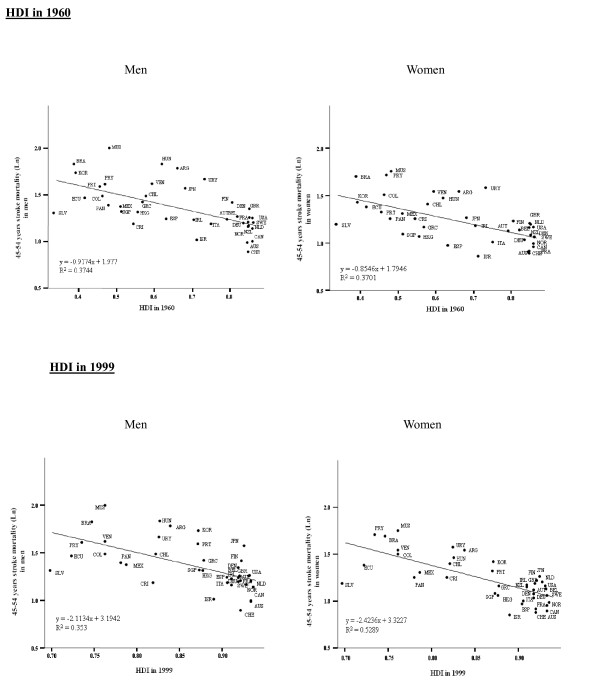

Table 4 and Figure 1 show that both HDI in 1960 and HDI in 1999 were inversely associated with stroke mortality in men and women. HDI in 1960 explained 37% of variance of stroke mortality among countries/regions in men and women (P < 0.001). HDI in 1999 explained 35% in men and 53% in women (P < 0.001), respectively. Table 4 shows that HDI in 1960 and HDI in 1999 was still significantly and negatively correlated with stroke mortality in men and women, respectively after adjusting for each confounding variable.

Table 4.

Regression analysis of log-stroke mortality in the latest available three years in the group aged 45–54 years with HDI in 1960 and HDI in 1999 (Unadjusted and Adjusted Models)

| HDI and confounding variables |

Stroke mortality* (men) |

Stroke mortality* (women) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RC | P | AdjustedR2 | RC | P | AdjustedR2 | |

|

Unadjusted model HDI in 1960 |

−0.917 |

0.000 |

0.357 |

−0.855 |

0.000 |

0.353 |

|

Adjusted models** HDI in 1960+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SBP |

−1.147 |

0.000 |

0.446 |

−1.023 |

0.000 |

0.444 |

| HPT |

−1.163 |

0.000 |

0.629 |

−1.039 |

0.005 |

0.443 |

| SMK |

−0.784 |

0.001 |

0.380 |

−0.945 |

0.000 |

0.349 |

| Obese |

−1.440 |

0.000 |

0.518 |

−1.057 |

0.001 |

0.439 |

| ALC |

−1.071 |

0.000 |

0.370 |

−0.906 |

0.000 |

0.360 |

| SF |

−0.910 |

0.001 |

0.367 |

−0.807 |

0.001 |

0.411 |

|

Unadjusted model HDI in 1999 |

−2.113 |

0.001 |

0.336 |

−2.424 |

0.000 |

0.516 |

|

Adjusted models** HDI in 1999+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SBP |

−2.794 |

0.000 |

0.412 |

−2.945 |

0.000 |

0.640 |

| HPT |

−2.190 |

0.017 |

0.314 |

−2.964 |

0.000 |

0.670 |

| SMK |

−1.831 |

0.000 |

0.400 |

−2.411 |

0.000 |

0.503 |

| Obese |

−4.018 |

0.000 |

0.625 |

−3.623 |

0.000 |

0.663 |

| ALC |

−2.561 |

0.000 |

0.348 |

−2.765 |

0.000 |

0.527 |

| SF | −1.912 | 0.002 | 0.325 | −2.203 | 0.000 | 0.519 |

RC regression coefficient.

SBP mean adult SBP in 2002.

OB adults (≥ 15 years) who are obese (%) in the latest available year.

HPT the latest available hypertension prevalence.

SMK the latest available adult smoking prevalence.

SF saturated fat (/capita/year (kg)) intake in 1999.

ALC per capita alcohol consumption (> 15 years) (in litres of pure alcohol) in 2000–2001.

* Per 100,000 per year (Ln).

** Adjusted model: each adjustment only adjusted for one confounding variable.

Figure 1.

