Abstract

Female mosquitoes of some species are generalists and will blood-feed on a variety of vertebrate hosts, whereas others display marked host preference. Anopheles gambiae and Aedes aegypti have evolved a strong preference for humans, making them dangerously efficient vectors of malaria and Dengue haemorrhagic fever1. Specific host odours likely drive this strong preference since other attractive cues, including body heat and exhaled carbon dioxide (CO2) are common to all warm-blooded hosts2, 3. Insects sense odours via several chemosensory receptor families, including the odorant receptors (ORs). ORs are membrane proteins that form heteromeric odour-gated ion channels4, 5 comprised of a variable ligand-selective subunit and an obligate co-receptor called Orco6. Here we use zinc-finger nucleases to generate targeted mutations in the Ae. aegypti orco gene to examine the contribution of Orco and the OR pathway to mosquito host selection and sensitivity to the insect repellent DEET. orco mutant olfactory sensory neurons have greatly reduced spontaneous activity and lack odour-evoked responses. Behaviourally, orco mutant mosquitoes have severely reduced attraction to honey, an odour cue related to floral nectar, and do not respond to human scent in the absence of CO2. However, in the presence of CO2, female orco mutant mosquitoes retain strong attraction to both human and animal hosts, but no longer strongly prefer humans. orco mutant females are attracted to human hosts even in the presence of DEET, but are repelled upon contact, indicating that olfactory- and contact-mediated effects of DEET are mechanistically distinct. We conclude that the OR pathway is crucial for an anthropophilic vector mosquito to discriminate human from non-human hosts and to be effectively repelled by volatile DEET.

In the vinegar fly, Drosophila melanogaster, Orco is an obligate olfactory co-receptor7 that forms a complex with all ligand-selective ORs and is required for efficient trafficking to olfactory sensory neuron dendrites8. We reasoned that mutations in Ae. aegypti orco should eliminate signalling mediated by all 131 ligand-selective ORs in this mosquito9. To obtain heritable targeted null mutations in the Aedes aegypti orco gene, we used zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs), which are fusion proteins of a sequence-specific DNA binding protein and a nuclease that induces mutagenic double-stranded breaks10, 11.

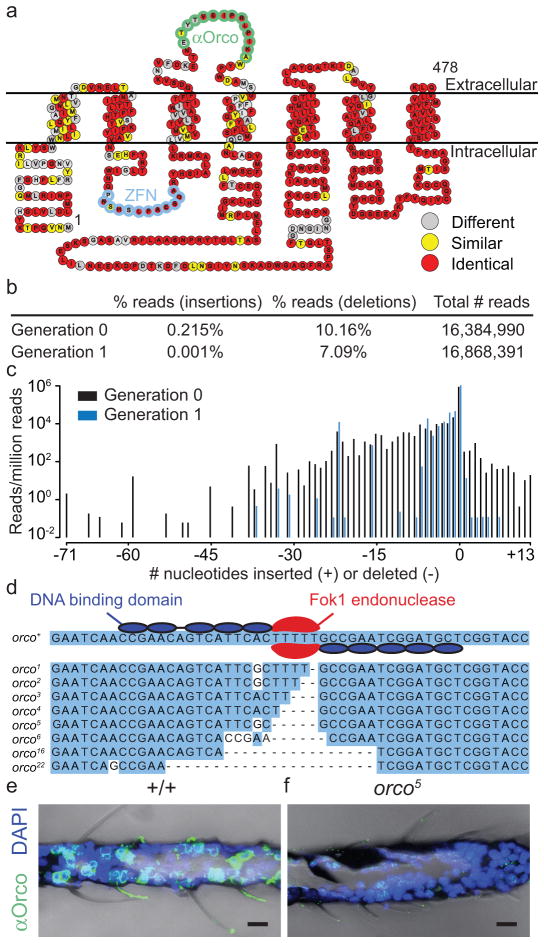

We first used ZFNs12 to disrupt Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) in a transgenic strain of Ae. aegypti and detected a wide range of insertion and deletion events in GFP (Supplementary Fig. 1). We next injected ZFNs designed to target the orco locus (Fig. 1a) into wild-type mosquito embryos. The orco ZFNs induced mutations at high efficiency in adults derived from injected embryos (G0) as well as their progeny (G1) (Fig. 1b–d). Three mutant alleles were characterized, orco2, orco5, and orco16, and are predicted to produce truncated Orco protein. We did not detect Orco expression in antennae in any of these homozygous orco mutant alleles (Fig. 1e–f and data not shown). Using these homozygous mutants, we further generated heteroallelic orco mutant combinations to control for independent background mutations.

