Abstract

Purpose

Vitamin C is an antioxidant vitamin that has been hypothesized to antagonize the effects of reactive oxygen species-generating antineoplastic drugs.

Experimental Design

The therapeutic efficacy of the widely-used antineoplastic drugs, doxorubicin, cisplatin, vincristine, methotrexate and imatinib were compared in leukemia (K562) and lymphoma (RL) cell lines with and without pre-treatment with dehydroascorbic acid, the commonly transported form of vitamin C. The impact of vitamin C on viability, clonogenicity, apoptosis, P-glycoprotein, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mitochondrial membrane potential was determined.

Results

Pre-treatment with vitamin C caused a dose-dependent attenuation of cytotoxicity as measured by trypan blue exclusion and colony formation after treatment with all anti-neoplastic agents tested. Vitamin C administered prior to doxorubicin treatment led to a substantial reduction of therapeutic efficacy in mice with RL cell-derived xenogeneic tumors. Vitamin C treatment led to a dose-dependent decrease in apoptosis in cells treated with the antineoplastic agents that was not due to up-regulation of P-glycoprotein or vitamin C retention modulated by anti-neoplastics. Vitamin C had only modest effects on intracellular ROS and a more general cytoprotective profile than N-acetylcysteine; suggesting a mechanism of action that is not mediated by ROS. All antineoplastic agents tested caused mitochondrial membrane depolarization that was inhibited by vitamin C.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that vitamin C administered prior to mechanistically dissimilar antineoplastic agents antagonizes therapeutic efficacy in a model of human hematopoietic cancers by preserving mitochondrial membrane potential. These results support the hypothesis that vitamin C supplementation during cancer treatment may detrimentally affect therapeutic response.

Keywords: cancer, reactive oxygen species, mitochondria, apoptosis

INTRODUCTION

The effects of vitamin C on cancer and its treatment are controversial (1, 2). Clinical studies suggesting a therapeutic benefit of vitamin C supplementation in patients with cancer have not been consistently reproducible (2, 3). Nonetheless, vitamin C, predominantly in the form of ascorbic acid, remains a commonly used nutritional supplement and the influence of vitamin C on the action of agents used in treating cancer is unknown. Some antineoplastic agents such as cisplatin and doxorubicin lead to increases in intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) that may contribute to their therapeutic effect (4, 5). Vitamin C is a potent antioxidant, raising the theoretical concern that vitamin C supplementation might attenuate the antineoplastic activity of drugs that lead to increased ROS (2). Conversely, some reports have suggested that vitamin C might potentiate the effects of some antineoplastic agents, such as arsenic trioxide (6, 7). In the case of arsenic trioxide, however, the enhanced cytotoxicity by vitamin C may be due to the extracellular generation of hydrogen peroxide and increased intracellular concentrations of vitamin C appear to attenuate the cytotoxic effects of arsenic (8).

Ascorbic acid (AA) and dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) are the principle physiologic chemical forms of vitamin C. While AA is present in much higher concentrations in the serum, intracellular transport is restricted to a limited number of tissues(9). In contrast, DHA, the oxidized form of vitamin C, enters cells via facilitated transport through the glucose transporters, primarily GLUT1, and has a substantially wider distribution (10, 11). After transport, DHA is reduced to AA and is trapped intracellularly (10, 11). This mechanism leads to rapid and durable accumulation of high concentrations of intracellular ascorbic acid. In the cell, AA and other intracellular antioxidants such as glutathione serve to mitigate the effects of ROS, function as important biochemical substrates, and are the first antioxidants consumed in conditions of elevated ROS(12–14). Ascorbate is also an electron donor for eight different enzymes and thereby plays an important role in a wide variety of biochemical processes, including collagen formation (15), norepinephrine biosynthesis (16) and mitochondrial fatty acid transport (17). The mitochondria, in particular, generate ROS as byproducts of respiration making the simpler architecture of mitochondrial DNA and mitochondrial proteins particularly susceptible to oxidative damage. Vitamin C may, thus, play an important role in protecting the mitochondria and mitochondrial translation products from ROS (18, 19).

To ascertain the influence of vitamin C on the cytotoxicity of antineoplastic agents, we used DHA to increase intracellular concentrations of vitamin C. When intracellular vitamin C levels were increased in the myeloblastic chronic myeloid leukemia cell line, K562, and the lymphoma cell line, RL, as well as in mice with RL cell xenografts, the cells and tumors were more resistant to the therapeutic effects of anticancer drugs that exert their cytotoxic effects through increased ROS, as well as antineoplastic agents that do not appreciably affect ROS. Treatment with all of the antineoplastic agents tested led to mitochondrial membrane depolarization. Pretreatment with vitamin C substantially attenuated the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, suggesting a mitochondrial site of action.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

K562 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in RPMI containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA), 25 mM HEPES and 2 mM L-glutamine (both Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RL cells (American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in RPMI containing 20% FBS, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 4.5 g/L glucose, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate with pen/strep and L-glutamine as above.

