Abstract

Background:

There has been an explosive growth of internet use not only in India but also worldwide in the last decade. There is a growing concern about whether this is excessive and, if so, whether it amounts to an addiction.

Aim:

To study the prevalence of internet addiction and associated existing psychopathology in adolescent age group.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study sample comprising of 987 students of various faculties across the city of Mumbai was conducted after obtaining Institutional Ethics Committee approval and permission from the concerned colleges. Students were assessed with a specially constructed semi-structured proforma and The Internet Addiction Test (IAT; Young, 1998) which was self-administered by the students after giving them brief instructions. Dukes Health Profile was used to study physical and psychosocial quality of life of students. Subjects were classified into moderate users, possible addicts, and addicts for comparison.

Results:

Of the 987 adolescents who took part in the study, 681 (68.9%) were female and 306 (31.1%) were males. The mean age of adolescents was 16.82 years. Of the total, about 74.5% were moderate (average) users. Using Young's original criteria, 0.7% were found to be addicts. Those with excessive use internet had high scores on anxiety, depression, and anxiety depression.

Conclusions:

In the emerging era of internet use, we must learn to differentiate excessive internet use from addiction and be vigilant about psychopathology.

Keywords: Dukes health profile, internet addict, internet addiction test

INTRODUCTION

There has been an explosive growth in the use of internet not only in India but also worldwide in the last decade. There were about 42 million active internet users in urban India in 2008 as compared to 5 million in 2000.[1] The internet is used by some to facilitate research, to seek information, for interpersonal communication, and for business transactions. On the other hand, it can be used by some to indulge in pornography, excessive gaming, chatting for long hours, and even gambling. There have been growing concerns worldwide for what has been labeled as “internet addiction.”

The term “internet addiction” was proposed by Dr. Ivan Goldberg in 1995 for pathological compulsive internet use.[2] Griffith considered it a subset of behavior addiction and any behavior that meets the 6 “core components” of addiction, i.e., salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse.[3] While Davis[4] avoided the term internet addiction, referring it as a dependency on psychoactive substances, he instead preferred the term “pathological internet use” (PIU). Young[5] linked excessive internet use most closely to pathological gambling, a disorder of impulse control in DSM IV and adapted the DSM IV criteria to relate to internet use in the Internet Addiction Test developed by her. According to her, various types of internet addiction are cyber-sexual addiction, cyber-relationship addiction, net compulsions, information overload, and computer addiction.[6] Caplan[7] tested Davis’ cognitive behavioral model of PIU. His findings indicated that social isolation plays a greater role in behavioral symptoms of PIU than does the presence of psychopathology. Hence, Caplan suggested replacing the term “pathological internet use” with “problematic internet use.”

The prevalence found by Greenfield[8] was about 6% among the general population, while Scherer[9] found it to be 14% among the college-based population. Surveys conducted online revealed that 4-10% of the users meet the criteria for internet addiction. General population surveys show a prevalence of 0.3-0.7%.[10] The addicted averaged 38.5 h/week on a computer, whereas the non-addicted averaged 4.9 h/week.

Measuring internet addiction was a challenge. Goldberg developed the Internet Addictive Disorder (IAD) Scale by adapting the DSM IV. Brenner[11] developed the Internet-Related Addictive Behavior Inventory (IRABI) comprising of 32 true and false questions. Young initially developed 8-question Internet Addiction Diagnostic Questionnaire (DQ) based on DSM IV. Later, she included 12 new items in addition to the 8 items to formulate an Internet Addiction Test (IAT). Young's IAT is the only available test whose psychometric properties have been tested by Widyanto and McMurran.[12]

In India, use of internet is enormous, especially in the young population. Hence, it was found necessary to study pattern of internet usage in young adults in Indian setting and its relationship with their mental and physical health. With this background, we undertook the present study to take a close look on this issue.