Figure 1. Targeted mutagenesis of Ae. aegypti orco.

a, Snake plot of Ae. aegypti Orco with amino acids colour-coded to indicate conservation with Drosophila melanogaster. The amino acids encoded by the DNA bound by the orco ZFN (blue) and the epitope of the Drosophila anti-Orco antibody (green) are indicated. b, Analysis of orco ZFN mutagenesis in Ae. aegypti G0 and G1 animals assayed by Illumina sequencing of an amplicon containing the ZFN cut site. c, Frequency of insertions/deletions expressed as the number of sequence reads per million reads. d, Top: schematic of orco ZFN pair binding to orco DNA. Bottom: orco mutant alleles. e–f, Immunofluorescence of frozen sections of wild-type (e) and orco5 mutant (f) antennae (α-Drosophila Orco, green; DAPI nuclear stain, blue). Scale bar: 10 μm.

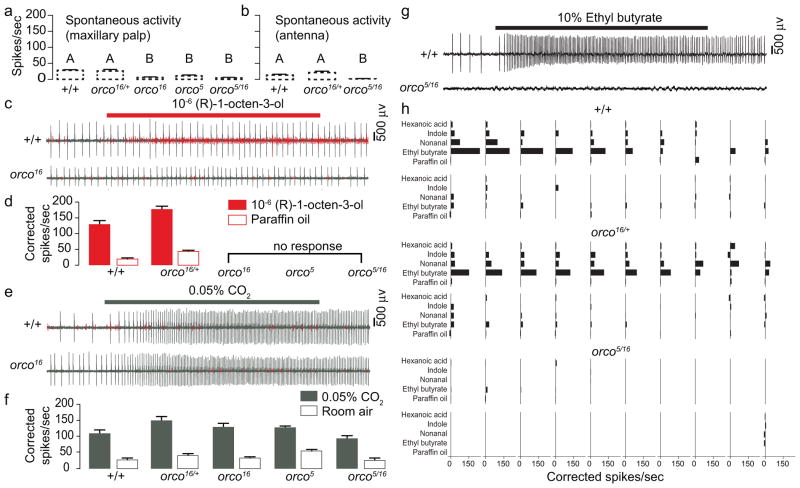

orco mutants exhibited severely impaired electrophysiological responses (Fig. 2). Spontaneous activity in maxillary palp (Fig. 2a) and antennal (Fig. 2b) sensilla was reduced relative to wild-type and heterozygous controls, as observed previously in Drosophila orco mutants7. We were unable to locate any maxillary palp capitate-peg sensilla responsive to a ligand for OR8/Orco, (R)-1-octen-3-ol13–15, in orco5, orco16, or orco5/16 mutant mosquitoes (0/25, 0/21, 0/15, respectively), but readily detected them in wild-type and heterozygous orco16/+ animals (19/29 and 5/7 sensilla tested, respectively) (Fig. 2c–d). Insect chemosensory responses to CO2 are orco-independent16 and capitate-peg sensilla in all genotypes responded normally to CO2 (Fig. 2e–f). Likewise, we were unable to locate any antennal short blunt-tipped (sbt) trichoid sensilla responding to a panel of odorants selected from those previously shown to activate neurons in subsets of antennal sbt sensilla17, 18 (Fig. 2g–h). As expected, a subset of sbt sensilla from wild-type (13/20) and heterozygous (13/20) control mosquitoes responded to one or more odorants in the panel (Fig. 2g–h). Our results show that in orco mutants, both antennal and maxillary palp neurons fail to respond to the odours tested, suggesting that as in Drosophila, orco is required for the function of ligand-selective ORs.

