Abstract

Background

Moraxella catarrhalis is a human-specific gram-negative bacterium readily isolated from the respiratory tract of healthy individuals. The organism also causes significant health problems, including 15-20% of otitis media cases in children and ~10% of respiratory infections in adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The lack of an efficacious vaccine, the rapid emergence of antibiotic resistance in clinical isolates, and high carriage rates reported in children are cause for concern. Virtually all Moraxella catarrhalis isolates are resistant to β-lactam antibiotics, which are generally the first antibiotics prescribed to treat otitis media in children. The enzymes responsible for this resistance, BRO-1 and BRO-2, are lipoproteins and the mechanism by which they are secreted to the periplasm of M. catarrhalis cells has not been described.

Results

Comparative genomic analyses identified M. catarrhalis gene products resembling the TatA, TatB, and TatC proteins of the well-characterized Twin Arginine Translocation (TAT) secretory apparatus. Mutations in the M. catarrhalis tatA, tatB and tatC genes revealed that the proteins are necessary for optimal growth and resistance to β-lactams. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to replace highly-conserved twin arginine residues in the predicted signal sequence of M. catarrhalis strain O35E BRO-2, which abolished resistance to the β-lactam antibiotic carbanecillin.

Conclusions

Moraxella catarrhalis possesses a TAT secretory apparatus, which plays a key role in growth of the organism and is necessary for secretion of BRO-2 into the periplasm where the enzyme can protect the peptidoglycan cell wall from the antimicrobial activity of β-lactam antibiotics.

Background

Moraxella catarrhalis is a Gram-negative bacterium primarily associated with otitis media in children and respiratory infections in adults with compromised lung function, particularly patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). The organism is also readily isolated from the upper respiratory tract of healthy individuals and thus was considered a commensal bacterium until relatively recently. The rate of colonization by M. catarrhalis varies depending on many factors such as age, socioeconomic status, geography, and overall health condition. It has been reported that ~2/3 of children are colonized in their first year of life and 3-5% of adults carry the organism asymptomatically. Following initial colonization, there is a high rate of turnover, indicating continual clearance and re-colonization by new strains [1-27].

Moraxella catarrhalis possesses several virulence determinants that enable it to persist in the human respiratory tract. A number of molecules in the outer membrane have been shown to contribute to adherence, allowing M. catarrhalis to bind and colonize the host mucosa. These include LOS, UspA1, UspA2H, McaP, OMPCD, Hag/MID, MhaB1, MhaB2, MchA1, MchA2, and the type IV pilus [28-37]. In order to persist following colonization, M. catarrhalis possesses several mechanisms to evade the host immune system including resistance to complement. The best studied of these being UspA2 and UspA2H, which bind the C4-binding protein, C3 and vitronectin [38-41], as well as CopB, OMPCD, OmpE, and LOS [31,37,42,43].

Moraxella catarrhalis is often refractory to antibiotic treatment. Over 90% of isolates have been shown to possess a beta-lactamase, making them resistant to penicillin-based antibiotics [44-51], which are typically prescribed first to treat otitis media. The genes specifying this resistance appear to be of Gram-positive origin [52,53], suggesting that M. catarrhalis can readily acquire genes conferring resistance to additional antibiotics via horizontal transfer. Additionally, recent evidence has shown that M. catarrhalis persists as a biofilm in vivo, giving it further protection from antibiotic treatment and the host immune response [54-58].

The bacterial twin-arginine translocation (TAT) system mediates secretion of folded proteins across the cytoplasmic membrane. The TAT apparatus typically consists of three integral membrane proteins, namely TatA, TatB, and TatC. TatA forms the pore through which TAT substrates are secreted whereas TatB and TatC are important for binding and directing the substrates to the TatA pore. TatC acts as the gatekeeper for the secretion apparatus and specifically recognizes TAT substrates via a well-conserved signal sequence [59-62]. This signal sequence is similar to that of the general secretory system in that it possesses N- (neutral), H- (hydrophobic), and C- (charged) regions, but also contains a TAT-recognition motif (S/T-R-R-x-F-L-K) exhibiting nearly invariable twin arginines (RR) followed by two uncharged residues [59-62]. Proteins secreted via the TAT system are often, but not limited to, proteins that bind cofactors in the cytoplasm prior to transport, such as those involved in respiration and electron transport, and proteins that bind catalytic metal ions [59-62]. The TAT system has also been shown to secrete several factors important for bacterial pathogenesis including iron acquisition, flagella synthesis, toxins, phospholipases, and beta-lactamases [59,62-74]. In this study, we identified genes encoding a TAT system in M. catarrhalis and mutated these genes in order to elucidate the role of this translocase in the secretion of proteins that may be important for pathogenesis.

Results and discussion

Identification of tatA, tatB and tatC genes in M. catarrhalis

Analysis of the patented genomic sequence of M. catarrhalis strain ATCC43617 using NCBI’s tblastn service (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) identified an ORF (nucleotides 267,266 to 266,526 of GenBank accession number AX06766.1) that encodes a protein similar to the tatC gene product of Pseudomonas stutzeri[75] (expect value of 7e-56). TatC is the most highly-conserved component of the TAT system among organisms known (or predicted) to utilize this particular secretion apparatus [59-62]. TatC is located in the cytoplasmic membrane, typically contains 6 membrane-spanning regions, and plays a key role in recognizing the twin-arginine motif in the signal sequence of molecules secreted by the TAT system. The M. catarrhalis ATCC43617 tatC-like ORF specifies a 27-kDa protein of 247 amino acids, and analysis using the TMPred server (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html) revealed that it contains 6 potential membrane-spanning domains (data not shown).

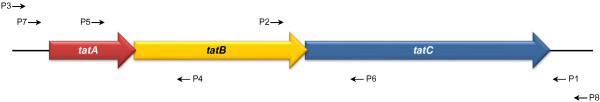

Sequence analysis upstream of the M. catarrhalis tatC ortholog identified gene products similar to other conserved components of the TAT system, TatA and TatB (Figure 1). The ORF immediately upstream encodes a 178-residue protein with a molecular weight of 20-kDa that resembles TatB of Providencia stuartii [76] (expect value of 3e-8). Upstream of the M. catarrhalis tatB-like gene, we identified an ORF specifying a 9-kDa protein of 77 aa that is most similar to TatA of Xanthomonas oryzae [77] (expect value of 2e-5). TatA and TatB are cytoplasmic proteins anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane via hydrophobic N-termini. TatB forms a complex with TatC often referred to as the twin-arginine motif recognition module, while TatA oligomerizes and forms a channel that is used to secrete TAT substrates [59-62]. Both M. catarrhalis ATCC43617 TatA (aa 4–21) and TatB (aa 5–21) orthologs are predicted to contain hydrophobic membrane-spanning domains in their N-termini using TMPred (data not shown). Together, these observations suggest that M. catarrhalis possesses a functional TAT system.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the M. catarrhalis tatABC locus. The relative position of tat-specific oligonucleotide primers (P1-P8) used throughout the study is shown (see Methods section for details).

To assess the presence and conservation of the tat genes in other M. catarrhalis isolates, we amplified and sequenced these genes from strains O35E, O12E, McGHS1, V1171, and TTA37. The encoded gene products were then compared using ClustalW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/). Of note, the annotated genomic sequence of the M. catarrhalis isolate BBH18 has been published [78] and the predicted aa sequence of the TatA (MCR_0127, GenBank accession number ADG60399.1), TatB (MCR_0126, GenBank accession number ADG60398.1) and TatC (MCR_0125, GenBank accession number ADG60397.1) proteins were included in our comparative analyses. Overall, the TatA and TatC proteins are perfectly conserved. The TatB proteins divide the strains into two groups where O35E, McGHS1, TTA37, ATCC43617, and BBH18 are 100% identical to each other, while O12E and V1171 both contain the same aa substitution at residue 38 (S in lieu of G). We also noted that in all isolates examined, the tatA and tatB ORFs overlap by one nucleotide. A similar one-nucleotide overlap is also observed for the tatB and tatC coding regions. This observation suggests that the M. catarrhalis tatA, tatB, and tatC genes are transcriptionally and translationally linked.

The M. catarrhalis tatA, tatB and tatC genes are necessary for optimal growth

To study the functional properties of the Tat proteins in M. catarrhalis, we constructed a panel of isogenic mutant strains of isolate O35E in which the tatA, tatB and tatC genes were disrupted with a kanamycin resistance (kanR) marker. Each mutant was also complemented with a plasmid encoding a wild-type (WT) copy of the mutated tat gene and/or with a plasmid specifying the entire tatABC locus. A growth defect was immediately noted in the tat mutants as ~40-hr of growth at 37°C was necessary for isolated colonies of appreciable size to develop on agar plates, compared to ~20-hr for the parent strain O35E. Hence, we compared the growth of the tat mutants to that of the WT isolate O35E in liquid medium under aerobic conditions. This was accomplished by measuring the optical density (OD) of cultures over a 7-hr period. In some of these experiments, we also plated aliquots of the cultures to enumerate colony forming units (CFU) as a measure of bacterial viability.

