Abstract

Context

In response to national efforts to improve quality of care, policymakers and health care leaders have increasingly turned to quality improvement collaboratives (QICs) as an efficient approach to improving provider practices and patient outcomes through the dissemination of evidence-based practices. This article presents findings from a systematic review of the literature on QICs, focusing on the identification of common components of QICs in health care and exploring, when possible, relations between QIC components and outcomes at the patient or provider level.

Methods

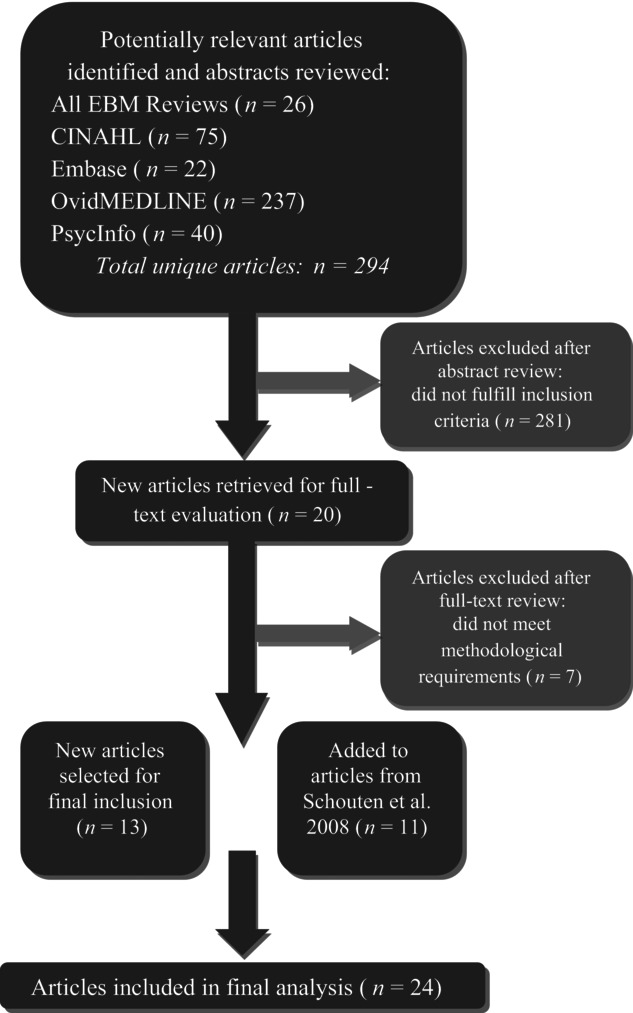

A systematic search of five major health care databases generated 294 unique articles, twenty-four of which met our criteria for inclusion in our final analysis. These articles pertained to either randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental studies with comparison groups, and they reported the findings from twenty different studies of QICs in health care. We coded the articles to identify the components reported for each collaborative.

Findings

We found fourteen crosscutting components as common ingredients in health care QICs (e.g., in-person learning sessions, phone meetings, data reporting, leadership involvement, and training in QI methods). The collaboratives reported included, on average, six to seven of these components. The most common were in-person learning sessions, plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles, multidisciplinary QI teams, and data collection for QI. The outcomes data from these studies indicate the greatest impact of QICs at the provider level; patient-level findings were less robust.

Conclusions

Reporting on specific components of the collaborative was imprecise across articles, rendering it impossible to identify active QIC ingredients linked to improved care. Although QICs appear to have some promise in improving the process of care, there is great need for further controlled research examining the core components of these collaboratives related to patient- and provider-level outcomes.

Keywords: quality improvement, health services research, organizational innovation, quality assurance, Breakthrough Series

Following the Institute of Medicine's influential report “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” which highlighted significant deficiencies in the quality of health care (IOM 2001), enormous emphasis has been placed on improving health care processes through the implementation of evidence-based practices (EBPs). As states and large organizations respond to calls to improve the quality of care, policymakers and health care leaders seek effective strategies to change provider practices and, ultimately, patient outcomes. Quality improvement collaboratives (QICs) and other multiorganization models used to improve the quality of care and implement evidence-based practices have become very popular. In behavioral health alone, through the National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare (NCCBH), thirty-five states are now using QICs to change health care provider practices (A. Salerno, personal communication, July 1, 2012). The federal government also is making significant investments in QICs. For example, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) recently called for applications for State Adolescent Treatment Enhancement and Dissemination grants totaling $30 million over three years (SAMHSA Bulletin 2012). These grants are intended to help states develop “learning laboratories” focused on shared provider experiences when implementing EBPs to improve outcomes for youth and families. Which features of these collaborative models are most important to predicting patient and provider outcomes are not well understood, however.

Policymakers are beginning to recognize that the minimalist training and consultation models typically used for large-scale rollouts of new quality improvement practices are insufficient and that without monitoring, feedback, and organizational support, new practices often do not succeed (Bond et al. 2009; Schoenwald and Hoagwood 2001; Schoenwald, Sheidow, and Letourneau 2004). The goal of our article is to update the literature on the QICs’ patient- and provider-level outcomes, to characterize how the common QIC components are reported in empirical outcome studies, and to identify, to the extent possible, the relationships between the QICs’ components and provider- and patient-level outcomes.

Theoretical Background

QICs in health care emerged after the publication of several papers highlighting the potential of continuous quality improvement (CQI) methods, originally developed for use in industry, to improve care processes in health care (e.g., Berwick 1989, 1996; Laffel and Blumenthal 1989). These approaches, which first gained popularity as a way to address manufacturing deficiencies, are now well integrated into a number of industries and management practices (Deming 1986; Ishikawa 1985; Juran 1951, 1964). CQI methods are based on the notion that ongoing data collection can be used to identify production deficiencies, which can then be targeted for improvement and reassessed (Deming 1986; Ishikawa 1985; Juran 1951, 1964). Inherent in this approach is the assumption that improvement is always possible and continuous and that workers intend to perform well (Berwick 1989; Deming 1986).

The multiorganizational quality improvement efforts that are the focus of this article emerged in part from the failures and perceived limitations of single-organization quality improvement efforts in health care. Perhaps the most widely used QIC approach in controlled outcome studies is the Breakthrough Series (BTS) collaborative developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI 2003; Kilo 1998), although there are many variations of this model (e.g., Ayers et al. 2005; Becker, Drake, and Bond 2011; Ebert et al. 2012; Mittman 2004; Øvretveit et al. 2002; Plsek 1997; Solberg 2005; Wilson, Berwick, and Cleary 2004). The BTS is designed as a specific model for achieving rapid, measureable, and sustained improvements, with the intention of weaving QI processes into the everyday work of QIC participants (Baker 1997; Kilo 1998). The BTS's components include formation of a planning group that decides on a target objective and identifies areas for change, pre-work from participants (e.g., identifying QI team members and roles and planning for necessary supports), in-person learning sessions during which teams learn clinical and QI approaches, and ongoing support (e.g., phone calls, visits, email, brief reports). Between learning sessions, participants engage in plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles during which they make small interventions and assess their impact (Kilo 1998).