Figure 2. Reduced spontaneous activity and loss of odour-evoked responses in orco mutant olfactory neurons.

a–b, Spontaneous activity in the small-amplitude cell in capitate-peg sensilla on the maxillary palp (a) or in the large-amplitude cell in sbt sensilla on the antenna (b) recorded from the indicated genotypes. Data are plotted as mean±S.E.M. [maxillary palp n=19 (+/+), n=5 (orco16/+), n=21 (orco16), n=25 (orco5), n=15 (orco5/16); antenna n=20 (+/+), n=20 (orco16/+), n=20 (orco5/16)]. Values that are significantly different are labelled with different letters (1-way ANOVA for both comparisons, p<0.0001 followed by Tukey’s HSD test). c, Representative spike traces of maxillary palp neurons stimulated with (R)-1-octen-3-ol (10−6 dilution in paraffin oil). Small-amplitude spikes are in red. d, Summary of small-amplitude spikes evoked by (R)-1-octen-3-ol (solid bars) or paraffin oil solvent (open bars). Data are presented as mean±S.E.M. e, Representative spike traces of maxillary palp neurons stimulated with CO2 (0.05%). Large amplitude spikes are in grey. f, Summary of large-amplitude spikes evoked by CO2 (solid bars) or air (open bars). Data are plotted as mean±S.E.M. [n=7 (+/+), n=6 (orco16/+), n=9 (orco16), n=8 (orco5), n=6 (orco5/16)]. There was no difference in CO2-evoked spikes between genotypes except for those between orco16/+ and orco5/16 (1-way ANOVA, p=0.0232). g, Representative spike traces of sbt antennal neurons of the indicated genotypes stimulated for 1 sec with 10% ethyl butyrate. h, odour-evoked responses of 20 sbt sensilla for each of the indicated genotypes.

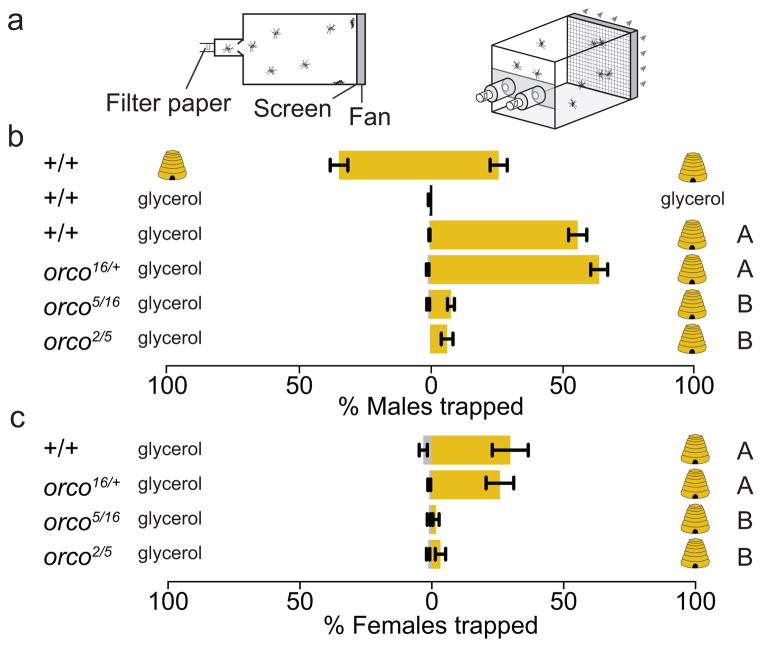

We investigated whether these electrophysiological defects translate into altered responses to important olfactory cues using a modified two-port Gouck olfactometer19 (Fig. 3a). Both male and female mosquitoes feed on nectar to satisfy their metabolic needs and are attracted to floral and honey odors20. We quantified attraction of fasted male and female mosquitoes to honey or glycerol, which is odourless and has a viscosity and water content similar to honey. While wild-type and heterozygous control mosquitoes responded to honey, heteroallelic orco mutant mosquitoes showed little to no response (Fig. 3b–c). When fasted, we found no reduction in survival or locomotor activity in orco mutants relative to controls (Supplementary Fig. 2). Thus, these weak responses cannot be explained by a locomotion defect in the mutants.

