Abstract

Background

To induce consumers to purchase healthier foods and beverages, some policymakers have suggested special taxes or labels on unhealthy products. The potential of such policies is unknown.

Purpose

In a controlled field experiment, researchers tested whether consumers were more likely to purchase healthy products under such policies.

Methods

From October to December 2011, researchers opened a store at a large hospital that sold a variety of healthier and less-healthy foods and beverages. Purchases (N=3680) were analyzed under five conditions: a baseline with no special labeling or taxation, a 30% tax, highlighting the phrase “less healthy” on the price tag, and combinations of taxation and labeling. Purchases were analyzed in January–July 2012, at the single-item and transaction levels.

Results

There was no significant difference between the various taxation conditions. Consumers were 11 percentage points more likely to purchase a healthier item under a 30% tax (95% CI=7%, 16%, <0.001) and 6 percentage points more likely under labeling (95% CI=0%, 12%, p=0.04). By product type, consumers switched away from the purchase of less-healthy food under taxation (9 percentage points decrease, p<0.001) and into healthier beverages (6 percentage point increase, p=0.001); there were no effects for labeling. Conditions were associated with the purchase of 11–14 fewer calories (9%–11% in relative terms) and 2 fewer grams of sugar. Results remained significant controlling for all items purchased in a single transaction.

Conclusions

Taxation may induce consumers to purchase healthier foods and beverages. However, it is unclear whether the 15%–20% tax rates proposed in public policy discussions would be more effective than labeling products as less healthy.

Introduction

A recent IOM report found that two thirds of adults and one third of children were overweight or obese, with associated costs comprising 21% ($190.2 billion) of annual healthcare expenditure in the U.S.1 Policies aimed at labeling menus with the number of calories in each item have thus far generally failed to significantly reduce calorie consumption,2–5 leaving policymakers and public health officials in a quandary regarding finding effective tools to reduce obesity.

As an alternative method of changing behavior, taxing unhealthy items, particularly sugar-sweetened beverages, is under consideration in several states. These proposals are based on the cigarette excise tax,6 which is credited with a substantial reduction in smoking rates.7–11 In most cases, the proposal is for a $0.01 per ounce excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages, or approximately 15%–20% for a 20-ounce soft drink.12 Such proposals are under consideration in nine states, but have been stalled or rejected in five others since 2009.13,14

Internationally, Denmark, France, and Hungary began implementing taxes on foods and beverages with low nutritional value in 2011.15–17 Following implementation, Denmark found a 4%–5% decline in sales of butter and cookies18 but repealed its tax on concern that residents had avoided taxation by purchasing groceries in neighboring Germany.19 Research has not produced consistent findings on whether taxes encourage consumption of healthier foods and beverages,20–25 and if so, what tax rate is necessary to substantially reduce obesity rates.23,24,26–28

Prior studies in this area are lacking in several regards. Many studies suggest that taxation of less-healthy items may lead to reduced consumption and weight loss,26,27,29–33 a lower incidence of disease,34–36 and substantial state revenue,29,37 although results are not uniform.24,38 Such work has been limited by the use of secondary data.22, 26–28 These studies rely on price differences across localities that could vary for any number of reasons, thereby making it difficult to directly ascertain the impact of a price change that would result from actual implementation of a tax.

Many of these studies also only consider food or beverages individually, rather than substitution between them.20,21,24,27,31–44 Given that food and beverage choices are often made jointly, this lacking also misses the full picture. Other studies fail to consider alternative policy options to taxation.20,21,24,27,31–44 Finally, many studies are simple laboratory studies, lacking the real-world complexity of food choice as it plays out in the real world.

The environment in which taxes are presented may also matter, a consideration that many other studies ignore. Taxes that are included in the posted price 39 and those that identify the reason for the tax 40 may reduce consumption by more than taxes added at checkout, even when the monetary effect is equivalent. Considering such possible behavioral responses has been applied to encourage tobacco cessation 40 and retirement savings,41 but not healthier eating.