Controlled studies also have investigated the Vermont Oxford Network's QICs for neonatal intensive care, which use the network's existing data infrastructure as a platform for CQI. This organization has implemented cross-site QICs that incorporate group training in QI methods, site visits, and self-studies (Plsek 1997). The network's QIC forms a local QI group, assesses organizations’ care processes and procedures, sets benchmarks through site visits by QIC participants to high-performing sites, finds strategies for improvement, experiments with implementing strategies, and assesses change (Horbar et al. 2001, 2004; Plsek 1997; Rogowski et al. 2001).

Our Study

Given the QICs’ promise and popularity, we need reliable evidence that they are effective for implementing innovations and improving the quality of care. While some evidence shows that QICs can change providers’ practices (Bundy 2006; Cretin, Shortell, and Keeler 2004; Young et al. 2006), reviews of health care QICs suggest that the positive effects of such models are limited (Mittman 2004; Schouten et al. 2008). In a systematic literature review, Schouten and colleagues (2008) examined the methodological quality and outcomes of nine controlled studies of health care QICs, the majority of which used matched controls or administrative data for comparison. Two studies had positive effects on study outcomes (i.e., infant mortality rates, patient pain prevalence); two studies found no differences; and the rest were mixed, with the positive effects limited to quality indicators or process of care variables, assessed through abstracts of medical records or administrative data (Schouten et al. 2008).

One major obstacle to synthesizing findings across studies of QICs is the variation in QIC models used, the types of outcomes targeted, and the varied detail with which components are described in scientific reports (Mittman 2004; Schouten et al. 2008; Solberg 2005). There also is little understanding of which components may be linked to positive process of care and patient outcomes (Mittman 2004; Schouten et al. 2008; Solberg 2005). Some evidence suggests that participants value contact with expert faculty, solicitation of staff perspectives, PDSA cycles, learning sessions, and an extranet where information is exchanged (Nembhard 2009). Similarly, Schouten, Grol, and Hulscher (2010) identified four core QIC processes: sufficient expert team support, effective multidisciplinary teamwork, the use of a model for improvement, and helpful collaborative processes. In particular, engagement in interorganizational learning and deliberate learning activities (e.g., PDSA, solicitation of staff ideas, staff education) appear to be important to improving performance indicators among QIC participants (Nembhard 2012; Nembhard and Tucker 2011). A synthesized examination of how the core components of QICs are described in the outcome literature, as well as an exploration of the links between specific components and positive outcomes across QIC outcome studies, could help the development of more effective QICs.

Regardless of the QIC model they used, the many approaches clearly showed similarities and differences, although each approach emphasized different components. In their initial systematic review, Schouten and colleagues (2008) concluded that QICs had little positive impact and a great need for better-designed studies. Our study updates their review with new controlled outcome studies. In addition, our review builds on recent research suggesting that certain QIC processes may be particularly important to improving performance (Nembhard 2009, 2012; Nembhard and Tucker 2011; Schouten, Grol, and Hulscher 2010). Specifically, the goals of this systematic review are to determine whether additional conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of QICs based on the published information and to characterize how core QIC structures and processes are described in the QIC outcome literature. We also looked for any possible relationships between these QIC components and provider- and patient-level outcomes.

Methods

We found the core components described in the existing outcome studies by reviewing the outcome studies with the comparison groups in Schouten and colleagues’ 2008 paper, as well as with additional studies with comparison groups published more recently. Using Schouten and colleagues’ methodology, we searched five major databases: All EBM Reviews (Cochrane DSR, ACP Journal Club, DARE, CCTR, CMR, HTA, and NHSEED), CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Embase, OvidMEDLINE, and PsycInfo. Because Schouten and colleagues reviewed articles published from January 1995 to June 2006, we concentrated on articles published from June 2006 to April 2012 (or more generally, 2006 to 2012 for databases that do not allow searches with month-specific date ranges) for any relevant articles not in the earlier review. We replicated Schouten and colleagues’ search process using the same two primary sets of search terms, the non-MeSH keywords “quality improvement collaborative” or “breakthrough and (series or project),” in combination with a set of MeSH terms (“organizational-innovation” or “models-organizational” or “cooperative-behavior”; “program-evaluation” or “total-quality-management” or “quality-assurance-health-care”; “health-services-research” or “regional-medical-programs”). Because their term “Organi?ation* near (collabor* or participa*)” did not map to any existing MeSH headings, we omitted it from our search.

Our inclusion criteria for this systematic review were that articles had to be peer reviewed, written in English, and either randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental studies with a comparison group. In order to define QIC components, we searched the theoretical literature (Ayers et al. 2005; Becker et al. 2011; Ebert et al. 2012; Kilo 1998; Mittman 2004; Øvretveit et al. 2002; Plsek 1997) and more recent research on QIC processes (e.g., Nembhard 2009; Schouten, Grol, and Hulscher 2010), and we reviewed the definition used by Schouten and colleagues (2008). We then conducted informational interviews with a subset of QICs purveyors in order to elicit more detail.

Our study defines QICs as organized, structured group learning initiatives in which the organizers took the following steps: (1) convened multidisciplinary teams representing different levels of the organization; (2) focused on improving specific provider practices or patient outcomes; (3) included training from experts in a particular practice and/or the quality improvement methods; (4) provided a model for improvement with measurable targets, data collection, and feedback; (5) used multidisciplinary teams in active improvement processes in which they implemented “small tests of change” or engaged in PDSA activities; and (6) employed structured activities and opportunities for learning and cross-site communication (e.g., in-person learning sessions, phone calls, email listservs) (Ayers et al. 2005; Becker et al. 2011; Ebert et al. 2012; Kilo 1998; Mittman 2004; Øvretveit et al. 2002; Plsek 1997; Solberg 2005; Wilson, Berwick, and Cleary 2004).

Two of us (Laura Hill and Erum Nadeem) reviewed all the abstracts generated by the initial search to select articles that merited a full-text review. We also reviewed each article retrieved to determine whether it met our final inclusion criteria. In the event of a discrepancy, or if inclusion was unclear, we conferred with Sarah Horwitz, Kimberly Hoagwood, and Serene Olin to make a final determination.

