Abstract

Aims:

To examine the cross-sectional relationship between blood pressure (BP) and (1) in vivo insulin sensitivity (IS) and (2) circulating adiponectin levels in overweight adolescents, and to determine if these relationships are driven by adiposity.

Methods

Sixty-five white pubertal overweight adolescents underwent a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp to measure IS. Body composition and abdominal adiposity were determined by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry and computed tomography scan. BP was measured by an automated sphygmomanometer every 10 min over 1 h, between 06:00 and 07:00 a.m.

Results

In vivo IS was not associated with BP after adjustment for adiposity measurements (body mass index, percentage body fat or abdominal adiposity). However, adiponectin was inversely related to systolic BP independent of adiposity.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that in overweight adolescents the relationship between in vivo IS and systolic BP is mediated through adiposity. However, the association between adiponectin and BP is independent of adiposity suggestive of a potential modulatory role of adiponectin in BP regulation.

Key Words: Blood pressure, Insulin sensitivity, Adiponectin, Obesity, Adolescents, Adipose tissue

Introduction

The prevalence of childhood obesity has increased greatly during the past three decades in most industrialized countries [1]. Childhood obesity often has serious consequences, including insulin resistance, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, fatty liver disease and psychosocial complications [2]. Furthermore, childhood and adolescent obesity is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease in adulthood [3,4].

Similar to adults, the prevalence of hypertension in children is threefold higher in obese children than in non-obese children [5]. In adults, hypertension has been associated with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia [6]. In children, some studies suggest that low insulin sensitivity (IS) is a predictor of high blood pressure (BP) [7]. As high BP is associated with higher body mass index (BMI) [8] and higher adiposity [9,10], it is not clear if the relationship between IS and BP is a consequence of obesity and/or body fat distribution, or is a direct relationship. Additionally, adiponectin, an adipose tissue-derived protein with insulin-sensitizing and antiatherogenic properties, has been associated with BP in adults [11,12,13] and adolescents [14,15].

Therefore, we aimed (1) to examine the relationship between BP, under controlled research conditions, and in vivo IS (measured with the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp) and circulating adiponectin levels in non-diabetic overweight and obese white adolescents, and (2) to determine whether or not these relationships are driven by adiposity [BMI, percentage body fat (%BF), visceral adipose tissue (VAT), subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT)].

Subjects and Methods

Participants consisted of 65 white pubertal overweight and obese but otherwise healthy youths, aged 9 to <18 years, who were recruited through newspaper advertisements and fliers posted on bus routes, the university campus and children's recreational areas in Pittsburgh. Exclusion criteria included diabetes and the use of medications that influence glucose, BP or lipid metabolism. Studies took place at the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh NIH-funded Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center (PCTRC) after institutional review board approval. Participants and their parents gave written informed consent. The participants’ health was assessed by medical history, physical examination, and routine hematological and biochemical studies. Pubertal development was assessed using Tanner criteria.

Body weight and height were measured in the PCTRC using standardized equipment. Overweight was defined as BMI percentile ≥85 to <95 and obesity as BMI percentile ≥95 for age and gender.

Blood Pressure Measurement

Participants were admitted to the PCTRC the afternoon before the morning of the clamp experiment. The appropriate cuff size was chosen to cover two-thirds of the length of the upper arm. Measurements were performed as reported by us before [16] with an automated sphygmomanometer (Dinamap Procare 400; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, Wisc., USA) every 10 min for 1 h between 06:00 and 07:00 a.m. while the patients were resting in the recumbent position in bed. The mean of seven measurements during the hour was the outcome for statistical analysis.

All 65 youths had a computed tomography to determine abdominal and subcutaneous adiposity, and a dual energy X-ray absorptiometry to assess body composition, as described previously [17]. All participants underwent a 3-hour hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp after 10–12 h of overnight fasting. Briefly, intravenous crystalline insulin (Humulin; Lilly, Indianapolis, Ind., USA) was infused at a constant rate of 80 mU·m−2·min−1 and plasma glucose was clamped at 100 mg/dl with a variable rate infusion of 20% dextrose as described by us before [17].