Vitamin C loading and intracellular concentration determination

Cellular ascorbic acid uptake was determined as described previously(20). Briefly, cells were added to incubation buffer containing 3:1 L-ascorbic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO):L-[14C]ascorbic acid (4mCi/mmol, PerkinElmer, Wellesley, MA) and supplemented with 20 μM dithiothreitol (Sigma) to achieve final concentrations of 0–750 μM AA and 20 μM DTT. DHA was generated by preincubation of AA for 5 minutes with ascorbate oxidase (Sigma) at 20 U/μmol L-ascorbate. After incubation for 1 hour at 37°C, cell pellets were washed three times by centrifugation at 600g in cold PBS, lysed and the incorporated radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry. Intracellular volume was estimated by incubating cells with [3H] oxy-methyl-glucose as described previously(10, 11), applying a 30% correction for trapped extracytosolic radioactivity (21). Experiments measuring ascorbic acid retention utilized the same DHA loading method cited above and scintillation spectrometry was performed on cell pellets washed three times by centrifugation at 600g in cold PBS at each time point after the addition of antineoplastic agents. Residual ascorbate oxidase does not influence DHA uptake(22). Vitamin C uptake was analyzed using non-linear regression analysis with GraphPad Prism 5.0a for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Effects of vitamin C and N-acetylcysteine on cell growth and viability

RL and K562 cells were incubated with 0–500 μM DHA for 1 hour to achieve intracellular concentrations between 0 mM-9 mM and 0 mM-18 mM ascorbic acid respectively. Following loading, cell pellets were washed three times in PBS and resuspended in media supplemented with antineoplastic agents at IC75 concentrations and cultured for up to 48 hours. In experiments with N-acetylcysteine, 25 mM N-acetylcysteine (American Regent, Shirley, NY) was added with the antineoplastic agents and remained in culture throughout the course of exposure. Cellular viability was determined by Trypan blue exclusion. For colony assays cells were treated with DHA to achieve high intracellular vitamin C concentrations (K562 [AA]=18mm, and RL [AA]=8.5mM) and then treated for 48 hours with antineoplastic agents, washed three times in PBS and resuspended at equal densities in MethoCult™ H4100 (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). Plates were assessed at 14 days for colonies of 50 cells or greater. The measured IC75 concentrations are as follows: vincristine sulfate (GensiaSicor Pharma, Irvine, CA)-500 nM, doxorubicin HCl (Bedford Labs, Bedford, OH)-600 nM, methotrexate (Xanodyne Pharmacal, Newport, KY)-100 μM, cisplatin (Bristol Labs, New York, NY)-200 μM, imatinib mesylate (kindly provided by Dr. William Bornmann)-2.25 μM, and actinonin (Sigma) - 52 μM.

Animals

FOX CHASE SCID™ ICR mice (Taconic, Germantown, NY) were grafted with 1×107 RL cells, via subcutaneous injection to the right flank. Following the development of palpable tumor (2 mm × 2 mm minimum 14 days post engraftment) animals were divided into cohorts (n=5) and treated on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 14, 16, 26 and 28 with vehicle, vitamin C (250 mg/kg DHA) by tail vein, doxorubicin (1 mg/kg) intraperitoneally or vitamin C and doxorubicin by the same route of administration and at the same doses. DHA for injection was generated by incubation of ascorbic acid with ascorbate oxidase (23, 24). Animals with tumors more than 2000 mm3 were euthanized, so few animals treated with vehicle or vitamin C alone were carried beyond 18 days after treatment induction. Any animals that showed signs of toxicity, either through visual inspection or as measured by weight loss (>10%), were treated with 100 μL normal saline, subcutaneously, until weight returned to pretreatment levels. All animal procedures were done in accordance with the guidelines of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Following final tumor dimension measurements, intratumor vitamin C concentrations were determined 2 hours after injection of DHA on day 32 by HPLC-ECD with an ESA CoulArray system (ESA, Chelmsford, MA) equipped with a modified C18 column (Phenomenex, Sutter Creek, CA). Doxorubicin levels were determined on the tumors of 3 mice taken from each cohort on day 32, 4 days after the last doxorubicin administration (32). Tumor samples for vitamin C and doxorubicin levels were stored at −80°C.

Fluorometric assays

TUNEL reaction mixture (TUNEL enzyme and TUNEL label, Roche, Nutley, NJ) was added to cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were preloaded with vitamin C as above, and treated for 48 hours with antineoplastic agents at IC75 concentrations. P-glycoprotein detection was performed by blocking non-specific binding with heat inactivated human serum and subsequent treatment of 1×106 cells with U1C2-A488 (Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated hu-P-glycoprotein AB, MSKCC Monoclonal Antibody Core Facility) 100 μg/mL in PBS, for 1 hour, on ice and in the dark. Cells were then washed and re-suspended in PBS + 0.5% paraformaldehyde for data acquisition. To determine intracellular ROS, cells were washed in Krebs Ringer solution, incubated with 0.1 μg/mL CM-H2DCFDA (16) (Invitrogen) for 15 minutes at 37°C and immediately placed on ice until assayed. For the detection of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ m), cells were incubated with 10 μg/mL JC-1 (Invitrogen) for 5 minutes at 37°. Cells were washed three times in PBS, resuspended in normal growth media and incubated under normal growth conditions for 1 hour before being loaded with vitamin C. After loading, cells were exposed to antineoplastic agents at IC75 concentrations in media for 6 hours at 37°C. All flow cytometric acquisitions were performed on a BD FACSCalibur system (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with data analysis performed using FlowJo analysis software, version 6.0 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

