Abstract

Objectives:

To study the prescription pattern of psychotropic drugs in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Eastern India with special reference to polypharmacy.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 411 patients were included in the study through systematic sampling. Patients were diagnosed by a Consultant Psychiatrist before inclusion in the study using a semi-structured interview schedule based on the International Classification of Disease (ICD), classification of mental and behavioral disorders, 10th version). The most recently prescribed psychopharmacological medication of those patients was studied. A checklist to assess the pattern of prescription and evaluate reasons of polypharmacy was filled up by the prescribing consultant.

Results:

About 76.6% of the patients received polypharmacy in the index study. Males were more exposed to polypharmacy compared to women (80.93% vs. 70.85%). Gender and diagnosis had a predictive value with regard to the polypharmacy. Polypharmacy was more common in organic mental disorders (F0), psychoactive substance abuse disorders (F1), psychotic disorders (F2), mood disorders (F3) and in childhood, and adolescent mental disorders (F9). Most frequently, antipsychotic drugs were prescribed followed by tranquilizers/hypnotics and anticholinergics. Antidepressants (35.13%) were more commonly prescribed as monotherapy. Anticholinergics (100%) and tranquilizers/hypnotics (96.7%) were the drugs more commonly used in combination with other psychotropics. The three most common reasons for prescribing polypharmacy were augmentation (43.8%) of primary drug followed by its use to prevent adverse effects of primary drug (39.6%) and to treat comorbidity (34.9%).

Conclusions:

Polypharmacy is a common practice despite the research based guidelines suggest otherwise. More vigorous research is needed to address this sensitive issue.

KEY WORDS: Polypharmacy, prescription patterns, psychotropics

Introduction

The concurrent use of multiple psychoactive medications in a single patient, i.e., polypharmacy, is increasingly common and debatable contemporary practice in clinical psychiatry and probably based more upon experience than evidence.[1,2] According to Preskorn and Lacey clinicians there are several reasons for polypharmacy: to treat two pathophysiologically distinct but co morbid illnesses in the same patient; to prevent an adverse effect produced by the primary drug; to provide acute amelioration while awaiting the delayed effect of another medication (e.g., using lorazepam in acute mania while waiting for the antimanic effects of lithium to exert themselves); to treat intervening phases of an illness (e.g., adding an antidepressant to a mood stabilizer when a bipolar patient develops a depressive episode); and to boost or augment the efficacy of the primary treatment (e.g., combining a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and desipramine to treat a patient with major depression).[3]

Various studies have looked into different aspects of polypharmacy, e.g., incidence, prevalence, rationality, profile of subjects receiving polypharmacy etc.[4,5,6] Two reviews on the use of polypharmacy concluded that despite strong recommendation by experts to employ monotherapy whenever possible, the prevalence of antipsychotic polypharmacy (APP) has greatly increased, particularly since the advent of the Second Generation Antipsychotics (SGA).[7,8] There was very few studies have evaluated the prescription pattern and the issue of polypharmacy in psychiatric patients from India. In view of this, an attempt has been made to study the pattern of drug combinations prescribed to psycahtric patient and analyze the same.

Materials and Methods

Setting

This study was conducted in the out-patient department (OPD) of Mental Health Institute, S.C.B Medical College, Cuttack, a Tertiary Care Hospital, providing specialist clinical care to about ten districts of Orissa adjoining Cuttack and West Bengal and Chattishgarh.

Study Population

The study sample was collected from the daily out-patient attendance of 70 to 80 over a 1-month period using systematic sampling procedure. Every fifth patient attending the OPD was included in our study. A total 411 patients were included in study.

Instruments

The following instruments were used.

Socio-demographic profile sheet: Specially developed for this study was used to record the relevant socio-demographic data on age, gender, education, marital status, and locality.

A semi-structured interview schedule based on the ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioral disorders practiced at Mental Health Institute, S.C.B Medical College, Cuttack.

A checklist specially, developed for the study to assess and evaluate polypharmacy or combination of drugs and reasons for prescribing it.

Procedure

Every fifth patient attending the OPD was examined and diagnosed by a consultant psychiatrist before inclusion in the study using a semi-structured interview. This was based on the ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioral disorders which include: Organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders (F0); mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance abuse (F1); schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (F2); mood (affective) disorders (F3); neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders (F4); behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors (F5); disorders of the adult personality and behavior (F6); and mental retardation (F7); behavioral and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence (F9). The recently prescribed psychopharmacological medication, were divided into groups such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, tranquilizers/hypnotics, anticholinergics/antiparkinsonian-drugs. A checklist, to assess the pattern of prescription and evaluate reasons of polypharmacy or combination of drugs, was attached with the OPD ticket and was filled up by the prescribing consultant. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board and Research Committee of the Institute (approval no. SCB/Synopsis/2007/Psy/02).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science Version 14 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The descriptive analysis was computed in terms of mean and standard deviation. Chi-square test was used to determine the predictive value of patient variables with regard to the prescription of polypharmacy. Z-test was applied to find out the statistical significance of the reasons of polypharmacy according to the diagnosis and in total.