Figure 3. Disruption of honey odour detection in orco mutants.

a, Diagram of two-port olfactometer used for honey response assay. b–c, Response of male (b) or female (c) mosquitoes to honey (beehive) or glycerol by the indicated genotypes. Wild-type males distributed evenly between the two ports when both contained honey (Student’s t-test, p=0.13; N=8), and did not respond to glycerol (N=7). Genotypes varied significantly in their response to honey (1-way ANOVA, p<0.001; N (males)=10–11; N (females)=7–11).

Genotypes marked with different letters are significantly different by post hoc Tukey’s HSD test.

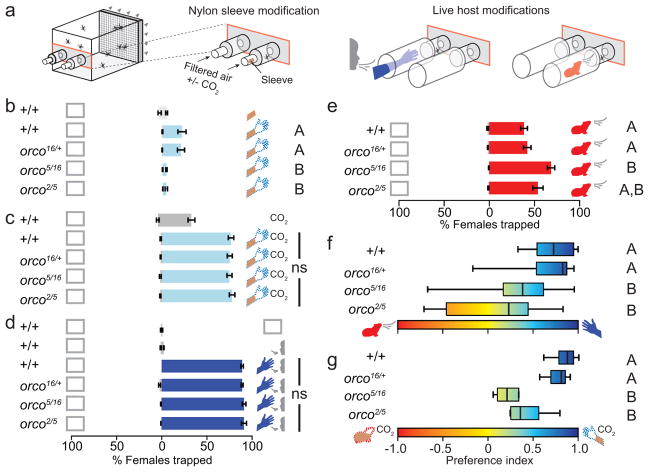

Female mosquitoes additionally feed on vertebrate hosts to acquire nutrients necessary for egg development, and are attracted to host odour. We examined responses of female mosquitoes to human odour trapped on nylon sleeves using the same two-port olfactometer, modified to include carbon-filtered air flow (Fig. 4a). In this assay, wild-type female mosquitoes did not respond to unworn sleeves, but showed moderate attraction to human-scented sleeves (Fig. 4b). In contrast, orco mutant females showed little or no response to host odour (Fig. 4b). Because live hosts emit both odour and CO2, we repeated these experiments in the presence of CO2 (Fig. 4c). Wild-type female mosquitoes showed moderate attraction to CO2 alone, and this response was greatly enhanced when human-scented sleeves were presented along with CO2 (Fig. 4c). Contrary to the defect seen in the absence of CO2, orco mutant females exhibited the same robust response to human odour in the presence of CO2 as controls (Fig. 4c). Likewise, orco mutant females responded at the same robust levels as controls to air that had passed over a live human arm, supplemented with human breath, and tested in a modified version of the same olfactometer (Fig 4a, d).

Figure 4. Disruption of host detection and discrimination in orco mutants.

a, Diagram of modifications to the two-port olfactometer for host assays with female mosquitoes. b, Response to no stimulus (open box), unworn nylon sleeve (sleeve cartoon), or human scented nylon sleeve (dotted hand cartoon) without CO2. Genotypes varied significantly (1-way ANOVA, p<0.0001; N=15). c, Response to CO2 or human scented nylon sleeve with CO2. Genotypes did not differ in their response to human scented nylon sleeves with CO2 (1-way ANOVA, p=0.8881; N=15). d, Response to no stimulus, human breath (face cartoon), or live human (blue). Genotypes did not differ (1-way ANOVA, p=0.8; N=7). e, Response to no stimulus or guinea pig (red). Genotypes differed in responses (1-way ANOVA, p=0.0001; N=12–13). f, Preference index for live human or guinea pig. Variation was significant among both genotypes and human subjects tested (two-way ANOVA, p<0.0001 for genotype and p=0.0015 for subject). g, Preference index for human or guinea pig-scented nylon sleeve. Variation among genotypes was significant (1-way ANOVA; p<0.0001; N=5–6). Data in b–e are plotted as mean±S.E.M. and data in f–g are presented as box plots (black line: median; bounds of boxes: 1st/3rd quartiles, bars: range). In b, e, f, g, genotypes marked with different letters are significantly different by post hoc Tukey’s HSD test.