The study presented here overcomes many of these past limitations. In a controlled field experiment, researchers sought to better understand the potential for taxation and labeling to induce consumers to purchase both healthier foods and beverages, in two dimensions. First, consumer purchasing patterns were compared under a variety of tax scenarios, as compared with a baseline of no tax scenario. Second, the differential effect of taxation on purchases of healthier items was considered as compared to and combined with highlighting less-healthy foods and beverages with the phrase “less healthy.” Comparing multiple policy contexts in a real-world field experiment looking at actual purchases is a substantial improvement over past research.

Methods

Approach

Researchers opened a small store, often referred to as a bodega or corner store, at Bellevue Hospital Center, the largest public hospital in New York City, during October–December 2011. The hospital caters to low-income, minority, and immigrant populations,45 who have a higher burden of healthcare needs than the general population.46 The store was located in the outpatient area, open to anyone who entered, and consumers used their own money to purchase items. Hours were 8am–4pm, weekdays. Signs notified participants that entrance to the market signified consent to participate in a research study, and they were asked when leaving the store to complete a short survey for $2.00. Analysis was conducted in January–July 2012. The study was approved by the IRBs of New York University School of Medicine and Bellevue Hospital Center.

Researchers surveyed local stores and set inventory and pretax prices similar to those in the surrounding community. Bodegas visited were located on the two nearest avenues, within approximately 0.75 miles south and 0.50 miles north. Because many stores carried almost exclusively unhealthy items, they added logical healthier alternatives; for example, baked potato chips as an alternative to regular potato chips. They also added some healthier items, such as fresh fruit and trail mix, despite their absence in local corner stores. All items except for fresh fruit carried the federally mandated nutrition facts panel, and researchers recorded the total nutrient content of each item. Healthier and less-healthy items were located near each other, so that individuals could easily see healthier alternatives. In total, there were 34 healthier and 45 less-healthy items offered, at an average pretax price of $0.90 (or $0.99 excluding fresh fruit) and $0.98, respectively.

Definition of Healthier Items

Researchers assessed each item by three healthy snack standards adopted by states for use in schools or used in prior research. The criteria were from: Alabama (≤6.5 g total fat, <30 g carbohydrates; <360 mg sodium; beverage size ≤12 oz generally or ≤16 oz for water and milk; ≥5% daily value of vitamin A, vitamin C, iron, calcium, or fiber)42; California (≤35% of calories from fat, except for nuts and seeds; ≤10% calories from saturated fat; ≤35% total weight from sugar, except for fruits and vegetables; and beverages limited to milk, water, and ≥50% fruit juice with no added sweeteners)43; and prior research studies (≤150 calories for food, ≤50 calories for beverages, ≤30% calories from fat, and ≤35% total weight from sugar).44 Alabama and California are the only states with such standards, and no federal guidelines exist. Researchers defined items that met at least two of the three standards in their entirety as healthier, and other items as less healthy.

Conditions

Researchers tested five conditions: (1) a baseline condition with no special labeling or taxation; (2) highlighting “less healthy” in red capital letters on the price tag, with a red box drawn around it; (3) a 30% non-itemized tax on less-healthy items (i.e., the price listed was simply 30% higher than in the baseline condition); (4) a 30% non-itemized tax on less-healthy items plus highlighting (as in Condition 2); and (5) a 30% itemized, explicit tax on less-healthy items (i.e., the price listed was 30% higher, and the reason why was stated “30% less healthy tax = $0.33”) plus highlighting with the “less healthy” signage (Appendix A, available online at www.ajpmonline.org). A 30% tax was chosen to test whether individuals would choose healthier items in scenarios of extreme taxation. If these results were significant, then future research could address the optimal tax; but if a 30% tax did not affect purchasing behavior, then neither would lower tax rates. The baseline condition appeared twice, once for 5.5 days at the beginning of the study and once for 3 days in the middle of the study, but otherwise the conditions were presented sequentially in the order listed above. Each condition was tested for 8–9 days, for a total of 41.5 days.