Biochemical Measurements

Plasma glucose was measured using a glucose analyzer (YSI, Yellow Springs, Ohio, USA), and insulin concentrations were measured by radioimmunoassay [17]. Adiponectin was measured using a commercially available radioimmunoassay kit (Linco Research, St. Louis, Mo., USA). The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 3.6 and 9.3% for low and 1.8 and 9.3%, respectively, for high serum concentrations, as reported by us [18].

Calculations

Insulin-stimulated glucose disposal was calculated using the average exogenous glucose infusion rate during the final 30 min of the clamp [17]. IS was calculated by dividing the insulin-stimulated glucose disposal rate by steady-state plasma insulin concentrations during the last 30 min of the clamp multiplied by 100, as described previously [17].

Statistical Analysis

To assess the relationship between BP, IS and adiponectin, bivariate Pearson's or Spearman's correlations were used depending on data distribution. Partial correlation analysis was used to adjust for adiposity measurements (BMI, %BF, VAT and SAT). The relationship between IS and BP was examined through multiple linear regression analysis in five separate models (see table 2). All models were adjusted for height, sex, age and Tanner stage. The first model tested the relationship of IS with systolic BP (SBP) without adjustment for weight or body composition. In models 2–5, in order to adjust for weight or body composition parameters, BMI, %BF, VAT and SAT were added as independent variables, respectively. Finally, to determine the independent contribution of adiponectin to SBP (see table 3), adiponectin was added as an independent variable to the regression models used in table 2. All statistical assumptions were met. Data are presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The statistical analysis was done using PASW Statistics, Version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill., USA).

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression analysis for SBP (mm Hg), the dependent variable, adjusted for height, sex, age and Tanner stage

| Independent variables | B | 95% CI | p | Partial r | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | IS, mg/kg FFM/min per μU/ml | −0.68 | –1.22 to −0.15 | 0.013 | −0.315 |

| Model 2 | IS, mg/kg FFM/min per μU/ml | −0.27 | −0.87 to 0.32 | 0.360 | −0.120 |

| BMI | 0.65 | 0.16 to 1.14 | 0.010 | 0.331 | |

| Model 3 | IS, mg/kg FFM/min per μU/ml | −0.43 | –1.01 to 0.15 | 0.140 | −0.193 |

| %BF | 0.39 | 0.01 to 0.77 | 0.043 | 0.262 | |

| Model 4 | IS, mg/kg FFM/min per μU/ml | −0.32 | −0.92 to 0.29 | 0.302 | −0.139 |

| VAT, cm2 | 0.10 | 0.02 to 0.18 | 0.015 | 0.320 | |

| Model 5 | IS, mg/kg FFM/min per μU/ml | −0.44 | –1.08 to 0.19 | 0.165 | −0.187 |

| SAT, cm2 | 0.02 | −0.01 to 0.04 | 0.132 | 0.202 | |

IS = Insulin sensitivity

FFM = fat-free mass

VAT = visceral adipose tissue

SAT = subcutaneous adipose tissue.

p < 0.05 is indicated in bold.

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression analysis for SBP (mm Hg), the dependent variable, adjusted for insulin sensitivity (mg/kg FFM/min per μU/ml), height, sex, age and Tanner stage

| Independent variables | B | 95% CI | p | Partial r | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Adiponectin, μg/ml | –1.21 | –1.82 to −0.61 | <0.001 | −0.456 |

| Model 2 | Adiponectin, μg/ml | −0.92 | –1.56 to −0.28 | 0.006 | −0.347 |

| BMI | 0.49 | 0.05 to 0.93 | 0.030 | 0.276 | |

| Model 3 | Adiponectin, μg/ml | –1.03 | –1.73 to −0.34 | 0.004 | −0.385 |

| %BF | 0.32 | −0.10 to 0.74 | 0.136 | 0.207 | |

| Model 4 | Adiponectin, μg/ml | −0.85 | –1.54 to −0.16 | 0.016 | −0.311 |

| VAT, cm2 | 0.09 | 0.01 to 0.16 | 0.027 | 0.287 | |

| Model 5 | Adiponectin, μg/ml | –1.09 | –1.76 to −0.43 | 0.002 | −0.398 |

| SAT, cm2 | 0.01 | −0.01 to 0.03 | 0.281 | 0.143 | |

VAT = Visceral adipose tissue

SAT = subcutaneous adipose tissue. p < 0.05 is indicated in bold.