Linear regression between stroke mortality (per 100,000 per year)in the latest available three years and HDI in 1960 and HDI in 1999 in the group aged 45–54 years. Abbreviations: ARG Argentina, AUS Australia, AUT Austria BEL Belgium BRA Brazil, CAN Canada, CHE Switzerland, CHL Chile, COL Colombia, CRI Costa Rica, DEU Germany, DNK Denmark, ECU Ecuador, ESP Spain, FIN Finland, FRA France, GRC Greece, GBR United Kingdom, HKG Hong Kong, HRV Costa Rica, HUN Hungary, IRL Ireland, ITA Italy, ISR Israel, JPN Japan, KOR Korea, Rep. of; MUS Mauritius, MEX Mexico, NLD Netherlands, NOR Norway, NZL New Zealand; PAN Panama, PRT Portugal, PRY Paraguay, SGP Singapore, SLV El Salvador, SWE Sweden, USA United States of America, VEN Venezuela, URY Uruguay.

Stroke mortality in the countries/regions at the bottom tertile of HDI both in 1960 and 1999 was 2.52 and 2.61 times higher than those at the top tertile of HDI in both periods in men (38.5 per 100,000 per year, 95% CI: 15.5-61.6 vs. 14.8, 10.9-18.7), and women (28.8, 14.2-43.4 vs. 11.4, 8.5-14.4) separately.

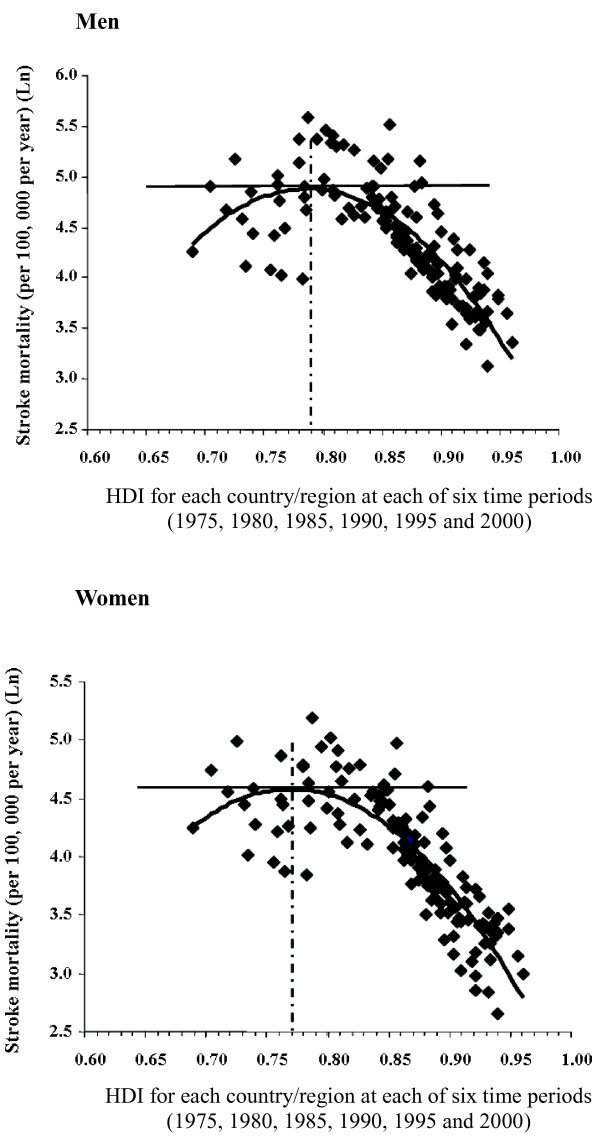

Figure 2 illustrates that the peak of age-standardized stroke mortality was exhibited at about HDI = 0.77-0.81 for men and 0.75-0.79 for women (P < 0.01). Stroke mortality increased with improvement of HDI if HDI < 0.81 for men and HDI < 0.79 for women, while stroke mortality decreased with increasing HDI if HDI > 0.77 for men and HDI > 0.75 for women during 1974–2001 when each country/region at each of six time periods was considered simultaneously. The strength of the association was stronger as the year of the SES indicatorbecame closer to the year of mortality data used (see Additional file 1: Table S1).

Figure 2.

Curve fit for age-standardized stroke mortality (35-74 years)and HDI when each. Country/region at each time period as one study unit.