Data Analysis

Researchers designed statistical methods to reflect assumptions about information that policymakers would desire before making a decision to potentially highlight or tax less-healthy foods and beverages. First, researchers assumed that policymakers would want to know whether purchases of healthier items increased under highlighting or taxation policies. Therefore, researchers analyzed the association between various conditions and an individual’s purchase of a healthier item at both the single-item and transaction levels (considering all purchases made by individuals at the same time).

The primary modeling framework was a logistic regression, with the dependent variable an indicator of whether an individual would purchase a healthier item. The key independent variables of interest were dummy variables for each condition, or in alternate specifications, dummy variables for the presence of highlighting only (Condition 2) and any tax (Conditions 3–5). Other independent variables included dummy variables for day of the week (each of Monday–Friday); time of day (morning [8am–12pm]; early afternoon [12pm–2pm]; late afternoon [2pm–4pm]); non-employees (patients and family members) vs employee (identified by whether the individual wore a mandatory hospital identification badge); and a continuous variable for number of items in the transaction. SEs were clustered at the transaction level, with a transaction defined as all items purchased by one individual at one time.

To translate each coefficient into a probability-like measure, researchers computed the partial derivative of purchasing a healthier item with respect to each independent variable, evaluated for each purchase. The result over all observations was averaged, to obtain an average marginal effect. A Wald test for equality of the coefficients across conditions was conducted.

Second, researchers assumed that policymakers would want to better understand whether the effects were similar for beverages vs food. Therefore, researchers used a multinomial logistic model where the outcome was one of four possibilities: healthier beverage, less-healthy beverage, healthier food, or less-healthy food. In this framework, coefficients indicate the relative shift in purchases between categories, with the sum across outcomes always equal to zero. A negative coefficient would indicate a shift in purchases away from one category, and a positive coefficient would indicate a shift in purchases toward another category. The independent variables were the same as for the univariate logistic model.

Third, researchers assumed that policymakers would want information on potential changes in nutrition associated with highlighting and taxation. Accordingly, using the same independent variables, ordinary least-squares regressions were considered, where the dependent variable was a measure of nutrition (calories; total fat; fat/calories (%); total carbohydrates; sodium; or sugars in an item). Finally, researchers considered whether the various conditions were associated with substitution into less-expensive (healthier or less-healthy) items, by considering the pretax price of an item as the dependent variable, and dummy variables for each condition as independent variables. These regressions were considered at both the individual and transaction levels. Robust SEs were used.

When estimating the effects of the various conditions on the probability of purchasing a healthier beverage, there was concern about potential bias from individuals who had decided to purchase water before entering the bodega. Bottled water is a popular beverage, and researchers could not distinguish between individuals who wanted water and those who were induced to purchase it because of taxation or highlighting. Accordingly, each model was rerun, first excluding transactions for water only and then excluding employees (who made up 93% of water-only transactions). Analyses were conducted using Stata.

Power

Researchers did not know the proportion of healthier items that would be sold in the baseline condition. However, for results to be policy relevant, researchers assumed that the highlighting and taxation conditions would need to be associated with a 10% increase in purchases of healthier items. Therefore, to be conservative, the minimum number of observations (90% power, two-sided alpha of 5%) was estimated to detect all possible combinations of interest (increase in purchases of healthier items from 40% to 50%, from 50% to 60%, and so on). The most stringent power requirements necessitated 544 observations per condition, which were sufficient to detect an increase in purchases of healthier items from 45% in the baseline condition to 55% in the highlighting and tax conditions.

Results

Appendix B (available online at www.ajpmonline.org) presents summary statistics. Individuals bought a total of 3680 items across 2151 transactions, and exceeded the criteria for 90% power. There were significant differences across days of the week and times of day, but no differences on whether the purchase was made by an employee. There was a significant effect of the various conditions on percentage of healthy times chosen, ranging from 47.2% of purchases in the baseline condition (Condition 1) to 60.1% of purchases in the itemized, explicit tax plus highlighting condition (Condition 5; p<0.001 across conditions). Beverages accounted for about one third of purchases, and the percentage of beverage purchases was not different across conditions. Healthier items that were sold cost $0.14 less and had 107 fewer calories than less-healthy items. Six percent of transactions were for water only.