These results indicate that CO2 synergizes with host odour to rescue the defect in orco mutant attraction, suggesting that mosquitoes possess redundant mechanisms for host odour detection that can only be activated in the presence of CO2. Further, this indicates that olfactory signalling mediated through a second family of chemosensory receptors, the ionotropic receptors (IRs), cannot compensate for the loss of OR function in orco mutants in the absence of CO2.

Most populations of Ae. aegypti strongly prefer human over non-human hosts, prompting us to ask whether the OR pathway is required for host discrimination. We assayed host discrimination between human and guinea pig—an animal host to which Ae. aegypti has been shown to respond19. Both wild-type and orco mutants showed moderate levels of baseline attraction to a live guinea pig (Fig. 4e). We were intrigued by the stronger attraction of orco mutants to guinea pig relative to controls, but note that this difference was statistically significant for only orco5/16. We then offered mosquitoes a choice between air that had passed over a live guinea pig or the arm of one of 14 live human subjects (Fig. 4f). orco mutants were significantly less likely than wild-type to choose the human host, resulting in a lower mean preference index (Fig. 4f). To determine if the reduced preference of mutant mosquitoes for humans depended on host-specific odours alone, we repeated the choice assay but replaced live hosts with host odour collected on nylon sleeves, supplemented with equal amounts of CO2 (Fig. 4g). Under these conditions, control mosquitoes strongly preferred human odour, while orco mutants again showed only a weak preference (Fig. 4g). Overall response rates did not differ between genotypes in either assay (Supplementary Fig. 3a–d). We hypothesize that orco mutants are attracted to vertebrate hosts, but are impaired in their ability to discriminate between them.

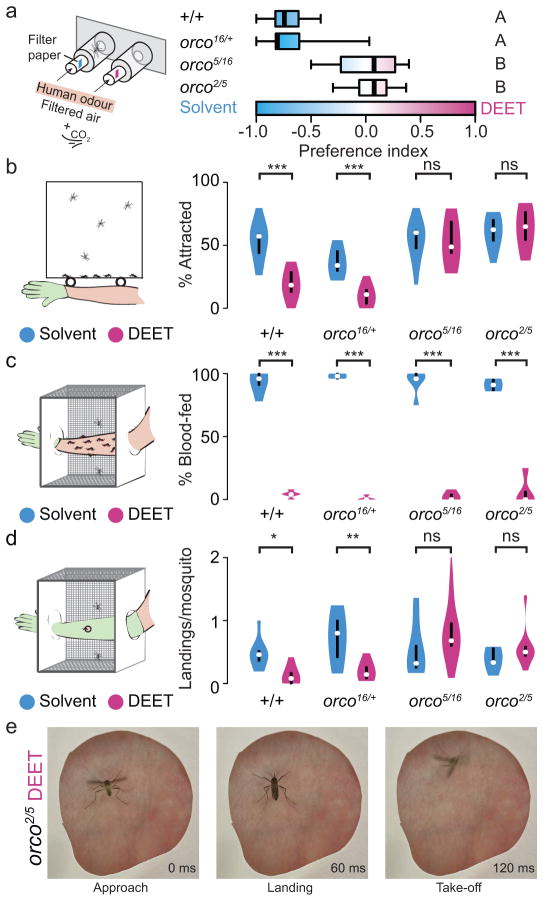

ORs have been proposed to be the major target of the olfactory effect of the insect repellent DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide)21–26. To investigate if DEET can interfere with the strong attraction to human hosts in orco mutants, we tested female orco mutant and control mosquitoes in a two-port olfactometer DEET choice assay (Fig. 5a). Wild-type and heterozygous mosquitoes avoided the port with 10% DEET and accumulated in the solvent port (Fig. 5a). In contrast, orco mutants were insensitive to DEET and accumulated equally in both ports. Genotypes did not differ significantly in their overall response rate (Supplementary Fig. 3e–f).