As shown in Figure 2A, the tatA, tatB and tatC mutants carrying the control plasmid pWW115 had lower OD readings than their progenitor strain O35E throughout the entire course of the experiments. Significant differences in the number of CFU were also observed between mutants and WT strains (Figure 2B). Together, these results demonstrate that mutations in the tatA, tatB and tatC genes substantially reduce the growth rate of M. catarrhalis cells. Complementation of the tatA (Figure 3A) and tatB (Figure 3B) mutants with plasmids encoding WT tatA (i.e. pRB.TatA) or tatB (i.e. pRB.TatB) did not rescue the growth phenotype of these strains. However, the construct pRB.TAT, which specifies the entire tatABC locus, restored growth of the tatA and tatB mutants to WT levels (Figure 3A and B). These results support the hypothesis that the tatA, tatB and tatC genes are transcriptionally and translationally linked due to the one nucleotide overlaps between the tatA and tatB, as well as the tatB and tatC ORFs. For the tatC mutant, O35E.TC, introduction of the plasmid pRB.TatC, which encodes only the tatC gene, is sufficient to restore growth to WT levels (Figure 3C). This finding is consistent with the above observations since tatC is located downstream of tatA and tatB (Figure 1), thus it is unlikely that a mutation in tatC would affect the expression of either the tatA or tatB gene product. A tatC mutation was also engineered in the M. catarrhalis isolate O12E. The resulting strain, O12E.TC, exhibited a growth defect comparable to that of the tatC mutant of strain O35E, and this growth defect was rescued by the plasmid pRB.TatC (data not shown). These results demonstrate that the importance of the TAT system to M. catarrhalis growth is not a strain-specific occurrence. Of note, all tat mutants carrying the control plasmid pWW115 grew at rates comparable to the mutants containing no plasmid (data not shown).

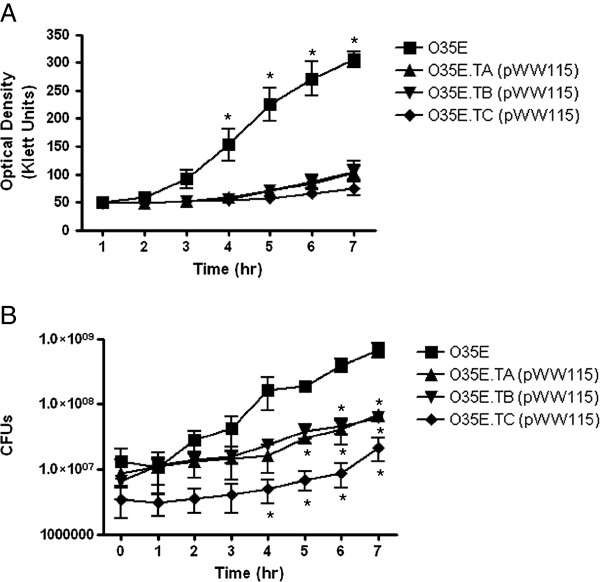

Figure 2.

Growth of the M. catarrhalis WT isolate O35E and tat mutant strains in liquid medium. Plate-grown bacteria were used to inoculate sidearm flasks containing 20-mL of broth to an optical density (OD) of ~50 Klett units. The cultures were then incubated with shaking at a temperature of 37°C for seven hours. The OD of each culture was determined every 60-min using a Klett Colorimeter. Results are expressed as the mean OD ± standard error (Panel A). Aliquots (1-mL) were taken out of each culture after recording the OD, diluted, and spread onto agar plates to determine the number of viable colony forming units (CFU). Results are expressed as the mean CFU ± standard error (Panel B). Growth of the wild-type (WT) isolate O35E is compared to that of its tatA (O35E.TA), tatB (O35E.TB), and tatC (O35E.TC) isogenic mutant strains carrying the control plasmid pWW115. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference in the growth rates of mutant strains compared to that of the WT isolate O35E.

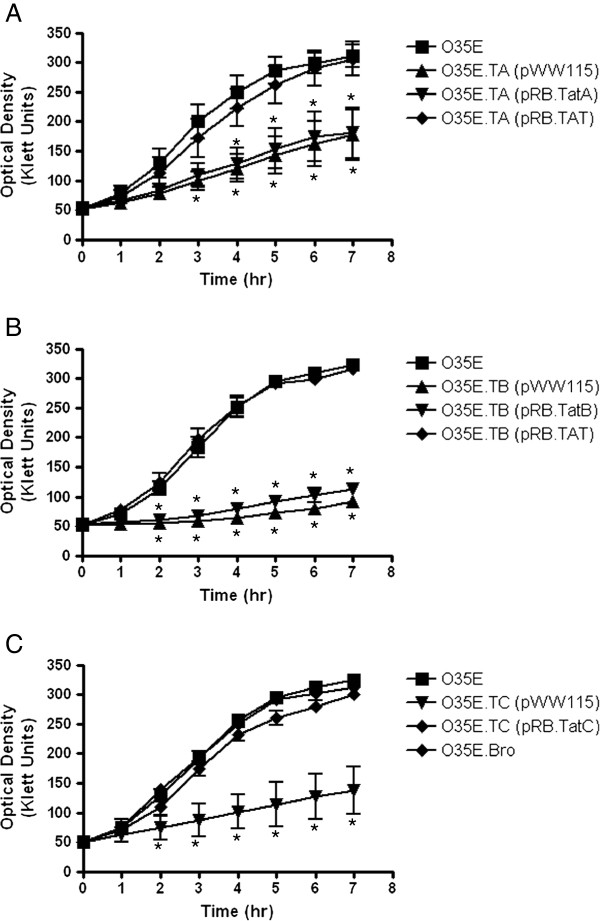

Figure 3.

Growth of the M. catarrhalis WT isolate O35E and tat mutant strains in liquid medium. Plate-grown bacteria were used to inoculate sidearm flasks containing 20-mL of broth to an OD of 50 Klett units. The cultures were then incubated with shaking at a temperature of 37°C for seven hours. The OD of each culture was determined every 60-min using a Klett Colorimeter. Panel A: Growth of O35E is compared to that of its tatA isogenic mutant strain, O35E.TA, carrying the plasmid pWW115 (control), pRB.TatA (specifies a WT copy of tatA), and pRB.TAT (harbors the entire tatABC locus). Panel B: Growth of O35E is compared to that of its tatB isogenic mutant strain, O35E.TB, carrying the plasmid pWW115, pRB.TatB (specifies a WT copy of tatB), and pRB.TAT. Panel C: Growth of O35E is compared to that of its tatC isogenic mutant strain, O35E.TC, carrying the plasmid pWW115 and pRB.TatC (contains a WT copy of tatC). Growth of the bro-2 isogenic mutant strain O35E.Bro is also shown. Results are expressed as the mean OD ± standard error. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference in the growth rates of mutant strains compared to that of the WT isolate O35E.

The tatA, tatB and tatC genes are necessary for the secretion of β-lactamase by M. catarrhalis

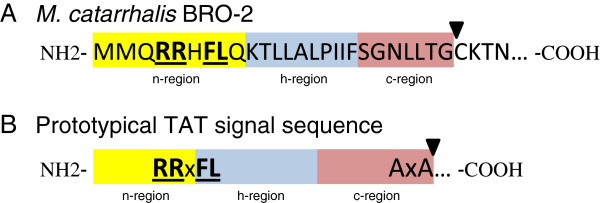

TAT-deficient mutants of E. coli [79] and mycobacteria [72-74,80] have been previously shown to be hypersensitive to antibiotics, including β-lactams. Moreover, the β-lactamases of M. smegmatis (BlaS) and M. tuberculosis (BlaC) have been shown to possess a twin-arginine motif in their signal sequences and to be secreted by a TAT system [74]. More than 90% of M. catarrhalis isolates are resistant to β-lactam antibiotics [44-51]. The genes responsible for this resistance, bro-1 and bro-2, specify lipoproteins of 33-kDa that are secreted into the periplasm of M. catarrhalis where they associate with the inner leaflet of the outer membrane [52,53]. Analysis of the patented genomic sequence of M. catarrhalis strain ATCC43617 with NCBI’s tblastn identified the bro-2 gene product (nucleotides 8,754 to 7,813 of GenBank accession number AX067438.1), which is predicted to encode a protein of 314 residues with a predicted MW of 35-kDa. The first 26 residues of the predicted protein were found to specify characteristics of a signal sequence (i.e. n-, h-, and c-region; see Figure 4A). Analysis with the LipoP server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/LipoP/) indicated a signal sequence cleavage site between residues 26 and 26 (i.e. TG26▼C27K) of BRO-2 (arrowhead in Figure 4A), which would provide a free cysteine residue for lipid modification of this lipidated β-lactamase [52]. Of significance, the putative signal sequence of BRO-2 contains the highly-conserved twin-arginine recognition motif RRxFL (Figure 4), thus suggesting that the gene product is secreted via a TAT system. Of note, analysis of M. catarrhalis BRO-1 sequences available through the NCBI database indicates that the molecules also contain the twin-arginine recognition motif (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Features of the M. catarrhalis BRO-2 signal sequence. The M. catarrhalis ATCC43617 bro-2 gene product was analyzed using the SignalP 4.0 server. Panel A: The first 30 amino acid of BRO-2 are shown. Residues 1–26 specify characteristics of a prokaryotic signal sequence, specifically neutral (n, highlighted in yellow), hydrophobic (h, highlighted in blue) and charged (c, highlighted in red) regions. The highly-conserved twin-arginine recognition motif is bolded and underlined. Panel B: Features of a typical TAT signal sequence where x represents any amino acid (adapted from [59]). The arrowheads indicate signal peptidase cleavage sites.