Once we had decided on the articles, we coded each, using a standardized table to summarize the study's details (e.g., topics, study design, setting, sample, QIC components). A primary coder (Laura Hill or Erum Nadeem) was assigned to each article, and a secondary coder reviewed the primary coder's work. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Results

Literature Search

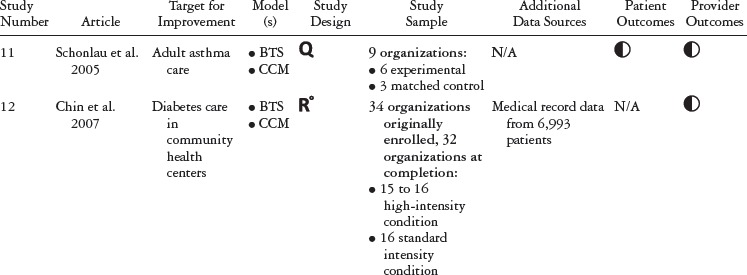

Our initial search generated 294 unique articles published between January 2006 and April 2012 (see figure 1). After reviewing these articles’ abstracts, we determined that twenty met the criteria for a full-text review. After the full-text review, thirteen met the criteria for final inclusion. These articles were published between 2006 and 2010. Adding these articles to those studied by Schouten and colleagues (2008) produced a total of twenty-four articles covering twenty different studies (five RCTs and fifteen with nonrandomized comparison groups) published from 2001 to 2010 (see table 1). The QICs in these studies covered a range of health and health care topics, many focusing on chronic conditions.

FIGURE 1.

Article selection process.

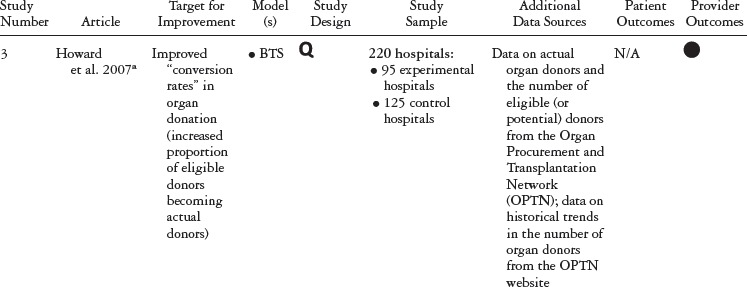

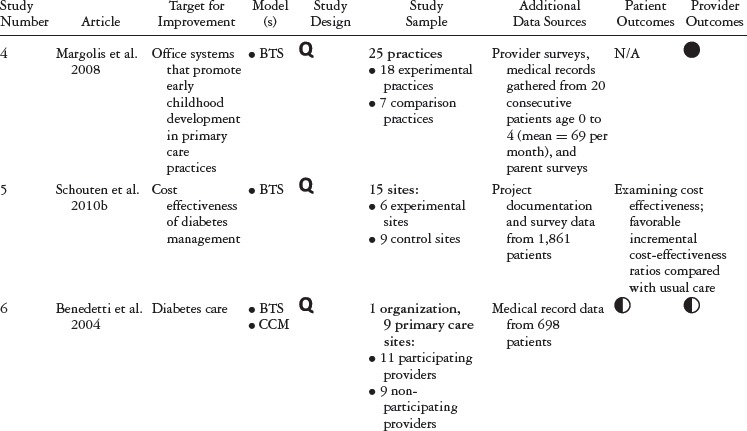

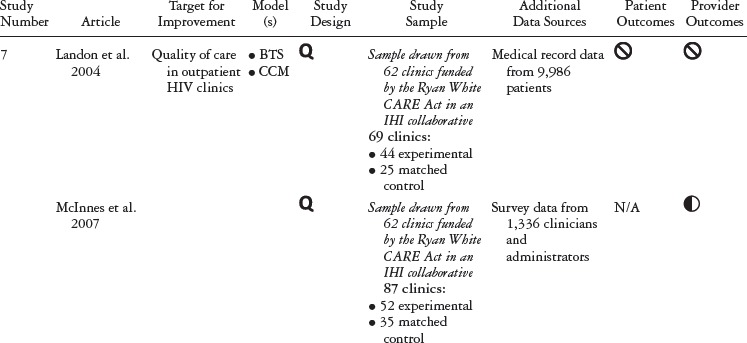

TABLE 1.

Study Details, Organized by QIC Model

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

|

Table 1 summarizes the study type, QIC model, study design, and outcomes for each study included in our review. Table 2 details the QIC components of a given study, and table 3 expands the definitions of the study characteristics and QIC components that were tracked. All the studies document the study design, QI target, the QIC model, study sample, data sources, and outcomes. We identified the QIC features discussed earlier through a review of the theoretical literature categorized into components, QI processes, and organizational involvement. QIC components refer to the QIC activities and features comprising the overarching structure of the QIC. The table's QI processes section describes how PDSAs and other QI activities were conducted, an important area of analysis because such processes are central to the model. Organizational involvement pertains to indicators of how the QIC penetrated different levels of the organization. A QI team typically is a small, multidisciplinary group, and during the collaborative, the team is expected to share the knowledge gained with the leadership and frontline staff not directly part of the collaborative. Although QI teams may not be charged explicitly with training or educating frontline staff, this can be helpful for achieving QIC improvement goals (e.g., Nembhard 2012; Nembhard and Tucker 2011).

TABLE 2.

QIC Components by Study, Organized by QIC Model

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

|

TABLE 3.

QIC Components Highlighted for Comparison

| Study Information | QIC Components | QI Processes | Organizational Involvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| This category highlights the basic study details of the published article. | To which common QIC components did the study authors explicitly refer, according to the definition of QICs compiled from a review of the literature? | Beyond the QIC's basic components, which quality improvement techniques were included? | In theory, QICs enable an organization to enact change at multiple levels within their organizational structure.Did the QIC take steps to train or otherwise involve members of the organization who were not directly included in the collaborative? |

| Target for Improvement | Length of Collaborative | Sites Collected and New Data for QI | Leadership Involvement/Outreach |

| What was the focus of the QIC? | Can a standard collaborative length be established? | During the collaborative, did sites collect new data for quality improvement purposes? | Did members of the collaborative involve or otherwise reach out to local leadership? |

| Model(s) | Pre-Work: Convened Expert Panel | Sites Reviewed Data and Used Feedback | Training for “Non-QI Team Staff Members” by Experts |

| Did the QIC align with existing collaborative models? | The BTS model calls for a planning group that identifies targets for improvement change and plans the collaborative. | Did the collaborative sites review new data and adjust their practices according to findings? | Did QIC faculty or other experts provide training for staff members who were not a part of the QI Team? |

| Study Design | Pre-Work: Organizations Required to Demonstrate Commitment | External Support with Data Synthesis and Feedback | Training for “Non-QI Team Staff Members” by the QI Team |

| Was the study quasi-experimental or a randomized control trial? | The BTS model recommends requiring formal commitments, application criteria, or “readiness” activities for QIC sites. | Did QIC faculty or other experts provide support with data synthesis and feedback? | After the collaborative, did newly trained QI team members provide training for staff members who were not a part of the QI Team? |

| Study Sample | In-Person Learning Sessions | ||

| What was the population of focus? | Teams are traditionally trained in clinical approaches and QI approaches during initial in-person sessions. | ||

| Additional Data Sources | PDSAs | ||

| Did authors examine data other than the data collected for quality improvement purposes? | Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles are a key component of the rapid cycle approach to change recommended by the BTS model. | ||

| Patient Outcomes | Multidisciplinary QI Team | ||

| Did authors report patient-level outcomes? Were the aggregate findings positive, mixed, or negative? | QICs typically involve staff members at various levels of the organization. | ||

| Provider Outcomes | QI Team Calls | ||

| Did authors report provider-level outcomes? Were the aggregate findings positive, mixed, or negative? | Calls among QI team members or members in other participating organizations are common. | ||

| Email or Web Support | |||

| Email, listservs, or other forms of web support have become a common approach for providing ongoing support. |

Update on QIC Components and Outcomes from Studies Published since 2006

Of the thirteen new articles published since Schouten and colleagues’ 2008 review, eleven were unique studies, and one (McInnes et al. 2007) was a follow-up paper to an article in the Schouten review (Landon et al. 2004). From a methodological perspective, three of the new studies were randomized controlled trials, and the remaining nine were quasi-experimental studies. Eleven articles examined provider-level outcomes, and only four contained information on patient-level outcomes. Finally, one article focused solely on the QIC's cost-effectiveness compared with the costs of usual care (Schouten et al. 2010b).