Figure 5. Female orco mutants are insensitive to volatile DEET but are repelled on contact.

a, Preference for human host-scented traps containing either solvent (cyan) or 10% DEET (magenta). Data are presented as box plots (black line: median; bounds of boxes: 1st/3rd quartiles; bars: range). Genotypes marked with different letters are significantly different by post hoc Tukey’s HSD test (1-way ANOVA; p<0.0001; N=7–16). orco mutant preference is not significantly different from zero (one sample Student’s t-test; orco2/5: p=0.28; orco5/16: p=0.8868). b, Per cent mosquitoes attracted to a human arm treated either with solvent or 10% DEET (Bonferroni corrected t-test comparing solvent and DEET; ***p<0.00025, n.s.: not significant; N=12–14). c, Per cent females blood-fed on a human arm treated with solvent or 10% DEET (Bonferroni-corrected t-test comparing solvent and DEET: ***p<0.00025; N=4–5). d, Per cent landing on human skin treated either with solvent or 10% DEET (Bonferroni corrected t-test comparing solvent and DEET; *p<0.0125, **p<0.0025, n.s.: not significant; N=9). The violin plots in b–d show the median as a white dot and the first and third quartile by the bounds of the black bar. The violins are clipped at the range of the data, except in d, where the orco5/16 DEET violin is further clipped at 2.0, excluding a single outlier 3.76. e, Video stills separated by 60 msec of an orco2/5 mutant mosquito responding to DEET-treated skin.

The DEET choice assay tests mosquito response over a distance of 20—100 cm. To test the olfactory effect of DEET at close range, we used a host proximity assay that measures the effects of DEET over a distance of 2.5—32.5 cm (Fig. 5b). In this assay, a human arm treated with solvent or 10% DEET was placed 2.5 cm from the side of a screened cage. Control mosquitoes were attracted to the arm when it was treated with solvent, but strongly avoided it when treated with DEET. In contrast, orco mutants showed equal attraction to the solvent- and DEET-treated arm (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Movie 1). These results indicate that the olfactory attraction of orco mutants for humans cannot be inhibited by DEET even at close range.

Upon landing on a host, mosquitoes are exposed to taste cues and become susceptible to the contact-mediated repellent effects of DEET. Work in Drosophila suggests that DEET acts on gustatory receptors to induce taste avoidance27. To investigate whether orco mutants are sensitive to the contact-mediated effects of DEET, we carried out an arm-in-cage biting assay in which subjects inserted a solvent- or DEET-treated arm into a mosquito cage (Fig. 5c). DEET treatment inhibited blood feeding of both wild-type and orco mutant females (Fig. 5c). To detect orco mutants contacting DEET-treated skin, we designed a landing assay to image female mosquitoes interacting with exposed skin treated with DEET or solvent (Fig 5d). In contrast to controls, orco mutants approached the host and briefly contacted the DEET-treated skin as often as solvent-treated skin (Fig 5d). A representative orco2/5 mutant mosquito is repelled within 60 msec of contact with DEET-treated skin (Fig 5e). These results support the conclusion that while the olfactory effect of DEET requires an intact OR pathway, the contact repellent activity of DEET is independent of orco function.

In this study, we investigated the requirement for orco and the OR pathway in mosquito appetitive behaviour and sensitivity to the insect repellent DEET. orco mutants are impaired in both honey and host odour attraction. Despite this defect in host odour detection, orco mutants can still respond to live hosts. We propose that the CO2, along with odours that are detected by the IR pathway may constitute more generic vertebrate signals that are sufficient to drive attraction.

The impairment in host preference in orco mutant females suggests a specialization of the OR pathway in Ae. aegypti for host odour discrimination. We hypothesise that the OR/Orco pathway provides information about the specific identity of the host and that specific ORs may mediate preference for humans in this anthropophilic disease vector. A role for ORs in host discrimination is consistent with the broader range of ligands that activates this class of receptors28, 29 compared to IRs30.