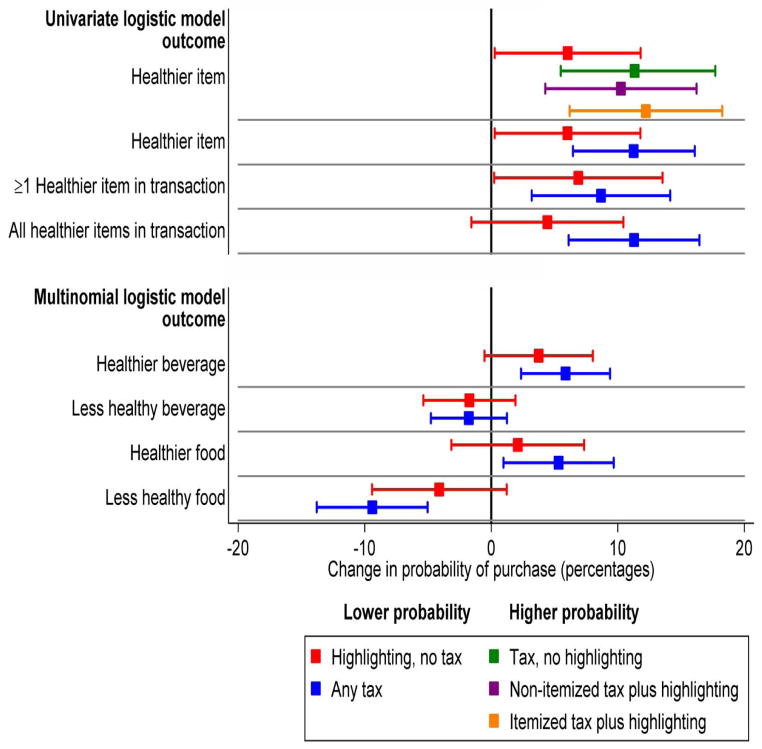

Appendix A (available online at www.ajpmonline.org) shows the association between various conditions and the tendency to purchase a healthier item, controlling for other variables. The first model shows that the highlighting-only condition (red line in Figure 1) increased the probability of purchasing a healthy item by six percentage points over the control condition (average marginal effect [AME]=6.04%, 95% CI=0.28%, 11.80%, p=0.04). Each of the 30% tax conditions (green, purple, and orange lines in Figure 1) increased the probability of purchasing of a healthier item by 10–12 percentage points (p<0.001), and were not significantly different from each other (p on Wald test=0.82). Therefore, for the rest of the analysis, all of the tax conditions were considered together. Individuals were 11 percentage points more likely to purchase a healthier item under any tax condition (AME=11.26%, 95% CI=6.45%, 16.08%, p<0.001; second model, blue line in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Purchases of healthier items under highlighting and tax conditions

The coefficients between the baseline, highlighting-only, and any-tax conditions were significantly different from each other (p <0.001 on Wald test), as were the coefficients between the highlighting-only and tax conditions (p=0.03 on Wald test). Overall, individuals had a 47% probability of purchasing a healthier item in the baseline condition (95% CI=43%, 52%); 54% in the highlighting-only condition (95% CI=49%, 58%); and 59% in the tax conditions (95% CI=56%, 61%; not shown). Similar results were found for the tendency to purchase at least one healthier item and all healthier items in the transaction (Figure 1). Additional analyses for non-water-only and public versus employee transactions yielded similar results (not shown).

The multinomial logistic framework (Figure 1) suggested that taxation was associated with individuals choosing fewer less-healthy foods (AME= −9.41%, 95% CI= −13.80%, −5.03%, p<0.001) and more of the healthier beverages (AME=5.87%, 95% CI=2.36%, 9.38%, p=0.001). Effects for healthier foods (AME=5.32%, p=0.017) and less-healthy beverages (AME= −1.78%, p=0.25) were smaller. For highlighting without any tax, the results were in the expected direction, but were not significant.