RESULTS

RL and K562 cells take up only DHA

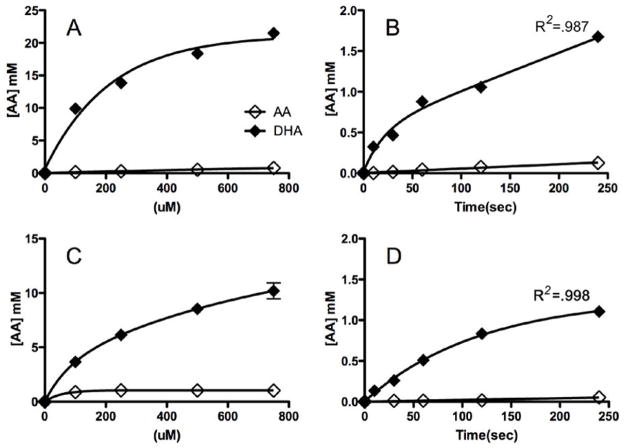

Two cell lines, (RL, derived from a patient with transformed B-cell follicular lymphoma, and K562, derived from a patient with myeloblastic chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML)) were treated with DHA and AA (Figure 1). As has been noted in other hematopoietic cell lines (8, 11) only DHA and not AA was taken up by K562 and RL cells to any appreciable extent. In each case, the cells accumulated substantial intracellular concentrations of AA in a dose dependent manner, achieving intracellular AA concentrations up to 8.5 mM in RL and 18 mM in K562 cells (Figure 1A & 1C). The kinetics of DHA uptake was typical of other cell lines. Kinetic analysis supported a two phase uptake model of DHA with the initial rate of uptake thought to correspond to transport through the glucose transporters, and the slower second rate thought to correspond to the intracellular conversion of DHA to AA (Figure 1B & 1D) (11).

Figure 1. DHA, but not AA is taken up in malignant hematopoietic cells.

K562 cells (A, B) and RL cells (C, D) were exposed to either AA or DHA. Dose-dependent uptake after 1 hour of exposure to varying concentrations of either AA or DHA (0–750 μM) (A, C). Time-dependent uptake after exposure to either AA or DHA (500 μM) for 0–240 seconds (B, D). Three separate experiments were conducted in triplicate and the results shown represent the mean values and the standard deviations of a single representative experiment.

Vitamin C protects RL and K562 cells from the cytotoxic effects of antineoplastic agents

To test whether vitamin C exposure could protect cells from chemotherapeutic agents in which the generation of ROS is considered to contribute to cytotoxicity, we used chemotherapeutic agents that act through various mechanisms: vincristine (VCR) is a vinca alkaloid that binds tubulin and inhibits cell division; doxorubicin (DOX) is an anthracycline that intercalates into DNA and also inhibits topoisomerase II; methotrexate (MTX) inhibits dihydrofolate reductase, leading to inhibition of DNA synthesis; cisplatin (CDDP) forms DNA crosslink adducts; imatinib (IMAT) mesylate is a selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor that inhibits bcr-abl, the constitutively activated tryosine kinase that plays a central pathophysiologic role in CML(25, 26). Although ROS have been reported to play a role in mediating the therapeutic cytotoxic effects of cisplatin and doxorubicin (4, 5), they are not considered to play an important mechanistic role in the efficacy of the other agents tested.

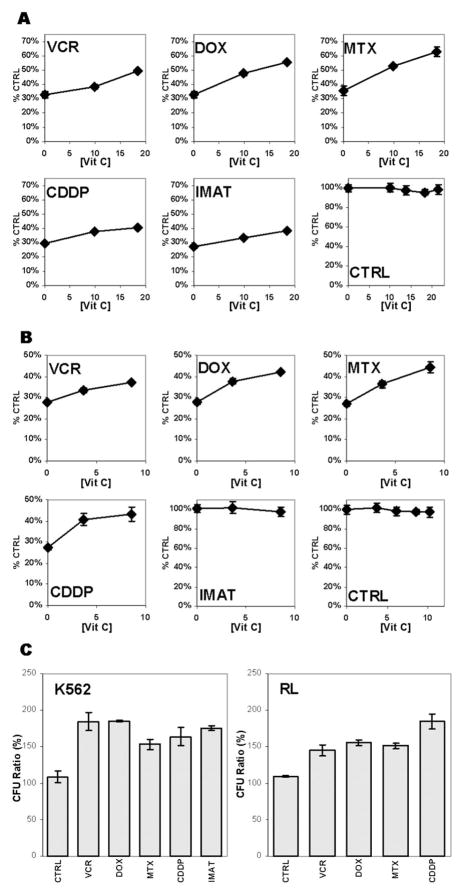

When cells were exposed to DHA to increase intracellular AA levels, washed and subsequently treated with antineoplastic agents at concentrations corresponding to an IC75, we found that the cytotoxicity of all agents tested, regardless of mechanism of action, was reduced (Figure 2A). The absolute magnitude of the reductions ranged from 11% (VCR) to 27% (MTX) and corresponded to relative reduction in cytotoxicity ot 30–70%. Cytotoxicity was reduced more in cells that had higher intracellular concentrations of vitamin C, indicating a dose-dependent effect. High intracellular concentrations of vitamin C, however, had no effect on either the viability or proliferation of untreated cells. RL cells pretreated with vitamin C demonstrated a similar reduction in chemotherapy-mediated cytotoxicity; with the exception that imatinib was not cytotoxic (Figure 2B). The lack of imatinib cytotoxicity was expected because RL cells are not transformed by the bcr-abl kinase. These findings were broadened to show that increased intracellular vitamin C also antagonizes the effects of chemotherapeutic agents as measured by the ability of drug-treated cells to form colonies in methylcellulose (Figure 2C). This indicates that the protection conferred by vitamin C treatment extends to cells with in vitro clonogenic potential. These results also show that vitamin C can attenuate the cytotoxicity of antineoplastic drugs in cells of both myeloid and lymphoid lineage and reduces the effectiveness of agents that act through a broad range of mechanisms.