With respect to QIC structure and components, the more recent collaboratives were shorter in duration than those in Schouten and colleagues’ 2008 review, ranging from six to eighteen months, compared with one to three years, and they reported the more frequent use of email or web support. As with the collaboratives reviewed by Schouten, the majority of the recent collaboratives we studied were based on the Breakthrough Series model. Formal pre-collaborative preparation was rarely reported and was described in only five studies (Carlhed et al. 2006; Howard et al. 2007; Polacsek et al. 2009; Schouten et al. 2010a, 2010b).

With respect to outcomes, the newer studies continued to concentrate more heavily on assessing provider-level outcomes and found less evidence for QIC benefits at the patient level. In keeping with the original Schouten review, thirteen papers found significant mixed positive or positive results at the provider level. Of the four new studies examining patient-level outcomes, one found significant positive results (Barceló et al. 2010); two found mixed positive results (Carlhed et al. 2009; Schouten et al. 2010a); and one had null findings (Colón-Emeric et al. 2006).

With respect to study design, three of the more recent studies compared the QIC with another active intervention. In an RCT, Chin and colleagues (2007) compared a standard-intensity and a high-intensity QIC for diabetes care; the high-intensity condition contained a week-long train-the-trainer course for QIC members. Study outcomes did not differ across these conditions (Chin et al. 2007). Another RCT conducted by Kritchevsky and colleagues (2008) compared a standard QIC condition with a “feedback only” condition in which nonintervention sites received two customized feedback reports on five performance measures at baseline and several months later. There were no differences across the conditions, although both groups showed improvements over time on provider-level outcomes. Finally, Carlhed and colleagues (2006) conducted a quasi-experimental study in which the sites in the intervention arm were randomized to receive a standard QIC versus a model that included more web-based interaction, fewer in-person meetings, and less contact with other QI teams. No differences were found between the active conditions, and all analyses were conducted with these groups combined.

Description of QIC Components Reported in Studies

The majority of studies relied on medical chart reviews and hospital administrative data to examine outcomes. Seven studies used phone interviews or surveys with patients (Baker et al. 2005; Homer et al. 2005; Margolis et al. 2008; McInnes et al. 2007; Polacsek et al. 2009; Schouten et al. 2010a, 2010b). Sixteen studies were based on the IHI Breakthrough Series (BTS) model, and eight of them used the IHI BTS model to implement the Chronic Care model as part of a joint effort of the IHI and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF). Three more studies also used the BTS and the Chronic Care model, but not as part of the RWJF program. Two studies were based on the Vermont Oxford Network's approach, and two studies did not clearly specify the approach used.

We found fourteen crosscutting structural and process-oriented components, including in-person learning sessions, phone meetings, data reporting, feedback, training in QI methods, and use of process improvement methods. On average, each study implemented an average of six or seven QIC components. The most commonly reported components were in-person learning sessions (twenty out of twenty), PDSAs (fifteen out of twenty), multidisciplinary QI team (fourteen out of twenty), and new data collection as part of the QI process (fifteen out of twenty). However, there was very little detailed information on the ways in which the components were delivered.

Overall QIC Structure

The QICs lasted an average of twelve months (ranging from six to thirty-six months) and typically began with an in-person learning session, attended by the multidisciplinary quality improvement teams (QI teams) and led by QIC expert faculty. We followed up through additional in-person learning sessions, regular phone meetings for the QI teams, and web-based or email support. The sites conducted QI projects between QI team calls and in-person learning sessions. All in-person learning sessions and most phone meetings involved multiple sites.

Multidisciplinary Quality Improvement Teams

Fourteen of the twenty studies reported the presence of multidisciplinary quality improvement teams but did not always specify whether they represented a range of positions within the organization's hierarchy. Studies that did not report the use of a multidisciplinary team may have reported numbers of team members but did not describe the team members’ roles within the organization. All the participants may have been either direct care providers or management-level staff.

In-Person Sessions

All the studies reported having in-person learning sessions during the collaborative, typically three (ranging from one to eight). In-person sessions were typically two days long (ranging from one to three). Two studies had QICs with more frequent in-person contact. One, a QIC with eight in-person sessions, was part of an RCT comparing a standard- and high-intensity QIC (Chin et al. 2007). The second, a QIC improving pain management in nursing homes, had six bimonthly in-person meetings that were each two hours long (Baier et al. 2004).

Content of In-Person Learning Sessions

Although seventeen studies provided some information about the content of the learning sessions, the level of detail varied tremendously. All the QICs in these studies included didactic training in a particular care process or practice (e.g., the Chronic Care model, pain management guidelines). They provided training in quality improvement techniques, such as PDSA cycles. The articles contained very little detail about the structure or process of the training or which techniques were taught during the training. In eleven of the studies, the QIC purveyors had already identified areas for improvements that sites could target in QI projects (e.g., domains in the chronic care model, use of specific tools, system improvements, known implementation barriers) (Asch et al. 2005; Baker et al. 2005; Barceló et al. 2010; Benedetti et al. 2004; Carlhed et al. 2006, 2009; Chin et al. 2007; Howard et al. 2007; Landon et al. 2007; Polascek et al. 2009; Schouten et al. 2010a, 2010b). Two studies indicated that a review of the baseline data was incorporated into the collaborative, and only two studies described the training for collecting data for QI (Polacsek et al. 2009; Schouten et al. 2008).

In addition to didactic training, eight studies reported that in-person sessions were used to foster team planning and cross-site sharing of experiences. Again, the articles included few details on the structure of this collaboration. Landon and colleagues (2007) reported individual site presentations, breakout sessions, and the use of “storyboards.”

PDSAs

Fifteen studies reported using PDSAs during the learning collaboratives but offered very little information about the specific QI processes. The articles that did provide some detail typically described a “model for improvement” or PDSA cycles conducted between in-person sessions or phone calls. The studies rarely described specifically the sites’ experiences during PDSA cycles, how PDSAs were integrated into improvement efforts, or how ongoing data collection informed the QI process.