Table 1 reports the effect on nutrition and price. The highlighting condition without any tax (Column 1) was significant for an 11-calorie decrease (coefficient= −11.49, 95% CI= −20.91, −2.0, p=0.02). Coefficients were similar across taxation conditions (not shown), with any tax significant for a 14-calorie decrease (coefficient= −13.91, 95% CI= −21.73, −6.08, p<0.001) (Column 1). Similar effects were found for sugars (1.5 g–2.0 g reduction; Column 4). No significant effect was found for total fat, fat/calories, sodium, or pretax price paid for a product, overall and in subsets of food only and beverage only.

Table 1.

Price and Nutrition Under Highlighting and Tax Conditionsa

| Dependent-Variable | Calories (kcal) | Total Fat (g) | Sodium (g) | Sugars (g) | Pretax price (¢) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Column | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| Item-Level Analysis | |||||

| Highlighting, no tax | −11.44* | −0.25 | −0.43 | −1.57* | −0.69 |

| p-Value (95% CI) | 0.017 (−20.86, − 2.03) | 0.44 (−0.89,0.38) | 0.95 (−12.77, 11.91) | 0.032 (−3.00, −0.13) | 0.75 (−4.92, 3.54) |

| Any tax | −13.91*** | −0.28 | −2.20 | −1.97*** | −3.08 |

| p-Value (95% CI) | <0.001 (−21.73, − 6.08) | 0.30 (−0.82,0.25) | 0.66 (−12.09, 7.69) | <0.001 (−3.10, −0.84) | 0.080 (−6.53, 0.37) |

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| F | 3.56 | 3.06 | 2.56 | 3.09 | 4.10 |

| n | 3680 | 3680 | 3680 | 3680 | 3680 |

|

| |||||

| Transaction-Level Analysis | |||||

| Highlighting, no tax | −17.77* | −0.31 | −0.79 | −2.50* | −2.61 |

| p-Value (95% CI) | 0.029 (−33.66, − 1.88) | 0.57 (−1.38, 0.76) | 0.94 (−21.82, 20.24) | 0.047 (−4.96, −0.04) | 0.47 (−9.75, 4.52) |

| Any tax | −22.59** | −0.39 | −3.33 | −3.30** | −6.22* |

| p-Value (95% CI) | 0.001 (−36.17, − 9.01) | 0.41 (−1.31, 0.54) | 0.70 (−20.45, 13.79) | 0.001 (−5.27, −1.33) | 0.040 (−12.16, − 0.27) |

| R2 | 0.64 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.73 |

| F | 94.80 | 31.46 | 45.50 | 30.08 | 199.34 |

| n | 2151 | 2151 | 2151 | 2151 | 2151 |

Note: Boldface indicates significance.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

All models control for day of week, time of day, and number of items in transaction.

Similar results were found at the transaction level, with a 7 percentage point increase in purchases of healthier items under the highlighting-only condition (AME= 7.12%, 95% CI=1.11%, 13.12%, p=0.02), and a 9 percentage point increase under the taxation conditions (AME=9.30%, 95% CI=4.33%, 14.26%, p<0.001). Similarly, transactions contained significantly fewer calories and sugars under each of highlighting and taxation, with stronger results under taxation (Table 1, Columns 1 and 4). The pretax price of the transaction was 6¢ lower under taxation (p=0.04; Table 1, Column 5).