Figure 2. Vitamin C attenuates the cytotoxicity of antineoplastic agents in K562 and RL cells without inhibiting normal cell growth.

K562 (A) and RL (B) cells were loaded with DHA to varying concentrations of intracellular vitamin C. The cells were washed and treated with either vehicle or antineoplastic agents for 48 hours. Cell viability was measured by Trypan Blue exclusion. The results are plotted as the percentage of viable cells compared to cells not treated with either vitamin C or antineoplastic agents. The effect of vitamin C on colony formation after treatment with antineoplastic agents was determined (C). K562 cells, either treated with vehicle or with vitamin C to an internal concentration of 18 mM vitamin C, and RL cells either treated with vehicle or with vitamin C to an internal concentration of 8.5 mM vitamin C were washed and then treated with either vehicle (−) or antineoplastic agents for 48 hours. The cells were plated in methylcellulose and colony numbers were compared to, and expressed pair-wise, as a percentage of CFU’s resulting from treatment with antineoplastic agents without vitamin C pretreatment. Three separate experiments were conducted in triplicate and the results shown represent the mean values and the standard deviations of a single representative experiment.

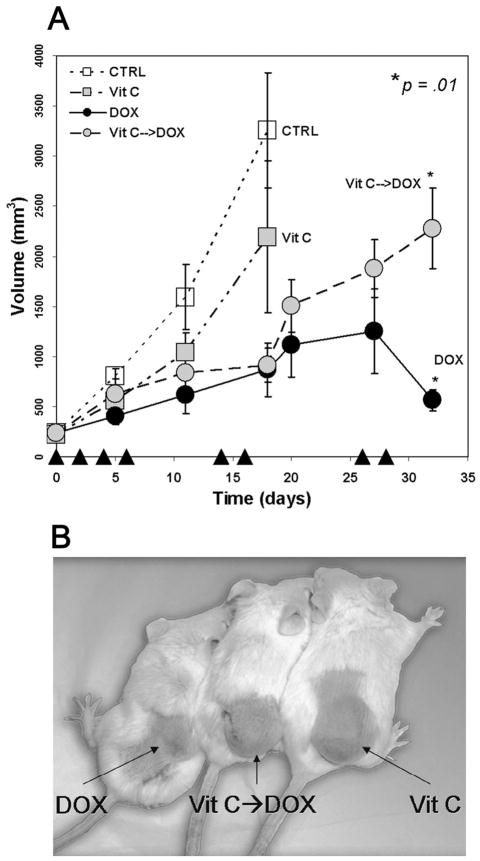

Vitamin C antagonizes doxorubicin cytotoxicity in murine RL xenografts

We used RL cells to generate xenograft tumors in ICR SCID mice to determine whether vitamin C attenuates the effects of chemotherapy in vivo. As expected, doxorubicin treatment reduced tumor growth compared to untreated mice (Figure 3A). While treatment with DHA alone did not appreciably alter tumor growth compared with untreated mice (p=0.114), mice treated with DHA 2 hours prior to doxorubicin administration had tumors that were approximately four times larger than tumors in mice treated with doxorubicin alone at day 32 (p=0.01) (Figure 3A, 3B). At day 32, because mice treated with DHA prior to doxorubicin administration had average tumor volumes greater than 2000 mm3, the animals were sacrificed to assess intratumor doxorubicin and AA levels coincident with animals treated only with doxorubicin. The intratumor concentration of vitamin C, in DHA-treated animals was 5.5±0.9 mM compared with 0.65±0.08 mM in vehicle-treated mice, indicating that DHA treatment effectively increased the intratumor concentration of vitamin C. The doxorubicin concentration in the tumors of vitamin C-treated mice was 9.8±1.1 μgdox/mgtumor. In the tumors of mice that did not receive vitamin C, the doxorubicin concentration was 9.9±2.0 μgdox/mgtumor. This demonstrates that DHA treatment did not alter tumor cell uptake of doxorubicin. Therefore, vitamin C administered prior to doxorubicin substantially reduced the effectiveness of treatment and suggests, in a preclinical model, that vitamin C might interfere with cancer chemotherapy inside the cell rather than affecting drug clearance or tumor uptake.

Figure 3. Vitamin C attenuates the cytotoxicity of antineoplastic agents in vivo.

ICR SCID mice were xenografted with RL cells in the right flank. Cohorts of 5 mice were treated with vehicle control, 1 mg/kg DOX, 250mg/kg DHA or DHA 2 hours prior to DOX on days as noted (▲), and tumor volumes were measured (A). Statistics were single factor ANOVA. Representative animals on day 28 from the left are DOX, DHA prior to DOX, and DHA. The background color was slightly modified to enhance contrast and the image was converted from color to black and white. (B). Two separate experiments were conducted in quintuplicate and the results shown represent the mean values and the standard deviations of a single representative experiment.