QI Team Calls

Fourteen studies reported cross-site calls for the QI teams between in-person sessions. According to those studies that reported call frequency, calls were conducted biweekly, monthly, or quarterly, with monthly the most common. No information was provided about call content or structure. Interestingly, in one study, instead of calls, the QI teams had six bimonthly, two-hour in-person meetings (Baier et al. 2004). In these meetings, the teams used “audit and feedback,” a systematic quality-improvement approach focusing on PDSA cycles, and one-on-one mentoring from nurses experienced in QI (Baier et al. 2004).

Email or Web Support

Twelve studies reported web-based or email support for the QIC participants, but they did not provide any information about the extent to which QIC participants used this support.

Quality Improvement Processes

In general, the studies provided very little information about the type of data collected, how they were used, or how they informed quality improvement activities. Fifteen studies reported some kind of ongoing data collection for the QIC (e.g., performance indicators, ongoing reporting on target outcomes). Eight studies reported that the QIC faculty gave the sites feedback, and nine studies reported external support for data synthesis and feedback.

Organizational Involvement

Nine studies reported that the organization's leadership was involved in the QIC, but it was unclear whether the organizational leadership was included on the QI team or was engaged through other means. We also examined indicators of the QIC's penetration into the broader organization by tracking any training of non-QI team members, by either QIC expert faculty or local QI team members themselves. Two studies reported training from both QIC faculty and QI team members for frontline staff members not already on the QI team. Only four other studies, however, reported that the QI team members trained additional staff in the organization.

Pre-QIC Activities

Finally, we tracked “pre-work” activities, defined as planning activities delineated by the QIC model (IHI 2003; Kilo 1998). Five studies reported that the QIC used an “expert panel,” a group that finds targets for improvement and plans the collaborative. Note that many IHI BTS collaboratives employed expert panels before launching a QIC and therefore may not have been reported. Only three studies reported requiring formal commitments, application criteria, or “readiness” activities for QIC.

Relation between QIC Components and Study Outcomes

As table 4 shows, eight studies that assessed provider outcomes reported mixed positive outcomes, and nine reported significant positive outcomes. Of the thirteen studies that examined patient-level outcomes, six reported mixed positive outcomes, and three reported significant positive outcomes. There did not appear to be a clear pattern of findings by the type of QIC model cited by the study. In addition, two studies looked at cost, with Rogowski and colleagues (2001) finding lower neonatal treatment costs for sites participating in the QIC, and Schouten and colleagues (2010b) concluding that sites that participated in the QIC demonstrated a favorable incremental cost-benefit ratio compared with those that did not. Of note, the vast majority of studies relied on administrative data or medical record abstracts to assess process of care, provider-level, and patient-level outcomes. Although some studies did include patient surveys, none directly assessed provider behavior.

TABLE 4.

Summary of Outcomes across QIC Studies

| Patient-Level | Provider-Level | |

|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Outcomes | |

| Reported Findings | (no. of studies) | (no. of studies) |

| Positive findings | 3 | 9 |

| Mixed findings | 6 | 8 |

| Null findings | 4 | 2 |

| Not applicable / Not assessed | 11 | 5 |

Given the inconsistency in reporting on the QIC components used in each collaborative and the lack of detail regarding the extent to which each component was actually used, we could not determine whether particular components of the QIC were more or less predictive of observed study outcomes. While the studies often referred to a particular QIC approach (e.g., IHI BTS, Vermont Oxford Network), most did not specify which components they used, how intensively those components were implemented, or whether the collaborative was conducted with fidelity to the original model. With the exception of a few studies (Landon et al. 2007; Polascek et al. 2009; Schouten et al. 2010a), quality improvement processes were not described in detail, and the use of data and feedback was given little space. In addition, with the exception of data on providers’ attendance at QIC activities, providers’ engagement in the QIC components was not investigated.

Discussion

QICs hold promise for increasing sustained change by building local capacity and for addressing organization- and provider-level implementation barriers that have been identified in the literature but are largely ignored by traditional consultation approaches to the intervention developer (Bero et al. 1998; Feldstein and Glasgow 2008; Nembhard 2009). QICs may also address implementation barriers by fostering local ownership of the implementation process, creating a culture of continuous learning, training organizations in QI processes that can be used to identify and target implementation barriers, promoting transparency and accountability, providing an infrastructure for addressing common barriers (provider concerns, leadership support, logistics, structural challenges), and creating an interorganizational support network from which sites can learn from others’ successes and challenges.

The number of controlled studies of QICs has grown quickly in the past several years. The majority focused on QICs for chronic medical conditions, as well as a broad range of targets (ranging from management of chronic conditions and pain to fall reduction, health disparities, neonatal intensive care, and medication-related practices in adults). In contrast, no controlled studies in behavioral health have been published, even though it is an area where QICs have begun to proliferate (e.g., Ebert et al. 2012; SAMHSA Bulletin 2012). More randomized studies are needed to test the effects of collaboratives on the process of care and provider-level and patient-level outcomes. Of the twenty studies we reviewed, only five were RCTs, and only three compared the QIC with another active condition.

Nonetheless, the studies we added to Schouten and colleagues’ 2008 work provide further evidence that QICs can effect change at the provider level, particularly the process of care variables (e.g., medication management, patient education, tracking of preventive actions). The studies comparing QICs with other active conditions appeared less likely to find differences across groups (Carlhed et al. 2006; Chin et al. 2007; Kritchevsky et al. 2008). However, we should note that each of these had its own comparator conditions, so their findings must be interpreted in context. Consistent with Schouten and colleagues’ 2008 review, the additional studies in this review reveal that patient-level variables were assessed less often and the findings were decidedly more mixed than those for provider and process of care variables. The reason may be most studies’ limited time frames, which may not have been long enough to observe any changes in patient outcomes. Our review also looked at a study on cost, finding favorable incremental cost-benefits in a collaborative on diabetes care (Schouten et al. 2010b).

Despite some studies’ positive findings for provider outcomes, it is important to note that the outcome measures were largely derived from medical records or administrative data and did not directly assess changes in provider behavior. Similarly, at the patient level, few studies directly assessed patient outcomes (e.g., Baier et al. 2004; Baker et al. 2005; Barceló et al. 2010; Benedetti et al. 2004; Carlhed et al. 2009; Horbar et al. 2001; Mangione-Smith et al. 2005; Schonlau et al. 2005; Schouten et al. 2010a). Future studies, therefore, should collect more primary data on patient- and provider-level outcomes in order to determine whether procedural improvements translate into better patient care. In addition, economic analyses and longer-term studies should look at whether improved health care outcomes, use of skills gained in the QICs (e.g., QI methods), and cost savings can be sustained over time.