Discussion

In a controlled field experiment with a high-need population, both the imposition of a 30% tax on less-healthy items and highlighting items as less healthy were associated with healthier purchases by consumers. Coefficients were generally larger and more significant for taxation conditions. The results are generally consistent with prior work that examines price elasticity of unhealthy food purchases, according to a recent review study.22 That review found an elasticity for soft drinks of 0.79 (95% CI=0.33, 1.24) and for sweets/sugars of 0.34 (95%=0.14, 0.53), whereas the elasticity in the current study for less-healthy items was 0.38 (95% CI=0.22, 0.54) (11.26% AME for the imposition of any tax/30% tax rate in Figure 1).22

The results also contrast with studies on calorie labeling, which generally have found little to no association between labeling menus with the number of calories in an item and number of calories purchased.3–5 A decline of 11–14 calories per item was found, or 8.9%–10.9% in relative terms, and 18–23 calories per transaction. If these results held at a larger scale, for meals rather than snacks, or repeatedly over time, the public health impact could become meaningful.

For policymakers considering the potential of nutritional labeling, it is noteworthy that highlighting the word “less healthy” in large red letters on the price tag was associated with behavior changes (7 percentage point increase in purchases of healthier items), although to a lesser extent than taxation (12 percentage point increase). One possibility is that individuals already knew which items were less healthy, and benefited less from the additional information of highlighting. Still, because the effect was significant, consumers may have found the words “less healthy” to be more helpful than detailed nutrition labels, which were always available. This is consistent with the recent IOM Committee examining front-of-package food labeling, which suggested a streamlined label that quickly and easily conveyed nutrition information without numbers.47 Indeed, prior work on calorie labeling has suggested that consumers may not understand the difference between 300 versus 400 calories in the context of their overall daily nutritional requirements.48

A 30% tax rate was chosen to consider behavior change in extreme scenarios, and the results are consistent with past work on consumer sensitivity to price changes.22,24 However, it is unclear whether highlighting or taxation would dominate at a lower, more realistic tax rate. For example, proposed soda taxes usually are in the neighborhood of of $0.01/ounce, or about 15%–20% of purchase price in popular sizes.12 Multiplying the estimated coefficients on taxation by 0.50–0.75 (15%–20% proposed tax/30% tax in the scenarios) suggests that highlighting the word “less healthy” might have an effect similar to that of taxation.

Phrased another way, linear interpolation of the results would suggest that tax rates ≥16% would be required to have a stronger effect on behavior than highlighting (6.03/11.26*30% in Figure 1). Such a strict interpretation would be overanalyzing the results, particularly as consumers may not respond linearly to changes in tax rates.49 More research is necessary to discern the potential benefits of taxes in the fight against obesity.

Limitations

It was unknown whether the same individual shopped at the bodega more than once, so it is possible that the results over-represented certain individuals. However, the bodega was located in a wing of Bellevue Hospital Center where scheduled outpatient visits occurred. These visits tend to be spaced out, and researchers did not casually observe substantial numbers of repeat customers. Second, although pretax prices were competitive with those at local bodegas, it is possible that consumers seeing a high after-tax price on less-healthy items chose to purchase the same item elsewhere. However, volume was similar across conditions (Appendix A, available online at www.ajpmonline.org).

Third, some studies suggest that an additional baseline condition of equal length would have been helpful to confirm the current results.24 Fourth, Bellevue Hospital Center primarily serves uninsured and minority patients, who may behave differently from the broader population. This setting was chosen in part because obesity disproportionately affects the poor,50 who are over-represented at Bellevue. Finally, the location of the bodega inside a hospital may have led consumers to be somewhat more nervous or health-conscious when making decisions, and therefore more receptive to the experimental conditions.50