Based on these findings, we compared the ability of our panel of WT and tat mutant strains to grow in the presence of the β-lactam antibiotic carbenicillin. This was accomplished by spotting equivalent numbers of bacteria onto agar plates supplemented with the antibiotic. For comparison, bacteria were also spotted onto agar plates without carbenicillin. These plates were incubated for 48-hr at 37°C to accommodate the slower growth rate of tat mutants. In contrast to WT M. catarrhalis O35E, which is resistant to carbenicillin, the tatA (Figure 5A), tatB (Figure 5B), and tatC (Figure 5C) mutants were sensitive to the antibiotic. The introduction of plasmids containing a WT copy of tatA (i.e. pRB.TatA, Figure 5A) and tatB (i.e. pRB.TatB, Figure 5B) did not restore the ability of the tatA and tatB mutants to grow in the presence of carbenicillin, respectively. Resistance to the β-lactam was observed only when the tatA and tatB mutants were complemented with the plasmid specifying the entire tatABC locus (see pRB.TAT in Figure 5A and B), which is consistent with the results of the growth experiments presented in Figure 3. Introduction of the plasmid encoding only the WT copy of tatC (i.e. pRB.TatC) in the strain O35E.TC was sufficient to restore the growth of this tatC mutant on medium supplemented with carbenicillin (Figure 5C). Of note, the tatC mutant of strain O12E was tested in this manner and the results were consistent with those obtained with O35E.TC (data not shown). In order to provide an appropriate control for these experiments, an isogenic mutant strain of M. catarrhalis O35E was constructed in which the bro-2 gene was disrupted with a kanR marker. The mutant, which was designated O35E.Bro, grew at the same rate as the parent strain O35E in liquid medium (Figure 3C). As expected, the bro-2 mutant did not grow on agar plates containing carbenicillin (Figure 5C).

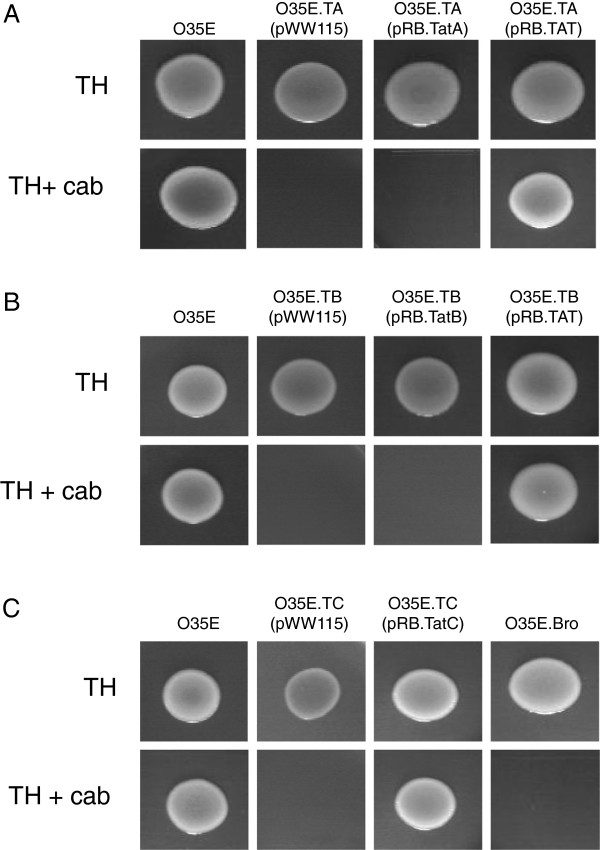

Figure 5.

Growth of the M. catarrhalis WT isolate O35E and tat mutant strains in the presence of the β-lactam antibiotic carbenicillin. The ability of tat mutants to grow in the presence of carbenicillin (cab) was tested by spotting equivalent numbers of bacteria onto Todd-Hewitt agar plates supplemented with the antibiotic (TH + cab). As control, bacteria were also spotted onto agar plates without carbenicillin (TH). These plates were incubated for 48 hrs at 37°C to accommodate the slower growth rate of the tat mutants. Panel A: Growth of O35E is compared to that of its tatA isogenic mutant strain, O35E.TA, carrying the plasmid pWW115 (control), pRB.TatA (specifies a WT copy of tatA), and pRB.TAT (harbors the entire tatABC locus). Panel B: Growth of O35E is compared to that of its tatB isogenic mutant strain, O35E.TB, carrying the plasmid pWW115, pRB.TatB (specifies a WT copy of tatB), and pRB.TAT. Panel C: Growth of O35E is compared to that of its tatC isogenic mutant strain, O35E.TC, carrying the plasmid pWW115 and pRB.TatC (contains a WT copy of tatC). Growth of the bro-2 isogenic mutant strain O35E.Bro is also shown. The results are shown as a composite image representative of individual experiments that were performed in duplicate on at least 3 separate occasions.

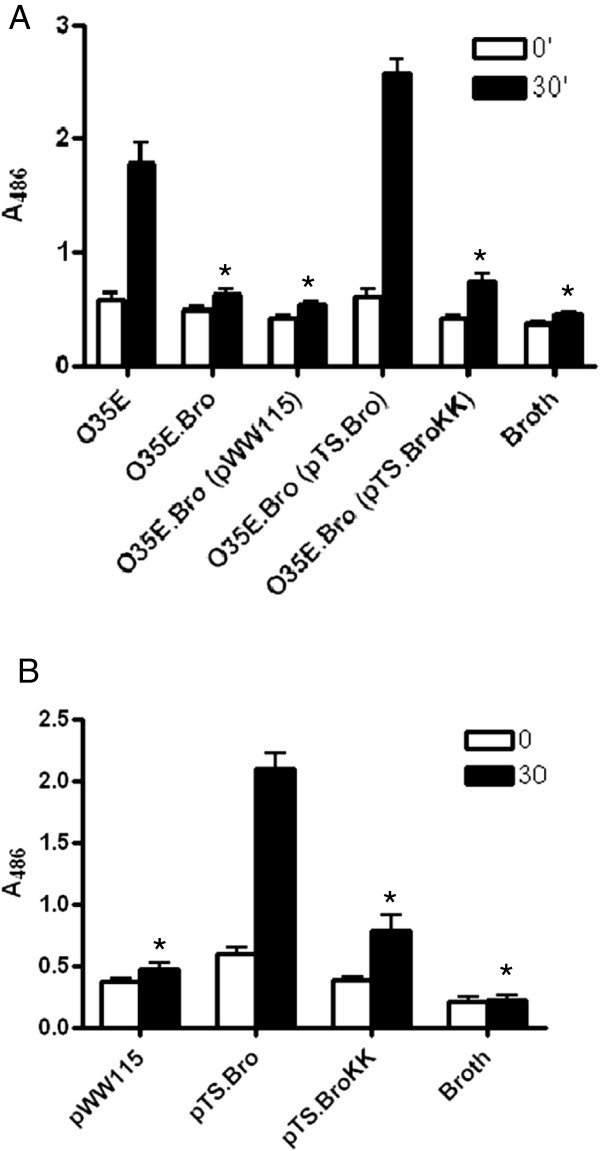

The effect of tat mutations on the β-lactamase activity of M. catarrhalis was quantitatively measured using the chromogenic β-lactamase substrate nitrocefin. These assays were performed using suspensions of freshly plate-grown bacteria placed into the wells of a 48-well tissue culture plate. A solution containing nitrocefin was added to these suspensions and the change of color from yellow to red (indicative of cleavage of the β-lactam ring) was monitored by measuring the absorbance of well contents at a wavelength of 486 nm. Substantially less β-lactamase activity was observed for the tatA, tatB and tatC mutants compared to the WT strain O35E (Figure 6). Complementation of the tatA and tatB mutants with plasmids containing only the WT copies of the inactivated genes did not restore β-lactamase activity, as expected based on the results of the experiments depicted in Figures 3 and 5. The plasmid pRB.TAT, which specifies the entire tatABC locus, restored the ability of the mutants O35E.TA (Figure 6A) and O35E.TB (Figure 6B) to hydrolyze nitrocefin. The plasmid pRB.TatC was sufficient to rescue β-lactamase activity in the tatC mutant strain O35E.TC to near WT levels (Figure 6C). The tatC mutant of strain O12E was tested in this manner and the results were consistent with those obtained with O35E.TC (data not shown). The control strain, O35E.Bro, was impaired in its ability to hydrolyze nitrocefin at levels comparable to those of the tatA, tatB and tatC mutants (Figure 6A, B and C). Taken together, these results suggest that the M. catarrhalis tatABC locus is necessary for secretion of the β-lactamase BRO-2 into the periplasm where the enzyme can protect the peptidoglycan cell wall from the antimicrobial activity of β-lactam antibiotics.

