Abstract

Advancement of materials technology has been immense, especially in the past 30 years. Ceramics has not been new to dentistry. Porcelain crowns, silica fillers in composite resins, and glass ionomer cements have already been proved to be successful. Materials used in the replacement of tissues have come a long way from being inert, to compatible, and now regenerative. When hydroxyapatite was believed to be the best biocompatible replacement material, Larry Hench developed a material using silica (glass) as the host material, incorporated with calcium and phosphorous to fuse broken bones. This material mimics bone material and stimulates the regrowth of new bone material. Thus, due to its biocompatibility and osteogenic capacity it came to be known as “bioactive glass-bioglass.” It is now encompassed, along with synthetic hydroxyapatite, in the field of biomaterials science known as “bioactive ceramics.” The aim of this article is to give a bird's-eye view, of the various uses in dentistry, of this novel, miracle material which can bond, induce osteogenesis, and also regenerate bone.

Keywords: Biocompatible, bioinert, bioregenerative, hydroxyapatite, osteogenic

INTRODUCTION

A glimpse through the history of development of materials used in dentistry, specifically replacement materials, shows that the aim has been to create materials that were as chemically inert as possible. In mid 60s, the biocompatibility and long-term survival of the material was achieved by minimizing the material-host interaction. As the materials used at that time were mostly metallic, this led to corrosion and eventual failure caused by the aggressive nature of body fluids. This led to the search of materials that could withstand the chemical attack of the body.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the search for better biocompatibility of implant materials resulted in the new concept of bioceramic materials that would mimic natural bone tissue. Hydroxyapatite, a naturally occurring ceramic mineral, was also the mineral component of bone. Thus, only synthetic hydroxyapatite was believed to be entirely compatible with the body.

During this period, Professor Hench came up with a new biocompatible material using silica (glass) as a base material that could be mixed with other ingredients such as calcium to unite fractured bones. This mimics normal bone and stimulates the regrowth of new bone between the fractures.[1,2] By using this material, the trend of implant materials was shifted to stimulate body's own regenerative capabilities. This new glass material on dissolving, in normal physiological environment, activates genes controlling osteogenesis and growth factor production[2,3,4] (within 48 hours) with bone produced of equivalent quality to natural bone.[3,5] The trabecular bone growth and quantity were much more than produced by synthetic hydroxyapatite.[6,7] After implantation of this material in bone tissue, these glass materials resisted removal from the implant site -- which was coined as “bonded to bone” by Hench.[8,9] Hench used the term “bioactive glass” to describe this attachment.[1,10,11] A bioactive material is defined as a material that elicits a specific biological response at the interface of the material, which results in the formation of a bond between the tissue and that material.[12,13] The term bioactive was later applied to encompass the entire field of biomaterials science known as bioactive ceramics.[14] The gene activation, bone regenerative capability with better quality and quantity of bone equivalent to normal bone, and high level of bioactivity are unique only to bioglass when compared with synthetic hydroxyapatite and any other allograft, which more than justifies the use of bioglass.

The other advantages of bioglass over synthetic hydroxyapatite are the biological fixation, and the capability of bonding to both hard and soft tissues, whereas hydroxyapatite binds only to hard tissues and also needs an exogenous covering to hold the implants in place.[15]

Composition and Mechanism of Activity

The original bioglass (45S5) composition is as follows: 45% silica (SiO2), 24.5% calcium oxide (CaO), 24.5%sodium oxide (Na2O), and 6% phosphorous pentoxide (P2O5) in weight percentage. Bioglass material is composed of minerals that occur naturally in the body (SiO2, Ca, Na2O, H, and P), and the molecular proportions of the calcium and phosphorous oxides are similar to those in the bones. The surface of a bioglass implant, when subjected to an aqueous solution, or body fluids, converts to a silica-CaO/P2O5-rich gel layer that subsequently mineralizes into hydroxycarbonate in a matter of hours.[16,17,18] More the dissolution, better the bone tissue growth.[7] This gel layer resembles hydroxyapatite matrix so much that osteoblasts were differentiated and new bone was deposited.[14]

Ca5(PO4)3(OH) is the chemical formula for hydroxyapatite, a natural mineral form of calcium apatite and usually written as Ca10(PO)6(OH)2.