Discussion

This ecological study quantitatively estimated the effect of SES on stroke mortality at population level. HDI was used as a SES indicator in this study due to its significant association with stroke mortality and more comprehensively represented the social and economic development status at country level. In general, both childhood SES (HDI in 1960) and adulthood SES (HDI in 1999) were inversely associated with stroke mortality in recent years for men and women in middle- or high-income countries/regions. The direction of the association between SES and stroke mortality was opposite for low and high HDI levels: the association was positive for the countries/regions at low HDI level, but it was negative for the countries/regions at high HDI level (p < 0.01 for both directions).

Our finding that the risk of stroke is associated with low SES in childhood at population level suggests that exposure to socioeconomic deprivation in early life might increase the risk of stroke in adulthood. Possible pathophysiological mechanisms may include underlying lasting changes in vascular structure in response to under-nutrition in early life, activation of the renin-angiotensin system predisposing to the development of hypertension [28,29], impact on hormonal and metabolic programming resulting in insulin resistance and diabetes [30,31], adverse lipid and thrombogenic profiles [32,33] predisposing to atherogenesis [11,34].

A quadratic relationship revealed that the risk of stroke increased with improvement of SES in regions at a lower stage of socioeconomic development, while it decreased with increasing SES in regions at a higher stage of socioeconomic development. This finding likely reflected the changing pattern lifestyle, health literacy and access to health services through different stages of socioeconomic development. High blood pressure, obesity and hyperlipidemia are risk factors for stroke that are related to an unhealthy lifestyle pattern consisting of energy-dense diet, physical inactivity, smoking, and alcohol use. Such high risk profiles have been documented to be negatively associated with SES in middle- or high-income countries/regions [35-40], but positively associated with SES in low-income countries [41-44]. SES may affect health status through lifestyle choices [45], and healthy lifestyle was associated with lower risk of stroke [46,47]. SES also related to education and health literacy in populations, which in turn related to a lower risk of stroke [48,49]. Finally, SES is related to the accessibility and quality of health care services which are directly related to the prevention and treatment of stroke [24,49]. The association between stroke mortality and the HDI in the same time period was stronger than the association of stroke mortality with the HDI in an earlier time period for the same cohort. This may suggest that health care services play a more important role for the prognosis of stroke patients.

Our study examined the association between the risk of stroke and SES among countries/regions. In agreement with our results, some studies reported inverse associations between SES and stroke mortality in middle- or high-income countries/regions [14,15]. Studies from USA and northern European countries in the 1980s reported high stroke mortality in people with manual occupations and low mortality in the non-manual class [50]. An analysis from the 1990s assessed stroke mortality by educational level in ten European countries based on longitudinal data [51]. For all countries in all age groups, higher mortality rates were reported in groups with an education below upper secondary or equivalent. This was consistent for men (relative risk 1.27, 95% CI 1.24-1.30) and women (1.29, 1.27-1.32). In contrast, observations from low-income countries showed that populations with high socioeconomic status were at a higher risk of stroke compared with those with low socioeconomic status [16,17]. For instance, stroke mortality was higher in urban compared with rural Tanzania, there being a graded response depending on wealth. The yearly age-adjusted rates per 100,000 in the group aged 15–64 year for the three project areas (urban, fairly prosperous rural, and poor rural, respectively) were 65 (95% CI: 39–90), 44 (31–56), and 35 (22–48) for men, and 88 (48–128), 33 (22–43), and 27 (16–38) for women, respectively [17]. Our study indicated the high correlation between childhood and adulthood SES and therefore we could not determine if childhood/adulthood SES related with stroke risk independently of adulthood/childhood SES due to their colinearity. However, we found that stroke mortality in the countries/regions at the bottom tertile of HDI both in 1960 and 1999 was 2.52 and 2.61 times higher than those at the top tertile of HDI in both periods.