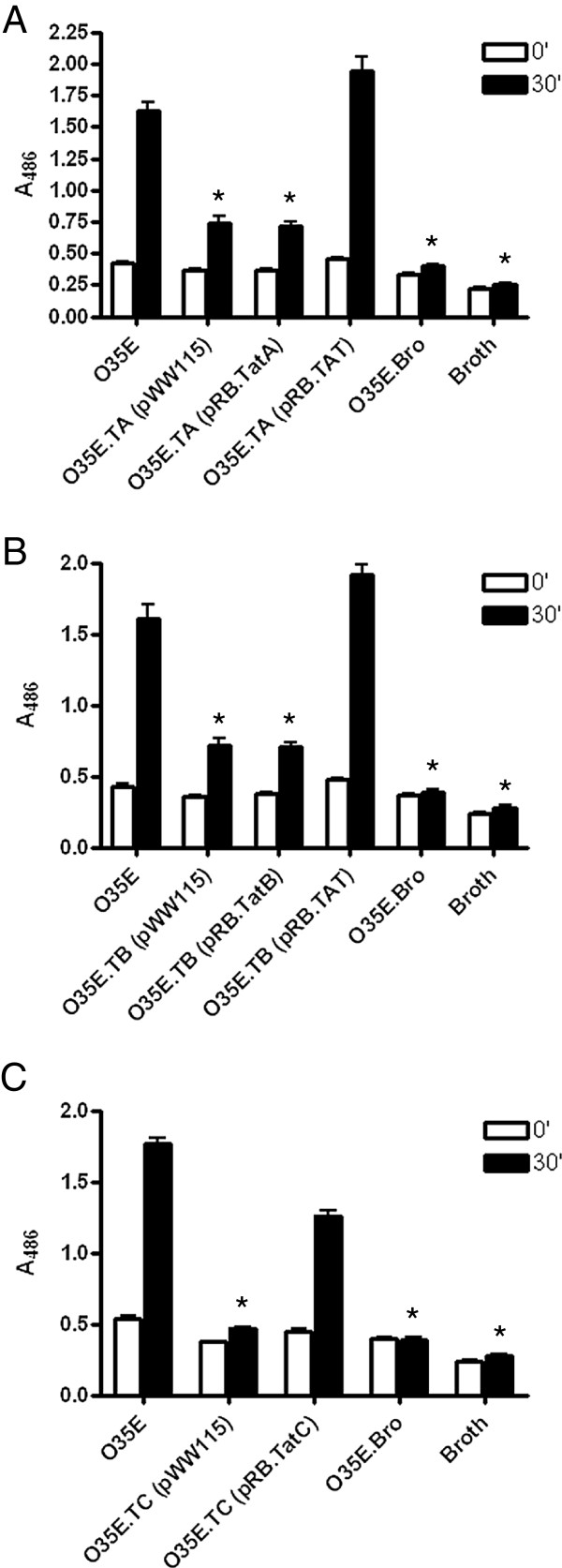

Figure 6.

Quantitative measurement of the β-lactamase activity produced by the M. catarrhalis WT isolate O35E and tat mutant strains. The β-lactamase activity of strains was measured using the chromogenic compound nitrocefin. Bacterial suspensions were mixed with a 250 μg/mL nitrocefin solution and the absorbance at 486 nm (A486) was immediately measured and recorded as time “0” (open bars). The A486 of the samples was measured again after a 30-min incubation at room temperature (black bars). Panel A: The β-lactamase activity of O35E is compared to that of the tatA mutant strain, O35E.TA, carrying the plasmid pWW115 (control), pRB.TatA (specifies a WT copy of tatA), and pRB.TAT (harbors the entire tatABC locus). Panel B: The β-lactamase activity of O35E is compared to that of the tatB mutant, O35E.TB, carrying the plasmid pWW115, pRB.TatB (specifies a WT copy of tatB), and pRB.TAT. Panel C: The β-lactamase activity of O35E is compared to that of the tatC mutant, O35E.TC, carrying the plasmid pWW115 and pRB.TatC (contains a WT copy of tatC). The strain O35E.Bro, which lacks expression of the β-lactamase BRO-2, was used as a negative control in all experiments in addition to the broth-only control. The results are expressed as the mean A486 ± standard error. Asterisks indicate that the reduction in the β-lactamase activity of mutants is statistically significant (P < 0.05) when compared to the WT strain O35E.

To conclusively demonstrate that M. catarrhalis BRO-2 is secreted by the TAT system, we cloned the bro-2 gene of strain O35E in the plasmid pWW115 (pTS.Bro) and used site-directed mutagenesis to replace the twin-arginine (RR) residues in BRO-2’s predicted signal sequence (Figure 4A) with twin lysine (KK) residues (pTS.BroKK). Similar conservative substitutions have been engineered in TAT substrates of other bacteria to demonstrate the importance of the RR motif in TAT-dependent secretion [74]. These plasmids were introduced in the mutant O35E.Bro and the recombinant strains were tested for their ability to hydrolyze nitrocefin. As shown in Figure 7A, expression of the mutated BRO-2 from plasmid pTS.BroKK did not restore the ability to hydrolyze nitrocefin. These results establish that the M. catarrhalis β-lactamase BRO-2 is secreted into the periplasm by the TAT system. Interestingly, the mutation in the RR motif of BRO-2 also interfered with secretion of the β-lactamase by recombinant Haemophilus influenzae DB117 bacteria (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Quantitative measurement of the β-lactamase activity of M. catarrhalis and recombinant H. influenzae strains. β-lactamase activity was measured using the chromogenic compound nitrocefin. Bacterial suspensions were mixed with a 250 μg/mL nitrocefin solution and the A486 was immediately measured and recorded as time “0” (open bars). The A486 of the samples was measured again after a 30-min incubation at room temperature (black bars). Panel A: The β-lactamase activity of M. catarrhalis O35E is compared to that of the bro-2 mutant, O35E.Bro, carrying plasmids pWW115, pTS.Bro, and pTS.BroKK. Panel B: The β-lactamase activity of H. influenzae DB117 carrying plasmids pWW115, pTS.Bro, and pTS.BroKK is compared. Sterile broth was used as a negative control in these experiments. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard error A486. Asterisks indicate that the reduction in the β-lactamase activity of strains lacking expression of BRO-2, or expressing a mutated BRO-2 that contains two lysine residues in its signal sequence instead of 2 arginines, is statistically significant (P < 0.05) when compared to bacteria expressing a WT copy of the bro-2 gene.

Identification of other M. catarrhalis gene products potentially secreted by the TAT system

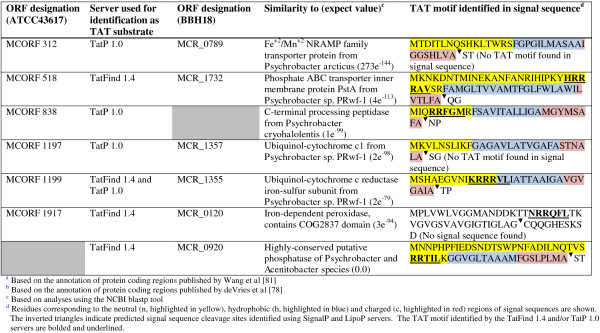

To identify other M. catarrhalis molecules that may be secreted via the TAT apparatus, the annotated genomic sequences of strains ATCC43617 [81] and BBH18 [78] were analyzed with prediction algorithms available through the TatFind 1.4 [82] and TatP 1.0 [83] servers. Although these servers are designed for the same purpose (i.e. identify proteins secreted by the TAT system), the algorithms used for each differ and as such proteins identified as TAT substrates do not overlap 100% between the two prediction algorithms.

Six ORFs were predicted to be TAT substrates in strain ATCC43617, only one of which was identified by both algorithms (Figure 8). The TatP 1.0 server identified MCORF 312 and MCORF 1197 as proteins potentially secreted by the TAT system, but no twin-arginine motif was found within the signal sequences of these gene products. Conversely, the TatFind 1.4 server identified MCORF 1917 as a TAT substrate and a twin-arginine motif was observed between residues 18 and 23. Although the encoded protein does not specify characteristics of a prokaryotic signal sequence (i.e. n-, h-, c-region), a potential lipoprotein signal sequence cleavage site was identified using the LipoP server. Interestingly, the MCORF 1197 and MCORF 1199 gene products resemble cytochrome c molecules involved in the electron transport chain. Cytochromes have been predicted, as well as demonstrated, to be TAT substrates in several bacterial species [84-87]. MCORF 1917 exhibits similarities to iron-dependent peroxidases, which is consistent with the previously reported role of the TAT system in the secretion of enzymes that bind metal ions, while MCORF 518 resembles the phosphate ABC transporter inner membrane protein PstA [88]. MCORF 838 shows similarities to a family of C-terminal processing peptidases and contains important functional domains including a post-translational processing, maturation and degradation region (PDZ-CTP), and a periplasmic protease Prc domain described as important for cell envelope biogenesis.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the putative TAT substrates identified in the genomes of M. catarrhalis strains ATCC43617a and BBH18b.

Six putative TAT substrates were identified in the genome of M. catarrhalis strain BBH18, five of which overlapping those predicted in ATCC43617 (Figure 8). Strain BBH18 specifies the unique TAT substrate MCR_920, which is predicted to be a highly-conserved phosphatase (Figure 8). The MCORF 1659 of strain ATCC43617 encodes a gene product that is 96.8% identical to this putative phosphatase, but neither of the TatFind 1.4 and TatP 1.0 servers identified the ORF as a TAT substrate, likely due to significant amino acid divergence in the signal sequence (data not shown). Strain BBH18 specifies a putative C-terminal processing peptidase (MCR_1063) that is 98.1% identical to the putative TAT substrate MCORF 838 of ATCC43617. Like the MCORF 838 of ATCC43617, the BBH18 gene product lacked a TAT motif in its signal sequence (data not shown). Despite these similarities, the BBH18 MCR_1063 C-terminal processing peptidase was not identified as a being potential TAT substrate by the TatFind 1.4 or TatP 1.0 algorithms.

Conclusions

This report is the first characterization of a secretory apparatus for M. catarrhalis. Our data demonstrate that the TAT system mediates secretion of β-lactamase and is necessary for optimal growth of the bacterium. Moraxella catarrhalis is a leading cause of otitis media worldwide along with Streptococcus pneumoniae and non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi), and is often found in mixed infections with these organisms [1-8,89]. In contrast to M. catarrhalis, most S. pneumoniae and NTHi isolates are susceptible to β-lactam antibiotics [90]. In a set of elegant studies, Schaar et al. demonstrated that outer membrane vesicles produced by M. catarrhalis contain β-lactamase and function as a long-distance delivery system to confer antimicrobial resistance for β-lactamase negative isolates of S. pneumoniae and NTHi [91]. This constitutes a novel mechanism by which M. catarrhalis promotes survival and infection by other pathogens in the context of polymicrobial disease. Hence, a greater understanding of the TAT secretion system of M. catarrhalis is a key area of future study as it may lead to the development of innovative strategies to improve the efficacy of existing antimicrobials used to treat bacterial infections by common childhood pathogens. Small molecular weight compounds that selectively inhibit TAT secretion in M. catarrhalis could be used in concert with β-lactam antibiotics as β-lactamase inhibitors. This hypothesis is supported by the recent discovery that the compounds N-phenyl maleimide and Bay 11–7782 specifically interfere with TAT-dependent secretion of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa phospholipase C PlcH [92].

Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

Strains and plasmids are described in Table 1. M. catarrhalis was cultured using Todd-Hewitt (TH) medium (BD Diagnostic Systems) supplemented with 20 μg/mL kanamycin, 15 μg/mL spectinomycin, and/or 5 μg/mL carbenicillin, where appropriate. Escherichia coli was grown using Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (Fisher BioReagents) supplemented with 15 μg/mL chloramphenicol and/or 50 μg/mL kanamycin, where indicated. Haemophilus influenzae was cultured using Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) medium (BD Diagnostic Systems) supplemented with 50 mg/L hemin chloride (Sigma-Aldrich®) and 10 mg/L NAD (Sigma-Aldrich®) (BHI + Heme + NAD). This medium was further supplemented with 50 μg/mL spectinomycin where appropriate. Electrocompetent M. catarrhalis and H. influenzae cells were prepared as previously described [93]. All strains were cultured at 37°C in the presence of 7.5% CO2.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

|

M. catarrhalis |

|

|

| O35E |

WT isolate from middle ear effusion (Dallas, TX) |

[94] |

| O35E.TA |

tatA isogenic mutant of strain O35E, kanR |

This study |

| O35E.TB |

tatB isogenic mutant of strain O35E, kanR |

This study |

| O35E.TC |

tatC isogenic mutant of strain O35E, kanR |

This study |

| O35E.Bro |

bro-2 isogenic mutant of strain O35E, kanR |

This study |

| O12E |

WT isolate from middle ear effusion (Dallas, TX) |

[28] |

| O12E.TC |

tatC isogenic mutant of strain O12E, kanR |

This study |

| McGHS1 |

WT isolate from patient with respiratory infection (Toledo, OH) |

[33] |

| TTA37 |

WT isolate from transtracheal aspirate (Johnson City, TN) |

[28] |

| V1171 |

WT isolate from nasopharynx of a healthy child (Chapel Hill, NC) |

[28] |

|

H. influenzae |

|

|

| DB117 |

Host strain for cloning experiments with pWW115 |

[95,96] |

|

E. coli |

|

|

| EPI300 |

Cloning strain |

Epicentre® |

| Illumina® | ||

| Plasmids |

|

|

| pCC1 |

Cloning vector, camR |

Epicentre® |

| Illumina® | ||

| pCC1.3 |

pCC1-based plasmid containing kanR marker, camRkanR |

[31] |

| pRB.TatA.5 |

Contains 886-nt insert specifying O35E tatA in pCC1, camR |

This study |

| pRB.TatB.1 |

Contains 858-nt insert specifying O35E tatB in pCC1, camR |

This study |

| pRB.TatC.2 |

Contains 1,018-nt insert specifying O12E tatC in pCC1, camR |

This study |

| pRB.TatC:kan |

pRB.TatC.2 in which a kanR marker disrupts the tatC ORF, camR kanR |

This study |

| pRB.Tat.1 |

Contains 2,083-nt insert specifying O35E tatABC locus in pCC1, camR |

This study |

| pRB.TatA:kan |

pRB.Tat.1 in which a kanR marker disrupts the tatA ORF, camR kanR |

This study |

| pRB.TatB:kan |

pRB.Tat.1 in which a kanR marker disrupts the tatB ORF, camR kanR |

This study |

| pRN.Bro11 |

Contains 994-nt insert specifying O35E bro-2 in pCC1, camR |

This study |

| pRB.Bro:kan |

pRN.Bro11 in which a kanR marker disrupts the bro-2 ORF, camR kanR |

This study |

| pTS.BroKK.Ec |

pRN.Bro11 in which 2 arginines in the signal sequence of the bro-2 gene product were replaced with 2 lysines by site-directed mutagenesis, camR |

This study |

| pWW115 |

M. catarrhalis-H. influenzae shuttle cloning vector, spcR |

[95] |

| pRB.TatA |

pWW115 into which the tatA insert of pRB.TatA.5 was subcloned, spcR |

This study |

| pRB.TatB |

pWW115 into which the tatB insert of pRB.TatB.1 was subcloned, spcR |

This study |

| pRB.TatC |

pWW115 into which the tatB insert of pRB.TatC.2 was subcloned, spcR |

This study |

| pRB.TAT |

pWW115 into which the tatABC locus of pRB.Tat.1 was subcloned, spcR |

This study |

| pTS.Bro |

pWW115 into which the bro-2 insert of pRN.Bro11 was subcloned, spcR |

This study |

| pTS.BroKK | pWW115 into which the bro-2 insert of pTS.BroKK.Ec was subcloned, spcR | This study |

Recombinant DNA techniques

Standard molecular biology techniques were performed as described elsewhere [97]. Moraxella catarrhalis genomic DNA was obtained using the Easy-DNA™ kit (Invitrogen™ Life Technologies™) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasmid DNA was purified with the QIAprep Spin Miniprep system (QIAGEN).

Polymerase chain reactions were performed using Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen™ Life Technologies™) unless otherwise specified. A 1,018-nt fragment containing the tatC gene was amplified with primers P1 (5′- AAAGCCAAGCCAACGGACTT-3′) and P2 (5′-ACCTCCAAGAAACCCACGCTATCA-3′) using genomic DNA from M. catarrhalis strain O12E (see Figure 1 for more details regarding primers). This PCR product was cloned into the vector pCC1 using the Copy Control™ PCR Cloning Kit (Epicentre® Illumina®) per the manufacturer’s instructions. This process yielded plasmid pRB.TatC.2, which was sequenced to verify that mutations were not introduced in the tatC gene during cloning. PCR products comprising tatA (886-nt in length), tatB (858-nt in length) and the entire tatABC locus (2,083-nt in length) were amplified with primers P3 (5′-AGGGCAACTGGCAAATTACCAACC-3′) and P4 (5′-AAACATGCCATACCATCGCCCAAG-3′), P5 (5′-CAAAGACTTGGGCAGTGCGGTAAA-3′) and P6 (5′-ATTCATTGGGCAGTAGAGCGACCA-3), and P7 (5′-CATCATTGCGGCCAAAGAGCTTGA-3′) and P8 (5′-AGCTTGCCGATCCAAACAGCTTTC-3′), respectively, using genomic DNA from M. catarrhalis strain O35E (see Figure 1 for more details regarding primers). These amplicons were cloned in the vector pCC1 as described above, producing plasmids pRB.TatA.5, pRB.TatB.1, and pRB.Tat.1. These constructs were sequenced to verify that mutations were not introduced in the tat genes during PCR. To examine conservation of the TatABC gene products, genomic DNA from M. catarrhalis strains O35E, O12E, McGHS1, V1171, and TTA37 was used to amplify 2.1-kb DNA fragments containing the entire tatABC locus with primer P7 and P8. These amplicons were sequenced in their entirety and the sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers HQ906880 (O35E), HQ906881 (O12E), HQ906882 (McGHS1), HQ906883 (V1171), and HQ906884 (TTA37).

The bro-2 gene specifying the β-lactamase of M. catarrhalis strain O35E was amplified with primers P9 (5′-TAATGATGCAACGCCGTCAT-3′) and P10 (5′-GCTTGTTGGGTCATAAATTTCC-3′) using Platinum® Pfx DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen™ Life Technologies™). This 994-nt PCR product was cloned into pCC1 as described above, generating the construct pRN.Bro11. Upon sequencing, the bro-2 gene contained by pRN.Bro11 was found to be free of mutation. The nucleotide sequence of O35E bro-2 was deposited in GenBank under the accession number JF279451.

Mutant construction

To create a tatC mutation in M. catarrhalis, the plasmid pRB.TatC.2 was mutagenized with the EZ-TN5™ < KAN-2 > Insertion Kit (Epicentre® Illumina®) and introduced into Transformax™ EPI300™ electrocompetent cells. Chloramphenicol resistant (camR, specified by the vector pCC1) and kanamycin resistant (kanR, specified by the EZ-TN5 < KAN-2 > TN) colonies were selected and plasmids were analyzed by PCR using the pCC1-specific primer, P11 (5′-TACGCCAAGCTATTTAGGTGAGA-3′), and primers specific for the kanR marker, P12 (5′-ACCTACAACAAAGCTCTCATCAACC-3′) and P13 (5′-GCAATGTAACATCAGAGATTTTGAG-3′). This strategy identified plasmid pRB.TatC:kan, in which the EZ-TN5 < KAN-2 > TN was inserted near the middle of the tatC ORF. The disrupted tatC gene was then amplified from pRB.TatC:kan with the pCC1-specific primers P11 and P14 (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′) using Platinum® Pfx DNA Polymerase. This 2.3-kb PCR product was purified and electroporated into M. catarrhalis strains O12E and O35E to create the kanR isogenic mutant strains O12E.TC and O35E.TC via homologous recombination. Allelic replacement was confirmed by PCR with the tatC primers P1 and P2 using Platinum® Pfx DNA Polymerase. These primers yielded PCR products in the mutant strains that were 1.2-kb larger than the amplicons obtained in the wild-type (WT) isolates O35E and O12E due to the presence of the EZ-TN5 < KAN-2 > TN in tatC.