Results

Subjects’ Clinical, Physical and Biochemical Characteristics

A total of 65 healthy overweight and obese white adolescents were studied. The participants’ clinical characteristics, body composition, metabolic profile and BP measurements are depicted in table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ clinical characteristics, body composition, metabolic profile and BP

| Total | Range | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 65 | 29 | 36 | |

| Age, years | 13.4 ± 1.9 | 9.8–17.9 | 13.9 ± 1.5 | 13.0 ± 2.1 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 29 | |||

| Female | 36 | |||

| Puberty | ||||

| Tanner II-III | 33 | 18 | 15 | |

| Tanner IV-V | 32 | 11 | 21 | |

| Height, cm | 161.5 ± 10.1 | 140.0–183.1 | 167.3 ± 8.8 | 156.8 ± 8.6 |

| Body composition | ||||

| BMI | 31.5 ± 6.2 | 20.4–45.7 | 30.8 ± 5.6 | 32.1 ± 6.7 |

| BMI percentile | 96.5 ± 4.1 | 85.0–99.9 | 96.5 ± 3.9 | 96.4 ± 4.3 |

| Fat mass, kg | 33.7 ± 11.8 | 10.5–61.5 | 32.7 ± 11.9 | 34.6 ± 11.8 |

| FFM, kg | 45.4 ± 10.6 | 26.9–76.6 | 50.3 ± 10.3 | 41.4 ± 9.2 |

| %BF | 40.7 ± 7.6 | 20.6–52.9 | 37.3 ± 7.5 | 43.4 ± 6.5 |

| VAT, cm2 | 70.1 ± 36.0 | 13.9–201.1 | 70.6 ± 32.7 | 69.7 ± 39.0 |

| SAT, cm2 | 421.3 ± 164.0 | 103.5–726.8 | 400.3 ± 161.6 | 438.6 ± 166.3 |

| Metabolic profile | ||||

| Fasting glucose, mg/dl | 93.2 ± 7.5 | 74.0–114.0 | 93.6 ± 7.0 | 92.8 ± 8.0 |

| Fasting insulin, μU/ml | 33.8 ± 27.5 | 7.3–127.3 | 30.3 ± 19.8 | 36.8 ± 32.8 |

| IS, mg/kg/min per μU/ml | 3.5 ± 3.0 | 0.4–14.0 | 4.4 ± 3.7 | 2.8 ± 1.9 |

| IS, mg/kg FFM/min per μU/ml | 6.2 ± 4.7 | 0.6 − 24.1 | 7.4 ± 5.8 | 5.2 ± 3.4 |

| Adiponectin, μg/ml | 8.5 ± 4.3 | 2.0 − 22.5 | 9.3 ± 4.8 | 8.1 ± 4.0 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 132.4 ± 81.2 | 48.0 − 416.0 | 148.2 ± 109.4 | 119.3 ± 44.4 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 41.6 ± 7.2 | 26.8 − 59.2 | 43.1 ± 7.1 | 40.3 ± 7.2 |

| Blood pressure | ||||

| SBP, mm Hg | 112.4 ± 10.4 | 87.0 − 144.7 | 113.9 ± 10.2 | 111.2 ± 10.5 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 61.7 ± 7.5 | 46.0 − 82.0 | 63.3 ± 8.0 | 60.4 ± 6.9 |

Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± SD. VAT = Visceral adipose tissue; SAT = subcutaneous adipose tissue; FFM = fat-free mass; IS = insulin sensitivity.