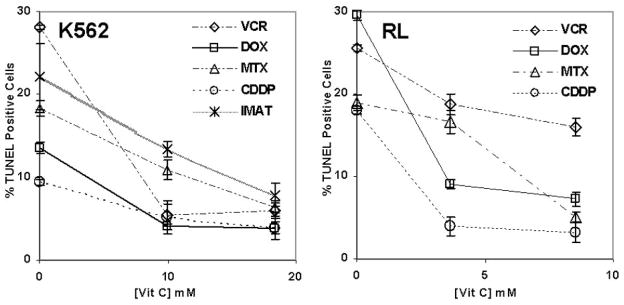

Vitamin C decreases apoptosis, but does not affect Pgp expression

We next investigated the mechanism by which vitamin C attenuates the cytotoxic effects of antineoplastic agents. Pretreatment of cells with vitamin C led to a dose-dependent decrease in apoptosis with all agents tested. At the highest concentrations of intracellular vitamin C, apoptosis was reduced between 37–82% as measured by TUNEL (Figure 4). The possibility that vitamin C treatment alters the effectiveness of chemotherapeutic agents by up-regulating the p-glycoprotein (Pgp) efflux pump, was excluded by the finding that Pgp expression on the cell surface was unaltered by vitamin C treatment (Supplemental Figure 1A). This result is consistent with our finding that intratumor doxorubicin concentrations are similar between untreated mice and mice treated with vitamin C.

Figure 4. Vitamin C reduces the percentage of apoptotic cells.

K562 and RL cells were treated with DHA to achieve varying concentrations of intracellular vitamin C. The cells were washed and treated with antineoplastic agents for up to 48 hours. Apoptosis was measured by TUNEL after 48 hours of treatment. Results are expressed as a percentage of TUNEL positive cells. Three separate experiments were conducted in triplicate and the results shown represent the mean values and the standard deviations of a single representative experiment.

Vitamin C elimination kinetics is not affected by treatment with antineoplastic agents

To determine whether antineoplastic agents altered the kinetics of vitamin C elimination, K562 and RL were loaded with L-[14C]ascorbic acid, by treatment with L[14C]dehydroascorbic acid. The intracellular concentration of [14C] in cell pellets was measured over 24 hr (Supplemental Figure 1B). There was no significant difference in [14C] elimination with any of the agents tested and untreated control cells. These findings are consistent with the observation that there was no difference in vitamin C concentration within the xenogenic tumors of mice treated with doxorubicin. These results suggest that the protective effect of vitamin C is not a result of improved antioxidant retention.

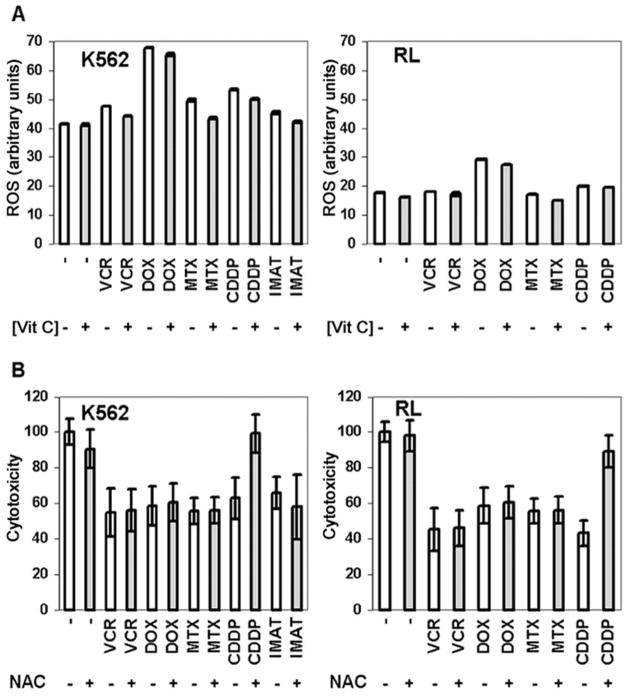

Vitamin C treatment results in small reductions in ROS

When K562 and RL cells were treated with antineoplastic agents, we found that doxorubicin and, to a lesser extent, cisplatin, increased the intracellular levels of ROS, as has been previously reported (4, 5), while other agents had little discernible effect on ROS levels (Figure 5A). In cells treated with chemotherapeutic drugs, as well as in untreated cells, pretreatment of cells with DHA caused a small reduction in intracellular levels of ROS. Although the reduction in intracellular ROS levels was statistically significant (p≤0.02), the magnitude of the reduction in ROS appeared to be minor in comparison to the reduction in cytotoxicity. To further investigate the role of ROS in attenuating cytotoxicity, we treated K562 and RL cells with N-acetylcysteine. N-acetylcysteine and vitamin C both help to replenish important ROS-quenching thiols such as glutathione that play an important role in neutralizing ROS and are both considered important antioxidants (27). When cells were treated with N-acetylcysteine before and during exposure to chemotherapeutic agents, only cytotoxicity mediated by cisplatin was reduced (Figure 5B). Although the ability of thiols to protect cells from cisplatin has been described previously (28), these results demonstrate that vitamin C has a more general cytoprotective profile, suggesting a different mechanism of action that could be unrelated to the antioxidant effects of vitamin C.

Figure 5. Vitamin C has minimal effects on intracellular ROS and has a different effect on cytotoxicity than N-acetyl cysteine.

K562 and RL cells were either untreated (−) or treated (+) to internal vitamin C (AA) concentrations of 18 mM and 8.5 mM respectively, and treated with antineoplastic agents for 6 hours. ROS was measured by incubation with 0.1μg/mL CM-H2DCFDA (A). Results are expressed as median fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units). K562 and RL cells were treated with antineoplastic agents for 48 hours in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 25 mM N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (B). Cell viability was measured by Trypan Blue exclusion and results are expressed as a percent of cells not concomitantly treated with NAC. Three separate experiments were conducted in triplicate and the results shown represent the mean values and the standard deviations of a representative experiment.