Conclusion

Although taxes and labeling are not the single answer to influence obesity, these public policies may induce consumers to purchase healthier foods and beverages. It is unclear whether proposed tax rates in public policy discussions would be more effective than highlighting overall nutritional content alone.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grant UL1RR029893, NCRR, and R01HL095935, NHLBI, NIH. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the paper. The authors thank Jesse Morgan Hills, MPH, New York University School of Medicine, for his support in project coordination and research.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Glickman D, Parker L, Sim L, Cook H, Miller E. Accelerating progress in obesity prevention: solving the weight of the nation. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harnack LJ, French SA, Oakes JM, Story MT, Jeffery RW, Rydell SA. Effects of calorie labeling and value size pricing on fast food meal choices: Results from an experimental trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5(5):63. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elbel B, Kersh R, Brescoll V, Dixon L. Calorie labeling and food choices: a first look at the effects on low-income people in New York City. Health Aff. 2009;28(6):w1110–21. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elbel B, Gyamfi J, Kersh R. Child and adolescent fast-food choice and the influence of calorie labeling: a natural experiment. Int J Obes. 2011;35(4):493–500. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vadiveloo M, Dixon L, Elbel B. Consumer purchasing patterns in response to calorie labeling legislation in New York City. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2011;8(1):51. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frieden T, Dietz W, Collins J. Reducing childhood obesity through policy change: acting now to prevent obesity. Health Aff. 2010;29(3):357–63. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fishman PA, Ebel BE, Garrison MM, Christakis DA, Wiehe SE, Rivara FP. Cigarette tax increase and media campaign cost of reducing smoking-related deaths. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams EK, Markowitz S, Kannan V, Dietz PM, Tong VT, Malarcher AM. Reducing prenatal smoking: the role of state policies. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang B, Cohen J, Ferrence R, Rehm J. The impact of tobacco tax cuts on smoking initiation among Canadian young adults. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(6):474–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CDC. Reducing tobacco use: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta GA: DHHS; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.IOM. Ending the tobacco problem: a blueprint for the nation. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brownell K, Farley T, Willett W, et al. The public health and economic benefits of taxing sugar-sweetened beverages. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1599–605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0905723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanford D. Anti-obesity soda tax fails as lobbyists spend millions: retail. Bloomberg: Businessweek; 2010. Mar 13, www.businessweek.com/news/2012-03-13/anti-obesity-soda-tax-fails-as-lobbyists-spend-millions-retail. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity. Legislation trends: Sugar-sweetened beverages/taxes. www.yaleruddcenter.org/legislation/legislation_trends.aspx.

- 15.Villanueva T. European nations launch tax attack on unhealthy foods. Can Med Assoc J. 2011;183(17):E1229–30. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mytton O, Clarke D, Rayner M. Taxing unhealthy food and drinks to improve health. BMJ. 2012;344:E2931. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.République Française, Ministère du Budget, des Comptes Publics, et de la Réforme de L’État. Contributions sur les boissons et préparations liquides pour boissons sucrées et édulcorées: contributions indirectes. Circulaire du. 2012 Jan 24; NOR: BCRD 1202351C. circulaire.legifrance.gouv.fr/pdf/2012/01/cir_34494.pdf.

- 18.Nielsen ScanTrak Dagligvareindeks. Volumen salg I 100 kg. 2011 Jul 17 – 2012 Jul 15.

- 19.Pedersen TS, Jensen K, Rørvig M, Legarth M, Mikkelsen B. B 3 Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om afskaffelse af afgiften på mættet fedt (fedtafgiften) www.ft.dk/samling/20121/beslutningsforslag/b3/index.htm.