Our results also provide definitive proof that orco and the OR pathway are necessary for the olfactory effects of DEET on mosquitoes. A previous study used RNA interference to knock down orco in Anopheles gambiae larvae24 and found that these animals no longer responded to DEET. However, because mosquito larvae are aquatic, these experiments could not distinguish olfactory- and contact-mediated effects. Three mechanisms have been suggested to explain the olfactory repellency of DEET, but no clear consensus has emerged. First, DEET may silence ORs tuned to attractive odours21, 22. Second, DEET may activate one or a few ORs to trigger repulsion23, 24. Third, DEET may act as a “confusant” to modulate the activity of many ORs25, 26. The fact that orco mutants retain very strong olfactory host attraction indicates that the first hypothesis cannot be correct. If the olfactory repellency of DEET acted solely to inhibit the OR pathway, DEET would not be an effective insect repellent. Instead, our results are consistent with the second or third hypotheses. Our genetic analysis of orco mutants indicates that either mechanism must overcome the strong baseline attraction to hosts in the presence of CO2 seen in orco mutants. Finally, we note that the development of an efficient method to generate targeted mutations in Ae. aegypti opens up this important disease vector to comprehensive genetic analysis.

Methods Summary

orco ZFNs were generated using the CompoZr® Custom ZFN Service (Sigma-Aldrich Life Science, St. Louis, MO, USA). Of the 16 ZFN pairs screened, the orco exon 1 ZFN pair used in this study had the greatest activity, comparable to a highly active positive control ZFN pair that targets CCR5. Mutant alleles were detected by Illumina sequencing of an amplicon that contained the ZFN cut site. Mutant alleles were isolated using size-based genotyping of amplicons surrounding the deletion site, allowing us to discriminate heterozygous from homozygous individuals. Mosquitoes were tested for their response to odour cues in a modified version of a Gouck two-port olfactometer19.