Blood Pressure and Insulin Sensitivity

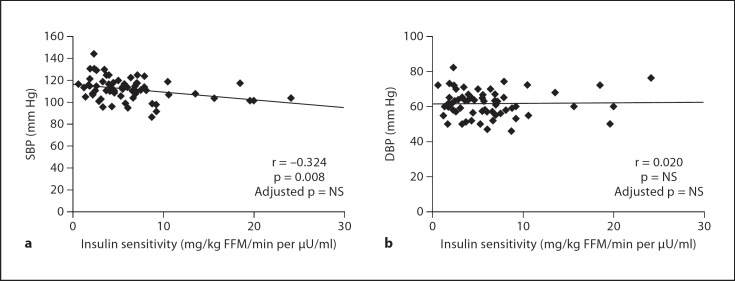

IS correlated inversely with SBP (r = −0.324; p = 0.008). However, the significance of this association disappeared after adjustment for any of the adiposity measurements (BMI, %BF, VAT and SAT) (fig. 1). IS did not correlate with diastolic BP (DBP) (r = 0.020; p = NS). Fasting insulin and fasting glucose/insulin ratio, as surrogate markers of IS, did not correlate with SBP or DBP (data not shown). To determine the independent contribution of IS to SBP, five multiple linear regression analyses were performed (table 2). All models were adjusted for height, sex, age and Tanner stage. Without adjustment for body composition parameters, IS showed an independent relationship to SBP. However, the significance of this relationship disappeared when adjusting for BMI, %BF, VAT or SAT, since BMI, %BF and VAT are independent predictors of SBP (table 2).

Fig. 1.

Correlation between IS (mg/kg FFM/min per μU/ml) and a SBP and b DBP (mm Hg) before and after adjustment for adiposity measurements (BMI, %BF, VAT and SAT).

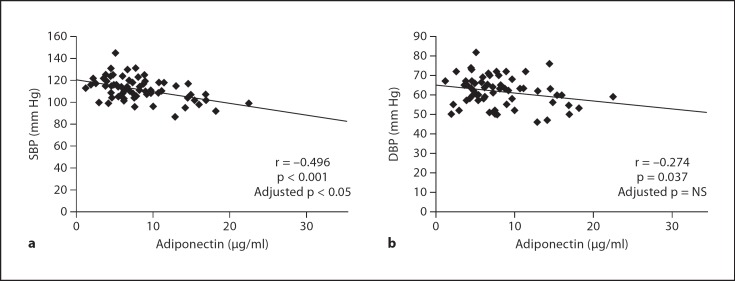

Blood Pressure and Adiponectin

In univariate analysis, adiponectin levels correlated inversely with both SBP (r = −0.496; p < 0.001) and DBP (r = −0.274; p = 0.037) (fig. 2). After adjustment for height, sex, age, Tanner stage and IS, circulating adiponectin levels showed a significant relationship to SBP independent of adiposity measurements (BMI, %BF, VAT and SAT) (table 3), but not to DBP (data not shown). Pulse pressure (SBP-DBP) and mean BP (2/3 DBP + 1/3 SBP) did not correlate with IS or adiponectin (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Correlation between circulating adiponectin levels (μg/ml) and a SBP and b DBP (mm Hg) before and after adjustment for adiposity measurements (BMI, %BF, VAT and SAT).

Discussion

The present study advances previous observations of the relationship between IS and BP by demonstrating that adiposity is an important determinant underlying the observed relationship between IS and SBP. Also, the present study demonstrates the relationship of circulating adiponectin levels with SBP independent of adiposity in white overweight adolescents.

Few studies have assessed the relationship between IS and BP in children. Most of them have used estimates of IS, like fasting insulin [19,20], or the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) [21]. One study used the minimal model with a tolbutamide-modified glucose tolerance test [7] and another used the clamp technique [22], but neither had evaluation of abdominal fat distribution. Although in some studies the association between IS and BP seems to be independent of body composition [7], other studies suggest that it may be mediated through body fat [22,23]. Cruz et al. [7] studied 101 prepubertal white and black children, and reported an association between IS and SBP and DBP after adjustment for lean and fat mass measured with dual energy X-ray absorptiometry. In contrast, Sinaiko et al. [22] did not find an independent association between IS, measured with the euglycemic insulin clamp, and BP in 357 white and black adolescents. Further, their observed association between fasting insulin and SBP disappeared after adjustment for BMI. These contrasting findings could stem from differences in study population, extent of adiposity and the method for IS measurement (hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp vs. IS estimates) or BP measurement (an average of two single measurements [7,22] vs. ambulatory BP monitoring [15,21]). Lurbe et al. [21] recently reported a higher morning SBP in the highest HOMA-IR tertile in a group of 87 overweight and obese children and adolescents. They suggested an added impact of obesity and insulin resistance on morning SBP, although in their study, consistent with our findings, the relationship between the surrogate estimates of IS (fasting insulin and HOMA) and morning SBP disappeared (p = 0.06) after adjustment for waist circumference, a correlate of VAT [24]. In the present study, consistent with the data of Sinaiko et al. [22], we show that in vivo IS, measured with the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp, is not related to SBP independent of adiposity in white overweight adolescents.