- 20.Barry CL, Niederdeppe J, Gollust SE. Taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages: results from a 2011 national public opinion survey. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(2):158–63. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorfman L. Talking about sugar sweetened-beverage taxes: will actions speak louder than words? Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(2):194–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andreyeva T, Long M, Brownell K. The impact of food prices on consumption: a systematic review of research on the price elasticity of demand for food. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):216–22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.151415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epstein LH, Dearing KK, Roba LG, Finkelstein E. The influence of taxes and subsidies on energy purchased in an experimental purchasing study. Psychol Sci. 2010;21(3):406–14. doi: 10.1177/0956797610361446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein L, Jankowiak N, Nederkoorn C, et al. Experimental research on the relation between food price changes and food-purchasing patterns: a targeted review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(4):789–809. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.024380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jue JJ, Press MJ, McDonald D, et al. The impact of price discounts and calorie messaging on beverage consumption: A multi-site field study. Prev Med. 2012;55(6):629–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith T, Lin B, Lee J. Taxing caloric sweetened beverages: potential effects on beverage consumption, calorie intake, and obesity. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Economic Research Report No ERR–100 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sturm R, Powell L, Chriqui J, Chaloupka F. Soda taxes, soft drink consumption, and children’s body mass index. Health Aff. 2010;29(5):1052–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powell L, Chaloupka F. Food prices and obesity: evidence and policy implications for taxes and subsidies. Milbank Q. 2009;87:229–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim D, Kawachi I. Food taxation and pricing strategies to “thin out” the obesity epidemic. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(5):430–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eyles H, Ni Mhurchu C, Nghiem N, Blakely T. Food pricing strategies, population diets, and non-communicable disease: a systematic review of simulation studies. PLoS Med. 2012;9(12):e1001353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brownell K, Frieden T. Ounces of prevention – the public policy case for taxes on sugared beverages. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(18):1805–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0902392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finkelstein E, Zhen C, Nonnemaker J, Todd J. Impact of targeted beverage taxes on higher- and lower-income households. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):2028–34. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dharmasena S, Capps OJ. Intended and unintended consequences of a proposed national tax on sugar-sweetened beverages to combat the U.S. obesity problem. Health Econ. 2012;21(6):669–94. doi: 10.1002/hec.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, Coxson P, Shen Y, Goldman L, Bibbins-Domingo K. A penny-per-ounce tax on sugar-sweetened beverages would cut health and cost burdens of diabetes. Health Aff. 2012;31(1):199–207. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall T. Exploring a fiscal food policy: the case of diet and ischaemic heart disease. BMJ. 2000;320(7230):301–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7230.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mytton O, Gray A, Rayner M, Rutter H. Could targeted food taxes improve health? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(8):689–94. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.047746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andreyeva T, Chaloupka F, Brownell K. Estimating the potential of taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages to reduce consumption and generate revenue. Prev Med. 2011;52(6):413–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schroeter C, Lusk J, Tyner W. Determining the impact of food price and income changes on body weight. J Health Econ. 2008;27(1):45–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chetty R, Looney A, Kroft K. Salience and taxation: theory and evidence. Am Econ Rev. 2009;99(4):1145–77. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Decicca P, Kenkel D, Mathios A, Shin Y, Lim J. Youth smoking, cigarette prices, and anti-smoking sentiment. Health Econ. 2008;17(6):733–49. doi: 10.1002/hec.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carroll G, Choi J, Laibson D, Madrian B, Metrick A. Optimal defaults and active decisions. Q J Econ. 2009;124(4):1639–74. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2009.124.4.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alabama State Board of Education. Alabama’s healthy snack standards for food and beverages at school. 2005 cnp.alsde.edu/NutritionPolicy/AlaHealthySnackStandards.pdf.

- 43.State of California. The Pupil Nutrition, Health, and Achievement Act of 2001. SB 19. Article 2.5. Section 49430.

- 44.French S, Hannan P, Harnack L, et al. Pricing and availability intervention in vending machines at four bus garages. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(Suppl 1):S29–33. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181c5c476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCarthy D, Mueller K. The New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation: Transforming a public safety net delivery system to achieve higher performance. The Commonwealth Fund. Commission on a High Performance Health System. 2008 Oct; [Google Scholar]

- 46.New York State Department of Health. New York State Minority Health Surveillance Report. 2007 Sep; www.health.ny.gov/statistics/community/minority/docs/surveillance_report_2007.pdf.

- 47.Wartella E, Lichtenstein A, Yaktine A, Nathan R, editors. Front-of-package nutrition rating systems and symbols: promoting healthier choices. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elbel B. Consumer estimation of recommended and actual calories at fast food restaurants. Obesity. 2011;19(10):1971–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finkelstein A. E-Z Tax: Tax salience and tax rates. Q J Econ. 2009;124(3):969–1010. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ogden C, Lamb M, Caroll M, Flegal K. Obesity and socioeconomic status in adults: U.S. 2005–2008. NCHS data brief No. 50. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.