Objective

The aim of the study was to study the prevalence of internet addiction and association of any psychopathology in college going student population in the city of Mumbai.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

The cross-sectional survey was carried out in 3 different colleges in the city of Mumbai during the period of August–September 2009. It covered about 1000 college students (aged 16-18 years) having access to the internet from the past 6 months. The semi-structured proforma along with the scales were distributed in classes, each with roughly 40 students, and necessary instructions were given.

The study was conducted after obtaining the approval from the Institutional Review Board and permission was sought from the college authorities of all the colleges. Of the total 1000 students, 13 could not be included in the study as they were not using internet. Thus, a total of 987 students were finally included in the study.

Tools

The tools used in this study were as follows:

Semi-structured proforma that contained details of demographics, educational qualification and status, purpose of using the internet (by choosing among the options like education, entertainment, business transactions, or social networking), money spent per month, place of access (home, cybercafé, or workplace if working part-time), the time of day when the internet is accessed the most (by choosing between morning, afternoon, evening, or night), and the average duration of use per day. Data was collected from those using internet for at least since last 6 months.

-

The Internet Addiction Test (IAT; Young, 1998) is a 20-item 5-point likert scale that measures the severity of self-reported compulsive use of the internet. Total internet addiction scores are calculated, with possible scores for the sum of 20 items ranging from 20 to 100. The scale showed very good internal consistency, with an alpha coefficient of 0.93 in the present study.

According to Young's criteria, total IAT scores 20-39 represent average users with complete control of their internet use, scores 40-69 represent over-users with frequent problems caused by their internet use, and scores 70-100 represent internet addicts with significant problems caused by their internet use.

The Duke Health Profile is a 17-item generic questionnaire instrument designed to measure adult self-reported functional health status quantitatively during a 1-week time window.[13] It is appropriate for both patient and non-patient adult populations. It can be administered by the respondents themselves or by another person. The administration time is less than 5 min. It is crucial that each question is answered. There are 11 scales with maximum score for each scale being 100 and minimum being 0. Six scales (i.e., physical health, mental health, social health, general health, perceived health, and self-esteem) measure function, with high scores indicating better health. Five scales (i.e., anxiety, depression, anxiety-depression, pain disability) measure dysfunction, with high scores indicating greater dysfunction. Most extensive use was in family practice patients with the broadest spectrum of diagnoses, but it was used in patient populations with specific diagnoses such as insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease, ischemic disease, and impotence. Both internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) and temporal stability (test-retest) testing have supported reliability of the DUKE. Validity has been supported for the DUKE scales by (a) comparison of the DUKE scores with scores of other health measures for the same patients, (b) comparison of DUKE scores between patient groups having different clinical diagnostic profiles and severity of illness, and (c) prediction of health-related outcomes by DUKE scores. Convergent and discriminant validity have been shown when comparing with other instruments.

RESULTS

In the present study, out of 1000 students, 13 were excluded and the remaining 987 adolescents who participates included 681 (68.9%) females and 306 (31.1%) males. Subjects had more girls than boys as the data was collected during routine lectures and the attendance of girls might have been more. The mean age of adolescents was 16.82 (standard deviation, 0.61). The subjects belonged to different streams: 33.5% to science, 30.3% to commerce, and 36.2% to arts.

The SPSS version 16.0 was used for statistical analysis of the data collected. Using Young's original criteria, the users were divided into groups: 74.5% as moderate users, 24.8% as possible addicts, and 0.7% as addicts. Significant usage differences were evident based on the gender of user. Males in comparison to females were significantly more likely to be addicted (x2=10.2, P=0.006). Moderate users and the possible addicts used the internet mostly for social networking, academic purposes, chatting, emailing, gaming, and downloading media files and pornography. The purpose of using the internet was significantly different for addicts. They indulged more in social networking, chatting, and downloading media files (x2=76, P<0.001).

Significantly, most of the addicts used the internet mostly in the evening and nights as compared to other users who used it in the mornings and afternoons as well (x2=26.4, P=00019). Interesting findings were noted with respect to the place of accessing internet. About half of the adolescents with addiction were also working part-time and used the workplace to access the internet. This finding too was statistically significant (x2=144, P<0.001). In this study, no significant relationship was found between internet addiction and the hours of use per day. Moreover, the criteria used in IAT does not take into consideration the exact duration of use. Losing track of time while being online and staying online longer than intended are more likely to be seen in addicts.