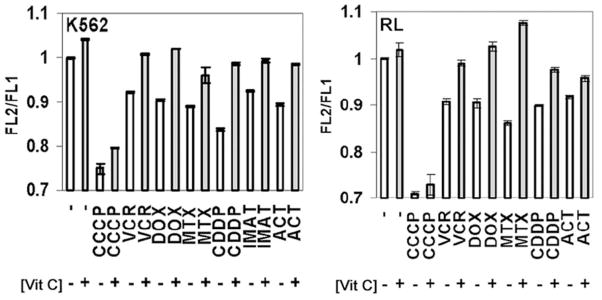

Vitamin C treatment helps to preserve mitochondrial membrane potential

Vitamin C is taken up by the mitochondria and is able to preserve mitochondrial membrane potential after exposure to apoptotic stimuli such as fas ligand and gamma irradiation (18, 29, 30). We assessed mitochondrial membrane potential in RL and K562 cells treated with antineoplastic agents and found that all agents tested led to a rapid reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential (Figure 6). Pretreatment with DHA prevented early chemotherapy-induced mitochondrial membrane depolarization with all agents tested. Mitochondrial membrane potentials in either RL or K562 cells 6 hours after treatment with chemotherapeutic drugs were similar to untreated control cells after treatment with vitamin C. These results were consistent with the notion that vitamin C exerts its inhibitory effects against antineoplastic drugs by protecting cells from mitochondrial membrane depolarization. To evaluate this possibility, we studied the effects of vitamin C on actinonin (ACT), an antibiotic that targets peptide deformylase (31), an enzyme that processes proteins encoded by mitochondrial DNA in eukaryotic cells. Actinonin has broad antineoplastic activity in vitro and previous investigation suggested that mitochondrial membrane depolarization plays a central role in mediating differential activity in normal and transformed cells (31). We found that pretreatment with vitamin C inhibits the cytotoxic effects of actinonin in K562 and RL cells (Figure 2). As with other cell lines, actinonin exposure led to mitochondrial membrane depolarization in K562 and RL cells that was inhibited by pretreatment with vitamin C (Figure 6). Although the approximate 15% maximal reduction of Δψ m observed with antineoplastic treatment at 6 hours may appear to be a mild affect, we have recently shown in a lymphoma model that targeting Bcl-2 family members with the BH3-mimetic AT-101 leads to a maximal 10% reduction in Δψ m at 12 hours and that this apparently mild depolarization induced further depolarization and apoptosis at later time points both in vitro and in vivo(32).

Figure 6. Vitamin C antagonizes mitochondrial membrane depolarization mediated by antineoplastic agents.

Cells were stained with 10 μg/mL JC-1, washed, and equilibrated for 1 hour at 37°C. K562 and RL cells either untreated (−) or loaded (+) with 18 mM and 8.5 mM vitamin C (AA), respectively were exposed to antineoplastic agents for 6 hours and mitochondrial membrane potential was measured as the ratio of 530 nm to 585 nm fluorescence. Maximal depolarization was determined by exposure to 100 nM carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP). The results are representative of at least 3 separate experiments. The differences in mitochondrial membrane potential between chemotherapy-treated cells with and without pretreatment with vitamin C were statistically significant (p<0.003 in RL cells, p<0.0005 in K562 cells, (student’s t-Test)). Three separate experiments were conducted in triplicate and the results shown represent the mean values and the standard deviations of a representative experiment.

DISCUSSION

The finding that vitamin C antagonized the cytotoxic effects of such a wide range of antineoplastic agents was unexpected. We had originally hypothesized that vitamin C would antagonize the cytotoxic effects of antineoplastic agents that use ROS to mediate some activity. Our data indicate, however, that pretreatment with DHA attenuates the antineoplastic activity of chemotherapeutic agents, including highly selective agents, that do not lead to ROS generation. While it is possible that small effects on ROS may exert disproportionate effects on cytotoxicity, it seems more likely that other mechanisms are involved. A recent study suggested that both vitamin C and N-acetylcysteine may diminish tumorigenesis through effects on hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1 related pathways rather than by preventing direct oxidative damage to DNA (33). While many antineoplastic agents target DNA, our findings suggest that the spectrum of activity of vitamin C is substantially broader than N-acetylcysteine, which antagonized only cisplatin cytotoxicity. It has been shown that vitamin C antagonizes fas ligand-mediated mitochondrial membrane depolarization (29). Previous studies have also shown that cisplatin, doxorubicin, etoposide and several other agents result in mitochondrial membrane depolarization (34, 35). We have expanded the number of antineoplastic agents that lead to rapid mitochondrial membrane depolarization and have found that this depolarization can be inhibited by vitamin C. A substantial body of work has shown that mitochondrial membrane depolarization plays an important role in regulating cell death (36, 37). Thus, mitochondrial membrane depolarization may be a common mechanism that contributes to the cytotoxicity of many chemotherapeutic agents, including highly selective agents such as imatinib.

While the effects of vitamin C on intracellular targets in the nucleus or the cytoplasm, for example, cannot be excluded, we hypothesize that the mitochondria are an important site of action for vitamin C. Vitamin C enters the mitochondria and recent work shows that transport into the mitochondria occurs through the glucose transporters (18, 38, 39). Although treatment with antineoplastic agents does not generally lead to increased intracellular ROS, it is possible that vitamin C in the mitochondria plays a role in quenching local ROS. Alternatively, vitamin C in the mitochondria may help to stabilize respiratory electron transport, thereby preserving the most efficient means of energy generation and maintaining overall cellular fitness. The role of vitamin C in protecting mitochondria from cytotoxic agents is supported by the finding that vitamin C antagonizes the cytotoxic effects of actinonin. Actinonin specifically inhibits human mitochondrial peptide deformylase, an enzyme whose central function appears to be the deformylation of the thirteen proteins encoded by mitochondria, all of which play vital roles in electron transport and subsequent energy generation (31). Although the precise mechanism and kinetics through which vitamin C mediates its protective effects remain unknown, the finding that vitamin C protects cells from actinonin toxicity suggests that the ability of vitamin C to stabilize the mitochondria plays a central role in exerting its cytoprotective profile.