Results

Socio-Demographic and Clinical Profile of the Sample

Majority of patients were men (57.4%), and in 25-45 years age group (44.5%). Most of the patients were having diagnosed most schizophrenic psychosis (ICD-10: F2) (45.9%), followed by mood disorders, substance abuse disorders neurotic stress, and somatoform disorder.

Pattern of Prescription of Psychotropic Medications

Antipsychotics were the most commonly prescribed psychotropic medication followed by drug prescribed for psychoactive substance use disorders (F1) (90.6%), schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders (F2) (100%), mental retardation (F7) (100%), and behavioral and emotional disorders in childhood and adolescence (F9) (83.3%). Antidepressants were prescribed in subjects with mood disorders (F3) (57.9%), and neurotic, stress related and somatoform disorders (F4) (73.3%). Four-fifth of the subjects with organic mental disorder and psychotic disorders received hypnotics.

Pattern of Monotherapy Versus Polypharmacy

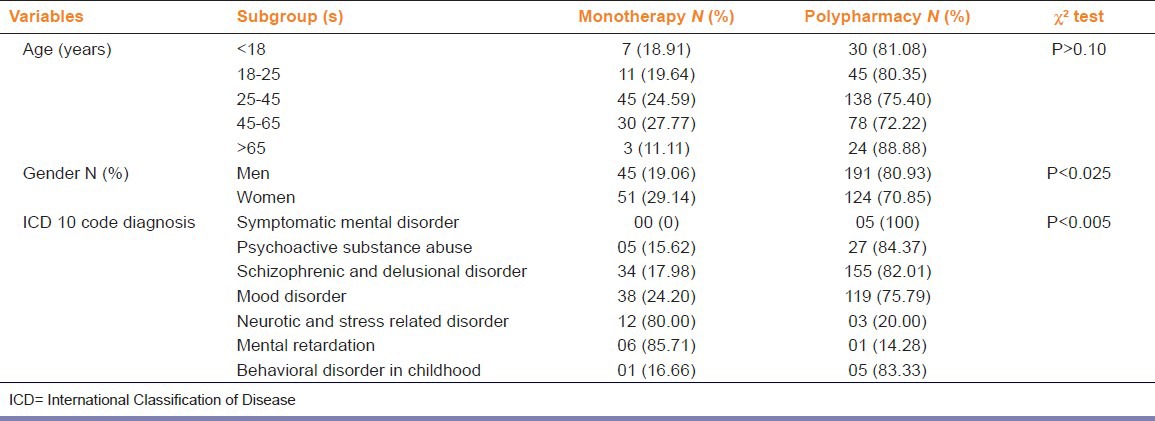

Polypharmacy with psychoactive drugs was more prevalent than monotherapy among all age groups with highest in those with aged above 65 years (88.8%). However, it was observed that age has no predictive value with regard to prescription of polypharmacy (P > 0.10). Polypharmacy was more prevalent than monotherapy among both genders with four-fifth of the men receiving polypharmacy contrary to 70% women receiving the same. Gender had a predictive value with regard to prescription of polypharmacy (P < 0.025). The percentage of patients receiving polypharmacy was more than monotherapy in : o0 rganic mental disorders (F0) (100%); psychoactive substance use disorders (F1) (84.3%); schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders (F2) (82%); mood disorders (F3) (75.7%) and in childhood and adolescent disorders (F9) (83.3%). The monotherapy was more common in neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (F4) (80%) and mental retardation (F7) (85.7%). Moreover, diagnosis also had a predictive value with regard to prescription of polypharmacy (P <.005). In particular, diagnoses were the most reliable predictor [Table 1].

Table 1.