The bioactivity level of any material is measured by bioactivity Index (IB). Bioactivity Index of a material is the time taken for more than half of the interface to bond, i.e., t0.5bb.

IB = 100/t0.5bb

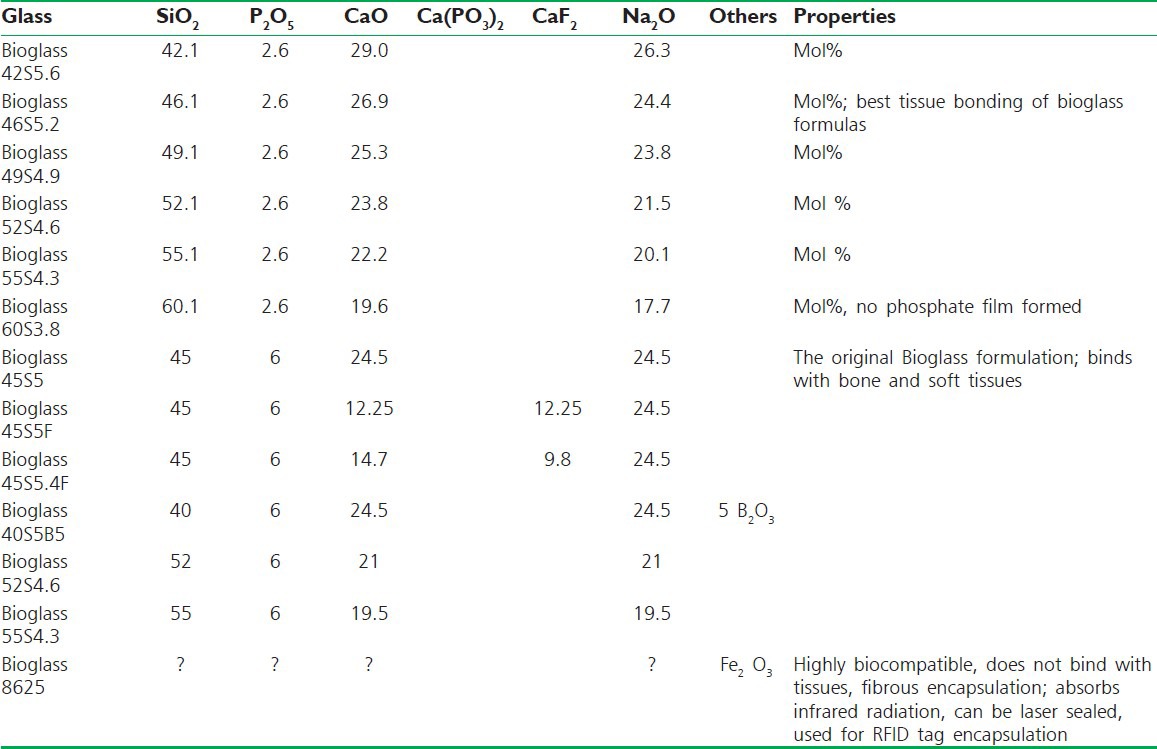

Any material with the value of IB greater than 8, like 45S5, will bond to both soft and hard tissues. Materials such as synthetic hydroxyapatite with IB value < 8 but > 0 will bind only to hard tissue.[19] The typical composition of the bioglass and bioceramics is indicated in Table 1.[20,21]

Table 1.

Composition of bioglass and glass ceramics

When the proportions of these minerals are altered, the properties of the bioglass change, which can be suited to be used in various body parts accordingly.