A major goal of our study was to find out how QIC components are described in the empirical literature and to explore potential relations between components and outcomes. Across the studies, QICs had a similar overall structure (Horbar et al. 2001; IHI 2003; Kilo 1998; Lesar et al. 2007; Rogowski et al. 2001), but except for a few recent studies (e.g., Landon et al. 2007; Polacsek et al. 2009; Schouten et al. 2010a), not enough details about the presence or implementation of QIC components were provided. In addition, very few studies made a comparison that would allow insight into QICs’ critical features. Thus, active QIC features (i.e., having an agency director as a team member, dosage of the components, provider engagement in the QIC, interagency communication) were impossible to determine or link to specific outcomes. As QICs continue to grow in popularity, this lack of detailed information makes it impossible to replicate successful QICs, to ensure that adaptations of QICs include key active ingredients, or to determine whether negative outcomes are related to the quality and fidelity of delivering this multicomponent improvement model or differential efficacy of QICs for different EBPs.

Given the roots of the QICs in the work of management theorists such as Deming and Juran (Deming 1986; Juran 1951, 1964), the lack of specific detail about QI processes is noteworthy. Although fourteen studies reported collecting data for QI and implementing QI processes like PDSA cycles, with a few noteworthy exceptions (e.g., Landon et al. 2007; Schouten et al. 2010a), we have little specific information about how local data were used to inform QI. Because previous studies indicated that QIC participants perceive instruction in QI methods to be useful (e.g., Meredith et al. 2006; Nembhard 2009; Shortell et al. 2004), it would be helpful to have specific details about how the data were collected and used to inform QI projects and assess change. In some cases, QI projects appeared to have been undertaken based on qualitative reports and already identified QI targets, and not data (Asch et al. 2005; Horbar et al. 2001). Part of the reason may be no directly applicable data for some of the targeted practices, or no cultural shift toward the use of data and continuous quality improvement in health care. In either case, information about the key drivers of quality improvement is sorely needed.

Limitations

Limitations inherent in the systematic review process should be considered when interpreting these findings. As with any review, relevant studies may have been omitted. By searching multiple databases, reviewing the reference lists of key articles, and cross-checking with free-text search terms, we minimized the possibility of such omissions. In addition, we confined our review to studies that included control groups and may not have included all large-scale implementation models that might be similar, in some ways, to the QICs we examined. Given the few details provided by many of these controlled studies, some studies without control groups may provide additional useful information about key aspects of QICs (e.g., Dückers et al. 2009; Nembhard 2009, 2012).

Future Directions

To advance our understanding of the effectiveness of QICs, future studies need more detailed information about at least six core elements: the dosage of individual QIC components; teaching strategies and approaches to fostering cross-site collaboration; use of data to guide QI processes; fidelity to the QIC model; degree of engagement among participating sites; and sustainability of QI activities. To date, there are very few detailed, published manuals on the elements of QICs or evidence-based descriptions of the most effective ways to conduct a collaborative (e.g., Markiewicz et al. 2006). Future research also should investigate the competence and skill of the QIC faculty and the quality of implementation of QIC components. More study of QICs is needed in other aspects of health care as well, notably behavioral health, especially given the investments by federal and state entities in QICs as a vehicle to disseminate evidence-based practices. Careful study of ongoing efforts to assess QICs’ feasibility and utility for disseminating often more highly complex behavioral health interventions is much needed.

Recent studies exploring aspects of QICs that participants found useful offer helpful insights into QIC components that could be directly tested in future studies. For instance, Nembhard (2009) found six QIC features that participants in an IHI BTS model collaborative found most helpful (expert faculty, the sharing of ideas and experiences, the change package, PDSAs, interactions during in-person sessions, and the collaborative Internet). The participants found that interorganizational learning and the use of local deliberate learning activities (e.g., staff education, PDSAs) were likely to be important to outcomes (Meredith et al. 2006; Nembhard 2012; Nembhard and Tucker 2011). Other researchers have suggested that local leadership support, sites’ ability to address common implementation barriers, expert support, ongoing data collection, and the visibility of local changes achieved through QI methods may help achieve change (Ayers et al. 2005; Brandrud et al. 2011; Dückers et al. 2009; Pinto et al 2011). A related focus for future research is the development of methods that can be used to understand QICs’ features and the results of studies in various contexts and intervention targets. For example, measures like the one developed by Schouten, Grol, and Hulscher (2010) that assess QICs’ core features could be fielded and refined. Similarly, measures that assess an organization's implementation progress and process, such as the Stages of Implementation Completion, could be further studied (Chamberlain, Brown, and Saldana 2011). Recent research also has highlighted the importance of documenting and reporting sufficient detail about the study context in RCTs of complex interventions (Wells et al. 2012). Such information is critical to understanding the transferability of complex interventions as well as issues related to internal and external validity (Wells et al. 2012).

Once the active ingredients of QICs are identified, health care researchers will be able to develop and test theories of change. Using a social-ecological framework, QIC and similar interventions will probably be able to operate at multiple levels in the system (i.e., intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, community, and macropolicy) (Weiner et al. 2012). QIC participants have noted, for example, that at the intrapersonal and interpersonal levels, QICs provide skills, motivation, and social support (Nembhard 2009). These findings are consistent with research suggesting the importance of social networks to large-scale, multisite implementation efforts (Palinkas et al. 2011). Organizationally, QICs could lead to better data infrastructure and less service fragmentation. Causal modeling strategies that account for the complementary and synergistic effects in multilevel interventions would help move the field forward (Weiner et al. 2012).

In summary, the empirical literature on QICs has grown in recent years and shows promise for improving some aspects of clinical care, particularly those related to quality indicators and provider variables. Given the widespread use of QICs as an implementation strategy, however, the existing research literature provides only limited support for the overall effectiveness of QICs in improving patient outcomes and provides little insight into which QIC attributes are most likely to produce the desired change. To maximize the effectiveness and practical relevance of these models as a change strategy, understanding the specific features that drive change is a necessary next step.

Acknowledgments

Writing of the article was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, P30 MH090322 (Hoagwood), and K01MH083694 (Nadeem).