Pattern of monotherpy and polypharmacy according to patient demography and clinical diagnosis

Reasons for Polypharmacy

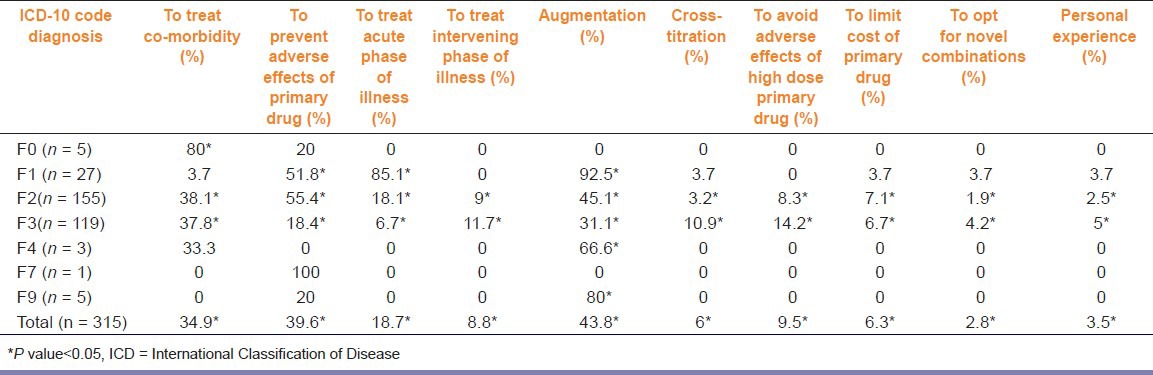

In patients with organic mental disorders (F0) and substance use disorders (F1) treating co-morbidity (80%) and augmentation (92.5%) were the most common reasons for polypharmacy respectively. In patients with psychotic disorders (F2) to prevent adverse effects of primary drug (55.4%), augmentation (45.1%) and to treat co-morbidity (38.1%) were the three most common reasons given by clinicians for prescribing polypharmacy. In patients with mood or affective disorders (F3) to treat co-morbidity (37.8%) was the most common reason for polypharmacy. The other two important reasons for polypharmacy in this group were augmentation (31.1%) and to prevent adverse effects of primary drug (18.4%). On applying Z-test all the reasons mentioned in the checklist were found to be significant contributors of polypharmacy in these two categories (F2 and F3) of mental disorders [Table 2].

Table 2.

Reason for prescribing polypharmacy in psychiatric patients (n = number of patients in polypharmacy according to diagnosis)

Overall, augmentation was the most (43.8%) common reasons for polypharmacy and all the reasons mentioned in our checklist were significantly contributing to it.

Discussion

The present study shows that polypharmacy was more in men than women. However, no clear relationship was seen between age and polypharmacy with psychotropic drugs, as reported in other studies.[9,10] A possible explanation can be the different diagnostic profile of the patients and epidemiological distribution of psychiatric diagnoses in the population. The diagnosis was most reliable predictor for polypharmacy. The patients suffering from schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders were the ones most predisposed to polypharmacy.

Antipsychotics were preferentially prescribed across all diagnostic categories except for mood and anxiety disorders. Mood stabilizers and tranquilizers were almost always combined with other psychotropic medications. Similar pattern of prescription has been observed in other studies as well.[11]

Drug combinations often represent “uncontrolled experiments,” with unknown potential for toxic effects.[12] However, a recent study on patients with schizophrenia found that, APP was not associated with increased mortality whereas, the use of benzodiazepines was associated with marked increase in mortality.[13] Although, irrational polypharmacy occurs too frequently but in many instances it is necessary to manage the patient with multiple medications and that makes rational polypharmacy.[1,7,14] The classic example is the use of benztropine to manage side effects from haloperidol. Another example is the use of lithium to augment a partial response to an antidepressant and thus, increase its efficacy.[15] In addition to these reasons, clinicians may use polypharmacy in patients as combination therapy for symptom relief while using lower doses of two antipsychotics with differing side-effect profiles.[7] Concerns with polypharmacy include the possibility of cumulative toxicity and increased vulnerability to adverse events as well as adherence issues which emerge with increasing regimen complexity.[16]

The present study showed that polypharmacy was used to treat co morbidity such as organic mental disorders, psychotic disorders, mood disorders. Moreover, the patients suffering from chronic schizophrenic psychosis and mood disorders usually have co-morbid illnesses along with their primary diagnosis.

To prevent adverse effects of primary drug was another reason which contributed significantly to polypharmacy in patients with psychoactive substance use disorders, psychotic disorders, mood disorders, and in total patients receiving polypharmacy. For example, anticholinergic to prevent extra pyramidal side effects due to antipsychotics

To treat acute phase of illness was another significant reason for which polypharmacy was instituted in patients with psychoactive substance use disorders, psychotic disorders, mood disorders, and total polypharmacy patients. This reason means to provide acute amelioration while awaiting the delayed effect of another medication, e.g., using tranquilizers/hypnotics in acute manic violent patients while awaiting the antimanic effects of lithium to take over.