Taken together, our data demonstrate that pharmacologic concentrations of intracellular vitamin C antagonize the therapeutic cytotoxic effects of antineoplastic chemotherapeutic agents. This finding could have important clinical relevance given the wide use of vitamin C as a nutritional supplement. These results suggest that supplemental vitamin C may have adverse consequences in patients who are receiving cancer chemotherapy. Such a supposition, however, would need confirmation in other therapeutic models or in human trials. While we have used DHA in our experimental model to achieve high intracellular concentrations of vitamin C, there is evidence from murine models of human prostate cancer xenografts that ascorbic acid may be converted to DHA in the peri-tumor milieu, leading to higher intracellular concentrations of vitamin C (40). Although we studied cells derived from hematopoietic malignancies, intracellular vitamin C accumulation has been observed in cell lines derived from solid tumors as well as solid tumor xenografts(40), suggesting that our observations are unlikely to be unique to hematologic cancers. This is supported by clinical evidence showing that intratumor concentrations of vitamin C are higher in cancer cells than in adjacent normal tissue in patients who did not take supplemental vitamin C (41). It was notable that the concentration of vitamin C measured in the tumors of the mice in this study was similar to the concentration of vitamin C that can be achieved in human leukocytes with oral vitamin C supplementation (42, 43), suggesting that our study conditions were relevant to clinical conditions. Therefore, it is possible that vitamin C supplementation may alter the effectiveness of commonly used chemotherapy agents and adversely influence treatment outcome.

Supplementary Material

K562 and RL were treated with 500μM DHA (solid gray) to internal concentrations of 18 mM and 8.5 mM vitamin C, respectively, or vehicle alone (black line) and were then incubated for 48 hours under normal growth conditions. P-glycoprotein expression was determined with U1C2-A488 Pgp antibody by flow cytometry (A). Two separate experiments were conducted in triplicate and the results shown are the histograms of a representative experiment. Vitamin C retention after antineoplastic administration for 24 hours was measured by scintillation spectrometry normalized to percent of initial concentration (B). Two separate experiments were conducted in triplicate and the results shown represent the mean values and the standard deviations of a representative experiment.

Acknowledgments

Supported by New York State Department of Health (M.L.H., D.W.G), the National Institutes of Health (CA30388, (D.W.G.), CA55349, (D.A.S.)), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar in Research Award (O.A.O.), Doris Duke Distinguished Clinical Scientist Award (D.A.S.) and the Lewis Family Foundation (M.L.H.)