References

- Asch SM, Baker DW, Keesey JW, Broder M, Schonlau M, Rosen M, Wallace PL, Keeler EB. Does the Collaborative Model Improve Care for Chronic Heart Failure? Medical Care. 2005;43(7):667–75. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000167182.72251.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers LR, Beyea SC, Godfrey MM, Harper DC, Nelson EC, Batalden PB. Quality Improvement Learning Collaboratives. Quality Management in Healthcare. 2005;14(4):234–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baier RR, Gifford DR, Patry G, Banks SM, Rochon T, DeSilva D, Teno JM. Ameliorating Pain in Nursing Homes: A Collaborative Quality-Improvement Project. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(12):1988–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52553.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DW, Asch SM, Keesey JW, Brown JA, Chan KS, Joyce G, Keeler EB. Differences in Education, Knowledge, Self-Management Activities, and Health Outcomes for Patients with Heart Failure Cared for under the Chronic Disease Model: The Improving Chronic Illness Care Evaluation. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2005;11(6):405–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.03.010. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R. Collaborating for Improvement: The Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Breakthrough Series. New Medicine. 1997;1:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Barceló A, Cafiero E, Mesa M, de Boer AE, Lopez MG, Jiménez RA, Esqueda AL, Martinez JA, Holguin EM, Meiners M, Bonfil GM, Ramirez SN, Flores EP, Robles S. Using Collaborative Learning to Improve Diabetes Care and Outcomes: The VIDA Project. Primary Care Diabetes. 2010;4(3):145–53. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2010.04.005. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DR, Drake RE, Bond GR. Benchmark Outcomes in Supported Employment. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2011;14(3):230–36. doi: 10.1080/15487768.2011.598083. [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti R, Flock B, Pedersen S, Ahern M. Improved Clinical Outcomes for Fee-for-Service Physician Practices Participating in a Diabetes Care Collaborative. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Safety. 2004;30(4):187–94. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(04)30020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thomson MA. Closing the Gap between Research and Practice: An Overview of Systematic Reviews of Interventions to Promote the Implementation of Research Findings. BMJ. 1998;317(7156):465–68. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick DM. Continuous Improvement as an Ideal in Health Care. New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;320(1):53–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901053200110. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901053200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick DM. Quality Comes Home. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1996;125(10):839–43. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-10-199611150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Drake RE, Rapp C, McHugo G, Xie H. Individualization and Quality Improvement: Two New Scales to Complement Measurement of Program Fidelity. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2009;36(5):349–57. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0226-y. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0226-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandrud AS, Schreiner A, Hjortdahl P, Helljesen GS, Nyen B, Nelson EC. Three Success Factors for Continual Improvement in Healthcare: An Analysis of the Reports of Improvement Team Members. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2011;20(3):251–59. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.038604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundy P. Using Drama in the Counselling Process: The “Moving on” Project. Research in Drama Education. 2006;11(1):7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Carlhed R, Bojestig M, Peterson A, Åberg C, Garmo H, Lindahl B. Improved Clinical Outcome after Acute Myocardial Infarction in Hospitals Participating in a Swedish Quality Improvement Initiative. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2009;2(5):458–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.842146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlhed R, Bojestig M, Wallentin L, Lindström G, Peterson A, Åberg C, Lindahl B. Improved Adherence to Swedish National Guidelines for Acute Myocardial Infarction: The Quality Improvement in Coronary Care (QICC) Study. American Heart Journal. 2006;152(6):1175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Brown CH, Saldana L. Observational Measure of Implementation Progress in Community Based Settings: The Stages of Implementation Completion (SIC) Implementation Science. 2011;6(1):116. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin MH, Drum ML, Guillen M, Rimington A, Levie JR, Kirchhoff AC, Quinn M, Schaefer CT. Improving and Sustaining Diabetes Care in Community Health Centers with the Health Disparities Collaboratives. Medical Care. 2007;45(12):1135–43. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31812da80e. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31812da80e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colón-Emeric C, Schenck A, Gorospe J, McArdle J, Dobson L, DePorter C, McConnell E. Translating Evidence-Based Falls Prevention into Clinical Practice in Nursing Facilities: Results and Lessons from a Quality Improvement Collaborative. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54(9):1414–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00853.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cretin S, Shortell SM, Keeler EB. An Evaluation of Collaborative Interventions to Improve Chronic Illness Care. Evaluation Review. 2004;28(1):28–51. doi: 10.1177/0193841X03256298. doi: 10.1177/0193841×03256298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deming WE. Out of the Crisis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Dückers ML, Spreeuwenberg P, Wagner C, Groenewegen PP. Exploring the Black Box of Quality Improvement Collaboratives: Modelling Relations between Conditions, Applied Changes and Outcomes. Implementation Science. 2009;4(1):74. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert L, Amaya-Jackson L, Markiewicz J, Kisiel C, Fairbank J. Use of the Breakthrough Series Collaborative to Support Broad and Sustained Use of Evidence-Based Trauma Treatment for Children in Community Practice Settings. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012;39(3):187–99. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0347-y. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0347-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM) Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2008;34(4):228–43. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homer CJ, Forbes P, Horvitz L, Peterson LE, Wypij D, Heinrich P. Impact of a Quality Improvement Program on Care and Outcomes for Children with Asthma. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159(5):464–69. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.464. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horbar JD, Carpenter JH, Buzas J, Soll RF, Suresh G, Bracken MB, Leiton LC, Plsek PE, Sinclair JC. Collaborative Quality Improvement to Promote Evidence Based Surfactant for Preterm Infants: A Cluster Randomised Trial. BMJ. 2004;329(7473):1004. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7473.1004. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7473.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horbar JD, Rogowski J, Plsek PE, Delmore P, Edwards WH, Hocker J, Kantak AD, Lewallen P, Lewis W, Lewit E, McCarroll CJ, Mujsce D, Payne NR, Shiono P, Soll RF, Leahy K, Carpenter JH. Collaborative Quality Improvement for Neonatal Intensive Care. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):14–22. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.14. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DH, Siminoff LA, McBride V, Lin M. Does Quality Improvement Work? Evaluation of the Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaborative. Health Services Research. 2007;42(6, part 1):2160–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IHI (Institute for Healthcare Improvement) The Breakthrough Series: IHI's Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement. Boston: 2003. IHI Innovation Series white paper. [Google Scholar]

- IOM (Institute of Medicine), Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa K. What Is Total Quality Control? The Japanese Way. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Juran JM. Quality Control Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Juran JM. Managerial Breakthrough. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Kilo CM. A Framework for Collaborative Improvement: Lessons from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Breakthrough Series. Quality Management in Health Care. 1998;6(4):1–14. doi: 10.1097/00019514-199806040-00001. Summer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritchevsky SB, Braun BI, Bush AJ, Bozikis MR, Kusek L, Burke JP, Wong ES, Jernigan J, Davis CC, Simmons B. The Effect of a Quality Improvement Collaborative to Improve Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Surgical Patients. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;149(7):W472–93. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-7-200810070-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffel G, Blumenthal D. The Case for Using Industrial Quality Management Science in Health Care Organizations. JAMA. 1989;262(20):2869–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03430200113036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landon BE, Hicks LRS, O'Malley AJ, Lieu TA, Keegan T, McNeil BJ, Guadagnoli E. Improving the Management of Chronic Disease at Community Health Centers. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356(9):921–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa062860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landon BE, Wilson IB, McInnes K, Landrum MB, Hirschhorn L, Marsden PV, Gustafson D, Cleary PD. Effects of a Quality Improvement Collaborative on the Outcome of Care of Patients with HIV Infection: The EQHIV Study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;140(11):887–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesar TS, Anderson ER, Fields J, Saine D, Gregoire J, Fraser S, Parkin M, Mattis A. The VHA New England Medication Error Prevention Initiative as a Model for Long-Term Improvement Collaboratives. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2007;33(2):73–82. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangione-Smith R, Schonlau M, Chan KS, Keesey J, Rosen M, Louis TA, Keeler E. Measuring the Effectiveness of a Collaborative for Quality Improvement in Pediatric Asthma Care: Does Implementing the Chronic Care Model Improve Processes and Outcomes of Care? Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2005;5(2):75–82. doi: 10.1367/A04-106R.1. doi: 10.1367/a04-106r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis PA, McLearn KT, Earls MF, Duncan P, Rexroad A, Reuland CP, Fuller S, Paul K, Neelon B, Bristol TE, Schoettker PJ. Assisting Primary Care Practices in Using Office Systems to Promote Early Childhood Development. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2008;8(6):383–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markiewicz J, Ebert L, Ling D, Amaya-Jackson L, Kisiel C. Learning Collaborative Toolkit. Los Angeles: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes DK, Landon BE, Wilson IB, Hirschhorn LR, Marsden PV, Malitz F, Barini-Garcia M, Cleary PD. The Impact of a Quality Improvement Program on Systems, Processes, and Structures in Medical Clinics. Medical Care. 2007;45(5):463–71. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000256965.94471.c2. doi:410.1097/1001.mlr.0000256965.0000294471.c0000256962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith LS, Mendel P, Pearson M, Wu S-Y, Joyce G, Straus JB, Ryan G, Keeler E, Unutzer J. Implementation and Maintenance of Quality Improvement for Treating Depression in Primary Care. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(1):48–55. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittman BS. Creating the Evidence Base for Quality Improvement Collaboratives. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;140(11):897–901. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nembhard IM. Learning and Improving in Quality Improvement Collaboratives: Which Collaborative Features Do Participants Value Most? Health Services Research. 2009;44(2, part 1):359–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00923.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nembhard IM. All Teach, All Learn, All Improve? The Role of Interorganizational Learning in Quality Improvement Collaboratives. Health Care Management Review. 2012;37(2):154–64. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e31822af831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nembhard IM, Tucker AL. Deliberate Learning to Improve Performance in Dynamic Service Settings: Evidence from Hospital Intensive Care Units. Organization Science. 2011;22(4):907–22. [Google Scholar]