Several mechanisms could explain the relationship between adiposity and SBP including sodium retention, increased sympathetic nervous system activity, activation of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone and altered vascular function [25]. In our study, VAT was an independent predictor of SBP, in accordance with other studies that suggest that centrally located body fat is a more important determinant of BP elevation than peripheral body fat [26]. VAT is thought to play an important role in the expression of the metabolic complications of obesity due to its unique position with respect to portal circulation and its secretary function for various bioactive substances [27]. Consistent with our observation of VAT being an independent predictor of SBP, others have shown similar associations between VAT and BP in obese Korean [9] and white Canadian adolescents [10]. Furthermore, our present findings are in agreement with our previous observations of waist circumference being a determinant of the metabolic syndrome in childhood irrespective of the definition used [28,29].

Data with respect to the relationship between adiponectin and BP are limited and controversial. Several studies in adults have shown an independent contribution of adiponectin to BP [11,12,13]. In pediatrics, an independent inverse association between adiponectin levels and BP has been shown in obese adolescents [15] and in non-obese female adolescents [14]. On the other hand, other studies which included prepubertal children did not show this association in a school-based sample of French-Canadian children and adolescents [30] or in a multiethnic cohort of obese children and adolescents [31]. In our study, we found that adiponectin, independent of adiposity (BMI or %BF or VAT or SAT), has a significant inverse relationship with SBP.

Some studies in mice suggest that adiponectin is protective against hypertension through an endothelial-dependent mechanism [32]. Moreover, recently it was demonstrated in humans that adiponectin derived from perivascular adipose tissue regulates contractile vascular tone by increasing nitric oxide bioavailability, and this capacity is lost in obesity by the development of adipocyte hypertrophy, leading to hypoxia, inflammation, and oxidative stress [33]. Thus, the observed inverse relationship between adiponectin and SBP in our study could be a manifestation of a potential regulatory role of adiponectin on BP through one or more of these mechanisms.

The strength of our study is the methodology of assessing in vivo IS using the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp, considered the gold standard, and abdominal computed tomography for an accurate and direct measurement of VAT, a major culprit of obesity-related health risks. Further, we believe that the careful and standardized measurement of the BP in the present study, taken over an hour with the subjects in the supine position resting after careful acclimatization to the hospital setting, is another strength. However, others may view this differently that our BP values cannot be compared to other studies where BP was measured under different conditions.

The cross-sectional design, the relatively small sample size of the population and the lack of estimates of renal function (a determinant of BP) are limitations of our study. Also, as the present study was conducted in Caucasian subjects only, the relationships between BP, IS and adiponectin may differ in other ethnic groups.

In conclusion, our findings in overweight adolescents do not demonstrate a direct relationship between in vivo IS and BP, as proposed in the context of the metabolic syndrome, which implies that insulin resistance is the driving force for the metabolic syndrome components [34]. Rather, this relationship appears to be mediated through adiposity. A direct relationship between IS and BP could possibly exist in normal weight youths, but becomes overshadowed when obesity develops. The observed relationship between adiponectin and BP independent of adiposity and body fat distribution would suggest a potential modulatory role of adiponectin in BP regulation. The present observations should be pursued further to investigate if the relationships between BP, IS and adiponectin are similar in normal weight youths and/or weight reduction and decreases in visceral adiposity translate to improvement in BP independent of changes in adiponectin. Also, our and others’ findings provide a strong impetus for obesity intervention and prevention efforts to lessen the health burden of obesity-driven hypertension in pediatrics, and the future cardiovascular disease risk, the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in this millennium [35].