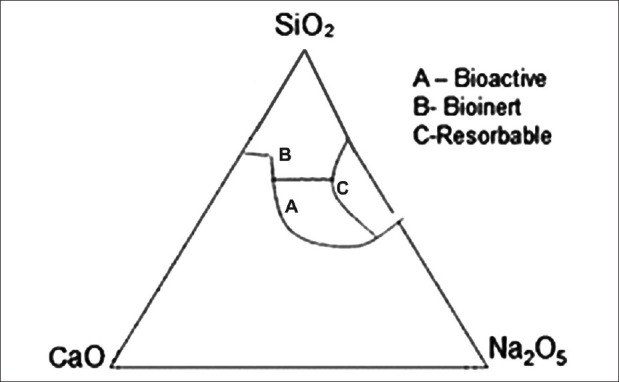

As depicted in the triangle [Figure 1], varying proportions of the components cause the bioglass to be bioinert, bioresorbable, or bioregenerative.[22]

Figure 1.

Property changes of bioglass materials

Bioglass is available in multiple forms: Particulate, pellets, powder, mesh, and cones. Interestingly it can be moulded into any desired form [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Forms of bioglass as materials

BIOGLASS AS GRAFT MATERIAL

Materials chosen for grafting need to be biocompatible, bioresorbable, and osteogenic. Treatment for the elimination of osseous defects due to periodontal diseases, pathologies, and surgeries include autogenous bone grafts, alloplast, guided tissue regeneration, combination of guided tissue regeneration and decalcified freeze dried bone.

Limitations of autogenous bone grafts are additional surgical trauma and not enough tissue material to fill the defect. To overcome these restrictions, alloplastic materials were used. But again adverse immune response and disease transmission have restricted its widespread acceptance. The membrane exposure and the local infection that follows in guided tissue regeneration obstruct bone formation.

The last three decades saw the trials of many glass and glass-ceramic compositions. The glass-silicate composition developed by Hench showed bonding to bone. The bioactive glass has been observed to bond with certain connective tissue through collagen formation with the glass surface.[22] Bioactive glass with its interconnected porosity has added advantages in hard-tissue prosthesis. The porous structure supports tissue in/on growth and improves implant stability by biologic fixation. But its low fracture resistance makes it more useful in load-free areas.

Trials have been conducted to compare repair response of bioactive glass synthetic bone graft particles and open debridement in treatment of human periodontal osseous defects. Fifty-nine defects in 16 healthy adults were chosen. Clinical parameters of probing depths, clinical attachment levels, and gingival recession were recorded. Radiographs and soft tissue presurgical measurements were repeated at 6, 9, and 12 months. There was significantly less gingival recession in bioactive sites compared with control sites. More defect fill in bioactive glass sites. Bioactive glass sites showed significant improvement in clinical parameters compared with open flap debridement.[23]

Bioglass was used in particle form to fill periodontal osseous defects.[22,23,24,25] Bone was seen to be surrounding individual particles from many sites.[26] Twenty patients age 23--55 years (44 sites) with intrabony defects completed the 1-year study. Follow-up was carried out weekly, at 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 1 year post surgery. Results showed a significant increase in radiographic density and volume between the defects treated with bioactive glass when compared with those treated with surgical debridement only. Thus, bioactive glass was found to be effective in the treatment of intrabony defects.[27]

Another study[28] was conducted with bioglass particulates in periodontal osseous defects of 12 patients. Data was collected initially and at 3, 6, 24 months post-treatment intervals. Considerable improvements of all clinical parameters of mean probing depth reduction, mean attachment gain, and mean radiographic bone fill were noted. Follow-up of over 24 months showed stable results. The material elicited extraordinary tissue response and hassle-free handling.

BIOGLASS AS ENDOSSEOUS IMPLANT

After dental extraction, resorption of alveolar bone affects majority of patients.[29,30,31] This resorption leads to ill-fitting dentures resulting in compromised masticatory efficiency, oral and systemic health problems, and esthetics. Alveolar bone height is maintained on stimulation by the periodontal membrane and teeth or roots being present.[32,33] After extraction, stimulation is lost to the alveolar bone and the pressure from dentures cause bone resorption.[34,35] The resorption rate varies with from individual to individual and at varying levels in the same individual.[32,33,36]

Many treatment modalities have been suggested for augmentation of the atrophic ridge.[37] Although autogenous bone grafting can be a recommended treatment modality and also with reduced antigenicity of freeze dried bone rejection, infections and transmission of disease limit its usage.