To construct mutations in the tatA and tatB genes of M. catarrhalis O35E, the plasmid pRB.Tat.1 was first mutagenized with the EZ-TN5™ In-Frame Linker Insertion Kit (Epicentre® Illumina®) and introduced into Transformax™ EPI300™ electrocompetent cells. Plasmid DNA was isolated from several camR (specified by the vector pCC1) and kanR (specified by the EZ-TN5 < Not I/KAN-3 > TN) clones and sequenced to determine the sites of insertion of the TN. This approach identified the plasmids pRB.TatA:kan and pRB.TatB:kan, which contained the EZ-TN5 < Not I/KAN-3 > TN at nt 90 of the tatA ORF and nt 285 of the tatB ORF, respectively. These plasmids were then introduced into M. catarrhalis strain O35E by natural transformation as previously described [34]. The resulting kanR strains were screened by PCR using primers specific for tatA (P3 and P4) and tatB (P5 and P6), which produced DNA fragments that were 1.2-kb larger in size in mutant strains when compared to the WT strain O35E because of the insertion of the EZ-TN5 < Not I/KAN-3 > TN in tatA and tatB. This strategy yielded the mutant strains O35E.TA and O35E.TB.

To construct a mutation in the bro-2 gene of M. catarrhalis O35E, plasmid pRN.Bro11 was mutagenized with the EZ-TN5™ In-Frame Linker Insertion Kit as described above. Plasmids were isolated from kanR camR colonies and sequenced to identify constructs containing the EZ-TN5 < Not I/KAN-3 > TN near the middle of the bro-2 ORF. This approach yielded the construct pRB.Bro:kan, which was introduced in M. catarrhalis O35E by natural transformation. Transformants were selected for resistance to kanamycin and then tested for their ability to grow on agar plates containing the β-lactam antibiotic carbenicillin. KanR and carbenicillin sensitive (cabS) strains were further analyzed by PCR using primers P9 and P10 to verify allelic exchange of the bro-2 gene. These primers produced a 1-kb DNA fragment in the WT strain O35E and a 2.2-kb in the mutant O35E.Bro, which is consistent with insertion of the 1.2-kb EZ-TN5 < Not I/KAN-3 > TN in bro-2.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the M. catarrhalis bro-2 gene

The bro-2 ORF of M. catarrhalis O35E harbored by plasmid pRN.Bro11 was mutated using the QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mutagenesis primers, P15 (5′- AAGGGGATAATGATGCAAAAGAAGCATTTTTTA-3′) and P16 (5′-GGTTTTTTGTAAAAAATGCTTCTTTTGCAT CAT-3′), were used to replace two arginine residues at position 4 and 5 of BRO-2 with two lysines, yielding plasmid pTS.BroKK.Ec. This plasmid was sequenced to verify that only the intended mutations were introduced in the bro-2 ORF.

Complementation of mutants

The construction of plasmids to complement tat and bro2 mutant strains was achieved as follows. Plasmid DNA (pRB.TatA.5, pRB.TatB.1, pRB.TatC.2, pRB.Tat.1, pRN.Bro11, pTS.BroKK.Ec) was digested with BamHI to release the cloned M. catarrhalis genes from the vector pCC1. Gene fragments were purified from agarose gel slices using the High Pure PCR Product Purification Kit (Roche Applied Science), ligated into the BamHI site of the M. catarrhalis/Haemophilus influenza-compatible shuttle vector pWW115 [95], and electroporated into H. influenzae strain DB117. Spectinomycin resistant (spcR) colonies were screened by PCR using the pWW115-specific primers P17 (5′-TACGCCCTTTTATACTGTAG-3′) and P18 (5′-AACGACAGGAGCACGATCAT-3′), which flank the BamHI cloning site, to identify clones containing inserts of the appropriate size for the tat and bro2 genes. This process produced plasmids pRB.TatA, pRB.TatB, pRB.TatC, pRB.TAT, pTS.Bro, and pTS.BroKK. The O35E.TA mutant was naturally transformed with plasmids pWW115, pRB.TatA, and pRB.TatABC. The plasmids pWW115, pRB.TatB, and pRB.TAT were introduced in the O35E.TB mutant by natural transformation. The tatC mutants O35E.TC and O12E.TC were naturally transformed with the vector pWW115 and plasmid pRB.TatC. The plasmids pWW115, pTS.Bro, and pTS.BroKK were electroporated into the bro-2 mutant strain O35E.Bro. The successful introduction of these plasmids into the indicated strains was verified by PCR analysis of spcR transformants with the pWW115-specific primers P17 and P18, and by restriction endonuclease analysis of plasmid DNA purified from each strain.

Growth rate experiments

Moraxella. catarrhalis strains were first cultured onto agar plates supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. These plate-grown bacteria were used to inoculate 500-mL sidearm flasks containing 20-mL of broth (without antibiotics) to an optical density (OD) of 50 Klett units. The cultures were then incubated with shaking (225-rpm) at a temperature of 37°C for 7-hr. The OD of each culture was determined every 60-min using a Klett™ Colorimeter (Scienceware®). These experiments were repeated on at least three separate occasions for each strain. In some experiments, aliquots were taken out of each culture after recording the optical density, diluted, and spread onto agar plates to determine the number of viable colony forming units (CFU).

Carbenicillin sensitivity assays

Moraxella catarrhalis strains were first cultured onto agar plates supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics. These plate-grown bacteria were used to inoculate sterile Klett tubes containing five-mL of broth (without antibiotics) to an OD of 40 Klett units. Portions of these suspensions (25 μL) were spotted onto agar medium without antibiotics as well on plates supplemented with carbenicillin, and incubated at 37°C for 48-hr to evaluate growth. Each strain was tested in this manner a minimum of three times.

Nitrocefin assays

Moraxella catarrhalis and H. influenzae strains were tested for their ability to cleave the chromogenic β-lactamase substrate nitrocefin as previously described [98]. Bacterial strains were first cultured onto agar plates supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. These plate-grown cells were suspended to an OD of 300 Klett units in 5-mL of broth, and aliquots (50 μL, ~107 CFU) were transferred to duplicate wells of a 48-well tissue culture plate; control wells were seeded with broth only. To each of these wells, 325 μL of a nitrocefin (Calbiochem®) solution (250 μg/mL in phosphate buffer) was added and the absorbance at a wavelength of 486 nm (A486) was immediately measured using a μQuant™ Microplate Spectrophotometer (BioTek®) and recorded as time “0”. The A486 of the samples was then measured after a 30-min incubation at room temperature. These experiments were repeated a minimum of three times for each strain.

Sequence analyses and TAT prediction Programs

Sequencing results were analyzed and assembled using Sequencher® 4.9 (Gene Codes Corporation). Sequence analyses and comparisons were performed using the various tools available through the ExPASy Proteomics Server (http://au.expasy.org/) and NCBI (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). To identify potential TAT substrates of M. catarrhalis, annotated nucleotide sequences from strain ATCC43617 [81] were translated and analyzed with the prediction algorithms available through the TatFind 1.4 (http://signalfind.org/tatfind.html) [82] and TatP 1.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TatP/) [83] servers using the default settings. The published genomic sequence of M. catarrhalis strain BBH18 [78] was analyzed in the same manner.

Statistical analyses

The GraphPad Prism Software was used for all statistical analyses. Growth rate experiments and nitrocefin assays were analyzed by a two-way analysis of variants (ANOVA), followed by the Bonferroni post-test of the means of each time point. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences where P < 0.05.

Abbreviations

ORF: Open reading frame; kanR: Kanamycin-resistance; spcR: Spectinomycin-resistance; camR: Chloramphenicol-resistance; cabR: Carbenicillin-resistance; cabS: Carbenicillin-sensitive; A486: Absorbance at a wavelength of 486 nm, TAT, twin-arginine translocation; MW: Molecular weight; CFU: Colony forming units; OD: Optical density; aa: Amino acid.

Competing interests

RB, TLS and ERL do not have financial or non-financial competing interests. In the past five years, the authors have not received reimbursements, fees, funding, or salary from an organization that may in any way gain or lose financially from the publication of this manuscript, either now or in the future. Such an organization is not financing this manuscript. The authors do not hold stocks or shares in an organization that may in any way gain or lose financially from the publication of this manuscript, either now or in the future. The authors do not hold and are not currently applying for any patents relating to the content of the manuscript. The authors have not received reimbursements, fees, funding, or salary from an organization that holds or has applied for patents relating to the content of the manuscript. The authors do not have non-financial competing interests (political, personal, religious, ideological, academic, intellectual, commercial or any other) to declare in relation to this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

RB helped conceive the study, participated in its design and coordination, performed most of the experiments, and helped with redaction of the manuscript. TLS performed the experiments pertaining to site-directed mutagenesis of bro-2 and functional analysis of the mutated gene product. ERL conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped with redaction of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Rachel Balder, Email: rachel.balder@gmail.com.

Teresa L Shaffer, Email: ts314@uga.edu.

Eric R Lafontaine, Email: elafon10@uga.edu.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from NIH/NIAID (AI051477) and startup funds from the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine to ERL.