There are limitations in our study. Given the nature of the ecological study design, our results could be biased by the ecological fallacy. We could not completely rule out the possibility of residual confounding due to unmeasured or inadequately measured covariates. The results from the population level could not be directly applied to individual patients. HDI was a comprehensive country level index estimated with comparable information; therefore, the bias in SES measurement was limited. Data on stroke mortality is not available for very low-income countries/regions, so that the results only applied to low to middle or high income countries/regions. Stroke mortality at different time points could be affected by the changing of ICD codes system over time. In the present study, the data available comprise deaths for stroke registered in national vital registration systems, with underlying cause of death as coded by the relevant national authority. Moreover, our analyses are restricted to overall category of stroke which is essentially similar in the 8th and 9th, and 9th and 10th [4,52,53], and for which death certificate data are more accurate than for specific diseases. The accuracy and consistency over time and between regions in the diagnosis may affect the comparison of stroke mortality at different time periods among countries/regions. However, the concerns about diagnostic accuracy in these statistics are minimized by inclusion of all cerebrovascular disease for analysis, thus improving comparability across countries and time. We did not analyze subtypes of stroke mortality due to the unavailability of the data, and the study is not able to examine regional differences and time trends in mortality from different stroke subtypes. Different SES indicators can establish groups with differential exposures and identify specific as well as generic mechanisms relating SES to health [54]. There is no best single indicator. Heath is captured in HDI, so it could be a limitation to study HDI and health outcomes. However, HDI is a composite measure of the three factors key in allowing people to lead more fulfilling lives and strong association with stroke mortality. Therefore, it was used as the SES indicator in this study. It should be mentioned that there was no log-linear or quadratic linear association between HDI and mortality from other cardiovascular/vascular diseases were observed (data not shown here).

In conclusion, SES is an important population indicator of stroke mortality risk. From low to low-middle income countries/regions, stroke mortality increases with improvement of SES (measured by HDI). From middle to high income countries/regions, stroke mortality decreases with advancing SES. In low SES environment, advantaged populations are at high risk of stroke. In high SES environment, disadvantaged populations are at high risk of stroke. For the countries/regions experiencing transition, the high and low risk populations are under epidemiological transition. This information allows health policy makers to mobilize appropriate resources and identify target populations for more efficient health protection and better health care services.

Abbreviations

ARG: Argentina; AUS: Australia; AUT: Austria; BEL: Belgium; BGR: Bulgaria; BP: blood pressure; BRA: Brazil; CAN: Canada; CC: correlation coefficient; CHE: Switzerland; CHL: Chile; CHN: China; COL: Colombia; CRI: Costa rica; CZE: Czech republic; DEN: Denmark; DEU: Germany; ECU: Ecuador; ESP: Spain; FIN: Finland; FRA: France; FSE: Formerly socialist economies of Europe; GBR: United Kingdom; GDP: Gross domestic product; GRC: Greece; HDI: Human development index; HDR: Human development report; HKG: Hong kong; HPT: Prevalence of hypertension; HUN: Hungary; ICD: International classification of diseases; IFD: Infectious disease; IFD (‰): Permillage of infectious disease death/total deaths; IHD: Ischemic heart disease; IRL: Ireland; ISR: Israel; ITA: Italy; JPN: Japan; KOR: Korea republic of; LAC: Latin America and the caribbean; MEC: Middle eastern crescent; MEX: Mexico; M/F: Male/Female; MONICA: Multinational monitoring of determinants and trends in cardiovascular disease; MUS: Mauritius; NLD: Netherlands; NOR: Norway; NZL: New Zealand; OAI: Other Asia and islands; OB: Obese; PAN: Panama; POL: Poland; PRT: Portugal; PRY: Paraguay; RC: Regression coefficient; ROU: Romania; SBP: Systolic blood pressure; SD: Standard deviation; SES: Socioeconomic status; SF: Saturated fat; SGP: Singapore; SLV: El salvador; SMK: Smoking; SMRs: Standardized mortality ratios; SWE: Sweden; TC: Total cholesterol; TG: Triglycerides; UN: The United Nations; UNDP: The United Nations Development Program; URY: Uruguay; USA: United states of america; VEN: Venezuela; VS: Versus; WHO: The World Health Organization.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

XZ designed the study; SHW, XZ and JW conducted the research; SHW analyzed the data and drafted the paper; XZ had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The association of stroke mortality rate (1/100,000, log scale) in the latest available year with the Human Development Index (HDI) in 1980, 1985, 1990 and 1995 for the age group of 45-54y in men and women.

Contributor Information

Sheng Hui Wu, Email: shenghuiwu@hotmail.com.

Jean Woo, Email: jeanwoowong@cuhk.edu.hk.

Xin-Hua Zhang, Email: zhang_xh@hotmail.com.au.