Ankylosis, resorption, and pocket formation make replantation of natural roots a failure. Thus, maintaining the residual alveolar ridge is better than trying to augment it. While many materials such as carbon, calcium phosphate ceramics, tricalcium phosphate, hydroxyapatite, coraline hydroxyapatite, and bioglass have been used in augmentation of alveolar ridge, dehiscence of these materials, mostly within 12 months, made implantation difficult.

Considering these obstacles, bioglass was the most promising implant material, as proved by the study carried out by Stanley et al., using cone-shaped bioglass[38,39] The study was done on baboons for 2 years. Bioglass implants were placed in the extracted sockets of incisors, splinted to adjacent natural teeth for 3 months and then desplinted for another 3 months. Bioglass caused ankylosis, usually by direct deposition of bone on the implant surface,[40] with the added advantage of gradation of mineralization within the bioglass gel layer reducing from outward to inward providing mechanical compliance like the periodontal membrane in the natural tooth.

Another study[30,41,42] had 242 cone implants placed in 29 patients. The patients were observed from 12 to 32 months. The implants were found to be surrounded with new bone on postoperative evaluation of surgical exposure. Dehiscence was not encountered even at 12 months, compared with dehiscence at 10 months with other materials. Infectionless normal tissue healing with new bone formation as sighted in radiographs made bioglass a highly biocompatible innovation.

BIOGLASS AS REMINERALIZING AGENT

Around 35% of patients complain of dentinal hypersensitivity. Initial treatment was by calcium phosphate precipitation method using dentin etching. The characteristic osteogenic activity of bioactive and biocompatible glass made it worth its trial in occluding dentinal tubules. A new dentifrice formulation[43] containing a modified bioglass material, replacing a part of the abrasive silica component, was compared with original 45S6 bioactive glass. The results evidenced that original bioglass dislodged easily when compared with modified bioglass, proving that bioglass, when used with a suitable vehicle, can be an excellent treatment for dentine sensitivity.

A second study[44] compared mineralization of bioactive glass S53P4 with regular commercial glass. The bioactive glass released more silica than commercial glass along with lesser decalcification during the process when pretreated with bioactive glass. Thus, bioactive glass S53P4 is more efficient in treatment of dentinal hypersensitivity.

In support to the above study, Salonen et al.,[45] proved that S53P4 induced tissue mineralization at the glass-tissue interface and elsewhere. The study widened the use of bioglass in treatment of caries prophylaxis, in dentinal hypersensitivity, as root apex sealer, and as metal implant coating.

Among the uses of bioactive glass, the efficacy of sol-gel bioglass particles, and melt-driven bioglass particles were tested and compared.[46] Dentine treated with melt-driven bioglass showed an apatite layer, which was continuous, adherent, and with particle formation. Bioerodible gel films have also been proved to be useful in the delivery of remineralizing agents.[47]

BIOGLASS AS ANTIBACTERIAL AGENT

The reactions of bioglass in aqueous environment, leading to osseointegration prompted scientists to check its antibacterial activity.[48] Streptococcus sanguis, Streptococcus mutans, and Actinomyces viscosus were suspended in nutrient broth and artificial saliva or Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium plus 10% fetal calf serum with or without particulate bioglass. There was considerable reduction in the viability of all bacteria tested, in both media, when compared with inert glass controls. In conclusion, the antibacterial effect of bioglass was attributed to its alkaline nature.[49]

BIOGLASS IN DRUG DELIVERY

The basic criteria for selection of any drug delivery system should be that it is inert; biologically compatible; has good mechanical strength; is good from the aspect of patient comfort; has the ability to carry high doses of the drug, with no risk of accidental release; and is in easy administering, removal, fabrication, and sterilization. There are three basic mechanisms through which active agents can be delivered: By diffusion, activation of solvent or swelling, and degradation.

Controlled drug delivery means preplanned delivery of a drug. The aim was to be more effective without possibilities of increased or decreased dosages, and also greater patient acceptance, maximal usage of the drug, with least administrations.