To treat intervening phase of illness was found to be significant reason in patients with psychotic disorders (F2), mood disorders (F3), and total polypharmacy patients. This factor is important when a patient of bipolar mood disorder maintained on a mood stabilizer develops a depressive episode and clinician adds an antidepressant to it or an injectable antipsychotic is added to control agitation in a patient of chronic schizophrenia that was doing well on oral medications.

Augmentation was found significant in patients with psychoactive substance use disorders, psychotic disorders, mood disorders, and neurotic disorders, disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence and total polypharmacy patients. Cross-titration was found significant in patients with psychotic disorders (F2), mood disorders (F3), and total polypharmacy patients. Cross titration is seen as psychotropic drugs are often combined when a patient is switched from one to another, with the new drug titrated up while the first drug is tapered with the plan to discontinue it. To avoid adverse effects of primary drug was found significant in patients with psychotic disorders (F2), mood disorders (F3), and total polypharmacy patients. Whereas use of two drugs in combination is often expected to cause more side-effects than one drug alone, in certain situations (e.g., dealing with side effects such as sedation or hypotension). To limit the cost of primary drug was found to be a significant reason in patients with psychotic disorders (F2), mood disorders (F3), and total polypharmacy patients. To limit the cost of the therapy, clinician changes a high cost SGA, e.g., olanzapine to a low-cost high potency first generation antipsychotic e.g., haloperidol, which necessitates it to be combined with an anticholinergic.

To opt for novel combinations and personal experience were found significant in patients with psychotic disorders (F2), mood disorders (F3) and total polypharmacy patients. Even with advent of novel antipsychotics and antidepressants, a “panacea” for resistant or non-responding patients still eludes psychotropic armamentarium. Therefore, clinicians often try out novel combinations or depend on their personal experience to battle it out.

Limitations and Future Direction

The research involves patients attending the outpatient psychiatry department of a Tertiary Care Center in Eastern India. Therefore, results of this study cannot be representative of national data. The hospital resources (e.g., availability of free medicines from hospital) govern the issue of polypharmacy, which has not been considered in this research. The duration, severity and nature of illness which could have possibly influenced the treatment decision were largely ignored. Future studies need to address the above issues.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Edlinger M, Hausmann A, Kemmler G, Kurz M, Kurzthaler I, Walch T, et al. Trends in the pharmacological treatment of patients with schizophrenia over a 12 year observation period. Schizophr Res. 2005;77:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stahl SM. Antipsychotic polypharmacy: Evidence based or eminence based? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:321–2. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.2e011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preskorn SH, Lacey RL. Polypharmacy: When is it rational? J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13:97–105. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000265766.25495.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McIntyre RS, Jerrell JM. Polypharmacy in children and adolescents treated for major depressive disorder: A claims database study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:240–6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glezer A, Byatt N, Cook R, Jr, Rothschild AJ. Polypharmacy prevalence rates in the treatment of unipolar depression in an outpatient clinic. J Affect Disord. 2009;117:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, Kane JM, Leucht S. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:443–57. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pandurangi AK, Dalkilic A. Polypharmacy with second-generation antipsychotics: A review of evidence. J Psychiatr Pract. 2008;14:345–67. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000341890.05383.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardos G. Antipsychotic polypharmacy or monotherapy? Neuropsychopharmacol Hung. 2005;7:72–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMillan DA, Harrison PM, Rogers LJ, Tong N, McLean AJ. Polypharmacy in an Australian teaching hospital. xsPreliminary analysis of prevalence, types of drugs and associations. Med J Aust. 1986;145:339–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolan L, O’Malley K. Prescribing for the elderly: Part II. Prescribing patterns: Differences due to age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:245–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb01809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De las Cuevas C, Sanz EJ. Polypharmacy in psychiatric practice in the Canary Islands. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trumic E, Pranjic N, Begic L, Becic F, Asceric M. Idiosyncratic adverse reactions of most frequent drug combinations longterm use among hospitalized patients with polypharmacy. Med Arh. 2012;66:243–8. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2012.66.243-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tiihonen J, Suokas JT, Suvisaari JM, Haukka J, Korhonen P. Polypharmacy with antipsychotics, antidepressants, or benzodiazepines and mortality in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:476–83. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stahl SM. Antipsychotic polypharmacy: Never say never, but never say always. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125:349–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kingsbury SJ, Yi D, Simpson GM. Psychopharmacology: Rational and irrational polypharmacy. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1033–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.8.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray MD, Kroenke K. Polypharmacy and medication adherence: Small steps on a long road. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:137–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]