References

- Cripps AW, Otczyk DC, Kyd JM. Bacterial otitis media: a vaccine preventable disease? Vaccine. 2005;23(17–18):2304–2310. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebink GS, Kurono Y, Bakaletz LO, Kyd JM, Barenkamp SJ, Murphy TF, Green B, Ogra PL, Gu XX, Patel JA. et al. Recent advances in otitis media. 6. Vaccine. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 2005;194:86–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karalus R, Campagnari A. Moraxella catarrhalis: a review of an important human mucosal pathogen. Microbes Infect. 2000;2(5):547–559. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)00314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TF. Vaccine development for non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis: progress and challenges. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2005;4(6):843–853. doi: 10.1586/14760584.4.6.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichichero ME, Casey JR. Otitis media. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2002;3(8):1073–1090. doi: 10.1517/14656566.3.8.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verduin CM, Hol C, Fleer A, van Dijk H, van Belkum A. Moraxella catarrhalis: from emerging to established pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15(1):125–144. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.1.125-144.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden H. The microbiologic and immunologic basis for recurrent otitis media in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160(7):407–413. doi: 10.1007/s004310100754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright MC, McKenzie H. Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis–clinical and molecular aspects of a rediscovered pathogen. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46(5):360–371. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-5-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arguedas A, Kvaerner K, Liese J, Schilder AG, Pelton SI. Otitis media across nine countries: disease burden and management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(12):1419–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subcommittee on Management of Acute Otitis Media. Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1451–1465. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Beccaro MA, Mendelman PM, Inglis AF, Richardson MA, Duncan NO, Clausen CR, Stull TL. Bacteriology of acute otitis media: a new perspective. J Pediatr. 1992;120(1):81–84. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)80605-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden H, Duffy L, Wasielewski R, Wolf J, Krystofik D, Tung Y. Relationship between nasopharyngeal colonization and the development of otitis media in children. Tonawanda/Williamsville Pediatrics. J Infect Dis. 1997;175(6):1440–1445. doi: 10.1086/516477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden H, Stanievich J, Brodsky L, Bernstein J, Ogra PL. Changes in nasopharyngeal flora during otitis media of childhood. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9(9):623–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruuskanen O, Heikkinen T. Otitis media: etiology and diagnosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13(1 Suppl 1):S23–S26. discussion S50-S54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stool SE, Field MJ. The impact of otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8(1 Suppl):S11–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein JO. Otitis media. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19(5):823–833. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.5.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein JO. The burden of otitis media. Vaccine. 2000;19(Suppl 1):S2–S8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein JO, Teele DW, Pelton SI. New concepts in otitis media: results of investigations of the Greater Boston Otitis Media Study Group. Adv Pediatr. 1992;39:127–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TF. Branhamella catarrhalis: epidemiology, surface antigenic structure, and immune response. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60(2):267–279. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.267-279.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TF, Brauer AL, Grant BJ, Sethi S. Moraxella catarrhalis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: burden of disease and immune response. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(2):195–199. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1747OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethi S, Evans N, Grant BJ, Murphy TF. New strains of bacteria and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(7):465–471. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethi S, Murphy TF. Bacterial Infection in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in 2000: a State-of-the-Art Review. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14(2):336–363. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.2.336-363.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (NHLBI) NIoH. Morbidity and Mortality: 2009 Chart Book on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Diseases. 2009. http://wwwnhlbinihgov/resources/docs/2009_ChartBookpdf.