The importance is moresoeverwhen this accuracy is limited while using conventional drugs or injections. For example, when water soluble drugs should be slowly released, low soluble drugs should be released fast, specific-site delivery, nanoparticulate drug delivery systems, and where carriers should be quickly removed. Studies have proved that bioglass in such casescan be a successful carrier in drug delivery.

A study used Fick's diffusion law to treat osteomyelitis with teicoplanin.[50] Teicoplanin was the liquid and borate bioactive glass the solid carrier along with chitosan, citric acid, and glucose. The results of the study showed bioactivity of hydroxyapatite forming from the bioglass when the drug was being released. This system cured the osteomyelitis in tibial bone of rabbits in vivo, and also promoted formation of the tibial bone.

Bioglass has been tried as a vehicle for drug delivery. Vancomycin on bioglass carrier has been tested for treating osteomyelitis with success.[51]

Indomethacin was tried with self-setting bioactive cement based on CaO-SiO2 -P2O5 glass. This mixture hardened and formed hydroxyapatite in about 5 minutes with volume shrinkage of 5% in simulated body fluid.[52]

The fast-acting anti-inflammatory drug ibuprofen was released in the first 8 hours when immersed in simulated body fluid.[53,54]

BIOGLASS IN BONE TISSUE ENGINEERING

One of the biggest hurdles in tissue engineering was to mimic the extracellular matrix. Scaffolds built using biocomposite nanofibers and nanohydroxyapatite were naturally very porous, which in turn facilitated good cell occupancy, vascularity, movement of nutrients, and metabolic waste products. Studies comparing bioinert with bioactive glass ceramic templates, produced increased osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. This system helped the human fetal osteoblasts to adhere, migrate, proliferate, and mineralize into bone, which was a tremendous step ahead in the bone defect filling.[3,55]

CONCLUSION

On critical analysis, Young's modulus of bioglass being between 30 and 50 GPa, nearly that of natural bone, is a great advantage.[20] Maybe a small disadvantage is the low mechanical strength and decreased fracture resistance. This can be easily overcome by altering the composition, using it in low load-bearing areas, and using it for the bioactive stage. Very clearly, the disadvantages of bioglass are minimal compared with its versatile strength and huge foray of uses.

The replacement of tissues demands very high importance in this technological era. As highlighted in the present article, bioglass is a versatile replacement material, as it is available in multiple forms and also can be moulded into desired forms as per the need of the user. Thus, its scope for use also increases manifold. After two decades of being in use, the most telling is that bioglass has not reported any adverse responses when used in the body. As the use of these compositions increases, in varying clinical fields, it will bring into sight, better applications in repair as well as regeneration of natural tissues.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hench LL, West JK. Biological applications of bioactive glasses. Life Chem Reports. 1996;13:187–241. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hench LL, Xynos ID, Buttery LD, Polak JM. Bioactive materials to control cell cycle. Mater Res Innovations. 2000;3:313–23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xynos ID, Hukkanen MV, Batten JJ, Buttery LD, Hench LL, Polak JM. Bioglass 45S5® stimulates osteoblast turnover and enhances bone formation in vitro: Implications and applications for bone tissue engineering. Calcif Tissue Int. 2000;67:321–9. doi: 10.1007/s002230001134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xynos ID, Edgar AJ, Buttery LD, Hench LL, Polak JM. Ionic products of bioactive glass dissolution increase proliferation of human osteoblasts and induce insulin-like growth factor II mRNA expression and protein synthesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:461–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Details of the clinical cases are available from US Biomaterials Inc., Alachua, FL, USA, 32615 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hench LL, Jones JR, Sepulveda P. Chapter 1. Future Strategies for Tissue and Organ Replacement. Imperial College Press; Bioactive materials for tissue engineering scaffolds. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ducheyne P, Qui Q. Bioactive ceramics: The effect of surface reactivity on bone formation and bone cell function. Biomaterials. 1999;20:2287–303. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hench LL, Splinter RJ, Allen WC, Greenlee TK. Bonding mechanisms at the interface of ceramic prosthetic materials. J Biomed Mater Res. 1972;2:117–41. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hench LL, Paschall HA. Histochemical responses at a materials interface. J Biomed Mater Res. 1974;5:49–54. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820080307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hench LL, Wilson J. Singapore: World Scientific; 1993. Introduction to Bioceramics. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao W, Hench LL. Bioactive materials. Ceram Int. 1996;22:493–507. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ratner BD, Hoffman AS, Schoen FJ, Lemmons JE, editors. An Introduction to Materials in Medicine. Biomaterials Science. 1996:484. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hench LL. Biomaterials: A forecast for the future. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1419–23. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Developments in Biocompatible Glass Compositions. Medical Device and Diagnostic Industry Magazine MDDI Article Index. An MD and DI, Column Special Section, 1999 Mar [Google Scholar]