Full Methods are in the Supplemental materials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kevin J. Lee and members of the Vosshall lab for comments on the manuscript. Dr. Fyodor Urnov of Sangamo BioSciences suggested the experiments in Supplementary Fig. 1. We thank Dr. Conor McMeniman for initiating the Ae. aegypti GFP ZFN disruption project together with M.D. and for establishing mosquito microinjection at Genetic Services Inc. Scott Dewell of the Rockefeller University Genomics Resource Center provided bioinformatic assistance. Willem Takken and Niels Verhulst suggested the use of nylon stockings in Fig. 4 and 5. Román Corfas provided advice on imaging in Fig. 5b. This work was funded in part by a grant to R. Axel and L.B.V. from the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health through the Grand Challenges in Global Health Initiative. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health to C.S.M. (DC012069) and N.J. and A.A.J. (AI29746). L.B.V. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions: M.D. carried out the experiments in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig 2b–c. E.J.D. carried out the experiments in Supplementary Fig. 2a. N.J. generated the GFP transgenic Ae. aegypti and injected the GFP ZFN for Supplementary Fig. 1 and was supervised by A.A.J. T. N. carried out the experiments in Fig. 2. C.G. reared mosquitoes and genotyped orco mutants. C.S.M. developed the assays used in Fig. 3 and 4 with M.D. and L.S. L.S., M.D., and C.S.M. carried out the experiments in Figs. 3 and 4. L.S., E.J.D., and M.D. developed and carried out the assays in Fig 5. M.D., C.S.M., and L.B.V. wrote the paper.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Besansky NJ, Hill CA, Costantini C. No accounting for taste: host preference in malaria vectors. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:249–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skinner WA, Tong H, Pearson T, Strauss W, Maibach H. Human sweat components attractive to mosquitoes. Nature. 1965;207:661–662. doi: 10.1038/207661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takken W, Knols BG. Odor-mediated behavior of Afrotropical malaria mosquitoes. Annu Rev Entomol. 1999;44:131–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.44.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato K, et al. Insect olfactory receptors are heteromeric ligand-gated ion channels. Nature. 2008;452:1002–1006. doi: 10.1038/nature06850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wicher D, et al. Drosophila odorant receptors are both ligand-gated and cyclic-nucleotide-activated cation channels. Nature. 2008;452:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/nature06861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vosshall LB, Hansson BS. A unified nomenclature system for the insect olfactory co-receptor. Chem Senses. 2011;36:497–498. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjr022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsson MC, et al. Or83b encodes a broadly expressed odorant receptor essential for Drosophila olfaction. Neuron. 2004;43:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benton R, Sachse S, Michnick SW, Vosshall LB. Atypical membrane topology and heteromeric function of Drosophila odorant receptors in vivo. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohbot J, et al. Molecular characterization of the Aedes aegypti odorant receptor gene family. Insect Mol Biol. 2007;16:525–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YG, Cha J, Chandrasegaran S. Hybrid restriction enzymes: zinc finger fusions to Fok I cleavage domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1156–1160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Remy S, et al. Zinc-finger nucleases: a powerful tool for genetic engineering of animals. Transgenic Res. 2010;19:363–371. doi: 10.1007/s11248-009-9323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geurts AM, et al. Knockout rats via embryo microinjection of zinc-finger nucleases. Science. 2009;325:433. doi: 10.1126/science.1172447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant AJ, Dickens JC. Functional characterization of the octenol receptor neuron on the maxillary palps of the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bohbot JD, Dickens JC. Characterization of an enantioselective odorant receptor in the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu T, et al. Odor coding in the maxillary palp of the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1533–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones WD, Cayirlioglu P, Kadow IG, Vosshall LB. Two chemosensory receptors together mediate carbon dioxide detection in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;445:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature05466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghaninia M, Ignell R, Hansson BS. Functional classification and central nervous projections of olfactory receptor neurons housed in antennal trichoid sensilla of female yellow fever mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:1611–1623. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05786.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghaninia M, Larsson M, Hansson BS, Ignell R. Natural odor ligands for olfactory receptor neurons of the female mosquito Aedes aegypti: use of gas chromatography-linked single sensillum recordings. J Exp Biol. 2008;211:3020–3027. doi: 10.1242/jeb.016360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gouck HK. Host preferences of various strains of Aedes aegypti and Aedes simpsoni as determined by an olfactometer. Bull World Health Org. 1972;47:680–683. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster WA, Takken W. Nectar-related vs. human-related volatiles: behavioural response and choice by female and male Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) between emergence and first feeding. Bull Entomol Res. 2004;94:145–157. doi: 10.1079/ber2003288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dogan EB, Ayres JW, Rossignol PA. Behavioural mode of action of deet: inhibition of lactic acid attraction. Med Vet Entomol. 1999;13:97–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.1999.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ditzen M, Pellegrino M, Vosshall LB. Insect odorant receptors are molecular targets of the insect repellent DEET. Science. 2008;319:1838–1842. doi: 10.1126/science.1153121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Syed Z, Leal WS. Mosquitoes smell and avoid the insect repellent DEET. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13598–13603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805312105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu C, et al. Distinct olfactory signaling mechanisms in the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae. PLoS Biol. 2010;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bohbot JD, Dickens JC. Insect repellents: Modulators of mosquito odorant receptor activity. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pellegrino M, Steinbach N, Stensmyr MC, Hansson BS, Vosshall LB. A natural polymorphism alters odour and DEET sensitivity in an insect odorant receptor. Nature. 2011;478:511–514. doi: 10.1038/nature10438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee YS, Kim SH, Montell C. Avoiding DEET through insect gustatory receptors. Neuron. 2010;67:555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hallem EA, Carlson JR. Coding of odors by a receptor repertoire. Cell. 2006;125:143–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carey AF, Wang G, Su CY, Zwiebel LJ, Carlson JR. Odorant reception in the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Nature. 2010;464:66–71. doi: 10.1038/nature08834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silbering AF, et al. Complementary function and integrated wiring of the evolutionarily distinct Drosophila olfactory subsystems. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13357–13375. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2360-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.