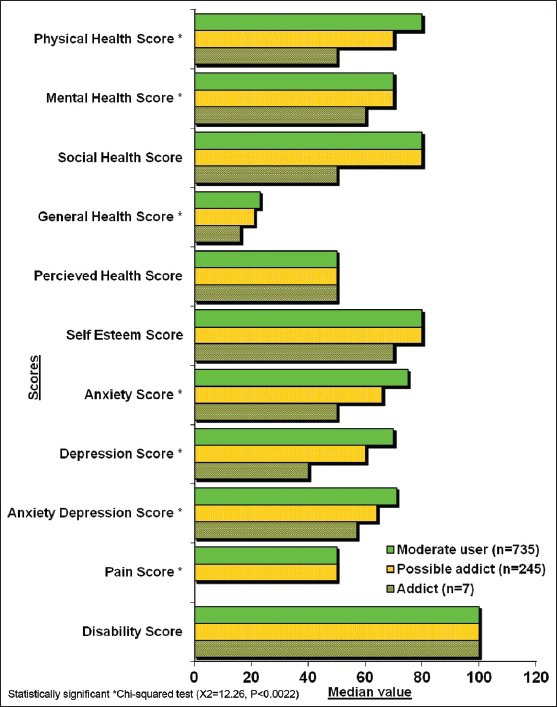

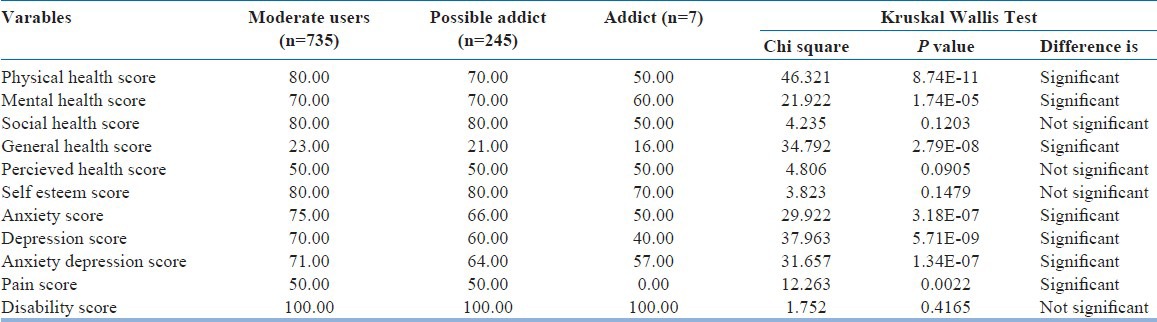

Using Duke's Health profile, it was found that addicts have poor mental, physical, and mental health score [Figure 1]. No significant relationship was found between self-esteem score and internet addiction. Addicts had high anxiety, depression, and anxiety depression score (x2=12.26, P<0.0022) [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Internet use and psychopathology using Dukeæs health profile

Table 1.

Internet use and psychopathology as per dukes health profile

DISCUSSION

A number of studies have been conducted across the world, especially among adolescents with respect to internet addiction. This study is a preliminary step toward understanding the extent of internet addiction among college students in India.

Nalwa and Anand[14] investigated the extent of internet addiction in school children in India. The findings of the present study corroborates with previous studies stating that addiction is more common in males than in females[15](Anderson et al.).[16] Also, the finding that addicts are more likely to use their workplace to access internet is comparable to “Internet Abuse at workplace” reported by Young and Case.[17] But the study done by Young and Case covered managers and company presidents. This could be a confounding factor for comparison as our study had students as subjects. Employers have found that employees with access to the internet at their desks spend a considerable amount of their working day engaging in non-work-related internet use (Beard, 2002).[18]

In a study done previously, Young[5] concluded that depression assessment should be done in suspected cases of PIU. Although it is not clear whether depression precedes the development of internet abuse or it is a consequence,[19] yet assessment of the same is imperative. In 2005, a study by Nemiz et al.[15] dealt with British university students showed that those students who were pathological internet users had low self-esteem and were socially inhibited online.[19] Young[5] showed that withdrawal from significant real-life relationships is a consequence of pathological internet users.