Disclosure Statement

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by United States Public Health Service grant RO1 HD27503 (SA), K24 HD01357 (SA), Richard L. Day Endowed Chair (SA), Department of Defense (SJL, FB & HT), ADA Career Development Award (SJL), MO1 RR00084 (GCRC) and UL1 RR024153 (CTSA). The sponsors had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data or in the writing of the report.

These studies would not have been possible without the nursing staff of the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center, the devotion of the research team (Nancy Guerra CRNP, Sabrina Kadri), and the laboratory expertise of Resa Stauffer, but most importantly, the commitment of the study participants and their parents.

References

- 1.Wang Y, Lobstein T. Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2006;1:11–25. doi: 10.1080/17477160600586747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniels SR. Complications of obesity in children and adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33(suppl 1):S60–S65. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owen CG, Whincup PH, Orfei L, Chou QA, Rudnicka AR, Wathern AK, Kaye SJ, Eriksson JG, Osmond C, Cook DG. Is body mass index before middle age related to coronary heart disease risk in later life? Evidence from observational studies. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33:866–877. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tirosh A, Shai I, Afek A, Dubnov-Raz G, Ayalon N, Gordon B, Derazne E, Tzur D, Shamis A, Vinker S, Rudich A. Adolescent BMI trajectory and risk of diabetes versus coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1315–1325. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorof J, Daniels S. Obesity hypertension in children: a problem of epidemic proportions. Hypertension. 2002;40:441–447. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000032940.33466.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reaven GM. Insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia: role in hypertension, dyslipidemia, and coronary heart disease. Am Heart J. 1991;121:1283–1288. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90434-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz ML, Huang TT, Johnson MS, Gower BA, Goran MI. Insulin sensitivity and blood pressure in black and white children. Hypertension. 2002;40:18–22. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000019972.37690.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman DS, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. The relation of overweight to cardiovascular risk factors among children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1175–1182. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim JA, Park HS. Association of abdominal fat distribution and cardiometabolic risk factors among obese Korean adolescents. Diabetes Metab. 2008;34:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Syme C, Abrahamowicz M, Leonard GT, Perron M, Richer L, Veillette S, Xiao Y, Gaudet D, Paus T, Pausova Z. Sex differences in blood pressure and its relationship to body composition and metabolism in adolescence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:818–825. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chow WS, Cheung BM, Tso AW, Xu A, Wat NM, Fong CH, Ong LH, Tam S, Tan KC, Janus ED, Lam TH, Lam KS. Hypoadiponectinemia as a predictor for the development of hypertension: a 5-year prospective study. Hypertension. 2007;49:1455–1461. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.086835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwashima Y, Katsuya T, Ishikawa K, Ouchi N, Ohishi M, Sugimoto K, Fu Y, Motone M, Yamamoto K, Matsuo A, Ohashi K, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Rakugi H, Matsuzawa Y, Ogihara T. Hypoadiponectinemia is an independent risk factor for hypertension. Hypertension. 2004;43:1318–1323. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000129281.03801.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kazumi T, Kawaguchi A, Sakai K, Hirano T, Yoshino G. Young men with high-normal blood pressure have lower serum adiponectin, smaller LDL size, and higher elevated heart rate than those with optimal blood pressure. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:971–976. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.6.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang KC, Chen CL, Chuang LM, Ho SR, Tai TY, Yang WS. Plasma adiponectin levels and blood pressures in nondiabetic adolescent females. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4130–4134. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shatat IF, Freeman KD, Vuguin PM, Dimartino-Nardi JR, Flynn JT. Relationship between adiponectin and ambulatory blood pressure in obese adolescents. Pediatr Res. 2009;65:691–695. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819ea776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arslanian SA, Lewy VD, Danadian K. Glucose intolerance in obese adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome: roles of insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction and risk of cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:66–71. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arslanian SA, Saad R, Lewy V, Danadian K, Janosky J. Hyperinsulinemia in African-American children: decreased insulin clearance and increased insulin secretion and its relationship to insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2002;51:3014–3019. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bacha F, Saad R, Gungor N, Arslanian SA. Adiponectin in youth: relationship to visceral adiposity, insulin sensitivity, and β-cell function. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:547–552. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinaiko AR, Gomez-Marin O, Prineas RJ. Relation of fasting insulin to blood pressure and lipids in adolescents and parents. Hypertension. 1997;30:1554–1559. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.6.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taittonen L, Uhari M, Nuutinen M, Turtinen J, Pokka T, Akerblom HK. Insulin and blood pressure among healthy children. Cardiovascular risk in young Finns. Am J Hypertens. 1996;9:194–199. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(95)00345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lurbe E, Torro I, Aguilar F, Alvarez J, Alcon J, Pascual JM, Redon J. Added impact of obesity and insulin resistance in nocturnal blood pressure elevation in children and adolescents. Hypertension. 2008;51:635–641. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.099234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinaiko AR, Steinberger J, Moran A, Prineas RJ, Jacobs DR., Jr Relation of insulin resistance to blood pressure in childhood. J Hypertens. 2002;20:509–517. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200203000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iughetti L, Bedogni G, Ferrari M, Pagliato E, Manzieri AM, De SM, Battistini N, Bernasconi S. Is fasting insulin associated with blood pressure in obese children? Ann Hum Biol. 2000;27:499–506. doi: 10.1080/030144600419323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S, Kuk JL, Hannon TS, Arslanian SA. Race and gender differences in the relationships between anthropometrics and abdominal fat in youth. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1066–1071. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotchen TA. Obesity-related hypertension: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical management. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:1170–1178. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanai H, Matsuzawa Y, Kotani K, Keno Y, Kobatake T, Nagai Y, Fujioka S, Tokunaga K, Tarui S. Close correlation of intra-abdominal fat accumulation to hypertension in obese women. Hypertension. 1990;16:484–490. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.16.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hutley L, Prins JB. Fat as an endocrine organ: relationship to the metabolic syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 2005;330:280–289. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200512000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Bacha F, Arslanian SA. Waist circumference, blood pressure, and lipid components of the metabolic syndrome. J Pediatr. 2006;149:809–816. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee S, Bacha F, Gungor N, Arslanian S. Comparison of different definitions of pediatric metabolic syndrome: relation to abdominal adiposity, insulin resistance, adiponectin, and inflammatory biomarkers. J Pediatr. 2008;152:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambert M, O’Loughlin J, Delvin EE, Levy E, Chiolero A, Paradis G. Association between insulin, leptin, adiponectin and blood pressure in youth. J Hypertens. 2009;27:1025–1032. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832935b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winer JC, Zern TL, Taksali SE, Dziura J, Cali AM, Wollschlager M, Seyal AA, Weiss R, Burgert TS, Caprio S. Adiponectin in childhood and adolescent obesity and its association with inflammatory markers and components of the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4415–4423. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ouchi N, Ohishi M, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Nakamura T, Nagaretani H, Kumada M, Ohashi K, Okamoto Y, Nishizawa H, Kishida K, Maeda N, Nagasawa A, Kobayashi H, Hiraoka H, Komai N, Kaibe M, Rakugi H, Ogihara T, Matsuzawa Y. Association of hypoadiponectinemia with impaired vasoreactivity. Hypertension. 2003;42:231–234. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000083488.67550.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenstein AS, Khavandi K, Withers SB, Sonoyama K, Clancy O, Jeziorska M, Laing I, Yates AP, Pemberton PW, Malik RA, Heagerty AM. Local inflammation and hypoxia abolish the protective anticontractile properties of perivascular fat in obese patients. Circulation. 2009;119:1661–1670. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.821181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrannini E. Is insulin resistance the cause of the metabolic syndrome? Ann Med. 2006;38:42–51. doi: 10.1080/07853890500415358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minino AM, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Tejada-Vera B. Death in the United States, 2007. NCHS Data Brief. 2009;1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]