- Strassels SA, Smith DH, Sullivan SD, Mahajan PS. The costs of treating COPD in the United States. Chest. 2001;119(2):344–352. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan SD, Ramsey SD, Lee TA. The economic burden of COPD. Chest. 2000;117(2 Suppl):5S–9S. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.2_suppl.5s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter MH, King DE. COPD: management of acute exacerbations and chronic stable disease. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(4):603–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd S. The impact of COPD on lung health worldwide: epidemiology and incidence. Chest. 2000;117(2 Suppl):1S–4S. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.2_suppl.1s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafontaine ER, Cope LD, Aebi C, Latimer JL, McCracken GH Jr, Hansen EJ. The UspA1 protein and a second type of UspA2 protein mediate adherence of Moraxella catarrhalis to human epithelial cells in vitro. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(5):1364–1373. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.5.1364-1373.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipski SL, Akimana C, Timpe JM, Wooten RM, Lafontaine ER. The Moraxella catarrhalis autotransporter McaP is a conserved surface protein that mediates adherence to human epithelial cells through its N-terminal passenger domain. Infect Immun. 2007;75(1):314–324. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01330-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpe JM, Holm MM, Vanlerberg SL, Basrur V, Lafontaine ER. Identification of a Moraxella catarrhalis outer membrane protein exhibiting both adhesin and lipolytic activities. Infect Immun. 2003;71(8):4341–4350. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4341-4350.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm MM, Vanlerberg SL, Foley IM, Sledjeski DD, Lafontaine ER. The Moraxella catarrhalis porin-like outer membrane protein CD is an adhesin for human lung cells. Infect Immun. 2004;72(4):1906–1913. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.1906-1913.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balder R, Krunkosky TM, Nguyen CQ, Feezel L, Lafontaine ER. Hag mediates adherence of Moraxella catarrhalis to ciliated human airway cells. Infect Immun. 2009;77(10):4597–4608. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00212-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullard B, Lipski SL, Lafontaine ER. Hag directly mediates the adherence of Moraxella catarrhalis to human middle ear cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73(8):5127–5136. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.5127-5136.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balder R, Hassel J, Lipski S, Lafontaine ER. Moraxella catarrhalis strain O35E expresses two filamentous hemagglutinin-like proteins that mediate adherence to human epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2007;75(6):2765–2775. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00079-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plamondon P, Luke NR, Campagnari AA. Identification of a novel two-partner secretion locus in Moraxella catarrhalis. Infect Immun. 2007;75(6):2929–2936. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00396-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke NR, Jurcisek JA, Bakaletz LO, Campagnari AA. Contribution of Moraxella catarrhalis type IV pili to nasopharyngeal colonization and biofilm formation. Infect Immun. 2007;75(12):5559–5564. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00946-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng D, Hu WG, Choudhury BP, Muszynski A, Carlson RW, Gu XX. Role of different moieties from the lipooligosaccharide molecule in biological activities of the Moraxella catarrhalis outer membrane. FEBS J. 2007;274(20):5350–5359. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attia AS, Ram S, Rice PA, Hansen EJ. Binding of vitronectin by the Moraxella catarrhalis UspA2 protein interferes with late stages of the complement cascade. Infect Immun. 2006;74(3):1597–1611. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1597-1611.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallstrom T, Nordstrom T, Tan TT, Manolov T, Lambris JD, Isenman DE, Zipfel PF, Blom AM, Riesbeck K. Immune evasion of Moraxella catarrhalis involves ubiquitous surface protein A-dependent C3d binding. J Immunol. 2011;186(5):3120–3129. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom T, Blom AM, Forsgren A, Riesbeck K. The emerging pathogen Moraxella catarrhalis interacts with complement inhibitor C4b binding protein through ubiquitous surface proteins A1 and A2. J Immunol. 2004;173(7):4598–4606. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom T, Blom AM, Tan TT, Forsgren A, Riesbeck K. Ionic binding of C3 to the human pathogen Moraxella catarrhalis is a unique mechanism for combating innate immunity. J Immunol. 2005;175(6):3628–3636. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TF, Brauer AL, Yuskiw N, Hiltke TJ. Antigenic structure of outer membrane protein E of Moraxella catarrhalis and construction and characterization of mutants. Infect Immun. 2000;68(11):6250–6256. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.11.6250-6256.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helminen ME, Maciver I, Paris M, Latimer JL, Lumbley SL, Cope LD, McCracken GH Jr, Hansen EJ. A mutation affecting expression of a major outer membrane protein of Moraxella catarrhalis alters serum resistance and survival in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1993;168(5):1194–1201. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.5.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs MR, Bajaksouzian S, Windau A, Good CE, Lin G, Pankuch GA, Appelbaum PC. Susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis to 17 oral antimicrobial agents based on pharmacodynamic parameters: 1998–2001 U S Surveillance Study. Clin Lab Med. 2004;24(2):503–530. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klugman KP. The clinical relevance of in-vitro resistance to penicillin, ampicillin, amoxycillin and alternative agents, for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38(Suppl A):133–140. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.suppl_A.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manninen R, Huovinen P, Nissinen A. Increasing antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis in Finland. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40(3):387–392. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter SS, Winokur PL, Brueggemann AB, Huynh HK, Rhomberg PR, Wingert EM, Doern GV. Molecular characterization of the beta-lactamases from clinical isolates of Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis obtained from 24 U.S. medical centers during 1994–1995 and 1997–1998. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(2):444–446. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.2.444-446.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadry AA, Fouda SI, Elkhizzi NA, Shibl AM. Correlation between susceptibility and BRO type enzyme of Moraxella catarrhalis strains. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;22(5):532–536. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(03)00158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz FJ, Beeck A, Perdikouli M, Boos M, Mayer S, Scheuring S, Kohrer K, Verhoef J, Fluit AC. Production of BRO beta-lactamases and resistance to complement in European Moraxella catarrhalis isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(4):1546–1548. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.4.1546-1548.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DM, Sader HS, Fritsche TR, Biedenbach DJ, Jones RN. Susceptibility trends of haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis against orally administered antimicrobial agents: five-year report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;47(1):373–376. doi: 10.1016/S0732-8893(03)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esel D, Ay-Altintop Y, Yagmur G, Gokahmetoglu S, Sumerkan B. Evaluation of susceptibility patterns and BRO beta-lactamase types among clinical isolates of Moraxella catarrhalis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13(10):1023–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootsma HJ, Aerts PC, Posthuma G, Harmsen T, Verhoef J, van Dijk H, Mooi FR. Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis BRO beta-lactamase: a lipoprotein of gram-positive origin? J Bacteriol. 1999;181(16):5090–5093. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.5090-5093.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootsma HJ, van Dijk H, Vauterin P, Verhoef J, Mooi FR. Genesis of BRO beta-lactamase-producing Moraxella catarrhalis: evidence for transformation-mediated horizontal transfer. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36(1):93–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torretta S, Drago L, Marchisio P, Gaffuri M, Clemente IA, Pignataro L. Topographic distribution of biofilm-producing bacteria in adenoid subsites of children with chronic or recurrent middle ear infections. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2013;122(2):109–113. doi: 10.1177/000348941312200206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakaletz LO. Bacterial biofilms in the upper airway - evidence for role in pathology and implications for treatment of otitis media. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2012;13(3):154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster CE, Hong W, Pang B, Weimer KE, Juneau RA, Turner J, Swords WE. Indirect Pathogenicity of Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis in Polymicrobial Otitis Media Occurs via Interspecies Quorum Signaling. MBio. 2010;1(3):e00102–e00110. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00102-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoa M, Tomovic S, Nistico L, Hall-Stoodley L, Stoodley P, Sachdeva L, Berk R, Coticchia JM. Identification of adenoid biofilms with middle ear pathogens in otitis-prone children utilizing SEM and FISH. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(9):1242–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Stoodley L, Hu FZ, Gieseke A, Nistico L, Nguyen D, Hayes J, Forbes M, Greenberg DP, Dice B, Burrows A. et al. Direct detection of bacterial biofilms on the middle-ear mucosa of children with chronic otitis media. JAMA. 2006;296(2):202–211. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.2.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer T, Berks BC. The twin-arginine translocation (Tat) protein export pathway. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10(7):483–496. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent F. The twin-arginine transport system: moving folded proteins across membranes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35(Pt 5):835–847. doi: 10.1042/BST0350835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berks BC, Palmer T, Sargent F. Protein targeting by the bacterial twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8(2):174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammertyn E, Anne J. Protein secretion in Legionella pneumophila and its relation to virulence. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;238(2):273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, Wang Q, Sheng L, Liu Q, Zhang Y. Functional characterization of Vibrio alginolyticus twin-arginine translocation system: its roles in biofilm formation, extracellular protease activity, and virulence towards fish. Curr Microbiol. 2011;62(4):1193–1199. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9844-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truan D, Vasil A, Stonehouse M, Vasil ML, Pohl E. High-level over-expression, purification, and crystallization of a novel phospholipase C/sphingomyelinase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Protein Expr Purif. 2013;90(1):40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitkiewicz I, Stockbauer KE, Musser JM. Secreted bacterial phospholipase A2 enzymes: better living through phospholipolysis. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15(2):63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi ZY, Wang H, Gu L, Cui ZG, Wu LF, Kan B, Pang B, Wang X, Xu JG, Jing HQ. Pleiotropic effect of tatC mutation on metabolism of pathogen Yersinia enterocolitica. Biomed Environ Sci. 2007;20(6):445–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavander M, Ericsson SK, Broms JE, Forsberg A. Twin arginine translocation in Yersinia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;603:258–267. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72124-8_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldelari I, Mann S, Crooks C, Palmer T. The Tat pathway of the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae is required for optimal virulence. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19(2):200–212. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein PA, Marrichi M, Cartinhour S, Schneider DJ, DeLisa MP. Identification of a twin-arginine translocation system in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and its contribution to pathogenicity and fitness. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(24):8450–8461. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.24.8450-8461.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner UA, Snyder A, Vasil AI, Vasil ML. Effects of the twin-arginine translocase on secretion of virulence factors, stress response, and pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(12):8312–8317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082238299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltcher ME, Sullivan JT, Braunstein M. Protein export systems of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: novel targets for drug development? Future Microbiol. 2010;5(10):1581–1597. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough JA, McCann JR, Tekippe EM, Silverman JS, Rigel NW, Braunstein M. Identification of functional Tat signal sequences in Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(19):6428–6438. doi: 10.1128/JB.00749-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann JR, McDonough JA, Pavelka MS, Braunstein M. Beta-lactamase can function as a reporter of bacterial protein export during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of host cells. Microbiology. 2007;153(Pt 10):3350–3359. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/008516-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough JA, Hacker KE, Flores AR, Pavelka MS Jr, Braunstein M. The twin-arginine translocation pathway of Mycobacterium smegmatis is functional and required for the export of mycobacterial beta-lactamases. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(22):7667–7679. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.22.7667-7679.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkila MP, Honisch U, Wunsch P, Zumft WG. Role of the Tat ransport system in nitrous oxide reductase translocation and cytochrome cd1 biosynthesis in Pseudomonas stutzeri. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(5):1663–1671. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.5.1663-1671.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson LG, Strisovsky K, Clemmer KM, Bhatt S, Freeman M, Rather PN. Rhomboid protease AarA mediates quorum-sensing in Providencia stuartii by activating TatA of the twin-arginine translocase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(3):1003–1008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608140104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Hu B, Qian G, Wang C, Yang W, Han Z, Liu F. Identification and molecular characterization of twin-arginine translocation system (Tat) in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae strain PXO99. Arch Microbiol. 2009;191(2):163–170. doi: 10.1007/s00203-008-0440-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries SP, van Hijum SA, Schueler W, Riesbeck K, Hays JP, Hermans PW, Bootsma HJ. Genome analysis of Moraxella catarrhalis strain RH4, a human respiratory tract pathogen. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(14):3574–3583. doi: 10.1128/JB.00121-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley NR, Findlay K, Berks BC, Palmer T. Escherichia coli strains blocked in Tat-dependent protein export exhibit pleiotropic defects in the cell envelope. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(1):139–144. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.139-144.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Joanis B, Demangel C, Jackson M, Brodin P, Marsollier L, Boshoff H, Cole ST. Inactivation of Rv2525c, a substrate of the twin arginine translocation (Tat) system of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, increases beta-lactam susceptibility and virulence. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(18):6669–6679. doi: 10.1128/JB.00631-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Reitzer L, Rasko DA, Pearson MM, Blick RJ, Laurence C, Hansen EJ. Metabolic analysis of Moraxella catarrhalis and the effect of selected in vitro growth conditions on global gene expression. Infect Immun. 2007;75(10):4959–4971. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00073-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose RW, Bruser T, Kissinger JC, Pohlschroder M. Adaptation of protein secretion to extremely high-salt conditions by extensive use of the twin-arginine translocation pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45(4):943–950. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, Widdick D, Palmer T, Brunak S. Prediction of twin-arginine signal peptides. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:167. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm A, Schierhorn A, Lindenstrauss U, Lilie H, Bruser T. YcdB from Escherichia coli reveals a novel class of Tat-dependently translocated hemoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(20):13972–13978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511891200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bloois E, Torres Pazmino DE, Winter RT, Fraaije MW. A robust and extracellular heme-containing peroxidase from Thermobifida fusca as prototype of a bacterial peroxidase superfamily. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;86(5):1419–1430. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2369-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann J, Bauer B, Zwicker K, Ludwig B, Anderka O. The Rieske protein from Paracoccus denitrificans is inserted into the cytoplasmic membrane by the twin-arginine translocase. FEBS J. 2006;273(21):4817–4830. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders C, Wethkamp N, Lill H. Transport of cytochrome c derivatives by the bacterial Tat protein translocation system. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41(1):241–246. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb DC, Rosenberg H, Cox GB. Mutational analysis of the Escherichia coli phosphate-specific transport system, a member of the traffic ATPase (or ABC) family of membrane transporters. A role for proline residues in transmembrane helices. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(34):24661–24668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy A, McGrath J, Cripps AW, Kyd JM. The incidence of Streptococcus pneumoniae otitis media is affected by the polymicrobial environment particularly Moraxella catarrhalis in a mouse nasal colonisation model. Microbes Infect. 2009;11(5):545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darabi A, Hocquet D, Dowzicky MJ. Antimicrobial activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae collected globally between 2004 and 2008 as part of the Tigecycline Evaluation and Surveillance Trial. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;67(1):78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaar V, Nordstrom T, Morgelin M, Riesbeck K. Moraxella catarrhalis outer membrane vesicles carry beta-lactamase and promote survival of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae by inactivating amoxicillin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(8):3845–3853. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01772-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasil ML, Tomaras AP, Pritchard AE. Identification and evaluation of twin-arginine translocase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(12):6223–6234. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01575-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm MM, Vanlerberg SL, Sledjeski DD, Lafontaine ER. The Hag protein of Moraxella catarrhalis strain O35E is associated with adherence to human lung and middle ear cells. Infect Immun. 2003;71(9):4977–4984. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.4977-4984.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aebi C, Lafontaine ER, Cope LD, Latimer JL, Lumbley SL, McCracken GH Jr, Hansen EJ. Phenotypic effect of isogenic uspA1 and uspA2 mutations on Moraxella catarrhalis 035E. Infect Immun. 1998;66(7):3113–3119. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3113-3119.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Hansen EJ. Plasmid pWW115, a cloning vector for use with Moraxella catarrhalis. Plasmid. 2006;56(2):133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow JK, Brown DC, Boling ME, Mattingly A, Gordon MP. Repair of deoxyribonucleic acid in Haemophilus influenzae. I. X-ray sensitivity of ultraviolet-sensitive mutants and their behavior as hosts to ultraviolet-irradiated bacteriophage and transforming deoxyribonucleic acid. J Bacteriol. 1968;95(2):546–558. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.2.546-558.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Third. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MM, Hansen EJ. Identification of Gene Products Involved in Biofilm Production by Moraxella catarrhalis ETSU-9 In Vitro. Infect Immun. 2007;75(9):4316–4325. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01347-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]