References

- World Health Organization. World health report 2004-changing history. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Neglected global epidemics: three growing threats. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Global Health Statistics: A Compendium of Incidence, Prevalence, and Mortality Estimates for Over 200 Conditions. USA: The harvard school of public health on behalf of the world health organization and the world bank; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sarti C, Rastenyte D, Cepaitis Z. International trends in mortality from stroke, 1968 to 1994. Stroke. 2000;31(7):1588–1601. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.31.7.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global NCD infobase/online tool. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. http://www.who.int/ncd_surveillance/infobase/en. Accessed 10/10. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Statistical Information System (WHOSIS) Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. http://www3.who.int/whosis/. Accessed 12/20. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Database on Body Mass Index (BMI) : ; 2008. http://www.who.int/bmi. Accessed 11/10. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Ikeda K, Yamori Y. Changes in stroke mortality rates for 1950 to 1997: a great slowdown of decline trend in Japan. Stroke. 2001;32(8):1745–1749. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.32.8.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom TJ, Epstein FH. Heart disease, cancer, and stroke mortality trends and their interrelations. an international perspective. Circulation. 1994;90(1):574–582. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.90.1.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulpitt CJ. In: Handbook of Hypertension-Epiemiology of Hypertension. Bulpitt CJ, editor. : Elsevier Science B.V; 2000. Treatment of hypertension: the major trials; pp. 567–598. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RC, Schoeni RF. Early-life origins of adult disease: national longitudinal population-based study of the United States. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(12):2317–2324. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau AJ, Ling P, Palm F, Urbanek C. et al. Childhood and adult social conditions and risk of stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;33(4):385–391. doi: 10.1159/000336331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glymour MM, Avendaño M, Haas S. et al. Lifecourse social conditions and racial disparities in incidence of first stroke. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(12):904–912. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenland K, Hu S, Walker J. All-cause and cause-specific mortality by socioeconomic status among employed persons in 27 US states, 1984–1997. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(6):1037–1042. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.6.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Takano T. Cause-specific mortality differences across socioeconomic position of municipalities in Japan, 1973–1977 and 1993–1998: Increased importance of injury and suicide in inequality for ages under 75. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(1):100–109. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao SP, Mao JW, Hu JP. Mortality and the major causes of deaths in selected urban and rural populations in china. Chinese journal of health statistics. 1999;16(5):276–281. [Google Scholar]

- Walker RW, McLarty DG, Kitange HM. et al. Stroke mortality in urban and rural Tanzania. adult morbidity and mortality project. Lancet. 2000;355(9216):1684–1687. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Table 4: Estimated coverage of mortality data for latest year. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. http://www.who.int/whosis/database/mort/table4.cfm Accessed 12/20. [Google Scholar]

- Forsdahl A. Are poor living conditions in childhood and adolescence an important risk factor for arteriosclerotic heart disease? Br J Prev Soc Med. 1977;31(2):91–95. doi: 10.1136/jech.31.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattnayak SR, Shai D. Mortality rates as indicators of cross-cultural development: Regional variations in the third world. J Dev Soc. 1995;11(2):252–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom C, Lindstrom M. "Social capital," GNP per capita, relative income, and health: An ecological study of 23 countries. Int J Health Serv. 2006;36(4):679–696. doi: 10.2190/C2PP-WF4R-X081-W2QN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Program. Human Development Reports. : ; 2003. http://hdr.undp.org/reports/global/2003/faq.html#21. Accessed 01/06. [Google Scholar]