- 15.Padrines M, Rohanizadeh R, Damiens C, Heymann D, Fortun Y. Inhibition of apatite formation by vitronectin. Connect Tissue Res. 2000;41:101–8. doi: 10.3109/03008200009067662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersson OH, Karlsson KH, Kangasniemi K. Calcium phosphate formation at the surface of bioactive glasses in vivo. J Non-Cryst Solids. 1990;119:290–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hench LL, Wilson J. Surface-active biomaterials. Science. 1984;226:630–6. doi: 10.1126/science.6093253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallace KE, Hill RG, Pembroke JT, Brown CJ, Hatton PV. Influence of sodium oxide content on bioactive glass properties. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 1999;10:697–701. doi: 10.1023/a:1008910718446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hench LL. Bioceramics: From concept to clinic. J Am Ceram Soc. 1991;74:1487–510. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donglu Shi. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2004. Biomaterials and Tissue Engineering; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bronzino JD. Vol. 1. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2000. Biomedical Engineering Handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elsberg LL, Lobel KD, Hench LL. Geometric effects on the reaction stages of bioactive glasses. (Unpublished) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Froum SJ, Weinberg MA, Tarnow D. Comparison of bioactive glass synthetic bone graft particles and open debridement in the treatment of human periodontal defects. A clinical study. J Periodontol. 1998;69:698–709. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.6.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson J, Low SB. Bioactive ceramics for periodontal treatment: Comparative studies in the Patus monkey. J Appl Biomater. 1992;3:123–9. doi: 10.1002/jab.770030208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson J, Low S, Fetner A, Hench LL. Bioactive materials for periodontal treatment: A comparative study. In: Pizzoferrato A, Marchetti PG, Ravaglioli A, Lee AJ, editors. Biomaterials and Clinical Applications. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1987. pp. 223–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oonishi H, Hench LL, Wilson J, Sugihara F, Tsuji E, Kushitani S, et al. Comparative bone growth behaviour in granules of bioceramic materials of various sizes. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;44:31–43. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199901)44:1<31::aid-jbm4>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zamet JS, Darbar UR, Griffiths GS, Bulman JS, Brägger U, Bürgin W, et al. Particulate bioglass as a grafting material in the treatment of periodontal intrabony defects. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:410–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Low SB, King CJ, Krieger J. An evaluation of bioactive ceramic in the treatment of periodontal osseous defects. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1997;17:358–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krish ER, Garg AK. Post-extraction ridge maintenance using the endosseous ridge maintenance implant (ERMI) Compendium. 1994;15:234–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanley HR, Hall MB, Colaizzi F, Clark AE. Residual alveolar ridge maintenance with a new endosseous implant material. J Prosthet Dent. 1987;58:607–13. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(87)90393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson J, Clark AE, Hall M, Hench LL. Tissue response to Bioglass endosseous ridge maintenance implants. J Oral Implantol. 1993;19:295–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atwood DA. Some clinical factors related to rate of resorption of residual ridges. 1962. J Prosthet Dent. 2001;86:119–25. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2001.117609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Veldhuis H, Driessen T, Denissen H, de Groot K. A 5-year evaluation of apatite tooth roots as means to reduce residual ridge resorption. Clin Prev Dent. 1984;6:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quinn JH, Kent JN. Alveolar ridge maintenance with solid nonporous hydroxylapatite root implants. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;85:511–21. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hench LL, Ethridge EC. New York: Academic Press; 1982. Biomaterials: An interfacial approach. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sobolik DF. Alveolar bone resorption. J Prosthet Dent. 1980;10:612–9. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piecuch JF, Topazian RG, Skoly S, Wolfe S. Experimental ridge augmentation with porous hydroxyapatite implants. J Dent Res. 1983;62:148–54. doi: 10.1177/00220345830620021301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hall MB, Stanley HR. Excerpta Medica Proceedings International Congress on Tissue Integration and Maxillofacial Reconstruction, Brussels, 1985. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers BV; 1985. Early clinical trials of 45S5 Bioglass for endosseous alveolar ridge maintenence implants; pp. 248–52. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clark AE, Stanley HR. Clinical trials of bioglass implants for alveolar ridge maintenance. J Dent Res. 1986;65:304. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stanley HR, Hench LL, Bennett CG, Jr, Chellemi SJ, King CJ, 3rd, Going RE, et al. The implantation of natural tooth form bioglass in baboons--long term results. Implantologist. 1981;2:26–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanley HR, Hall MB. Gainesville Fla: University of Florida, JH Miller Health Center; 1983. Research protocol and consent form for project entitled: Preservation of alveolar ridge with the intraosseous implantation of root-shaped cones made of bioglass. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weinstein AM, Klawitter JJ, Cook SD. Implant-bone characteristics of bioglass dental implants. J Biomed Mater Res. 1980;14:23–9. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820140104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gillam DG, Tang JY, Mordan NJ, Newman HN. The effects of a novel Bioglass dentrifice on dentine sensitivity: A scanning electron microscopy investigation. J Oral Rehabil. 2003;30:446. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2002.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Forsback AP, Areva S, Salonen JI. Mineralization of dentin induced by treatment with bioactive glass S53P4 in vitro. Acta Odontol Scand. 2004;62:14–20. doi: 10.1080/00016350310008012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salonen JI. Bioactive glass in dentistry. J Minimum Intervention Dent. 2009:2. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Curtis AR, West NX, Su B. Synthesis of nanobioglass and formation of apatite rods to occlude exposed dentine tubules and eliminate hypersensitivity. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:3740–6. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramashetty Prabhakar A, Arali V. Comparison of the remineralizing effects of sodium fluoride and bioactive glass using bioerodible gel systems. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2009;3:117–21. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2009.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allan I, Newman H, Wilson M. Antibacterial activity of particulate bioglass against supra and subgingival bacteria. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1683–7. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang D, Leppäranta O, Munukka E. Antibacterial effects and dissolution behaviour of six bioactive glasses. J Control Release. 2009;139:118–26. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang X, Jia WT, Gu YI-fei. Borate bioglass based drug delivery of teicoplanin for treating osteomyelitis. J Inorg Mater. 2010;25:293–8. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xie Z, Liu X, Jia W, Zhang C, Huang W, Wang J. Treatment of osteomyelitis and repair of bone defect by degradable bioactive glass releasing vancomycin. J Control Release. 2009;139:118–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Otsuka M, Matsuda Y, Kokubo T, Yoshihara S, Nakamura T, Yamamuro T. A novel skeletal drug delivery system using self-setting bioactive glass bone cement. III: The in vitro drug release from bone cement containing indomethacin and its physicochemical properties. J Control Release. 1994;31:111–9. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ladrón de Guevara-Fernández S, Ragel CV, Vallet-Regí M. Bioactive glass-polymer materials for controlled release of ibuprofen. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4037–43. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Méndez JA, Fernández M, González-Corchón A, Salvado M, Collía F, de Pedro JA, et al. Injectable self-curing bioactive acrylic-glass composites charged with specific anti-inflammatory/analgesic agent. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2381–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Venugopal J, Vadgma P, Sampath Kumar T, Ramakrishna S. Biocomposite nanofibres and osteoblasts for bone tissue engineering. Nanotechnology. 2007:18. [Google Scholar]