CONCLUSION

In the last one decade, internet has become an integral part of our life. We wanted to find the prevalence of internet addiction in Indian college population. It can put into three groups using Young's original criteria: 74.5% as moderate users, 24.8% as possible addicts, and 0.7% as addicts. Those towards the addict part of spectrum reported had high anxiety, depression, and anxiety depression score.

Implications

In the emerging era, where young people have been more exposed to the internet and use online activity as an important form of social interaction. However, it may still remain a matter of debate whether to call internet addiction a distinct disorder by itself or a behavioral problem secondary to another disorder. At present, DSM IV has no accepted criteria to diagnose or label internet addiction. Whether or not we will have any such diagnosis included in the future is yet to be seen.[20] In future, if it is added, it is more likely to be classified as an impulse control disorders not elsewhere classified rather than in the diagnostic criteria for substance dependence.[21] By studying the association of internet usage and its effects on human behavior, we can formulate interventions like setting boundaries and detecting early warning signs of underlying psychopathology at the earliest.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Internet and Mobile association of India. I-Cube 2008 Study. [Last accessed on 2010 Mar 12]. Available from: http://www.iamai.in/Upload/Research/I-Cube_2008_Summary_Report_30.pdf .

- 2.Goldberg I. Internet Addiction 1996. [Last accessed on 2010 Mar 22]. Available from: http://web.urz.uniheidelberg.de/Netzdienste/anleitung/wwwtips/8/addict.html .

- 3.Mark G. Does internet and computer “addiction” exist? Some case study evidence. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2000;3:211–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis RA. A cognitive behavioral model of pathological internet use (PIU) Comput Hum Behav. 2001;17:187–95. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young KS. Internet Addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1998;3:237–44. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young KS. Internet addiction: A new clinical phenomenon and its consequences. Am Behav Sci. 2004;48:402–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caplan SE. Relations among lonliness, social anxiety, and problematic internet use. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2007;10:234–42. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenfield D. Paper presented at the 107th Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association. Massachusetts: Boston; 1999. Aug 22, Internet addiction: Disinhibition, accelerated intimacy and other theoretical considerations. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scherer K. College life online: Healthy and unhealthy Internet use. J Coll Dev. 1997;38:655–65. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. Kaplon and Sadock Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry; pp. 1063–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brenner V. Psychology of computer use: XLVII. Parameters of Internet Use, abuse, and addiction: The first 90 days of the Internet Usage Survey. Psychol Rep. 1997;80:879–82. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1997.80.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Widyanto L, McMurran M. The psychometric properties of the internet addiction test. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004;7:443–50. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2004.7.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuntermann MF. The duke health profile (DUKE) Rehabilitation (Stuttg) 1997;36:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanwal N, Archana PA. Internet addiction in students: A cause of concern. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2003;6:653–6. doi: 10.1089/109493103322725441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niemz K, Griffiths M, Banyard P. Prevalence of pathological internet use among university students and correlations with self-esteem, the general health questionnaire (GHQ), and disinhibition. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2005;8:562–70. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson KJ. Internet use among college students: An exploratory study. J Am Coll Health. 2001;50:21–6. doi: 10.1080/07448480109595707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young KS, Case CJ. Internet abuse in the workplace: New trends in risk management. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004;7:105–11. doi: 10.1089/109493104322820174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beard K. Internet addiction. Current status and implications for employees. J Employ Couns. 2002;39:2–11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young KS. The relationship between depression and internet addiction. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1998;1:25–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Block JJ. Issues for DSM V: Internet addiction. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:306–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07101556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shapira NA, Goldsmith TD, Keck PE, Jr, Khosla UM, McElroy SL. Psychiatric features of individuals with problematic internet use. J Affect Disord. 2000;57:267–72. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]