- Liberatos P, Link BG, Kelsey JL. The measurement of social class in epidemiology. Epidemiol Rev. 1988;10:87–121. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Health Atlas. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. http://www.who.int/globalatlas/dataQuery/default.asp. Accessed 12/11. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization. Geneva: Global Status Report on Alcohol; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics Annual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton J, Murphy ME, Khaw KT, Ebrahim SB, Davey SG. In: The Health of Adult Britain 1841–1994. Charlton JMM, editor. London: The Stationery Office; 1997. Cardiovascular diseases; pp. 60–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom JC, McQueen J, Connell JM, Whittle MJ. Fetal angiotensin II levels and vascular (type I) angiotensin receptors in pregnancies complicated by intrauterine growth retardation. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100(5):476–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb15276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn CN, Barker DJ, Osmond C. Mothers' pelvic size, fetal growth, and death from stroke and coronary heart disease in men in the UK. Lancet. 1996;348(9037):1264–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)04257-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Hales CN, Fall CH, Osmond C, Phipps K, Clark PM. Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia (syndrome X): relation to reduced fetal growth. Diabetologia. 1993;36(1):62–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00399095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DI, Hirst S, Clark PM, Hales CN, Osmond C. Fetal growth and insulin secretion in adult life. Diabetologia. 1994;37(6):592–596. doi: 10.1007/BF00403378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Martyn CN, Osmond C, Hales CN, Fall CH. Growth in utero and serum cholesterol concentrations in adult life. BMJ. 1993;307(6918):1524–1527. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6918.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Meade TW, Fall CH. et al. Relation of fetal and infant growth to plasma fibrinogen and factor VII concentrations in adult life. BMJ. 1992;304(6820):148–152. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6820.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn CN, Gale CR, Jespersen S, Sherriff SB. Impaired fetal growth and atherosclerosis of carotid and peripheral arteries. Lancet. 1998;352(9123):173–178. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez Roux AV, Chambless L, Merkin SS. et al. Socioeconomic disadvantage and change in blood pressure associated with aging. Circulation. 2002;106(6):703–710. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000025402.84600.CD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maty SC, Everson-Rose SA, Haan MN, Raghunathan TE, Kaplan GA. Education, income, occupation, and the 34-year incidence (1965–99) of type 2 diabetes in the alameda county study. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(6):1274–1281. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue RP, Orchard TJ, Kuller LH, Drash AL. Lipids and lipoproteins in a young adult population: the beaver county lipid study. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122(3):458–467. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Bowman BA, Marks JS, Koplan JP. The spread of the obesity epidemic in the United States, 1991–1998. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1519–1522. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood GA, Salsberry P, Ferketich AK, Wewers ME. Cigarette smoking, socioeconomic status, and psychosocial factors: examining a conceptual framework. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24(4):361–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis CB, Van Lenthe FJ, Giskes K, Huisman M, Brug J, Mackenbach JP. Socioeconomic status, environmental and individual factors, and sports participation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):71–81. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e318158e467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular Diseases Prevention Center of Ministry of Health of China. 2005 Report on Cardiovascular Diseases in China. 1. Beijing: Encyclopedia of China Publishing House; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Jaramillo P, Casas JP, Bautista L, Serrano NC, Morillo CA. An integrated proposal to explain the epidemic of cardiovascular disease in a developing country. from socioeconomic factors to free radicals. Cardiology. 2001;96(1):1–6. doi: 10.1159/000047379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Man QQ, Wang CR. et al. The plasma lipids level in adults among different areas in China. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2005;39(5):302–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Stamler J, Xiao Z, Folsom A, Tao S, Zhang H. Serum uric acid and its correlates in Chinese adult populations, urban and rural, of Beijing: the PRC-USA collaborative study in cardiovascular and cardiopulmonary epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(2):288–296. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Symons M, Popkin B. Contrasting socioeconomic profiles related to healthier lifestyles in china and the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(2):184–191. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenstrom E, Boysen G, Nyboe J. Lifestyle factors and risk of cerebrovascular disease in women: the Copenhagen city heart study. Stroke. 1993;24(10):1468–1472. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.24.10.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden-Albala B, Sacco RL. Lifestyle factors and stroke risk: Exercise, alcohol, diet, obesity, smoking, drug use, and stress. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2000;2(2):160–166. doi: 10.1007/s11883-000-0111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Steptoe A. Socioeconomic differences in attitudes and beliefs about healthy lifestyles. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(6):440–443. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.6.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Nordhorn J, Nolte CH, Rossnagel K. et al. Knowledge about risk factors for stroke: a population-based survey with 28,090 participants. Stroke. 2006;37(4):946–950. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000209332.96513.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst AE, del Rios M, Groenhof F, Mackenbach JP. Socioeconomic inequalities in stroke mortality among middle-aged men: an international overview. European Union working group on socioeconomic inequalities in health. Stroke. 1998;29(11):2285–2291. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.29.11.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avendano M, Kunst AE, Huisman M. et al. Educational level and stroke mortality: a comparison of 10 European populations during the 1990s. Stroke. 2004;35(2):432–437. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000109225.11509.EE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokotailo RA, Hill MD. Coding of stroke and stroke risk factors using international classification of diseases, revisions 9 and 10. Stroke. 2005;36(8):1776–1781. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000174293.17959.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparability across revisions for selected causes. : ; 2008. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/comp2.pdf. Accessed 01/25. [Google Scholar]

- Naess O, Claussen B, Thelle DS, Smith GD. Four indicators of socioeconomic position: relative ranking across causes of death. Scand J Public Health. 2005;33:215–221. doi: 10.1080/14034940410019190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The association of stroke mortality rate (1/100,000, log scale) in the latest available year with the Human Development Index (HDI) in 1980, 1985, 1990 and 1995 for the age group of 45-54y in men and women.