This work is dedicated to the memory of our friend and colleague, David W. Golde, M.D. We are grateful to Dr. William Bornmann for supplying the imatinib mesylate and Dr. Anna Kenney for critical review of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cameron E, Pauling L, Leibovitz B. Ascorbic acid and cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1979;39:663–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golde DW. Vitamin C in cancer. Integr Cancer Ther. 2003;2:158–9. doi: 10.1177/1534735403002002009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron E, Pauling L. Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: reevaluation of prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:4538–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.9.4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lutzky J, Astor MB, Taub RN, et al. Role of glutathione and dependent enzymes in anthracycline-resistant HL60/AR cells. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4120–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cossarizza A, Franceschi C, Monti D, et al. Protective effect of N-acetylcysteine in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced apoptosis in U937 cells: the role of mitochondria. Exp Cell Res. 1995;220:232–40. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dai J, Weinberg RS, Waxman S, Jing Y. Malignant cells can be sensitized to undergo growth inhibition and apoptosis by arsenic trioxide through modulation of the glutathione redox system. Blood. 1999;93:268–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grad JM, Cepero E, Boise LH. Mitochondria as targets for established and novel anti-cancer agents. Drug Resist Updat. 2001;4:85–91. doi: 10.1054/drup.2001.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karasavvas N, Carcamo JM, Stratis G, Golde DW. Vitamin C protects HL60 and U266 cells from arsenic toxicity. Blood. 2005;105:4004–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsukaguchi H, Tokui T, Mackenzie B, et al. A family of mammalian Na+-dependent L-ascorbic acid transporters. Nature. 1999;399:70–5. doi: 10.1038/19986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vera JC, Rivas CI, Fischbarg J, Golde DW. Mammalian facilitative hexose transporters mediate the transport of dehydroascorbic acid. Nature. 1993;364:79–82. doi: 10.1038/364079a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vera JC, Rivas CI, Zhang RH, Farber CM, Golde DW. Human HL-60 myeloid leukemia cells transport dehydroascorbic acid via the glucose transporters and accumulate reduced ascorbic acid. Blood. 1994;84:1628–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guaiquil VH, Farber CM, Golde DW, Vera JC. Efficient transport and accumulation of vitamin C in HL-60 cells depleted of glutathione. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9915–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guaiquil VH, Vera JC, Golde DW. Mechanism of vitamin C inhibition of cell death induced by oxidative stress in glutathione-depleted HL-60 cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40955–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galleano M, Aimo L, Puntarulo S. Ascorbyl radical/ascorbate ratio in plasma from iron overloaded rats as oxidative stress indicator. Toxicol Lett. 2002;133:193–201. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(02)00196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterkofsky B. Ascorbate requirement for hydroxylation and secretion of procollagen: relationship to inhibition of collagen synthesis in scurvy. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:1135S–40S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.6.1135s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levine M, Dhariwal KR, Washko P, et al. Ascorbic acid and reaction kinetics in situ: a new approach to vitamin requirements. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1992;(Spec No):169–72. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.38.special_169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rebouche CJ. Ascorbic acid and carnitine biosynthesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:1147S–52S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.6.1147s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, Cobb CE, Hill KE, Burk RF, May JM. Mitochondrial uptake and recycling of ascorbic acid. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;387:143–53. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X, Cobb CE, May JM. Mitochondrial recycling of ascorbic acid from dehydroascorbic acid: dependence on the electron transport chain. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;403:103–10. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00205-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lutsenko EA, Carcamo JM, Golde DW. Vitamin C prevents DNA mutation induced by oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16895–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201151200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.May JM, Mendiratta S, Qu ZC, Loggins E. Vitamin C recycling and function in human monocytic U-937 cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:1513–23. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vera JC, Rivas CI, Velasquez FV, Zhang RH, Concha, Golde DW. Resolution of the facilitated transport of dehydroascorbic acid from its intracellular accumulation as ascorbic acid. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23706–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agus DB, Gambhir SS, Pardridge WM, et al. Vitamin C crosses the blood-brain barrier in the oxidized form through the glucose transporters. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2842–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI119832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang J, Agus DB, Winfree CJ, et al. Dehydroascorbic acid, a blood-brain barrier transportable form of vitamin C, mediates potent cerebroprotection in experimental stroke. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11720–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171325998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertino JR, O’Connor OA. Oncologic Disorders. In: Carruthers SG, Hoffman BB, Melmon KL, Nierenberg DW, editors. Clinical Pharmacology. 4. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000. pp. 799–871. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Druker BJ, Tamura S, Buchdunger E, et al. Effects of a selective inhibitor of the Abl tyrosine kinase on the growth of Bcr-Abl positive cells. Nat Med. 1996;2:561–6. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meister A. Glutathione-ascorbic acid antioxidant system in animals. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:9397–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuhas JM, Spellman JM, Culo F. The role of WR-2721 in radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. Cancer Clin Trials. 1980;3:211–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez-Cruz I, Carcamo JM, Golde DW. Vitamin C inhibits FAS-induced apoptosis in monocytes and U937 cells. Blood. 2003;102:336–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Witenberg B, Kletter Y, Kalir HH, et al. Ascorbic acid inhibits apoptosis induced by X irradiation in HL60 myeloid leukemia cells. Radiat Res. 1999;152:468–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee MD, She Y, Soskis MJ, et al. Human mitochondrial peptide deformylase, a new anticancer target of actinonin-based antibiotics. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1107–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI22269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paoluzzi L, Gonen M, Gardner JR, et al. Targeting Bcl-2 family members with the BH3 mimetic AT-101 markedly enhances the therapeutic effects of chemotherapeutic agents in in vitro and in vivo models of B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008 doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-129833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao P, Zhang H, Dinavahi R, et al. HIF-Dependent Antitumorigenic Effect of Antioxidants In Vivo. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:230–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Decaudin D, Geley S, Hirsch T, et al. Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL antagonize the mitochondrial dysfunction preceding nuclear apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Res. 1997;57:62–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Costantini P, Jacotot E, Decaudin D, Kroemer G. Mitochondrion as a novel target of anticancer chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1042–53. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.13.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marchetti P, Castedo M, Susin SA, et al. Mitochondrial permeability transition is a central coordinating event of apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1155–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green DR, Kroemer G. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science. 2004;305:626–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1099320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sagun KC, Carcamo JM, Golde DW. Vitamin C enters mitochondria via facilitative glucose transporter 1 (Glut1) and confers mitochondrial protection against oxidative injury. Faseb J. 2005;19:1657–67. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4107com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujimoto Y, Matsui M, Fujita T. The accumulation of ascorbic acid and iron in rat liver mitochondria after lipid peroxidation. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1982;32:397–9. doi: 10.1254/jjp.32.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agus DB, Vera JC, Golde DW. Stromal cell oxidation: a mechanism by which tumors obtain vitamin C. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4555–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Langemann H, Torhorst J, Kabiersch A, Krenger W, Honegger CG. Quantitative determination of water- and lipid-soluble antioxidants in neoplastic and non-neoplastic human breast tissue. Int J Cancer. 1989;43:1169–73. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bergsten P, Amitai G, Kehrl J, Dhariwal KR, Klein HG, Levine M. Millimolar concentrations of ascorbic acid in purified human mononuclear leukocytes. Depletion and reaccumulation. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2584–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levine M, Conry-Cantilena C, Wang Y, et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3704–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

K562 and RL were treated with 500μM DHA (solid gray) to internal concentrations of 18 mM and 8.5 mM vitamin C, respectively, or vehicle alone (black line) and were then incubated for 48 hours under normal growth conditions. P-glycoprotein expression was determined with U1C2-A488 Pgp antibody by flow cytometry (A). Two separate experiments were conducted in triplicate and the results shown are the histograms of a representative experiment. Vitamin C retention after antineoplastic administration for 24 hours was measured by scintillation spectrometry normalized to percent of initial concentration (B). Two separate experiments were conducted in triplicate and the results shown represent the mean values and the standard deviations of a representative experiment.