- Øvretveit J, Bate P, Cleary P, Cretin S, Gustafson D, McInnes K, McLeod H, Molfenter T, Plsek P, Robert G, Shortell S, Wilson T. Quality Collaboratives: Lessons from Research. Quality & Safety in Health Care. 2002;11(4):345–51. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.4.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Holloway IW, Rice E, Fuentes D, Wu Q, Chamberlain P. Social Networks and Implementation of Evidence-Based Practices in Public Youth-Serving Systems: A Mixed-Methods Study. Implementation Science. 2011;6:113. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A, Benn J, Burnett S, Parand A, Vincent C. Predictors of the Perceived Impact of a Patient Safety Collaborative: An Exploratory Study. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2011;23(2):173–81. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzq089. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzq089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plsek PE. Collaborating across Organizational Boundaries to Improve the Quality of Care. American Journal of Infection Control. 1997;25(2):85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0196-6553(97)90033-x. doi: 10.1016/s0196-6553(97)90033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polacsek M, Orr J, Letourneau L, Rogers V, Holmberg R, O'Rourke K, Hannon C, Lombard KA, Gortmaker SL. Impact of a Primary Care Intervention on Physician Practice and Patient and Family Behavior: Keep ME Healthy—The Maine Youth Overweight Collaborative. Pediatrics. 2009;123(suppl. 5):S258–66. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2780C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogowski JA, Horbar JD, Plsek PE, Baker LS, Deterding J, Edwards WH, Hocker J, Kantak AD, Lewallen P, Lewis W, Lewit E, McCarroll CJ, Mujsce D, Payne NR, Shiono P, Soll RF, Leahy K. Economic Implications of Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Collaborative Quality Improvement. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):23–29. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.23. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA Bulletin. SAMHSA Is Accepting Applications for up to $30 Million in State Adolescent Enhancement and Dissemination Grants. 2012. Available at http://www.samhsa.gov/newsroom/advisories/1206124742.aspx (accessed June 12, 2012)

- Schoenwald S, Hoagwood KE. Effectiveness, Transportability, and Dissemination of Interventions: What Matters When? Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(9):1190–97. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1190. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Sheidow AJ, Letourneau EJ. Toward Effective Quality Assurance in Evidence-Based Practice: Links between Expert Consultation, Therapist Fidelity, and Child Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(1):94–104. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_10. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3301_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonlau M, Mangione-Smith R, Chan KS, Keesey J, Rosen M, Louis TA, Wu S, Keeler E. Evaluation of a Quality Improvement Collaborative in Asthma Care: Does It Improve Processes and Outcomes of Care? Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(3):200–208. doi: 10.1370/afm.269. doi: 10.1370/afm.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten LM, Grol RP, Hulscher ME. Factors Influencing Success in Quality-Improvement Collaboratives: Development and Psychometric Testing of an Instrument. Implementation Science. 2010;5(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten LMT, Hulscher MEJL, Huijsman JJE, van Everdingen R, Grol RPTM. Evidence for the Impact of Quality Improvement Collaboratives: Systematic Review. BMJ. 2008;336(7659):1491–94. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39570.749884.BE. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39570.749884.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten LMT, Hulscher MEJL, Huijsman JJE, van Everdingen R, Niessen LW, Grol R. Short- and Long-Term Effects of a Quality Improvement Collaborative on Diabetes Management. Implementation Science. 2010a;5(1):1491–94. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten LMT, Niessen LW, Grol JWAM, van de Pas RPTM, Hulscher MEJL. Cost-Effectiveness of a Quality Improvement Collaborative Focusing on Patients with Diabetes. Medical Care. 2010b;48(10):884–91. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181eb318f. doi:810.1097/MLR.1090b1013e3181eb1318f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer TJ, Wagner D, Chessare J, Schall MW, McBride V, Zampiello FA, Perdue J, O'Connor K, Lin MJ-Y, Burdick J. US Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaborative Increases Organ Donation. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly. 2008;31(3):190–210. doi: 10.1097/01.CNQ.0000325044.78904.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortell SM, Marsteller JA, Lin M, Pearson ML, Wu S-Y, Mendel P, Cretin S, Rosen M. The Role of Perceived Team Effectiveness in Improving Chronic Illness Care. Medical Care. 2004;42(11):1040–48. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200411000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg LI. If You've Seen One Quality Improvement Collaborative. Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(3):198–99. doi: 10.1370/afm.304. doi: 10.1370/afm.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner BJ, Lewis MA, Clauser SB, Stitzenberg KB. In Search of Synergy: Strategies for Combining Interventions at Multiple Levels. JNCI Monographs. 2012;2012(44):34–41. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs001. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells M, Williams B, Treweek S, Coyle J, Taylor J. Intervention Description Is Not Enough: Evidence from an In-Depth Multiple Case Study on the Untold Role and Impact of Context in Randomised Controlled Trials of Seven Complex Interventions. Trials. 2012;13(1):95–111. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T, Berwick DM, Cleary P. What Do Collaborative Improvement Projects Do? Experience from Seven Countries. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2004;30(suppl. 1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(03)29011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young PC, Glade GB, Stoddard GJ, Norlin C. Evaluation of a Learning Collaborative to Improve the Delivery of Preventive Services by Pediatric Practices. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1469–76. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2210. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]